Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Auditor General Criticizes Capital Health Accounting Practices

Uploaded by

Charles RusnellCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Auditor General Criticizes Capital Health Accounting Practices

Uploaded by

Charles RusnellCopyright:

Available Formats

Capital Health vows to clean up accounting: Auditor General's tongue-lashing over padded costs sparks change

Edmonton Journal Mon Jan 8 2007 Page: A10 / FRONT Section: Cityplus Byline: Charles Rusnell Dateline: EDMONTON Source: The Edmonton Journal

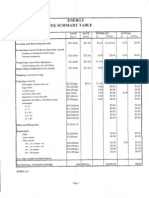

EDMONTON -- Auditor General Fred Dunn's sharp criticism of Capital Health's auditing practices has forced the health region to change the way it reports its finances to the public. In 2004 and 2005, Dunn privately told the health region to stop overstating its liabilities to hide the true state of its finances. Despite two warnings, Capital Health again overstated its liabilities in 2006 -- and by an even larger amount than in the previous two years. After the health region fixed $22 million in overstatements at the auditor general's request, its surplus jumped from $24 million to $46 million. Organizations sometimes overstate their future costs to reduce or eliminate surpluses in order to increase their chances of getting more -- or at least the same amount -- of money for their next year's budget. When Capital Health overstated its liabilities again in 2006, Dunn decided to get tough. He included a formal recommendation in his annual report, which would require the health minister to provide a written response to his complaint about Capital Health's questionable auditing practices. At his annual news conference in October, Dunn sharply criticized Capital Health. "Auditing should not be a hide-and-seek exercise whereby management hides the truth and auditors seek to get adjustments made in order that the financial statements reflect reality," Dunn said. After the news conference, Capital Health spokesman Steve Buick insisted the health region had not attempted to hide anything. He said if Capital Health's estimates were off, it was because the organization was pressed for time at the end of its fiscal year. "That is misleading," Dunn said in a recent interview. Capital Health, with a budget of more than $2.5 billion, is one of the region's largest corporations. Faced with questions about auditing practices, chief executive officer Sheila Weatherill repeatedly stated there was no intention to mislead the auditor general or the public. She repeatedly said Capital Health's failure to heed Dunn's warning for three consecutive years was due to a misunderstanding, and because she and her executives had not taken his advice seriously enough. She stressed Capital Health will comply in the future. But Dunn wondered how Capital Health could think he wasn't serious. He pointed out the health region's chief financial officer, Allaudin Merali, who is paid $487,000 a year, had previously worked for the office of the Alberta auditor general for 16 years.

Dunn also took issue with the region's decision to repay a $27-million debt in the same fiscal year it borrowed the money. The early repayment incurred an $880,000 penalty. Buick defended the decision after Dunn's October news conference. "With all respect to the (auditor general), we looked at the numbers on that debt repayment and thought it was good business for us," Buick said. Dunn rejected this explanation as "superficial and flawed." He said his auditors, led by assistant auditor general Jim Hug, spent a long time putting the auditing trail together. Most of the debt came from buying buildings on 107th Street in downtown Edmonton. "They (Capital Health) went through a great deal of angst over the financing," Dunn said. Capital Health explored its financial options before deciding to borrow from the government's Alberta Capital Finance Authority. "They should have known that I audit that too," Dunn said, in explaining how his auditors unravelled the complex trail. Capital Health borrowed $27 million in 2005 at a fixed 25-year rate of 4.95 per cent, a "very favourable rate," Dunn said. But the health region repaid the money within the same fiscal year, incurring the $880,000 penalty. "Why would anyone do this?" Dunn said. The answer, he said, is something accountants call window dressing. An accounting term, window dressing occurs when an organization "carries out artificial transactions that will later be reversed in order to improve temporarily the financial position shown by the financial statements, without disclosing that the financial position will later be reversed," according to the Dictionary of Accounting Terms. Dunn said someone in Capital Health's management made a conscious decision to employ these accounting practices. "Yes, because you have to record these things," he said. "You have to put them in your books and it takes time and effort to do it because the auditors are going to come in and look for some rationale, some documentation, to explain it, so you have to put a story together. "And of course then we go in and start banging away at the story to try determine what is incorrect," he said, adding that window dressing requires "a lot of time and effort and creativity." While Weatherill said there was no intent to mislead, Dunn disagreed. "Your question was, 'Was this done consciously?' and in my opinion, it was done with a conscious effort." Dunn said the auditing trail showed the decision to pay off the debt was made late in Capital Health's fiscal year. "It had to get done before March 31 in order to accomplish the impact, which is to reduce your cumulative surplus," Dunn said. Weatherill defended the decision to repay the debt early, saying it was based on the best available information.

Hug, who is responsible for auditing Capital Health, doesn't accept this explanation. "We used the word superficial, which would suggest it was not done to the level of diligence that you would expect from an organization of that size," Hug said. "Our expectation would have been a higher standard. It is a huge organization and they have got plenty of resources to do this kind of analysis." Dunn recommended that in the future, such debt repayment decisions should be vetted by the board that oversees Capital Health. That policy change has been made, Weatherill said. Despite the public drubbing of Capital Health's auditing practices by the auditor general, Weatherill said Capital Health and the office of the auditor general are on good terms. But twice during the interview, she mentioned the health region is not required to have the auditor general as its auditor. In fact, as Buick pointed out, three health regions in the province are not audited by the auditor general. The auditor general's office is aware that its criticism of Capital Health could lead to it being dropped as the organization's auditor. "It does put us in a difficult situation," Hug said. "We're trying to audit for the public and there are billions of dollars that go through the health system and in situations where we are brutally honest, we run the risk of perhaps not being reappointed. "Our objective is to get greater transparency into the health authorities. It has taken this kerfuffle, but I think it has finally driven home the message." crusnell@thejournal.canwest.com

You might also like

- Rebar Racism StoryDocument3 pagesRebar Racism StoryCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Overtime StingDocument6 pagesOvertime StingCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Kent V Martin RulingDocument64 pagesKent V Martin RulingCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Natives Were Drunk, Police Say: (Early Edition) : Rusnell, CharlesDocument3 pagesNatives Were Drunk, Police Say: (Early Edition) : Rusnell, CharlesCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Ms. T StoryDocument5 pagesMs. T StoryCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Judge Flays Engel For Legal TacticsDocument2 pagesJudge Flays Engel For Legal TacticsCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Infrastructure Political ExpediencyDocument3 pagesInfrastructure Political ExpediencyCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Mr. Wilkinson:: All Right. I Do Have A Statement ThatDocument8 pagesMr. Wilkinson:: All Right. I Do Have A Statement ThatCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Taxpayers Out $55M After Gov't Botches Ambulance Plan: (Final Edition)Document2 pagesTaxpayers Out $55M After Gov't Botches Ambulance Plan: (Final Edition)Charles RusnellNo ratings yet

- 2005 Govt Fleet InvestigationDocument17 pages2005 Govt Fleet InvestigationCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Mandel StoryDocument3 pagesMandel StoryCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Airbus Figure Loaned Money To Former AltaDocument2 pagesAirbus Figure Loaned Money To Former AltaCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- BC FOIP Release RulingDocument40 pagesBC FOIP Release RulingCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- 'Building Alberta' EmailDocument1 page'Building Alberta' EmailEmily MertzNo ratings yet

- Publc Affairs Bureau Politicization 5Document3 pagesPublc Affairs Bureau Politicization 5Charles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Public Affairs Bureau PoliticizationDocument5 pagesPublic Affairs Bureau PoliticizationCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Public Affairs Bureau Politicization 2Document5 pagesPublic Affairs Bureau Politicization 2Charles RusnellNo ratings yet

- FACT CHECK: Danielle Smith Wrong About Alberta Economic SummitDocument2 pagesFACT CHECK: Danielle Smith Wrong About Alberta Economic SummitAlberta Premier's Communications OfficeNo ratings yet

- Response To Defence - 004Document7 pagesResponse To Defence - 004Charles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Jumping Through HoopsDocument4 pagesJumping Through HoopsCharles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Oilsands Lawsuit 003Document5 pagesOilsands Lawsuit 003Charles RusnellNo ratings yet

- ATB Financial Pork Release - 004Document2 pagesATB Financial Pork Release - 004Charles RusnellNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Budgeting Case StudyDocument1 pageBudgeting Case Studykisschotu100% (1)

- Capital Budgeting Frameworks For The Multinational CorporationDocument12 pagesCapital Budgeting Frameworks For The Multinational Corporationsam gaikwadNo ratings yet

- For Ketto Waste Warriors Dharamshala Nov 2016Document32 pagesFor Ketto Waste Warriors Dharamshala Nov 2016Akshay BharadwajNo ratings yet

- Chapter One I.1 Background To The StudyDocument81 pagesChapter One I.1 Background To The StudyRathin BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Student QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesStudent Questionnaire'AcqhoziihFamousxzSzupfisxzticqkeiytEdNo ratings yet

- Life Skills Math Personal Budget Project: Marital Status/DependentsDocument11 pagesLife Skills Math Personal Budget Project: Marital Status/Dependentsapi-311634646No ratings yet

- Standard Costing: Incorporating Standards Into The Accounting RecordsDocument24 pagesStandard Costing: Incorporating Standards Into The Accounting RecordsLaurenz Simon Manalili100% (1)

- Assess The Economic Effects of A Significant Increase in Taxation On The UK EconomyDocument3 pagesAssess The Economic Effects of A Significant Increase in Taxation On The UK EconomyCalebP12No ratings yet

- 8 Ec413 Fiscal Policy 4Document49 pages8 Ec413 Fiscal Policy 46doitNo ratings yet

- Expansion Path: Key TermsDocument3 pagesExpansion Path: Key TermsBridgette Ace DeveineNo ratings yet

- Final BSNL BudgetDocument72 pagesFinal BSNL BudgetMohit Agarwal100% (1)

- Griffin Independent Budget Template 2014Document1 pageGriffin Independent Budget Template 2014Nicolás Carreño Castro100% (1)

- Budget Utilization Request and StatusDocument1 pageBudget Utilization Request and StatusGuiller C. MagsumbolNo ratings yet

- Kuratko 9 e CH 11Document40 pagesKuratko 9 e CH 11lobna_qassem7176No ratings yet

- Financial Planning and ForcastingDocument34 pagesFinancial Planning and ForcastingFarhan JagirdarNo ratings yet

- Pimentel vs. Aguirre Case DigestDocument2 pagesPimentel vs. Aguirre Case DigestArlene Q. Samante100% (1)

- INTRODUCTIONDocument41 pagesINTRODUCTIONSatyajeet SinghNo ratings yet

- Accounting Dr. Ashraf Lecture 01 PDFDocument7 pagesAccounting Dr. Ashraf Lecture 01 PDFMahmoud AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Fixed Cost: Marginal CostingDocument6 pagesFixed Cost: Marginal CostingJebby VargheseNo ratings yet

- The Budgeting Process and Budget Trends in The National Government of The PhilippinesDocument60 pagesThe Budgeting Process and Budget Trends in The National Government of The PhilippinestentenNo ratings yet

- Solution Q3 To Q5 TemplateDocument8 pagesSolution Q3 To Q5 TemplateTHANGAVEL PNo ratings yet

- 2019-2021 Mtef - FSP UpdatedDocument45 pages2019-2021 Mtef - FSP UpdatediranadeNo ratings yet

- Budget Defense PowerpointDocument17 pagesBudget Defense Powerpointapi-521538594No ratings yet

- Dasgupta Stresses On Employment Generation in Budget ProposalDocument6 pagesDasgupta Stresses On Employment Generation in Budget ProposalAnonymous NARB5tVnNo ratings yet

- NNPC - Monitoring Oil Production and Revenue GenerationDocument104 pagesNNPC - Monitoring Oil Production and Revenue Generationtsar_philip2010No ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Expansion of Maggi Noodles in NepalDocument2 pagesFactors Affecting The Expansion of Maggi Noodles in NepalDiwesh TamrakarNo ratings yet

- Economic Survey of Pakistan: Executive SummaryDocument12 pagesEconomic Survey of Pakistan: Executive SummaryBadr Bin BilalNo ratings yet

- Cost Accounting Book of 3rd Sem Mba at Bec DomsDocument148 pagesCost Accounting Book of 3rd Sem Mba at Bec DomsBabasab Patil (Karrisatte)100% (3)

- Advance P13-14Document10 pagesAdvance P13-14nadaNo ratings yet

- Case Study Income From BusinessDocument18 pagesCase Study Income From BusinessAhmad Taimoor RanjhaNo ratings yet