Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Redacted - USA Today Political Ad Buying in Denver

Uploaded by

Sunlight FoundationCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Redacted - USA Today Political Ad Buying in Denver

Uploaded by

Sunlight FoundationCopyright:

Available Formats

Targeting evident in one day of Denver political ads

ONE DAY'S WORTH OF POLITICAL ADS

What does nearly $700 million worth of political ads look like in a voter's living room? That's how much President Barack Obama and Mitt Romney and their supporters have spent so far on TV ads. In Denver, one of the hottest markets, one day of watching NBC affiliate KUSA means sitting through 93 presidential ads - 76 by the campaigns and 17 by outside groups.

KUSA TV Schedule Obama A: The Cheaters Obama B: Pay the Bills Obama C: Get Real Romney A: Stand Up to China Romney B: The Romney Plan

Source: USA TODAY research by Sara Dirkse of Ellis Edits. By Jerry Mosemak, Maureen Linke and Martha T. Moore, USA TODAY

If you were watching TV in Denver last week, you noticed a lot of political advertising. President Obama and former governor Mitt Romney have aired more than 26,000 ads in the swing state capital.

(Photo: Charles Dharapak, AP)

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

One Denver station aired 93 presidential ads Sept. 25 Campaigns target shows based on the voting habits of the audience Obama may be able to target better because he relies less on third-party ads

5:43AM EST October 2. 2012 Political campaigns know that what you watch says a lot about who you are likely to vote for. Democrats watch soap operas; Republicans watch news. College football skews Republican; the NBA skews Democratic -- except in Boston. Want to find independent voters? They're watching Biography.

As well-funded political campaigns seek every possible advantage, campaign ads are increasingly spread across the TV schedule based on the political skew of particular programs. Smaller audiences mean a TV show "is more likely to have a political personality,'' says Will Feltus of National Media, a Republican media-buying firm. "The Super Bowl doesn't skew Republican or Democratic, but the ColoradoColorado State (football) game almost certainly skews Republican.'' Ads are targeted not just to partisans but to partisans who vote, Feltus says: CBS' The Mentalist not only skews Republican, but 70% of them are likely voters. 60 Minutes viewers are more likely to be Democrats who vote. Undercover Boss viewers are disproportionately Republican, but vote less than average. Ditto Democrats and WWE Friday Night Smackdown. Last week in Denver host to Wednesday's first presidential debate President Obama's campaign aired four ads in one hour-long episode of The Doctors, a daytime chat show, and six ads during NBC's late-night lineup. Why? Because that's where the Democrats are: They're 28% more likely to watch daytime talk shows than all TV viewers, and 24% more likely to watch late-night chat, according to Scarborough Research, an audience research firm whose data are the basis of political media targeting.

President Obama calls supporters during a visit to a local campaign office Monday in Henderson, Nev. (Photo: Pablo Martinez Monsivais, AP)

Beginning with the George W. Bush campaign in 2004, campaigns have used data such as Scarborough's to target TV ads by audiences with considerable sophistication. As a result, ad buying becomes a combination of reaching big audiences which is why broadcast networks rather than cable channels get most of the ads and the right audiences. Denver, being the biggest media market in a key swing state, is seeing a deluge of ads. Audiences watching NBC affiliate KUSA last Tuesday saw 93 ads from Obama's and Mitt Romney's campaigns and two super PACs supporting them. KUSA and USA TODAY are owned by Gannett. The Obama campaign and the super PAC Priorities USA Action, ran more than twice as many ads as Romney and American Crossroads, 63 ads to 30 ads. Ads ran in every program from the early news at 4 a.m. to Last Call with Carson Daly at 1 a.m., More than 40% of the presidential ads ran during local news shows still a target for campaigns because they attract political independents who turn out to vote.

With targeting, "you can calculate the cost of (buying an ad in) the show not in terms of demographic rating points but in target voter ratings points,'' Feltus says. It's a lot of work, but worth it in a close race like this year's presidential election, he says. "All this stuff works at the margins. If it's a 1-point or 2-point race, it matters." In 2008, an analysis of media buys for Obama and his Republican rival, Sen. John McCain, showed that the Obama campaign reached a broader spectrum of independent and Republican leaning independents with its ad buying. Obama "was leaning more toward the (strategy) to reach out send a wide message, put some ads on programs where the demographics weren't necessarily favorable, they weren't all hard-core Democrats,'' says Travis Ridout, a Washington State University political scientist involved in the analysis. That included, for instance, religious programs, which have heavily Republican audiences. McCain was so hampered by lack of money that his campaign wasn't able to do a lot of program targeting, says Kyle Roberts of Smart Media Group, who was McCain's media buyer. This year, Obama, with the benefit of the experience of 2008, can do multiple layers of targeting with his TV buys: adults 25 and over, then women viewers, or even a third category. "They've mastered that system, strategically and tactically,'' Roberts says. Romney suffers from none of the financial constraints that McCain did. But it's not clear, media buyers say, that his campaign is running as nuanced a media buying program as Obama's. In Denver, for instance, Romney did not run ads during the Denver Broncos season opener on Sept. 9, the debut of the team's new marquee quarterback Peyton Manning. Obama ran three, at $28,000 each. On the Denver NBC affiliate last Tuesday, Romney ran 10 of 21 ads in local news and skipped prime time. (On other Denver stations, Romney has run ads during The Mentalist, NCIS, and NFL games.) Obama's media strategy may be more complex because a much larger proportion of proObama advertising is bought by his campaign, Roberts says. Romney is relying more on support from outside groups such as American Crossroads and another PAC called Restore Our Future. That means the Obama campaign is in charge of almost all the ad spending while Romney and his supporters by law cannot coordinate their efforts. "Obama money is all Obama money. Obama can do whatever he wants with it,'' Roberts says. Obama's money will also go further: Pro-Romney super PACs don't get the "lowest unit rate" that TV stations are required by the Federal Communications Commission to give candidates. In Denver, for instance, Romney paid $1,400 to run a 30-second ad during KUSA's 5 p.m. news. Crossroads had to pay $2,500. As a result, Romney's supporting groups "are going to find themselves spending an awful lot of money in the last three weeks to match Obama's spot count,'' says Jack Poor of the Television Bureau, the broadcaster's trade association.

And while TV stations are obligated to sell "reasonable amounts" of airtime to candidates close to the election, according to the FCC, there's no such duty to sell to superPACs; if a station wants to cap the amount of political ad time it sells in favor of regular advertisers like local auto dealers, it can. "There is only so much inventory they can buy,'' says Fletcher Whitwell, media director for R&R Partners, a political ad firm based in Las Vegas. That could mean targeting goes out the window, he says. "They may start being scientific but they may also just buy what's available.'' Contributing: Sara Dirkse in Denver.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- ReceptionDocument2 pagesReceptionSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- Information SessionDocument2 pagesInformation SessionSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- LuncheonDocument4 pagesLuncheonSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- FundraiserDocument2 pagesFundraiserSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- FundraiserDocument2 pagesFundraiserSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- FundraiserDocument1 pageFundraiserSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- LuncheonDocument2 pagesLuncheonSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- ReceptionDocument2 pagesReceptionSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- LuncheonDocument2 pagesLuncheonSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- ReceptionDocument2 pagesReceptionSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- FundraiserDocument2 pagesFundraiserSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- #PromoteOpenData: How Cities Can Use Social Media To Publicize Open Data PolicyDocument14 pages#PromoteOpenData: How Cities Can Use Social Media To Publicize Open Data PolicySunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Powerpoint - The Use of Animals in FightingDocument18 pagesPowerpoint - The Use of Animals in Fightingcyc5326No ratings yet

- Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission Regulations, 1954: (Corrected Up To 29.02.2020)Document93 pagesTamil Nadu Public Service Commission Regulations, 1954: (Corrected Up To 29.02.2020)DhivakaranNo ratings yet

- BDA Advises JAFCO On Sale of Isuzu Glass To Basic Capital ManagementDocument3 pagesBDA Advises JAFCO On Sale of Isuzu Glass To Basic Capital ManagementPR.comNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Indian Financial SystemDocument2 pagesEvolution of Indian Financial SystemvivekNo ratings yet

- Renato Nazzini The Law Applicable To The Arbitration Agreement Towards Transnational PrinciplesDocument22 pagesRenato Nazzini The Law Applicable To The Arbitration Agreement Towards Transnational PrinciplesJNNo ratings yet

- MCQ On Guidance Note CARODocument63 pagesMCQ On Guidance Note CAROUma Suryanarayanan100% (1)

- Scope of Inspection For Ammonia TankDocument3 pagesScope of Inspection For Ammonia TankHamid MansouriNo ratings yet

- Neelam Dadasaheb JudgementDocument10 pagesNeelam Dadasaheb JudgementRajaram Vamanrao KamatNo ratings yet

- REQUIREMENTS FOR Bfad Medical Device DistrutorDocument3 pagesREQUIREMENTS FOR Bfad Medical Device DistrutorEvanz Denielle A. OrbonNo ratings yet

- Economy of VeitnamDocument17 pagesEconomy of VeitnamPriyanshi LohaniNo ratings yet

- Important Notice For Passengers Travelling To and From IndiaDocument3 pagesImportant Notice For Passengers Travelling To and From IndiaGokul RajNo ratings yet

- Part IV Civil ProcedureDocument3 pagesPart IV Civil Procedurexeileen08No ratings yet

- The Last Hacker: He Called Himself Dark Dante. His Compulsion Led Him To Secret Files And, Eventually, The Bar of JusticeDocument16 pagesThe Last Hacker: He Called Himself Dark Dante. His Compulsion Led Him To Secret Files And, Eventually, The Bar of JusticeRomulo Rosario MarquezNo ratings yet

- Mongodb Use Case GuidanceDocument25 pagesMongodb Use Case Guidancecresnera01No ratings yet

- Application FormsDocument3 pagesApplication FormsSyed Mujtaba Ali BukhariNo ratings yet

- Vasquez Vs CADocument8 pagesVasquez Vs CABerNo ratings yet

- Global Payments NetworkDocument3 pagesGlobal Payments NetworkSadaqt ZainNo ratings yet

- Midf FormDocument3 pagesMidf FormRijal Abd ShukorNo ratings yet

- Credit Operations and Risk Management in Commercial BanksDocument4 pagesCredit Operations and Risk Management in Commercial Bankssn nNo ratings yet

- Sample of Notarial WillDocument3 pagesSample of Notarial WillJF Dan100% (1)

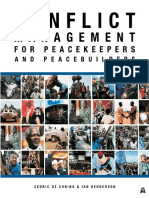

- Conflict Management HandbookDocument193 pagesConflict Management HandbookGuillermo FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Suraya Binti Hussin: Kota Kinabalu - T1 (BKI)Document2 pagesSuraya Binti Hussin: Kota Kinabalu - T1 (BKI)Sulaiman SyarifuddinNo ratings yet

- Sony SBS Flyer 03Document2 pagesSony SBS Flyer 03rehman0084No ratings yet

- Ise II Writing A Formal Letter OfaDocument1 pageIse II Writing A Formal Letter OfaCristina ParraNo ratings yet

- Lungi Dal Caro Bene by Giuseppe Sarti Sheet Music For Piano, Bass Voice (Piano-Voice)Document1 pageLungi Dal Caro Bene by Giuseppe Sarti Sheet Music For Piano, Bass Voice (Piano-Voice)Renée LapointeNo ratings yet

- The PassiveDocument12 pagesThe PassiveCliver Rusvel Cari SucasacaNo ratings yet

- Talend Data Quality DatasheetDocument2 pagesTalend Data Quality DatasheetAswinJamesNo ratings yet

- Is 14394 1996 PDFDocument10 pagesIs 14394 1996 PDFSantosh KumarNo ratings yet

- Erasmus Training Agreement and Quality CommitmentDocument5 pagesErasmus Training Agreement and Quality CommitmentSofia KatNo ratings yet

- Ralph Winterowd Interviews Jean Keating, December 12, 2023Document35 pagesRalph Winterowd Interviews Jean Keating, December 12, 2023eric schmidt100% (2)