Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stradivari Antonio Servais PDF

Uploaded by

Yla WmboOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stradivari Antonio Servais PDF

Uploaded by

Yla WmboCopyright:

Available Formats

32

ANTONIO STRADIVARI "SERVAIS" 1701

The renowned "Servais" cello by Stradivari is examined by Roger Hargrave Photographs: Stewart Pollens Research Assistance: Julie Reed Technical Assistance: Gary Sturm (Smithsonian Institute)

While attending one of M. Jansen's private concerts, I had the pleasure of meeting M. Servais of Hal, one of the most renowned violoncellists of the day . . . He was also rather eccentric and sometimes caused much mirth among the audience by mounting on a table 'cello and all, so that his part might be wellHoused curiously in a building known as the Museum of American History, is a magnificent, uncut, heard above the orchestra and further making most large pattern cello made by Antonio Stradivari in the comical faces which set the audience in a roar . . . The year 1701 and known as the "Servais". Like the "Hel- cello he played at the time I met him was a very large lier" inlaid violin, which I also measured and sized Strad, of the early period, and had never been recorded at this museum, the history of this cello is reduced in size as so many were, owing to the diffiwell documented. However until now no extensive culty men of medium size had in playing them, bemeasurements or drawings have ever been pub- cause Servais, being big and strong, found no difficulty with it. lished. This cello is known as the "Servais". Laurie goes on to discuss the use of a wooden rest The Hill brothers in their Life and Work of Stradior end pin by Servais's son who was also an accomvari say simply: plished cellist and eventually inherited the Strad The "Servais" violoncello, as far as we know, stands from his father. Although Servais senior is credited alone. It is not only the sole example of the year 1701 with having invented the endpin, Laurie states that but we believe it to be the only example which com- `M. Servais [junior], however, had been trained to use

In 184.6 an Englishman, James Smithson, gave the US Government $500,000 to be used `for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men.' This was the beginning of the vast institution which now dominates the downtown Washington skyline. It includes the J.F. Kennedy Centre for Performing Arts and the National Zoo, as well as many specialist museums, depicting the achievements of men in every conceivable field. From the Pony Express to the Skylab orbital space station, from Sandro Botticelli to Jackson Pollock this must surely be the largest museum and arts complex anywhere in the world. Looking around, one cannot help feeling that this is the sort of place where somebody might be disappointed not to find the odd Strad! And indeed, if you can manage to tear yourself away from the first video juke box (a recent acquisition) you will not be disappointed.

bines the grandeur of the pre1700 instrument with the more masculine build which we could wish to have met with in the work of the master's earlier years. Something of the cello's history is certainly worth repeating here, since, as is often the case, much of this is only to be found in rare or expensive publications. The following are extracts from the Reminiscences of a Fiddle Dealer by David Laurie, a Scottish violin dealer, who was a contemporary of J.B. Vuillaume:

33 street in Washington's Library of Congress. They seem to have experienced little difficulty in the playing of these two large cellos and have only praise for their magnificent sound qualities. Finally although we have very little information about Baroque cellos of the period, we do have Stradivari's drawings of the head and neck of the so-called "Violoncello da Venezia". This neck pattern was probably used in connection with the larger pattern of the "Servais" Until the later part of the 17th century players sel- cello. I have reproduced the drawing on the poster, dom used the register of the cello above the second in addition, I have included outlines of the bridges and third positions. As a result, neck and stop lengths which were probably used by Stradivari for this cello. were of little importance. Only when the potential of the cello was recognised as being something more At the Stradivari museum in Cremona, several inthan an instrument of bass accompaniment were teresting items can be viewed which, according to such matters as string and body lengths taken into Sacconi, were used in the construction of these consideration. As a direct consequence of this devel- "Venetian cellos", also referred to as bass cellos. They opment, many instruments of larger dimensions are as follows: were drastically and often catastrophically reduced in size. There is an interesting final paragraph to Laurie's Servais chapter: I may mention that the work of reducing these large Strads was a most serious and difficult one; the only maker who could do it really well was one named Menningand . . . Even Vuillaume admitted his superiority in this, and latterly advised any one who wished such a thing done to go to Menningand. i) A sheet of paper upon which is drawn a design for the correct positioning of the f-holes. A paper model of the head and neck (reproduced on poster). A sheet of paper with the geometric development of the scroll and pegbox drawn with a compass. (See p.935). Paper ,pattern of the side of the pegbox. Several bridge designs of different sizes in wood or paper. (See reproductions on poster). A facsimile of a bridge for the fixing of the neck elevation. the rest pin, as indeed nearly all artists outside England are.' This gives me the impression that the pin was probably in use before Servais senior's own need to lift the cello away from his rather large frame. In fact one might wonder how much of the extensive wear on the top left hand corner and the left hand edge of the Cbouts of the back were the result of the rather corpulent thighs of the Servais family.

ii) iii)

iv) Clearly such work was commonplace at this time and it seems likely that it is only thanks to the v) overlarge Servais family that this particular instrument remains unaltered. Though Stradivari himself was not solely responsible for the development of the violoncello, the greatest changes to this instrument's vi) design were taking place during his working lifetime: Needless to say, Stradivari made his own invaluable contributions, and he is justifiably credited with having perfected the proportions and dimensions which we now accept as standard. Of course changes did not In connection with this, the "Servais" itself has reentirely finish with Stradivari. Many features of the vealed some tantalizing secrets which will be discello, quite apart from the aforementioned endpin, cussed later. have been altered, but the basic pattern of the cello This cello is clearly the work of a man in the full like those of the violin and viola, has never been sucprime of fife. Neither talent nor resources have been cessfully improved since Stradivari's time. spared. It is a work which combines many of the best I have chosen to illustrate this particular cello for features of Stradivari's early and "golden" periods, several reasons: Firstly it is a thing of incredible having been made around the very point of change. beauty, and the extreme rarity of a large sized uncut It is not known if Stradivari made any other cellos beStradivari cello cannot be denied. Secondly in spite tween 1701 and 1707, when we see the first known of its large size it is often used for very challenging surviving example of his "forma B" which was evenrecitals. I have spoken with players of this, and of a tually to become the standard pattern of almost Strad of similar proportions, housed just across the every maker since. What we do know is that the "Ser-

34

vais" at the time of writing is the last of the master's larger models. The back of the cello is made up of two matching quartersawn wedges which have been carefully winged at the outside of both the top and bottom bouts. The wood is closely grown imported mountain maple. It has spectacular wild vibrating flames radiating downwards from the centre joint. This wide swirling figuration accentuates the grandeur of the form, an outline which might well have been created by Rubens. The edgework is clean and confident, and despite the previously mentioned wear to the top left hand comer, there is a symmetry and perfection which is only slightly illusory and which remains a constant feature of the whole instrument. Possibly because of the larger form, the edges seem unusually fine, although not at all weak. The purfling itself is narrow enough to have been used on a violin. Long,

elegant mitres finish it at the corners and several have been filled at the stings as is often the case with Stradivari's instruments. These mitres seem to point towards what must surely have been the inside angle of the corner's end before the instrument was worn. The purfling blacks are very intense and the poplar whites have the usual longitudinal hairline pores in them which is also typical of the classical Cremonese school in general. At the top and bottom of the back, the purfling is jointed by diagonal cuts across the centre joint. At the button the locating pin protrudes half way outside of the purfling only. At the bottom, it shows slightly on both sides. The purfling generally lies in the bottom of the channel but occasionally it appears to rise up the sides where the channel depth wavers slightly. The channel itself must have been quite deeply incised and in places it remains welldefined. The peak of the

35

Sketch of the inside of the belly of the "Servais" violoncello of 1701. On the original the following are visible: the drawing of the design of the f-holes with a pen, the step at the straight line of the lower wing; the arcs of the circle for the position and inclination of the notches; the hole made by the compass on the edge of the centre bout, the parallel lines for the height of the lower eye and for marking out the outline for the positioning of the f holes (from Sacconi's `Secrets of Stradivari").

edge, now at the halfway position between the out- growth with quite pronounced reed lines. The bass side and the purfling was originally almost certainly side has two waves running across the lower bouts closer to the outside edge. and over the left sound hole, which is not reflected on the right hand side. The belly arching, though In the upper and lower bouts the back arching does similar to the back, rises more suddenly under the not appear to be particularly full, rising as it does fingerboard and tailpiece. The long arch, not surrather gradually from the purfling channel. Only in prisingly, has sunk slightly at the bridge position. As the immediate corner areas is there some tendency may be seen from the arching templates, however, towards scooping. In contrast the central cross archthere has been some further distortion to the arching ing is very full. There is no evidence here of a weak particularly in the lower bouts. Although such disback arch, and despite the normal swelling of the tortions are always a possibility with a cello of this soundpost area there is little deformation. Perhaps width, in this case, the sinking may have been aggrabecause of the overall flatter quality of the arching, vated by the peculiar wave in the reed fines at this the ribs are exceptionally high. According to the Hill same point. I have made no attempt to correct the Brothers they are the highest ever to be recorded on arching templates, and prospective copyists should a Stradivari cello. The instrument is so well proporbear these problems in mind. The apparent flatness tioned, however, that the ribs simply do not appear to of the belly arch is, no doubt, like the back, accentube extraordinarily high. Unlike most cellos, the ribs ated by the overall width of the instrument and I feel of the "Servais" are in an excellent state of presersure that the widely spaced and somewhat upright vation. This may be due to the fact that they are set of the fholes have further added to this illusion. backed with a canvas or linen material between the already deep linings. Although we know that StradiAs would be expected, the sound holes are cleanly vari used linen to strengthen his ribs, I suspect that cut. The large top and bottom circles have been this lining material is not the original. The growth, neatly drilled at right angles to the plate. The circles cut and figure of the rib wood matches the back per- are joined by narrow flowing body sections which are fectly. In common with most of Stradivari's instru- also cut at right angles to the plate. The nicks are ments the slope of the flame runs in the same small and tidy. There is some shallow fluting to the direction all the way around the ribs. In this case lower wings which increases in depth as the wings from the belly edge it slopes slightly down towards widen and scoop down towards the purfling channel. the right. At the same time the flutes run up alongside the bodies of the holes producing a sharp outside edge and a The belly is made up of two wedges in the normal slight "eyebrow" effect over the top curve. Above the way. The two sides, however, do not match each other left hole this effect is optically increased by the preexactly, as is also the case with the "Gibson" viola, viously mentioned wave in the reed lines. There are (see THE STRAD, September 1986). It seems likely a small number of tool marks clearly visible in the that they are from the same tree but were not cut area of these flutings. This is, I believe, unusual for from the same wedge. Both pieces are of medium Stradivari at this period.

36 be shallower as was often the case (probably to facilitate easier carving). The head is cut exactly on the quarter and the workmanship throughout shows slightly more flair and boldness than is to be seen on earlier works. There is very little wear on the head and the wide chamfers still retain much of the original black lining. Unlike most violin heads of this and later periods, the turns on this scroll are not "oval" in appearance when viewed from the sides. The side view does however have a slightly angular flow described by the Hill Brothers as a "squarer aspect". The effect is very subtle and by no means reaches the extremes of Andrea Guarneri or his son Joseph. Generally when viewed from all sides the work of the head is well balanced. From the sides of the pegbox, for the first half turn of the scroll, the volutes remain fairly shallow, but they become increasingly deeper towards the eyes. The surface of the volutes remains relatively flat in cut with only a few faint tool marks visible on the final turns. A considerable amount of fairly thick varnish is retained in the volutes. The volutes on the left hand side of the head finish at the Although obviously more worn, the purfling, the eye with a sharp sting. Instead of a sting, on the right corners and edgework of the belly are in every way hand side, a tiny flat cut can be seen at the point of similar to the corresponding features on the back. entry into the eye. Since the Servais cello has not been opened for On the vertical surfaces of the eye and the second many years, I was not able to take measurement of turn are the usual traces of Stradivari's gouge, and the plate thicknesses, nor was I able to trace any re- here again a little extra varnish has settled and reliable figures. It is therefore important to note what mains intact. the Hill brothers had to say on the subject: Signs of the gouge or perhaps only the scraper are The interior construction [of the Servais] also also to be seen along the back of the pegbox and at shows that Stradivari sought to produce a different the chin in the fluting. Along the back of the pegbox tone result. He had hitherto considerably varied that the flutings are deep, with a flattening across the botall-important point, the thickness now making the tom of the curve in the normal way. At the chin the back and belly of stouter proportions, now thinner; flutings soften somewhat especially around the two but he appears to have at last decided that the in- protruding stings which continue the flow of the creased substance was more favourable for produc- chamfer mitres between the chin and the shoulders. ing a brighter, more strident tone. After careful As the flutings run over the top of the head they beexamination, and comparison with instruments of a come rounder in form and deeper under the front later date where they eventually blend gently into the throat It is interesting that in these observations, made at the start of the first turn. in 1888, there is no mention of a sunken belly arch. In Along the central spine between the flutings are view of what the Hill Brothers observed, I once again the usual pin holes where Stradivari placed his comrefer the reader to Sacconi's thicknessing diagrams. pass in order to mark out the widths of the head and The diagram referring to Stradivari's cellos is repro- pegbox (see reproduction of Stradivari's templates). duced on p.935. For further details of block sizes, lin- Slightly more unusual are the remains of the scribe ings and other inside work I must also refer the line upon which these compass points were set. The reader to Sacconi. pegbox, as with all of Stradivari's heads, is sensibly Although the flames are very slightly narrower deep and wide. The cello bears its original label, than those of the back and ribs, the head wood nev- dated 1701. ertheless matches well. The flame does not appear to It is always difficult to find an adequate means of As well as their obvious beauty, what makes these soundholes particularly interesting are the traces of Stradivari's layout work which remain. Clearly visible on the inside are the ink lines which defined the shape of the right hand soundhole body. There is also a deep step cut from the inside of the lower wing. On the inside of both holes there are compass arcs marking out the position of the nicks and the corresponding prick marks in the tips of the upper wings. Finally there are the remains of the parallel lines which were used to fix the position of the bottom circles. I have reproduced the diagram of the Servais cello sound hole, which illustrates these features, from Sacconi's book. Further explanation may also be found in the book. Before leaving the sound holes it is worth noting that at some time a bridge was placed behind the present position. This can clearly be seen on the photographs. Quite why this happened can only be guessed at, but the bridge must have remained there for some considerable time judging by the depth of the impressions.

37

Strip of paper bearing a compassdesigned the geometric development for the head and scroll from which were taken the measurements of the various widths of the back of the scroll and head

MEASUREMENTS (in nullimeters)

Thicknesses for the belly and back of the violincellos of Antonio Stradivari according to Sacconi

Back Length (over arch) 791,5 Upper bouts 363,5 Middle bouts 252 Lower bouts 467 Edge thickness Back Corners 6,5 Centre 5,5 Bouts 5,5 Overhang (back) Centre bouts 4,5 Top and bottom bouts 3.5/4 Rib heights Left Neck root 124,5 Upper corner 127,5 Lower corner 127,5 End pin 127,5 Purfling Distance from edge 5/5.5 Total width 1,5 Width of white 0,6 Stop length Left 427 Modern neck length 278

Belly 793 363 253 464 Belly 5,5 5 5,5

Right 125 127,5 127.75 127.25

Right 427 -

describing varnish. However, for what the description is worth, the cello has a rich covering of varnish, which is reddish brown in colour. In places the varnish is fairly thick and has a fine craquelure especially in the C-bouts and corners of the back and on much of the protected areas of the head. The ground, which is extremely clean where varnish is missing, changes from silver-grey, where the wear is extreme, to a golden-yellow, where only the varnish has disappeared. But even the most expensive photography and colour printing process cannot reproduce that

reflective sparkle of life, . which is the hallmark of a classical instrument. How are we to describe colours which change so dramatically in hue as the direction of the light shifts? What do such terms as texture and craquelure mean? There are certain characteristic crack formations for each type of ground and varnish film, which vary with age and with the methods and skills of the original maker. Some are microscopic, some are extremely coarse. Identifying the colour, texture,

38 craquelure, etc. of a specific maker is a matter of ex- at the home of the Prince, lured there first by the fine perience. Certainly photographs and words alone are collection of instruments... inadequate. Passing from the possession of Prince Chimay, the Many of the instruments which I have so far de- 'cello eventually came through Hill to Wurlitzer, a scribed in this series of articles, have been in private notable acquisition to America's treasury of great collections and access to them is naturally very lim- works. ited. This particular cello however, is on display durThe cello was donated to the Museum of American ing the normal museum opening hours. Since I can History by Miss Charlotte Bergen of Bernardville only ever paint a very limited picture of such works of art I might suggest that anyone wishing to know U.S.A., to whom lovers of music and musical instrumore about this particular cello can do no better than ments will be eternally grateful. to pay a visit to the National Museum of American History. The history of this cello is well summed up by the following quotations from E. boring's book How many Strads?: The "Servais" came into 'Vuillaume posession about 1845, after the death of M. Raoul,its previous owner, a Parisian who was well known as an amateur player. The famous cellist, Adrien Francois Servais (born at Hal, near Brussels, June 6, 1807; died there November 26, 1866) desired to possess the instrument but lacked the necessary means to acquire it. Owing to the friendship of the Russian Princess Youssoupoff (Yusupov) to whom Servais confided his ardent wish, the 'cello was ordered by her to be sent to (then) St. Petersburg, but before it arrived, the Princess died. However, her family arranged to purchase it and Servais became the owner... Servais used the 'cello throughout his life and at his death it passed to his son Joseph, who was also a fine performer; thus, two generations of celebrated players firmly established the name of Servais as the title of the instrument... After the death of Joseph Servais, the 'cello was sold to Auguste Couteaux about 1885, who purchased it for the use of his son Georges, a student. M. Couteaux is said to have paid 60,000 francs for the instrument, a considerable enhancement in its value, as, when Vuillaume owned the 'cello, his price was 12,000 francs. In 1893 the 'cello passed to William E. Hill & Sons, who sold it to Prince Caraman Chimay, an excellent player, friend of music and collector of rare instruments, who had been a friend and pupil of Joseph Servais. Prince Chimay became the victim of odious publicity when his wife, who was Clara Ward of Detroit, Michigan, eloped with the gypsy violinist, Jancsi Rigo (who died, it is said, of the bubonic plague in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1899), as the result of an acquaintance formed during frequent visits Rigo made

You might also like

- The 'Betts' Stradivari 1704: A MasterpieceDocument7 pagesThe 'Betts' Stradivari 1704: A MasterpieceParacelso CelsoNo ratings yet

- Pplleeaassee Ttaakkee Ttiim Mee Ttoo Rreeaadd Tthhiiss Wwaarrnniinngg!!Document8 pagesPplleeaassee Ttaakkee Ttiim Mee Ttoo Rreeaadd Tthhiiss Wwaarrnniinngg!!nhandutiNo ratings yet

- A History of the Violin Bow - A Selection of Classic Articles on the Origins and Development of the Bow (Violin Series)From EverandA History of the Violin Bow - A Selection of Classic Articles on the Origins and Development of the Bow (Violin Series)No ratings yet

- Antonio Stradivari 1694 'Maria Ex Muir Mackenzie': Description AND Measurements: Roger HargraveDocument7 pagesAntonio Stradivari 1694 'Maria Ex Muir Mackenzie': Description AND Measurements: Roger HargraveCarlos AlbertoNo ratings yet

- The History and Design of the Violin Bridge - A Selection of Classic Articles on the Development and Properties of the Violin Bridge (Violin Series)From EverandThe History and Design of the Violin Bridge - A Selection of Classic Articles on the Development and Properties of the Violin Bridge (Violin Series)No ratings yet

- Artikel 1986 09 Stradivari Gibson PDFDocument7 pagesArtikel 1986 09 Stradivari Gibson PDFFábio Daniel HadadNo ratings yet

- Artikel 1986 09 Stradivari Gibson PDF PDFDocument7 pagesArtikel 1986 09 Stradivari Gibson PDF PDFCarlos AlbertoNo ratings yet

- Technique and Interpretation in Violin-PlayingFrom EverandTechnique and Interpretation in Violin-PlayingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- 58042859Document8 pages58042859Weibin Liu100% (2)

- The Violin and Old Violin Makers: Being a Historical and Biographical Account of the Violin with Facsimiles of Labels of the Old MakersFrom EverandThe Violin and Old Violin Makers: Being a Historical and Biographical Account of the Violin with Facsimiles of Labels of the Old MakersNo ratings yet

- The Salabue StradivariDocument42 pagesThe Salabue Stradivarikoutetsu50% (2)

- Brothers AmatiDocument7 pagesBrothers AmatiPHilNam100% (1)

- Stradivari Instruments Ashmolean MuseumDocument8 pagesStradivari Instruments Ashmolean MuseumJose Osorio100% (2)

- Violins and Violin Makers Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the Violin.From EverandViolins and Violin Makers Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the Violin.No ratings yet

- Varnish PDFDocument4 pagesVarnish PDFpauNo ratings yet

- Making Transparent Golden Varnish from a Historical RecipeDocument3 pagesMaking Transparent Golden Varnish from a Historical Recipemarcellomorrone100% (1)

- Controlling Arch ShapeDocument9 pagesControlling Arch Shapenostromo1979100% (1)

- Creating a Scroll Using Geometric TemplatesDocument3 pagesCreating a Scroll Using Geometric TemplatesDeaferrantNo ratings yet

- Achieving Tonal Repeatability in Violins Through Plate Flexural StiffnessDocument9 pagesAchieving Tonal Repeatability in Violins Through Plate Flexural Stiffnessblancofrank545100% (1)

- Violin Construction PDFDocument43 pagesViolin Construction PDFNóra RajcsányiNo ratings yet

- Edge WorkDocument16 pagesEdge Worknostromo1979100% (1)

- Retuning the plates of a cello to improve toneDocument1 pageRetuning the plates of a cello to improve toneAnonymous K8QLiPNo ratings yet

- The Identification of Cremonese Violins Part 1Document8 pagesThe Identification of Cremonese Violins Part 1PHilNam100% (1)

- Working Methods Guarneri Del GesùDocument10 pagesWorking Methods Guarneri Del GesùhorozimbuNo ratings yet

- Cello DimensionDocument2 pagesCello DimensionChutchawan Ungern100% (1)

- Violin Tone and Violin Makers, by Hidalgo Moya (1916)Document302 pagesViolin Tone and Violin Makers, by Hidalgo Moya (1916)jruivo100% (2)

- Microsoft Word For The Strad Part 1 8 SeptDocument10 pagesMicrosoft Word For The Strad Part 1 8 Septnostromo1979100% (1)

- Recreating Classical Violin VarnishDocument15 pagesRecreating Classical Violin VarnishMassimiliano Giacalone100% (1)

- Gasparo Da SaloDocument31 pagesGasparo Da SaloFrancesco Maria MazzoliniNo ratings yet

- Christies String Instruments CatalogueDocument150 pagesChristies String Instruments Cataloguebeltedkingfisher100% (3)

- Hugh Reginald Haweis-Old Violins and Violin Lore. Famous Makers of Cremona and Brescia, and of England, France, and Germany (With Biographical Dictionary) - General Books LLC (2010)Document364 pagesHugh Reginald Haweis-Old Violins and Violin Lore. Famous Makers of Cremona and Brescia, and of England, France, and Germany (With Biographical Dictionary) - General Books LLC (2010)Maurizio Bisogno Lic Phil100% (1)

- Nicola Amati and The AlardDocument10 pagesNicola Amati and The AlardPHilNamNo ratings yet

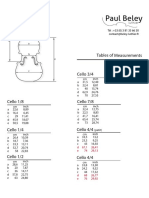

- Tables of Me Sure SP Be Ley CelloDocument1 pageTables of Me Sure SP Be Ley CelloPascal DupontNo ratings yet

- Luthier Familia BisiachDocument6 pagesLuthier Familia BisiachLobo EsteparioNo ratings yet

- Strad Tap TonesDocument5 pagesStrad Tap TonesAlfstrad100% (2)

- Martin Schleske explores empirical tools in violin makingDocument15 pagesMartin Schleske explores empirical tools in violin makingFábio Daniel HadadNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of Stradivari and Guarneri del GesùDocument5 pagesA Brief History of Stradivari and Guarneri del GesùKevinNo ratings yet

- Bow Rehair ProcessDocument2 pagesBow Rehair Processsalecello2113No ratings yet

- A Note On Practical Bridge Tuning For The Violin Maker Carleen M. HutchinsDocument4 pagesA Note On Practical Bridge Tuning For The Violin Maker Carleen M. HutchinsNikolai BuerginNo ratings yet

- 8 - Ways of HearingDocument5 pages8 - Ways of Hearingnostromo1979100% (1)

- Violin Templates and The Form PDFDocument9 pagesViolin Templates and The Form PDFAndrés Medina100% (1)

- K The Sound HolesDocument7 pagesK The Sound HolesTeggy GatiaNo ratings yet

- Coloring Agents For Varnish: Colors - General OverviewDocument1 pageColoring Agents For Varnish: Colors - General Overviewnostromo1979No ratings yet

- Area Tuning The ViolinDocument10 pagesArea Tuning The ViolinRotar Razvan100% (1)

- Refining Linseed OilDocument10 pagesRefining Linseed Oilnostromo1979No ratings yet

- 066-069 Trade SecretsDocument3 pages066-069 Trade Secretsblancofrank545100% (3)

- Two Violin Forms:: Commentary and AnalysesDocument17 pagesTwo Violin Forms:: Commentary and Analysesnostromo1979100% (1)

- Subject To ChangeDocument7 pagesSubject To Changenostromo1979100% (1)

- Facts About Violin Making - Tiegton - 1904Document29 pagesFacts About Violin Making - Tiegton - 1904Christopher WardNo ratings yet

- Violin Repair and RestorationDocument148 pagesViolin Repair and RestorationMichael Mayson100% (3)

- A Physicists Quest For The Secrets of StradivariDocument15 pagesA Physicists Quest For The Secrets of Stradivariyufencha15480% (2)

- The Great Violin Makers of CremonaDocument5 pagesThe Great Violin Makers of CremonaBrian Morales0% (1)

- Measuring and tuning a violin bridge's resonance frequencyDocument8 pagesMeasuring and tuning a violin bridge's resonance frequencyOmid Sharifi100% (1)

- Making The Violin Geometric Arching Shape - KopiaDocument24 pagesMaking The Violin Geometric Arching Shape - Kopianostromo1979100% (1)

- Plate Tuning PDFDocument132 pagesPlate Tuning PDFConsuelo FroehnerNo ratings yet

- Multiamp Firmware EvolutionDocument4 pagesMultiamp Firmware EvolutionJuanNo ratings yet

- LAS PLAYAS DE RIO (Guion) PDFDocument40 pagesLAS PLAYAS DE RIO (Guion) PDFAngel Ibañez BlesaNo ratings yet

- Tower InfoDocument2 pagesTower Infoparasara66No ratings yet

- 20 - 01-01 Q MagazineDocument132 pages20 - 01-01 Q MagazineM BNo ratings yet

- Appreciating Contemporary ArtsDocument14 pagesAppreciating Contemporary ArtsluckykunoNo ratings yet

- GSM Mobile CommunicationsDocument81 pagesGSM Mobile CommunicationsPalash Sarkar100% (1)

- Filipino artists and awardeesDocument1 pageFilipino artists and awardeesLiza Joy A. RamirezNo ratings yet

- Poems For Practice AnnotationDocument6 pagesPoems For Practice AnnotationxxpolxxNo ratings yet

- A Master and Slave Control Strategy For Parallel Operation of Three-Phase UPS Systems With Different Ratings48Document7 pagesA Master and Slave Control Strategy For Parallel Operation of Three-Phase UPS Systems With Different Ratings48Mohamed BerririNo ratings yet

- Perusal Script: Chip Deffaa Irving Berlin Chip DeffaaDocument77 pagesPerusal Script: Chip Deffaa Irving Berlin Chip DeffaaJoeHodgesNo ratings yet

- Ecce Screening Test PDFDocument40 pagesEcce Screening Test PDFJohn Spiropoulos0% (1)

- Watchmen Episode 9Document44 pagesWatchmen Episode 9Chauncey OfThe HerosJourneyNo ratings yet

- Vixen by Jillian LarkinDocument19 pagesVixen by Jillian LarkinRandom House Teens0% (1)

- Rap Rap: Rapping (Mcing) and Djing (Audio Mixing and Rapping (Mcing) and Djing (Audio Mixing andDocument3 pagesRap Rap: Rapping (Mcing) and Djing (Audio Mixing and Rapping (Mcing) and Djing (Audio Mixing andemodel8303No ratings yet

- Fate Index Sorted by Subject Then Year Then MonthDocument794 pagesFate Index Sorted by Subject Then Year Then MonthDharmaMaya Chandrahas100% (1)

- Airtel Zambia IR.21 Report June 2016Document14 pagesAirtel Zambia IR.21 Report June 2016intorefNo ratings yet

- Alone in The Dark The New Nightmare Prima Official EguideDocument144 pagesAlone in The Dark The New Nightmare Prima Official EguideFernando PinheiroNo ratings yet

- An-593 Broadband Linear Power Amplifiers Using Push-Pull TransistorsDocument13 pagesAn-593 Broadband Linear Power Amplifiers Using Push-Pull TransistorsEdward YanezNo ratings yet

- Gumshoe 1st 10 PagesDocument11 pagesGumshoe 1st 10 PagesPat DowningNo ratings yet

- TM11-2654 Vacuum Tube Voltmeter Hickok Model 110-B, 1945Document89 pagesTM11-2654 Vacuum Tube Voltmeter Hickok Model 110-B, 1945david_graves_okstateNo ratings yet

- Principal I&C Engineer or Principal Instrumentation and ControlDocument3 pagesPrincipal I&C Engineer or Principal Instrumentation and Controlapi-78419400100% (1)

- Globecom 2014 WS On 5G New Air Interface NTT DOCOMODocument31 pagesGlobecom 2014 WS On 5G New Air Interface NTT DOCOMOsubapacetNo ratings yet

- YAMAHA YAS-62 ManualDocument12 pagesYAMAHA YAS-62 ManualTimikiti JaronitiNo ratings yet

- Jeep WJ 2004 Grand Cherokee MOPAR Parts CatalogDocument432 pagesJeep WJ 2004 Grand Cherokee MOPAR Parts CatalogravenpisuergaNo ratings yet

- Cyrille Aimée & The Surreal Band - A Dream Is A Wish (In Eb)Document4 pagesCyrille Aimée & The Surreal Band - A Dream Is A Wish (In Eb)zeuta1No ratings yet

- 01 Amor Prohibido - GuitarDocument1 page01 Amor Prohibido - Guitarturismodeautor637No ratings yet

- B.ed. Thesis. Language Learning Through Music. Drífa SigurðardóttirDocument33 pagesB.ed. Thesis. Language Learning Through Music. Drífa SigurðardóttirKarthik Karthi100% (1)

- Ryanair Magazine January-February 2012Document154 pagesRyanair Magazine January-February 2012Sampaio RodriguesNo ratings yet

- ZTE - GSM - WCDMA Cell Reselection & CS HandoverDocument112 pagesZTE - GSM - WCDMA Cell Reselection & CS HandoverMuhammad Haris100% (1)

- Avengers Theme-Cello 2Document2 pagesAvengers Theme-Cello 2renatocomeairisNo ratings yet