Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Algorithm For HPP

Uploaded by

Fransiscus RonaldoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Algorithm For HPP

Uploaded by

Fransiscus RonaldoCopyright:

Available Formats

OBSTETRICS

Management Algorithm for Atonic Postpartum Haemorrhage

Edwin Chandraharan, MBBS, MS(Obs&Gyn), DFFP(UK), MRCOG; Sabaratnam Arulkumaran, MBBS, MD, PhD, FRCOG

t is estimated that every year, about 600,000 to 800,000 women die during childbirth around the world. In the developing world, postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) accounts for up to half of all maternal deaths. Even in developed countries, life-threatening PPH occurs in about 1 in

1,000 deliveries. The latest Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the UK has listed PPH as the third most common direct cause of maternal mortality.1 And we should not forget that many women survive with severe morbidity. Apart from anaemia, fatigue, depression and the risks of blood transfusion in the short term, many women require a hysterectomy to save their lives. This results in the loss of fertility in the prime of their lives, leading to social and psychological consequences. It is also well known that severe PPH can cause necrosis of the anterior pituitary gland, leading to Sheehans syndrome. Three delays have been identified as the causes of maternal death: delay in seeking medical care, delay in reaching healthcare facilities and delay in receiving appropriate care in a healthcare institution. The former two are seen mainly in developing countries. The latter, however, is common to both developing and developed countries. The Confidential Enquiries has in fact emphasized that deaths caused by PPH are due to too little done too late.1 In this article we present an algorithm to manage atonic PPH, a condition that contributes

to significant maternal morbidity and mortality in both the developing and developed world. The algorithm incorporates measures aimed at timely and appropriate management of atonic PPH to save lives and to avoid serious morbidity.

DEFINITION

PPH refers to the loss of more than 500 mL of blood from the genital tract after delivery. A volume of 500 mL is an arbitrary cutoff volume. In an anaemic patient, even less blood loss may cause morbidity and mortality. During caesarean sections, many obstetricians would consider blood loss of 1,000 mL as a cutoff point. This provides an allowance for more bleeding that occurs during a caesarean section as compared with vaginal delivery. Blood loss is often underestimated by healthcare professionals. It has been estimated that PPH occurs in 2% to 11% of deliveries; if an

JPOG MAY/JUN 2005 106

OBSTETRICS

objective assessment of blood loss is made, the incidence may rise up to 20%. A practical definition of PPH would be any bleeding from the genital tract that results in haemodynamic instability, which may endanger the life of the mother. PPH that occurs within the first 24 hours of delivery is called primary PPH. Common causes are atonic uterus, trauma to the genital tract, presence of retained placenta and membranes, and coagulopathy. An atonic uterus is the commonest cause of primary PPH, accounting for 80% of all cases.2 Bleeding that occurs after 24 hours is called secondary PPH, and is commonly due to retained tissue and/or infection. In this article, we focus our discussion on the management of primary PPH caused by uterine atony.

namic instability. It is always better to overestimate the blood loss and be proactive. Level of consciousness, pulse, blood pressure and, if facilities are available, oxygen saturation should be monitored. At the time of the insertion of two large-bore (14G) IV cannulae, blood should be taken for investigations. These include full blood count (FBC), clotting profile, urea and electrolytes, and grouping and crossmatching. Rapid fluid infusion with crystalloids and colloids should be carried out until crossmatched blood is available. Crystalloids (0.9% normal saline or

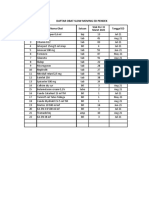

Figure 1. Management algorithm for of atonic PPH HAEMOSTASIS.

H A Ask for help Assess (vital parameters, blood loss) and resuscitate Establish aetiology, ensure availability of blood, ecbolics (syntometrine, ergometrine, bolus Syntocinon) Massage uterus Oxytocin infusion/prostaglandins IV/per rectal/IM/intramyometrial Shift to theatre exclude retained products and trauma/bimanual compression Tamponade balloon/uterine packing Apply compression sutures B-Lynch/modified Systematic pelvic devascularization uterine/ovarian/quadruple/internal iliac Interventional radiologist if appropriate, uterine artery embolization Subtotal/total abdominal hysterectomy

M O

T A

MANAGEMENT OF ATONIC PPH

PPH is an obstetric emergency. Overtreatment causes less harm than inaction. Accurate estimation of blood loss, appropriate replacement of volume and coagulation factors and a multidisciplinary approach are essential. Management should follow a clear and logical sequence of steps. We have attempted to formulate a management algorithm for this serious and potentially fatal condition. (Figure 1) The mnemonic HAEMOSTASIS spells out the suggested actions that may facilitate the management of atonic PPH in a logical and stepwise manner.

Hartmanns solution) are preferred over colloids, as the latter are associated with a 4% increase in the absolute risk of maternal mortality compared with crystalloids.3 The maximum recommended dosage of colloids is 1,500 mL in 24 hours.

Establish Aetiology, Ensure Availability of Blood and Ecbolics

Establish Aetiology

Ask for HELP It is prudent to ask for help. The presence and advice of a senior obstetrician, midwife, anaesthetist and haematologist are vital. Services of ancillary staff should be sought to help in the management. A multidisciplinary approach would optimize the monitoring and management of fluids, electrolytes and coagulation parameters as well as provide input if further measures are necessary. Assess and Resuscitate It is important to make an initial assessment regarding the degree of blood loss and the severity of the haemody-

It is vital to try to identify a cause while resuscitation is being carried out to save valuable time. For the purpose of this article we confine our discussion to atonic PPH. The uterus should be examined for contraction and retraction; it may also be worthwhile to check for free fluid in the abdomen, if the history suggests trauma (previous caesarean section, difficult instrumental delivery) or if the patients condition is poor compared with what is expected based on the estimated blood loss. It is important to ask about the completeness of the placenta and membranes. If there is doubt, the patient should be prepared for examination under anaesthesia. It is important to

JPOG MAY/JUN 2005 107

OBSTETRICS

exclude any trauma to the genital tract. During caesarean section, the uterine cavity may be explored to remove remnants of placenta and membranes, if present. A morbidly adherent placenta may pose a problem during both vaginal delivery and caesarean section. Aggressive, appropriate and timely management is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality. If difficulty is experienced during the removal of the placenta or if the placenta is deemed incomplete, the uterine cavity should be explored to exclude retained products. Following vaginal delivery, a uterine tamponade can be attempted prior to laparotomy to arrest haemorrhage in cases of placenta accreta. If haemorrhage due to a morbidly adherent placenta occurs during a caesarean section, haemostatic sutures, systemic pelvic devascularization and uterine artery embolization may be tried. A placenta increta or percreta may be encountered during caesarean section, especially in the presence of a previous uterine scar.

Ecbolics

not be acceptable to some patients. Hence, anaesthetists and haematologists should be involved very early to ensure optimum fluid management. In the case of massive PPH, where more than 30% of blood volume is lost, blood transfusion should be considered very early, especially in the presence of continued bleeding. Until crossmatched blood is available, O negative or uncrossedmatched group-specific blood may be transfused if there were no abnormal antibodies in the recipients blood.

Massage the Uterus It is important to massage the uterus to stimulate uterine contraction and retraction and this should be commenced very early. It may act synergistically with the uterotonic drugs. Oxytocin Infusion/Prostaglandins Syntocinon 40 units can be added to 500 mL of normal saline and infused at a rate of 125 mL/hour. It is important to avoid fluid overload, as fatal pulmonary and cerebral oedema with convulsions due to dilutional hyponatraemia has been reported. This is caused by the antidiuretic hormone (ADH)-like effect of oxytocin. Hence, careful monitoring of fluid input and output is essential if oxytocin is infused in large amounts. Prostaglandins are invaluable in the management of atonic PPH, although they are not recommended as prophylaxis of PPH due to their adverse gastrointestinal side effects. Hemabate (15-methyl prostaglandin 2 alpha) 250 g can be administered intramuscularly. The dose can be repeated every 15 minutes for a maximum of eight doses (2 mg).5 However, it is advisable to move the patient to the theatre if profuse bleeding persists after three doses of Hemabate. Intramyometrial injection of Hemabate has been tried,6,7 but recent studies have questioned its effectiveness. One should be aware that serious complications, including severe hypotension and cardiac arrest, have been reported with systemic prostaglandin administration. If the PPH is unresponsive to ergometrine or oxytocin, rectal misoprostol (8001,000 g) may be

Once atonic uterus has been identified as the cause of PPH, measures should be taken to ensure uterine contraction and retraction. Syntometrine (or, if not available, ergometrine) can be repeated. Syntocinon (10 units) can be administered as a slow IV bolus.

Ensure Availability of Blood and

Blood Products

Replacement of the circulating blood volume with crystalloids and colloids should be followed by restoration of the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and correction of any derangements in coagulation. This involves transfusion of blood and blood products. In special circumstances, autotransfusion may be considered, although during a caesarean section this carries a theoretical risk of amniotic fluid embolism and infection. Autotransfusion involves collection of maternal blood and the use of a cell-saver device to wash and filter the blood to remove the leukocytes and reinfuse the red cells.4 However, autotransfusion and other blood products may

JPOG MAY/JUN 2005 108

OBSTETRICS

tried.8,9 This is a valuable option in developing countries due to its low cost and relatively easier storage. Apart from IV crystalloids, colloids, blood and oxytocin, infusion of blood products needs to be considered. In massive obstetric blood loss, rapid infusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) may be required to replace clotting factors other than platelets. It is recommended that with every 6 units of blood transfusion, 1 L of FFP should be administered (15 mL/Kg). Hence, four to five bags of FFP are required, as each bag contains about 200 to 250 mL of FFP. It is important to maintain the platelet count above 50,000 by infusing platelet concentrates when indicated. Cryoprecipitate may also be needed if the patient develops disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and her fibrinogen drops to less than 1 g/dL (10 g/L).

hospital switchboard (e.g. Code Blue). A tamponade test, which has a positive predictive value of 87% for the successful management of PPH, using a Sengstaken tube was described.10 If the tamponade arrests the bleeding (i.e. positive), the chances of the patient requiring any further surgical intervention is remote. However, if this fails to control the haemorrhage, the patient needs a surgical intervention. Uterine tamponade with a balloon is easy to insert and takes only a few minutes. It arrests the bleeding and may prevent coagulopathy due to massive blood loss and the need for further surgical procedures. It should be considered in all patients not responding to medical therapy. Although a Sengstaken-Blakemore oesophageal catheter (SBOC) is most commonly used, the Rusch urological hydrostatic balloon11 and the Bakri SOS balloon12 may also be used. Usually a volume of about 300 to 400 mL may be required to exert the desired counter pressure to stop bleeding from the uterine sinuses. In developing countries, if these catheters are not freely available, uterine packing could be tried with sterile gauze. A tamponade in time is likely to reduce the need for blood transfusion, laparotomy and hysterectomy and thus may help preserve fertility. Figure 2 shows a tamponade balloon with a pressure-reading device that helps to infuse the volume needed to achieve a pressure close to the systolic pressure to stop the bleeding. These special devices are currently undergoing clinical trials after the success with SBOC balloons.

Shift to Theatre If the patient continues to bleed despite initial management, it is best to transfer her to the theatre. Examination should be carried out to exclude any retained placental tissue or membranes. If retained products are suspected, manual removal and uterine curettage should be carried out. A bimanual compression can be carried out at this stage to squeeze the uterus between the abdominal and vaginal hands. Tamponade or Uterine Packing In the presence of intractable PPH despite initial management, it is important to consider the onset of coagulopathy being superimposed on refractory atony. The use of uterine tamponade may help in arresting haemorrhage. It also allows adequate time to correct the coagulopathy if present. It is advisable to involve senior members of the obstetric team at this point, if this has not been done earlier. Involvement of a haematologist is mandatory and the intensive care unit should be alerted. Special protocols should be in place for the management of massive obstetric haemorrhage. The first step should be to alert all members of the team (including the haematologist and the hospital porter) in case of an emergency through the

Apply Compression Sutures Failure of the tamponade test to arrest haemorrhage warrants laparotomy. The decision to perform a laparotomy must be made early in these circumstances. Consent for examination under anaesthesia, tamponade, laparotomy and hysterectomy should have been obtained as the patient is being moved to the theatre. This may not always be feasible due to the patients condition or her level of consciousness. In such cases, it may be advisable to inform her next-of-kin of the possibility of laparotomy

JPOG MAY/JUN 2005 109

OBSTETRICS

and its sequelae. Laparotomy allows for direct visualization and access to the uterus as well as to the pelvic vasculature. Direct uterine massaging may be tried. It is very important Figure 2. Tamponade balloon with a pressure reading device.

Bedside pressure-reading device (reads 102 mm Hg) Drainage channel

compression force.14 This technique also alleviates the need for opening the uterus. Horizontal full thickness compression sutures have also been tried, especially to control bleeding from the placental site in placenta praevia at the time of caesarean section.15 These could also be applied in the lower segment, while taking care not to obliterate the cervical canal. (Figure 3A) The risk of damage to the bladder can be prevented by ensuring the bladder reflection is below the level of suture insertion. Passage of sutures 2 cm medial to the lateral border of the uterus is aimed at preventing ureteric injuries. A combination of multiple vertical compression sutures may be needed in some cases. (Figure 3B) Cho et al16 described a multiple square suturing technique, which approximates anterior and posterior uterine walls at various points, virtually obliterating the uterine cavity. These vertical compression and multiple square sutures are easy to perform, less time-consuming and can be applied by less experienced surgeons as they are well within the uterine body and do not involve areas traversed by uterine vessels or ureters.

to strike the right balance between the need to save life and the desire to preserve the patients fertility. Before trying any conservative surgical procedures, it is essential to reassess the situation based on the amount of blood loss, persistence of bleeding, haemodynamic status and the

Tamponade balloon with 350 mL of saline

3-way tap to fill the balloon and to take pressure readings

patients parity. It is prudent to discuss with the anaesthetist regarding her ability to withstand possible further bleeding if conservative measures fail. This is especially true in developing countries, where the patient might have lost a significant amount of blood by the time she reaches the referral centre, which might have limited amount of blood for transfusion. In such situations, it is wiser to consider radical measures, which include total or subtotal hysterectomy to save the patients life albeit at the cost of her fertility. On the other hand, if the patients condition is stable, compression sutures can be tried. Compression sutures were first described by Christopher B-Lynch and hence they are often called the B-Lynch sutures.13 Bimanual compression can be applied to the uterus to determine whether a compression suture is likely to be of value. The anterior and posterior walls are apposed by vertical brace sutures using a delayed absorbable suture material, resulting in continuous compression of the uterus. Various modifications have been made to this original technique. These include using two separate vertical compression sutures instead of one to increase the tension applied and hence the

JPOG MAY/JUN 2005 110

Systematic Pelvic Devascularization If the compression sutures fail, ligation of blood vessels supplying the uterus should be tried. These include ligation of both uterine arteries, followed by tubal branches of both ovarian arteries proximal to the ovarian ligament (called the quadruple ligation). Uterine artery ligation is straightforward once the uterovesical fold of peritoneum is incised and the bladder is reflected down.17 A window is made in the broad ligament just lateral to the uterine vessels and the needle is passed through this opening. Medially, the needle is passed through the lower uterine myometrium, about 2 cm from the lateral margin, thus getting a good bite and then tie. The same procedure is repeated on the other side. If bleeding continues, tubal branches of both ovarian arteries can be tied medial to the ovarian ligament. The needle should be passed through a clear area of the mesosalpinx on either side of the blood vessels.

OBSTETRICS

Internal iliac artery ligation is an option if bleeding persists. This requires an experienced surgeon who is familiar with the anatomy of the lateral pelvic wall. Routine identification of the internal iliac vessels and the ureters during elective hysterectomies may help obstetricians to build up confidence when faced with an emergency. The parietal peritoneum may be picked up divided at the lateral pelvic wall at the level of the pelvic brim after identifying the ureter as it crosses the common iliac vessels. It may be then reflected medially along with the medial leaf of the broad ligament and the ureter be held away from the internal iliac vessels by a loop. The internal iliac artery should then be traced from above downwards until it divides into the anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior division should be ligated with black silk or linen (permanent suture material). The procedure should be repeated on the other side. Alternatively, the broad ligament may be opened by clamping, cutting and ligating the round ligaments and the lateral pelvic wall approached through this route. Some obstetricians prefer this route as they are familiar with the same procedure during routine hysterectomy. Bilateral internal iliac artery ligation has been found to reduce the pulse pressure by up to 85% in arteries distal to the ligation. This translates to an acute reduction in the blood flow by about 50% in the distal vessels.18 The reported success rate of this procedure has been between 40% and 75%19 and is invaluable for avoiding a hysterectomy. Potential complications include haematoma formation in the lateral pelvic wall, injury to the ureters, laceration of the iliac vein and accidental ligation of the external iliac artery. Ligation of the main trunk of the internal iliac artery may result in intermittent claudication of the gluteal muscles due to ischaemia. Fortunately, these complications are rare. Examining the femoral pulse prior to tightening the ligature, proper identification of anatomical structures and ligating the anterior division of the internal iliac artery may help to prevent these complications.

Interventional Radiologist Figure 3. B-Lynch sutures. In women who are not acutely A compromised or bleeding severely, interventional radiology can be Vertical compression considered. This procedure is usually sutures performed under fluoroscopic guidance by an interventional radiologist. The target vessel (internal iliac, uterine or ovarian) is reached by passing a Uterus catheter via the femoral artery. Various materials are used to occlude the vesHorizontal sels. These include gelatin sponge, sutures after reflecting polyurethane foam or polyvinyl alcohol the bladder particles, and are usually resorbed down 20 within 10 days. The success rates may B be as high as 85% to 95% and the Multiple vertical compression sutures entire procedure may take about 1 hour.21,22 Uterine artery embolization helps to avoid radical procedures and preserve fertility. Menstruation typically returns within 3 months and subsequent pregnancies have been reported.23 This technique is also useful in the presence of coagulopathy. In cases where PPH is anticipated (presence of placenta accreta or increta), (A) Technique of separate vertical and embolization catheters can be placed horizontal compression sutures; (B) multiple vertical compression sutures. prophylactically prior to a planned caesarean section, as this may help appropriate management without compromising future fertility. Complications include vessel perforation, haematoma, infection and tissue necrosis.24 Uterine necrosis has also been reported and hence the need to inform the patient regarding this uncommon complication. This procedure should be carried out by radiologists with expertise in interventional radiology. Subtotal or Total Abdominal Hysterectomy Hysterectomy should be total or subtotal depending on

JPOG MAY/JUN 2005 111

OBSTETRICS

the clinical situation. If the bleeding is predominantly from the lower segment (as in PPH following a major degree placenta praevia), a total abdominal hysterectomy is warranted. A subtotal hysterectomy may be performed if the bleeding is mainly from the upper segment and the cause is unresponsive uterine atony. Subtotal hysterectomy has lower morbidity and mortality rates and requires less time to perform. Hysterectomy is the last resort in the management of atonic PPH. However, one may have to resort to hysterectomy much earlier if the haemodynamic condition is unstable and if there is uncontrollable bleeding despite other medical and surgical measures. Due to the anatomical changes of pregnancy, it is important to exercise utmost care to prevent visceral trauma, especially of the bladder and ureters. It is also important to clamp the ovarian ligament medially to avoid non-intentional or inadvertent oophorectomy. The 15-year experience of obstetric hysterectomy from a tertiary centre in Nigeria revealed a maternal mortality rate of 12.5% and urinary tract injury rate of 7.5% after this procedure.25 This emphasizes the need to seek senior help and early intervention when necessary.

transfusion and may have undergone surgical procedures. Hence, it is prudent to manage them, with a multidisciplinary input, in a high-dependency unit (HDU) or intensive care unit (ICU) to ensure continuity of optimum care.

CONCLUSIONS

The algorithm we have proposed (HAEMOSTASIS) aims to help in the management of atonic PPH following vaginal delivery in a logical and systematic manner, to avoid maternal morbidity and mortality. PPH is an important cause of pregnancy-related deaths in both developing and developed countries. Atonic PPH during caesarean section can be managed by direct uterine massage, intramyometrial injection of prostaglandins as well as oxytocin infusion. Further measures include uterine compression sutures, systemic pelvic devascularization and hysterectomy. Although several case reports exist, more prospective studies are needed to study the effectiveness of tamponade balloon test and vertical and horizontal compression sutures. Optimum management of atonic PPH may help to reduce maternal morbidity and save many lives.

POSTOPERATIVE INTENSIVE CARE

It is important to remember that the management of PPH does not stop with the arrest of bleeding. Often, these patients have received multiple fluid and blood

About the Authors

Dr Chandraharan is Senior Lecturer and Dr Arulkumaran is Professor and Head at the Division of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, St. Georges Hospital Medical School, London, United Kingdom. E-mail: echandra@sghms.ac.uk, sarulkum@sghms.ac.uk

REFERENCES

1. Why Mothers Die? Triennial Report 200002. Confidential Enquiries into Maternal and Child Health. United Kingdom; 2004. 2. Arulkumaran S, Decruz B. Surgical management of severe postpartum haemorrhage. Curr Obstet Gynaecol 1999;9:101-105. 3. Hofmeyr GJ, Mohlala BK. Hypovolumic shock. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2001;15:645-662. 4. Santosa JT, Lin DW, Miller DS. Transfusion medicine in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1995;50:470-481. 5. ACOG Publication on Postpartum Haemorrhage No.243. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 1998. 6. Takagi S, Yoshida T, Togo Y, et al. The effects of intramyometrial injection of prostaglandin F2 alpha on severe postpartum haemorrhage. Prostaglandins 1976;12:565-579. 7. Toppozada M. The use of prostaglandins in postpartum haemorrhage. J Egypt Soc Obstet Gynecol 1991;17:9-18. 8. Mousa HA, Alfirevic Z. Treatment of primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(1):CD003249. 9. Lokugamage AU, Sullivan KR, Niculescu I, et al. A randomized study comparing rectally administered misoprostol versus syntometrine combined with an oxytocin infusion for cessation of postpartum hemorrhage. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:835-839. 10. Condous GS, Arulkumaran S, Symonds I, Chapman R, Sinha A, Razvi K. The tamponade test in the management of massive postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101: 767-772. 11. Johanson R, Kumar M, Obrhai M, Yuong P. Management of massive postpartum haemorrhage: Use of hydrostatic balloon catheter to avoid laparotomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2001;108:420-422. 12. Bakri YN, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar F. Tamponade balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2001;74:139-142. 13. Lynch CB, Coker A, Laval AH, Abu J, Cowen MJ. The B-Lynch surgical technique for control of massive postpartum haemorrhage: An alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases reported. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:372-376. 14. Hayman RG, Arulkumaran S, Steer PJ. Uterine compression sutures: surgical management of postpartum haemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:502-506. 15. Tamizian O, Arulkumaran S. The surgical management of postpartum haemorrhage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2002;16:81-98. 16. Cho JH, Jun HS, Lee CN 2000. Hemostatic suturing technique for uterine bleeding during caesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2000; 96:129-131. 17. Still DK. Postpartum Haemorrhage and other third stage problems. In: James DK, Steer PJ, Weiner CP, Gonik B, editors. High Risk Pregnancy Management Options. London: WB Saunders; 1999. 18. Burchell RC. Physiology of internal artery ligation. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 1968;75:642-651.

A complete list of references can be obtained upon request to the Editor.

JPOG MAY/JUN 2005 112

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Speech in ActionDocument160 pagesSpeech in ActionSplashXNo ratings yet

- Spherocytosis & Increased Risk of Thrombosis. Kam Newman, Mojtaba Akhtari, Salim Shakour, Shahriar DadkhahDocument1 pageSpherocytosis & Increased Risk of Thrombosis. Kam Newman, Mojtaba Akhtari, Salim Shakour, Shahriar DadkhahjingerbrunoNo ratings yet

- Nextier - Pharma 101 - 29-Jun-2016Document28 pagesNextier - Pharma 101 - 29-Jun-2016Ammar ImtiazNo ratings yet

- Return Demonstration: Urinary Catheterization Perineal CareDocument3 pagesReturn Demonstration: Urinary Catheterization Perineal CareDebbie beeNo ratings yet

- Excerpt: "Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won't Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care" by Marty MakaryDocument4 pagesExcerpt: "Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won't Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care" by Marty Makarywamu885No ratings yet

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome in Adults - Second Edition - 0 PDFDocument97 pagesComplex Regional Pain Syndrome in Adults - Second Edition - 0 PDFLotteDomineNo ratings yet

- ADS ADEA ANZCA NZSSD - DKA - SGLT2i - Alert - Ver July 2022Document3 pagesADS ADEA ANZCA NZSSD - DKA - SGLT2i - Alert - Ver July 2022tom.condon.02No ratings yet

- Sound Transduction EarDocument7 pagesSound Transduction Earhsc5013100% (1)

- Cognitv EmphatyDocument6 pagesCognitv EmphatyAndrea MenesesNo ratings yet

- Scrotal HerniaDocument9 pagesScrotal HerniaReymart BolagaoNo ratings yet

- JK SCIENCE: Verrucous Carcinoma of the Mobile TongueDocument3 pagesJK SCIENCE: Verrucous Carcinoma of the Mobile TonguedarsunaddictedNo ratings yet

- Book Club Guide: INVINCIBLEDocument1 pageBook Club Guide: INVINCIBLEEpicReadsNo ratings yet

- Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Medications and Dental Procedures ADADocument8 pagesAnticoagulant and Antiplatelet Medications and Dental Procedures ADADeeNo ratings yet

- Gambaran CT SCAN: (Kasus: Edh, SDH, Ich, Sah, Infark Cerebri, IvhDocument44 pagesGambaran CT SCAN: (Kasus: Edh, SDH, Ich, Sah, Infark Cerebri, Ivhfahmi rosyadiNo ratings yet

- Laughter Discussion TopicDocument3 pagesLaughter Discussion Topicjelenap221219950% (1)

- CV DermatologistDocument2 pagesCV DermatologistArys SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Daftar Obat Slow Moving Dan Ed Rawat Inap Maret 2021Document8 pagesDaftar Obat Slow Moving Dan Ed Rawat Inap Maret 2021Vima LadipaNo ratings yet

- Wallen Et Al-2006-Australian Occupational Therapy JournalDocument1 pageWallen Et Al-2006-Australian Occupational Therapy Journal胡知行No ratings yet

- Administering Corticosteroids in Neurologic Diseases3724Document12 pagesAdministering Corticosteroids in Neurologic Diseases3724Carmen BritoNo ratings yet

- Amyotrophic Lateral SclerosisDocument70 pagesAmyotrophic Lateral SclerosisLorenz Hernandez100% (1)

- Psychological Point of ViewDocument3 pagesPsychological Point of ViewForam PatelNo ratings yet

- Viral Exanthems: Sahara Tuazan AbonawasDocument75 pagesViral Exanthems: Sahara Tuazan AbonawasMarlon Cenabre Turaja100% (1)

- Influence of Cavity LiningDocument7 pagesInfluence of Cavity Liningpatel keralNo ratings yet

- Basic Principles of Pediatric Mechanical VentilationDocument39 pagesBasic Principles of Pediatric Mechanical VentilationNav KovNo ratings yet

- Pacemaker - Mayo ClinicDocument15 pagesPacemaker - Mayo ClinicShehab AhmedNo ratings yet

- Colgate Oral Care: Product RangeDocument62 pagesColgate Oral Care: Product RangeRahuls RahulsNo ratings yet

- DR Wong Teck WeeipadDocument2 pagesDR Wong Teck Weeipadtwwong68No ratings yet

- 2014 Body Code Client Information PDFDocument7 pages2014 Body Code Client Information PDFkrug100% (1)

- Presentations Sux ApnoeaDocument18 pagesPresentations Sux ApnoeaalishbaNo ratings yet

- FORMAT Discharge PlanDocument5 pagesFORMAT Discharge PlanButchay LumbabNo ratings yet