Professional Documents

Culture Documents

57 Wayne l. Rev. 473 - Sticks and Stones May Break My Bones but Extreme and Outrageous Conduct Will Never Hurt Me the Demise of Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress Claims in the Aftermath of Snyder v. Phelps - Elizabeth m. Jaffe

Uploaded by

WayneLawReviewOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

57 Wayne l. Rev. 473 - Sticks and Stones May Break My Bones but Extreme and Outrageous Conduct Will Never Hurt Me the Demise of Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress Claims in the Aftermath of Snyder v. Phelps - Elizabeth m. Jaffe

Uploaded by

WayneLawReviewCopyright:

Available Formats

STICKS AND STONES MAY BREAK MY BONES BUT EXTREME AND OUTRAGEOUS CONDUCT WILL NEVER HURT ME:

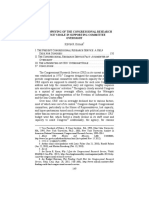

THE DEMISE OF INTENTIONAL INFLICTION OF EMOTIONAL DISTRESS CLAIMS IN THE AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS ELIZABETH M. JAFFE I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 473 II. HISTORY OF INTENTIONAL INFLICTION OF EMOTIONAL DISTRESS ........................................................................................... 476 A. The Common Law ...................................................................... 476 B. Development Through The Restatements of Torts ..................... 478 III. STATE STATUTORY CLAIMS FOR IIED ............................................ 479 IV. SNYDER V. PHELPS: THE FINAL NAIL IN THE IIED COFFIN ............. 483 V. SNYDER V. PHELPS: A FREE PASS FOR THE BULLY ......................... 488 A. The Effects of Snyder Create a Free Pass.................................. 488 B. The Constitutional Bully ............................................................ 493 VI. CONCLUSION ................................................................................... 494 Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me. Thats the First Amendment. Justice Scalia 1 I. INTRODUCTION The First Amendment came to fruition through the tireless efforts of our founding forefathers to protect an individuals right to communicate freely. 2 In todays society, many once contemplated dreams and fantasies

Associate Professor of Law, Atlantas John Marshall Law School. B.A., 1992, magna cum laude, Emory University; J.D., 1995, Washington University School of Law. I would like to thank my research assistant, Thomas Rainey, for his assistance with this article. I would also like to dedicate this article to my parents, Dr. Steven L. Jaffe, and the late Roanne L. Jaffe. 1. Oral Argument at 57:12, Schenck v. Pro-Choice Network, 519 U.S. 357 (1997), available at http://www.oyez.org/cases/1990-1999/1996/1996_95_1065/argument. 2. Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375, 391-92 (1962). [T]he purpose of the First Amendment includes the need[] . . . to protect parties in the free publication of matters of public concern, to secure their right to a free discussion of public events and public measures, and to enable every citizen at any time to bring the government and any person in authority to the bar of public opinion by any just criticism upon their conduct in the exercise of the authority which the people have conferred upon them. Id. at 392 (internal citation omitted).

473

474

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

for methods of communication have developed into reality. With the click of a mouse or the tap of a finger, individuals are able to respond to email, read the newspaper (and post a comment on the substance of the article), order Chinese food, and connect via various websites including Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. As a result of the numerous technological advances, contemporary societys understanding and use of these various methods of communication has changed significantly. However, the law governing the effects stemming from these new methods of communication has yet to keep pace with the technological advances in societys ability to communicate. Imagine if after a day of session during the First Congress of the United States in 1789, 3 and desiring to further discuss the days debates, two of the members of the First Congress act as follows: Patrick Henry turns to James Madison and says I support your position regarding your proposed draft and would like to further discuss this with you this evening. I will text you later to set up a time to convene. Surely Representative Madison would be left with a rather puzzled look on his face as to what his fellow congressional member meant by I will text you. Perhaps Representative Madison would have understood the exchange to mean he would receive an actual text 4 message from his colleague. Next, imagine if, as promised, Representative Henry delivered the text message to Representative Madison later that same evening. The message began by thanking Representative Madison for all of his work to date regarding the proposed bill of individual rights and further proposed an agenda and possible dates for the meeting. The concluding paragraph expressed the extreme importance of the subject matter and further asserted that both men had a duty to ensure the outrageous proposals of their various colleagues did not hinder the needs of the current citizens of the new nation nor the rights of the future generations. If Representative Madison was unsure as to the meaning of text, he likely considered these concluding statements to mean his proposal for codifying the various expressive freedoms comprised the outlying boundaries of the natural rights each citizen forgoes when joining the new nation. Moreover, the belief that anything less inevitably aroused the greatest sense of responsibility in Representative Henry to ensure that

3. National Archives, The Charters of Freedom A New World is at HandBill of Rights, http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/bill_of_rights.html (last visited Nov. 22, 2011). 4. Definition of Text, MERRIAM-WEBSTER ONLINE DICTIONARY, available at www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/text (last visited Nov. 22, 2011) (defining text as the main body of printed or written matter on a page).

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

475

these rights were not diminished by shockingly bad or excessive[ly] 5 restrictive counter proposals. Regardless of Representative Madisons understanding of his colleagues comments, this hypothetical exchange demonstrates that the meaning of wordsand their usechanges with societys application of the message intended to be exchanged. Fast forward a few hundred years, and these phrases are now part of the common day language. A text is now a regularly used and often even a necessary form of communication. Yet, what is the cost for these new creature features and necessities? Does the modern abilityand constitutional rightto exchange ideas in the public forum mean the idiom of sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me 6 must also change? To succeed on the tort claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED), a plaintiff must show the defendant intentionally or recklessly engaged in extreme and outrageous conduct that caused the plaintiff to suffer severe emotional distress. 7 While the Supreme Court has not declared speech alone sufficient to sustain a claim for IIED, it is generally accepted that extreme or outrageous speech can justify a claim for IIED. 8 However, with the Supreme Courts recent holding in Snyder v. Phelps, the claim is all but obsolete, 9 because [t]he Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment . . . can serve as a defense in state tort suits, including suits for intentional infliction of emotional distress. 10

5. Definition 1 of Outrageous, OXFORD DICTIONARIES, available at http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/outrageous?region=us (last visited Nov. 22, 2011) (defining outrageous). 6. CAMBRIDGE IDIOMS DICTIONARY 400 (2d ed. 1998) (defining sticks and stones may break my bones (but names will never hurt me)). 7. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS 46 (1965). 8. W. PAGE KEETON ET AL, PROSSER & KEETON ON TORTS, 12, 60 (5th ed. 1985); accord RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS 46, ill. 1 (1965) (As a practical joke, A falsely tells B that her husband has been badly injured in an accident, and is in the hospital with both legs broken. B suffers severe emotional distress. A is subject to liability to B for her emotional distress.); Snyder v. Phelps, 131 S. Ct. 1207, 1223 (2011) (Alito, J. dissenting) (although this Court has not decided the question, I think it is clear that the First Amendment does not entirely preclude liability for the intentional infliction of emotional distress by means of speech.). 9. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1219 (setting aside jury verdict imposing tort liability . . . for intentional infliction of emotional distress). See also Alan Brownstein & Vikram David Amar, Afterthoughts on Snyder v. Phelps, 2011 CARDOZO L. REV. DE NOVO 43 (arguing the Courts decision to grant review of the Fourth Circuits reversal questionable as the decision added little to the development of [the] free speech doctrine). Granting review may have raised false expectations of redress in the plaintiff, the father of an American soldier killed in the line of duty, a person who surely had suffered enough and did not need the High Court rubbing salt in his wounds. Id. (emphasis added). 10. Snyder, 131 S.Ct. at 1215.

476

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

Moreover, the words extreme and outrageous have taken on a form of their own in contemporary society. These once strong and seldom used words have become badges of honor considered to be terms of art referring to conduct departing from the accepted norms of the previous generation. 11 As a result of contemporary societys advancement in understandingand subsequently applyingthe elements of extreme or outrageous in the context of a claim for IIED, a jury is unlikely to be neutral with respect to the content of the speech, posing a real danger of becoming an instrument for the suppression of vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasant expression. 12 Therefore, the risk of misapplication by a jury of ones peers must yield, and an injured party must tolerate insulting, and even outrageous, speech in order to provide adequate breathing space to the freedoms protected by the First Amendment. 13 II. HISTORY OF INTENTIONAL INFLICTION OF EMOTIONAL DISTRESS A. The Common Law Liability for pure emotional harm alone was neither a favorable cause of action under English common law, nor in existence at the time the First Amendment protections for speech became a reality. 14 Despite scattered hints of a willingness to compensate an aggrieved party of the basis of mental anguish intentionally inflicted by the person of another, the common law generally did not accept a plaintiffs attempt to recovery solely on the grounds of emotional harm. 15 In Lynch v. Knight, Lord Wensley Dale announced the general view of a claim seeking redress of emotional harm: Mental pain or anxiety the law cannot value, and does

11. Many facets of contemporary life are now entitled extreme. In addition, contemporary society has decided saying, or more importantly typing the entire word extreme to be too cumbersome and has simply removed all letters of the word except one: X. One example of this is now known as the X-Games. Originally dubbed the Extreme Games in its 1995 debut, the extreme sports competition is now more commonly referred to as the X Games or the Look Ma, No Hands Olympics. Kate Pickert, A Brief History of The X Games, TIME, Jan 22, 2009, http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1873166,00.html (last visited Mar. 4, 2012). 12. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1219 (quoting Bose Corp. v. Consumers Union of United States, Inc., 466 U.S. 485, 510 (1984)) (alterations in original & citation omitted). 13. Id. (quoting Boos v. Barry, 485 U.S. 312, 322 (1988)). 14. Nancy Levit, Ethereal Torts, 61 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 136, 140 (1992) (Historically, tort law compensated only direct and tangible injuries to persons or property.). 15. Id.

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

477

not pretend to redress, when the unlawful act complained of causes that alone. 16 A few years later, in Wilkinson v. Downton, the English courts expressly stated the implied application of the laws acceptance of a claim that rested solely on emotional harm. 17 Although the legal term of artIIEDwas not coined by Justice Wright in his opinion in Wilkinson, the term intentional infliction of mental shock laid the foundation for the modern day claim of IIED. 18 In Wilkinson, the plaintiff sued for what the defendant regarded as a practical joke. 19 The defendant told the plaintiff that he was charged by her husband with a message to her to the effect that her husband was smashed up in an accident, and was lying at The Elms at Leytonstone with both legs broken, and that she was to go at once in a cab with two pillows to fetch him home. 20 Despite the information conveyed being false, the plaintiff suffered a violent shock to her nervous system, producing vomiting and other more serious and permanent physical consequences at one time threatening her reason, and entailing weeks of suffering and incapacity to her . . . . 21 In finding in favor of the plaintiff with a monetary award, the court stated: The defendant has, as I assume for the moment, willfully done an act calculated to cause physical harm to the plaintiffthat is to say, to infringe her legal right to personal safety, and has in fact thereby caused physical harm to her. That proposition without more appears to me to state a good cause of action, there being no justification alleged for the act. This willful injuria is in law malicious, although no malicious purpose to cause the harm

16. Lynch v. Knight, 11 Eng. Rep. 854, 864 (1861). 17. Wilkinson v. Downton, 2 QB 57 (1897); see, e.g., Kathleen M. Turezyn, When Circumstances Provides a Guarantee of Genuineness: Permitting Recovery For PreImpact Emotional Distress, 28 B.C. L. REV. 881, 887 (1987) (An English court, however, in the seminal case of Wilkinson v. Downton, recognized the intentional infliction of emotional distress as a distinct and independent tort. Although American courts originally were reluctant to follow the English precedent, by 1930 intentional infliction of emotional distress had achieved general acceptance as an independent cause of action.); Geoffrey Christopher Rapp, Defense Against Outrage and the Perils of Parasitic Torts, 45 GA. L. REV. 107, 134 (2010) (The traditional concern expressed in Wilkinson and thereafter associated with recognizing emotional harm-based torts in the absence of physical contact (or assault) was that claims would be too easy to allege.). 18. Wilkinson, 2 QB at 57. 19. Id. 20. Id. 21. Id. at 58.

478

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

which was caused nor any motive of spite is imputed to the defendant. 22 B. Development Through The Restatements of Torts The first Restatement of Torts did not recognize liability for intentional conduct which is intended . . . to cause only a mental or emotional disturbance to another[.] 23 In response to the position taken by the drafters of the first Restatement of Torts, the legal academic literature of the 1930s expressed its dismay with this non-inclusion, and called for the recognition of a civil cause of action protecting the mental well-being of would-be plaintiffs. 24 Thereafter, in 1948, the American Law Institute reversed its position and restated the law under section 46. 25 The revision imposed liability in instances where [o]ne who, without privilege to do so, intentionally causes emotional distress to another is liable (a) for such emotional distress, and (b) for bodily harm resulting from it. 26 In 1965, the Restatement (Second) of Torts accepted the revision and codified the cause of action for IIED. However, this general acceptance of the claim for IIED did not come without limitations. The limitations and application of the claim for IIED are best illustrated in the comments to the Second Restatement of Torts: The liability clearly does not extend to mere insults, indignities, threats, annoyances, petty oppressions, or other trivialities. The rough edges of our society are still in need of a good deal of filing down, and in the meantime plaintiffs must necessarily be expected and required to be hardened to a certain amount of rough language, and to occasional acts that are defiantly inconsiderate and unkind. There is no occasion for the law to intervene in every case where some ones feelings are hurt. There must still be freedom to express an unflattering opinion,

22. Id. at 58-59. 23. RESTATEMENT (FIRST) OF TORTS 46 (1934). 24. See, e.g., Calvert Magruder, Mental and Emotional Disturbance in the Law of Torts, 49 HARV. L. REV. 1033 (1936); William L. Prosser, Intentional Infliction of Mental Suffering: A New Tort, 37 MICH. L. REV. 874 (1939). 25. Daniel Bivelber, The Right to Minimum Social Decency and The Limits of Evenhandedness: Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress by Outrageous Conduct, 82 COLUM. L. REV. 42, 43 (1982). 26. RESTATEMENT OF THE LAW, SUPPLEMENT, TORTS 46 (1948).

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

479

and some safety value must be left through which irascible tempers may blow off relatively harmless steam. 27 In keeping with the refining and polishing the previous version endured, the Restatement (Third) of Torts now defines a claim of Intentional (Or Reckless) Infliction of Emotional Disturbance as: [a]n actor who by extreme and outrageous conduct intentionally or recklessly causes severe emotional disturbance to another is subject to liability for that emotional disturbance and if the emotional disturbance causes bodily harm, also for the bodily harm. 28 III. STATE STATUTORY CLAIMS FOR IIED Today, IIED is recognized as a recoverable cause of action in all U.S. jurisdictions. 29 As a state law claim, IIED claims vary from state to state. 30 To sustain liability for IIED, the majority of the States require a finding of extreme and outrageous conduct. 31 Despite this general recognition among the states 32 and territories, 33 most courts do not accept the claim, and generally deny recovery on grounds of mental anguish alone. 34 Moreover, under the doctrine of preemption, 35 any state law

27. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS 46, cmt. d (1965). 28. RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TORTS 45 (Tentative Draft No. 5, 2007). 29. John J. Kircher, The Four Faces of Tort Law: Liability for Emotional Harm, 90 MARQ. L. REV. 789, 806 (2007) (All states have recognized intentional infliction of emotional distress as an independent tort and have adopted Restatement (Second) of Torts section 46 in some form). To support this claim, Professor Kircher includes a state by state survey of the claim of IIED highlighting the required elements of the claim. Id. at 852-82. 30. See id. at 852-82. 31. See id. 32. See id. 33. Manns v. Leather Shop Inc., 960 F. Supp. 925, 930 (D.V.I. 1997) (applying RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS 46 standard for IIED claim); Abuan v. Gen. Elec. Co., 1992 WL 535958, at *5 (D. Guam 1992) (Intentional infliction of emotional distress by extreme or outrageous conduct requires conduct exceeding all bounds usually tolerated by decent society, of a nature which is especially calculated to cause, and does cause, mental distress of a very serious kind.) (quoting PROSSER & KEETON, supra note 8, 12); Dynamic Image Tech., Inc. v. United States, 18 F. Supp. 2d 146, (D.P.R. 1998) (asserting [a] claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress is cognizable under Puerto Rico law.) (citing Santiago-Ramirez v. Secy of Dept. of Def., 62 F.3d 445, 448 (1st Cir. 1995)); Charfauros v. Bd. of Elections, 5 N. Mar. I. Commw. 188 (N. Mar. I. 1998) (recognizing cause of action for the intentional infliction of emotional distress requires proof of four elements.). 34. See e.g., Ruth v. Fletcher, 377 S.E.2d 412, 415-16 (Va. 1989) (Because of the risk inherent in torts where injury to the mind or emotions is claimed, [] such torts [are] not favored in the law . . . because of the fact that the fright or mental shock may be so

480

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

infringing on constitutional guarantees must give way to the inalienable rights the framers afforded to all citizens. 36 As no federal law specifically entitles an aggrieved party to relief for emotional harm as an independent claim, state legislative attempts to protect, and compensate, victims for emotional harm intentionally inflicted by extreme or outrageous speech appears to work so long as constitutional concerns are not at issue. Georgia law has long recognized the tort claim of IIED. 37 In Georgia, to prevail on a claim for IIED, an aggrieved party must show: (1) intentional or reckless conduct by the defendant with a disregard for the rights of others; (2) the conduct was outrageous and extreme; (3) a causal connection between the extreme and outrageous conduct and the emotional distress alleged; and (4) severe emotional distress. 38 Significant outrage in the extreme and outrageous speech alleged is the gravamen of a plaintiffs claim for IIED. 39 In addition, the test to

easily feigned without detection, the court should allow no recovery in a doubtful case.) (quoting Bowles v. May, 166 S.E. 550, 557 (Va. 1932)); Croom v. Younts, 913 S.W.2d 283, 287 (Ark. 1996) (asserting Arkansas courts take a strict approach and give a narrow view to the tort of outrage); Homan v. Goyal, 711 A.2d 812, 818 (D.C. Cir. 1998) (citing Drejza v. Vaccaro, 650 A.2d 1308, 1312 (D.C. Cir. 1994)) ([T]he requirement of outrageous is not an easy one to meet. Liability will not be imposed for mere insults, indignities, threats, annoyances, petty oppressions, or other trivialities. Against a large part of the frictions and irritations and clashing of temperaments incident to participation in a community life, a certain toughness of the mental hide is a better protection than the law could ever be.) (citations & internal quotations omitted); Christensen v. Superior Court, 820 P.2d 181, 203 (Cal. 1991) (The law limits claims of intentional infliction of emotional distress to egregious conducted toward plaintiff proximately caused by defendant. [T]o the extent such recovery had been allowed, it has been limited to the most extreme cases of violent attack, where there is some especial likelihood of fright or shock.) (internal citations and quotations omitted). 35. U.S. CONST. art. VI (This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.). See generally Gade v. Natl Solid Waste Mgmt. Assn, 505 U.S. 88, 108 (1992) (asserting the doctrine of preemption is derived from the Supremacy Clause of Article VI). 36. Assoc. Press v. Natl Labor Relations Bd., 301 U.S. 103, 134-35 (1937) ([T]he framers of the Bill of Rights, regarding certain liberties as so vital that legislative denial of them should be specifically foreclosed, provided by the First Amendment: Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press[.]). 37. Chapman v. W. Union Tel. Co., 15 S.E. 901, 904 (Ga. 1892) (asserting statutory damages for an entire injury [] to the peace, happiness, or feelings of the plaintiff . . . declare the pre-existing law.); Dunn v. W. Union Tel. Co., 59 S.E. 189, 191-92 (Ga. App. 1907) (distinguishing the malicious and intentional tort [of IIED from]...a merely negligent, though wrongful, omission.). 38. See Bridges v. Winn-Dixie Atlanta, Inc., 335 S.E.2d 445, 447 (Ga. App. 1985). 39. Potts v. UAP-GA AG Chem., Inc., 567 S.E.2d 316 (Ga. App. 2002).

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

481

determine outrageous conduct is a question of law, and requires the case is one which the recitation of the facts to an average member of the community would arouse his resentment against the actor, and leave him to exclaim Outrageous! 40 Once the court determines the question of law regarding the required level of extreme and outrageous speech and determines a reasonable person could also find the speech meets these requirements, the jury must make the ultimate determination regarding liability on the facts presented. 41 In California, civil liability is imposed and recovery is granted on the basis of the plaintiff suffering physical injuries as the result of the defendants intentional actions causing the plaintiff to suffer serious mental distress. 42 A victims prima facie claim for IIED requires a showing that: (1) extreme and outrageous conduct by the defendant with the intention of causing, or reckless disregard of the probability of causing, emotional distress; (2) the plaintiffs suffering severe or extreme emotional distress; and (3) actual and proximate causation of the emotional distress by the defendants outrageous conduct. 43 However, California limits recovery on a claim for IIED by generally requiring the plaintiff to physically and personally be affected by the defendants conduct at the time the defendant engaged in the extreme or outrageous activity. 44 Moreover, the conduct complained of must be predicated on the defendants knowing desire to engage in the extreme and outrageous conduct that is tailored to achieve the results the plaintiff seeks liability for. 45 Thus, a claim for IIED in California is limited to, and reserved for

40. Yarbray v. S. Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 409 S.E.2d 835, 837 (Ga. 1991) (quoting RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS 46(1), cmt. d (1965)). 41. Gordon v. Frost, 388 S.E.2d 362, 366-67 (Ga. App. 1989) (Because there was some evidence to support the jurys determination that defendants intentionally inflicted emotional distress upon [the plaintiff], the trial court was not authorized to grant defendants judgment notwithstanding the verdict. While the trial court may act as a thirteenth juror . . . it may not assume this role to weigh the evidence[.]). 42. Cf. Emden v. Vitz, 198 P.2d 696, 699 (Cal. Dist. Ct. App. 1948) (It is a matter of general knowledge that an attack of sudden fright, or an exposure to imminent peril, has produced in individuals a complete change in their nervous system, and rendered one who was physically strong and vigorous weak and timid. Such a result must be regarded as an injury to the body rather than to the mind, even though the mind be at the same time injuriously affected.). 43. Cervantez v. J. C. Penney Co., 595 P.2d 975, 983 (Cal. 1979) (quoting Fletcher v. W. Natl Life Ins. Co., 10 Cal. App. 3d 376, 394 (1970)). 44. Huggins v. Longs Drug Stores California, Inc., 862 P.2d 148, 152 (Cal. 1993) (denying liability on a claim of IIED to the parents of a patient who was provided medical treatment by the defendants because [c]ourts have not extended . . . directvictim cause of action to emotional distress which is derived solely from a reaction to anothers injury.) (alteration in original). 45. Ess v. Eskaton Prop., Inc., 118 Cal. Rptr. 2d 240, 246-47 (Cal. Ct. App. 2002).

482

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

the most extreme cases of violent attack, where there is some especial likelihood of fright or shock. 46 In Montana, an individuals suffering from emotional distress due to the extreme or outrageous conduct of the person of another has the ability to sustain a standalone civil cause of action for the claim of IIED. 47 In adopting the Restatement (Second) of Torts definition of severe emotional distress, Montana law imposes liability: where the emotional distress has in fact resulted and where it is severe. Emotional distress passes under various names, such as mental suffering, mental anguish, mental or nervous shock or the like. It includes all highly unpleasant mental reactions, such as fright, horror, grief, shame, humiliation, embarrassment, anger, chagrin, disappointment, worry, and nausea. 48 However, in adopting this position, Montana law acknowledges that [c]omplete emotional tranquility is seldom attainable in this world, and some degree of transient and trivial emotional distress is a part of the price of living among people. 49 Montana courts do not require the victim-plaintiff to plead the seriousness or severity of the emotional distress in order to have the amount of liability determined by the trier.50 Therefore, in Montana, the severity of the harm [determines] the amount, not the availability, of recovery under a claim for IIED. 51 In Maryland, where the underlying factual events of Snyder occurred, a claim for IIED is an independent tort. 52 As such, a plaintiff has the ability to sustain a valid cause of action for IIED, absent any manifest physical injury when: (1) the conduct complained of is intentional or reckless; (2) the conduct is extreme and outrageous; (3) a causal connection exists between the alleged emotional distress and the accused wrongful actions; and (4) the plaintiffs emotional distress is

46. Ochoa v. Superior Court, 703 P.2d 1, 4 n.5 (Cal. 1985) (quoting PROSSER & KEETON, supra note 8, at 66). 47. Sacco v. High Country Indep. Press, Inc., 896 P.2d 411, 427 (Mont. 1995) (holding that a claim for IIED can be pled as a separate cause of action in the courts of Montana.) (emphasis omitted). 48. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS, 46, cmt. j (1965); Sacco, 896 P.2d at 427. 49. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS, 46, cmt. j (1965). 50. Jacobsen v. Allstate Ins. Co., 215 P.3d 649 (Mont. 2009) (overruling First Bank (N.A.)-Billings v. Clark, 771 P.2d 84 (1989); Johnson v. Supersave Markets, Inc., 686 P.2d 209 (1984); Noonan v. First Bank Butte, 740 P.2d 631 (1987)). 51. Vortex Fishing Sys., Inc. v. Foss, 38 P.3d 836, 33 (Mont. 2001) (quoting Chatman v. Slagle, 107 F.2d 380, 385 (6th Cir. 1997)). 52. Harris v. Jones, 380 A.2d 611, 614 (Md. 1977).

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

483

severe. 53 To determine the extent of the extreme and outrageous conduct, Maryland requires the conduct at issue be considered in the context of the factual situation that gives rise to the claim for IIED, with [t]he personality of the individual to whom the misconduct is directed also factoring in the determination. 54 Simply put, extreme and outrageous conduct exists only if the average member of the community must regard the defendants conduct as being a complete denial of the plaintiffs dignity as a person. 55 IV. SNYDER V. PHELPS: THE FINAL NAIL IN THE IIED COFFIN In Snyder v. Phelps, the Supreme Court of the United States addressed the issue of whether the First Amendment shields the [Westboro Baptist Church] members from tort liability for their speech. 56 In Snyder, the plaintiff, the father of Marine Lance Corporal Matthew Snyder (Snyder), sought to recover damages for the IIED resulting from picketing at his sons funeral. 57 The members of Westboro Baptist Church (Westboro), led by Fred Phelps, picketed near the funeral to demonstrate their view that the United States is overly tolerant of sin and that God kills American soldiers as punishment.58 Westboro, in complying with the local authorities direction to stay within the area set aside for the groups demonstration, held signs stating: God Hates the USA/Thank God for 9/11, America is Doomed, Dont Pray for the USA, Thank God for IEDs, Thank God for Dead Soldiers, Pope in Hell, Priests Rape Boys, God Hates Fags, Youre Going to Hell, and God Hates You. 59 A jury found in favor of Snyder on the IIED claim and held Westboro liable for $2.9 million in compensatory damages and $8 million in punitive damages. 60 The district court remitted the punitive damages award to $2.1 million, but left the remainder of the jury verdict

53. Id. (adopting the element of IIED from Womack v. Eldridge, 210 S.E.2d 145 (Va. 1974)). 54. Id. (There is a difference between violent and vile profanity addressed to a lady, and the same language to a Butte miner and a United States marine.) (quoting Prosser, supra note 24, at 887)). 55. Dick v. Mercantile-Safe Deposit & Trust Co., 492 A.2d 674, 677 (Md. 1985) (alteration in original) (citation omitted). 56. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1213. 57. Id. 58. Id. 59. Id. 60. Snyder v. Phelps, 533 F. Supp. 2d 567, 589 (D. Md. 2008), overruled by Synder v. Phelps, 580 F.3d 206, 211 (4th Cir. 2009).

484

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

intact. 61 Westboro appealed claiming the church was entitled to judgment as a matter of law as the speech (the statements on the signs) was protected by the First Amendment. 62 The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals found in favor of Westboro, concluding that the statements were on matters of public concern, were not provably false, and were expressed solely through hyperbolic rhetoric. 63 Snyder then appealed to the United States Supreme Court, and after granting certiorari, the Supreme Court set aside the jury verdict imposing tort liability on Westboro for intentional infliction of emotional distress. 64 The Supreme Court began its analysis noting, [t]o succeed on a claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress . . . a plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant intentionally or recklessly engaged in extreme and outrageous conduct that caused the plaintiff to suffer severe emotional distress. 65 Citing to Hustler Magazine v. Falwell, 66 the Court recognized The Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speechcan serve as a defense in state tort suits, including suits for intentional infliction of emotional distress. 67 The Court stated [w]hether the First Amendment prohibits holding Westboro liable for its speech in this case turns largely on whether that speech is of public or private concern, as determined by all the circumstances of the case. 68 Recognizing that speech on matters of public concern lies at the heart of First Amendment protection, the Supreme Court pointed out that not all speech is of equal First Amendment importance, however, and where matters of purely private significance are at issue, First Amendment protections are often less rigorous . . . because restricting speech on purely private matters does not implicate the same constitutional concerns as limiting speech on matters of public interest. 69 The Court

61. Snyder, 533 F. Supp. 2d at 597. 62. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1214. 63. Id. 64. Id. at 1215. 65. Id. 66. Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988) (holding public figures unable to recover damages under IIED for publication of a caricature depicting plaintiff in a sexual parody). 67. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1215. 68. Id. 69. Id.; Snyder, 580 F.3d at 221-22 (vacating judgment and awarding new trial for erroneous jury instruction charging the jury with the task to determine a purely legal issue, namely, the scope of protection afforded to speech under the First Amendment). The jury instruction at issue, which the district court allowed over defendants objections, required the jury to determine whether the Defendants speech was directed specifically at the Snyder family, and, if so, whether it was so offensive and shocking as to not be

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

485

further explained that the inappropriate or controversial character of a statement is irrelevant to the question [of] whether it deals with a matter of public concern. 70 After reviewing the record and deciding whether the speech is of public or private concern by examining the content, form and context of that speech, the Court concluded the content of Westboros signs related to issues of interest to society at large. 71 The Court noted [w]hile these messages [America is Doomed, Semper Fi Fags, Thank God for Dead Soldiers, Youre Going to Hell, Priests Rape Boys, etc.] may fall short of refined social or political commentary, the issues they highlightthe political and moral conduct of the United States and its citizens, the fate of our Nation, homosexuality in the military, and scandals involving the Catholic clergyare matters of public import. 72 Moreover, the Court reasoned that even if some of the signs specifically contained messages directed at Matthew Snyder or his family, that would not change the fact that the overall thrust and dominant theme of Westboros demonstration spoke to broader public issues. 73 The Supreme Court rejected Snyders argument that Westboro personally attacked Snyder and his family, and noted Westboros speech

entitled to First Amendment protection. Id. at 221. Jury Instruction No. 21 read as follows: You must balance the Defendants expression of religious belief with another citizens right to privacy and his or her right to be free from intentional, reckless, or extreme and outrageous conduct causing him or her severe emotional distress. Id. As such, it appears a jury of ones peers is unable to determine the scope of First Amendment protection provided words in relation to the extreme and outrageous speech directed toward the father of a deceased Marine. This holding and application appears to reaffirm the Courts jurisprudence that the First Amendment is superior to the Seventh Amendment. Cf. New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 285, n.26 (1964) (The Seventh Amendment does not . . . preclude [the Supreme Court] from determining whether governing rules of federal law have been properly applied to the facts.); Ellen E. Sward, Legislative Courts, Article III, and the Seventh Amendment, 77 N.C. L. REV. 1037, 1104 (1999) (arguing error lies in [t]he Courts treatment of these two amendments may be based on a view that the First Amendment right of free speech is more important than the Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial. Free speech, after all, is essential to the functioning of a democracy, but democracies function through the world without a civil jury.) (internal citation omitted). Ned Snow, Judges Playing Jury: Constitutional Conflicts in Deciding Fair Use on Summary Judgment, 44 U.C. DAVIS L. REV. 483, 555 (2010) (arguing that [t]reating fair use as a pure issue of law violates the Seventh Amendment right to a civil jury and threatens the First Amendment right of free speech . . . . Judges have invaded the constitutional province of the jury, stripping away ordinary citizens from the process due in cases where the law deprives individual members of its public of all their property). 70. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1215. 71. Id. at 1216. 72. Id. at 1217. 73. Id.

486

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

was not contrived to protect speech on a private matter disguised as speech on a public matter as Westboro had been actively engaged in speaking on the subjects in its picketing long before it became aware of Matthew Snyder, and there can be no serious claim that Westboros picketing did not represent its honestly believed views on public issues. 74 While the Court acknowledged that the record made it clear the applicable legal termemotional distressfailed to fully capture the anguish suffered by Snyder, Westboro conducted its picketing peacefully on matters of public concern at a public place adjacent to a public street. 75 Moreover, a public space adjacent to a public street is afforded a special position for First Amendment protection as public streets and sidewalks have historically been used for public assembly and debate. 76 Although Maryland now has a law in place which places specific restrictions on funeral picketing, 77 the Court noted the law was not in effect at the time of Westboros picketing, and thus Westboro had the right to be where they were since they notified the local authorities of their intent to protest at the funeral and fully complied with the police instruction about where they could picket. 78 Recognizing the issue at hand was what Westboro said [on the picket signs] that exposed it to tort damages, the Court reiterated [if] there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable. 79 At the original trial, the jury held Westboro liable for IIED because the jury determined the picketing was outrageous. 80 The Supreme Court, however, cited to Hustler Magazine v. Falwell, noting [o]utrageousness . . . is a highly malleable standard with an inherent subjectiveness about it which would allow a jury to impose liability on the basis of the jurors tastes or views, or perhaps on their dislike of a particular expression.81 And while the jury certainly found Westboros expressions unpleasant,

74. Id. 75. Id. at 1218. 76. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1218. 77. MD. CODE ANN., CRIM. LAW 10-205 (West 2011) (approved May 19, 2011, effective date Oct. 1, 2011) (extending the free speech zone for picketing at a funeral from one hundred feet to 550 feet of a funeral, burial, memorial service, or funeral procession that is targeted at one or more persons attending the funeral, burial, memorial service, or funeral procession). 78. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1218. 79. Id. at 1219 (quoting Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397, 414 (1989)). 80. Id. 81. Id. (quoting Hustler Magazine, 485 U.S. at 55).

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

487

the Supreme Court quoted its opinion in Boos v. Barry, stating in public debate [we] must tolerate insulting, and even outrageous speech in order provide adequate breathing space to the freedoms protected by the First Amendment. 82 As such, [w]hat Westboro said, in the whole context of how and where it chose to say it, is entitled to special protection under the First Amendment, and that protection cannot be overcome by a jury finding that the picketing was outrageous. 83 Despite the majority of the Court in Snyder denying the fathers IIED claim, the lone dissenter, Justice Alito, noted the profound national commitment to free and open debate is not a license for the vicious verbal assault that occurred in this case . . . [and as such] the First Amendment does not entirely preclude liability for the intentional infliction of emotional distress by means of speech. 84 This statement by Justice Alito appears to signify that the Court has, in fact, placed the final nail in the IIED coffin. Although the Supreme Court specifically noted its holding was narrow, the Court reiterated: Speech is powerful. It can stir people to action, move them to tears of both joy and sorrow, andas it did hereinflict great pain. On the facts before us, we cannot react to that pain by punishing the speaker. As a Nation we have chosen a different courseto protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate. That choice requires that we shield Westboro from tort liability for its picketing in this case. 85 While the majority based their holding on First Amendment grounds of concern for public or private speech, does the holding signify that so long as the defendant can couch the extreme and outrageous speech or conduct on the grounds of public concern, an aggrieved plaintiff will be barred from recovery? Moreover, as noted above, what constitutes public concern in contemporary America? Surely, the public concern originally envisioned by the Framers and our forefathers is not the same public concern that appears today. If the signs Westboro used when protesting the funeral receive First Amendment protection, then why must a billboard depicting a man holding a silhouette of an infant child

82. 83. 84. 85.

Id. (quoting Boos, 485 U.S. at 322). Id. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1222-23 (Alito, J. dissenting). Id. at 1220.

488

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

be taken down? 86 There is little dispute that the issue regarding a mothers right to control her body is a current public concern in contemporary America. Thus, applying Snyder, the billboard qualifies as constitutional speech and any harm stemming from the message requires the victim to remember that extreme or outrageous conduct, in the form of a billboard message, will never hurt. V. SNYDER V. PHELPS: A FREE PASS FOR THE BULLY A. The Effects of Snyder Create a Free Pass What did Snyder do to the claim of IIED? Does a bully now have a free pass to inflict pain upon the victim so long as the bully provides notice of his or her intent to harm and complies with any instructions affixed by regulatory individuals? 87 Even worse, is a bully now safe and essentially free from liabilityso long as an established pattern of previous activity exists, 88 the harm is limited in time, 89 the manner of delivery is restricted, 90 and the harm to another does not disturb many others? 91 Justice Alitos dissent in Snyder reiterated the principle that to satisfy a claim for IIED, the plaintiff must establish that the defendants conduct was so outrageous in character, and so extreme in degree, as to go beyond all possible bounds of decency, and to be regarded as atrocious,

86. Judge Tells Boyfriend to Remove Abortion Billboard, ATL. J.-CONST. (June 23, 2011, 9:41 PM), http://www.ajc.com/news/nation-world/judge-tells-boyfriend-to986023.html. 87. See Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1213. The church had notified the authorities in advance of its intent to picket at the time of the funeral, and the picketers complied with police instructions in staging their demonstration. Id. 88. See id. In the more than 20 years that the members of Westboro Baptist have publicized their message, they have picketed nearly 600 funerals. Id. (citation omitted). 89. Id. The Westboro picketers displayed their signs for about 30 minutes before the funeral began[.] Id. 90. Id. None of the picketers entered church property or went to the cemetery. They did not yell or use profanity, and there was no violence associated with the picketing. Id. (citation omitted). This Article does not focus on the church members additional compliance, but one must not forget that future application of these very facts could include entry into an area open to the public, or other legally acceptable methods not employed by the Westboro members. However, maybe under escalated facts a new test for protecting individuals from extreme and outrageous conduct intending to harm another will produce a result that deters similar future behavior. 91. Id. at 1213-14. Albert Snyder, the father of the deceased Marine, testified . . . he did not see what was written on the signs until later that night, while watching a news broadcast covering the event. Id.

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

489

and utterly intolerable in a civilized community. 92 Noting the elements of an IIED claim are difficult to meet, Justice Alito pointed out Westboro did not dispute that Mr. Snyder suffered wounds that are truly severe and incapable of healing themselves. Nor did they dispute that their speech was so outrageous in character, and so extreme in degree, as to go beyond all possible bounds of decency, and to be regarded as atrocious, and utterly intolerable in a civilized community. 93 Rather, Westboro claimed the First Amendment allowed them to engage in such extreme and outrageous conduct. 94 Justice Alito further noted, [t]his Court has recognized that words may by their very utterance inflict injury and that the First Amendment does not shield utterances that form no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality. 95 Certainly a bully can use words that by their very utterance inflict injury. But does the majoritys holding in Snyder now permit the use of hateful words with the guise that the words are simply shielded by the First Amendment? In recognizing that the speech used by Westboro amounted to a brutal attack on Matthew Snyder, Justice Alito pointed out that the attack was part of Westboros plan to attract public attention and warrant First Amendment protection. 96 The Westboro members devised a strategy whereby they protested at almost six hundred military funerals and have also picketed [at] funerals of police officers, firefighters, and the victims of natural disasters, accidents, and even shocking crimes. 97 To ensure public attention, Westboro issues press releases prior to the picketing. 98 As aptly explained by Justice Alito, [t]his strategy works because it is expected that [Westboros] verbal assaults will wound the family and friends of the deceased and because the media is irresistibly drawn to the sight of persons who are visibly in grief. 99 Moreover, since Westboro announced their intent to picket Snyders funeral because God Almighty killed Lance Cpl. Snyder. He died in shame, not honorfor a fag nation cursed by God . . . Now in Hellsine

92. Id. at 1223 (Alito, J. dissenting) (quoting Harris v. Jones 380 A.2d 611, 616 (1977)). 93. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1223 (Alito, J. dissenting) (citations omitted) (internal quotation marks omitted). 94. Id. 95. Id. (quoting Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, 572 (1942)). 96. Id. 97. Id. at 1224. 98. Id. 99. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1224.

490

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

die, the announcement guaranteed that Matthews [Snyders] funeral would be transformed into a raucous media event and began the wounding process. 100 It is as if the majority of the Court is saying, so long as one provides notice, it is acceptable to use harmful, extreme, or outrageous speech. As such, was it okay for Ravi and Wei to stream video of Ravis gay roommate, Tyler Clementi, engaging in homosexual activity across the Internet? 101 Would Clementis estate not have a claim for IIED had Ravi and Wei given notice of their intent to stream the video? 102 In Snyder, Justice Alito correctly noted the severity of the verbal attack Westboro waged against Snyder. 103 Certainly, Westboros conduct was extreme and outrageous, and specifically attacked Snyder because he was Catholic and a member of the military. 104 Correctly recognizing both Matthew and his father were not public figures, Justice Alito reiterated

100. Id. 101. Lisa W. Foderaro, Private Moment Made Public, Then a Fatal Jump, N.Y. TIMES, Sept. 30, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/30/nyregion/30suicide.html?_r=1. 102. See, e.g., John G. Culhane, More than the Victims: A Population-Based, Public Health Approach to Bullying of LGBT Youth, 38 RUTGERS L. REC. 1 (2010-2011) (Tyler Clementi is dead because the internet dissemination of videos showing him in an intimate setting with another man was too much for him to bear. He jumped off the George Washington Bridge.) (citation omitted). 103. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1225-26 (Alito, J. dissenting). After Lance Cpl. Matthew Snyders funeral, the Westboro Church posted an online account directly attacking Petitioner Snyder: God blessed you, Mr. and Mrs. Snyder, with a resource and his name was Matthew. He was an arrow in your quiver! In thanks to God for the comfort the child could bring you, you had a DUTY to prepare that child to serve the LORD his GOD-PERIOD! You did JUST THE OPPOSITEyou raised him for the devil. .... Albert and Julie RIPPED that body apart and taught Matthew to defy his Creator, to divorce, and to commit adultery. They taught him how to support the largest pedophile machine in the history of the entire world, the Roman Catholic monstrosity. Every dime they gave the Roman Catholic monster they condemned their own souls. They also, in supporting satanic Catholicism, taught Matthew to be an idolater. .... Then after all that they sent him to fight for the United States of Sodom, a filthy country that is in lock step with his evil, wicked, and sinful manner of life, putting him in the cross hairs of a God that is so mad He has smoke coming from his nostrils and fire from his mouth! How dumb was that? Id. at 1226 (alterations in original) (internal citations omitted). 104. Id.

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

491

the attack was not speech on a matter of public concern. 105 Justice Alito also recognized Westboros publicity-seeking motivation [did not] soften the sting of their attack. And as far as culpability is concerned, one might well think that wounding statements uttered in the heat of a private feud are less, not more, blameworthy than similar statements made as part of a cold and calculated strategy to slash a stranger as a means of attracting public attention. 106 In Tyler Clementis case, Ravi and Wei clearly strategized and calculated the streaming of the video, Ravi set up the camera and used Weis computer to send the video out over the Internet, and doing so added little to the public debate regarding homosexuals. 107 Moreover, in applying the majoritys rationale in Snyder, the Clementi video stream appears analogous to the non-public speech in San Diego v. Roe. 108 However, because neither Clementi, nor his bullies, were public employees, Clementis potential claim for IIED may experience a similar fate as the father of a deceased marine wishing to bury his son in peace. Despite the boundaries of the public concern test . . . not [being] well defined, 109 the Supreme Court appears willing to deny First Amendment protectionthereby protecting the victimwhen the speech at issue does not touch on a matter of public concern 110 or when the extreme or outrageous speech is disseminated to a few individuals, sworn to secrecy. 111 However, all these limitations amount to is that a wellcrafted, harmful, extreme, or outrageous message, directed at a broad audience, will receive protection under the First Amendment and will thus be insulated from liability for its effects.

105. Id. 106. Id. at 1227 107. John Lederman, Dharum Ravi Wants Tyler Clementi Case Dismissed, HUFFINGTON POST, July 25, 2011, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/07/26/dharunravi-wants-tyler-c_n_909451.html. 108. 543 U.S. 77, 84 (2004) (holding police officer speech was entitled to First Amendment protection due to the speech not relating to the mission of his employer nor referencing a matter of public concern). 109. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1216 (quoting San Diego, 543 U.S. at 83). 110. San Diego, 543 U.S. at 82-83 (applying the Pickering public concern test for government employees). 111. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1216 (citing Dun & Bradstreet, Inc. v. Greenmoss Builders, Inc., 472 U.S. 749, 762 (1985) for the proposition that speech solely in the individual interest of the speaker and its specific business audience . . . concerns no public issue confirmed by the fact that the particular report was sent to only five subscribers to the reporting service, who were bound not to disseminate it further.) (alterations in original).

492

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

Moreover, did the fact that Westboro picketed on a public street somehow make the extreme and outrageous conduct subject to First Amendment protection? According to the majority, and many scholars, 112 extreme or outrageous speech occurring at a public place on a matter of public concern, . . . is entitled to special protection under the First Amendment. Such speech cannot be restricted simply because it is upsetting or arouses contempt. 113 In contrast, Justice Alito stated [t]he Court suggests the wounds inflicted by vicious verbal assaults at funerals will be prevented or at least mitigated in the future by new laws that restrict picketing within a specified distance of a funeral . . . however, . . . the enactment of these laws is no substitute for the protection provided by the established IIED tort . . . [t]he verbal attacks that severely wounded petitioner in this case complied with the new Maryland law regulating funeral picketing. 114 Yet, there is absolutely nothing to suggest that Congress and the state legislatures, in enacting these laws, intended them to displace the protection provided by the well-established IIED tort. 115 At the conclusion of his dissent, Justice Alito mentions the majoritys use of Hustler Magazine v. Falwell 116 as failing to support the broad proposition adopted by the Court of Appeals in Snyder. 117 Justice Alito points out that while Hustler Magazine involved a claim for IIED, the plaintiff was a public figure and the holding was limited to publications like Hustler magazine. 118 Justice Alito distinguished the

112. See, e.g., Eugene Volokh, Freedom of Speech and the Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress Tort, 2010 CARDOZO L. REV. DE NOVO 300 (2010). See also Brownstein & Amar, supra note 9, at 44 (Assume a speaker strongly dislikes one of his colleagues at work. The speaker stands of a soapbox in a public park, and states that his colleague is a horrible person who should be despised by G-d and sent to hell when he dies.). In proposing the following constitutionally protected hypothetical, Professor Brownstein and Professor Amar assert mean-spirited private speech, [which] isnt defamatory, . . . is constitutionally protectedat least if it is addressed to a public audience and expressed in a location some distance away from the place where the maligned colleagues lives and works. Id. 113. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1219. 114. Id. (Alito, J. dissenting). 115. Id. at 1227. 116. 485 U.S. 46 (1988) (holding that the First Amendment prevents a public figure from sustaining a viable suit for IIED damages). 117. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1228 (Alito, J. dissenting). 118. Id. (Alito, J. dissenting) (Unless a caricature of a public figure can reasonably be interpreted as stating facts that may be proved to be wrong, the caricature does not have the same potential to wound as a personal verbal assault on a vulnerable private figure.).

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

493

caricature in Hustler Magazine as not hav[ing] the same potential to wound as a personal verbal assault on a vulnerable private figure. 119 Surely there is no greater wound from a personal attack than the tragic result in Tyler Clementis case. 120 B. The Constitutional Bully The Supreme Courts holding in Snyder essentially gives the bully a free pass so long as the bullys extreme and outrageous conduct both occurs in a public place where the bully is lawfully entitled to be, 121 and the conduct relates to broad issues of interest to society at large, rather than matters of purely private concern. 122 Using the First Amendment as a shield, a bully can become the all-powerful constitutional bully by merely following the High Courts precedent set forth in Snyder. First, the constitutional bully may choose a victim that is not a public figure. Since the Supreme Court seems unwilling to provide these individuals protection from any extreme or outrageous conduct, the bully may wish to inflict distress upon this individual. However, if the bully has a yearning to lash out at a public figure, the constitutional bully need not invoke the shield of the First Amendment, as these individuals have consented to the verbal assaults of another individual. 123 Second, providing the victim notice, directly or indirectly, of the constitutional bullys intention to invoke the harmful conduct ensures that the victim is aware of what is to come. The victim has the ability to avoid the constitutional bully to the detriment of the victims freedom to pursue life free from intentional, extreme, and outrageous speech. 124 Then, the

119. Id. 120. See Culhane, supra note 102 and accompanying text. 121. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1218-19. 122. Id. at 1217. (quoting Dun & Bradstreet, 472 U.S. at 759). 123. Gertz v. Welch, 418 U.S. 323, 342 (1974) (Those who, by reason of the notoriety of their achievements or the vigor and success with which they seek the publics attention, are properly classed as public figures and those who hold governmental office may recover for injury to reputation only on clear and convincing proof that the defamatory falsehood was made with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard for the truth.); see also W. Wat Hopkins, Snyder v. Phelps, Private Persons & Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress: A Chance for the Supreme Court to Set Things Right, 9 FIRST AMEND. L. REV. 149, 163 (2010) (arguing that Gertz provided a degree of protection for private persons who are attacked without voluntarily entering what has been called the rough and tumble of the American ideological marketplace and unwittingly become targets.) (citation omitted). 124. After learning of Westboros decision to picket his sons funeral, should Petitioner Snyder have altered his plan of burying his son that day, at that location, or even worse, forgone burying his son in any public place? Despite the funeral procession route being altered, Westboro was still able to inflict emotional harm by the intentional,

494

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 57: 473

constitutional bully can ensure the extreme and outrageous conduct directed toward the victim is couched in some matter of public concern and can calculate the message to reach as broad a public audience as possible. 125 Next, the constitutional bully can craft the conduct and messages directed toward the victim in general phrases that avoid proper names or references directly to the victim. However, if the victim is a public figure, the constitutional bully is free to use the individuals name, likeness, or anything else. 126 Then, the constitutional bully need only place his or her soap box at a strategic location and convey the message from a place where the bully has the legal right to be. 127 While the foregoing analysis presents a troubling result, all hope and protection may not be completely lost for the victims of the constitutional bully. If there is a pre-existing relationship or conflict between [the bully] and [the victim] that might suggest [the bully]s speech on public matters was intended to mask an attack on [the victim] over a private matter, 128 redress for the victim under a claim for IIED may not be completely shielded. If the bully does not have a lawful right to be in the place from which the extreme or outrageous speech occurs, the victims claim for IIED may gain the force necessary to pierce the constitutional bullys purported First Amendment shield. 129 VI. CONCLUSION If the Supreme Court has determined sticks and stones may break the bones of a victim, but the equally effective and harmful words never harm him, what can the victim of the bullying do? Will bullied victims be forced to meet violence with violence and disregard the accepted norms of civil society? Moreover, should the government control the

extreme, and outrageous speech. Thus, it appears, Mr. Snyder should have turned the other cheek and avoided the plan of burying his son in the manner he desired to give way to Westboros right to express their dismay with the current state of the Union. 125. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1217. 126. See Hustler, 485 U.S. at 56 (holding public figures are unable to recover damages from a publishers advertisement depicting plaintiff in a sexual parody under a state law claim for IIED). 127. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1218 (Simply put, the [bullies] had the right to be where they were.). 128. Id. at 1217-18. 129. See Brownstein & Amar, supra note 9, at 45 (noting that in Snyder, the Court did not answer the question of what if the church members were standing in a place where they did not have a right to be?).

2011]

AFTERMATH OF SNYDER V. PHELPS

495

means by which a bully, most notably a cyberbully, 130 delivers his or her extreme or outrageous words? 131 Pure government regulation of speech certainly amounts to the chilling effect on free speech our forefathers feared most. 132 Unfortunately for the victims of bullying, the Supreme Court appears only willing to remove the sticks and stones from the bullys arsenal, while leaving the sharpest weapons of allthe words intact. As Justice Alito stated at the conclusion of his dissenting opinion, [i]n order to have a society in which public issues can be openly and vigorously debated, it is not necessary to allow the brutalization of innocent victims. 133 Moreover, [w]hen grave injury is intentionally inflicted by means of an attack . . . the First Amendment should not interfere with recovery. 134 Unfortunately for the victims of bullies like the members of the Westboro Church and Molly Wei, 135 the victim must beware: sticks and stones may break ones bones, thereby imposing liability on the bullies for the intentional conduct; however, extreme and outrageous words resulting in emotional harm will not enable recovery under IIED.

130. Cyberbullying is defined as the willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices. Sameer Hinduja & Justin W. Patchin, Cyberbullying Identification, Prevention, and Response, CYBERBULLYING RES. CTR. (2010), http://www.cyberbullying.us/Cyberbullying_Identification_Prevention_Response_Fact_S heet.pdf (last visited Mar. 4, 2012). 131. See Clay Dillow, Former CIA Chief: A Separate Internet Could Curb Cyber Threats, POPSCI.COM (July 7, 2011, 1:54 PM), available at http://www.popsci.com/technology/article/2011-07/former-cia-chief-dot-secure-domaincould-curb-cyber-threats. 132. Brown v. Entmt Merch. Assn, 131 S. Ct. 2729, 2743 (2011) (While perfect clarity and precise guidance have never been required even of regulations that restrict expressive activity, government may regulate in the area of First Amendment freedoms only with narrow specificity[.]) (citations omitted) (internal quotation marks omitted). 133. Snyder, 131 S. Ct. at 1229 (Alito, J. dissenting) (emphasis added). 134. Id. at 1223 (Alito, J. dissenting). 135. Aman Ali, Defense: Rutgers Roommate Never Bullied Gay Man Before Suicide, U.S. NEWSREUTERS.COM (July 25, 2011, 12:59 PM), http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/07/25/us-rutgers-suicideidUSTRE76O4B420110725. Under the terms of her plea deal, all charges against Molly Wei will be dismissed in exchange for her testimony against Ravi, her successful completion of 300 community service hours, cyberbullying counseling, and further education on alternative lifestyles. Id. Unfortunately, this all appears to be a nominal price to pay in comparison to the outcome of Clementis cyberbullicide. See Hinduja & Patchin, supra note 130 (defining cyberbullicide as suicide indirectly or directly influenced by experiences with online aggression).

You might also like

- Qian FINALDocument57 pagesQian FINALWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Masterson FINALDocument38 pagesMasterson FINALWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Kan FINALDocument74 pagesKan FINALWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Jaffe FINALDocument27 pagesJaffe FINALWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Huffman FinalDocument17 pagesHuffman FinalWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Restricting LLC Hide-And-Seek: Reverse Piercing The Corporate Veil in The State of MichiganDocument27 pagesRestricting LLC Hide-And-Seek: Reverse Piercing The Corporate Veil in The State of MichiganWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Client Liability For An Attorney'S Torts: An Evolving Problem That Warrants A Modern SolutionDocument21 pagesClient Liability For An Attorney'S Torts: An Evolving Problem That Warrants A Modern SolutionWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Trivax - FinalDocument27 pagesTrivax - FinalWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Gandhi FinalDocument24 pagesGandhi FinalWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Dupes FinalDocument22 pagesDupes FinalWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Field Hearings and Congressional OversightDocument22 pagesField Hearings and Congressional OversightWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Breitfeld FinalDocument33 pagesBreitfeld FinalWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Review of EEOC Pre-Suit Requirements Post-Mach MiningDocument17 pagesReview of EEOC Pre-Suit Requirements Post-Mach MiningWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Doster FinalDocument14 pagesDoster FinalWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Defining Congressional Oversight and Measuring Its EffectivenessDocument22 pagesDefining Congressional Oversight and Measuring Its EffectivenessWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Extraterritorial Congressional OversightDocument21 pagesExtraterritorial Congressional OversightWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- The Atrophying of The Congressional Research Service's Role in Supporting Committee OversightDocument14 pagesThe Atrophying of The Congressional Research Service's Role in Supporting Committee OversightWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- The State of Trademark Law Following B&B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Industries, Inc.: Not As Groundbreaking As It May AppearDocument19 pagesThe State of Trademark Law Following B&B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Industries, Inc.: Not As Groundbreaking As It May AppearWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Delegation and Its DiscontentsDocument42 pagesDelegation and Its DiscontentsWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Divine Disputes: Why and How Michigan Courts Should Revisit Church Property LawDocument27 pagesDivine Disputes: Why and How Michigan Courts Should Revisit Church Property LawWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Executive Privilege in A Hyper-Partisan EraDocument31 pagesExecutive Privilege in A Hyper-Partisan EraWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Who Conducts Oversight? Bill-Writers, Lifers, and NailbitersDocument22 pagesWho Conducts Oversight? Bill-Writers, Lifers, and NailbitersWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- EvidenceDocument68 pagesEvidenceWayneLawReviewNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Pangan vs. PererrasDocument2 pagesPangan vs. PererrasJoicey CatamioNo ratings yet

- Sample Dacion en PagoDocument8 pagesSample Dacion en PagoTibs100% (2)

- Padura v. BaldovinoDocument4 pagesPadura v. BaldovinoJustin MoretoNo ratings yet

- Oblicon (Prescription)Document25 pagesOblicon (Prescription)Ange Buenaventura Salazar100% (1)

- Terrance James-Bey v. State of North Carolina, 4th Cir. (2012)Document3 pagesTerrance James-Bey v. State of North Carolina, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- GIA ConstitutionDocument12 pagesGIA ConstitutionRas Anansa0% (1)

- Jeffrey Isaacs v. Dartmouth CollegeDocument58 pagesJeffrey Isaacs v. Dartmouth CollegeJeffreyIsaacsNo ratings yet

- Pemberton Township OPRA Request FormDocument2 pagesPemberton Township OPRA Request FormThe Citizens CampaignNo ratings yet

- V-1 G.R. No. 169292 Spouses Francisco de Guzman, Jr. and Amparo O. de Guzman, Petitioners, vs. Cesar Ochoa and Sylvia A. Ochoa April 2011Document3 pagesV-1 G.R. No. 169292 Spouses Francisco de Guzman, Jr. and Amparo O. de Guzman, Petitioners, vs. Cesar Ochoa and Sylvia A. Ochoa April 2011Iter MercatabantNo ratings yet

- Patent General Principles: Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 113388, September 5, 1997)Document41 pagesPatent General Principles: Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 113388, September 5, 1997)kunta kinteNo ratings yet

- Ja Ina GalesDocument7 pagesJa Ina GalesRhows BuergoNo ratings yet

- Bjective: 1. Practicing As An Advocate Under The Supervision of SeniorDocument4 pagesBjective: 1. Practicing As An Advocate Under The Supervision of Seniornikhil rajpurohitNo ratings yet

- Option Purchase Agreement - EngDocument7 pagesOption Purchase Agreement - EngmasterfoxNo ratings yet

- Partnership ActDocument30 pagesPartnership ActRaselAhmedNo ratings yet

- Spec Pro Digest by ACC PDFDocument177 pagesSpec Pro Digest by ACC PDFHarry Potter100% (1)

- PEDRO T. ACOSTA, Plaintiff-Appellant, vs. DAVID FLOR, Defendant-AppelleeDocument32 pagesPEDRO T. ACOSTA, Plaintiff-Appellant, vs. DAVID FLOR, Defendant-AppelleeBernice RosarioNo ratings yet

- CLAT BrochureDocument52 pagesCLAT Brochuresundar06No ratings yet

- The Indian Contract Act, 1872Document20 pagesThe Indian Contract Act, 1872spark_123100% (14)

- Cole v. United States Postal Service Et Al - Document No. 3Document3 pagesCole v. United States Postal Service Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Padilla vs. URC Digest PDFDocument1 pagePadilla vs. URC Digest PDFlouise_canlas_1No ratings yet

- Heirs of Poe V Malayan Case DigestDocument4 pagesHeirs of Poe V Malayan Case DigestthemarkroxasNo ratings yet

- Induction Training Programme For The Newly Appointed Civil Judges Class IIDocument28 pagesInduction Training Programme For The Newly Appointed Civil Judges Class IINarang AdityaNo ratings yet

- Petitioner, vs. Metropolitan RespondentsDocument1 pagePetitioner, vs. Metropolitan RespondentsChanel GarciaNo ratings yet

- 1) Cebu Portland Cement v. CTA, L-29059, 15 Dec 1987, 156 SCRA 535 (Lifeblood of The Government)Document9 pages1) Cebu Portland Cement v. CTA, L-29059, 15 Dec 1987, 156 SCRA 535 (Lifeblood of The Government)Guiller C. MagsumbolNo ratings yet

- Magdalena Estate VsDocument22 pagesMagdalena Estate VsAsh CampiaoNo ratings yet

- Notice 5536 29 Jan 2022Document356 pagesNotice 5536 29 Jan 2022Dany georgeNo ratings yet

- Philippine Rabbit Bus Lines V IACDocument2 pagesPhilippine Rabbit Bus Lines V IACHoven Macasinag100% (2)

- Documents - The New Ostpolitik and German-German Relations: Permanent LegationsDocument5 pagesDocuments - The New Ostpolitik and German-German Relations: Permanent LegationsKhairun Nisa JNo ratings yet

- State Court of Appeals December 15 2020 OrderDocument19 pagesState Court of Appeals December 15 2020 OrderJohanna Ferebee StillNo ratings yet

- China'S Judicial System: People'S Courts, Procuratorates, and Public SecurityDocument8 pagesChina'S Judicial System: People'S Courts, Procuratorates, and Public SecurityDrJoyjit HazarikaNo ratings yet