Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bacon Remaking The Body

Uploaded by

Erick FloresOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bacon Remaking The Body

Uploaded by

Erick FloresCopyright:

Available Formats

JOURNAL FOR CULTURAL RESEARCH

VOLUME 13

NUMBER 2

(APRIL 2009)

Remaking the Body: The Cultural Dimensions of Francis Bacon

Rina Arya

rinaarya77@yahoo.co.uk; RinaArya Francis 0 2000002009 13 2009 Originalfor Francis 1479-7585 Cultural Research Journal&Article 10.1080/14797580902829752 RCUV_A_383145.sgm r.arya@chester.ac.uk Taylor and (print)/1740-1666 (online)

In 2008 the Tate Gallery hosted a retrospective of Francis Bacon to commemorate his centenary. This occasion was one of the motivations for presenting this reflection on Bacon and his legacy 16 years after his death. The exhibition demonstrated Bacons technical ability to capture the nuances of flesh in a remarkably visceral way and consolidated his position as one of the greatest painters of the human body. In this article I want to concentrate on the cultural dimensions of Bacons Weltanschauung. I argue that it is not a misrepresentation to discuss Bacon as a social and cultural commentator but rather a way of intensifying his aestheticism.

Introduction

In 2008 the Tate Gallery hosted a retrospective of Francis Bacon to commemorate his centenary. This occasion was one of the motivations for presenting this reflection on Bacon and his legacy 16 years after his death. The exhibition demonstrated Bacons technical ability to capture the nuances of flesh in a remarkably visceral way and consolidated his position as one of the greatest painters of the human body. In this article I want to concentrate on the cultural dimensions of Bacons Weltanschauung. I argue that it is not a misrepresentation to discuss Bacon as a social and cultural commentator but rather a way of intensifying his aestheticism. This was the source of the curators motivations for the 2008 retrospective at the Tate. They believed that Bacon was not only one of the great painters of the human form but one of the great articulators of the human condition (Gale & Stephens 2008, p. 27).

ISSN 14797585 print/17401666 online/09/02014316 2009 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/14797580902829752

144

ARYA

Clearing Away the Veils that we Live Behind1

I propose that the sustained interest in Bacon by the critics and public alike can partially be attributed to the epistemological questions that his paintings posed to an audience that had lived through the horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust. Bacon was keen to emphasize his contemporaneity in both his sensibility and outlook. At times he made contradictory remarks about the purpose and role attributed to painting. For example, he remarked on a number of occasions that he painted for himself and did not have a message to impart. This rather insular outlook was at other times counteracted by a greater awareness of the power of painting to move and shape cultural perspectives. In this second outlook Bacon showed a strong awareness of the cultural currents of thought within politics and other domains. He was influenced by a number of different media by painting, photography, film, literature and poetry and eagerly assimilated these influences. The influence of the films of Eisenstein, the photographs of Muybridge, the narratives of Greek mythology, and modernist literary works can all be seen in his work. I am inclined to describe Bacon as being an exceptional social commentator who recorded human behaviour, articulating it in his own idiosyncratic style. He once described himself as a pulverizing machine (Russell 1993, p. 71) and this is an apt metaphor for his predilection to strip the human being down to its bare essentials of flesh and blood. When we examine his work, we are then led to his view of the world, which is simultaneously exhilarating and also despairing. Bacon invested art with the power to communicate truths about the age that one lives in. He asked: Why, after the great artists, do people ever try to do anything again? Only because, from generation to generation, through what the great artists have done, the instincts change (Sylvester 1993, p. 59). In an interview with Davies, Bacon observes that great art is always a way of concentrating, reinventing what is called fact, what we know of our existence a reconcentration tearing away the veils (Davies & Yard 1986, p. 110). Art then becomes a process of updating perspectives that resonate with the people of the time. Bacons subsequent updating of Velzquezs painting of Pope Innocent X (1650) is seen in his papal series but most notably pinpointed in the Study after Velzquezs Portrait of Innocent X (1953). Although Bacons version has clearly been derived from Velzquezs representation, the rendition of the Pope and the tone of the piece could not be more different. Velzquez painted the Pope at the height of the Counter-Reformation when papal power was at its greatest and the Pope was treated with reverence. His poised, authoritative and inscrutable gaze conveys his role ex cathedra. In sharp contrast is Bacons inarticulate wretch of a Pope who evokes fallibility and fear. These two alternative viewpoints are pertinent in their respective contexts. In his depiction of papal glory Velzquez was adhering to convention. However, in Bacons experience of living

1. This phrase is taken from Bacons statements about his aims, which he spoke about in his extensive interviews with David Sylvester. See Sylvester 1993, p. 82.

REMAKING THE BODY

145

through the Irish Civil War (where as a Protestant he represented the minority) the Pope represented conflict and stood as the figure of opposition. In Bacons depiction the Popes power is undermined by the scream, which shatters any claim to authority. The scream of the Pope then subsequently invalidates the accompanying symbols of authority within the painting, such as the papal robes and other articles. Davies stresses the tragicomic aspects of the painting: the papal robes that have a powerful symbolic significance are transformed in the Bacon painting to become some form of ludicrous fancy dress in a Genet play (Davies 1978, 100). Zweite argues that rather than viewing Bacons study as a negation of Velzquezs representation of the Pope, it was an intensification and historical relocation (Zweite 2006a, p. 72). I think that rather than focusing on how Bacons Pope differs from Velzquezs, it is better to evaluate Bacons motivations more broadly. By referencing the strong tradition of papal painting within the history of art and then presenting an interpretation, which at the outset looks like a defacement of centuries of the Grand Style, Bacons depiction is iconoclastic. Another claim that Bacon held was that we live a screened or veiled existence, and that one of the purposes of art should be about removing these screens and veils with a view to uncover the truth about existence (what Bacon referred to as the brutality of fact).2 The truth about existence concerns certain facts about existence that are normally suppressed in aesthetic representation. The facts that Bacon delineates in his oeuvre are the role of the human in a Godless world and the doubt this places on questions of purpose and identity. Bacon aimed for rawness and directness (Sylvester 1993, p. 48). In the process of painting Bacon describes the struggle between keeping the form open and trapping the fact, and the moment that truth emerges through the interlocking of paint and idea. This moment corresponds to the direct realism that Bacon wished to emulate. I argue that the uniqueness of Bacons art lies in his depiction of the human body. He strips away the layers of the body until we get to the flesh and blood reality. He seeks what is universal to all human beings and eliminates any extraneous material. Whatever the setting (an anonymous empty space, a stage or circus arena, a staircase, a broom cupboard), Bacons figures are seen sub specie aeternitatis (Schmied 2006, p. 96). In this process of reconstructing the body, Bacon poses interesting cross-disciplinary questions, which engage with sociology, anthropology, and theology amongst other disciplines. Bacon remakes the body in a strategic way. He exposes the limitations of the representation of the static body and of mere appearance (which is defined as likeness) and then embarks on a practice of distortion, whereby the body is disfigured. In the process of distorting the body Bacon takes the viewer beyond the appearance and into the realms that Leiris defines as a heightened sensation of presence (Leiris 1983, p. 27). In this trajectory Bacon enacts a shift from

2. The brutality of fact was a phrase that Bacon has become renowned for saying. It was subsequently used as the title of a television film about his life and also in the third edition of the interviews with Sylvester.

146

ARYA

the depiction of a body that is frozen in appearance and fixed in time to a representation that captures temporality and change, what I describe as the natural body. He depicts the natural body with recourse to smudged contours and blurred boundaries the body is in a state of liquefaction. Every twist and turn of the body is rendered in line and tone, which is reflected in the misshapen form and bruised colouration. These factors create the impression that his figures are in the throes of mental and physical anguish. They are not in repose and are preoccupied with their mortality. According to Bacon, death is not a state that exists after life but is inherent within its very condition (Sylvester 1993, p. 78). The pained appearances of the contorted bodies and facial expressions (which include in their range grimaces, cries and screams) articulate a sense of the bodily. We do not simply see the body but experience sensations that evoke a sense of embodiment. We move from inner to outer. This move coheres with Bacons desire to depict a natural body. In Bacons Godless world pain and suffering are not teleological and the shadow of death exists in every turn of the body. Visually, this is seen in the palpable shadows of the body that often have greater opacity than the body itself, and the abyssal black spaces into which the figure dissolves. In his remaking of the body Bacon reframes the dialogue between hitherto polarized states, such as life and death, wholeness and fragmentation, and the sacred and the profane.

Remaking the Body: The Art of Distortion

Bacons main subject matter is the human body. This subject is subdivided into categories, such as portraits of friends and lovers, portraits of anonymous figures in interiors, portraits of popes, and general studies of the human body (which include his depictions of crucifixions). All these depictions have in common the insistence on the corporeality of the body where the figure(s) displays an awareness of the inevitability of death. Bacon criticizes the tradition within representational painting that depicts the body in stasis, such as is found in the history of portrait painting. Hunter observes Bacons Bergsonian horror of the static and his desire to move painting closer to the optical and psychological sources of movement and action in life (Tinterow 2008, p. 32). According to Bacon the lived body is in a continual state of motion, where motion can be conceived of as voluntary (such as walking) or involuntary (such as in spasmodic reflexes as sneezing or internal physiological processes, like the heartbeat). Bacon is not explicit about the particularities of these processes. In The Logic of Sensation, Deleuze describes the bodily processes that occur in Bacons bodies in terms of disequilibrium, where the hiccup or the act of vomiting can be seen as ways in which the body wishes to escape itself through the orifice of the mouth (Deleuze 2003, p. 15).3 The constant sense of motion means that the inner functions and outer surface are in a state of perpetual disruption.

3. According to Deleuze this desire to escape the body is both literal and metaphorical.

REMAKING THE BODY

147

Bacon discusses the motion of the body with reference to pulsations or emanations the energy that a person gives off. He discusses how his idea of a person transcends the physical description of what the person looks like, that is, their appearance, and is instead tied up with a whole host of non-material aspects that are inextricably linked to the living quality (Sylvester 1993, p. 174). And it is this appearance plus living quality that he aspires to convey in his painting. He states how:

There is the appearance and there is the energy within the appearance. And that is an extremely difficult thing to trap. Of course, a persons appearance is closely linked with their energy. So that, when you are in the street and in the distance you see somebody you know, you can tell who they are just by the way they walk and by the way they move. But I dont know whether it would be possible to do a portrait of somebody just by making a gesture of them. So far it seems that if you are doing a portrait you have to record the face. But with their face you have to try and trap the energy that emanates from them. (Sylvester 1993, p. 175)

From the above commentary it can be inferred that appearance can be equated with the static representation, whilst the living quality is appearance plus the non-material aspects of energy that resist stasis. In his explorations of the natural body Bacon deformed the single viewpoint, which is seen in the distortions of the body. He often smeared and smudged lines to achieve this, such as evidenced in Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne (1966) and Study for Three Heads (1962). In his attempt to present naturalism he went beyond verisimilitude, the appearance of being true or real to the actual truth of the living person as a corporeal entity and not as a two-dimensional representation.4 Aesthetically, he was able to implement this in his experimental technique, which in his own words was a tightrope walk between figuration and abstraction (Sylvester 1993, p. 12). Bone and flesh are in a continual state of tension and every turn (motion) of the flesh results in distortion, which appears to be a relationship of tension or torsion between the bone structure and the flesh. The brutal fact that I spoke of earlier is the ability to be able to render the person as they really look in life and not simply a photographic and static representation. The Western tradition of the history of art is predicated on the JudaeoChristian legacy. One fundamental tenet is the Imago dei (in Gods image). This refers to the belief that the human was made in the image of God, where God represents the ground of being. Paintings such as Velzquezs Pope Innocent X and Titians Portrait of Pope Paul III (1543) reflect the importance of this ideology. These depictions are rendered with the intention of memorializing and eternalizing the Popes. The Pope as the divine representative of Christ on Earth is sacrosanct. This is reflected in the representations that sought to capture the holiness and reverence of the Pope. Gods representation was taken to be problematic. From early Christian and Byzantine art right through to the

4. The obvious contradiction and paradox that cannot be ignored here is that Bacon is still representing lived reality on a two-dimensional surface, which is inescapably a representation and not the real. However, taking heed of the paradox, his process deserves commendation.

148

ARYA

nineteenth century, all religious art echoed this ground of being. This tradition extended to non-religious but very important subjects, such as royalty. The visual representations of these figures were mimetic, and strove to imitate the ultimate representation. In the Byzantine era religious figures (icons) were regarded as a focus for devotion. The death of God was heralded in the nineteenth century and by the twentieth century was widely held amongst progressive thinkers. The death of God removed this absolute ground of being. If God signifies absolute values of truth, beauty, and goodness, then the death of God removes teleological justifications of suffering and theological conceits of life after death. Bacons depiction of the natural body, which defies stasis and fixity, is viewed from within this context. Bacons remaking of the body is a simultaneous deconstruction of an established tradition of aesthetic representation. Bacon transcends the depiction of the appearance of the human body to articulate the experience of embodiment, which invariably means an experience of death.

Levels of Violence

Bacons figures often look as if they have been embroiled in a violent struggle and have undergone horrific torture. Bacon lived through violent times and his early years were turbulent. He grew up during the Irish Civil War and the Second World War. As a young child Bacon experienced the effects of violence, which he reported to his interviewers and biographers. These incidents remained vivid in his psyche but should not be regarded as literally present in his work. Bacon himself made a distinction between the violence in his life, the violence that he lived amidst and the violence in painting (Sylvester 1993, p. 81). He states how, when talking about the violence of paint, its nothing to do with the violence of war (Sylvester 1993, p. 81). Ades develops this distinction by describing the literal violence as mirrored violence, which stands apart from the violence that arose from the suggestion in his paint. The violence he is talking about does not have anything to do with the violent application of paint, with expressionist violence (Ades 1985, p. 8). It is not about the outpouring of emotion or the psychological suggestion of pain as was the case with the German Expressionist painters of the 1920s. Nor is it about the outpouring of sensation akin to the work of the Abstract Expressionists of the 1940s. Bacons violence comes out of an ability to transform the multitude of sensations surrounding an image into paint. Deleuze qualifies this: Bacon, to be sure, often traffics in the violence of a depicted scene: spectacles of horror, crucifixions, prostheses and mutilations, monsters. But these are overly facile detours, detours that the artist judges severely and condemns in his work (Deleuze 2003, p. x). The violence in Bacon is not issued from an external source but rather occurs from within: these are invisible forces that deform the flesh (Deleuze 2003, p. x). These invisible forces include any spasmodic activity which causes disequilibrium within the body, such as the violence of a hiccup (Deleuze 2003, p. x) or a sneeze. What

REMAKING THE BODY

149

is crucial is that there is no external source of horror that causes the deformation of flesh. In Study after Velsquezs Portrait of Innocent X the deformation takes the form of the scream on the face of the Pope. However, Deleuze asserts that the Pope is not screaming at anything and there is no object that causes the scream. I want to add the violence of viewing to this typology. This is the starting point of Van Alphens study of Bacon in Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self (1992). He describes the effect of viewing Bacon:

Seeing a work by Francis Bacon hurts. It causes pain. The first time I saw a painting by Bacon, I was literally left speechless. I was touched so profoundly because the experience was one of total engagement, of being dragged along by the work. (Van Alphen 1992, p. 9)

This wounding experience causes a silence about that feeling of paralysis (Van Alphen 1992, p. 9). The corporeal turbulence of Bacons figures is mirrored and transferred to viewers so that we experience a sense of wounding. His art affects the viewer on both a visceral and an intellectual level, in that order. The work grips the viewers senses and this feeling is then processed intellectually. One of the reasons why his depictions instill such feelings of trepidation and violence in the viewer is because of the anti-narrative strategies that he implements which inhibit cursory reflection. Bacon did not want his figures to be viewed within narrative confines because he felt that narratives deflect the focus from the figure and onto the story itself, which in turn reduces its impact. And so he disrupts our sense of familiarity by not seeking recourse to anecdote or narrative structures. Many of his backdrops are stark and neutral, and can be compared to the anonymity of hotel rooms. He also employs the use of architectonic spaceframes to focus our gaze. The violence of viewing is demonstrated in Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), for example. A cursory glance at the title might lead one to believe that Bacon is depicting the three mourners or figures of sorrow at the foot of Bacons Cross. However, the actual title reads, at the base of a and not the Crucifixion. The use of the indefinite article, as Russell observes (1993, p. 11), transforms the meaning and intentions of the painting. This is not the Crucifixion and so we cannot sanction the brutality with reference to the Christian narrative. Furthermore, the absence of the Cross raises a question of focus: if we cant reflect on the physical cross, then where, and to what, do we draw our attention? One possibility is that the visual and narrative focal point is deflected onto the viewer. Bacon places the three figures at the eye level of the viewer because he is offering the viewer a reflection of him/herself. This is what we have become. Our natural reaction is to recoil from these menacing beasts and this sensation of recoil is heightened, if they are indeed us. By deflecting the focal point onto us Bacon is intimating that, in order to make sense of these creatures, we have to place ourselves at the centre of the interpretation of them. In his essay The Real Presence of Evil: Francis Bacons Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion Yates suggests that these figures represent the

150

ARYA

ones who crucify or who embody the emotions that feed the vengeance and cruelty of the act of crucifixion (Yates 1996, p. 24). Pursuing this point, Spender comments on how:

These appalling dehumanized faces, which epitomize cruelty and mockery are those of the crucifiers rather than the crucified His figures are those who participate in the crucifixion of humanity which includes themselves. If they are not always the people who actually hammer in the nails, they are those among the crowd which shares in the guilt of cruelty to the qualities that are or were beneficently human, and which here seem to have banished forever. (Yates 1996, p. 24)

We become the crucifiers. We cannot see the crucifixion because we are ensconced in the brutality of the action that goes into the act of putting to death. Therefore, in the context of Bacons image, the crucifixion is no longer a spectacle in the sense of something that we stand back and think about either contemplatively and/or sadistically. We are actually implicit in the making and complicit in the act itself. Viewing becomes performative. The only way to make sense of Bacons images is to enter into the narrative with them because there is no other narrative that occurs across the picture plane. And in this viewing we are torn apart and wounded. There is no salving, no making whole as happens in the Crucifixion of Christ, where the bodily fragments are rebound in the Resurrection. There is no resolution in Bacon, only the deepest confrontation of the horror of being. Bacon employs the symbol of the crucifixion anthropologically, as the behaviour between one man and another;5 and sociologically, as indicative of the prevalence of violence in society. Bacon is not literally depicting the actual violence that he encountered in his early years but he is applying his understanding of the ubiquity of violence in his figures. Violence reduces the human to the animal as we resort to instinctual responses. Ades discusses the interchangeability that occurs between the human and the animal in Bacons work as a zone of non-discrimination (Ades 1985, p. 14). By taking on the characteristics of an animal the human is able to release his/her pain more primally to scream louder and with a greater sense of abandonment. This animal element is a necessary part of the human psyche: without it he is restricted or constipated (Ades 1985, p. 15). This visual cross-over of the human and the animal is evidenced in a number of examples of Bacons figures, such as the three figures in Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), Figure Study II (19456), Head VI (1949), and Second Version of Triptych 1944 (1988). Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion was first exhibited at the Lefevre Gallery, London months before the end of the Second World War. When it was first put on public show the impact that it had was so monumental that the work of what were then better-known artists, such as Matthew Smith, Graham Sutherland, and Henry Moore was eclipsed by Bacons contribution. Critics

5. Sylvester 1993, p.23.

REMAKING THE BODY

151

unanimously agreed on the shock value this painting had on the British public (Alley 1993, p. 20). John Russell conveys the impact the painting had:

Common to all three figures was a mindless voracity, an automatic unregulated gluttony, a ravening undifferentiated capacity for hatred. Each was as if cornered, and only waiting for the chance to drag the observer down to its own level. They caused a [sic] total consternation. We had no name for them, and no name for what we felt about them. They were regarded as freaks, monsters irrelevant to the concerns of the day, and the product of an imagination so eccentric as not to count in any possible permanent way. They were spectres at what we all hoped was going to be a feast, and most people hoped that they would just be quietly put away. (Russell 1993, pp. 1011)

The unequivocal message that the painting conveyed was that nothing will ever be the same (Russell 1993, p. 11) and Bacon was launched into the art world. The impact the painting had was also related to its timeliness (or untimeliness, as many of his contemporaries may have viewed it). Unlike Moore or Sutherland, Bacon did not share the mood of war consolation and hence was unconcerned to direct his art at boosting public morale at the end of the Second World War. However, given the climate of spiritual malaise and general uncertainty that permeated aspects of British life, why did he feel inclined to produce such a horrific image? The mood in April 1945 in London was doleful. The bombing had ceased but its effects were widespread. Faced with blackouts and food rationing, many focused on the nostalgia of the great English past; a world which, Russell observed, no longer existed (Russell 1993, p. 9). Waughs Brideshead Revisited and Eliots Four Quartets were two popular texts, which in their different ways paid homage to the past. Another perspective focused on trying to instil a sense of peace and calm whilst looking to the future. Bacons art contravened both approaches. He remained firmly fixed on recent events and the atrocities and bloodshed. Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion can be regarded as a corrective of the romanticised outlook that many adopted. With Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion Bacon removed all the veils that people live behind and confronted viewers with the brutality of existence. The three grotesque figures ravening and aggressive, snarling, and snapping refused to give any respite to the viewer. In this image we are confronted with hell. They were the embodiment of carnage and evil, figures so distorted, so dispossessed. In his attempt to uncover the veils Bacon exposes the violence that lies at the heart of humanity in the guise of the three figures. Yates describes these forms as grotesque, where the grotesque refers to something that both is and is not of this world. The grotesque forms of Bacon are:

Forms rooted in our common world, enough so that we can see in them that which they distort, while in their otherness they suggest a different world

152

ARYA

altogether. They are part of our familiar world though transformed in images difficult to decipher, images that are foreign. (Yates 1997, p. 40) The three forms push us beneath the surface reality to a deeper level, which Bacon strove to capture in his articulation of humanity. Davies and Yard note Bacons tendencies to confront the grimmest realities of human existence in his crucifixions. They offer no hope or transcendence or image of meaningful suffering. (Yates 1997, p. 170)

Although allusions to the post-war climate have been made, the interpretation of the painting should be viewed more extensively to encompass not simply human behaviour during the war but the violence that lies at the heart of humanity. Bacon is alerting humanity to its own nature and disallows attempts to sanitize and banalize violence.

Existentialism in Bacon

Another theme that Bacon engaged with which started in the 1940s and continued throughout his life is the notion of identity and purpose. Given what some might regard as his misanthropic statement of humanity in Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, in the aftermath of the war Bacon develops this idea to its logical conclusion. Typically, in the Heads series of the 1940s and the Popes and the Men in Blue series of the 1950s, Bacon explores these questions. In these works man6 is left alone to ponder his existence. Featured in small interiors Bacon subjected all to this treatment: Rulers, top managers, demagogues on the one hand; prisoners, victims, the downtrodden on the other (Zweite 2006, p. 87). In their respective isolation booths these individuals are trapped in existential crisis, where their public images collapse and they experience psychological torture as they lose a sense of self. Bacons SelfPortrait (1973) conveys the individualism of the existentialist predicament. Resting on a sink, with only a lit light bulb above him, Bacon contemplates his fate. Contemporaneous with the production of these images were works of literary existentialism, such as Koestlers Darkness at Noon (1940), Camuss Ltranger (1942), and Sartres Huis Clos (1944). All these writers employ the metaphor of a claustrophobic, windowless space as indicative of the human predicament. Bacons isolated figures in windowless spaces are unprecedented in the history of portraiture. Traditionally in portraiture the sitter (the subject) displays awareness that they are being observed. This is portrayed in the self-conscious fashioning of the poses and postures. Even in more naturalized poses there is an implicit understanding that there are two presences in the painting, that of the sitter and that of the artist. Bacons candid-camera approach displays the sitter in the privacy of his/her own thoughts, oblivious to any external reference.

6. Bacon focused exclusively on male subjects in these works.

REMAKING THE BODY

153

Russell describes how Bacon is able to depict a psychological profile by portraying the sitter entirely on his own where they are able to explore the limits of selfhood without inhibition or restraint. The result is the collapse of self: we may feel that we are by turns all teeth, all eye, all ear, all nose (Russell 1993, p. 38). All the trappings of civilization and culture are stripped away and the human is shown in their natural state of vulnerability, in the proximity to the animal. These grotesque figures have been likened to Untermensch (Russell 1993, p. 38). Gale and Stephens summarize the existential predicament of the human: In a world without God, humans are no different to any other animal, subject to the same innate urges; transient and alone (Gale & Stephens 2008, p. 27). In his interviews and statements about his outlook Bacon was indisputably existentialist: I think of life as meaningless; but we give it meaning during our own existence. We create certain attitudes which give it a meaning while we exist, though they in themselves are meaningless, really (Sylvester 1993, p. 133). However, many do not have the resolution or depth to be able to contend with the lack of prescribed meaning and hence they fall into despair.

Refiguring the Polarities of Thought

In his remaking of the human body Bacon reconfigures states that are often conceived of as polar opposites: life and death, the sacred and the profane, wholeness and fragmentation, and form and formlessness. And in rethinking these putative binaries Bacon reworks them so that they are no longer binaries but are proximate. Death is then not conceived of as a state after life, but as a condition inherent within the living body. Bacon was particularly enamoured by Jean Cocteaus dictum, each day in the mirror I watch death at work (Sylvester 1993, p. 133). Life and death are inextricably interwoven so that the condition in which life is at its richest is also the moment of extreme dissolution (Zweite 2006b, p. 24). Gale and Stephens interpret Bacons desire to represent the body in motion as laden with (Barthesian) pathos because it draws our attention to the transience and fragility of human life (Gale & Stephens 2008, p. 20). This underpins Bacons representations and reframes how the viewer responds to mass distortion and fragmentation. The deformed bodies that are spilling out of their boundaries and that twist and turn about themselves (as in Figure in Movement 1978) demonstrate an intensified vitality. Deleuzes phrase ambulating flesh (Deleuze 1993, p. 24) astutely conveys this and also reconfigures the relationship between fragmentation and wholeness. The Baconian body does not adhere to conventions about bodily boundaries nor the concept that fragments make up the whole. It typically overflows into its surroundings and contains bodily boundaries that are permeable. However, each fragment of the Baconian body articulates such a strong sense of vitality and palpable presence (such as in Painting 1978) that it overrides any notion of incompleteness. Another duality that Bacon explores is the relationship between the sacred and the profane. Bacon takes religious symbols, such as the Pope and the Crucifixion,

154

ARYA

and profanizes them. With reference to Bacons screaming popes Zweite argues that the Holy Father opening his mouth in a scream is a degrading act which for all the aesthetic analysis still causes considerable disquiet (Zweite 2006a, p. 100). Similarly, he profanes the sacrality of the Crucifixion by conflating it with the butchers shop, which Sylvester observes: one very personal recurrent configuration in your [Bacon] work is the interlocking of Crucifixion imagery with that of the butchers shop. The connexion with meat must mean a great deal to you (Sylvester 1993, p. 46). The paradox is that by desecrating the purity of the sacred Bacon was actually adhering to the meaning of the sacred in its etymological sense. In its etymological sense the sacred and the profane cannot be conceived of in a simple dualism. The Latin sacer has two possible translations sacred and accursed. Similarly, the Greek hieros can be translated as sacred and also to qualify instruments of violence and warfare (Girard 1979, p. 262263). Major scholars of the sacred such as Robertson Smith, Mauss, and Durkheim, and lesser-known ones such as Hertz, explore the ambivalence of the sacred and the notion that the impure nature of the sacred aligns it with the profane in many respects. Bacons interpretation of the sacred is therefore atavistic. And also by desecrating and deconstructing the symbol Bacon was making the viewer aware of the special status of these symbols, which have been made commonplace over time. A consequence of reframing these erstwhile binaries is that Bacon is rethinking the conventions of representation and offering a fresh approach to the viewer about how to think about the relationship between inner and outer body and the condition of the bodily. Ofield suggests that his paintings are about the deformation, dissolution, disintegration, decomposition and deconstruction of subjectivity, each insisting that the pictures question mastery and undermine traditional forms of rationality and order (Ofield 2006, p. 38).

Bacon the Nihilist?

It is not surprising to see why some may regard Bacons work as nihilistic. With the abundance of tortured bodies, slumped in their chairs or trapped in confined spaces and the recurring scream or cry, his gaze is pitiless (Schmied 2006, p. 7). On the contrary, his work could be viewed as the products of a misanthrope, who dismissed the spiritual dimensions of life and was compelled by the propensity for violence and death. Russell notes that even in the posthumous (memorial) paintings of George Dyer7 there was not a tinge of conventional pathos (Russell 1993, p. 165). Given the tragic circumstances of Dyers demise, it is peculiar that Bacon did not inject any feeling into his portrayals. He abhorred sentimentality and stood against the neo-romanticism that was

7. George Dyer was Bacons lover from 1964 until the formers death in 1971. On 25 October 1971 Dyer was found dead in the bathroom at Htel des Saint-Pres, the day before the opening of Bacons retrospective exhibition at the Grand Palais, Paris. Bacon painted a series of triptychs to mark this.

REMAKING THE BODY

155

popularized in the 1930s and 1940s. Collectively, the subject matter, palette, and tone of his human forms are more grotesque than uplifting and point to a particular attitude, which is described as nihilistic. Bacon was also prone to make ostensibly nihilistic pronouncements, such as you can be optimistic and totally without hope (Sylvester 1993, p. 80). Bacons work causes profound introspection. We are provided with innumerable studies of the human body articulating bold stances (such as the proximity of the human and the animal) but no solutions. The Baconian landscape is bleak: we are meat, we are potential carcasses and once we are dead there is nothing. For many, this absolute denial of an afterlife is dispiriting and pessimistic. Bacon aligned himself with Nietzschean nihilism and agreed with the assertion that pessimism could be overcome by art. Nietzsches attitude towards art varied in his texts. In certain periods, such as when he wrote The Birth of Tragedy (published in 1872) and then in his final prolific year of 1888, when he wrote Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche displays optimism and expresses the lifeaffirming characteristics of art. Correspondingly, Bacon believed that art had the propensity to encapsulate the human condition of suffering and despair. A common focus shared by Nietzsche and Bacon is the cathartic dimensions of tragedy. In The Birth of Tragedy Nietzsche articulates the regenerative powers that tragedy has, to stimulate, purify and discharge the whole life of the people. Likewise Bacon frequently alluded to Greek tragedy in his work, whether by reference through source material (Oedipus and the Eumenides are two such examples) or more explicitly, such as in statements in interviews. In an interview with Peter Beard, Bacon pays homage to the aesthetic grandeur of Grnewalds Isenheim Altarpiece (in Colmar, c. 15151516):

[The] body studded with thorns like nails, but oddly enough, the form is so grand it takes away from the horror. But that is grand horror in the sense that it is so vitalizing, isnt it; isnt that how people come out of the great tragedies of Greece, the Agamemnon ... People came out as though purged into happiness into a fuller reality of existence. (Geldzahler 1975, p. 1415)

Nietzsches response to nihilism was to quash the metaphysical systems which brought about this situation, that of religion and morality, and to create his own mythology. Bacons response is different. He does not construct an alternative but remains resolute and stoical in the face of the human condition. His attempt to clear away the screens that people live behind and capture the brutality of fact is not nihilistic but realistic and hence revitalizing. His art unlocks the valves of sensation that return the onlooker to life more violently (Sylvester 1993, p. 17). In the post-war climate of the twentieth century Bacon employed the transformative power of art. In his depictions Bacon resists the sanitization of violence that he felt that people had become accustomed to. And he distorted the symbol so that we can see behind it and look at the bloodiness and horror beneath it. In Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion he emphasizes the horror of the Cross as

156

ARYA

a weapon of torture. In his figures of human forms he thwarts our attempts to hide behind a public persona, and leaves us only with our existential predicament of aloneness. The public outcry at the Three Figures can be attributed to the fact that nobody wanted to believe that there was in human nature an element that was irreducibly evil (Russell 1993, p. 10). People wanted respite and comfort in whatever aesthetic form that took. Bacon was not being unduly negative but was merely commenting that in the light of recent atrocities evil does exist and rather than marginalizing this fact, it should be made central in human existence.

Conclusion

In his interrogation of the human body Bacon articulates different ways of perceiving and representing the body in aesthetics. His paintings are provocative and encourage people to think about ideas concerning culture and society. He addresses the following questions: What does it mean to feel, to be in a body and to be alive in the twentieth century? The predicament the viewer finds him/ herself in the modern world with the bombardment of the visual (through advertising and mass media) is that corporeality has become sanitized and marginalized. Sobchack makes an incisive distinction between the viewing of the body and the feeling in the body (my italics):

To say weve lost touch with our bodies is not to say weve lost sight of them. Indeed, there seems to be an inverse ratio between seeing our bodies and feeling them: the more aware we are of ourselves as the cultural artifacts, symbolic fragments and made things that are images, the less we seem to sense the intentional complexity and richness of the corporeal existence that substantiates them. (Sobchack, cited in Warr & Jones 2000, p. 41)

In an interview with Beard, Bacon argues that: weve evolved over millions of years into the state of unnaturalness that we are now in. Humans are totally unnatural. And they vary from race to race in their degrees of unnaturalness (Geldzahler 1975, p. 16). Bacon set out to naturalize the human by defamiliarizing the body. He does this by disfiguring and distorting our perception of what the body looks like. He strips away the public persona of the individual, and all the other veils that we hide behind and places us on the same level as the animal. On a psychological level he takes us back to the existential moment where our identity is in crisis and we are left questioning our purpose. Bacons images make the viewer recoil in disgust. Their distortions are unsightly, pained and the viewer does not want to be associated with them. They look like grotesque deformations of bodies. These seemingly alien interpretations are actually us. Bacon is presenting us with a snapshot of the human condition. Culture has denaturalised us to the extent of estranging us from our condition, which is that of mere flesh. We look at his portrayals and think that

REMAKING THE BODY

157

they are grotesque and this is because we are so estranged from our natural condition. Bacon takes us back to nature and into the slaughterhouse. He told Sylvester: We are meat, we are potential carcasses. If I go into a butchers shop I always think its surprising that I wasnt there instead of the animal (Sylvester 1993, p. 46). The lack of narrative clues means that we cannot deflect the focus of the painting onto the figures and interpret their story but are forced to place ourselves at the centre on the interpretation. The figures are stand-ins for the viewer. In their stripped-down and universalised condition Bacon is making a generic statement about humanity. The images do not simply affect us visually but also haptically. They are prehensile and wound the viewer. In his desire to clear away the veils that we live behind Bacon succeeded in updating the position of the human being in the twentieth century for a contemporary audience in a consistent and developed manner. He paved the way for generations of artists after him, most notably the Young British Artists.8 The Sensation exhibition of 1997 at the Royal Academy can be viewed as an extension of Bacons aspiration that art should unlock the valves of sensation and return the viewer onto life more violently (Sylvester 1993, p.17). In their presentation of a number of themes ranging from love, sex, violence, crime, disease and death, the YBAs aimed to cause a sensation to confront the audience with a series of dislocations that jolt us out of our complacency (Rosenthal et al. 1997, p. 11). Headed by Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin, many of the artists in this grouping articulated their responses to mass consumerism, globalization and other contemporary issues. And instead of moving away from the bodily as had been encouraged in these post-human sensibilities, they returned to it in all its sensations and viscerality. In their explorations of bodily fluids and death (which is a recurring theme in Hirsts dead animals in formaldehyde, such as in The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991) these artists draw on the everyday and the banal (Emins Everyone I Have Slept With 19631995, 1995, being a case in point) with recourse to the scatalogical and the grotesque. But the YBAs part company with Bacon because of their sensationalism. The representation of the body is often present in their work, but it is often sidelined or tangential, and the focus is on the sensation and the spectacular. In Bacons art, however, sensations cannot be extrapolated from the body. The body is of critical importance and is the locus of sensation and perception. Another crucial difference relates to lineage. The YBAs are thoroughly postmodern in their assimilation of sources and ideas whilst Bacons work, although deeply idiosyncratic, is rooted in an art historical tradition, beginning from Bosch and extended to other key influences such as Rembrandt, Goya and Soutine, for example.

8. The term Young British Artists (or the YBAs) is the name given to a number of artists who exhibited their work at the Saatchi Gallery, London from 1992 onwards and are trademarked for their shock tactics.

158

ARYA

In spite of these divergences Bacon remains an heir to the YBAs and other contemporary artists because of the crucial questions that he interrogates in his work. He refers to universal issues regarding the body, the role of evil in society, and the fragmentation of identity.

References

Ades, D. (1985) Web of Images, in Ades, D. & Forge, A. (eds), Francis Bacon, The Trustees of the Tate Gallery and Thames and Hudson, London. Alley, R. (1993) Francis Bacons Place in Twentieth Century Art, in Chiappini, R. (ed.), Francis Bacon, Electra, Milan. Davies, H. M. (1978) Francis Bacon: The Early and Middle Years, 19281958, Garland, New York and London. Davies, H. & Yard, S. (1986) Francis Bacon, Abbeville Press, New York. Deleuze, G. (2003) Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation, trans. Hurley, R., Continuum, London and New York. Gale, M. & Stephens, C. (2008) On the Margin of the Impossible, in Gale, M. & Stephens, C. (eds), Francis Bacon, Tate Publishing, London. Geldzahler, H. (1975) Francis Bacon. Recent Paintings 19681974. March 20June 29, 1975, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Girard, R. (1979) Violence and the Sacred, trans. Gregory, P., The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. Harrison, M. (2008) Bacons Paintings, in Gale, M. & Stephens, C. (eds), Francis Bacon, Tate Publishing, London. Leiris, M. (1983) Francis Bacon: Full Face and in Profile, trans. Weightman, J., Phaidon, Oxford. Rosenthal, N., Shone, R., Maloney, M., Adams, B. & Jardine, L. (1997) Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection: Sensation, Thames and Hudson, London. Russell, J. (1993) Francis Bacon, Thames and Hudson, London. Schmied, W. (2006) Francis Bacon. Commitment and Conflict, Prestel, Verlag, Munich. Sylvester, D. (1993) Interviews with David Sylvester, Thames and Hudson, London. Tinterow, G. (assisted by I. Alteveer) (2008) Bacon and his Critics, in Gale, M. & Stephens, C. (eds), Francis Bacon, Tate Publishing, London. Van Alphen, E. (1992) Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self, Reaktion Books, London. Warr, T. & Jones, A. (eds) (2000) The Artists Body, Phaidon Press, London. Yates, W. (1996) The Real Presence of Evil: Francis Bacons Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Arts, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 2026. Zweite, A. (2006a) Bacons Scream: Observations on Some of the Artists Paintings, in Zweite, A. (ed., in collaboration with M. Muller), Francis Bacon: The Violence of the Real, Thames and Hudson, London, pp. 69104. Zweite, A. (2006b) Introduction, in Zweite, A. (ed., in collaboration with M. Muller), Francis Bacon: The Violence of the Real, Thames and Hudson, London, pp. 1728.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Spiritual Warfare - Mystery Babylon The GreatDocument275 pagesSpiritual Warfare - Mystery Babylon The GreatBornAgainChristian100% (7)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Chord ProgressionDocument6 pagesChord ProgressiongernNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Totoro PapercraftDocument5 pagesTotoro PapercraftIván Javier Ponce Fajardo50% (4)

- AnimationDocument14 pagesAnimationnnnnnat100% (1)

- Ray Keim Free Haunted Project InstructionsDocument8 pagesRay Keim Free Haunted Project InstructionsErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Papercraft Lion Dance / BarogsaiDocument11 pagesPapercraft Lion Dance / BarogsaiSai BlazingrNo ratings yet

- Sterilization and DisinfectionDocument100 pagesSterilization and DisinfectionReenaChauhanNo ratings yet

- Goya and WitchcraftDocument29 pagesGoya and WitchcraftErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Https WWW - Gov.uk Government Uploads System Uploads Attachment Data File 274029 VAF4ADocument17 pagesHttps WWW - Gov.uk Government Uploads System Uploads Attachment Data File 274029 VAF4ATiffany Maxwell0% (1)

- Lesson 12 Elements of A Concept PaperDocument4 pagesLesson 12 Elements of A Concept PaperTrending Now100% (2)

- Carolingian Art and PoliticsDocument41 pagesCarolingian Art and PoliticsErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Art Education and CitizenryDocument10 pagesArt Education and CitizenryErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Thesis - The Problem of Character in Contemporary CircusDocument110 pagesThesis - The Problem of Character in Contemporary CircusErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Deweys Aesthetics in Art EducationDocument15 pagesDeweys Aesthetics in Art EducationErick FloresNo ratings yet

- How Can You Increase Smartphone Battery Life - WIREDDocument5 pagesHow Can You Increase Smartphone Battery Life - WIREDErick FloresNo ratings yet

- El Nuevo Disco de U2 Es SpamDocument4 pagesEl Nuevo Disco de U2 Es SpamErick FloresNo ratings yet

- How Can You Increase Smartphone Battery Life - WIREDDocument5 pagesHow Can You Increase Smartphone Battery Life - WIREDErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Assembly Instructions.: WALL PlaqueDocument1 pageAssembly Instructions.: WALL PlaqueErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Freire Aesthetic Through RanciereDocument16 pagesFreire Aesthetic Through RanciereErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Sahara 2 Days 1 Night.: 65. Per PersonDocument2 pagesSahara 2 Days 1 Night.: 65. Per PersonErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Memories For The Future: U D e I D e T H WDocument1 pageMemories For The Future: U D e I D e T H WErick FloresNo ratings yet

- A FREE Project From Ray Keim - Haunted Dimensions Do Not Resell © Ray KeimDocument2 pagesA FREE Project From Ray Keim - Haunted Dimensions Do Not Resell © Ray KeimErick FloresNo ratings yet

- F1XDocument1 pageF1XErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Salem Mask Army of Two White Version by ZRP PapercraftDocument4 pagesSalem Mask Army of Two White Version by ZRP PapercraftErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Goya Witnessing The Disasters of WarDocument28 pagesGoya Witnessing The Disasters of WarErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Scabbard in STDocument1 pageScabbard in STErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Saint Basil's Cathedral Papercraft Assembly GuideDocument0 pagesSaint Basil's Cathedral Papercraft Assembly GuideErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Golden PlaqueDocument2 pagesGolden PlaqueErick FloresNo ratings yet

- F1CDocument1 pageF1CErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Goya LanguageDocument15 pagesGoya LanguageErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Rocot Planters Re-Using Home JunkDocument27 pagesRocot Planters Re-Using Home JunkErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Paper Craft MoaiDocument0 pagesPaper Craft MoaiFrancisco Xavier Ramirez TapiaNo ratings yet

- Goya and PerceptionDocument29 pagesGoya and PerceptionErick FloresNo ratings yet

- The Face Plate The Face Plate The Face Plate The Face Plate: - Assembly Instructions (Page1)Document2 pagesThe Face Plate The Face Plate The Face Plate The Face Plate: - Assembly Instructions (Page1)Erick FloresNo ratings yet

- Broadsword in STDocument2 pagesBroadsword in STErick FloresNo ratings yet

- Khandelwal Intern ReportDocument64 pagesKhandelwal Intern ReporttusgNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document11 pagesChapter 1Albert BugasNo ratings yet

- Plo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentDocument22 pagesPlo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentkrystelNo ratings yet

- Term2 WS7 Revision2 PDFDocument5 pagesTerm2 WS7 Revision2 PDFrekhaNo ratings yet

- Decision Support System for Online ScholarshipDocument3 pagesDecision Support System for Online ScholarshipRONALD RIVERANo ratings yet

- Pure TheoriesDocument5 pagesPure Theorieschristine angla100% (1)

- Absenteeism: It'S Effect On The Academic Performance On The Selected Shs Students Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesAbsenteeism: It'S Effect On The Academic Performance On The Selected Shs Students Literature Reviewapi-349927558No ratings yet

- Zeng 2020Document11 pagesZeng 2020Inácio RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Theories of LeadershipDocument24 pagesTheories of Leadershipsija-ekNo ratings yet

- Alphabet Bean BagsDocument3 pagesAlphabet Bean Bagsapi-347621730No ratings yet

- MID Term VivaDocument4 pagesMID Term VivaGirik BhandoriaNo ratings yet

- Batman Vs Riddler RiddlesDocument3 pagesBatman Vs Riddler RiddlesRoy Lustre AgbonNo ratings yet

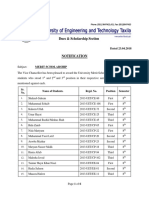

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDocument6 pagesDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Maam MyleenDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Maam MyleenRochelle RevadeneraNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship and Small Business ManagementDocument29 pagesEntrepreneurship and Small Business Managementji min100% (1)

- Cover Letter IkhwanDocument2 pagesCover Letter IkhwanIkhwan MazlanNo ratings yet

- San Mateo Daily Journal 05-06-19 EditionDocument28 pagesSan Mateo Daily Journal 05-06-19 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Reduce Home Energy Use and Recycling TipsDocument4 pagesReduce Home Energy Use and Recycling Tipsmin95No ratings yet

- Intro to Financial Management Chapter 1 SummaryDocument11 pagesIntro to Financial Management Chapter 1 SummaryweeeeeshNo ratings yet

- UAE Cooling Tower Blow DownDocument3 pagesUAE Cooling Tower Blow DownRamkiNo ratings yet

- It ThesisDocument59 pagesIt Thesisroneldayo62100% (2)

- Inver Powderpaint SpecirficationsDocument2 pagesInver Powderpaint SpecirficationsArun PadmanabhanNo ratings yet

- Extra Vocabulary: Extension Units 1 & 2Document1 pageExtra Vocabulary: Extension Units 1 & 2CeciBravoNo ratings yet

- UNIT 1 Sociology - Lisening 2 Book Review of Blink by Malcolm GladwellDocument9 pagesUNIT 1 Sociology - Lisening 2 Book Review of Blink by Malcolm GladwellNgọc ÁnhNo ratings yet

- Cloud Computing Basics and Service ModelsDocument29 pagesCloud Computing Basics and Service ModelsBhupendra singh TomarNo ratings yet