Professional Documents

Culture Documents

He Design Stirling Engine

Uploaded by

Vlcek VladimirCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

He Design Stirling Engine

Uploaded by

Vlcek VladimirCopyright:

Available Formats

Design of a 2.

5kW Low Temperature Stirling Engine for Distributed Solar Thermal Generation

Mike He and Seth Sanders

University of California - Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, 94720, USA

This paper focuses on the design of a Stirling engine for distributed solar thermal applications. In particular, we design for the low temperature dierential that is attainable with distributed solar collectors and the low cost that is required to be competitive in this space. We will describe how these considerations drive the core design, the methodology for improving the design, and summarize progress made in fabrication of the engine for experimentation. Stirling engines can have broad signicance and technological advantages for distributed renewable energy applications. A key advantage of a solar thermal system is that they can incorporate thermal energy storage in a cost-eective manner. In addition, Stirling engine systems are fuel-exible with respect to the source of thermal energy and unprocessed waste heat can be harvested for CHP purposes as well. The ability to extract unconverted thermal energy for waste heat applications greatly improves the overall thermal eciency of the system.

I.

Introduction

to challenges in order to Renewable energy technology will needTheseaddress importantsources, a problemtomostbe adopted at high penetrations in a modern electric grid. include achieving low enough cost be economically attractive and mitigating the variability inherent in renewable energy directly addressed by energy storage. We propose a Stirling-engine-based solar thermal system for distributed generation of electricity as a renewable energy technology that addresses these challenges. The proposed system, as shown in Figure 1, is comprised of a passive solar collector, a hot thermal storage subsystem, a Stirling engine for energy conversion, and a waste heat recovery system to implement combined heat and power. The system as envisioned would be appropriate for residential solar generation or on a small commercial building scale. The Stirling engine is a key component of the system and is the focus of the present paper. The proposed solar thermal system incorporates thermal energy storage as a buer between input solar energy, which is highly variable, and output generation. As a result, it provides a stable level of generation that is predictable, controllable, and schedulable. In addition, the exibility of the Stirling engine with respect to fuel source allows such a system to consume alternative fuels, such as natural gas, in a complementary fashion to operate in the absence of solar insolation. The collector and storage tank are mass-produced components that are already available at low cost. By designing the Stirling engine with low cost in mind, the authors propose that the overall system can be highly cost competitive when compared to other distributed renewable technologies, most notably rooftop photovoltaics. With regards to Stirling engine design, one signicant challenge is that the hot-side temperatures possible with the proposed system are lower than in typical Stirling applications, where combustion of fuel or radioisotope thermal energy sources provides higher quality heat. As such, the major innovative design characteristics of the Stirling engine to be described in the paper are the ways in which the engine is designed to achieve adequate eciency at low cost and low hot-side temperatures.

Ph.D. Professor,

Student, EECS Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1770 EECS Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1770

1 of 8 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Figure 1. Schematic of the proposed Stirling engine system.

II.

Motivation

Stirling engines have found various applications as energy converters for highly-concentrated solar thermal plants, coolers and heat pumps, and other specialized applications such as space ight. This design diers from typical applications in that we design for lower temperature dierentials and that low cost of materials and fabrication is a priority. In contrast, size and mass are of lower importance. This application area has been the focus of less research in the literature and warrants additional investigation. In particular, as renewable energy and energy eciency have become more critical areas of research in recent years, the design and development of a Stirling engine system that can be commercialized for thermal energy generation applications and as a combined heat and power system would add signicant value.

III.

A. Design Goals

Design

The core design goal is achieving high eciency at low cost. In the space of energy applications, the low price of energy requires technologies to satisfy tight constraints on cost and produce enough energy to be competitive. Previous analytic and empirical results from the design and development of low-power engine prototypes in this space informed many of the design goals and decisions of this prototype.1, 2 In order to achieve adequate eciency and performance at low temperature dierentials, we rst focused on designing high performance heat exchangers with the goal of minimizing all temperature drops along the path of thermal energy ow from input to output. By maximizing the temperature dierential available to the Stirling cycle itself, higher performance can be achieved at low temperature dierential. Simultaneously, the heat exchanger design had to be low cost, precluding high performance designs that require more complicated features. As a result, the design was chosen for simplicity of fabrication. B. Design Methodology

The design process for the engine consisted of thermal analysis and adiabatic cycle simulations feeding into parameter optimizations, and tempered with evaluation of cost and fabrication simplicity. The rst step of the design process was to create a proposed conguration and layout, then characterize the performance of the heat exchangers based on the designed geometry, using thermal physics and analytic and empirical uid dynamics models from literature (e.g.3 ). This information was then used in an adiabatic cycle simulation to predict cycle performance, internal pressure waveforms, and cycle losses. This stage allowed us to characterize the predicted performance of

2 of 8 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

the engine in terms of eciency, output power, and complete a picture of losses. Finally, optimization procedures over dierent sets of parameters were performed to rene the results and maximize predicted performance. A wide range of options was considered for the overall engine geometric conguration, heat exchanger geometry, working uid composition, and piston motion mechanics (free-piston vs kinematic). C. Heat Exchangers and Regenerator

In order to achieve adequate eciency and performance at low temperature dierentials, the design of the heat exchanger components focused on reducing temperature drops as much as possible and reducing loss components, such as gas ow friction, conduction losses, and gas hysteresis losses. The design was chosen to also reduce the amount of machining required and to use low cost materials in order to reduce overall cost. The key tradeo in achieving high eciency is between the regenerator and heat exchanger eectiveness and the ow loss in these components. Ultimately the best performance is achieved by designing for small hydraulic diameters and wide cross-sectional areas.3, 4 The overall engine geometry was designed with high cross-sectional areas to the direction of working uid ow in order to reduce ow friction losses while not compromising wetted area for heat transfer. The regenerator was chosen to be ultra-ne berglass mesh, compacted to achieve the desired porosity for heat transfer and ow loss properties. This material allows for small hydraulic diameter for improved heat transfer with very lost cost. The hot-side and cold-side heat exchangers are comprised of aluminum plates for heat transfer from an externally pumped hot or cold liquid, integrated with ne copper mesh weaves to transfer thermal energy to the internal working uid. Expected temperature drops for the various heat exchanger components are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Expected temperature drops in heat exchanger components

Component Hot-side Liquid to Metal Hot-side Metal to Air Cold-side Liquid to Metal Cold-side Metal to Air

T emperatureDrop(C) 1.79 1.26 2.42 1.09

D.

Adiabatic Model

An adiabatic model of the Stirling cycle was used to calculate expected performance.5 The adiabatic model assumes that the net heat transferred over a cycle from the hot side to the cold side, plus work produced, is equal to the heat transferred by the heat exchangers. This analysis is more detailed than isothermal models of the Stirling cycle and, as a result, no closed-form solution exists, but rather requires numeric simulation. What is gained is greater accuracy of results.5 Internal pressure and temperature waveforms as predicted by the adiabatic model are plotted in Figure 2. The heat exchanger characterization forms an important input into this process, providing information on thermal ows and losses. The outputs of this step are performance metrics, such as eciency and mechanical output power. The losses that are accounted for in this model include enthalpy losses from uncaptured heat in the regenerator, ow frictional losses through the engine, conduction losses, gas hysteresis losses, enthalpy losses from leakages, and other smaller losses.5, 6 A full diagram of energy ows and losses appears in Figure 5. E. Optimization

This analysis was folded into an optimization routine that scanned over the parameter space and rened design parameters to improve design performance. This step was key in guiding the nal design process. Key parameters that were explored include regenerator geometry, heat exchanger meshes, and displacer and power piston strokes. Example graphs used during the optimization process are displayed in Figure 3 and 4. An important conclusion drawn through this process is that the most signicant design tradeo is between increasing regenerator eectiveness by increasing the length of the regenerator stack, and the increased gas

3 of 8 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

(a) Internal pressure waveform from adiabatic model.

(b) Temperature waveforms from adiabatic model.

Figure 2. Simulation results from the Adiabatic model of the Stirling cycle.

(a) 30 bar Air, 20 Hz Freq

(b) 30 bar Air, 30 Hz Freq

(c) 30 bar He, 20 Hz Freq

(d) 30 bar He, 30 Hz Freq

Figure 3. Plots of example optimization graphs. These graphs show power output and eciency contours plotted against piston strokes, plotted for dierent test cases of engine frequency and working uid composition.

4 of 8 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

(a) 30 bar Air, 20 Hz Freq

(b) 30 bar Air, 30 Hz Freq

(c) 30 bar He, 20 Hz Freq

(d) 30 bar He, 30 Hz Freq

Figure 4. Overall eciency (top) and regenerator losses (bottom) as a function of regenerator length.

5 of 8 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

ow friction that results. Other signicant trade-os include the analogous example of heat exchangers, increasing pressure versus frequency, and piston strokes. F. Selected Design

The selected engine design for this application is at an operating point of 20Hz with 30 bar pressurized air as the working uid. Operating at 20Hz provides good balance between output power and losses, and also allows the engine to interface with a 6-pole alternator to achieve an electrical frequency of 60Hz, allowing direct grid connection if desired. A gamma conguration is chosen as a natural geometric t with the heat exchangers and to reduce sealing challenges. The rated power output of the engine was designed at 2.5 kW, a level appropriate for satisfying the majority of demands in small buildings, residential or commercial. A kinematic piston design was chosen to simplify the design with respect to the dynamics of the system and the fabrication process.

Table 2. Design Parameters

Design Quantity Nominal Power Output Thermal-Electric Eciency Fraction of Carnot Eciency Hot Side Temperature Cold Side Temperature Working Gas (Air) Pressure Engine Frequency Electrical Output Regenerator Eectiveness Piston Swept Volume

Value 2.525 kW 21% 65% 180 C 30 C 25 bar 20 Hz 60Hz, 3 0.9967 2.2 L

The heat exchangers were optimized for the tradeo between heat transfer eectiveness and ow frictional losses. The objective is to provide a high conductivity, high cross-sectional area thermal path for input heat to ow. The large total open area presented to the gas ow is designed to lower ow resistance while providing for low temperature drops in the thermal path. The displacer piston was designed to be fabricated from two light aluminum plates and a hollow interior reinforced with standos in order to reduce mass and simplify fabrication. The power piston is a solid steel cylinder that was weighted to achieve resonance with the gas spring of the working uid. Both pistons were designed with clearance seals to reduce cost and increase longevity. The swept volume of the power piston per stroke is 2.2L. The predicted performance of this engine at a rated output power of 2.5kW is approximately 21% thermal to mechanical conversion eciency. This represents approximately 63% of the Carnot eciency at these temperatures. The largest loss component is enthalpy loss from uncaptured heat in the regenerator, followed by ow frictional loss in the regenerator, then by ow losses in the heat exchangers. Important performance and design parameters are listed in Table 2. A gure of predicted energy ows in the engine, including thermal ows and losses, is given in Figure 5.

IV.

Fabrication and Experimental Setup

The fabrication process of the Stirling engine design was relatively simple. The most complicated machined part, the heat exchangers, is simpler than typical high performance heat exchangers, consisting of a at aluminum plate and requiring two milling steps. Other components that required machining include the crankshaft assembly, which was modeled after automotive crankshafts to simplify fabrication. To simplify sealing requirements, the crankcase was contained in the fully pressurized working environment. O-theshelf bearings are used in the crankshaft assembly. Two large steel plates anchor the engine and provide structural support, but do not require signicant machining. The copper mesh weaves are readily available as o-the-shelf product. The power piston was coated with a Teon-based coating to reduce friction.

6 of 8 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Figure 5. Predicted energy ows in the engine.

(a) CAD model.

(b) Engine photograph.

Figure 6. Selected components from fabricated engine.

7 of 8 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Pictures of some of the components in the fabricated prototype are shown in Figure 6. The next step is to perform experiments to empirically validate the design predictions. Important data to measure include cycle performance characteristics such as the internal pressure waveform, heat exchanger performance, loss components, and overall power output and eciency.

V.

Conclusion

Due to the relatively low hot-side temperatures as compared to traditional Stirling engine applications, high overall eciency is harder to achieve and requires careful design in maximizing heat transfer capabilities of the heat exchangers in order to reduce temperature drops. Careful optimization of various loss components versus metrics such as output power is an important part of the design process. The Stirling engine system as described was designed with these considerations in mind. Furthermore, the engine must be designed at low cost to be competitive for energy applications. This requires component geometries and materials to be designed to simplify fabrication and utilize low-cost materials and mass-produced components. The overall engine geometry and components such as the regenerator, heat exchanger, and mechanical components were designed to meet these constraints. The Stirling engine as designed is expected to achieve relatively high performance as a fraction of the Carnot eciency and have low-cost in fabrication in mass production. We will be conducting experimentation to verify the design performance in the near future.

VI.

Acknowledgments

M. He thanks the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and NSF Award 0932209, LoCal - A Network Architecture for Localized Electrical Energy Reduction, Generation and Sharing, for supporting this project.

References

1 Minassians, A. D. and Sanders, S. R., A Magnetically-Actuated Resonant-Displacer Free-Piston Stirling Machine, 5th International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference and Exhibit (IECEC), June 25-27 2007. 2 Minassians, A. D. and Sanders, S. R., Multi- Phase Stirling Engines, 6th International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference and Exhibit (IECEC), July 28-30 2008. 3 Makoto, T., Iwao, Y., and Fumitake, C., Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics of the Stirling Engine Regenerator in an Oscillating Flow, JSME international journal, Vol. 33, No. 2, 05-15 1990, pp. 283289. 4 Incropera, F. P., Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer , John Wiley & Sons, 2006. 5 Urieli, I. and Berchowitz, D., Stirling Cycle Engine Analysis, Adam Hilger, Bristol, UK, 1984. 6 Minassians, A. D., Stirling Engines for Low-Temperature Solar-Thermal-Electric Power Generation, Ph.D. thesis, University of California - Berkeley, 2007.

8 of 8 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Stirling EngineDocument4 pagesStirling Engineanon-124856100% (7)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- 83 6khzDocument20 pages83 6khzAnonymous o7bhrwXtWGNo ratings yet

- (The International Cryogenics Monograph Series) Graham Walker (Auth.) - Cryocoolers - Part 2 - Applications-Springer US (1983) PDFDocument420 pages(The International Cryogenics Monograph Series) Graham Walker (Auth.) - Cryocoolers - Part 2 - Applications-Springer US (1983) PDFlivrosNo ratings yet

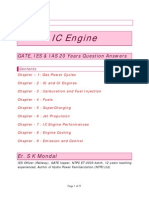

- IC Engine IES GATE IAS 20 Years Question and AnswersDocument77 pagesIC Engine IES GATE IAS 20 Years Question and AnswersSaajal Sharma96% (26)

- Cryog. Engineering - Software Solutions Part-III-A PDFDocument235 pagesCryog. Engineering - Software Solutions Part-III-A PDFrikiNo ratings yet

- Stirling Engine ReportDocument20 pagesStirling Engine ReportRajeshwar Singh Urff Raj100% (1)

- Saab Kockums-A26 Brochure A4 Final Aw ScreenDocument16 pagesSaab Kockums-A26 Brochure A4 Final Aw ScreenVictor Pileggi100% (2)

- Engineer Guide Tank Gauging PDFDocument104 pagesEngineer Guide Tank Gauging PDFnknicoNo ratings yet

- NF68S-M2 0601C BDocument90 pagesNF68S-M2 0601C BMarcos BarragànNo ratings yet

- LM4132Document20 pagesLM4132Vlcek VladimirNo ratings yet

- LMP 7732Document18 pagesLMP 7732Vlcek VladimirNo ratings yet

- Thermal AccumulatorsDocument5 pagesThermal AccumulatorsVlcek VladimirNo ratings yet

- Thesis FulltextDocument132 pagesThesis Fulltextdormouse1No ratings yet

- gs950-24 DsDocument2 pagesgs950-24 DsVlcek VladimirNo ratings yet

- Vista Client InstallqsDocument2 pagesVista Client InstallqsAlison RichmondNo ratings yet

- MUM 2008 Workshop on IP Flow Routing, Mangle and QoSDocument35 pagesMUM 2008 Workshop on IP Flow Routing, Mangle and QoSVlcek VladimirNo ratings yet

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- AutoCAD 2000 Visual Lisp TutorialDocument136 pagesAutoCAD 2000 Visual Lisp TutorialHimanishBhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Manufacturing and testing of a V-type Stirling engineDocument11 pagesManufacturing and testing of a V-type Stirling engineﺃﻧﺲﺻﺪﻳﻖNo ratings yet

- Calcul UkDocument5 pagesCalcul UkJeremyNo ratings yet

- Thermal Engineering IIDocument99 pagesThermal Engineering IIabinmace100% (1)

- Flameless Combustion and Its ApplicationsDocument12 pagesFlameless Combustion and Its ApplicationsDamy ManesiNo ratings yet

- Ic EngineDocument17 pagesIc EngineRajeswar KumarNo ratings yet

- (28-6-3) NPTEL - CryocoolersDocument33 pages(28-6-3) NPTEL - CryocoolersThermal_Engineer100% (1)

- Analysis of Stirling Engine and Comparison With Other Technologies Using Low Temperature Heat Sources PDFDocument73 pagesAnalysis of Stirling Engine and Comparison With Other Technologies Using Low Temperature Heat Sources PDFWoo GongNo ratings yet

- Stirling CryocoolerDocument7 pagesStirling Cryocooler111Neha SoniNo ratings yet

- Instrumentation - Liquid Level: MAY 1994 Page 1 of 8Document8 pagesInstrumentation - Liquid Level: MAY 1994 Page 1 of 8Jhonny Rafael Blanco CauraNo ratings yet

- Stirling Engine by Bilegsaikhan SDocument12 pagesStirling Engine by Bilegsaikhan SbilegsaikhanNo ratings yet

- Motor StirlingDocument15 pagesMotor Stirlingcarlos caizaNo ratings yet

- 3B Scientific® Physics: Stirling Engine G U10050Document4 pages3B Scientific® Physics: Stirling Engine G U10050kbabu786No ratings yet

- Bruce Crowder: Professional ExperienceDocument3 pagesBruce Crowder: Professional ExperienceBruceNo ratings yet

- Stirling Engine & Applications Project SeminarDocument32 pagesStirling Engine & Applications Project SeminarLASINNo ratings yet

- 1 - Pedal Drilling Machine ReportDocument26 pages1 - Pedal Drilling Machine ReportParamesh Waran [049]No ratings yet

- Final Seminar AnilDocument39 pagesFinal Seminar Anilharry tharunNo ratings yet

- Candle Power Stirling Engine PDFDocument4 pagesCandle Power Stirling Engine PDFFodor EmericNo ratings yet

- Experiment 1 - Orifice and Jet Flow MeterDocument36 pagesExperiment 1 - Orifice and Jet Flow MeterKim Lloyd A. BarrientosNo ratings yet

- 2500 OR 2503 SERIES CONTROLLER/TRANSMITTER INSTRUCTION MANUALDocument32 pages2500 OR 2503 SERIES CONTROLLER/TRANSMITTER INSTRUCTION MANUALJesus GBNo ratings yet

- Stirling Engine Project ReportDocument17 pagesStirling Engine Project ReportelangandhiNo ratings yet

- Later Single-Cylinder EnginesDocument14 pagesLater Single-Cylinder EnginesImade EmadeNo ratings yet

- ME 400 Project & Thesis Design & Simulation of an Alpha Type Stirling EngineDocument25 pagesME 400 Project & Thesis Design & Simulation of an Alpha Type Stirling Enginesuraj dhulannavarNo ratings yet