Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sam Ashman Economics and Political Economy Today Introduction To The Symposium On Fine and Milonakis 2012 Historical Materialism Vol20 No3 Pp3 8

Uploaded by

Hyeonwoo KimOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sam Ashman Economics and Political Economy Today Introduction To The Symposium On Fine and Milonakis 2012 Historical Materialism Vol20 No3 Pp3 8

Uploaded by

Hyeonwoo KimCopyright:

Available Formats

Historical Materialism 20.

3 (2012) 38

brill.com/hima

Economics and Political Economy Today: Introduction to the Symposium on Fine and Milonakis

Sam Ashman

University of Johannesburg pdf5@uj.ac.za

Abstract Economics has long been the dismal science. The crisis in classical political economy at the end of the nineteenth century produced radically difffering intellectual responses: Marxs reconstitution of value theory on the basis of his dialectical method, the marginalists development of subjective value theory, and the historical schools advocacy of inductive and historical reasoning. It is against this background that economics was established as a discrete academic discipline, consciously modelling itself on maths and physics and developing its focus on theorising exchange. This entailed extraordinary reductionism, with humans regarded as rational, self-interested actors, and class, society, history and the social being excised from economic analysis. On the basis of this narrowing of its concerns, particularly from the 1980s onwards, economics has sought to expand its sphere of influence through a form of imperialism which seeks to apply mainstream economic approaches to other social sciences and sees economics as the universal grammar of social science. The implications of this shift are discussed in Ben Fine and Dimitris Milonakiss two volumes, where they analyse the fate of the social, the political and the historical in economic thought, and assess the future for an inter-disciplinary critique of economic reason. Keywords economics, political economy, history of economic thought

Economics has been the dismal science since at least as early as 1849 when Thomas Carlyle labelled it as such. This was initially as a description of Malthuss arguments about population growth (which later would become known as the dismal theorem) and then it was repeated in his essay, Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question.1 Carlyle argued that slavery ought to be re-introduced in the West Indies to regulate the labour market. Economics was dismal because it located everything in supply and demand while, for Carlyle, compulsion and slavery were much brighter and preferable. Marx famously distinguished between classical and vulgar economy, the diffference between

1.Carlyle 1849.

Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2012 DOI: 10.1163/1569206X-12341263

S. Ashman / Historical Materialism 20.3 (2012) 38

the disinterested inquirer and the hired prize-fighter. But, for Marx, the emergence of vulgar economy was not simply an exercise in apologetics, it was a response to the intellectual problems posed by classical political economy itself, and in particular Ricardos conception of value.2 Vulgar economy refused to go behind surface phenomena (and so provided an apology for capital). Today the academic discipline of economics is a deeply entrenched pseudo-science whose most glaring recent failure has been its inability to predict, analyse or respond to the global crisis. Mainstream economics remains impervious to criticism, arrogant about its achievements, aggressive and imperious in addressing the concerns of other disciplines on its own reductionist and narrow terms, and secure in its institutional power. Churchill thought history to be a subject written by the victors, but in economics it is written by the vanquished with the history of economic thought (HET), and economic methodology, the concerns of the remaining heterodox (postKeynesian, Austrian Institutionalist, and Marxist) economists, and those in other disciplinary locations. This dominance is reproduced in the training of PhD students, in hiring, in promotion, and in publishing.3 However strong the critiques of the mainstream may be, these alternatives are ignored, with the Cambridge capital controversy of the 1960s the only true debate in the sense that the mainstream on this occasion engaged substantively with its critics. So, plus a change, plus cest la mme chose. Although there has been change over time, and although bourgeois individualism clearly predates marginalism, the degeneration of economics is deeply rooted in the marginalist revolution of the 1870s.4 The crisis of the Ricardian school and the classical politicaleconomy tradition produced profoundly diffferent intellectual responses: Marxs reconstitution of value theory on the basis of his dialectical method; the marginalists refinement of subjective value theory through the reinvention of the concept of marginal utility (which, through Carl Menger, would also give rise to the Austrian school of economics); and the German historical schools rejection of marginalism and advocacy of an inductive and historical method, which would later produce evolutionary or institutional economics and whose most celebrated representatives are Weber and Schumpeter. Marginalisms three key theorists, William Stanley Jevons, Carl Menger and Lon Walras whose ideas remain at the core of neoclassical thinking saw the basis of the new science of economics as lying in the theory of exchange. For Walras, the theory of exchange is based on the proportionality of prices to intensities of last wants satisfied (i.e. to final degrees of utility). Things obtain

2.The lengthiest discussion of which is contained in Marx 1863. See also King 1979. 3.Fullbrook (ed.) 2003; Lee 2007. 4.For a diffferent account, see Hodgson 2011.

S. Ashman / Historical Materialism 20.3 (2012) 38

their value in exchange from scarcity, so scarcity and choice become the chief subject matters in economics: the process of exchange and the determination of prices under hypothetical conditions of free competition. And, as value in exchange is a magnitude that is measurable, for Walras the theory of value in exchange is a branch of mathematics.5 The new approach meant the abandonment of classical political economys macro-dynamic view of the economy and its concern with growth and distribution, and its replacement with static-equilibrium analysis and the desire to model economics on maths and physics.6 As part of this shift, the new science of economics was to be separated from the arts and applied sciences and from ethics and the moral sciences. The Methodenstreit, or battle of methods, which took place between Menger and Gustav Schmoller in the early 1880s, highlighted the diffferences between marginalism and the German historical school as they fought over deductive and inductive reasoning, theory versus narrative, and universality and specificity, though with the German school vulnerable to the charge that it lacked theory. But while mainstream economics consolidated on marginalist principles in the 1930s under the definition provided by Robbins, as the study of scarcity and the science of choice, economics the discipline remained diverse prior to WWII, with, in addition to the Historical School, Old Institutionalism strong in the United States, and later Keynesianism and (Classical) Development Economics protected spheres for a time. It was not until the formalist revolution of the 1950s onwards that the discipline was mathematised intensively and being an economist defined by the adherence to certain techniques and technical apparatus.7 This complex journey and its outcomes are the subject of Ben Fine and Dimitris Milonakiss two books, the first of which won the Gunnar Myrdal Prize and the second the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize.8 They are particularly welcome for those involved in teaching HET and political economy, whatever the disciplinary location. The books are presented as a staging post in what is a continuing programme of work with a third volume promised on method and theory in the evolution of the study of economic history.9 But the subject matter is of broader interest than simply that of the specialist, tied as it is to the evolution of the social sciences as a whole. Fine and Milonakiss overall argument is in many ways quite simple: that the passage

5.Milonakis and Fine 2009, p. 95. 6.Lou 1997. 7.Blaug 2003. 8.Fine and Milonakis 2009; Milonakis and Fine 2009. See also Fine and Milonakis 2011. 9.See the Preface to Fine and Milonakis 2009.

S. Ashman / Historical Materialism 20.3 (2012) 38

from classical political economy (and its concern with the capitalist economy in toto) to mainstream economics, and the emergence of discrete academic disciplines, entailed a triple reductionism that individualises, de-socialises and de-historicises economic analysis. And that, secondly, it is on the basis of this narrowing of approach and the focus on formal, technical and mathematical analysis that has come the enlargement of the scope of economists interests.10 So we have the reduction to the individual as the basic unit of analysis with the economy the aggregate of individuals, and with individuals conceived in a particular way (as rational, self-interested, utility-maximisers); we have the reduction of the economic to the market, and to market relations understood without any social basis, and within an equilibrium framework; and we have an ahistoric reductionism the market as universal, divorced from history. Classes, institutions and history are excised from analysis, the concern of other disciplines. Economics imperialism a term and phenomenon dating back at least as far as 1933 emerged with a vengeance from the 1950s onwards in Gary Beckers economic approach which applies neoclassical technique to other areas of social life but treating these as if they were markets and all behaviour as reducible to economic rationality, e.g. the family, crime, human capital.11 But Fine and Milonakis argue that more typical of economics imperialism than Becker are the strands which have emerged from the 1980s onwards that prefer to interpret the social as a response to the imperfect workings of markets, as in the new institutional economics, or the new economic history, or the new economic geography. This approach has widened the scope of economics imperialism and its incursion into other disciplines. For the advocates of economics imperialism there is only one social science... scarcity, cost, preferences, opportunities, etc. are truly universal in application.... Thus economics does really constitute the universal grammar of social science.12 For others, the core principles of economics, rationality and equilibrium, may serve to unify social science within the foreseeable future.13 Recent variants include freakonomics though Fine and Milonakis emphasise how this populist economics imperialism difffers from other strands and neuroeconomics, which claims to link economic behaviour with neural mechanisms. Fine and Milonakiss goal is to illuminate the parlous state of economics today through analysing the trajectory of the social and the historical element in economic thought and the consequences for economics of, firstly, its abandonment, and then, secondly, its re-introduction on a narrow and empty

10.Interestingly, as recognised by Coase 1978. 11. Becker 1976. 12.Fine and Milonakis 2009, p. 14. 13.Ibid.

S. Ashman / Historical Materialism 20.3 (2012) 38

basis.14 The volumes cover a huge amount of ground, and include Weber, Schumpeter, the Austrian school, and the German and British historical schools, in addition to those thinkers more usually covered by HET. With subject matter ranging this widely, the contributors to the symposium have much from which to choose their focus. Most deal with the issues raised in the first volume (from classical political economy to the formalist revolution) rather than the second (economics imperialism from Becker onwards). Steve Fleetwood, John King and David McNally broadly agree with the central arguments presented across the two volumes and focus their discussion more on points of emphasis and interpretation, whereas Roger Backhouse raises more substantial disagreements over HET. Fine and Milonakiss stated aim is to provide an alternative approach based on class, capital, and value theory, and the two volumes contain an outstanding chapter on Smith, Ricardo and Marx and a further excellent discussion of the historical logic of economics imperialism.15 But value theory has a somewhat undulating presence across the two volumes as whole with little mention in the second volume except for the Conclusion. The discussion of Marxs methodology is compressed into particular parts of the volumes with the efffect that at times it appears as if the methodological options before us are limited to inductive versus deductive reasoning, though Fine and Milonakis clarify their views in the reply to this symposium.16 So what follows is wide-ranging in both subject matter and implications. The future of political economy is less explored by the contributors, and appeals to broad-church pluralism, however correct, only make sense within the context of the intolerance of the discipline of economics itself, and, of course, much divides the Marxist, Austrian Institutionalist and post-Keynesian alternatives to the mainstream. But the key challenge for the future remains in the development of the interdisciplinary and systemic study of capitalism.

References

Becker, Gary S. 1976, The Economic Approach to Human Behaviour, Chicago: Chicago University Press. Blaug, Mark 2003, The Formalist Revolution of the 1950s, Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 25, 2: 14556.

14.There are other accounts of this sorry story, or at least of its constituent parts. For example, see Clarke 1982; Davis 2003; Fullbrook (ed.) 2003; Hodgson 2001; Tabb 1999. 15.In Milonakis and Fine 2009 and Fine and Milonakis 2009 respectively. 16.See Callinicos 2011.

S. Ashman / Historical Materialism 20.3 (2012) 38

Callinicos, Alex 2011, Book Review: From Political Economy to Economics, Science and Society, 75, 2: 2679. Carlyle, Thomas 1849, Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question, available at: <http://en. wikisource.org/wiki/Occasional_Discourse_on_the_Negro_Question>. Clarke, Simon 1982, Marx, Marginalism and Modern Sociology: From Adam Smith to Max Weber, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Coase, Ronald H. 1978, Economics and Contiguous Disciplines, Journal of Legal Studies, 7, 2: 20111. Davis, John B. 2003, The Theory of the Individual in Economics: Identity and Value, London: Routledge. Fine, Ben and Dimitris Milonakis 2009, From Economics Imperialism to Freakonomics: The Shifting Boundaries between Economics and Other Social Sciences, London: Routledge. 2011, Useless but True: Economic Crisis and the Peculiarities of Economic Science, Historical Materialism, 19, 2: 331. Fullbrook, Edward (ed.) 2003, The Crisis in Economics: The Post-Autistic Economics Movement. The First 600 Days, London: Routledge. Hodgson, Geofff 2001, How Economics Forgot History: The Problem of Historical Specificity in Social Science, London: Routledge. 2011, Sickonomics: Diagnoses and Remedies, Review of Social Economy, 69, 3: 35776. King, John E. 1979, Marx as an Historian of Economic Thought, History of Political Economy, 11, 3: 38294. Lee, Fred 2007, The Research Assessment Exercise, the State and the Dominance of Mainstream Economics in British Universities, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 31, 2: 30925. Lou, Francisco 1997, Turbulence in Economics: An Evolutionary Appraisal of Cycles and Complexity in Historical Processes, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Marx, Karl 1863, Theories of Surplus-Value, available at: <http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/ works/1863/theories-surplus-value/>. Milonakis, Dimitris and Ben Fine 2009, From Political Economy to Economics: Method, the Social and the Historical in the Evolution of Economic Theory, London: Routledge. Tabb, William K. 1999, Reconstructing Political Economy: The Great Divide in Economic Thought, London: Routledge.

You might also like

- Derivatives, Money, Finance and Imperialism: A Response To Bryan and RaffertyDocument20 pagesDerivatives, Money, Finance and Imperialism: A Response To Bryan and RaffertyHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- E.H. CARR-Socialism in One Country, 1924-26 Vol. 3 (A History of Soviet Russia) (1958) PDFDocument576 pagesE.H. CARR-Socialism in One Country, 1924-26 Vol. 3 (A History of Soviet Russia) (1958) PDFHyeonwoo Kim100% (1)

- On Lived Theory': An Interview WithDocument7 pagesOn Lived Theory': An Interview WithHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Cn7 Becker Ewald ConversationDocument35 pagesCn7 Becker Ewald ConversationDalila IngrandeNo ratings yet

- Perry Anderson On EuropeDocument18 pagesPerry Anderson On EuropeHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Derivatives, Money, Finance and Imperialism: A Response To Bryan and RaffertyDocument20 pagesDerivatives, Money, Finance and Imperialism: A Response To Bryan and RaffertyHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Seasons of Self-Delusion: Opium, Capitalism and The Financial MarketsDocument17 pagesSeasons of Self-Delusion: Opium, Capitalism and The Financial MarketsHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Imperialism and Capitalist Development in Marx's CapitalDocument31 pagesImperialism and Capitalist Development in Marx's CapitalHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Global Capitalist Crisis PDFDocument225 pagesGlobal Capitalist Crisis PDFHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Philippe Van Parijs - The Falling-Rate-Of Profit Theory of CrisisDocument16 pagesPhilippe Van Parijs - The Falling-Rate-Of Profit Theory of CrisisHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Razzismo Di Stato. Stati Uniti, Europa, ItaliaDocument14 pagesRazzismo Di Stato. Stati Uniti, Europa, ItaliaHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Fascism, Stalinism and The United FrontDocument290 pagesFascism, Stalinism and The United FrontHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Donny Gluckstein - The Paris Commune: A Revolution in DemocracyDocument128 pagesDonny Gluckstein - The Paris Commune: A Revolution in DemocracyDylan StillwoodNo ratings yet

- Science & Society (Vol. 76, No. 4)Document142 pagesScience & Society (Vol. 76, No. 4)Hyeonwoo Kim100% (1)

- Man's Worldly GoodsDocument240 pagesMan's Worldly GoodsHyeonwoo KimNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

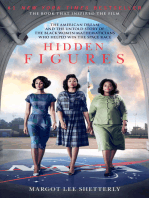

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Phase Domain Modelling of Frequency Dependent Transmission Lines by Means of An Arma ModelDocument11 pagesPhase Domain Modelling of Frequency Dependent Transmission Lines by Means of An Arma ModelMadhusudhan SrinivasanNo ratings yet

- Process Validation Statistical ConfidenceDocument31 pagesProcess Validation Statistical ConfidenceSally PujaNo ratings yet

- Space Gass 12 5 Help Manual PDFDocument841 pagesSpace Gass 12 5 Help Manual PDFNita NabanitaNo ratings yet

- Science 10 3.1 The CrustDocument14 pagesScience 10 3.1 The CrustマシロIzykNo ratings yet

- D5435 PDFDocument6 pagesD5435 PDFZamir Danilo Morera ForeroNo ratings yet

- Excellence Range DatasheetDocument2 pagesExcellence Range DatasheetMohamedYaser100% (1)

- Relay Testing Management SoftwareDocument10 pagesRelay Testing Management Softwarechichid2008No ratings yet

- S32 Design Studio 3.1: NXP SemiconductorsDocument9 pagesS32 Design Studio 3.1: NXP SemiconductorsThành Chu BáNo ratings yet

- Dimensioning GuidelinesDocument1 pageDimensioning GuidelinesNabeela TunisNo ratings yet

- Lenovo IdeaPad U350 UserGuide V1.0Document138 pagesLenovo IdeaPad U350 UserGuide V1.0Marc BengtssonNo ratings yet

- Studies On Diffusion Approach of MN Ions Onto Granular Activated CarbonDocument7 pagesStudies On Diffusion Approach of MN Ions Onto Granular Activated CarbonInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- Neptune Sign House AspectDocument80 pagesNeptune Sign House Aspectmesagirl94% (53)

- CIPP ModelDocument36 pagesCIPP ModelIghfir Rijal TaufiqyNo ratings yet

- 5.mpob - LeadershipDocument21 pages5.mpob - LeadershipChaitanya PillalaNo ratings yet

- C1 Reading 1Document2 pagesC1 Reading 1Alejandros BrosNo ratings yet

- User Manual: Swift S3Document97 pagesUser Manual: Swift S3smnguyenNo ratings yet

- CpE194 Lab Experiment # 1 - MTS-88 FamiliarizationDocument4 pagesCpE194 Lab Experiment # 1 - MTS-88 FamiliarizationLouieMurioNo ratings yet

- Reich Web ADocument34 pagesReich Web Ak1nj3No ratings yet

- Dasha TransitDocument43 pagesDasha Transitvishwanath100% (2)

- Structural Testing Facilities at University of AlbertaDocument10 pagesStructural Testing Facilities at University of AlbertaCarlos AcnNo ratings yet

- Fault Tree AnalysisDocument5 pagesFault Tree AnalysisKrishna Kumar0% (1)

- 10 1016@j Ultras 2016 09 002Document11 pages10 1016@j Ultras 2016 09 002Ismahene SmahenoNo ratings yet

- Countable and Uncountable Nouns Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesCountable and Uncountable Nouns Lesson PlanAndrea Tamas100% (2)

- IS BIOCLIMATIC ARCHITECTURE A NEW STYLE OF DESIGNDocument5 pagesIS BIOCLIMATIC ARCHITECTURE A NEW STYLE OF DESIGNJorge DávilaNo ratings yet

- Cost of Litigation Report (2015)Document17 pagesCost of Litigation Report (2015)GlennKesslerWPNo ratings yet

- Tutor Marked Assignment (TMA) SR Secondary 2018 19Document98 pagesTutor Marked Assignment (TMA) SR Secondary 2018 19kanna2750% (1)

- Vocabulary Prefixes ExercisesDocument2 pagesVocabulary Prefixes ExercisesMarina García CarrascoNo ratings yet

- Stereotype Threat Widens Achievement GapDocument2 pagesStereotype Threat Widens Achievement GapJoeNo ratings yet

- QQQ - Pureyr2 - Chapter 3 - Sequences & Series (V2) : Total Marks: 42Document4 pagesQQQ - Pureyr2 - Chapter 3 - Sequences & Series (V2) : Total Marks: 42Medical ReviewNo ratings yet

- Blank Character StatsDocument19 pagesBlank Character Stats0114paolNo ratings yet