Professional Documents

Culture Documents

We Need Not Think Alike - The Basis For Disagreements 2013-01-27

Uploaded by

Dana Reynolds IIIOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

We Need Not Think Alike - The Basis For Disagreements 2013-01-27

Uploaded by

Dana Reynolds IIICopyright:

Available Formats

We Need Not Think Alike-The Basis for Disagreements

2013-01-27

There is a saying attributed to our spiritual forebear, Francis Dvid, the religious reformer in 16th century Transylvania. The saying, we need not think alike to love alike, is probably something that Dvid never said. Nevertheless, we Unitarian Universalists love this saying! It does not matter to me whether or not Dvid ever said, we need not think alike to love alike, because this phrase says a lot about who we are as Unitarian Universalists. Michael Servetus and Francis Dvid were the two theologians in the 16th century from whom we trace our religious heritage. It was the martyrdom of Servetus and the preaching and administration of Dvid that was the embodiment of this phrase and heralded the beginning of religious toleration in Europe. I think there are a couple of reasons why we like this phrase, even if we cant attribute it to one of our heroes, like Francis Dvid. Our second Unitarian Universalist principle affirms and promotes compassion in human relations. There is nothing in that principle that says that there must be agreement about thinking or ideas before there can be compassion for others. And notice that this principle talks about compassion, rather than about love in the human relations. Back on September 23, I talked about the possibility, as taught by the Dalai Lama, of having compassion for others as a trait we can cultivate and I shared with you some ways we can learn to do that and to do it better. On the other hand, I cannot tell you how to have love for someone you currently do not love. Cultivating compassion, as I said in that sermon, is an activity in which we can engage that might in fact, lead toward loving another person. Cultivating compassion is something we can practice doing, meaning that our second principle, to affirm and promote compassion in human relations, is something that is possible. Another reason we like this saying, we need not think alike to love alike, is that it concurs with a portion of our third principle, which affirms and promotes the acceptance of one another. This principle means we accept others for whoever they are, whomever they love, whatever they are, and wherever they are on their journey. It does not matter that we think alike for such acceptance to take place. So, our compassion for, and our acceptance of others is not at all dependent upon the mutual agreement of ideas, propositions, or any other output of thinking.

We Need Not Think Alike-The Basis for Disagreements

2013-01-27

Indeed, if professor Ronald Heifetz1 is correct, we dont even agree with ourselves internally much of the time! Heifetz says that our entire lives we have been wrestling with our internalized voices of values, beliefs, and norms, deciding which ones to give our assent to and which ones to ignore. Each of us has an ongoing, internal debate about a lot of things. The debates within us give us the room to choose, Heifetz tells us. Growing up, I have memories of my mother and father not being in agreement with each other over something I knew would have at least an indirect impact on me. I dont remember what the something was, but I do remember the realization I would need to proceed cautiously, and avoid taking sides, if I could. I am guessing that many of us would recognize these different voices and mixed messages we received while we were growing up. Not only is it difficult to come to an agreement with others, coming to agreement within ourselves over differing points of view can also be difficult. Two weeks ago I talked about ideas, where they come from and how we assess them. I quoted John Locke who said that an idea stands for whatsoever is the object of the understanding when a person thinks. We also saw how ideas or thinking builds upon the ideas or thinking that came before. In addition, I dont think its much of a mental leap to suggest that thinking, ideas, or concepts, change over time. For example, humans used to think that the earth was only a few thousand years old. That thinking is no longer an accurate reflection of reality, except for radical religious zealots and a few members of the US House of Representatives! It has been replaced by sophisticated carbon-dating methods, which measured the decay in organic compounds of the radioisotope carbon-14. In my own life, I used to think that God was a distinct being, with all of the contradictions in the characteristics and attributes portrayed in the Hebrew and in the Christian Bibles. I stopped thinking in this way, because that idea no longer was working for the circumstances in my life. I now think the contradictions in those accounts, often intended to be so, were metaphors, pointing toward values and meanings, especially for the times in which they were written. I do not have a problem with anyone who thinks differently. I will not let that kind of thinking be an obstacle between myself and others. Indeed, two of my

Leadership W ithout Easy Answers, Ronald Heifetz, p. 62

We Need Not Think Alike-The Basis for Disagreements

2013-01-27

three children hold some version of this thinking about God today. And besides, there is no data one way or the other. One could make a case that God exists or that God does not exist, depending on the criteria used, yet it would be speculation at best. I happen to think that it is not particularly relevant anyway and besides, I resonate more closely with the metaphor, the interdependent web of all existence. It would be possible to play a word game on whether the interdependent web of all existence shared any of the characteristics of the traditional view of God. Human thinking on this subject of God is evolving all the time. The idea of a single divine being is relatively new. During most of our human history, written or not, the divine consisted of many gods and goddesses, each with their own portfolios of attributes and abilities. A significant advantage to a polytheistic world view is the greater acceptance of differences in religious belief. For the English word, God, has its original usage in meaning, that which is invoked, or called upon. People, myself included, invoke unseen, unknown powers, like the names of the gods and goddesses, all the time. For example, have you ever forgotten someones name, a person you know? I say to myself, I know that I know that person I see in a social gathering, but his or her name is not coming to me. Quick! They are headed my way! Where is the name? This is one example in many that we encounter all the time. It is when we come to the end of our known human resources, we call upon that which is unknown. It is risky to criticize a thought, a concept, or an idea. There are two important reasons for this. First, we are usually going to criticize someone elses thinking or ideas. The risk is that to criticize someones idea might be received as a criticism of the person holding such an idea. We cannot know how closely someone might identify themselves with an idea. John Calvin, it is clear, personally identified with the idea of the Trinity, but Michael Servetus could not have known this was the case. This is when disagreements escalate into conflicts between people. The second risk comes from our own thinking or ideas. If we do not examine them, criticize them, or analyze them, which can be hard to do, I know, we too might identify ourselves too closely with a thought or an idea. The process Heifetz wrote about -- internalizing the values, beliefs, norms, etc., of our parents, teachers and others, yet at the same time, detaching those things from the actual persons -- is something we must do for our own thoughts, values, and so on. Otherwise, we will become overly identified with a thought, a value, or an idea, which could lead to disappointment if new altering realities set in. Or, a criticism

3

We Need Not Think Alike-The Basis for Disagreements

2013-01-27

from another person will then be misunderstood as a personal criticism, rather than of that thought, value, or idea. Charlotte Kasl2 highly recommends dealing with these sorts of conflicts early on. She says it is best to name what is going on and therefore bring the differences to the surface. The differences are about the ideas, the differences in thinking, not in the differences between personalities. Our personalities are not bound to thoughts or ideas, because they are separate. We need not think alike to love alike. This has implications for Unitarian Universalism and our creedless faith tradition. Our story is a complicated, but fascinating one. [Include Our UU Story promotion]. The Christian church has had creeds, of one kind or another, since the fourth century. Statements of creeds are those thoughts and ideas that define what a faith tradition is and what it isnt. Unitarians and Universalists have flirted with, but succeeded in avoiding outright creeds. Nevertheless, definitions of what Unitarian Universalism is like, still exist. And definitions are products of thinking. Yet these definitions can also be assumptions, and we all know the dangers when we assume. A case in point, many assume that all Unitarian Universalists are Democrats, or members of the Democratic Party. And they would be, what I like to call, wrong. Now, it is true that I happen to be a Democrat. And other than that acknowledgment, I have tried to keep my partisan position out of the church. Of course I have not been perfect at this, but I know that getting better at living out religious values is a possibility for all of us. I know full well that had I grown up in the American South, instead of the Midwest, I would not have been a Democrat, or what was called in my day, a Dixiecrat. I could not have put up with the racism that was part of that world view. For more than 100 years in the South, no one was a Republican simply because that was the party of Lincoln and Lincoln had freed the slaves. Elliot Richardson was the 69th Attorney General of the United States, appointed by Pres. Nixon. Richardson was from Boston and was a Republican and a Unitarian. He was known during the Watergate era as standing up to Nixon, by refusing to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox. Many applauded his heroic effort.

A Hom e for the Heart, Charlotte Sophia Kasl, p.55

We Need Not Think Alike-The Basis for Disagreements

2013-01-27

William Cohen was the secretary of defense under Pres. Bill Clinton. Prior to that, he was a Republican United States senator from Maine. William Cohen is a Unitarian and helped President Clinton achieve his goal of having a bipartisan cabinet. We cannot assume. We cannot stereotype. We cannot allow thoughts to morph into ideas without examination. For if we do, those unexamined ideas will morph into beliefs that are like blinders, as Sophia Lyons Fahs tells us, shutting off the power to choose ones own direction. We do not need to think alike to love alike. Let me close with a quotation from blogger, Lisa Williams, entitled, Us and Them.3 There is no Them, there is only Us. Some of Us think this or some of Us think that, but we are all Us.

Us and Them : A Blog Conversation Survival Guide, Lisa W illiam s, SXSW 2006.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- E MudhraDownload HardDocument17 pagesE MudhraDownload HardVivek RajanNo ratings yet

- Test ScienceDocument2 pagesTest Sciencejam syNo ratings yet

- Module 1: Overview of Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA)Document37 pagesModule 1: Overview of Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA)PriyaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Exercises With AnswerDocument5 pagesChapter 13 Exercises With AnswerTabitha HowardNo ratings yet

- g6 - AFA - Q1 - Module 6 - Week 6 FOR TEACHERDocument23 pagesg6 - AFA - Q1 - Module 6 - Week 6 FOR TEACHERPrincess Nicole LugtuNo ratings yet

- Hima OPC Server ManualDocument36 pagesHima OPC Server ManualAshkan Khajouie100% (3)

- (123doc) - Toefl-Reading-Comprehension-Test-41Document8 pages(123doc) - Toefl-Reading-Comprehension-Test-41Steve XNo ratings yet

- Revenue and Expenditure AuditDocument38 pagesRevenue and Expenditure AuditPavitra MohanNo ratings yet

- ISBN Safe Work Method Statements 2022 03Document8 pagesISBN Safe Work Method Statements 2022 03Tamo Kim ChowNo ratings yet

- Radiation Safety Densitometer Baker PDFDocument4 pagesRadiation Safety Densitometer Baker PDFLenis CeronNo ratings yet

- LM74680 Fasson® Fastrans NG Synthetic PE (ST) / S-2050/ CK40Document2 pagesLM74680 Fasson® Fastrans NG Synthetic PE (ST) / S-2050/ CK40Nishant JhaNo ratings yet

- IKEA SHANGHAI Case StudyDocument5 pagesIKEA SHANGHAI Case StudyXimo NetteNo ratings yet

- Leak Detection ReportDocument29 pagesLeak Detection ReportAnnMarie KathleenNo ratings yet

- Leigh Shawntel J. Nitro Bsmt-1A Biostatistics Quiz No. 3Document6 pagesLeigh Shawntel J. Nitro Bsmt-1A Biostatistics Quiz No. 3Lue SolesNo ratings yet

- Pt3 English Module 2018Document63 pagesPt3 English Module 2018Annie Abdul Rahman50% (4)

- DPSD ProjectDocument30 pagesDPSD ProjectSri NidhiNo ratings yet

- Lithuania DalinaDocument16 pagesLithuania DalinaStunt BackNo ratings yet

- Broken BondsDocument20 pagesBroken Bondsapi-316744816No ratings yet

- Corrosion Fatigue Phenomena Learned From Failure AnalysisDocument10 pagesCorrosion Fatigue Phenomena Learned From Failure AnalysisDavid Jose Velandia MunozNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of Coustomer Satisfaction in Demat Account At: A Summer Training ReportDocument110 pagesA Case Study of Coustomer Satisfaction in Demat Account At: A Summer Training ReportDeepak SinghalNo ratings yet

- Pavement Design1Document57 pagesPavement Design1Mobin AhmadNo ratings yet

- Report On GDP of Top 6 Countries.: Submitted To: Prof. Sunil MadanDocument5 pagesReport On GDP of Top 6 Countries.: Submitted To: Prof. Sunil MadanAbdullah JamalNo ratings yet

- Negotiating Skills Negotiating Skills: To Provide You With The Skills To Plan & Implement Successful NegotiationDocument32 pagesNegotiating Skills Negotiating Skills: To Provide You With The Skills To Plan & Implement Successful NegotiationKanimozhi.SNo ratings yet

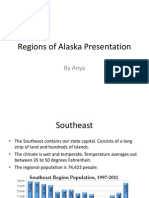

- Regions of Alaska PresentationDocument15 pagesRegions of Alaska Presentationapi-260890532No ratings yet

- Lecturenotes Data MiningDocument23 pagesLecturenotes Data Miningtanyah LloydNo ratings yet

- Pivot TableDocument19 pagesPivot TablePrince AroraNo ratings yet

- DP 2 Human IngenuityDocument8 pagesDP 2 Human Ingenuityamacodoudiouf02No ratings yet

- Syllabus DresserDocument2 pagesSyllabus DresserVikash Aggarwal50% (2)

- Chapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDocument63 pagesChapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDr. Shuva GhoshNo ratings yet

- Monkey Says, Monkey Does Security andDocument11 pagesMonkey Says, Monkey Does Security andNudeNo ratings yet