Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Protection of State Information Bill Passed by Parliament Call For Constitutional Court Review by Dr. Raymond Louw, Vice President of SA PEN

Uploaded by

SA BooksOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Protection of State Information Bill Passed by Parliament Call For Constitutional Court Review by Dr. Raymond Louw, Vice President of SA PEN

Uploaded by

SA BooksCopyright:

Available Formats

Protection of State Information Bill passed by Parliament; call for Constitutional Court review By Dr.

Raymond Louw, Vice President of SA PEN, 30/04/2013 After five years of debate, South Africas Protection of State Information Bill, or secrecy bill as it was dubbed, the legislation passed through the final stage of the Parliamentary process on April 26 with 190 members voting in favour, 75 voting against and one member abstaining. A total of 134 members, of which 34 were members of the ruling party, the African National Congress, were absent. The next step is for President Jacob Zuma to sign the bill into law or if he has doubts about its constitutionality, to return it to the National Assembly for review. Alternatively, he can refer it directly to the Constitutional Court to establish its constitutionality. If he signs it into law the opposition parties have the option of referring it to the court if they can muster 134 votes, a third of the houses 400 members. That will be a hard task because opposition members in the house total 136 and not all of them may vote for such a move and the chances of ANC members siding with the vote are slim. Several civil society organisations such as the South African National Editors Forum, the Freedom of Expression Institute and the Right2Know campaign who have strongly opposed the bill have declared their intention to refer it to the Constitutional Court if the parliamentary processes do not succeed. The process open to them is to apply to the court directly. Their determination suggests that ultimately the bill will land up before the court and several lawyers in contrast to the governments legal advisors believe it will fail the constitutional test. The lengthy processes to which the bill has been subject -- some 800 changes to the text were made -- has resulted in many improvements, but the bill remains under attack because the amendments have not gone far enough and there are still some very objectionable features. The major criticism remains a failure to include a public interest defence for contravening a provision of the Bill prohibiting the publication of classified information that should be in the public domain in the public interest. Lack of this protection could be harmful to whistleblowers, journalists and members of the public. Other broad criticisms of the bill are that the definitions and classification procedures and applications are too broad and not strictly limited to national security which the bill states is the purpose; the scope for classification to be applied includes cabinet ministers and heads of government departments and other organs of state which make application showing good cause for such power to be extended to them; the wording of some sections of the bill is confusing and contradictory and open to misinterpretation; and the excessive powers given to the Minister of State Security whose role extends beyond the scope of policy making and could result in political interference in the classification of information. Another complaint is the manner in which the drafters of the bill have ignored the principles for classification of official secrets outlined in the Johannesburg Principles drawn up by a group of senior lawyers and experts in international and constitutional law, national security and human rights who in 1995 gathered in a country lodge north of Johannesburg to compose them into a document which has been endorsed by the United Nations Commission on 1|Page

Human Rights. The conference was organised by Article 19 in collaboration with the Centre for Applied Legal Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. One of the broad descriptions of subject areas that give rise to concerns about the manner in which a very wide range of information can be classified is contained in the definition of national security. This includes the protection of the people and territorial integrity of the Republic against the exposure of economic, scientific or technological secrets vital to the Republic. The manner in which authority to classify information is extended far beyond the confines of the security establishment, despite a clause which states that secrecy is justifiable only when it is necessary to protect the national security, emerges in another clause which states that the powers of classification, reclassification and declassification apply to the cabinet, security, defence and police services and to any organ of state or part thereof that makes application to the Minister of State Security. A head of an organ of state may delegate, in writing, the authority to classify state information to a staff member at a sufficiently senior level without spelling the level of seniority. Potential ministerial involvement in classification is illustrated by a clause which says that if there is significant doubt as to whether state information requires protection, the matter must be referred to the relevant minister for a decision. While having made the point that protection of national security is the only justifiable reason for secrecy, another clause dealing with the principles that underpin the legislation ``and inform its interpretation and implementation states that the protection and classification of certain state information is however vital to save lives, to enhance and to protect the freedom and security of persons, bring criminals to justice, protect the national security and to engage in effective government and diplomacy. When information is categorised as classified, all individual items of information that fall within that classified category are deemed to be classified. A classification review panel will assess and hear appeals against classifications but the criticisms are that the minister has a say in the composition of the panel and also in how it conducts its affairs. Another area where the minister may exercise substantial powers to interfere with the classification processes and introduce undesirable political considerations is in the promulgation of regulations. The penalties that can be incurred are severe and range from three to 25 years imprisonment. The most severe penalty is imprisonment of between 15 and 25 years for a person who unlawfully and intentionally communicates, delivers or makes available state information classified top secret which the person knows or ought reasonably to have known would directly or indirectly benefit a foreign state; or who unlawfully and intentionally makes, obtains, collects, captures or copies a record containing state information classified top secret which the person knows or ought reasonably to have known would directly or indirectly benefit a foreign state. Lesser prison sentences apply to similar offences involving information classified secret or confidential. Conviction on the basis that a person ought reasonably to have known would directly or indirectly benefit a foreign state is questionable. Also questionable are the restrictive measures imposed on judicial offices to conduct court hearings in camera because classified information may be produced during the hearing.

2|Page

A clause which will have a chilling effect on journalists states that a person in possession of a classified record knowing that it has been unlawfully communicated, delivered or made available must hand over the document to the police, the intelligence service or the state department that classified the information. Failure to do so carries a jail sentence of five years. It is uncertain whether having handed over the document the person would be charged with possession. If a reporter is involved and they are frequently recipients of such communications -- he or she may also be confronted with the ethical question of whether to disclose the identity of the person who gave the document.

3|Page

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 50 Years of South African Rugby: A Free Sunday Times EbookDocument134 pages50 Years of South African Rugby: A Free Sunday Times EbookSA Books100% (3)

- Lambino Vs Comelec Case Digest G R No 174153Document1 pageLambino Vs Comelec Case Digest G R No 174153Aljay Labuga83% (6)

- Anama v. Citibank G.R. No. 192048Document8 pagesAnama v. Citibank G.R. No. 192048Christian ALNo ratings yet

- Bolos, Jr. v. Commission On ElectionsDocument2 pagesBolos, Jr. v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Go vs. Republic, G.R. No. 202809, July 2, 2014Document1 pageGo vs. Republic, G.R. No. 202809, July 2, 2014Pre AvanzNo ratings yet

- US v. BarriasDocument2 pagesUS v. BarriasMaria AnalynNo ratings yet

- Free Ebook: Braai RecipesDocument16 pagesFree Ebook: Braai RecipesSA Books100% (1)

- Chua Vs Civil Service CommissionDocument2 pagesChua Vs Civil Service CommissionFreiah100% (1)

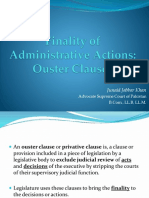

- Finality of Administrative ActionsDocument19 pagesFinality of Administrative ActionsdanishzakirNo ratings yet

- Tan Vs Macapagal - Garcia Vs BOIDocument5 pagesTan Vs Macapagal - Garcia Vs BOIKristell FerrerNo ratings yet

- 002 Tolentino V COMELECDocument2 pages002 Tolentino V COMELECyousirneighmNo ratings yet

- Caram Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesCaram Vs ComelechappymabeeNo ratings yet

- San Miguel vs. Layoc Jr. GR 149640 Oct. 19, 2007Document4 pagesSan Miguel vs. Layoc Jr. GR 149640 Oct. 19, 2007Ran Basada-De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 2016 Kimberley Book FairDocument3 pages2016 Kimberley Book FairSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Introductin To Protest Nation: The Right To Protest in South AfricaDocument23 pagesIntroductin To Protest Nation: The Right To Protest in South AfricaSA BooksNo ratings yet

- An Excerpt From Green in Black-and-White Times: Conversations With Douglas LivingstoneDocument27 pagesAn Excerpt From Green in Black-and-White Times: Conversations With Douglas LivingstoneSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 2016 Abantu Book Festival ProgrammeDocument16 pages2016 Abantu Book Festival ProgrammeSA Books100% (1)

- 2016 Open Book ProgrammeDocument7 pages2016 Open Book ProgrammeSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Flame in The Snow Extract 1 MayApril1963Document7 pagesFlame in The Snow Extract 1 MayApril1963SA BooksNo ratings yet

- 2016 Puku Story Festival Isixhosa ProgrammeDocument6 pages2016 Puku Story Festival Isixhosa ProgrammeSA Books0% (1)

- Remembering Joe SlovoDocument1 pageRemembering Joe SlovoSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Excerpt Jabu Goes To Joburg, The Fotonovela Featured in The Latest Edition of Chimurenga's CronicDocument6 pagesExcerpt Jabu Goes To Joburg, The Fotonovela Featured in The Latest Edition of Chimurenga's CronicSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 2016 Puku Story Festival English ProgrammeDocument6 pages2016 Puku Story Festival English ProgrammeSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Prologue Jan Smuts: Unafraid of GreatnessDocument16 pagesPrologue Jan Smuts: Unafraid of GreatnessSA Books0% (1)

- David Bowie's Space Oddity, The Children's BookDocument21 pagesDavid Bowie's Space Oddity, The Children's BookSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From Back To Angola by Paul MorrisDocument14 pagesExcerpt From Back To Angola by Paul MorrisSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Remembering Joe SlovoDocument1 pageRemembering Joe SlovoSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Remembering Joe SlovoDocument1 pageRemembering Joe SlovoSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Luka Jantjie: A Publisher's View of A Highly Illustrated Historical BiographyDocument39 pagesLuka Jantjie: A Publisher's View of A Highly Illustrated Historical BiographySA BooksNo ratings yet

- Dangerous Snakes of Southern AfricaDocument1 pageDangerous Snakes of Southern AfricaSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From Recipes For Love and Murder: A Tannie Maria Mystery by Sally AndrewDocument11 pagesExcerpt From Recipes For Love and Murder: A Tannie Maria Mystery by Sally AndrewSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 2015 ParkWords ProgrammeDocument2 pages2015 ParkWords ProgrammeSA BooksNo ratings yet

- African Flavour Books Celebrates Zukiswa WannerDocument2 pagesAfrican Flavour Books Celebrates Zukiswa WannerSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 55-People Vs Castillo-Motion To QuashDocument1 page55-People Vs Castillo-Motion To QuashJeff JuansonNo ratings yet

- Jaban Vs Cebu CityDocument1 pageJaban Vs Cebu CityAgnes LintaoNo ratings yet

- Memorial On Behalf of PetitionerDocument22 pagesMemorial On Behalf of PetitionerKoshalNo ratings yet

- Caver v. Michigan Department of Corrections Et Al - Document No. 3Document3 pagesCaver v. Michigan Department of Corrections Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Begun and Held in Metro Manila, On Monday, The Twenty-Fifth Day of July, Two Thousand SixteenDocument3 pagesBegun and Held in Metro Manila, On Monday, The Twenty-Fifth Day of July, Two Thousand SixteenMarky OlorvidaNo ratings yet

- Francisco v. HOR DigestDocument6 pagesFrancisco v. HOR DigestKaren PanisalesNo ratings yet

- Mark Anthony Zabal, Thiting Estoso Jacosalem, and Odon S. Bandiola v. President Rodrigo Duterte, Salvador Medildea, and Eduardo Año, G.R No. 238467, February 12, 2019.Document1 pageMark Anthony Zabal, Thiting Estoso Jacosalem, and Odon S. Bandiola v. President Rodrigo Duterte, Salvador Medildea, and Eduardo Año, G.R No. 238467, February 12, 2019.christopher1julian1aNo ratings yet

- Ilusorio vs. BildnerDocument8 pagesIlusorio vs. BildnerQueenie SabladaNo ratings yet

- Major Sources of Indian ConstitutionDocument2 pagesMajor Sources of Indian ConstitutionadamNo ratings yet

- Vijay Prakash Singh Vs Union of India Others On 27 July 2018Document4 pagesVijay Prakash Singh Vs Union of India Others On 27 July 2018Prateek RaiNo ratings yet

- PPG LESSON 3 (SLM) - Braches of Natl GovtDocument35 pagesPPG LESSON 3 (SLM) - Braches of Natl GovtjumawanelvieNo ratings yet

- Republic Act No. 10707Document1 pageRepublic Act No. 10707Emrico CabahugNo ratings yet

- CUSTODYDocument2 pagesCUSTODYCJ MillenaNo ratings yet

- Peter Maassen Selected As Chief Justice of Alaska Supreme CourtDocument1 pagePeter Maassen Selected As Chief Justice of Alaska Supreme CourtAlaska's News SourceNo ratings yet

- Defendant's Motions For Summary JudgementDocument35 pagesDefendant's Motions For Summary JudgementRay Still0% (1)

- Caselist Quasidelicts2Document2 pagesCaselist Quasidelicts2Fender BoyangNo ratings yet

- Methods of Acquiring and Losing of Citizenship Under Indian Citizenship ActDocument5 pagesMethods of Acquiring and Losing of Citizenship Under Indian Citizenship ActRiya RoyNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Save The Supreme Court Judicial Independence UK 15143Document2 pagesIn The Matter of Save The Supreme Court Judicial Independence UK 15143Gjenerrick Carlo MateoNo ratings yet

- Mayors CourtDocument12 pagesMayors CourtAayush KumarNo ratings yet