Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Complete Pascal Adding Machine Report (Minus Energy Transfer Diagram)

Uploaded by

XzeleousCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Complete Pascal Adding Machine Report (Minus Energy Transfer Diagram)

Uploaded by

XzeleousCopyright:

Available Formats

Pascal’s Adding machine was created to serve the purpose

of adding and subtracting up to 8 digit numbers, along with

multiplication and division; however, multiplication and division

functions were complicated and often took a very long time. The

operation of the machine would consist of turning dials that

rotated a spool of paper underneath the dial, which in turn would

turn the paper, changing the number in the window at the top of

the machine. The dials had interlocking gears, so that when the

first dial, representing one of the place values in math, was

turned all the way to 9 and then further back to zero, the

following gear would automatically rotate to the number 1. This

provided easy operations of addition and subtraction to

accountants and users, as to add they turned the dials right, and

subtraction to the left. Multiplication and division was achieved

by a series of complicated additions or subtractions, often

making such functions cumbersome. The machine was created

for and used by accountants, such as Pascal’s father. The

machine was intended to make mathematical functions easier

and more accurate. Pascal’s adding machine was created and

marketed in 1642, when the first machine was given to his father.

One of the adding machines even made its way to King Louis XIV!

However, the machine never made Pascal rich.

Pascal’s Adding Machine affected the world in

numerous ways, and has even inspired modern day

tools. Pascal's principal of interlocking wheels

remained important to the operation of most adding

machines for the next 300 years. The machine also

got Pascal wide praise, and is attributed to his

current fame. Parts of Pascal’s design were seen in

newer manual adding calculators until the invention

of digital adding devices. The device affected history

by becoming the first adding device ever created.

The way the interlocking gears worked inside the

machine is still being used today to move many

gears at the same time in modern machinery. Modern

computers have even felt the influence from Pascal’s

historical achievement. A popular programming

language that uses math as instructions has been

named after Pascal. This shows that even modern

devices would not be the same without inspiration

from Pascal’s early device, along with the world and

its people.

Blaise Pascal was Etienne Pascal’s only son. He

was born in Clermont, France, where his mother died when

he was three. Him and his family moved to Paris and finally

to Rouen, Upper Normandy, where Pascal invented his

adding machine to help his father, a tax collector. Blaise

encountered many difficulties with his invention. Most of

these could be blamed on the French currency system of the

time, in which an odd set of multiples were used (Ex. 20 sols

in a livre and 12 deniers in a sol.). Many technical problems

were encountered as Pascal had to develop his own gear

system for the device. He also had to account for the use of

the Livre piece of currency, which complicated the design as

he had to work with divisions of 240 rather then 100. What is

even more amazing, but also gave Pascal even more of a

challenge, is that he did not work with a collaborator.

Unfortunately, Pascal’s device was a marketing disaster.

Fifty prototype devices were created, and very few were

sold. The adding machine was discontinued in 1652, after a

very short production run. Blaise Pascal then turned himself

towards science and physics, and is famed for proving

vacuum existed. He also became very religious during his

short life. Pascal died at the age of 39 in intense pain after a

growth in his stomach spread to the brain.

Works Cited

Bettman. Pascal's Adding Machine. Bettmann Standard RM. CORBIS. 18 Apr. 2009

<http://pro.corbis.com/images/F3868.jpg?size=67&uid=309dc746-c9bc-4c26-

b411-9d028fbca22a>.

Champaigne, Philippe. Blaise Pascal (1623-62). Baroque Men Portraits. 1st Art Gallery.

18 Apr. 2009 <https://www.1st-art-gallery.com/Philippe-De-Champaigne/Blaise-

Pascal-(1623-62).html>.

A, Devaux. The adding machine of Blaise Pascal. The First Calculators. The First

Calculators. 18 Apr. 2009 <http://calculmecanique.chez-

alice.fr/anglais/first_calculators.htm>.

A, Happy. Adding Machine. 25 Nov. 2006. Paris (Set). Flickr. 25 Nov. 2006. 18 Apr.

2009 <http://www.flickr.com/photos/28391363@N00/305917078>.

Hayes, Frank. "Pascaline." The history of computing project. 8 May 2007. 18 Apr. 2009

<http://www.thocp.net/hardware/pascaline.htm>.

"Pascal's Adding Machine." Oracle ThinkQuest Library. 18 Apr. 2009

<http://library.thinkquest.org/J002036F/pascal's_adding_machine.htm>.

Phillips, Johnathan. "Pascal's Adding Machine." AgentSheets. University of Colorado,

Boulder. 18 Apr. 2009 <http://www.agentsheets.com/Applets/pascals-adding-

machine/readme.html>.

Tomecek, Stehphen M., and Dan Stuckenschneider. What a Great Idea (Inventions That

Changed the World). New York: Scholastic Inc., 2003.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

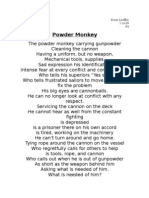

- Civil War Poem: Powder MonkeyDocument1 pageCivil War Poem: Powder MonkeyXzeleous100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 1863 New York Draft Riots Eyewitness AccountDocument3 pages1863 New York Draft Riots Eyewitness AccountXzeleousNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Civil War Irregular Rhyme Scheme PoemDocument1 pageCivil War Irregular Rhyme Scheme PoemXzeleousNo ratings yet

- Tungsten HaikuDocument1 pageTungsten HaikuXzeleousNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Prepositions and Prepositional Phrases WorksheetDocument2 pagesPrepositions and Prepositional Phrases WorksheetXzeleous100% (8)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Salem Witch Trials Podcast ScriptDocument2 pagesSalem Witch Trials Podcast ScriptXzeleousNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Paiute Report Works CitedDocument1 pagePaiute Report Works CitedXzeleous100% (2)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Process PlanningDocument2 pagesProcess Planningsujit kcNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Tech Manual ZX200 PDFDocument407 pagesTech Manual ZX200 PDFJUNA RUSANDI S100% (4)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- CAM GTU Study Material E-Notes Unit-6 08052021103558AMDocument29 pagesCAM GTU Study Material E-Notes Unit-6 08052021103558AMparth bhardwajNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Pedal Operated Water Pumping SystemDocument33 pagesPedal Operated Water Pumping Systemchristin9193% (15)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Fractal RobotDocument13 pagesFractal RobotKing Chetan100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Pressure Sensitive Safety Edge System ManualDocument24 pagesPressure Sensitive Safety Edge System ManualJehiel AlvarezNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Maintenance Group AssignmentDocument20 pagesMaintenance Group Assignmentdawit gashuNo ratings yet

- Gujarat Technological University: W.E.F. AY 2018-19Document2 pagesGujarat Technological University: W.E.F. AY 2018-19Er Umesh ThoriyaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Centrifugal PumpDocument44 pagesCentrifugal PumpAmishaan KharbandaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of CMR 1957&2017Document203 pagesComparison of CMR 1957&2017PuBg FreakNo ratings yet

- Agri ProcessDocument63 pagesAgri ProcessAlfredo Jr FortuNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Me6401 Kom PDFDocument131 pagesMe6401 Kom PDFRichard JoshNo ratings yet

- 99ebook Com Msg00388 PDFDocument15 pages99ebook Com Msg00388 PDFM Sarmad KhanNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Estacion HAWE Compacta HKDocument26 pagesEstacion HAWE Compacta HKJasierNo ratings yet

- Advanced Manufacturing Systems PDFDocument27 pagesAdvanced Manufacturing Systems PDFkrishnaNo ratings yet

- Robotics QP Sum19Document1 pageRobotics QP Sum19nandkishor joshiNo ratings yet

- Sensor's BrochureDocument18 pagesSensor's BrochureStandards IndiaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Terex Finlay I-110 Impact Crusher PDFDocument4 pagesTerex Finlay I-110 Impact Crusher PDFeaglego00No ratings yet

- Vol.2 General Specification of ZJ50D RigDocument57 pagesVol.2 General Specification of ZJ50D Rigwaleed100% (1)

- Weft MasterDocument20 pagesWeft MasterZulfikar Ari PrkzNo ratings yet

- RPS Spare CatalogDocument25 pagesRPS Spare Catalogसुरेश चंद Suresh ChandNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Motorized Treadmills: Standard Specification ForDocument8 pagesMotorized Treadmills: Standard Specification ForpechugonisNo ratings yet

- Chint YblxDocument41 pagesChint YblxJuan David Melián CruzNo ratings yet

- General Instruction Manual - Bosch RexrothDocument64 pagesGeneral Instruction Manual - Bosch Rexrothvalgorunescu@hotmail.comNo ratings yet

- Syllabus: ME 104, Mechanical Systems Design - Winter 2021Document6 pagesSyllabus: ME 104, Mechanical Systems Design - Winter 2021د.محمد كسابNo ratings yet

- The Catalog of TCN Vending MachineDocument74 pagesThe Catalog of TCN Vending MachineJihad AzamiNo ratings yet

- Bsuresh Resume CV MergedDocument8 pagesBsuresh Resume CV Mergedapi-341918518No ratings yet

- 3-1 RA 8495 Article IDocument27 pages3-1 RA 8495 Article ICollano M. Noel RogieNo ratings yet

- Reinventing Organizations Illustrated (160618) PDFDocument173 pagesReinventing Organizations Illustrated (160618) PDFLeandro Ruiz100% (2)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)