Professional Documents

Culture Documents

98 Hydrolosis of Vegetable Oils

Uploaded by

Syahrul RamadhanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

98 Hydrolosis of Vegetable Oils

Uploaded by

Syahrul RamadhanCopyright:

Available Formats

Hydrolysisof VegetableOils in Sub- and Supercritical Water

Russell L. Holliday, Jerry W. King, and Gary R. List Food Quality& Safety ResearchUnit, NationalCenterfor Agricultural Utilization Research,Agricultural ResearchService/ USDA, 1815 N. UniversityStreet, Peoria,Illinois 61604

INDUSTRIAL& ENGINEERING CHEMISTRY RESEZiRCH

Reprinted from Volume 36, Number 3, Pages 932-935

932

Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997,36,

932-935

RESEARCH NOTES

Hydrolysis of Vegetable

Russell L. Holliday,*

Oils in Sub- and Supercritical

Jerry W. King, and Gary R. List

Water

Food Quality & Safety Research Unit, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Agricultural Research Service/ USDA, 1815 N. University Street, Peoria, Illinois 61604

Water, in its subcritical state, can be used as both a solvent and reactant for the hydrolysis of In this study, soybean, linseed, and coconut oils were successfully and reproducibly triglycerides. hydrolyzed to free fatty acids with water at a density of 0.7 g/mL and temperatures of 260-280 C. Under these conditions the reaction proceeds quickly, with conversion of greater than 97% after 15-20 min. Some geometric isomerization of the linolenic acids was observed at reaction temperatures as low as 250 C. Reactions carried out at higher temperatures and pressures, UP to the critical point of water, produced either/or degradation, pyrolysis, and polymerization, of the oils and resultant fatty acids. Introduction The development of enviromnentahy compatible manufacturing processes, which avoid the use of organic solvent, has become highly desired recently. A review of green manufacturing options has just been published (Anastas and Williamson, 1996), including an excellent review on the use of supercritical fluids by Tumas (Morgenstern et al., 1996). Such media avoid many of the objections and problems associated with organic solvents, including flammability, product contamination, and their associated disposal cost. To date, many processes have been conducted in the presence of supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-COz) due to its low cost, convenient critical properties, and relative inertness, particularly processing products intended for use in the food industry (King and List, 1996). Supercritical water (SC-HzO) and its subcritical analogue are also receiving increased interest as altematives to organic solvents (Shaw et al., 1991). The critical properties of SC-Hz0 are quite high (Z, = 374 C, PC= 218 atm, and pc = 0.32 g/mL) relative to those for SCCOs. Water has the capability of dissolving both nonpolar and polar solutes since its dielectric constant can be adjusted from a room temperature value of 80 to a value of 5 at its critical point. Therefore, water can solubilize most nonpolar organic compounds including most hydrocarbons and aromatics starting at 200-250 C and extending to the critical point (Gao, 1993; Connolly, 1966). This property of sub- and SC-H20 has been exploited since the early 1980s for the destruction of hazardous waste (Mode& 1989) and has been covered in several excellent reviews (Hutcheson and Foster, 1995; Savage et al., 1995). Recently, Hawthorne and co-workers (Yang et al., 1995; Hawthorne et al., 1994) have shown the potential of water as an extraction solvent in analytical chemistry, particularly when applied to the characterization of environmental containments in soil matrices. Several studies have been undertaken to explore the use of water in its nearcritical or critical state for conducting synthetic organic chemistry. Some of these include the oxidation of alkyl * Corresponding author. Telephone: (309) 681-6204. Fax: (309) 681-6686. Email: Hollidayrl@ncaurl.ncaur.gov. aromatics (Holliday, 1995), metal-catalyzed organic transformations (Parsons, 1996), the oxidation of methane (Lee and Foster, 1996; Savage et al., 1994) in hydrothermal systems (Katritzky et al., 1995), and the dehydration of alcohols (xu et al., 1991). Hydrolysis reactions have been an important option for many years in the processing of oils and fats for the oleochemical industry. These name reactions, such as the Twitchell process (Sonntag, 1979) or Colgate-Emery synthesis (Barnebey and Brown, 1948), of complex mixtures of fatty acids have historically been conducted at low pressures and elevated temperatures, although the Eisenlohr process (Eisenlohr, 1939) was facilitated at pressures approaching 240 atm. It is interesting to note that processes like the Colgate-Emery process are conducted at conditions similar to subcritical water (250 C and 50 atm), although historically they have not been interpreted in this light because the oil to water ratio is usually 2 to 1, making it more of a steam-based hydrolysis than a subcritical one. For this reason, we have conducted a more fundamental study of the hydrolysis of vegetable oils under sub- and supercritical water conditions where the density is more liquid&e (~0.5 ghnL) than gaslike. In this research, hydrolytic reaction conditions ranging in temperatures of 250-375 C have been applied to the hydrolysis of vegetable oils, such as soybean oil, linseed oil, and coconut oil. From the derived data, approximate conversion rates have been estimated and conditions optimized for the production of the derived fatty acids. Analytical characterization of reaction product mixtures has been accomplished by supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) (Chester, 1996) and gas chromatographic analysis of methyl esters of fatty acids (GC-FAME). The results of these baseline studies are expected to aid in the design of a continuous-flow conversion process employing sub- or supercritical water and to offer an alternative method that might be faster and devoid of catalyst residues for the processing of triglyceride-based fats and oils to their component fatty acid constituents. Materials and Methods Vegetable oils used in these experiments were as follows: coconut oil (EDKO 76), PVO Foods, Inc., St.

SO888-5885(96)00668-9 This article not subject to U.S. Copyright. Published 1997 by the American Chemical Society

Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., Vol. 36, No. 3, 1997 933

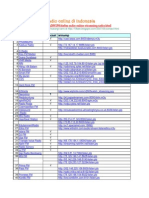

Table 1. Dependence of Conversion of Triglycerides (=-970/c) to Fatty Acids on Time and Temperaturea

Oil

reaction time (min) 20 15 20 69 15

reaction temperature (C) 270 280 280 260 270

\ 4

Thermocouple

soybean oil (FBD)b hydrogenated soybean oil linseed oil coconut oil

0 The density of water was 0.7 g/mL for data shown. b Retied, bleached, deodorized soybean oil.

Oven

Figure 1. Schematic of the reaction vessel in an oven, showing the placement of the thermocouple inside the vessel.

Louis, MS; hydrogenated soybean oil (17 Stearin), Van Den Bergh Foods Co., Lisle, IL; linseed oil, Minnesota Linseed Oil Co., Minneapolis, MN, soybean oil (refined, bleached, deodorized (RBD)), Archer Daniels Midland, Granite City, IL. Deionized water was used without further purification. The high-pressure batch reaction vessel (Figure 1) consisted of a 316 stainless steel &in.long coned and threaded nipple (1 inch o.d., g/is in. i.d.) capped at one end and fitted with a l/d in.- 1 in. 316 SS union at the other end (Autoclave Engineers, Erie, PA). The union was fitted with a l/s-i/d in. thermocouple adaptor in which a thermocouple (Type J, l/e in. o.d. Inconel sheath, Omega Engineers, Stamford, CT) was placed such that the tip of the thermocouple was approximately at the halfway point of the nipple. The vessel had an internal volume of 35.5 mL and a pressure rating of 10 000 psi. The thermocouple was connected to a digital readout and/or a chart recorder for an accurate reading of the temperature inside the vessel. The vessel was cooled by two opposing 12 in. air knives (Exair-Knife No. 2012, Exair Corp., Cincinnati, OH). Supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) analysis of the reaction products was performed on a Lee Scientific Series 600 SFC (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). The SFC unit was equipped with a timed injector (200 nL injection loop), which was held open for 0.5 s, and a Dionex SB-Phenyl-50 capillary column (10 m x 50 pm i.d., 0.25 pm film thickness). The flame ionization detector (FID) was operated at 350 C, and an integrator (Data Jet-CHz, Spectra-Physics, San Jose, CA) was used for data quantification. The column temperature was held at a constant of 100 C. The carrier gas was carbon dioxide (SFCYSFE grade, Air Products, Allentown, PA). The column pressure was held at 100 atm for 5 min and then increased to 240 atm at 4 atmlmin, followed by an increase to 320 atm at 10 atmlmin. GC-FAME (fatty acid methyl ester) analyses were performed according to previously described methods (House et al., 1994) on a HP5890 Series II GC using a FID detector (Hewlett Packard Co., Wilmington, DE) and a 100% polyibis(cyanopropyl)siloxa.ne] column (SP2340, Supelco, Inc., Bellefonte, PA, 60 m x 0.25 mm, 0.20 pm thickness). The GC oven parameters were modified slightly for better separation of the standards. The oven was held at 100 C for 5 min, then increased to 190 C at 3 C/min, then increased at 1 Wmin to 200 C and held for 15 min, and finally increased at 50 Clmin to 250 C and held for 1 min for a total time of 62 min. GC-MSD (mass selective detector) analysis of the FAMES was performed on a HP5890 Series II Plus GC interfaced with a HP597l.A MSD using the same column as described above.

In a typical reaction, 25 mL of water and 4 mL of vegetable oil were charged into the high-pressure reaction vessel. The reaction vessel was then placed upright into an oven preheated to approximately 350 C. The temperature of the reaction was monitored, and the oven was regulated to the desired temperature inside the vessel. The reaction was conducted at this temperature for a specified amount of time. The vessel was then removed from the oven and cooled with the air knives until it was cool to the touch (approximately lo13 min to reach 35 C). Workup of the reaction products usually consisted of pouring the vessel contents into a separatory funnel, adding a small amount of salt (NazSOd) to the water, and extracting the oil/water mixture with diethyl ether. The ether was then evaporated to leave an oil or a solid consisting of the hydrolyzed fatty acids and any unreacted triglycerides. This extract was then subjected to SFC to determine the degree of hydrolysis. GC-FAME analysis was then utilized to determine if the free fatty acid composition had been altered during the reaction.

Results and Discussion

Approximately 40 reactions were run during the course of this study utilizing the above-described procedures. To determine the parameters for a future continuous flow study, the time versus temperature ratio was studied to find a temperature which did not degrade the oils, in conjunction with a short residence time to optimize the reaction. For these reasons, the majority of the reactions were run for approximately 20 min and in the temperature range of 260-280 C. Table 1 tabulates the time and temperatures necessary for at least 97% conversion to free fatty acids based on the SFC analysis. Hydrolysis of these vegetable oils occurred between 15 and 20 min at 270-280 C and a density of 0.7 g/mL. The coconut oil hydrolyzed the quickest, whereas the linseed oil took the longest. Temperature plays a major role in the time of reaction, as can be seen by the hydrolysis of linseed oil. Lowering the reaction temperature by 20 C increased the reaction time from 20 to 69 min, with the density remaining consistent in the closed system. In many of the experiments, the collected water phase came out milky white, indicating au emulsion had formed containing free fatty acids. Hence, sodium sulfate was added to the water to salt-out the fatty acids. Past studies on the hydrolysis of organic esters and ethers, like dibenzyl ether, in water have shown that hydrolysis reactions occur more readily at densities of 0.45 g/mL or higher (Townsend et al., 1989). Consequently, the density for our initial experiments was set at 0.5 g/mL. This produces two phases, liquid end steam, at a density of 0.5 &nL and 280 C. To eliminate any~ambiguity as to which phase the hydrolysis was occurring in, the density was increased to 0.7 g/mL to ensure that there would be one phase at 270 C

934

Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., Vol. 36, No. 3, 1997

Table 2. Effect of Time and Temperature on the Distribution of Linolenic Acid Isomers and Degradation of Linseed Oil Shown as Percent of Total Fatty Acid0 time temperature

Acknowledgment We gratefully thank Scott Taylor, Dr. Fred Eller, and Dr. Mike Jackson for their assistance in the analysis of the oils and fats. Names are necessary to report factually on data; however, the USDA neither guarantees nor warrants the standard of the product, and the use of the name by the USDA implies no approval of the product to the exclusion that others may be suitable. Literature Cited

(min)

15 1.5 20 48 69

(C)

unreacted 270c 280 280 26ff 260

ctt, tctb

0 1.5 3.2 4.7 2.3 3.1

ttc

0.2 8.1 10.1 10.8 9.2 9.9

cct, ctc

0 1.9 2.8 3.3 2.2 2.5

tee

0 7.1 8.8 9.2 8.1 8.7

ccc

54.7 33.8 26.2 21.3 29.9 26.3

a The density of water was 0.7 g/mL. b c = cis and t = trans. c Not totally convertsd to free fatty acids.

(Rabenau, 1985). A density of 0.7 g/mL is su&ient to favor hydrolysis over pyrolysis and promotes solubilization of any polar intermediates during the hydrolysis. GC-FAME analysis was performed on all samples to determine if any degradation occurred to the fatty acids during hydrolysis. Saturated acids, such as caproic, caprylic, capric, lauric, myristic, palmitic, and stearic acids, were stable at temperatures below 300 C. The unsaturated fatty acids, oleic and linoleic acid, were also relatively unaffected at these same temperatures. However, linolenic acid levels were consistently reduced under these conditions, due to isomerization and degradation. For most reactions, approximately 90% of the linolenic acid was still present, but only 40-60% of the linolenic acid was in the original cis,cis,cis isomer form. The variation in this conversion proved to be dependent on time and temperature. Hydrolysis conducted at higher temperatures or longer reaction times produced less of the cis,cis,cis fatty acid (see Table 2). From Table 2, it can also be seen that the trans,trans,cis and trans,cis,cis isomers are present, and each represents lo-11% of the product composition after hydrolysis. This isomerization occurred even at 250 C, although not to as a great an extent as seen at 270-280 C. It is also interesting to note that the all-trans isomer is not formed in any significant amount. The isomer distribution patterns were found to be consistent during the course of these studies. Linoleic acid, with two double bonds, did not undergo any detectable amount of geometric isomerization. Several reactions were also performed at higher temperatures to see the effect on the oils. The RRD soybean oil was subjected to subcritical temperatures of 300 C for 11 and 25 min and 320 C for 13 min. The same oil was also processed at a supercritical temperature of 375 C for 8 min. These reactions yielded a very dark brown oil which was only partially soluble in ether and hexane. GC-FAME analysis indicated severe decomposition, pyrolysis, or polymerization, of the fatty acids, which was consistent with the color and nature of the resultant reaction mixture. Hydrogenated soybean oil exposed to the same conditions, also showed this onset of severe thermal degradation. Conclusion The use of subcritical water at high densities has proven to be an effective means of hydrolyzing vegetable oils to free fatty acids. Hydrolysis occurs rapidly, usually within 15-20 min, yielding 97% or better conversion. Supercritical water conditions tended to thermally degrade the reactants and products. Further research is being conducted to design and implement a continuous-flow reaction system based on these studies.

Anastas, P. T., Williamson, T. C., Eds. Green Chemistry; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1996. Bamebey, H. L.; Brown, A. C. Continuous Fat Splitting Plants Using the Colgate-Emery Process. J. Am. Oil Chem. Sot. 1949, 25,95-99. Chester, T. L. Supercritical Fluid Chromatography for the Analysis of Oleochemicals. In Supercritical Fluid Technology in Oil and Lipid Chemistry; King, J. W., List, G. R., Eds.; American Oil Chemists Society: Champaign, IL, 1996. Connolly, J. F. Solubility of Hydrocarbons in Water Near the Critical Solution Temperatures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1966,11, 13-16. Eisenlohr, G. W. U.S. Patent 2,154,835, 1939. Gao, J. Supercritical Hydration of Organic Compounds. J. Am. Ckm. Sot. 1993,115,6893-6895. Hawthorne, S. B.; Yang, Y.; Miller, D. J. Extraction of Organic Polhnants from Solids with Sub- and Supercritical Water. Anal. Ckm. 1994,66,2912-2920. Holhday, R. L. Organic Chemistry in Supercritical Water. Ph.D. Dissertation, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, 1995. House, S. D.; Larson, P. A.; Johnson, R. R.; DeVies, J. W.; Martin, D. L. Gas Chromatographic Determination of Total Fat Extracted from Food Samples Using Hydrolysis in the Presence of Antioxidant J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1994, 77, 960-965. Hutcheson, K. W., Foster, N. R., Eds. Innovations in Supercritical Fluids; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1995. Katritzky, A. R.; Shipkova, P. A.; Allin, S. M.; Barcock, R. A; Siskin, M.; Ohnstead, W. N. Aqueous High-Temperature Chemistry. 22. Nitrogen-Containing Heterocycles in Supercritical Water at 460 C. Energy Fuels 1995,9,580-589. King, J. W., List, G. R., Eds. Supercritical Fluid Technology in Oil and Lipid Chemistry; American Oil Chemists Society: Champaign, IL, 1996. Lee, J. H.; Foster, N. R. Direct Partial Oxidation of Methane to Methanol in Supercritical Water. J. Superwit. Fluids 1996,9, 99-105. Modell, M. Supercritical Water Oxidation. Chem. Phys. Processes Cornbust. 1989, El-E7. Morgenstem, D. A.; LsLacheur, R. M.; Morita, D. K.; Borkowsky, S. L.; Feng, S.; Brown, G. H.; Luan, L.; Gross, M. F.; Burk, M. J.; Tumas, W. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide as a Substitute Solvent for Chemical Synthesis and Catalysis. In Green Chemistry; Anastas, P. T., Williamson, T. C., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1996; pp 132-151. Parsons, E. J. Organic Reactions in Very Hot Water. CHEMTECH 1996,26,30-34. Rabenau, A. The Role of Hydrothermal Synthesis in Preparative Chemiatry.Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995,24,1026-1040. Savage, P. E.; Li, R.; Santini, J. T., Jr. Methane to Methanol in Supercritical Water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 1994, 7, 135-144. Savage, P. E.; Gopalan, S.; Mizan, T. I.; Martino, C. J.; Brock, E. E. Reactions at Suoercxitical Conditions: Applications and Fundamentals. Al&E J. 1995,41,1723-17781 Shaw, R. W.; Brill, T. B.; Clifford, A. A.; Eckert, C. A.; Franck, E. U. Supercritical Water a Medium for Chemistry. Chem. Eng. News 1991,69 (51), 26-43. Sonntag, N. 0. V. Fat Splitting. J. Am. Oil Chem. Sot. 1979,56, 729A-732A. Townsend, S. H.; Abrahan, M. A.; Huppert, G. L.; Klein, M. T.; Paspek, S. C. Hydrolysis in Supercritical Water: Identification

Id. and Implication of a Polar Transition State. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1989,28, 161-165. Xu, X.; De Almeida, C.; A&al, M. J., Jr. Mechanism and Kinetics of the Acid-Catalyzed Formation of Ethane and Diethyl Ether tiom Ethanol in Supercritical Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1991, 30, 1478-1485. Yang, Y.; Bewadt, S.; Hawthorne, S. B.; Miller, D. J. Subcritical Water Extraction of Polychlorinated Biphenyls from Soil and Sediment. Anal. Chem. 1995,67,4571-4576.

Eng. Chem. Res., Vol. 36, No. 3, 1997 Revised

935

Received for review October 17, 1996 manuscript received January 2, 1997 Accepted January 6, 1997@ IE960668F

* Abstract 15, 1997.

published

in Advance

ACS Abstracts,

February

You might also like

- Rice Cooker-En PDFDocument10 pagesRice Cooker-En PDFAbdulNo ratings yet

- Rice Cooker-En PDFDocument10 pagesRice Cooker-En PDFAbdulNo ratings yet

- Sodium Carbonate 1Document4 pagesSodium Carbonate 1Syahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Pipette Performance Check SOPDocument6 pagesPipette Performance Check SOPSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- HeatEffects of The TronaSystemDocument6 pagesHeatEffects of The TronaSystemSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Perlengkapan & Logistik Pribadi Perlengkapan:: Itenary Pangrango, 16 Juli 2019Document2 pagesPerlengkapan & Logistik Pribadi Perlengkapan:: Itenary Pangrango, 16 Juli 2019Syahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Flowsheet AroelDocument1 pageFlowsheet AroelSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Effective Supervisory ManagementDocument6 pagesEffective Supervisory ManagementSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- NPL Guide 69Document38 pagesNPL Guide 69BellbrujaNo ratings yet

- Pro Line Plus EngDocument20 pagesPro Line Plus EngAsterisk AwdaNo ratings yet

- Pipet Lite ManualDocument16 pagesPipet Lite ManualSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Table of Density of Pure WaterDocument2 pagesTable of Density of Pure WaterSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Spesifikasi Teknis Automatic Water Trement Plant Kapasitas 15 Mesin HDDocument2 pagesSpesifikasi Teknis Automatic Water Trement Plant Kapasitas 15 Mesin HDSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Thermo ChemistryDocument12 pagesThermo ChemistrySyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Dear Sir/madam, PT Well JakartaDocument1 pageDear Sir/madam, PT Well JakartaSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- OxyperDocument2 pagesOxyperSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Sodium PercarbonateDocument2 pagesSodium PercarbonateSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Official Magento User Guide (01!13!2010)Document219 pagesOfficial Magento User Guide (01!13!2010)Marvin Prejas FernandezNo ratings yet

- AnuDocument69 pagesAnuSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- PSS Sodium Percarbonate 164361Document6 pagesPSS Sodium Percarbonate 164361Syahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Daftar Radio Onlen 28062009Document4 pagesDaftar Radio Onlen 28062009Syahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Determining The Specific Heat Capacity of AirDocument22 pagesDetermining The Specific Heat Capacity of AirSyahrul Ramadhan0% (1)

- Installation GuideDocument4 pagesInstallation GuideSyahrul RamadhanNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- GeoMax Zipp02 DAT - enDocument2 pagesGeoMax Zipp02 DAT - enKoeswara SofyanNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 - Data & SignalDocument65 pagesCHAPTER 2 - Data & SignalIzzati RahimNo ratings yet

- Lesson 28Document4 pagesLesson 28MarcTnnNo ratings yet

- Adore Noir 028Document110 pagesAdore Noir 028Alex Scribd-Bernardin100% (3)

- Settlement Analysis of SoilsDocument22 pagesSettlement Analysis of SoilsMuhammad Hasham100% (1)

- R 2008 M.E. Power System SyllabusDocument24 pagesR 2008 M.E. Power System SyllabuskarthikeyanNo ratings yet

- Chemical Physics: Manish Chopra, Niharendu ChoudhuryDocument11 pagesChemical Physics: Manish Chopra, Niharendu ChoudhuryasdikaNo ratings yet

- Higher Mathematics 1 (H & B)Document3 pagesHigher Mathematics 1 (H & B)joseph.kabaso96No ratings yet

- Sensors: A New Approach For Improving Reliability of Personal Navigation Devices Under Harsh GNSS Signal ConditionsDocument21 pagesSensors: A New Approach For Improving Reliability of Personal Navigation Devices Under Harsh GNSS Signal ConditionsRuddy EspejoNo ratings yet

- Demand Controlled VentilationDocument58 pagesDemand Controlled VentilationthenshanNo ratings yet

- Lab 5 Extraction 3 Trimyristin From Nutmeg FS2010Document3 pagesLab 5 Extraction 3 Trimyristin From Nutmeg FS2010Sandip ThorveNo ratings yet

- Penerapan Metode Sonikasi Terhadap Adsorpsi FeIIIDocument6 pagesPenerapan Metode Sonikasi Terhadap Adsorpsi FeIIIappsNo ratings yet

- 2004-CHIN-YOU HSU-Wear Resistance and High-Temperature Compression Strength of FCC CuCoNiCrAl0.5Fe Alloy With Boron AdditionDocument5 pages2004-CHIN-YOU HSU-Wear Resistance and High-Temperature Compression Strength of FCC CuCoNiCrAl0.5Fe Alloy With Boron Additionsaurav kumarNo ratings yet

- Cows and ChickensDocument9 pagesCows and Chickensapi-298565250No ratings yet

- Industrial Training PresentationDocument16 pagesIndustrial Training PresentationChia Yi MengNo ratings yet

- BS EN 10228-12016 Non-Destructive Testing of Steel Forgings Part 1 Magnetic Particle InspectionDocument20 pagesBS EN 10228-12016 Non-Destructive Testing of Steel Forgings Part 1 Magnetic Particle InspectionudomNo ratings yet

- Meade Starfinder ManualDocument12 pagesMeade Starfinder ManualPalompon PalNo ratings yet

- Lighting and ShadingDocument44 pagesLighting and Shadingpalaniappan_pandianNo ratings yet

- A. Wipf - Path IntegralsDocument164 pagesA. Wipf - Path Integralsnom nomNo ratings yet

- Phy-153 Course OutlineDocument26 pagesPhy-153 Course OutlinealdricNo ratings yet

- Aperture 3Document355 pagesAperture 3Edu José MarínNo ratings yet

- WS - ICSE - VIII - Chem - Atomic StructureDocument4 pagesWS - ICSE - VIII - Chem - Atomic StructureShruthiNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word - Introduction V3Document220 pagesMicrosoft Word - Introduction V3glennNo ratings yet

- Rohit Kumar XII B PHYSICSDocument14 pagesRohit Kumar XII B PHYSICSRKNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE: Physics 0625/11Document16 pagesCambridge IGCSE: Physics 0625/11Jyotiprasad DuttaNo ratings yet

- Classical Theory of DetonationDocument20 pagesClassical Theory of Detonationalexander.lhoistNo ratings yet

- Jackson 11.14 Homework Problem SolutionDocument4 pagesJackson 11.14 Homework Problem SolutionPero PericNo ratings yet

- (0000-A) Signals and Systems Using MATLAB An Effective Application For Exploring and Teaching Media Signal ProcessingDocument5 pages(0000-A) Signals and Systems Using MATLAB An Effective Application For Exploring and Teaching Media Signal ProcessingAnonymous WkbmWCa8MNo ratings yet

- MCAT Chemistry ReviewDocument9 pagesMCAT Chemistry ReviewStellaNo ratings yet

- 3 Wave Transformation 3ppDocument19 pages3 Wave Transformation 3ppSigorga LangitNo ratings yet