Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Centre For Economic Performance: Occasional Paper No. 10 April 1996

Uploaded by

abcdef1985Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Centre For Economic Performance: Occasional Paper No. 10 April 1996

Uploaded by

abcdef1985Copyright:

Available Formats

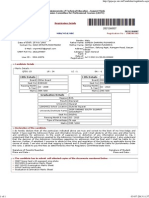

CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 10 April 1996 THE ROAD BACK TO FULL EMPLOYMENT R.

LAYARD

THE ROAD BACK TO FULL EMPLOYMENT Richard Layard

April 1996

Published by Centre for Economic Performance London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE R.Layard 1996 ISBN 0 7530 0299 X

THE ROAD BACK TO FULL EMPLOYMENT Richard Layard

Page 1. How Unemployed People are Treated 2. The Wage Bargaining Centre 3. Skill Formation and Relative Wages 4. Other Ideas Conclusions 4 16 18 19 23

Tables Figures References

25 27 32

The Centre for Economic Performance is financed by the Economic and Social Research Council.

THE ROAD BACK TO FULL EMPLOYMENT by Richard Layard

I am delighted to be giving this lecture in honour of Rudolf Meidner. I have always been a great admirer of the Swedish model and of its remarkable authors, Gosta Rehn and Rudolf Meidner, and I still believe it has an enormous amount to offer to the world. However, the model has come under enormous stress in the last five years and this is a good moment to assess whether it remains viable. something like full employment, and how? One must straight away distinguish between the short-run and longrun issues. Clearly Sweden is in a very difficult short-run situation Can Sweden return to

resulting from errors of macroeconomic policy. In the late 1980s there was an excessive expansion. This was followed in the early 1990s by an

excessive contraction, which greatly reduced the confidence both of consumers and firms. As a result the personal savings rate increased

dramatically and the investment rate of firms fell. This has produced a very low level of domestic demand. The power of fiscal policy to offset this is severely limited because any use of expansionary fiscal policy would produce an unacceptable budget deficit. This leaves monetary policy as the chief viable instrument of short-run economic policy, but if monetary policy is well judged it should be possible to secure not only (as is already under way) a strong export performance but also a

recovery of investment - which would ultimately lead to a recovery of consumption. In this way recovery will continue for some time. But the real question is, How far can recovery go before the labour market becomes so tight that inflationary pressures once more get out of hand? In other words, what level of employment in future will be

sustainable? That is the subject of this lecture. But before attempting an answer I should like to point out that by international standards the employment rate in Sweden is still above average. The simplest measure of employment performance is open unemployment. That is the proportion of people wanting to be economically active who are not currently able to be so. Even in 1994 the unemployment rate in Sweden was 8%, compared with the European average of 11% (see Table 1). A second measure of

employment performance is the proportion of the population of working age who are not in jobs. Once again Sweden has a much smaller

proportion of people not in jobs than the European average. The only criterion on which Sweden approaches the European average is one in which one adds together the numbers of unemployed and the numbers on schemes, as in the third line of the table. This is a peculiar concept. We are including with the unemployed some of the people who are undergoing training (because they reached it through unemployment) but not including the many thousands more who are training for some other reason. Similarly we are including with the unemployed some people who are in work because of the way in which that work is provided. This measure of labour market difficulty is not a particularly satisfactory one because it 2

includes so many disparate elements. By far the best measure of difficulty in the labour market is simply the level of open unemployment. If one is worried about unemployment it is because one is worried about the personal unhappiness caused by joblessness. In Sweden the evidence is that the unemployed are much less happy than those on schemes and in many countries which have been studied by my colleague Andrew Oswald it appears that unemployment is one of the major causes of human misery. 1 Indeed the difference in happiness between people when they are in work and out of work is far greater than the difference between when they are rich and when they are poor. This finding appears in both cross sectional studies and in longitudinal studies of the same people. So the central object of unemployment policy is to reduce open unemployment, and the main issue relating to schemes is whether or not they reduce open unemployment. A good deal more is understood about the causes of unemployment than is popularly believed. When our book on Unemployment 2 was

published, The Economist reported that few economists would disagree with the books central findings, and concluded that the book convincingly refutes the idea that countries have no choice but to live with high unemployment. In order to understand what causes the average level of unemployment over the cycle, it is best to compare the levels of unemployment across countries and then seek for institutional differences which might explain them. I want to talk about the three main differences which seem to be important and then to conclude with four or five others which are not. 3

The three important issues are (a) how unemployed people are treated, (b) how wages are determined and (c)what policies exist for skill formation.

1. How Unemployed People are Treated If one looks at the unemployment differences across countries one fact immediately strikes one (see Table 2). There is much less variation across countries in the proportions of the workforce who have been out of work for less than a year than there is in the proportions who have been out of work for over a year. While most countries have between 3 and 6% of people in short-term unemployment (under a year), the proportions of the workforce in long-term unemployment vary from virtually nil in the United States to over 10% in Spain. These figures are averages over the last fifteen years. So the first obvious step is to try and explain the huge variation in long-term unemployment. One possible explanation springs to mind at once - the length of time for which unemployment benefits are payable. This issue is explored in Figure 1 which shows that those

countries, like the United States and Japan, where unemployment benefit runs out in six months have a very small proportion of their unemployed in long-term unemployment. On the other hand, major European

countries, like Britain, Germany and France, where benefits are available for a very long time have up to half of their unemployment in the form of long-term unemployment. This should surprise nobody. If you pay people too long for inactivity then they will remain inactive for too long.

What is the policy conclusion?

One approach is simply not to

support peoples incomes at all after a while. That is the approach in the US. But, as we know, a policy of starving people back to work drives down the wages of low skilled people to very low levels, since this is the only way in which they can be employed. Thus unemployment is kept low but at the cost of creating an underclass of people either on low pay or outside the labour force engaged in criminal activity. Another response to the problem is to continue supporting peoples incomes but after a period only by paying them for some form of activity, either work or training. This has been the central idea of the Swedish active labour market policy and I believe that it is an idea of profound importance which Sweden has offered to the world. I sincerely hope that in these difficult times Sweden will not go back on this important commitment. For, I would like to stress, there are really only two alternatives to active labour market policy. The first is no form of income support and the generation of an underclass; the second is unconditional income support and massive long-term unemployment. Thus active labour market policy is based on a mixture of compassion and hard-headed realism. For the experience of countries like Britain has

shown clearly that it is impossible to operate the test of job availability unless you actually offer a person work. This is what Sweden has been able to do, at least until recently and it is an important reason why the Swedish unemployment rate remained so low in the 1980s when unemployment shot up in most of the rest of Europe. The reason why it is vital to prevent long-term unemployment is quite 5

simple.

Long-term unemployed people are unattractive to employers.

Therefore they are not treated as suitable recruits to fill vacancies. Thus you can quite well have very high long-term unemployment without any downward pressure on inflation. This is found repeatedly in equations which attempt to explain wages. For the same reason if many of the unemployed are long-term unemployed you will find a much higher level of total unemployment at any given level of vacancies, precisely because employers do not find long-term unemployed to be interesting people to fill these vacancies. Thus in the 1980s, as long-term unemployment rose in Western Europe, so the total level of unemployment at any given level of vacancies rose. The same did not happen in Sweden. This confirms that Sweden had a bulwark against mass unemployment in the face of the second oil shock which was lacking in Western Europe. That bulwark was the active labour market policy which prevented the growth of long-term unemployment and thus total unemployment at a given level of vacancies. The fact that the level of vacancies in Sweden is now so low indicates that there has so far been no collapse of the Swedish mechanisms in determining the equilibrium level of unemployment: Sweden is still in the depth of a major demand-led recession.

Criticism of active labour market policy There are three main criticisms which have been made of the view that active labour market policy has played a useful role in Sweden. The first is theoretical. Many people believe that you cannot increase total

employment by helping some people to get jobs, because all that can happen is that they take jobs from other people. In other words the total number of jobs is somehow fixed, independently of what is done to make people attractive to employers. There is clearly no basis for the assertion that the total number of jobs is fixed. Suppose, for example, we take an

extreme case. A territory is unpopulated and thousands of people move into it, will they all be unemployed because the number of jobs is fixed? Clearly not. Obviously the level of employment in that territory will

depend on how many people there are around available to be employed and attractive to employers. Exactly the same principle applies in a settled territory. The level of employment will respond to the number of people around who are attractive to employers. So suppose that Mr. A is currently unattractive to an employer because he has been out of work for so long and he receives training or other help that makes him attractive. A

particular employer decides to take him on, in preference to Mr. B who would have otherwise have been taken on. What happens to Mr. B?

Clearly the fact that he would have been taken on means that he is already attractive to employers. So now there is one extra person on the labour market who is attractive to employers; he will quite quickly find an employer who wants to take him on. Because Mr. A became employable as well as Mr. B, the total number of employable people in the economy has increased and thus there will be forces making for higher employment. However we need to distinguish between the medium run and the short run. In the medium run if there are more employable people in a territory there will be more employment. In the short run there is a range 7

of possibilities.

Suppose first that total nominal demand remains

unchanged. Then, when employers face an increased supply of labour, there will be a reduction in inflation, but employment will not at once adjust by the full increase in labour supply. If nothing more is done to alter nominal demand from what it would otherwise have been, eventually the price level will become sufficiently low (relative to what it would otherwise have been) for all the extra people to be employed. But that is a medium-run effect. However there is another possibility. Many countries now have an inflation target. This means that, if they see inflation falling below the target, their central bank will relax its monetary policy by, for example, reducing interest rates. In this case employment immediately expands in line with the increase in the number of employable people. This point is illustrated in Figure 2. The continuous line shows the initial trade-off between the level of employment and the change in inflation (measuring inflationary pressure). This augmented Philips Curve relation is shifted by active labour market policy so that at any level of unemployment there will tend to be lower inflationary pressure because there are more employable job seekers facing employers in the labour market. The

government can either now have the same employment and lower inflation, or the same inflation and higher employment, or a mixture of the two. If it decides on the same inflation as it had originally planned, employment will expand by the full amount of the increase in the number of employable people - even in the short run. Thus we should not worry unduly about the problem of substitution. 8

Of course, when Mr. A got his job he displaced Mr. B from the opportunity he would have otherwise had. But the fact that Mr. B was still looking for work then itself generated another job. For in order to control inflationary pressure the economy needs only a certain number of unemployed job seekers who are attractive to employers. If each unemployed person

becomes more attractive to an employer, then the total number of unemployed people required falls. It is helpful to reinforce this point by looking at the matter in terms of flows. As the long-term unemployed become more attractive to

employers, there is no reduction in the chances of re-employment for people who are already attractive i.e. the short-term unemployed. The only change is that the long-term unemployed find work more quickly. The flow of short-term unemployed who are hired per period remains as before, as does the flow of long-term unemployed. But the stock of long-term unemployed has fallen drastically because the chances of being hired have become so much better for long-term unemployed people. This means that even, though their flow of hires is constant, their stock has fallen. This is illustrated in Figure 3, which shows for Britain the flows through the labour market at steady state levels. Some 300,000 are

entering unemployment each month and the same number leave. 250,000 leave before they reach 12 months of unemployment and the other 50,000 leave later. If in Britain we had a more active labour market policy we would not have to increase that flow of hiring from long-term unemployment beyond 50,000 per month. But we would so increase the attractiveness of the long-term unemployed that we would need many 9

fewer of them in order for employers to be willing to select 50,000 per month. Thus the displacement and substitution issue is essentially a red herring. The key question is whether active labour market policy can make people more attractive to employers. This brings me to the second issue. Much of the research in Sweden, in particular, has cast doubt over the question of whether active labour market policy can make people more attractive to employers.3 The problem with most of these studies is that they are not able to control effectively for differences between those who are sent on programmes and those who are not. In many cases those who are sent on programmes will be people in special difficulty and therefore their performance would have been worse in the absence of the programme. Another problem with some studies is that they assume that people ought to be entering more regular employment while they are still on schemes. This does not seem altogether reasonable. It would be better to look at the total weeks of open unemployment which accrue to a collection of identical individuals entering unemployment

together, where one group is sent on a scheme and the other is not. These types of comparative studies between individuals are of very great importance but they cannot, of course, capture the system-wide effects of active labour market policy. For example, if you have a system where income is maintained after a year only by active measures, then this will affect the whole spirit with which unemployed individuals and the employment service staff approach their task in the first 12 months of a spell of unemployment. We can see this effect by looking at the exit rates 10

as a function of the duration of unemployment in Sweden compared with, for example, Britain (see Figures 4 and 5). In Sweden the exit rates are more or less constant, meaning that people continue to try to leave unemployment throughout the first 12 months because they know that after then life on benefits will come to an end. In Britain people adjust to life on benefits and allow themselves to become less attractive to employers as their duration of unemployment continues. We can also see that once benefits end people in Sweden become very much more likely to find work. These effects are not ones which can be studied by comparing those exposed to schemes and those not exposed to schemes. They are effects of the system which affect everybody. The thing which we can be most sure of in Sweden is that the puritanical aspects of the system help to sustain the re-entry rates into employment. If we take that as the first point and then add the second, that we would not tolerate a system which was purely negative, we end with a very strong case for active labour market policy, even where we have some difficulty in identifying effects on individuals. However, there are of course ways of trying to look at the systemwide effects of the policy through aggregate Phillips Curve relationship. This is the approach which has been taken by Lars Calmfors.4 He has examined separately the effect on wage pressure of the number of people in open unemployment and the number of people on schemes. If schemes reduce open unemployment, then the number of people on schemes should reduce wage pressure, thus making it possible to have the same wage pressure with lower open unemployment. 11 Using time series analysis,

Calmfors does not generally find a negative effect of the number of people on schemes, although some more microeconomic studies suggests favourable effects of training programmes.5 The trouble with these studies is that they are relying on time series movements in the numbers on programmes to identify the effect of a continuing labour market policy. Clearly the numbers on the programmes are highly endogenous even when the policy does not change and this is difficult to allow for even by the most imaginative econometric methods. Probably the best evidence that we can get on the effect of active labour market policy in general is through cross sectional international comparisons and I would give the greatest weight to that. 6 It appears to be fashionable in Sweden now to say that labour market policy did not account for Swedens low unemployment in the 80s and earlier (and that the wage bargaining system had no effect either). Instead from both left and right we hear explanations in terms of the high level of demand brought about by repeated devaluations. This kind of explanation is particularly surprising from liberal economists who normally deny the long-run effects of nominal policies. It is in any case a total irrelevance because the mystery is why unemployment remained so low without an inflationary explosion. The main need is not to explain the level of

unemployment but the relationship between unemployment and inflationary pressure. Through demand side explanations it is truly impossible to

explain why through the 80s Sweden bucked the European unemployment trend without a terrible inflation explosion.

12

What to do? If active labour market policy is an important building block in the road to full employment, what should be the main components of an effective labour market policy? The first issue is what kind of activity should be provided. Surely some retraining is useful, especially for people who had good skills in industries which became obsolete. But, for people who had always low skill levels, it is not so clear that skills can be effectively raised in middle age, and it is clearly absurd to allow people to take one course after another and return straight back to unemployment. In my view the most important activity is to find ways of getting people back into employment with regular employers doing regular work. Only in this way will workers have a chance to build-up a convincing work record on the basis of which they can either be kept on by the existing employer or hired by another. Thus I would give a central role to

recruitment subsidies for people who have proved difficult to place. For the reasons already given, there need be no major effort to ensure that the work which is done is work which would not otherwise have been done. Indeed such a requirement would be utterly self defeating. Clearly employers cannot be allowed to hire people on the subsidy while at the same time they are laying off other people. But that should be the

minimum requirement. Both private and public sector employers should be eligible to employ long-term unemployed people on the basis of a subsidy in regular jobs. If not enough places can be found (even after armtwisting) then of course some special schemes will have to be mounted.

13

But relief works of this kind should be regarded as a second tier system of support. To find the necessary places requires a strong employment service. Any thought of cutting the staff on the employment service would be a false economy. Indeed it is tragic that, simply because the numbers of unemployed have grown, the frequency which they receive counselling and monitoring has been reduced. As regards the level of benefits, it seems inevitable that after some period (or some number of spells of unemployment) these should be reduced below their present level. It is less important whether they are then provided through a social welfare system or through an unemployment insurance system, than that they are kept within the existing framework of relationship with the employment service. Clearly no one should be

allowed to continue on social welfare for more than 12 months without being provided with at least six months of activity. Equally after some period unemployed people will have to be required to accept jobs of a kind which they are currently allowed to reject.

2. The Wage Bargaining System The second factor which has a profound effect on the average level of unemployment in a country is the way in which wages are determined. While union activity in wage bargaining may create some extra wage pressure other things equal, it is obviously the case that, when you have very high union membership and the unions bargaining at a centralised

14

level, this creates a completely different situation and can lead to a reduction in wage pressure as compared with decentralised union bargaining. This is essentially the explanation of the famous hoop-shaped relationship reported by Calmfors and Driffill7: countries with centralised bargaining have low unemployment and countries with less centralised bargaining have higher unemployment, until you reach countries which are completely decentralised which have lower unemployment. However,

Calmfors and Driffill draw completely the wrong conclusion from the policy point of view because the countries which they identify as having decentralised bargaining (above all the United States) in fact have no bargaining at all because they have no unions. Thus the idea that if you cannot maintain a centralised bargaining system in its fully effective form you should move to a completely decentralised system with fully active unions is a fallacy. For a given level of unionisation the more

decentralised the system the more wage pressure there will be. It is easy to see why decentralisation produces wage pressure. Each group tries to improve its position by raising its wages relative to every other group and thus relative to the prices of the products produced by other groups. This leads to leap-frogging behaviour, which generates an inflationary impulse which can only be offset by sufficiently high unemployment. Even where there are no unions, there are still some

tendency for this to happen amongst employers - thus the so-called efficiency wage theory of unemployment. Thus there is no case in Sweden for the view that more decentralised wage bargaining would be favourable to employment. Our research shows 15

that coordination of wage setting is important in reducing unemployment both coordination on the union side and on the employer side. It would be very much better if the SAF could persuade its members to go down this route. But, even if the employers are unwilling to coordinate, it is important that the union side do so in the interests of their members who would otherwise become unemployed. The LO is to be greatly praised for its efforts in this direction. However, the LO has not been fully successful in this direction in 1995 and the likely level of wage inflation in Sweden over the next three years is decidedly worrying, considering the high level of unemployment from which it is occurring.

3. Skill Formation and Relative Wages I turn now to the third element in the Swedish model, the solidaristic wage policy. Clearly a centralised system of wage determination works best when there is no need for changes in relative wages. But it is very difficult to maintain such a situation when there are huge changes in the relative demand for labour. In particular there is the huge problem of the steady collapse in the demand for low skilled labour. This is perhaps the greatest single problem confronting modern industrial societies. In the face of it there are only two possibilities. The first is to reduce the supply of unskilled labour at least as fast as the demand for it collapses. Some countries appear to be successfully achieving this, such as Germany, where relative wages have altered very little and there has been no increase in the unemployment rate of low

16

skilled as compared with high skilled people. The other possibility is to allow the continued existence of a group of unskilled people but to ensure their continued employment through a fall in their relative wage. This is the route which has been followed in the USA, where the rate of increase in the supply of high relative to low skilled people has been slower than in Western Europe. Only a huge increase in the US wage dispersion has made it possible to prevent a huge rise in the unskilled unemployment rate compared with the skilled unemployment rate - though this has also in fact risen. Turning to the Swedish situation, there are clearly two routes to go. The first is to ensure that the minimum level of skill in the work force rises rapidly. The second concerns the wage structure. If full employment is the over-arching objective, then as a last resort an element of relative wage flexibility will be necessary. It may not need to be used, but the possibility of using it must be there. This is to my mind the one element in the Swedish model where some degree of compromise may be needed. But in my view the old recipe of centralised bargaining and active labour market policy remain Swedens best hope for achieving and maintaining a high level of employment.

4. Other Ideas However, quite other ideas are also in the air, many of them advocated in the OECD Jobs Study or in the Delors White Paper.8

17

Lower employment taxes Perhaps the most common of these is the proposal to lower the employment tax, the infamous tax on jobs, replacing it by a tax on environmentally unfriendly products. Though this might be good from an environmental point of view, there is little convincing evidence that it would affect the level of unemployment, for two reasons. First, there is no evidence that taxes have any long-run effect on unemployment. If they did, unemployment would surely be very much higher now than it was in the nineteenth century. However, there will be a short-term impact due to real wage resistance.9 When workers find that the real value of their take-home pay goes down, they fight back, thus generating inflationary pressure. Thus any extra tax wedge between the value of the marginal product and take-home pay has a short run impact on inflationary pressure. But - and this is the second point - there is no clear evidence that different elements in the wedge have different effects, be they employment taxes, income taxes or product taxes. Thus no one should kid themselves that they have a policy that will make any major impact when they talk about shifts from taxes on employment or taxes on products. But clearly a

reform of the employment tax which had a structural dimension, like cutting taxes on low skilled wages and raising them on skilled wages would have a more significant effect.

18

Employment protection Another popular proposal is to reduce the degree of employment protection (i.e. redundancy pay and job security provisions). Clearly these have some deterrent effect on hiring rates, but they also have a deterrent effect on firing rates. After 10 years of research no one can say which way the net effect of these goes. Probably the worst effect of employment protection is in increasing insider power, but even then it may not be a crucial issue affecting the overall level of employment.

Work sharing and early retirement A third proposal is that jobs could be created by introducing some upper limit on the number of hours per week or some other general incentive towards work-sharing. Clearly in a recessionary context there is a great deal to be said for reducing hours per work, so that the firm retains contact with its workforce ready for the upturn. This is in the interests of the firm and its workers and can probably be arranged without state involvement. But there is no reason to think that on average over the cycle a regime in which there was shorter hours would generate more jobs. Of course, it would initially, but that would only generate more inflationary pressure and the economy would then be deflated to eliminate the inflation until the original level of unemployment was restored. The same is true of early retirement. Efforts to reduce the number of people in the work force will not reduce the unemployment rate. Instead

19

they will generate upward pressure on wages which will only be offset by a reduction in employment.

Profit sharing Many people have been attracted by Martin Weitzmans idea that an economy with profit-sharing tends to have lower unemployment. 10 But

Weitzmans results actually relate to the extent of fluctuations rather than the average level of unemployment over the cycle. The problem of leapfrogging would not be eliminated by profit-sharing, and there is no convincing evidence that the average level of unemployment would be lower in an economy with profit-sharing. Though Japan has profit-sharing in the formal sector of the economy, its low average unemployment over the cycle appears to be largely due to the extreme wage flexibility in the informal sector.

Productivity growth Finally there is the question of whether higher productivity growth would be good for unemployment. Clearly higher productivity in itself can have no effect on unemployment, otherwise unemployment would have disappeared long ago. But productivity growth rates which differ widely across the sectors, causing the need for redeployment of labour, are likely to raise the unemployment rate. On the other hand a widespread increase in the rate of productivity growth would probably reduce unemployment, because when real incomes are rising faster than people expected it is much

20

easier to contain inflationary pressure than otherwise. This is at least a partial explanation of the high employment rates of the 1950s and 60s throughout Europe, and it is certainly possible that the high tech revolution will have the same beneficial effects at the beginning of the next century. However it is not something that we should count on.

Conclusions So my conclusions are that the right course for Sweden is to stick to the active labour market policy and to continue the fight to achieve consensus over collective wage-bargaining in the interests of the whole society. Some people say that active labour market policy can simply not be sustained when there is very high unemployment. I would reply that, if it is not, then you will never get back to low unemployment. For there is a strong cultural element in the way in which labour market institutions operate. If the unemployed understand that they will have to become

active, this will colour their perception of the range of possibilities open to them. Once you change the regime because you temporarily cannot

sustain it, the assumptions on which it is based will be eroded. It will be very difficult to reestablish the regime again. We have seen how in

Western Europe the benefit system provided no adequate bulwark against the upward shock to long-term unemployment arising from the second oil shock.

21

In the 1980s the Swedish system held up.

But it has not been

completely successful in withstanding the huge shock of the 1990s Swedish deflation. However it is important not to give up. Even now open unemployment in Sweden is not high by European standards, and unemployment will be coming down more in Sweden than in the rest of Europe. If employment offices are allowed to give up on the activity principle now because there are no jobs, this will influence the whole of the system in future, exactly as happened in the rest of Europe in the early

*80s. But if Sweden adheres to the Swedish model, it will revert to being

a low unemployment country by European standards - that is unless, as I earnestly hope, the Swedish model is also adopted in the rest of Europe.

22

TABLE 1 Non-employment Rates (%) 1991 Sweden UNEMPLOYMENT as % of Labour Force NON-EMPLOYMENT as % of Pop 15-64 UNEMPLOYED + SCHEMES as % of Labour Force 3 22 7 EU 9 39 10 1994 Sweden 8 30 13 EU 11 42 13

23

TABLE 2 Percentage of the Workforce Unemployed 1981-1995 Total Unemployment US Japan Europe (12) Belgium Denmark West Germany Greece Spain France Ireland Italy Netherlands Portugal UK Sweden Austria Australia 6.9 2.5 9.7 10.1 8.3 5.8 7.9 19.0 9.6 16.3 10.1 9.6 6.3 9.6 3.8 3.5 8.4 Unemployed Under 1 Year 6.3 2.1 4.7 2.8 5.8 3.2 4.4 8.0 5.4 7.0 3.6 4.9 4.1 5.4 3.5 3.1 6.2 Unemployed Over 1 Year 0.6 0.4 5.0 7.3 2.5 2.6 3.5 11.0 4.2 9.3 6.5 4.7 2.2 4.2 0.3 0.4 2.2

New Zealand 6.3 5.7 0.6 Sources: Total unemployment rate - US, Japan, Europe (12), Belgium, Denmark, West 1. Germany, Greece, Spain, France, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal and UK: European Economy, No.59, 1995. Sweden, Austria, Australia and New Zealand: OECD, Economic Outlook, No.56, December 1994. Long-term and short-term unemployment rates calculated using proportions 2. from Table 1, Preventing Long-Term Unemployment in Europe, R. Layard, Centre for Economic Performance, Working Paper No. 565, 1995.

24

REFERENCES 1. Clark, A. and Oswald, A., Unhappiness and Unemployment, Economic Journal, Vol.103, May 1994. Layard, R., Nickell, S. and Jackman, R., (1991) Unemployment, Macroeconomic Performance and the Labour Market, Oxford University Press. Bjrklund, A., Evaluations of Swedish Labour Market Policy, Swedish Institute for Social Research, University of Stockholm, Finnish Economic Papers, Vol.3(1), 1990. Calmfors, L. and Skedinger, P., Does Active Labour Market Policy Increase Employment?, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Spring, 1995, pp.91-109. Edin, P-A., et al., (1994) Wage Behaviour and Labour Market Programmes in Sweden: Evidence from Micro Data, in Tachibanaki, T. (ed.), Labour Market and Macroeconomic Performance: Europe, Japan and the US, Macmillan Press. Layard, R., et al., (1994) The Unemployment Crisis, Oxford University Press. Calmfors, L. and Driffill, J., Centralisation of Wage Bargaining and Macroeconomic Performance, Economic Policy, Vol.6, April 1988. Commission of the European Communities, Growth, Competitiveness, Employment, The Challenges and Ways Forward into the 21st Century, White Paper, Brussels, 1993. OECD, The OECD Jobs Study, Unemployment in the OECD Area, 1950-1995, Paris, 1994.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

25

9. 10.

Hicks, J., (1974) The Crisis in Keynesian Economics, Blackwell. Weitzman, M., (1984) The Share Economy , Harvard University Press.

26

You might also like

- Dollar at The Crossroads: Long-Term Interest RatesDocument54 pagesDollar at The Crossroads: Long-Term Interest Ratesist0100% (2)

- Ruane, Cunniff & Goldfarb Investor Day 2009 - TranscriptDocument24 pagesRuane, Cunniff & Goldfarb Investor Day 2009 - TranscriptThe Manual of IdeasNo ratings yet

- AAU Prospective Graduate 2023Document293 pagesAAU Prospective Graduate 2023semabay100% (2)

- Research Methods For ManagementDocument176 pagesResearch Methods For Managementrajanityagi23No ratings yet

- The Swiss Confederation - A Brief Guide 2016Document84 pagesThe Swiss Confederation - A Brief Guide 2016Swiss Consulate New York100% (1)

- Meidner (1992) - Rise and Fall of The Swedish ModelDocument13 pagesMeidner (1992) - Rise and Fall of The Swedish ModelmarceloscarvalhoNo ratings yet

- HSC Economics Practice QuestionsDocument4 pagesHSC Economics Practice QuestionsAnkita Saini100% (2)

- British Culture: The Economy and Everyday Life WORDDocument35 pagesBritish Culture: The Economy and Everyday Life WORDThảo Phan100% (4)

- Preventing Absenteeism at Work: Understand and beat this widespread phenomenonFrom EverandPreventing Absenteeism at Work: Understand and beat this widespread phenomenonNo ratings yet

- How Countries CompeteDocument137 pagesHow Countries CompeteJim Freud100% (3)

- ILO - Social Justice & Growth - The Role of The Minimum Wage (2012)Document128 pagesILO - Social Justice & Growth - The Role of The Minimum Wage (2012)supertech86No ratings yet

- Why Are European Countries Diverging in Their Unemployment Experience?Document38 pagesWhy Are European Countries Diverging in Their Unemployment Experience?danielpupiNo ratings yet

- Chapter - I IntorductionDocument36 pagesChapter - I IntorductionMohd Natiq KhanNo ratings yet

- Effect of Early Retirement Schemes On Youth EmploymentDocument10 pagesEffect of Early Retirement Schemes On Youth EmploymentMarco ParigiNo ratings yet

- InternatiInternational Lessons ReportDocument51 pagesInternatiInternational Lessons ReportTinaStiffNo ratings yet

- Thesis in Social Studies PDFDocument7 pagesThesis in Social Studies PDFdnnvbpvh100% (2)

- Term Paper GDP Analysis of SwitzerlandDocument10 pagesTerm Paper GDP Analysis of SwitzerlandAli RazaNo ratings yet

- Austerity Measures Across Europe: Introduction: The Austerity SpectrumDocument4 pagesAusterity Measures Across Europe: Introduction: The Austerity SpectrumelizzalexNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Bottom Line: The Challenges and Opportunities of A Living WageDocument77 pagesBeyond The Bottom Line: The Challenges and Opportunities of A Living WageJoaquín Vicente Ramos RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Low Inflation Targeting Raises Long-Term UnemploymentDocument23 pagesLow Inflation Targeting Raises Long-Term UnemploymentAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- Temporary Employment Agencies: A Route For Immigrants To Enter The Labour Market?Document44 pagesTemporary Employment Agencies: A Route For Immigrants To Enter The Labour Market?justoneoftheguysNo ratings yet

- The Mystery of Spain's Perpetual Jobs Problem: Euro EconomicsDocument8 pagesThe Mystery of Spain's Perpetual Jobs Problem: Euro EconomicsAlejandroNo ratings yet

- Unemployment DissertationDocument5 pagesUnemployment Dissertationticwsohoress1974100% (1)

- Entrepreneurship and The Youth Labour Market Problem: A Report For The OECDDocument29 pagesEntrepreneurship and The Youth Labour Market Problem: A Report For The OECDfadligmailNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Unemployment RateDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Unemployment Rateafnhinzugpbcgw100% (1)

- Whose Welfare State Now?Document12 pagesWhose Welfare State Now?OxfamNo ratings yet

- WP 427Document19 pagesWP 427rakib54bdNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics For Today 8th Edition Tucker Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument28 pagesMacroeconomics For Today 8th Edition Tucker Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFKarenChapmankzabj100% (10)

- Unemployment and Inflation DissertationDocument4 pagesUnemployment and Inflation DissertationPayToDoPaperUK100% (1)

- Macroeconomics For Today 8th Edition Tucker Solutions ManualDocument7 pagesMacroeconomics For Today 8th Edition Tucker Solutions Manualjerryholdengewmqtspaj100% (31)

- Minimum Wage Research Paper ThesisDocument4 pagesMinimum Wage Research Paper Thesisaypewibkf100% (1)

- Chapter 26 - Business Cycles, Unemployment and Inflation ExplainedDocument20 pagesChapter 26 - Business Cycles, Unemployment and Inflation ExplainedPavan PatelNo ratings yet

- A Bubble in ComplacencyDocument10 pagesA Bubble in Complacencyrichardck61No ratings yet

- Atkinson Pobreza y Exclusión SocialDocument122 pagesAtkinson Pobreza y Exclusión SocialMaga69No ratings yet

- Term Paper About Unemployment RateDocument4 pagesTerm Paper About Unemployment Rateafdtsdece100% (1)

- More Than A Minimum: The Final ReportDocument54 pagesMore Than A Minimum: The Final ReportResolutionFoundationNo ratings yet

- Inflation AND Unemployment: Presented byDocument27 pagesInflation AND Unemployment: Presented bySiddhartha MishraNo ratings yet

- PretDocument5 pagesPretkazuyaliemNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Minimum WageDocument4 pagesDissertation On Minimum WageWillYouWriteMyPaperForMeAlbuquerque100% (1)

- Thesis On Okuns LawDocument8 pagesThesis On Okuns Lawshannongutierrezcorpuschristi100% (2)

- A Research Paper On UnemploymentDocument6 pagesA Research Paper On Unemploymentipdeptulg100% (1)

- Research PaperDocument18 pagesResearch PaperphirlayayadilNo ratings yet

- HDRP 2010 30Document71 pagesHDRP 2010 30Pheng CheaNo ratings yet

- Active Aging in Economy and Society: Carl Bertelsmann Prize 2006From EverandActive Aging in Economy and Society: Carl Bertelsmann Prize 2006No ratings yet

- Youth Unemployment in Europe and The World: Causes, Consequences and SolutionsDocument13 pagesYouth Unemployment in Europe and The World: Causes, Consequences and SolutionsAbdoul RahimNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Economic Development PDFDocument7 pagesThesis On Economic Development PDFlniaxfikd100% (2)

- Enequality in WorldDocument181 pagesEnequality in World0bhimsingh100% (1)

- Mjor Issues of Macro EconomicsDocument5 pagesMjor Issues of Macro EconomicsnisarNo ratings yet

- Unemployment Dissertation ProposalDocument8 pagesUnemployment Dissertation ProposalProfessionalPaperWriterPortland100% (1)

- RL352d 5 March 2003Document22 pagesRL352d 5 March 2003hajpantNo ratings yet

- Principle 8: A Country'S Standard of Living Depends On Its Ability To Produce Goods and ServicesDocument6 pagesPrinciple 8: A Country'S Standard of Living Depends On Its Ability To Produce Goods and ServicesJanine AbucayNo ratings yet

- Local Media6430527557717518478Document8 pagesLocal Media6430527557717518478Bianca SyNo ratings yet

- Okuns Law Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesOkuns Law Literature Reviewaflskkcez100% (1)

- Tugas Problem Set 4 Ekonomi ManajerialDocument4 pagesTugas Problem Set 4 Ekonomi ManajerialRuth Adriana100% (1)

- Unemployment Thesis TopicsDocument4 pagesUnemployment Thesis Topicsivanirosadobridgeport100% (2)

- Commentary: The Search For Growth: N. Gregory MankiwDocument6 pagesCommentary: The Search For Growth: N. Gregory MankiwtegarpradanaNo ratings yet

- Economist Insights 20120528Document2 pagesEconomist Insights 20120528buyanalystlondonNo ratings yet

- European EconomyDocument10 pagesEuropean EconomyDani FajarNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Economic IndicatorsDocument6 pagesUnit 2 Economic IndicatorsAdjepoleNo ratings yet

- Accenture - Seven Myths of AgingDocument8 pagesAccenture - Seven Myths of AgingDeepak SharmaNo ratings yet

- Thesis UnemploymentDocument7 pagesThesis UnemploymentPaperWritingServicesBestUK100% (2)

- Term ReportDocument5 pagesTerm ReportHaider AbbasNo ratings yet

- Examination of Witness (Questions 100-117) : Parliamentary BusinessDocument4 pagesExamination of Witness (Questions 100-117) : Parliamentary BusinessJohn Adam St Gang: Crown ControlNo ratings yet

- ECO2x 2018 231 Statistics Labour Market R0-EnDocument2 pagesECO2x 2018 231 Statistics Labour Market R0-EnElsa PucciniNo ratings yet

- The Blind Decades: Employment and Growth in France, 1974-2014From EverandThe Blind Decades: Employment and Growth in France, 1974-2014Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Sales and Distribution MGTDocument89 pagesSales and Distribution MGTNitin MahindrooNo ratings yet

- Atul LTD 1Document8 pagesAtul LTD 1abcdef1985No ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis Training Certificate for Jaimish ChampaneriDocument1 pageFundamental Analysis Training Certificate for Jaimish Champaneriabcdef1985No ratings yet

- SSRN Id2179030Document47 pagesSSRN Id2179030abcdef1985No ratings yet

- GtuDocument3 pagesGtujigyesh29No ratings yet

- Advertisement LetterDocument1 pageAdvertisement Letterscribe03No ratings yet

- Paper-Iii Commerce: Signature and Name of InvigilatorDocument32 pagesPaper-Iii Commerce: Signature and Name of Invigilator9915098249No ratings yet

- Gujarat Technological University: Practical Examinations of MBA ProgrammeDocument1 pageGujarat Technological University: Practical Examinations of MBA Programmeabcdef1985No ratings yet

- Paper IDocument19 pagesPaper IPallavi PahujaNo ratings yet

- 33Document32 pages33paritosh7_886026No ratings yet

- Finance, Comparative Advantage, and Resource Allocation: Policy Research Working Paper 6111Document37 pagesFinance, Comparative Advantage, and Resource Allocation: Policy Research Working Paper 6111abcdef1985No ratings yet

- Correcting Real Exchange Rate Misalignment: Policy Research Working Paper 6045Document48 pagesCorrecting Real Exchange Rate Misalignment: Policy Research Working Paper 6045abcdef1985No ratings yet

- Gujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails NishantDocument1 pageGujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails Nishantabcdef1985No ratings yet

- Gujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails NishantDocument1 pageGujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails Nishantabcdef1985No ratings yet

- Gujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails VinayDocument1 pageGujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails Vinayabcdef1985No ratings yet

- Supplymentary NotesDocument68 pagesSupplymentary Notessharktale2828100% (1)

- OP002Document44 pagesOP002abcdef1985No ratings yet

- Effect of Product Patents On The Indian Pharmaceutical IndustryDocument105 pagesEffect of Product Patents On The Indian Pharmaceutical Industryabcdef1985No ratings yet

- NLDocument8 pagesNLabcdef1985No ratings yet

- PEFA2010Document134 pagesPEFA2010abcdef1985No ratings yet

- Effect of Product Patents On The Indian Pharmaceutical IndustryDocument105 pagesEffect of Product Patents On The Indian Pharmaceutical Industryabcdef1985No ratings yet

- On Dividend Restrictions and The Collapse of The Interbank MarketDocument22 pagesOn Dividend Restrictions and The Collapse of The Interbank Marketabcdef1985No ratings yet

- Bstract: Setting The Stage For Reforms, Provides A Framework That Spells Out Key Areas of ReformDocument1 pageBstract: Setting The Stage For Reforms, Provides A Framework That Spells Out Key Areas of Reformabcdef1985No ratings yet

- OP001Document19 pagesOP001abcdef1985No ratings yet

- OP005Document19 pagesOP005abcdef1985No ratings yet

- CEP Discussion Paper No 1121 February 2012 Why Has China Grown So Fast? The Role of International Technology Transfer John Van Reenen and Linda YuehDocument27 pagesCEP Discussion Paper No 1121 February 2012 Why Has China Grown So Fast? The Role of International Technology Transfer John Van Reenen and Linda Yuehabcdef1985No ratings yet

- OP006Document28 pagesOP006abcdef1985No ratings yet

- OP009Document31 pagesOP009abcdef1985No ratings yet

- OP008Document16 pagesOP008abcdef1985No ratings yet

- Food Price Inflation IndiaDocument2 pagesFood Price Inflation IndiaZaman AliNo ratings yet

- Economics ALevel 2018 Mark Scheme by The One and OnlyDocument31 pagesEconomics ALevel 2018 Mark Scheme by The One and OnlyRashmeeta ThadhaniNo ratings yet

- Over Population in PakistanDocument3 pagesOver Population in PakistanTubi NazNo ratings yet

- Business Cycles and Unemployment TutorialDocument5 pagesBusiness Cycles and Unemployment TutorialBernard Walker50% (2)

- Unit 2 - Fundamental Analysis AKTUDocument50 pagesUnit 2 - Fundamental Analysis AKTUharishNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For International Financial Management 13th EditionDocument36 pagesTest Bank For International Financial Management 13th Editionancientypyemia1pxotk100% (47)

- Problem Set 6 EC 1210 Fall 2013 Rahman Due Date SolutionsDocument3 pagesProblem Set 6 EC 1210 Fall 2013 Rahman Due Date SolutionsisaacmlNo ratings yet

- Principles of Economics Chapter 20Document26 pagesPrinciples of Economics Chapter 20rishisriram04No ratings yet

- Revenue Growth Management The Time Is NowDocument6 pagesRevenue Growth Management The Time Is NowAbdel AzizNo ratings yet

- BBS 1st Semsyllabus 1658312821 GsmsDocument24 pagesBBS 1st Semsyllabus 1658312821 Gsmsambikeshwor joshiNo ratings yet

- IBF NotesDocument35 pagesIBF NotesAsad Shah100% (1)

- A Project Work Report Proposal: A Study Analysis On The Interested of Nepal Bank LimitedDocument7 pagesA Project Work Report Proposal: A Study Analysis On The Interested of Nepal Bank LimitedKanaj NamNo ratings yet

- Economics Assingment - 1st Sem - Radhika KhaitanDocument20 pagesEconomics Assingment - 1st Sem - Radhika KhaitanSandeep TomarNo ratings yet

- MACRO Assignment 2Document5 pagesMACRO Assignment 2marta lis tuaNo ratings yet

- City VisionsDocument266 pagesCity VisionsRamona Lupean0% (1)

- Accounting for Inventory Valuation Methods Research ProposalDocument66 pagesAccounting for Inventory Valuation Methods Research ProposalAyman Ahmed Cheema100% (1)

- Britannia Annual Report Performance and Operations HighlightsDocument17 pagesBritannia Annual Report Performance and Operations HighlightsajthebestNo ratings yet

- JAMB Economics Syllabus by LarnEduDocument19 pagesJAMB Economics Syllabus by LarnEduaraimoabdullahNo ratings yet

- Central Bank and Monetary Policy ExplainedDocument70 pagesCentral Bank and Monetary Policy ExplainedKoon Sing ChanNo ratings yet

- Tilenga ESIA Volume VI (A) - 28/02/19 - p509 To 819Document311 pagesTilenga ESIA Volume VI (A) - 28/02/19 - p509 To 819Total EP UgandaNo ratings yet

- Active Level 3 Unit 4Document17 pagesActive Level 3 Unit 4Alba BeatrizNo ratings yet

- Tenets of Effective Monetary Policy in The Philippines: Jasmin E. DacioDocument14 pagesTenets of Effective Monetary Policy in The Philippines: Jasmin E. DacioEmeldinand Padilla MotasNo ratings yet

- HR3 TitleI&II MemoDocument16 pagesHR3 TitleI&II MemoPeter SullivanNo ratings yet

- International Business MGMTDocument4 pagesInternational Business MGMTdevi ghimireNo ratings yet