Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Macroeconomic Analysis of A Revenue-Neutral Reduction in The Corporate Income Tax Rate Financed by An Across-The-Board Limitation On Corporate Interest Expenses

Uploaded by

BUILD Coalition0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

2K views27 pagesIn the midst of increased momentum surrounding tax reform, new research shows that limiting interest deductibility to finance a lower corporate tax rate reduces long-run economic growth. The report, which specifically examines the impact of the Wyden-Coats plan to limit the deductibility of corporate interest to its noninflationary component to finance a revenue neutral 1.5 percent reduction in the corporate income tax rate, finds:

--GDP to fall by an estimated 0.2% in the long-run or $33.6 billion in today's economy;

--Investment to fall by an estimated 0.3%, or $6 billion in today's economy; and,

--Economic welfare, measured by the value of household's consumption and leisure, to fall by an estimated 0.4%.

Original Title

Macroeconomic analysis of a revenue-neutral reduction in the corporate income tax rate financed by an across-the-board limitation on corporate interest expenses

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentIn the midst of increased momentum surrounding tax reform, new research shows that limiting interest deductibility to finance a lower corporate tax rate reduces long-run economic growth. The report, which specifically examines the impact of the Wyden-Coats plan to limit the deductibility of corporate interest to its noninflationary component to finance a revenue neutral 1.5 percent reduction in the corporate income tax rate, finds:

--GDP to fall by an estimated 0.2% in the long-run or $33.6 billion in today's economy;

--Investment to fall by an estimated 0.3%, or $6 billion in today's economy; and,

--Economic welfare, measured by the value of household's consumption and leisure, to fall by an estimated 0.4%.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

2K views27 pagesMacroeconomic Analysis of A Revenue-Neutral Reduction in The Corporate Income Tax Rate Financed by An Across-The-Board Limitation On Corporate Interest Expenses

Uploaded by

BUILD CoalitionIn the midst of increased momentum surrounding tax reform, new research shows that limiting interest deductibility to finance a lower corporate tax rate reduces long-run economic growth. The report, which specifically examines the impact of the Wyden-Coats plan to limit the deductibility of corporate interest to its noninflationary component to finance a revenue neutral 1.5 percent reduction in the corporate income tax rate, finds:

--GDP to fall by an estimated 0.2% in the long-run or $33.6 billion in today's economy;

--Investment to fall by an estimated 0.3%, or $6 billion in today's economy; and,

--Economic welfare, measured by the value of household's consumption and leisure, to fall by an estimated 0.4%.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 27

Macroeconomic analysis of a revenue-neutral

reduction in the corporate income tax rate

financed by an across-the-board limitation on

corporate interest expenses

Prepared for the BUILD Coalition

July 2013

Page 2

Executive Summary

Study:

Estimation of the long-run macroeconomic impact on the US economy from a

revenue-neutral reduction in the corporate income tax (CIT) rate financed by an

across-the-board limitation on corporate interest expenses*

Specifically, a 25% across-the-board limitation on corporate interest expenses and the

approximately 1.5 percentage-point reduction in the CIT rate it could finance are analyzed

Findings:

The net effect of this policy change would adversely affect the US economy in the

long-run**

Output is estimated to fall by 0.2% in the long-run ($33.6 billion in today's economy)

nvestment is estimated to fall by 0.3% ($6.0 billion in today's economy)

Economic welfare, measured by the value of households' consumption and their leisure, is

estimated to fall by 0.4%

Total employee compensation is estimated to fall by 0.05% ($4.7 billion in today's economy),

although employment is estimated to rise by 0.05% (0.06 million full-time equivalent employees

in today's economy) due primarily to the higher cost of investment

* For models of this type, roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of the long-run effect is generally reached within a decade.

** Estimates are long-run effects shown in relation to the size of US economy in 2013. Industry and by-state estimates are

provided in Appendix A.

Page 3

Executive Summary (cont.)

The negative impact of the limitation on corporate interest expenses more than

offsets the positive impact of the reduction in the CIT rate

The increase in the cost of investment from the limitation on corporate interest expenses

more than offsets the combined benefit of the reduction in the CIT rate and the improved

economic efficiency from the more even tax treatment by source of financing

The additional taxation from the net effect of the policy would increase the cost of

investment and decrease the return to new investment (e.g., an investment would

need to earn significantly higher returns to remain profitable)

In the corporate sector, the return to new investment would be, on average, 9.6% lower

In the business sector as a whole, the return to new investment would be, on average,

6.2% lower

Model:

The EY General Equilibrium Model of the US Economy is used to estimate the

policy impact on key macroeconomic variables in the long-run

Page 4

Table of contents

Overview of policy considerations.....................................................

Findings of macroeconomic analysis................................................

Limitations and sensitivity of analysis............................................

Appendix A: Industry and state effects.............................................

Appendix B: Structure of EY General Equilibrium Model of US

Economy...........................................................................................

5_

12

15

18

22

Page 5

A limitation on corporate interest expenses has been

included in several tax reform plans

This analysis considers the impact of a revenue-neutral reduction in

the corporate income tax rate financed by a 25% across-the-board

limitation on corporate interest expenses

A limitation on the deductibility of corporate interest expenses has

been identified as a possible source of additional revenue to help

finance a reduction in the corporate income tax (CIT) rate in several

tax reform plans

*

The Wyden-Coats tax plan proposed limiting the deductibility of corporate interest

to its noninflationary (real) component, a proposal equivalent to a 25% across-the-

board limit on interest deductibility (April 2011)

The President's Framework for Business Tax Reform identified reducing the tax

bias toward debt financing as one of four key elements for business tax reform

(February 2012)

* The Bipartisan Tax Fairness and Simplification Act of 2011, S. 727, 112

th

Cong., 1

st

Sess. (2011) and White House,

President's Framework for Business Tax Reform, February 2012.

Page 6

The bias for debt financing under the current tax system is

not due to the deductibility of interest, but primarily other

features of the US tax code

The general deductibility of corporate interest expenses applies long-

standing income tax principles that allow interest expenses to be deducted

as a legitimate business expense dating back to the inception of the

corporate income tax in 1909

The bias for debt financing under the current system is not due to the

deductibility of interest, but primarily other features of the US tax code:

The double tax on corporate profits. The double tax increases the tax on equity-financed

investments first subject to the CIT and then to shareholder level taxation on dividends or

capital gains. The double tax creates a tax bias against equity-financed investments, and

thus a tax bias for debt.

Tax-exempt investments. In pursuit of various policy objectives, Congress has chosen to

exclude or lightly tax a significant share of interest income. Such policies include not taxing

income from interest on debt held within retirement savings accounts and pension funds to

encourage retirement savings, and allowing nonprofit organizations (e.g., university

endowments) to hold debt and other investments that are largely untaxed to provide

support to the activities of this sector.

Foreign investors. Investment returns received by foreign investors are generally the

subject to tax treaties negotiated between the United States and other countries and ratified

by the Congress. These treaties generally subject investment returns, including debt

financed investments, to relatively low withholding tax rates.

Page 7

EY analysis of lower CIT rate and Wyden-Coats across-

the-board limitation on corporate interest expenses

This analysis estimates the long-run macroeconomic impact on the US

economy from a revenue-neutral reduction in the CIT rate financed by

an across-the-board limitation on corporate interest expenses*

In particular, the across-the-board limitation on corporate interest

expenses as proposed by the Wyden-Coats tax plan is analyzed:

This provision would limit the deductibility of corporate interest to its noninflationary

(real) component

Based on the historical relationship of interest rates and inflation over the past two

decades, this proposal is found to be equivalent to a roughly 25% limit on interest

deductibility

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that this provision would raise

$162.7 billion in revenue over ten years

**

This is an amount of revenue sufficient to reduce the CIT rate by roughly 1.5

percentage points within the ten-year budget window

* For models of this type, roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of the long-run effect is reached within a decade.

** Joint Committee on Taxation, "Estimated revenue effects of S. 3018, The Bipartisan Tax Fairness and Simplification

Act of 2010," November 2, 2010. Note that these estimates are for the earlier Wyden-Gregg tax plan, which included an

identical limitation on the deductibility of interest expenses.

Page 8

Policy change increases the marginal effective tax rate

(METR) on new corporate investment

A revenue-neutral reduction in the CIT rate financed by an across-

the-board limitation on corporate interest expenses has been found

to discourage investment through a higher METR a measure of the

additional economic profit needed for a new investment to cover

taxes over its life on investment*

The METR is a standard measure used to analyze investment

incentives across investment types, by source of financing and on

the overall level of investment and is frequently used to inform tax

policy discussions:

For example, see President's Framework for Business Tax Reform (2012),

Congressional Research Service (2011), Treasury Competitiveness Report

(2007), Congressional Budget Office (2005), 2005 Bush Tax Panel, 2000 Treasury

Depreciation Study and 1986 Tax Reform Act analyses**

* Robert Carroll and Tom Neubig, Business Tax Reform and the Tax Treatment of Debt: Revenue neutral rate reduction financed by an across-the-board interest

deduction limit would deter investment, An Ernst & Young LLP report prepared on behalf of the PEGCC, May 2012.

** White House, President's Framework for Business Tax Reform, February 2012; Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples, Tax Rates and Economic Growth, December

5, 2011; US Department of the Treasury, Approaches to Improve the Competitiveness of the U.S. Business Tax System for the 21

st

Century, December 20, 2007;

Congressional Budget Office, Taxing Capital Income: Effective Rates and Approaches to Reform, October 1, 2005; The President's Advisory Panel on Federal Tax

Reform, Simple, Fair, & Pro-Growth: Proposals to Fix America's Tax System, November 1, 2005; US Department of the Treasury, Report to the Congress on Depreciation

Recovery Periods and Methods, July 2000; James B. Mackie, (2002), "Unfinished Business of the 1986 Tax Reform Act: An Effective Tax Rate Analysis of Current Issues

in the Taxation of Capital ncome, National Tax Journal, Vol. 45(2), June, pp. 293-337.

Page 9

CIT rate reduction and across-the-board limitation on

corporate interest expenses impacts US economy in two ways

The net effect of the policy change in 2013 would be to increase the

marginal effective tax rate (METR) for new investment in the corporate

sector by 9.6% and in the business sector as a whole by 6.2%, thus

discouraging investment

This METR implies that the return to a new investment in the corporate sector would be,

on average, 9.6% lower and in the business sector as a whole, on average, 6.2% lower

due to the additional taxation from the net effect of the policy

A revenue-neutral reduction in the CIT tax rate financed by a limitation on

corporate interest expenses promotes a more efficient allocation of

capital in the US economy by moving toward a more level tax playing

field between debt and equity

The METR for a debt-financed investment would rise from 0.4% to 17.7%, but would

remain largely unchanged for an equity-financed investment (falling from 38.8% to

37.6%)

This policy also further discourages investment in the corporate sector

The METR for new corporate investment would increase from 29.2% to 32.0%, but

would remain unchanged at 24.8% for noncorporate investment*

* The noncorporate sector is defined here to include businesses organized as partnerships, S corporations, limited liability companies,

and sole proprietorships.

Page 10

Effect of CIT rate reduction and across-the-board limitation

on corporate interest expenses on METRs in 2013

Current law Proposal % change

Business sector 27.6% 29.3% 6.2%

Corporate sector 29.2% 32.0% 9.6%

Equipment 20.0% 23.7% 18.5%

Structures 25.8% 29.0% 12.4%

Land 39.7% 41.8% 5.3%

Inventories 37.8% 39.3% 4.0%

Debt finance 0.4% 17.7% N/A

Equity finance 38.8% 37.6% -3.1%

Noncorporate sector 24.8% 24.8% 0.0%

Equipment 14.4% 14.4% 0.0%

Structures 20.6% 20.6% 0.0%

Land 37.1% 37.1% 0.0%

Inventories 34.3% 34.3% 0.0%

Owner-occupied housing -2.4% -2.4% 0.0%

Economy-wide 20.0% 21.3% 6.5%

Source: Ernst & Young LLP.

Page 11

EY General Equilibrium Model of the US Economy

The EY General Equilibrium Model of the US Economy is used to

analyze the long-run impact of this revenue-neutral policy change on

the US economy*

The macroeconomic impacts are measured by changes in:

Output, investment, capital stock, labor supply, employment and after-tax wages,

as well as industry-specific effects

The impact of the policy change throughout US economy is estimated

The policy change initially affects the METR for new investment in the corporate

sector

This change ripples throughout the economy until after-tax returns are equalized

This policy change is revenue neutral and, as a result, there is no

need for a countervailing change in fiscal policy (e.g., a change in

government spending or revenues)

* For models of this type, roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of the long-run effect is generally reached within a decade.

Page 12

Net effect of interest limitation and lower CIT rate would

adversely affect the US economy in the long-run

This analysis finds that, on net, a revenue-neutral reduction in the CIT

rate financed by an across-the-board limitation on corporate interest

expenses would adversely affect the US economy in the long-run*

Output is estimated to fall by 0.2% in the long-run ($33.6 billion in today's economy)

nvestment is estimated to fall by 0.3% ($6.0 billion in today's economy)

Economic welfare, measured by the value of households' consumption and their

leisure, is estimated to fall by 0.4%

Total employee compensation is estimated to fall by 0.05% ($4.7 billion in today's

economy), although employment is estimated to rise by 0.05% (0.06 million full-

time equivalent employees in today's economy) due primarily to the higher cost of

investment

The increase in the cost of investment from the limitation on corporate

interest expenses more than offsets the combined benefit of the

reduction in CIT rate and the efficiency benefit from a more even tax

treatment by source of financing

* Estimates are long-run effects shown in relation to the size of US economy in 2013. These estimates are available by

industry and by state in Appendix A.

Page 13

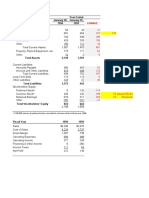

% change

from

current law

Change from

current law

($billions at

2013 levels)

*

Output -0.21% -$33.6

Consumption -0.20% -$23.0

Investment -0.28% -$6.0

Capital stock -0.85% -$421.4

Employee compensation -0.05% -$4.7

Employment (1,000s) 0.05% 60

Total welfare -0.41% N/A

Long-term macroeconomic impacts of a revenue-neutral

reduction in the CIT rate financed by a 25% across-the-board limit

on corporate interest deductions

Long-term macroeconomic impact

* Amounts are the estimated long-run impacts, but expressed at 2013 levels. Generally, in models of this type, roughly two-thirds

to three-quarters of the long-run effect is generally reached within a decade. The estimated employment effects are positive

because of the substitution of labor for capital associated with the higher cost of investment.

Page 14

Long-term macroeconomic impact (cont.)

The revenue-neutral tax policy change of a lower CIT rate financed by

a 25% across-the-board limitation on corporate interest deductions

results in a 0.21% decrease in the long-run US output*

Due to the decrease in the relative price of labor to capital, this tax

policy change results in an increase in labor intensity throughout the

US economy

This substitution of labor for capital results in an increase in long-run employment

of 0.05%, but a 0.05% decrease in long-run after-tax compensation due to a lower

long-run after-tax wage (i.e., more hours are worked for a lower wage)

Total welfare, an abstract measure of the well-being of US

households equivalent to the value of their consumption and leisure,

is estimated to fall by 0.4%

* For models of this type, roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of the long-run effect is generally reached within a decade.

Page 15

Assumptions and limitations of analysis

Any modeling effort is only a rough approximation to reality, and the modeling in this report is no

exception. Although many caveats might be added to the analysis, several are particularly

noteworthy:

Estimates based on stylized depiction of the US economy. The general equilibrium

model used for this analysis is, by its very nature, a highly stylized depiction of the US

economy intended to capture key details important to the effects of a tax policy change

US on a fiscally sustainable path. The model assumes the United States is on a fiscally

sustainable path under current law and remains on a fiscally sustainable path after the policy

change, when neither may necessarily be the case

Wyden-Coats interest limitation depicted by historical relationship. The Wyden-Coats

across-the-board corporate interest limitation is approximated by the historical relationship of

inflation and interest rates. The actual limitation would depend on the future trends in both

inflation and interest rates

Estimates limited by calibration. This model is calibrated to the recent US economy and,

because any particular year contains unique events, no particular baseline year is completely

generalizable

Based on preliminary JCT revenue estimate. The revenue-neutral policy change in the

CIT rate and the across-the-board limitation on corporate interest expenses is based on

preliminary revenues estimates of these provisions by the JCT

Page 16

The results reported above depend, in part, upon how sensitive households and

businesses are to changes in tax policy, in particular the degree to which tax policy

influences the decision to save or spend and the decision between labor or leisure

Because there is some degree of uncertainty in exactly what household parameter

values should be used, a base case suggested by the economic literature was utilized

and scenarios with lower and higher responsiveness were assumed to show the

sensitivity of the results to the underlying assumptions

Sensitivity of the results

% change from current law

Base Low High

Output -0.21% -0.20% -0.21%

Consumption -0.20% -0.20% -0.21%

Investment -0.28% -0.26% -0.31%

Capital stock -0.85% -0.83% -0.86%

Employee compensation -0.05% -0.05% -0.06%

Employment 0.05% 0.05% 0.04%

Total welfare -0.41% -0.39% -0.42%

Note: Parameter values used in the base, low and high responsiveness scenarios are provided in Appendix B.

Page 17

Sensitivity of the results

Appendix

Page 18

Appendix A: Industry-specific macroeconomic output

effects

Note: Estimates are long-run effects shown in relation to the size of US economy in 2013.

Long-run change

in output

(%)

Long-run change

in output

($million)

Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting -0.13% -$250

Mining, quarrying and oil and gas extraction -0.13% -400

Utilities -0.01% -30

Construction -0.26% -1,470

Manufacturing -0.19% -3,760

Wholesale and retail trade -0.25% -4,830

Transportation and warehousing -0.21% -980

Information -0.10% -720

Finance, insurance and real estate -0.01% -270

Business services -0.25% -5,130

Non-business services -0.25% -6,110

Total change in business sector output: -$23,950

Page 19

Appendix A: Industry-specific macroeconomic

compensation effects

Long-run change

in compensation

(%)

Long-run change

in compensation

($million)

Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting -0.01% -$10

Mining, quarrying and oil and gas extraction 0.07% 60

Utilities 0.13% 110

Construction -0.13% -510

Manufacturing 0.01% 130

Wholesale and retail trade -0.11% -1,080

Transportation and warehousing -0.07% -190

Information 0.07% 190

Finance, insurance and real estate 0.22% 1,420

Business services -0.09% -1,260

Non-business services -0.09% -1,560

Total change in business sector compensation: -$2,710

Note: Estimates are long-run effects shown in relation to the size of US economy in 2013.

Page 20

Appendix A: Long-run state-by-state output effects

$million $million

United States -$33,620 Missouri -570

Alabama -400 Montana -90

Alaska -110 Nebraska -210

Arizona -580 Nevada -290

Arkansas -240 New Hampshire -140

California -4,360 New Jersey -1,100

Colorado -590 New Mexico -180

Connecticut -490 New York -2,490

Delaware -130 North Carolina -980

District of Columbia -270 North Dakota -90

Florida -1,730 Ohio -1,100

Georgia -950 Oklahoma -350

Hawaii -160 Oregon -440

Idaho -130 Pennsylvania -1,310

Illinois -1,510 Rhode Island -110

Indiana -620 South Carolina -390

Iowa -320 South Dakota -90

Kansas -290 Tennessee -630

Kentucky -380 Texas -2,880

Louisiana -540 Utah -280

Maine -120 Vermont -60

Maryland -700 Virginia -1,000

Massachusetts -880 Washington -800

Michigan -880 West Virginia -150

Minnesota -630 Wisconsin -570

Mississippi -230 Wyoming -80

Note: Estimates are long-run effects shown in relation to the size of US economy in 2013. Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Page 21

Appendix A: Long-run state-by-state compensation

effects

$million $million

United States -$4,700 Missouri -90

Alabama -60 Montana -10

Alaska -20 Nebraska -30

Arizona -90 Nevada -50

Arkansas -40 New Hampshire -20

California -600 New Jersey -150

Colorado -90 New Mexico -30

Connecticut -40 New York -190

Delaware -10 North Carolina -140

District of Columbia -70 North Dakota -10

Florida -270 Ohio -170

Georgia -140 Oklahoma -50

Hawaii -30 Oregon -60

Idaho -20 Pennsylvania -190

Illinois -200 Rhode Island -20

Indiana -80 South Carolina -60

Iowa -30 South Dakota -10

Kansas -40 Tennessee -90

Kentucky -60 Texas -370

Louisiana -70 Utah -40

Maine -20 Vermont -10

Maryland -130 Virginia -190

Massachusetts -120 Washington -120

Michigan -130 West Virginia -20

Minnesota -80 Wisconsin -70

Mississippi -40 Wyoming -10

Note: Estimates are long-run effects shown in relation to the size of US economy in 2013. Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Page 22

Appendix B: Overview of the EY General Equilibrium

Model of US Economy

Tax policy affects the incentives to work, to save and invest, to

allocate capital and labor among competing uses and for households

to consume different mixes of consumption goods

Industries can substitute between capital and labor, and in an open

economy, international capital flows between the US economy and

the rest of the world

Capital responds to differences in the after-tax return to capital by

substituting between sectors (i.e., corporate, noncorporate),

industries, and type of financing (i.e., debt, equity)

Model includes 4 sectors (corporate, noncorporate, owner-occupied

housing and government), 13 industries and 76 asset types

Page 23

Appendix B: Overview of the EY General Equilibrium

Model of US Economy (cont.)

Differences between industries are explicitly modeled

Treatment under the tax code such as through the treatment of inventories (i.e.,

LIFO and FIFO) and the domestic production deduction

Types of assets (i.e., different mixes of equipment, structures, inventories and land)

and their treatment in regard to tax depreciation deductions

Mix of capital and labor across industries

The concentration of corporate and noncorporate legal forms across industries

The varying role of debt and equity in financing investments across industries

Elasticity of substitution between capital and labor

Industry output required in final use consumption goods

The model generally follows the framework of Ballard, Fullerton,

Shoven and Whalley (1985) and Fullerton and Henderson (1989)

Page 24

Appendix B: Debt and equity in the EY General

Equilibrium Model of US Economy

There is an extensive economic literature on capital structures which

note that, while there is a deduction for interest, there is not a

deduction for dividends or retained earnings

An International Monetary Fund (2011) working paper performed a

meta analysis of this literature to provide a "consensus estimate of

this effect based on 267 estimates across 19 different studies

The IMF paper reports a tax elasticity of debt between 0.5 and 0.7 (i.e., a one

percentage point increase in the CIT rate will result in a 0.5 to 0.7 percent increase

in leverage)

In this model, each of the 13 industries tradeoff between the use of

debt and equity to finance investments based on an elasticity of 0.6

* Ruud A. de Mooij, (2011), "The Tax Elasticity of Corporate Debt: A Synthesis of Size and Variations, nternational

Monetary Fund, Working Paper, WP-11-95.

Page 25

Appendix B: Structure of EY General Equilibrium Model

of the US Economy

The EY General Equilibrium Model of the US Economy works through

a nested utility function with eight distinct layers

(1) Households choose between present consumption and future consumption (i.e.,

savings). Savings become real capital in the next time period of the model

(2) Households choose what portion of their labor endowment is used for work (and

thereafter spent on consumption goods) and what portion to consume as leisure

(3) Households choose what mix of 15 consumption goods to purchase with the

income earned from working

(4) Each consumption good is a fixed coefficient mix of 13 industry, owner-occupied

housing and government outputs (i.e., producer goods)

(5) The producer goods are a fixed proportion of value added and intermediate

goods

Page 26

Appendix B: Structure of EY General Equilibrium Model

of the US Economy (cont.)

(6) Value added within each industry is an endogenous mix of capital and labor

(7) Industries choose an endogenous mix of the corporate and noncorporate legal

forms subject to their preferences and cost minimization

(8) Within each legal form, industries choose an endogenous mix of debt-financed

investment and equity-financed investment subject to their preferences and cost

minimization

A general equilibrium framework solves for equilibrium prices in factor

(i.e., capital and labor) and goods markets while simultaneously

taking into account the behavioral responses of individuals and

businesses to the changes in tax policy

That is, each of these 8 nests are solved simultaneously

Key parameter values are provided in the table below

Page 27

Appendix B: Key model parameters

Sensitivity

Base Low High

Household present consumption versus savings decision

Elasticity of substitution (CES) 1.70 1.50 1.90

Present consumption weight 0.75 0.60 0.90

Household labor versus leisure decision

Elasticity of substitution (CES) 0.80 0.70 0.90

Leisure weight* 0.10 0.14 0.07

Industry elasticity of substitution between debt and equity 0.60 0.50 0.70

Baseline financing of business investment by source

Debt-financed investment 35% 35% 35%

Equity-financed investment 65% 65% 65%

Retained earnings 65% 65% 65%

New shares 35% 35% 35%

Corporate investment 63% 63% 63%

Noncorporate investment 37% 37% 37%

Industry capital-labor elasticity of substitution

Maximum elasticity 0.80 0.80 0.80

Minimum elasticity 0.50 0.50 0.50

* This parameter is adjusted such that the baseline factor markets are comparable across the base, low and high scenarios.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Three Approaches to Economic Analysis of ProjectsDocument25 pagesThree Approaches to Economic Analysis of ProjectsRodrick WilbroadNo ratings yet

- ASHLAWN - Complaint Against City of Painesville (FILED)Document28 pagesASHLAWN - Complaint Against City of Painesville (FILED)The News-HeraldNo ratings yet

- Valuation With Multiples A Conceptual AnalysisDocument13 pagesValuation With Multiples A Conceptual AnalysisAndersson SanchezNo ratings yet

- Dell Case AnswersDocument13 pagesDell Case AnswersMine SayracNo ratings yet

- QUIZ7 Audit of LiabilitiesDocument3 pagesQUIZ7 Audit of LiabilitiesCarmela GulapaNo ratings yet

- SM1001906 - Chapter 4 (SI CI)Document12 pagesSM1001906 - Chapter 4 (SI CI)Shubham PriyamNo ratings yet

- Economic Impact of Tribal GamingDocument2 pagesEconomic Impact of Tribal GamingKJZZ PhoenixNo ratings yet

- Macro Environmental FactorsDocument2 pagesMacro Environmental FactorsRellie CastroNo ratings yet

- ESOP Calculator IndiaDocument2 pagesESOP Calculator IndiajdonNo ratings yet

- Teuer FurnitureDocument35 pagesTeuer FurniturePawanDubeyNo ratings yet

- Samsung C&T 2014 Financial StatementsDocument126 pagesSamsung C&T 2014 Financial StatementsJinay ShahNo ratings yet

- Phdthesis Hum Aditi 2012Document213 pagesPhdthesis Hum Aditi 2012Rahul SavaliaNo ratings yet

- JPM Nikkei - USDJPY Correlation To BRDocument4 pagesJPM Nikkei - USDJPY Correlation To BRraven797No ratings yet

- Arbitrage Trade Analysis of Stock Trading in NSE and BSE MBA ProjectDocument86 pagesArbitrage Trade Analysis of Stock Trading in NSE and BSE MBA ProjectNipul Bafna100% (3)

- CPX Admin 11122Document198 pagesCPX Admin 11122sen2natNo ratings yet

- 4-ARPSE 2012-13 Dated April 01, 2013 PDFDocument505 pages4-ARPSE 2012-13 Dated April 01, 2013 PDFarshadNo ratings yet

- Socialight: H-No:8-2-703/4/1, 1st Floor, Sai Enclave, Bhola Nagar, Road No:12, Banjarahills, Hyderabad-500034Document4 pagesSocialight: H-No:8-2-703/4/1, 1st Floor, Sai Enclave, Bhola Nagar, Road No:12, Banjarahills, Hyderabad-500034subba reddyNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document8 pagesAssignment 2chandu1113100% (2)

- TESCO Share Fundamentals (TSCO) - London Stock ExchangeDocument5 pagesTESCO Share Fundamentals (TSCO) - London Stock ExchangeinuNo ratings yet

- Samsung Cash Flow and Fund Flow2Document14 pagesSamsung Cash Flow and Fund Flow2Suhas ChowdharyNo ratings yet

- Accounting 5Document8 pagesAccounting 5khurramNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Module 5 Analysis and Interpretation of Financial StatementsDocument31 pagesWeek 6 Module 5 Analysis and Interpretation of Financial StatementsZed Mercy86% (14)

- SMB2F2 2Document183 pagesSMB2F2 2Bajaj BhagyashreeNo ratings yet

- Management Advisory Services ExamDocument12 pagesManagement Advisory Services ExamCiatto SpotifyNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow StatementDocument11 pagesCash Flow StatementDuke CyraxNo ratings yet

- Privatization in BanksDocument68 pagesPrivatization in Bankstanima_10660750% (4)

- Ratio Analysis of Berger PaintsDocument17 pagesRatio Analysis of Berger PaintsUtsav Dubey0% (1)

- How To Start Your Own BusinessDocument10 pagesHow To Start Your Own BusinessZakaria Encg100% (1)

- QUIZ #3: BREAKEVEN ANALYSIS FOR COST AND REVENUE FUNCTIONSDocument2 pagesQUIZ #3: BREAKEVEN ANALYSIS FOR COST AND REVENUE FUNCTIONSJolina AynganNo ratings yet