Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Exponential Equation

Uploaded by

bobbysingersyahooOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Exponential Equation

Uploaded by

bobbysingersyahooCopyright:

Available Formats

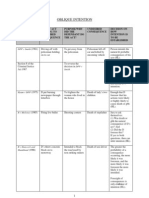

consti grapilon Rules of exponents A Review of the Operations of the Voting Section of the Civil Rights ...

ANGARA V ELECTORAL COMMISSION Angara v. Electoral Commission Peo v Vera YNOT VS IAC SALONGA VS CRUZ PANO JAVIER V COMELEC Supremacy PEOPLE V VERA Summary: People vs. Vera justiciability heard the application of Cu Unjieng for probation in the aforesaid criminal cas e Political Question Accused is informed why he is proceeded against. Held: YES. The unchallenged rul e is that the person who impugns the validity of a statute must have a personal and substantial interest in the case such that he has sustained. Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial Review Ynot vs. IAC justiciability Section 5 [2] (a), the decision of lower courts declaring a law unconstitutiona l is subject to review by the Supreme Court Political Question Accused is informed why he is proceeded against. Held: YES. The unchallenged rul e is that the person who impugns the validity of a statute must have a personal and substantial interest in the case such that he has sustained. Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial Review Ynot vs. IAC justiciability Section 5 [2] (a), the decision of lower courts declaring a law unconstitutiona l is subject to review by the Supreme Court Political Question Accused is informed why he is proceeded against. Held: YES. The unchallenged rul e is that the person who impugns the validity of a statute must have a personal and substantial interest in the case such that he has sustained. Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial Review Ynot vs. IAC

justiciability Section 5 [2] (a), the decision of lower courts declaring a law unconstitutiona l is subject to review by the Supreme Court Political Question Facts: Executive Order No. 626-A prohibited the transportation of carabaos and carabeef from one province to another. Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial Review Salonga v Cruz Pano justiciability FACTS: A rash of bombings occurred in the Metro Manila Political Question Facts: one Victor Burns Lovely, Jr., a Philippine-born American citizen killed himself and injured his younger brother, Romeo, as a result of the explosion of a small bomb inside his room at the YMCA building Found in Lovely's possession b y police and military authorities were several pictures taken at the birthday pa rty of former Congressman Raul Daza held at the latter's residence in a Los Ange les suburb.Mr. Lovely and his two brothers, Romeo and Baltazar Lovely where char ged with subversion, illegal possession of explosives, and damage to property.. Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial Review Salonga v Cruz Pano justiciability Bombs once again exploded in Metro Manila including one which resulted in the d eath of an American lady who was shopping at Rustan's The next day, newspapers c ame out with almost identical headlines stating in effect that Salonga had been linked to the various bombings in Metro Manila.Within the next 24 hours, arrest, search, and seizure orders (ASSOs) were issued against persons, including Salon ga, who were apparently implicated by Victor Lovely Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial Review Javier v Comelec Seven suspects, including respondent Pacificador, are now facing trialfor these murders. Conceivably, it intimidated voters against supporting theOpposition can didate or into supporting the candidate of the ruling party. Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial Review Javier v Comelec Seven suspects, including respondent Pacificador, are now facing trialfor these murders. Conceivably, it intimidated voters against supporting theOpposition can didate or into supporting the candidate of the ruling party. Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial Review Salonga v Cruz Pano justiciability Bombs once again exploded in Metro Manila including one which resulted in the d eath of an American lady who was shopping at Rustan's The next day, newspapers c ame out with almost identical headlines stating in effect that Salonga had been linked to the various bombings in Metro Manila.Within the next 24 hours, arrest, search, and seizure orders (ASSOs) were issued against persons, including Salon

ga, who were apparently implicated by Victor Lovely Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial ReviewKILOSBAYAN vs. MANUEL L. MORATO are the same but the cases are not. RULE ON CONCLUSIVENESS cannot still apply. An issue actually and directly passed upon and determine in a former suit cannot again be drawn in question in any future action between the same parties involv ing a different cause of action. But the rule does not apply to issues of law at least when substantially unrelated claims are involved. When the second proceed ing involves an ia Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial ReviewKILpeo v ferrer Facts: Hon. Judge Simeon Ferrer is the Tarlac trial court judge that declared RA 1700 or the Anti-Subversive Act of 1957 as a bill of attainder. Thus, dismissing the information of subversion against the following: 1.) Feliciano Co for being an officer/leader of the Communist Party of the Philippines 1.) The Congress u surped the powers of the judge Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial ReviewKILpeo v ferrer 2.) Assumed judicial magistracy by pronouncing the guilt of the CPP without any forms of safeguard of a judicial trial. 3.) It created a presumption of organiza tional guilt by being members of the CPP regardless of voluntariness. Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial ReviewKILpeo v ferrer Held: The court holds the VALIDITY Of the Anti-Subversion Act of 1957. A bill of attainder is solely a legislative act. It punishes without the benefit of the trial. It is the substitution of judicial determination to a legislative determination of guilt. In order for a statute be measured as a bill of attaind er, the following requisites must be present: 1.) The statute specifies persons, groups. 2.) the statute is applied retroactively and reach past conduct. (A bil l of attainder relatively is also an ex post facto law.) Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial ReviewKILBAYAN v. ZAMORA A party bringing a suit challenging the constitutionality of a law, act Facts: The United States panel met with the Philippine panel to discussed, among others , the possible elements of the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA). This resulted to a series of conferences and negotiations which culminated Supremacy The Exercise of Judicial ReviewKILBAYAN v. ZAMORA ISSUE: Is the VFA governed by the provisions of Section 21, Art VII or of Sectio n 25, Article XVIII of the Constitution? HELD: Section 25, Article XVIII, which specifically deals with treaties involving fore ign military bases, troops or facilities should apply in the instant case. To a certain extent and in a limited sense, however, the provisions of section 21, Ar ticle VII will find applicability with regard to the issue and for the sole purp ose of determining the number of votes required Supremacy Estrada pardon barred him from running Estrada pardon barred him from running, lawyers say Former president Joseph Estrada

Two private lawyers on Tuesday asked the Sandiganbayan to clarify whether or not the presidential pardon given to former president Joseph Estrada after his conv iction for plunder in 2007 allowed him to run for elective office. Estrada, who ran but lost a presidential bid in 2010, has again filed a certifi cate of candidacy this time for mayor of Manila.

Supremacy Estrada pardon barred him from running In A Motion for Determination and Interpretation of Judgment in the Plunder Case in Relation to the Conditional Pardon, lawyers Fernando Perito and Nepthali Alipo sa said Estrada may have violated the conditions of the pardon granted by then president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo when he decided to again seek elective positio n or office. Supremacy Estrada pardon barred him from running to no longer seek any elective position or office. Hence, the pardon did not resto re his right to run for any elective office. Furthermore, the Sandiganbayans imposition of the accessory penalty of perpetual a bsolute disqualification from holding public office was not expressly erased by t he pardon.

Supremacy Comelec warns vs. double-registrants Javier vs. COMELEC JAVIER VS. COMELEC G.R. No.L- 68379-812, September 22, 1986 FACTS: 1. The petitioner Evelio Javier and the private respondent Arturo Pacificador were candidates in Antique for the Batasang Pambansa election in May 1984; 2. Alleging serious anomalies in the conduct of the elections and the canvass of the election returns, Javier went to the COMELEC to prevent the impending pro clamation of his rival; 3. On May 18, 1984, the S

Supremacy Comelec warns vs. double-registrants Javier vs. COMELEC JAVIER VS. COMELEC G.R. No.L- 68379-812, September 22, 1986 FACTS: second Division of the COMELEC directed the provincial board of canvassers to pr oceed with the canvass but to suspend the proclamation of the winning candidate

until further orders; 4. On June 7, 1984, the same Second Division ordered the board to immediately convene and to proclaim the winner without prejudice to the outcome of the petit ion filed by Javier with the COMELEC;

Supremacy Comelec warns vs. double-registrants Javier vs. COMELEC JAVIER VS. COMELEC G.R. No.L- 68379-812, September 22, 1986 FACTS: second Division of the COMELEC directed the provincial board of canvassers to pr oceed with the canvass but to suspend the proclamation of the winning candidate until further orders; 4. On June 7, 1984, the same Second Division ordered the board to immediately convene and to proclaim the winner without prejudice to the outcome of the petit ion filed by Javier with the COMELEC;

Supremacy Comelec warns vs. double-registrants Javier vs. COMELEC JAVIER VS. COMELEC G.R. No.L- 68379-812, September 22, 1986 FACTS: ISSUE: Was the Second Division of the COMELEC, authorized to promulgate its decision of July 23, 1984 proclaiming Pacificador the winner in the election ? APPLICABLE PROVISIONS OF THE CONSITUTION: The applicable provisions of the 1973 Constitution are Art. XII-C, secs. 2 and 3 , which provide:

Supremacy Comelec warns vs. double-registrants Javier vs. COMELEC JAVIER VS. COMELEC G.R. No.L- 68379-812, September 22, 1986 FACTS: Section 2. Be the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns an d qualifications of all members of the Batasang Pambansa and elective provincial

and city officials.

Supremacy Randy David Vs. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo In Congress

Facts : On February 24, 2006, as the nation celebrated the 20th Anniversary of E dsa People Power I, President Arroyo issued PP 1017 declaring a state of nationa l emergency. Chief of Staff Michael Defensor announced that warrantless arrest and take-over o f facilities, including media, can already be implemented Undeterred by the announcements that rallies and public protest would not be all owed, members of Kilusang Mayo Uno and National Federation of Labor Unions, marc hed. During the dispersal of the rallyist along EDSA, Supremacy Randy David Vs. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo In Congress

Facts : Police arrested without warrant petitioner Randolf S. David, a Proffesor of the University of the Philippines and newspaper columnist. Also arrested was his co mpanion, Ronald Llamas, president of party-list Akbayan. Issue: Whether the issuance of PP 1017 is Constitutional, Whether the provision of PP 1017 commanding the AFP to enforce laws not related to lawless violence, a s well as decrees promulgated by the President, and provision declaring national emergency under section 17, article VII of the Supremacy Randy David Vs. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo In Congress

Facts : Constitution is Constitutional. Whether G.O. No. 5 is Constitutional Whether th e dispersal and warrantless arrest, the warrantless search are Constitutional. Held: PP 1017 is constitutional insofar as it constitute a call by the President for the AFP to prevent or suppress Lawless violence. The proclamation is sustain ed by section 18, article VII of the constitution. However, PP 1017s extraneous p rovisions giving the President express or implied power to issue decrees to dire ct AFP to Supremacy Randy David Vs. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo In Congress

Facts : enforce obedience to all laws even those not related to lawless violence as dec rees promulgated by the President; and to impose standards on media or any form of prior restraint on the press, are ultra vires and unconstitutional. The Court also rules that under section 17, article XII of the constitution, the Presiden t, in the absence of a legislation, cannot take over privately-owned public util ity and private business affected with public interest. Supremacy

bAGONG ALYANSANG MAKABAYAN ET AL V ERMITA

Facts : Bayan members assembled at Plaza Ferguson in Ermita, Manila several meters away from the US embassy Respondent Lance Corporal (L/CPL) Daniel Smith is a member of the United St ates Armed Forces. He was charged with the crime of rape committed against a Fi lipina, petitioner herein, sometime on November 1, 2005 Supremacy bAGONG ALYANSANG MAKABAYAN ET AL V ERMITA

Facts : Pursuant to the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) between the Republic of the Phi lippines and the United States, entered into on February 10, 1998, the United St ates, at its request, was granted custody of defendant Smith pending the proceed ings. Supremacy bAGONG ALYANSANG MAKABAYAN ET AL V ERMITA

iSSUES:: Pursuant to the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) between the lippines and the United States, entered into on February 10, ates, at its request, was granted custody of defendant Smith ings. Petitioners contend that the Philippines should have custody Supremacy bAGONG ALYANSANG MAKABAYAN ET AL V ERMITA

Republic of the Phi 1998, the United St pending the proceed of defendant L/CPL

The fact that the VFA was not submitted for advice and consent of the United Sta tes Senate does not detract from its status as a binding international agreement or treaty recognized by the said State. For this is a matter of internal Unite d States law Notice can be taken of the internationally known practice by the U nited States of submitting to its Senate for advice and consent agreements that are policymaking in nature, whereas those that carry out or further implement th ese policymaking agreements are merely Supremacy bAGONG ALYANSANG MAKABAYAN ET AL V ERMITA

submitted to Congress, under the provisions of the so-called CaseZablocki Act, wi thin sixty days from ratification.

Supremacy bAGONG ALYANSANG MAKABAYAN ET AL V ERMITA

submitted to Congress, under the provisions of the so-called CaseZablocki Act, wi thin sixty days from ratification. The second reason has to do with the relation between the VFA and the RP-US Mutual Defense Treaty of August 30, 1951. This earlier agreement was signed an d duly ratified with the concurrence of both the Philippine Senate and the Unite d States Senate Supremacy DEFENSOR-SANTIAGO, et al. Vs. COMELEC

Is there a law which would provide for the mechanism for the people to propose amendments to the Constitution by peoples initiative? While Congress had enacted RA 6735 purportedly to provide the mechanisms for the peoples exercise the power to amend the Constitution by peoples initiative, t he Supreme Court in MIRIAM Supremacy DEFENSOR-SANTIAGO, et al. Vs. COMELEC

DEFENSOR-SANTIAGO, et al. Vs. COMELEC, G.R. No. 127325, March 19, 1997 & J une 10, 1997, the Supreme Court held that RA 6735 is incomplete, inadequate or w anting in essential terms and conditions insofar as initiative on amendments to the Constitution is concerned. Its lacunae on this substantive matter are fatal and cannot be cured by empowering the COMELEC to promulgate such rules and regulat ions as may be necessary to carry the purposes of this act. Supremacy LIM V EXEC SECRETARY

FACTS : Beginning 2002, personnel from the armed forces of the United States started arr iving in Mindanao, to take part, in conjunction with the Philippine military, in Balikatan 02-1. In theory, they are a simulation of joint military maneuvers purs uant to the Mutual Defense Treaty, a bilateral defense agreement entered into by the Philippines and the United States in 1951. Supremacy LIM V EXEC SECRETARY

On Feb. 2002, Lim filed this petition for certiorari and prohibition, praying t hat respondents be restrained from proceeding with the so-called Balikatan 02-1, a nd that after due notice and hearing, judgment be rendered issuing a permanent w rit of injuction and/or prohibition against the deployment of US troops in Basil an and Mindanao for being illegal and in violation of the Constitution. Petitioners contend that the RP and the US signed the Mutual Defense Treaty to provide mutual military assistance in acc ordance with the constitutional processes of each country only in the case of a ar med attack by an external aggressor, meaning a third country, against one of the m. They further argued that it cannot be said that the Abu Sayyaf in Basilan con stitutes an external aggressor to warrant US military assistance in accordance w ith MDT of 1951. Another contention was that the VFA of 1999 does not authorize American soldiers to engage in combat operations in Philippine territory. ISSUE : Whether or not the Balikatan 02-1 activities are covered by the VFA. RULING : Petition is dismissed. The VFA itself permits US personnel to engage on an imper manent basis, in activities, the exact meaning of which is left undefined. The sol e encumbrance placed on its definition is couched in the negative, in that the U S personnel must abstain from any activity inconsistent with the spirit of this a greement, and in particular, from any political activity.

Francisco vs. House of Representatives, GR 160261, Nov. 10, 2003 FRANCISCO VS. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Case Digest FRANCISCO VS. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES G.R. NO. 160261 NOV. 10, 2003 Facts: On 28 November 2001, the 12th Congress of the House of Representatives ad opted and approved the Rules of Procedure in Impeachment Proceedings, supersedin g the previous House Impeachment Rules approved by the 11th Congres sabi... insufficient in substance second impeachment complaint was accompanied by a"Resolution of Endorsement/Impe achment" signed by at least 1/3 of all the Member ISSUE: Section 5 of Article XI of the Constitution that "[n]o impeachment proceedings s hall be initiated against the same official more than once within a period of on e year." HELD: While the U.S. Constitution bestows sole power of impeachment to the House of Re presentatives without limitation, our Constitution, though vesting in the House of Representatives the exclusive power to initiate impeachment cases, provides f or several limitations Francisco vs. House of Representatives, GR 160261, Nov. 10, 2003 FRANCISCO VS. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Case Digest

These limitations include the manner of filing , required vote to impeach,and the one year bar on the impeachment of one and th e same official. Finally, there exists no constitutional basis for the contention that the exerci se of judicial review over impeachment proceedings would upset the system of che cks and balances. Verily, the Constitution is to be interpreted as a whole Manila Prince Hotel vs. GSIS Petitioner: Manila Prince Hotel Respondent: Government Service Insurance System (GSIS), Facts: - The shares (31% to 50%) of Manila Hotel Corporation were sold by GSIS through public bidding. - There were two Manila Prince Hotel vs. GSIS bidders Manila Prince Hotel Corporation (Filipino firm) and Renong Berhad (Malay sian firm) - Renong Berhad bade higher than - Pending the declaration of Renong Berhad as the highest bidder, MPHC sent a ma nagers check amounting to the same bid by RB. - GSIS refused to Manila Prince Hotel vs. GSIS accept offer. - Petitioner prayed for writ of mandamus and prohibition. Lower court issued a r estraining order preventing GSIS and Renong Berhad from consummating the sale. - Pending the declaration of Renong Berhad as the highest bidder, MPHC sent a ma nagers check amounting to the same bid by RB. - GSIS refused to Supremacy LAMIBINO ET AL V COMELEC

Facts: Petitioners (Lambino group)commenced gathering signatures for an initiati ve petition to change the 1987 constitution, they filed a petition with the COME LEC to hold a plebiscite that will ratify their initiative petition under RA 673 5. Lambino group alleged that the petition had the support of 6M individuals ful filling what - Invoked by petitioners: Section 10 of Article XII. The Congress shall, upon re commendation of the economic and planning agency, when the national interest dic tates, reserve to citizens of the Philippines or to corporations or associations at least sixty per centum of whose capital is owned by such citizens, or such h igher percentage as Congress may prescribe, certain areas of investments. Issue: Whether or not the GSIS violated Section 10, second paragraph, Arti cle 11 of the 1987 Constitution Held: A constitution is a system of fundamental laws for the governance and administra tion of a nation. It is supreme, imperious, absolute and unalterable except by the authority from which it emanates. It has been defined as the fundamental an d paramount law of the nation. It prescribes the permanent framework of a system

of government, assigns to the different Held: (CONT) departments their respective powers and duties, and establishes certain fixed pr inciples on which government is founded. The fundamental conception in other wo rds is that it is a supreme law to which all other laws must conform and in acco rdance with which all private rights must be determined and all public authority administered. Under the doctrine of constitutional supremacy, Held: (CONT) Unless it is expressly provided that a legislative act is necessary to enforce a constitutional mandate, the presumption now is that all provisions of the const itution are self-executing. If the constitutional provisions are treated as req uiring legislation instead of self-executing, the legislature would have the pow er to ignore and practically nullify the mandate of the fundamental law. There may indeed be some legitimacy to the characterization that the present con troversy subject of the instant petitions - whether the filing of the second imp eachment complaint against Chief Justice Hilario G. Davide, Jr. with the House o f Representatives falls within the one year bar provided in the Constitution, an d whether the resolution thereof is a political question - has resulted in a pol itical crisis. Kilosbayan, Incorporated v. Morato Issue: whether the petitioner has the requisite personality to question the validity of the contract in this case Held: Yes. Kilosbayans status as a peoples organization give it the requisite personality to question the validity of the contract in this case. The Constitution provides that the State shall respect the role of independent peoples organizations to enable the people to pur sue and protect, within the democratic framework, their legitimate and collective interests and aspirations through peaceful and lawful means, that their right to effective and reasonable participation at all leve ls of social, political, and economic decision-making shall not be abr idged. Kilosbayan, Incorporated v. Morato These provisions have not changed the traditional rule that only real parties in interest or those with standing, as the case may be, may invoke the judicial power. The jurisdiction of the Court, even in c ases involving constitutional questions, is limited by the case and con troversy requirement of Art. VIII, 5. This requirement lies at the very heart of the judicial function. It is what differentiates decision-ma king in the courts from decision-making Kilosbayan, Incorporated v. Morato in the political departments of the government and bars the bringing of suits by just any party. It is nevertheless insisted that this Court has in the past accorded standing to taxpayers and concerned citizens in cases i nvolving paramount public interest. Taxpayers, voters, concerned citizens an d legislators have indeed been allowed to sue but then only (1) in cases involving constitutional issues and (2) under certain conditions. Petitioners do not meet these requirements on standing. Kilosbayan, Incorporated v. Morato

Taxpayers are allowed to sue, for example, where there is a claim of illegal disbursement of public funds. or where a tax measure is ass ailed as unconstitutional. Voters are allowed to question the validity of election laws because of their obvious interest in the validity o f such laws. Concerned citizens can bring suits if the constitutional question they raise is of transcendental importance which must be settle d early. Legislators are allowed to sue to question the validity of a ny official action which they claim infringes their prerogatives qua l egislators. Kilosbayan, Incorporated v. Morato Petitioners do not have the same kind of interest that these various litigants have. Petitioners assert an interest as taxpayers, but they do not meet the standing requirement for bringing taxpayers suits as set forth in Dumlao v.Comelec, to wit: While, concededly, the elections to be held involve the expenditure of public moneys, nowhere in their Petition do said petitioners allege that their tax money is being extracted and spent in violation of spe cific constitutional protections against abuses of legislative power or

Kilosbayan, Incorporated v. Morato that there is a misapplication of such funds by respondent COMELEC o r that public money is being deflected to any improper purpose. Neith er do petitioners seek to restrain respondent from wasting public fund s through the enforcement of an invalid or unconstitutional law. Besid es, the institution of a taxpayers suit, per se, is no assurance of judicial review. The Court is vested with discretion as to whether or not a taxpayers suit should be entertained. Petitioners suit does not fall under any of these categories of taxpay ers suits. or

Kilosbayan, Incorporated v. Morato Thus, petitioners right to sue as taxpayers cannot be sustained. Nor a s concerned citizens can they bring this suit because no specific inj ury suffered by them is alleged. As for the petitioners, who are mem bers of Congress, their right to sue as legislators cannot be invoked because they do not complain of any infringement of their rights as legislators.

TECSON V COMELEC 7. To what citizenship principle does the Philippines adhere to? Explain, and give illustrative case.

Held: The Philippine law on citizenship adheres to the principle of jus sanguin is. Thereunder, a child follows the nationality or citizenship of the parents r egardless of the place of his/her birth, as opposed to the doctrine of jus soli which determines nationality or citizenship on the basis of place of birth. Supremacy LAMIBINO ET AL V COMELEC

was provided by art 17 of the constitution. Their petition changes the 1987 cons titution by modifying sections 1-7 of Art 6 and sections 1-4 of Art 7 and by add ing Art 18. the proposed changes will shift the present bicameral- presidential form of government to unicameral- parliamentary. COMELEC denied the petition Supremacy LAMBINO ET AL V COMELEC

due to lack of enabling law governing initiative petitions and invoked the Sant iago Vs. Comelec ruling that RA 6735 is inadequate to implement the initiative p etitions. Issues: (1) Whether or Not the Lambino Groups initiative petition complies with S ection 2, Article XVII Supremacy LAMIBINO ET AL V COMELEC

of the Constitution on amendments to the Constitution through a peoples initiativ e; (2) Whether or Not this Court should revisit its ruling in Santiago declaring RA 6735 incomplete, inadequate or wanting in essential terms and conditions to im plement the initiative clause on proposals to Supremacy LAMIBINO ET AL V COMELEC

amend the Constitution; (3) Whether or Not the COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion in denying due course to the Lambino Groups petition. Held: According to the SC the Lambino group failed to comply with the basic requ irements for conducting a peoples initiative. T

Supremacy LAMIBINO ET AL V COMELEC

he Court held that the COMELEC did not grave abuse of discretion on dismissing t he Lambino petition. 1. The Initiative Petition Does Not Comply with Section 2, Article XVII of the C onstitution on Direct Proposal by the People Supremacy LAMIBINO ET AL V COMELEC

The petitioners failed to show the court that the initiative signer must be info rmed at the time of the signing of the nature and effect, failure to do so is dec eptive and misleading which renders the initiative void. Supremacy LAMIBINO ET AL V COMELEC

2. The Initiative Violates Section 2, Article XVII of the Constitution Disallowi ng Revision through Initiatives The framers of the constitution intended a clear distinction between amendment and

revision, it is intended that the third mode of stated in sec 2 art 17 of the co nstitution may Supremacy LAMIBINO ET AL V COMELEC

propose only amendments to the constitution. Merging of the legislative and the executive is a radical change, therefore a constitutes a revision. 3. A Revisit of Santiago v. COMELEC is Not Necessary Even assuming that RA 6735 is valid, it will not change t

Supremacy OPOSA V FACTORAN

Oposa vs. Factoran Fact: a cause of action to "prevent the misappropriation or impairment" of Philippin e rainforests and "arrest the unabated hemorrhage of the country's vital life su pport systems and continued rape of Mother Earth." Supremacy oposa v factoran

The complaint2 was instituted as a taxpayers' class suit 3 and alleges that the plaintiffs "are all citizens of the Republic of the Philippines, taxpayers, and entitled to the full benefit, use and enjoyment of the natural resource treasure that is the country's virgin tropical forests." The same was filed for themselv es and others who are equally concerned about the preservation of said resource but are "so numerous that it is impracticable to bring them all Supremacy oposa v factoran

before the Court." The minors further asseverate that they "represent their gene ration as well as generations yet unborn." 4Consequently, it is prayed for that judgment be rendered: 1] Cancel all existing timber license agreements in the country; 2] Cease and desist from receiving, accepting, processing, renewing or approving new timber license agreements. Plaintiffs further assert that the adverse and detrimental Supremacy oposa v factoran

consequences of continued and deforestation are so capable of unquestionable dem onstration that the same may be submitted as a matter of judicial notice. Issue: Whether or not petitioners have a cause of action? HELD: YES Petitioners have a cause of action. The case at bar is of common interest t o all Filipinos. The right to a balanced and healthy ecology carries with it the correlative duty to Supremacy oposa v factoran

refrain from impairing the environment. The said right implies the judicious ma nagement of the countrys forests. This right is also the mandate of the governmen t through DENR. A denial or violation of that right by the other who has the cor relative duty or obligation to respect or protect the same gives rise to a cause of action. All licenses may thus be revoked or rescinded by executive action. T he right to a balanced and healthful ecology carries with it the correlative dut y. Supremacy MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS

MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS Petitioner: Manila Prince Hotel Respondent: Government Service Insurance System (GSIS), Manila Hotel Corporation , Committee on Privatization and Office of the Government Corporate Counsel Facts: - The shares (31% to 50%) of Manila Hotel Corporation were sold by GSIS through public bidding. Supremacy MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS

- There were two bidders Manila Prince Hotel Corporation (Filipino firm) and Ren ong Berhad (Malaysian firm) - Renong Berhad bade higher than Manila Prince Hotel Supremacy MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS

Corporation. - Pending the declaration of Renong Berhad as the highest bidder, MPHC sent a ma nagers check amounting to the same bid by RB. - GSIS refused to accept offer. - Petitioner prayed for writ of mandamus and prohibition. Lower court issued a r estraining order preventing GSIS and Renong Berhad from consummating the sale. - Invoked by petitioners: Section 10 of Article XII. T Supremacy MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS

he Congress shall, upon recommendation of the economic and planning agency, when the national interest dictates, reserve to citizens of the Philippines or to co rporations or associations at least sixty per centum of whose capital is owned b y such citizens, or such higher percentage as Congress may prescribe, certain ar eas of investments. The Congress shall enact measures that will encourage the fo rmation and operation of enterprises whose capital Supremacy MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS

is wholly owned by Filipinos. (Thus, any transaction involving 51% of the shares of stock of the MHC is clearly covered by the term national economy, to which S ec. 10, second par., Art. XII, 1987 Constitution, applies.) - The answer of the respondents are the following: 1. Section 10 of Article 12 is not self-executing. For the said provision to ope rate, there must be existing laws to lay down conditions under which business may be done. 2. Granting the provision is self-executing, the Manila Hotel Corporation is not part of national patrimony. The mandate of the Constitution is addressed to the State, not to respondent GSIS which possesses a personality of its own separate and distinct from the Philippines as a State. 3. The Constitutional provision cannot be invoked because what is sold is only 5 1% of the total shares of the corporation, not the building or the land where it is built. 4. Submission by petitioner of a matching bid is

MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS premature since Renong Berhad could still very well be awarded the block of shar es and the condition giving rise to the exercise of the privilege to submit a ma tching bid had not yet taken place. 5. Submission by petitioner of a matching bid is premature since Renong Berhad c ould still very well be awarded the block of shares and the condition giving ris e to the exercise of the privilege to submit a matching bid had not yet taken pl ace. MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS premature since Renong Berhad could still very well be awarded the block of shar es and the condition giving rise to the exercise of the privilege to submit a ma tching bid had not yet taken place. 5. Submission by petitioner of a matching bid is premature since Renong Berhad c ould still very well be awarded the block of shares and the condition giving ris e to the exercise of the privilege to submit a matching bid had not yet taken pl ace. MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS

KILOSBAYAN vs. MANUEL L. MORATO G.R. No. 118910. November 16, 1995. FACTS: In Jan. 25, 1995, PCSO and PGMC signed an Equipment Lease Agreement (ELA) wherei n PGMC leased online lottery equipment and accessories to PCSO. (Rental of 4.3% of the gross amount of ticket or at least P35,000 per termina annually). 30% of the net receipts is allotted to charity. Term of lease is for 8 years. PCSO is to employ its own personnel and responsible for the facilities. Upon the expiration of lease, PCSO may purchase the equipment for P25 million. Feb. 21, 1995. A petition was filed to declare ELA invalid because it is the sam e as the Contract of Lease Petitioner's Contention: ELA was same to the Contract of Lease.. It is still violative of PCSO's charter. It is violative of the law regarding public bidding. It violates Sec. 2(2) of Art. 9-D of the 1987 Constitu tion. Standing can no longer be questioned because it has become the law of the case Respondent's reply: ELA is different from the Contract of Lease. There is n o bidding required. The power to determine if ELA is advantageous is vested in t he Board of Directors of PCSO. PCSO does not have funds. Petitioners seek to fur ther their moral crusade. Petitioners do not have a legal standing because they were not parties to the contract ISSUES: Whether or not the petitioners have standing? HELD: NO. STARE DECISIS cannot apply. The previous ruling sustaining the standing of t he petitioners is a departure from the settled rulings on real parties in intere st because no constitutional issues were actually involved. LAW OF THE CASE can not also apply. Since the present case is not the same one litigated by theparti es before in Kilosbayan vs. Guingona, Jr., the ruling cannot be in any sense be regarded as the law of this case. The parties are the same but the cases are not . PACU vs SECRETARY OF EDUCATION The petitioning colleges and universities request that Act be declared unconstitutional, because: A. They deprive owners of schools and col leges as well as teachers parents of liberty and property without due process of law; B. They deprive par ents of their natural rights and duty to rear their children for civic efficienc y; and PACU vs SECRETARY OF EDUCATION C. Their provisions conferring on the Secretary of Education unlimited power and discretion to prescribe rules and standards constitute an unlawful delegation o f legislative # It should be understandable, then, that this Court should be doubly reluctant to consider petitioners demand for avoidance of the law aforesaid, specially where, as respondents assert, petitioners suffered no wrongnor allege anyfrom the enforc ement PACU vs SECRETARY OF EDUCATION 2706 An Act making the inspection and recognition of private schools It is an established principle that to entitle a private individual immediately in danger of sustaining a direct injury as the result of that action and it is n

ot sufficient that he has merely a general to invoke the judicial power to determine the validity of executive or legislative action he m ust show that he has sustained or is interest common to all members of the publi c. PACU vs SECRETARY OF EDUCATION Bona fide suit.Judicial power is limited to the decision of actual cases and cont roversies. a hypothetical threat being insufficient In this connection, and to support their position that the law and the Secretary of Education have transcended the governmental power of supervision and regulat ion, the petitioners appended a list of circulars and memoranda issued by the sa id Department. However they failed to PACU vs SECRETARY OF EDUCATION indicate which of such official documents was constitutionally objectionable for being capricious, or pain nuisance; and it is one of our decisional practices that unless a constitutional point is specifically raised, insisted upon and adequate ly argued, the court will not consider it. (Santiago v Far Eastern We are told that such list will give an idea of how the statute has placed in th e hands of the Secretary of Education complete control of the various activities of private schools, and why the statute should be struck down as unconstitution al. KILOSBAYAN V GUINGONA Facts: This is a special civil action for prohibition and injunction, w ith a prayer for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction, which seeks to prohibit and restrain the implementation of the Contract of Lease execut ed by the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO) and the Philippine Gaming Management Corporation (PGMC) in connection with the on- line lottery system, a lso known as lotto. Petitioner Kilosbayan, Incorporated (KILOSBAYAN) avers that it is a non-stock do mestic corporation composed of civic-spirited citizens, pastors, priests, nuns, and lay leaders who are committed to the cause of truth, justice, and national r enewal. The rest of the petitioners, except Senators Freddie Webb and Wigberto T aada and Representative Joker P. Arroyo, are suing in their capacities as members of the Board of Trustees of KILOSBAYAN and as taxpayers and concerned citizens. Senators Webb and Taada and Representative Arroyo are suing in their capacities as members of Congress and as taxpayers and concerned citizens of the Philippine s. Issue: whether petitioners have legal standing to bring the suit Held: Yes. A partys standing before the Court is a procedural technical ity which it may, in the exercise of its discretion, set aside in view of the im portance of the issues raised. KILOSBAYAN V GUINGONA This technicality may be brushed aside if the transcendental importance to the p

ublic of the case demands that it be settled promptly and definitely, brushing a side, if the Court must, technicalities of procedure. KILOSBAYAN V GUINGONA This technicality may be brushed aside if the transcendental importance to the p ublic of the case demands that it be settled promptly and definitely, brushing a side, if the Court must, technicalities of procedure. Ordinary taxpayers, members of Congress, and even association of planters, and non-profit civic organizations are allowed to initiate and prosecute actions bef ore the Court to question the constitutionality or validity of laws, acts, decis ions, KILOSBAYAN V GUINGONA The instant petition is of transcendental importance to the publ ic. The issues it raised are of paramount public interest and of a category even higher than those involved in many of the aforecited cases. The ramifications of such issues imme asurably affect the social, economic, and moral well-being of the people even in the remotest barangays of the country and the counter-productive and KILOSBAYAN V GUINGONA retrogressive effects of the envisioned on-line lottery system are as staggering as the billions in pesos it is expected to raise. The legal standing then of th e petitioners deserves recognition and, in the exercise of its sound discretion, the Court hereby brushes aside the procedural barrier which the respondents tried to take advantage of. KILOSBAYAN V GUINGONA DUE PROCESS AND DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL PROTECTION

Ermita Malate v City of Manila 20 SCRA 849 (1967) Facts: Ermita-Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Association, and one of its members Hote l del Mar Inc. petitioned for the prohibition of Ordinance 4670 on June 14, 1963 to be applicable in the city of Manila. They claimed that the ordinance was beyond the powers of the Manila City Board t o regulate due to the fact that hotels were not part of its regulatory powers. T hey also asserted that Section 1 of the challenged ordinance Ermita Malate v City of Manila 20 SCRA 849 (1967) and void for being unreasonable and violative of due process insofar because it would impose P6,000.00 license fee per annum for first class motels and P4,500.0 0 for second class motels; there was also the requirement that the guests would fill up a form specifying their personal information. There was also a provision that the premises and facilities of such hotels, mote ls and lodging houses would be open for inspection from city authorites. They cl aimed this to be violative of due process Ermita Malate v City of Manila 20 SCRA 849 (1967)

and void for being unreasonable and violative of due process insofar because it would impose P6,000.00 license fee per annum for first class motels and P4,500.0 0 for second class motels; there was also the requirement that the guests would fill up a form specifying their personal information. There was also a provision that the premises and facilities of such hotels, mote ls and lodging houses would be open for inspection from city authorites. They cl aimed this to be violative of due process Ermita Malate v City of Manila 20 SCRA 849 (1967) Issue: Whether Ordinance No. 4760 of the City of Manila is violative of the due process clause? Held: No. Judgment reversed. Ratio: "The presumption is towards the validity of a law. However, the Judiciary should not lightly set aside legislative action when there is not a cl ear invasion of personal or property rights under the guise of police regulation Ermita Malate v City of Manila 20 SCRA 849 (1967) Standing or locus standi is the ability of a party to demonstrate to the court s ufficient connection to and harm from the law or action challenged to support th at party's participation in the case. More importantly, the doctrine of standing is built on the principle of separation of powers Sparing as it does unnecessary interference or invalidation by the judicial branch of the actions rendered by its co-equal branches of government.

TANADA V TUVERA II. Legal Standing Legal Standing, or locus standi, is the right of appearance in a court of justice on a given question.[21] It satisfies an important requirement before a question involving the constitutionality or legality of a law or other UP study government act may be heard and decided by a court: that it must be raised by t he proper party.[22] Stated otherwise, a court will exercise its power of judici al reviewwhich is the power of courts to determine the constitutionality or legal ity of contested executive and legislative acts[23] only if the case is brought be fore it by a party who has the legal standing to raise the constitutional or leg al question.[24] The traditional rule is that only real parties in interest or those with standing , as the case may be, may invoke the judicial power. TANADA V TUVERA Tanada v Tuvera Real parties in interest are the proper parties in cases that do not also invok e the power of judicial review. In cases that invoke the power of judicial revie w, the proper parties are those with standing. In Morato, even though the power of judicial review was invoked, Court ruled that because no constitutional question was actually involved, the i ssue was not whether petitioners had legal standing but whether they were the re al parties in interest. Tanada v Tuvera(u On this premise the Court declared that the petitioners were not the proper par ties because [i]n actions for the annulment of contractsthe real parties are those

who are parties to the agreement or are bound either principally or subsidiarily or are prejudiced in their rights with respec t to one of the contracting parties and can show the detriment which would posit ively result to them from the contractor who claim a right to take part in a publ ic bidding but have been illegally excluded from it.[27] This ruling in Morato, however, is sandwiched between prior and subsequent Supreme Court decisions which directly c ontradict it.[28] In fact, the argument that actions for annulment of government contracts may be instituted only by those bound by it was rejected as early as 1972 in City Council of Cebu City v. Cuizon,[29]in which legal standing was gran ted to city councilors who assailed a Tanada v Tuvera government contract even though no constitutional question was involved. Fairly recently in 2005, Cuizon was cited in Jumamil v. Caf,[30]also a case where no con stitutional question was involved, in ruling that [a] taxpayer need not be a part y to the contract to challenge its validity. Also, citizens standing (which was asserted in Morato) is granted in public suits because in those cases the people are regarded as the real party in interest.[32] Thus, even if no constitutional question is involved, any person with legal sta ndingalthough not Tanada v Tuvera a real party in interestmay invoke the power of judicial review. Tanada v Tuvera LAMBINO VS. COMELEC [G.R. No. 174153; 25 Oct 2006] Monday, January 19, 2009 Posted by Coffeeholic Writes Labels: Case Digests, Political Law Facts: Petitioners (Lambino group) commenced gathering signatures for an initiat ive petition to change the 1987 constitution, they filed apetition with the COME LEC to hold a plebiscite that will ratify their initiative petition under RA 673 5. Lambino group alleged that thepetition had the support of 6M individuals fulf illing what was provided by art 17 of the constitution. Their petition changes t he 1987 constitution by modifying sections 1-7 of Art 6 and sections 1-4 of Art 7 and by adding Art 18. the proposed changes will shift the presentbicameral- pr esidential form of government to unicameral- parliamentary. COMELEC denied the p etition due to lack of enabling law governing initiative petitions and invoked t he Santiago Vs. Comelec ruling that RA 6735 is inadequate to implement the initi ative petitions. Issues: (1) Whether or Not the Lambino Groups initiative petitioncomplies with Se ction 2, Article XVII of the Constitution on amendments to the Constitution thro ugh a peoples initiative; (2)Whether or Not this Court should revisit its ruling in Santiagodeclaring RA 6735 incomplete, inadequate or wanting in essential terms and conditions to implement the initiative clause on proposals to amend the Cons titution; (3) Whether or Not the COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion in denying due course to the Lambino Groups petition. Held: According to the SC the Lambino group failed to comply with the basic requ irements for conducting a peoples initiative. The Court held that the COMELEC did not grave abuse of discretion on dismissing the Lambino petition. 1. The Initiative Petition Does Not Comply with Section 2, Article XVII of the C onstitution on Direct Proposal by the People The petitioners failed to show the court that the initiative signer must be info rmed at the time of the signing of the nature and effect, failure to do so is dec

eptive and misleading which renders the initiative void. 2. The Initiative Violates Section 2, Article XVII of the Constitution Disallowi ng Revision through Initiatives

The framers of revision, it nstitution may lative and the .

the constitution intended a clear distinction between amendment and is intended that the third mode of stated in sec 2 art 17 of the co propose only amendments to the constitution. Merging of the legis executive is a radical change, therefore a constitutes a revision

3. A Revisit of Santiago v. COMELEC is Not Necessary Even assuming that RA 6735 is valid, it will not change the result because the p resent petition violated Sec 2 Art 17 to be a valid initiative, must first compl y with the constitution before complying with RA 6735 BACKGROUND Raul Lambino of Sigaw ng Bayan and Erico Aumentado of the Union of Local Authori ties of the Philippines (ULAP) filed a petition for people's initiative before t he Commission on Elections on August 25, 2006, after months of gathering signatu res all over the country. Lambino claimed that the petition is backed by 6.3 mil lion registered voters. The COMELEC denied the petition, reasoning that a lack of an enabling law keeps them from entertaining such petitions. It invoked a 1997 Supreme Court ruling (S antiago vs. COMELEC), where the Supreme Court declared RA 6735 inadequate to imp lement the initiative clause on proposals to amend the Constitution. COMELEC's ruling prompted Lambino and Aumentado to bring their case before the S upreme Court. However, the Supreme Court upheld COMELEC's ruling on the petition for people's initiative. The decision came out on October 25, 2006, with a close 8-7 vote. SUMMARY OF THE SUPREME COURT DECISION The Lambino Group miserably failed to comply with the basic requirements of the Constitution for conducting a peoples initiative. The Constitution requires that the amendment must be "directly proposed by the p eople through initiative upon a petition." Lambino's group failed to include the full text of the proposed changes in the s ignature sheets-- a fatal omission, according to the Supreme Court ruling, becau se it means a majority of the 6.3 million people who signed the signature sheets could not have known the nature and effect of the proposed changes. A peoples initiative to change the Constitution applies only to an amendment of t he Constitution and not to its revision. Only Congress or a constitutional conve ntion may propose revisions to the Constitution. A peoples initiative may propose only amendments to the Constitution. "A popular clamor, even one backed by 6.3 million signatures, cannot justify a d eviation from the specific modes prescribed in the Constitution itself." -- Supr eme Court The Supreme Court sees no need to revisit an earlier ruling since the present ca se (Lambino vs. COMELEC) can be resolved on some other grounds. In a 1997 ruling on Santiago vs. COMELEC, the Supreme Court ruled that RA 6735 ( the law regulating the people's right of initiative) was inadequate to cover the system of initiative on constitutional amendments. In the present case, the Lambino group failed to comply with the basic requireme nts of the Constitution on conducting a people's initiative. That alone warrants the petition's dismissal. An affirmation or reversal of Santiago will not change the its outcome of the pr

esent petition. The COMELEC did not commit grave abuse of discretion in dismissing the Lambino G roup's petition for people's initiative. COMELEC merely followed the Supreme Court's earlier ruling on Santiago vs. COMEL EC LAMBINO VS. COMELEC (PEOPLE'S INITIATIVE) Lambino, et al. vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 174153, 25 October 2006) Digest On 15 February 2006, the group of Raul Lambino and Erico Aumentado (Lambino Group) commenced gathering signatures for an initiative petition to change the1987 Con stitution. On 25 August 2006, the Lambino Group filed a petition with the Commis sion on Elections (COMELEC) to hold a plebiscite that will ratify their initiati ve petition under Section 5(b) and (c) and Section 7 of Republic Act No. 6735 or the Initiative and Referendum Act. The proposed changes under the petition will shift the present Bicameral-Presidential system to a Unicameral-Parliamentary f orm of government. The Lambino Group claims that: (a) their petition had the support of 6,327,952 i ndividuals constituting at least 12% of all registered voters, with each legisla tive district represented by at least 3% of its registered voters; and (b) COMEL EC election registrars had verified the signatures of the 6.3 million individual s. The COMELEC, however, denied due course to the petition for lack of an enabling law governing initiative petitions to amend the Constitution, pursuant to the Su preme Courts ruling in Santiago vs. Commission on Elections. The Lambino Group elev ated the matter to the Supreme Court, which also threw out the petition. 1. The initiative petition does not comply with Section 2, Article XVII of the C onstitution on direct proposal by the people Section 2, Article XVII of the Constitution is the governing provision that allo ws a peoples initiative to propose amendments to the Constitution. While this provi sion does not expressly state that the petition must set forth the full text of the proposed amendments, the deliberations of the framers of our Constitution cl early show that: (a) the framers intended to adopt the relevant American jurispr udence on peoples initiative; and (b) in particular, the people must first see t he full text of the proposed amendments before they sign, and that the people mu st sign on a petition containing such full text. The essence of amendments directly proposed by the people through initiative upon a petition is that the entire proposal on its face is a petition by the people. This means two essential elements must be present. First, the people must author and thus sign the entire proposal. No agent or rep resentative can sign on their behalf. Second, as an initiative upon a petition, the proposal must be embodied in a pet ition. These essential elements are present only if the full text of the proposed amend ments is first shown to the people who express their assent by signing such comp lete proposal in a petition. The full text of the proposed amendments may be eit her written on the face of the petition, or attached to it. If so attached, the petition must state the fact of such attachment. This is an assurance that every one of the several millions of signatories to the petition had seen the full te xt of the proposed amendments before not after signing. Moreover, an initiative signer must be informed at the time of signing of the nat ure and effect of that which is proposed and failure to do so is deceptive and mis leading which renders the initiative void. In the case of the Lambino Groups petition, theres not a single word , phrase, or sentence of text of the proposed changes in the signature sheet. Ne ither does the signature sheet state that the text of the proposed changes is at tached to it. The signature sheet merely asks a question whether the people appr ove a shift from the Bicameral-Presidential to the Unicameral- Parliamentary sys tem of government. The signature sheet does not show to the people the draft of the proposed changes before they are asked to sign the signature sheet. This omi

ssion is fatal. An initiative that gathers signatures from the people without first showing to t he people the full text of the proposed amendments is most likely a deception, a nd can operate as a gigantic fraud on the people. Thats why the Constitution requ ires that an initiative must be directly proposed by the people x x x in a petiti on meaning that the people must sign on a petition that contains the full text of the proposed amendments. On so vital an issue as amending the nations fundamenta l law, the writing of the text of the proposed amendments cannot be hidden from the people under a general or special power of attorney to unnamed, faceless, an d unelected individuals. 2. The initiative violates Section 2, Article XVII of the Constitution disallowi ng revision through initiatives Article XVII of the Constitution speaks of three modes of amending the Constitut ion. The first mode is through Congress upon three-fourths vote of all its Membe rs. The second mode is through a constitutional convention. The third mode is th rough a peoples initiative. Section 1 of Article XVII, referring to the first and second modes, applies to an y amendment to, or revision of, this Constitution. In contrast, Section 2 of Arti cle XVII, referring to the third mode, applies only to amendments to this Constit ution. This distinction was intentional as shown by the deliberations of the Cons titutional Commission. A peoples initiative to change the Constitution applies on ly to an amendment of the Constitution and not to its revision. In contrast, Con gress or a constitutional convention can propose both amendments and revisions t o the Constitution. Does the Lambino Groups initiative constitute an amendment or revision of the Con stitution? Yes. By any legal test and under any jurisdiction, a shift from a Bic ameral-Presidential to a Unicameral-Parliamentary system, involving the abolitio n of the Office of the President and the abolition of one chamber of Congress, i s beyond doubt a revision, not a mere amendment. Courts have long recognized the distinction between an amendment and a revision of a constitution. Revision broadly implies a change that alters a basic princip le in the constitution, like altering the principle of separation of powers or t he system of checks-and-balances. There is also revision if the change alters th e substantial entirety of the constitution, as when the change affects substanti al provisions of the constitution. On the other hand, amendment broadly refers t o a change that adds, reduces, or deletes without altering the basic principle i nvolved. Revision generally affects several provisions of the constitution, whil e amendment generally affects only the specific provision being amended. Where the proposed change applies only to a specific provision of the Constituti on without affecting any other section or article, the change may generally be c onsidered an amendment and not a revision. For example, a change reducing the vo ting age from 18 years to 15 years is an amendment and not a revision. Similarly , a change reducing Filipino ownership of mass media companies from 100% to 60% is an amendment and not a revision. Also, a change requiring a college degree as an additional qualification for election to the Presidency is an amendment and not a revision. The changes in these examples do not entail any modification of sections or arti cles of the Constitution other than the specific provision being amended. These changes do not also affect the structure of government or t he system of checks-and-balances among or within the three branches. However, there can be no fixed rule on whether a change is an amendment or a rev ision. A change in a single word of one sentence of the Constitution may be a re vision and not an amendment. For example, the substitution of the word republican with monarchic or theocratic in Section 1, Article II of the Constitution radically overhauls the entire structure of government and the fundamental ideological bas is of the Constitution. Thus, each specific change will have to be examined case -by-case, depending on how it affects other provisions, as well as how it affect s the structure of government, the carefully crafted system of checks-and-balanc es, and the underlying ideological basis of the existing Constitution. Since a revision of a constitution affects basic principles, or several provisio

ns of a constitution, a deliberative body with recorded proceedings is best suit ed to undertake a revision. A revision requires harmonizing not only several pro visions, but also the altered principles with those that remain unaltered. Thus, constitutions normally authorize deliberative bodies like constituent assemblie s or constitutional conventions to undertake revisions. On the other hand, const itutions allow peoples initiatives, which do not have fixed and identifiable deli berative bodies or recorded proceedings, to undertake only amendments and not re visions. In California where the initiative clause allows amendments but not revisions to the constitution just like in our Constitution, courts have developed a two-par t test: the quantitative test and the qualitative test. The quantitative test as ks whether the proposed change is so extensive in its provisions as to change di rectly the substantial entirety of the constitution by the deletion or alteratio n of numerous existing provisions. The court examines only the number of provisi ons affected and does not consider the degree of the change. The qualitative test inquires into the qualitative effects of the proposed chang e in the constitution. The main inquiry is whether the change will accomplish such far reaching changes in the nature of our basic governmental plan as to amount t o a revision. Whether there is an alteration in the structure of government is a p roper subject of inquiry. Thus, a change in the nature of [the] basic governmental plan includes change in its fundamental framework or the fundamental powers of its Branches. A change in the nature of the basic governmental plan also includes c hanges that jeopardize the traditional form of government and the system of chec k and balances. Under both the quantitative and qualitative tests, the Lambino Group initiative is a revision and not merely an amendment. Quantitatively, the Lambino Group pro posed changes overhaul two articles Article VI on the Legislature and Article VI I on the Executive affecting a total of 105 provisions in the entire Constitutio n. Qualitatively, the proposed changes alter substantially the basic plan of gov ernment, from presidential to parliamentary, and from a bicameral to a unicamera l legislature. A change in the structure of government is a revision of the Constitution, as wh en the three great co-equal branches of government in the present Constitution a re reduced into two. This alters the separation of powers in the Constitution. A shift from the present Bicameral-Presidential system to a Unicameral-Parliament ary system is a revision of the Constitution. Merging the legislative and executive branches is a radical change in the structure of government. The abolition alon e of the Office of the President as the locus of Executive Power alters the sepa ration of powers and thus constitutes a revision of the Constitution. Likewise, the abolition alone of one chamber of Congress alters the system of checks-and-b alances within the legislature and constitutes a revision of the Constitution. The Lambino Group theorizes that the difference between amendment and revision is o of procedure, not of substance. The Lambino Group posits that when a deliberati ve body drafts and proposes changes to the Constitution, substantive changes are called revisions because members of the deliberative body work full-time on the chan ges. The same substantive changes, when proposed through an initiative, are call ed amendments because the changes are made by ordinary people who do not make an occu ion, profession, or vocation out of such endeavor. The SC, however, ruled that the express intent of the framers and the plain language of the Constitution contra dict the Lambino Groups theory. Where the intent of the framers and the language of the Constitution are clear and plainly stated, courts do not deviate from such categorical intent and language. 3. A revisit of Santiago vs. COMELEC is not necessary The petition failed to comply with the basic requirements of Section 2, Article XVII of the Constitution on the conduct and scope of a peoples initiative to ame nd the Constitution. There is, therefore, no need to revisit this Courts ruling in Santiago declaring RA 6735 incomplete, inadequate or wanting in essential ter ms and conditions to cover the system of initiative to amend the Constitution. A n affirmation or reversal of Santiago will not change the outcome of the present

petition. It settled that courts will not pass upon the constitutionality of a statute if the case can be resolved on some other grounds. Even assuming that RA 6735 is valid, this will not change the result here becaus e the present petition violates Section 2, Article XVII of the Constitution, whi ch provision must first be complied with even before complying with RA 6735. Wor se, the petition violates the following provisions of RA 6735: a. Section 5(b), requiring that the people must sign the petition as signatories . The 6.3 million signatories did not sign the petition or the amended petition filed with the COMELEC. Only Attys. Lambino, Donato and Agra signed the petition and amended petition. b. Section 10(a), providing that no petition embracing more than one subject sha ll be submitted to the electorate. The proposed Section 4(4) of the Transitory P rovisions, mandating the interim Parliament to propose further amendments or rev isions to the Constitution, is a subject matter totally unrelated to the shift i n the form of government

ARSENIO LUMIQUED VS APOLONIO EXEVEA ARSENIO P. LUMIQUED (deceased), Regional Director, DAR CAR, Represented by his H eirs, Francisca A. Lumiqued, May A. Lumiqued, Arlene A. Lumiqued and Richard A. Lumiqued, petitioners, vs. Honorable APOLONIO G. EXEVEA, ERDOLFO V. BALAJADIA and FELIX T. CABADING, ALL Me mbers of Investigating Committee, created by DOJ Order No. 145 on May 30, 1992; HON. FRANKLIN M. DRILON, SECRETARY OF JUSTICE, HON. ANTONIO T. CARPIO, CHIEF Pre sidential Legal Adviser/Counsel; and HON. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING, Senior Deputy Executive Secretary of the Office of the President, and JEANNETTE OBAR-ZAMUDIO, Private Respondent, respondents. ROMERO, J.: Does the due process clause encompass the right to be assisted by counsel during an administrative inquiry? Arsenio P. Lumiqued was the Regional Director of the Department of Agrarian Refo rm Cordillera Autonomous Region (DAR-CAR) until President Fidel V. Ramos dismiss ed him from that position pursuant to Administrative Order No. 52 dated May 12, 1993. In view of Lumiqued's death on May 19, 1994, his heirs instituted this pet ition for certiorari and mandamus, questioning such order. The dismissal was the aftermath of three complaints filed by DAR-CAR Regional Ca shier and private respondent Jeannette Obar-Zamudio with the Board of Discipline of the DAR. The first affidavit-complaint dated November 16, 1989, 1 charged Lu miqued with malversation through falsification of official documents. From May t o September 1989, Lumiqued allegedly committed at least 93 counts of falsificati on by padding gasoline receipts. He even submitted a vulcanizing shop receipt wo rth P550.00 for gasoline bought from the shop, and another receipt for P660.00 f or a single vulcanizing job. With the use of falsified receipts, Lumiqued claime d and was reimbursed the sum of P44,172.46. Private respondent added that Lumiqu ed seldom made field trips and preferred to stay in the office, making it imposs ible for him to consume the nearly 120 liters of gasoline he claimed everyday. In her second affidavit-complaint dated November 22, 1989, 2 private respondent accused Lumiqued with violation of Commission on Audit (COA) rules and regulatio ns, alleging that during the months of April, May, July, August, September and O ctober, 1989, he made unliquidated cash advances in the total amount of P116,000 .00. Lumiqued purportedly defrauded the government "by deliberately concealing h is unliquidated cash advances through the falsification of accounting entries in order not to reflect on 'Cash advances of other officials' under code 8-70-600 of accounting rules." The third affidavit-complaint dated December 15, 1989, 3 charged Lumiqued with o ppression and harassment. According to private respondent, her two previous comp

laints prompted Lumiqued to retaliate by relieving her from her post as Regional Cashier without just cause. ARSENIO LUMIQUED VS APOLONIO EXEVEA The three affidavit-complaints were referred in due course to the Department of Justice (DOJ) for appropriate action. On May 20, 1992, Acting Justice Secretary Eduardo G. Montenegro issued Department Order No. 145 creating a committee to in vestigate the complaints against Lumiqued. The order appointed Regional State Pr osecutor Apolinario Exevea as committee chairman with City Prosecutor Erdolfo Balajadia and Provincial Prosecu tor Felix Cabading as members. They were mandated to conduct an investigation wi thin thirty days from receipt of the order, and to submit their report and recom mendation within fifteen days from its conclusion. The investigating committee accordingly issued a subpoena directing Lumiqued to submit his counter-affidavit on or before June 17, 1992. L umiqued, however, filed instead an urgent motion to defer submission of his coun ter-affidavit pending actual receipt of two of private respondent's complaints. The committee granted the motion and gave him a five-day extension. In his counter-affidavit dated June 23, 1992, 4 Lumiqued alleged, inter alia, th at the cases were filed against him to extort money from innocent public servant s like him, and were initiated by private respondent in connivance with a certai n Benedict Ballug of Tarlac and a certain Benigno Aquino III. He claimed that th e apparent weakness of the charge was bolstered by private respondent's executio n of an affidavit of desistance. 5 Lumiqued admitted that his average daily gasoline consumption was 108.45 liters. He submitted, however, that such consumption was warranted as it was the aggreg ate consumption of the five service vehicles issued under his name and intended for the use of the Office of the Regional Director of the DAR. He added that the receipts which were issued beyond his region were made in the course of his tra vels to Ifugao Province, the DAR Central Office in Diliman, Quezon City, and Lag una, where he attended a seminar. Because these receipts were merely turned over to him by drivers for reimbursement, it was not his obligation but that of audi tors and accountants to determine whether they were falsified. He affixed his si gnature on the receipts only to signify that the same were validly issued by the establishments concerned in order that official transactions of the DAR-CAR cou ld be carried out. Explaining why a vulcanizing shop issued a gasoline receipt, Lumiqued said that he and his companions were cruising along Santa Fe, Nueva Vizcaya on their way t o Ifugao when their service vehicle ran out of gas. Since it was almost midnight , they sought the help of the owner of a vulcanizing shop who readily furnished them with the gasoline they needed. The vulcanizing shop issued its own receipt so that they could reimburse the cost of the gasoline. Domingo Lucero, the owner of said vulcanizing shop, corroborated this explanation in an affidavit dated J une 25, 1990. 6 With respect to the accusation that he sought reimbursement in t he amount of P660.00 for one vulcanizing job, Lumiqued submitted that the amount was actually only P6.60. Any error committed in posting the amount in the books of the Regional Office was not his personal error or accountability. To refute private respondent's allegation that he violated COA rules and regulat ions in incurring unliquidated cash advances in the amount of P116,000.00, Lumiq ued presented a certification 7 of DAR-CAR Administrative Officer Deogracias F. Almora that he had no outstanding cash advances on record as of December 31, 198 9. In disputing the charges of oppression and harassment against him, Lumiqued cont ended that private respondent was not terminated from the service but was merely relieved of her duties due to her prolonged absences. While admitting that priv ate respondent filed the required applications for leave of absence, Lumiqued cl aimed that the exigency of the service necessitated disapproval of her applicati on for leave of absence. He allegedly rejected her second application for leave of absence in view of her failure to file the same immediately with the head off ice or upon her return to work. He also asserted that no medical certificate sup

ported her application ARSENIO LUMIQUED VS APOLONIO EXEVEA for leave of absence. In the same counter-affidavit, Lumiqued also claimed that private respondent was corrupt and dishonest because a COA examination revealed that her cash accounta bilities from June 22 to November 23, 1989, were short by P30,406.87. Although p rivate respondent immediately returned the amount on January 18, 1990, the day f ollowing the completion of the cash examination, Lumiqued asserted that she shou ld be relieved from her duties and assigned to jobs that would not require handl ing of cash and money matters. Committee hearings on the complaints were conducted on July 3 and 10, 1992, but Lumiqued was not assisted by counsel. On the second hearing date, he moved for i ts resetting to July 17, 1992, to enable him to employ the services of counsel. The committee granted the motion, but neither Lumiqued nor his counsel appeared on the date he himself had chosen, so the committee deemed the case submitted fo r resolution. On August 12, 1992, Lumiqued filed an urgent motion for additional hearing, 8 al leging that he suffered a stroke on July 10, 1992. The motion was forwarded to t he Office of the State Prosecutor apparently because the investigation had already been terminated. In an order dated September 7, 19 92, 9 State Prosecutor Zoila C. Montero denied the motion, viz: The medical certificate given show(s) that respondent was discharged from the Sa cred Heart Hospital on July 17, 1992, the date of the hearing, which date was up on the request of respondent (Lumiqued). The records do not disclose that respon dent advised the Investigating committee of his confinement and inability to att end despite his discharge, either by himself or thru counsel. The records likewi se do not show that efforts were exerted to notify the Committee of respondent's condition on any reasonable date after July 17, 1992. It is herein noted that a s early as June 23, 1992, respondent was already being assisted by counsel. Moreover an evaluation of the counter-affidavit submitted reveal(s) the sufficie ncy, completeness and thoroughness of the counter-affidavit together with the do cumentary evidence annexed thereto, such that a judicious determination of the c ase based on the pleadings submitted is already possible. Moreover, considering that the complaint-affidavit was filed as far back as Nove mber 16, 1989 yet, justice can not be delayed much longer. Following the conclusion of the hearings, the investigating committee rendered a report dated July 31, 1992, 10finding Lumiqued liable for all the charges again st him. It made the following findings: After a thorough evaluation of the evidences (sic) submitted by the parties, thi s committee finds the evidence submitted by the complainant sufficient to establ ish the guilt of the respondent for Gross Dishonesty and Grave Misconduct. That most of the gasoline receipts used by the respondent in claiming for the re imbursement of his gasoline expenses were falsifi ARSENIO LUMIQUED VS APOLONIO EXEVEA ed is clearly established by the 15 Certified Xerox Copies of the duplicate rec eipts (Annexes G-1 to G-15) and the certifications issued by the different gasol ine stations where the respondent purchased gasoline. Annexes "G-1" to "G-15" sh ow that the actual average purchase made by the respondent is about 8.46 liters only at a purchase price of P50.00, in contrast to the receipts used by the resp ondent which reflects an average of 108.45 liters at a purchase price of P550.00 . Here, the greed of the respondent is made manifest by his act of claiming reim bursements of more than 10 times the value of what he actually spends. While onl y 15 of the gasoline receipts were ascertained to have been falsified, the motiv e, the pattern and the scheme employed by the respondent in defrauding the gover nment has, nevertheless, been established. That the gasoline receipts have been falsified was not rebutted by the responden t. In fact, he had in effect admitted that he had been claiming for the payment