Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Managing Performance-Related Pay

Uploaded by

Anupam NandaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Managing Performance-Related Pay

Uploaded by

Anupam NandaCopyright:

Available Formats

Managing performance-related pay based on evidence from the nancial services sector

Philip Lewis, Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education

n recent years performance management has come to the fore as organisations seek constantly to optimise their human resources in the face of growing competitive pressures. The increased interest in performance management has been mirrored by the popularity of performance-related pay (PRP) schemes which reward individual employees on the basis of their job performance, de ned as `a method of payment where an individual employee receives increases in pay based wholly or partly on the regular and systematic assessment of job performance (ACAS, 1996: 8). Indeed, definitions of performance management (eg Clark, 1995; Storey and Sisson, 1993) often include PRP as an intrinsic part of this approach. However, the PRP literature indicates that unsuccessful implementation of PRP is often associated with ineffective performance management processes (see, for example, Cannell and Wood, 1992; Marsden and Richardson, 1992). But, as Dowling and Richardson (1997) note, there have been few attempts to explain empirically any observed success or failure of PRP, including the extent to which ineffective implementation may explain PRP failure. This article seeks to shed light on this debate. It has two aims: the rst is to identify the perf orma nce managemen t processes which are fundamen tal to the successful implementation of PRP; the second, to establish how effectively these processes were conducted in three organisations which were the subject of this research. RESEARCH DESIGN The focus of the overall study was to arrive at an explanatory theory of the effectiveness of PRP schemes. The research design featured three nancial services organisations: Finbank, a high street bank, Finsoc, a major building society, and Premierco, a leading insurance company. It was anticipated that data collection in three organisations would result in a more valid explanatory theory of PRP success than if only one organisation had been used. Financial services was chosen because it is in this sector that PRP has been embraced with particular enthusiasm, due to the perceived need to generate more commercially aware behaviour among employees in an increasingly competitive product market a need with which PRP was assumed to be consistent (Snape et al, 1992). The focus of the study was on managers at branch (or equivalent) level the recipients of PRP. In the three organisations, PRP operated in a similar way for managers at this level, and this was the reason for choosing this employee category. Each organisation operated its scheme under the umbrella of a performance management system. In all three the cornerstone of this system was the setting of objectives by the implementing manager for the recipient manager; these were derived from the organisations objectives. These individual objectives were assessed at least annually and triggered a performance-based award. Assessment in each organisation was on a ve-point scale with any performance award being determined by individual performance. Each of the organisations had been running its PRP scheme since the late 1980s.

66

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2

Philip Lewis, Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education

The main method of data collection was through semi-structured interviews lasting one hour or more with 63 recipient managers, together with 23 managers who were either the implementers of the scheme (usually area managers) or the designers of the performance management scheme (personnel specialists). The semi-structured interview was chosen because of its ability to probe beneath the surface of information that otherwise may be accepted at face value or, alternatively, not disclosed. For example, in the Finbank pilot study the organisations concern to use PRP to reduce labour costs was not revealed in the rst instance in senior manager interviews. But it was apparent that this was the perception of branch managers; this was con rmed in subsequent senior management interviews. Both the general management and personnel management perspectives were thought to be important so that a full picture could be obtained. Data analysis was consistent with the grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Initially the data were disaggregated into conceptual units which were labelled according to the main themes which arose. Initial de nition of relationships between these themes was conducted and then a nal de nition of categories and sub-categories was developed. The eldwork was conducted over a period of 18 months between 1993 and 1995. In addition to interviews with managers, the author also attended managerial meetings, studied organisational documentation and had two three-hour discussions with relevant trade union of cials. PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT PROCESSES AND PRP Analysis of the data suggested there were several key activities in the implementation of PRP. What was clear was these had more to do with what have become known as performance management processes than they did with pay per se. This pointed the way to an analytical framework derived from the performance management literature. Performance management is a term used to describe an integrated set of techniques which have had an independ ent existence under their own names, eg performance appraisal. There is no clear agreed de nition of performance management. Storey and Sisson (1993) note that, at its broadest, the term can mean any activity which is designed to improve the performance of employees. At its narrowest, performance management is used to refer to individual PRP. Storey and Sisson (1993) note that performance management has three basic activities: 1. setting clear objectives for individual employees which are derived from the organisations strategy and departmental strategies; 2. formal monitoring and review of progress towards these objectives; and 3. using the outcomes of the review process to reinforce desired employee behaviour through differential rewards and identifying training and development needs. Clark (1995) stresses one important additional facet of performance management activity: that of feeding back to the employee the results of the formal monitoring. It can be seen from the above definition that PRP is usually an intrins ic part of performance management. The IPM survey on performance management (Institute of Personnel Management, 1992) reported that two-thirds of the respondent organisations which operated PRP without other performance management policies thought that PRP had contributed to improved organisational performance. This contrasted with 94 per cent of the sample which operated PRP with other performance management policies, who thought PRP had contributed to improved organisational performance. This suggests the importance

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2 67

Managing performance-related pay based on evidence from the nancial services sector

of PRP being located within the context of performance management activities, ie activities which set objectives, measure performance and give feedback against objectives. The IPM survey claims several advantages for performance management, including: l more effective employees able to meet increased product market competition; l the pushing of key decisions down the organisational structure to line managers, together with a greater acceptance of accountability by such managers; and l reward structures which reward performance. Among the bene ts of performance management claimed by Clark (1995: 186) is that it `provides a means of inspecting the functioning of the process links which deliver performance against objectives. It is this last bene t of performance management which makes it particularly attractive as a tool to analyse the implementation of PRP. In the case study organisations PRP was concerned with delivering performance against objectives and examining the process links between the various aspects of the implementation of PRP offered a thorough way of analysing the data. Storey and Sisson (1993) and Clark (1995) represent performance management as a cycle of activities. Analysis of the PRP data in this study was conducted using a cycle derived from this work. Figure 1 illustrates the PRP process cycle, shown here as an interactive cycle as opposed to a series of discrete activities; that is, the processes are presented in a logical order and there is a relationship between each of the processes in the cycle in that each one affects the others. The interactive nature of the model, indicated by the arrows, requires explanation. Clearly, the performance objectives set in stage 1 of the cycle are those which it is intended to measure in stage 2. But the arrow pointing back to stage 1 indicates that the measurement process may involve a redefinition of the objectives. Underperformance may lead to a decrease in targets and overachievement an increase. The performance measurement process will provide feedback to recipient managers on their performance level in stage 3 of the cycle. The arrow returning to stage 2 indicates that a consequence of this process may be modi cation of the measures being used and of the way in which the feedback is given, eg too infrequently or too critically. Feedback on performance eventually leads to the performance rating derived being translated into a pay award in stage 4. Here, the arrow points back to stage 1 because it is possible that recipient managers may appeal, either informally or formally, against the rating and the amount awarded. This may lead to a modi cation of the rating, award and future objectives. As Lawler (1995) asserts, communication is a key aspect of the cycle. Communication of relevant performance management information from implementing managers to PRP recipients is placed at the centre of the model and it is seen to be essential that this ows around the complete process cycle. This involves the setting objectives stage. For example, what are the origins of the objectives? What are the objectives of colleagues, of other divisions and regions? Performance measurement calls into question the extent to which information about other recipients is communicated. Communication is obviously at the heart of the feedback giving process. For example, how much justi cation is given for the assessments made? Translation of performance rating into award implies the need for communication of information about the expected level of the `pot size and the implications of this for the respective levels of rating. Knowledge of this allows the potential recipient to be clear about the award he or she can expect. Clearly, the PRP process cycle represents an idealised approach to the implementation of PRP. But it is used here principally as a `means of inspecting the functioning of the process links which deliver performance against objectives (Clark, 1995: 186) at Finbank, Finsoc and Premierco. The data are presented below in the order of each stage of the cycle.

68 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2

Philip Lewis, Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education

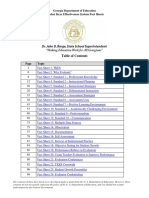

FIGURE 1 PRP process cycle Stage 1: setting objectives

Stage 2: measuring performance

COMMUNICATION

Stage 3: giving performance feedback

Stage 4: translating performance into award

Source: developed from Clark (1995) and Storey and Sisson (1993) NB Bold arrows represent forward progression throughout the cycle. The lighter arrows indicate the possibility of each stage being revisited as a consequence of what happens at that stage. See text for full explanation.

Effectiveness of PRP process cycle in the three case study organisations Stage 1: setting objectives Fundamental to performance management are measures of performance. Lawler (1990) argues that these should be credible and comprehensive; without these ingredients a successful scheme is impossible. Pre-determined objectives are one of the most popular forms of measuring performance (ACAS, 1996) and were used in each of the three case study organisations. Performance management ineffectiveness may not only be a product of inappropriate objectives but lack of management skill in their application (Lawler, 1990). In their study Cannell and Wood (1992) conclude that, while managers found the setting of objectives easy, the assessment of their impact and effectiveness was less so. These potential problems are re ected in the data from the case studies in this research, where the main weaknesses were the imposition, narrowness and number of objectives. At Finbank the way in which the objectives were set was the cause of unease. The of cial line was that objectives were negotiated by the branch manager with the area manager. Yet most branch managers insisted the reality was that they were imposed by the bank on area managers and by area managers on branch managers:

There was the opportunity last year to have some say in this but the bank just went ahead and imposed what they wanted to impose anyway. Branch manager ... branch managers complained there was no such thing as negotiation, that they [objectives] were imposed. So the employee relations manager at the time said, `OK, lets make it clear they are imposed. Union national of cer

In addition, the scope of performance objectives for Finbank managers was narrow. They seemed only to dwell on the achievement of nancial business targets. This encouraged managers to concentrate on the short term rather than build long-term developmental relationships with staff and customers.

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2 69

Managing performance-related pay based on evidence from the nancial services sector

At Finsoc the performance objectives fell into two categories business/ nancial and personal development. The latter category covered speci c areas related to the development of the branch (eg branch appearance) as well as the development of the manager. The former category consisted of hard, quantitative measures; the latter soft and qualitative. There seemed little doubt from interview evidence that the business/ nancial objectives were imposed and the personal development objectives were negotiated. According to one area manager, this was inevitable:

In reality, there is little opportunity for managers to in uence me in the targets I set for them. In the same way I cant really in uence my boss. The society hands down the goals and we have to work to them. Area manager

All Finsoc area managers interviewed pointed out that at least they were likely to give branch managers the opportunity to disagree with their objectives. But branch managers all echoed the point that, although there was the opportunity to disagree, there was little point in doing so. There was also evidence at Finsoc that managers thought there were too many objectives:

There are too many key performance areas about 20. This is far too many because managers lose sight of the ones they really should be aiming for... Area manager

This may be the reason why, as many branch managers confessed, they did not refer to the performance agreement frequently, seeing it as little more than bureaucracy. Managers at Premierco were less critical of the objective setting process. The hub of the PRP system was the performance contract. Future objectives for managers were derived from the companys strategic objectives and the previous annual appraisal round. These were written into a performance contract giving the manager explicit standards which re ected the need for improved performance. Premierco managers had a high achievement orientation: set them a target and they would strive to achieve it. Overall, there appeared to be more evidence of ineffective than effective implementation of stage 1 of the PRP process cycle. This had the effect of disenfranchising the recipient managers, of creating the impression that the PRP process cycle was something that was `done to them rather than something in which they played an active part. Stage 2: measuring performance A consistent theme in the PRP literature is that employees agree in principle with the concept but disagree with the way in which schemes are operated (see, for example, Kessler, 1994). This calls into question the processes in the performance management cycle. Two main issues dominate the empirical literature (eg Procter et al, 1993; Marsden and Richardson, 1992): the extent to which employees feel favouritism is being practised and the tendency for ratings to cluster at the mid-point in the distribution. Such clustering has the effect of not discriminating between individuals, which they feel is unfair. Finbank managers expressed concern about the subjectivity of the measurement process. Some managers were worried about the lack of congruence between their views on the variables affecting achievement and those of the rating manager. The general view seemed to be: `its okay as long as he thinks in the same way as you. A fear of a small group of corporate lending managers was that their implementing manager may not understand all the complexities of the job, thereby exacerbating the worst effects of rating subjectivity. Favouritism was an issue with some Finbank managers. This had four strands. The rst was the straightforward `if you dont get on with your manager its not so good for your PRP. The second strand was that `managers have their pet issues, and the third related to the extent to which the manager was visible in the performance of the job. But the fourth

70 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2

Philip Lewis, Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education

strand of favouritism was the most insidious the `old boy network. There were distinct social groupings in the bank, which meant promotions were often seen to be based on this rather than on performance. Many interviewees thought there was still too much of this in the bank:

After all, a lot of managers have put in a lot of service together and grown up together in the bank. This meant there tended to be great insularity. Managers are reluctant to lose people theyve groomed. Business banking manager

Perceived favouritism manifested itself in a different way at Finsoc. Branch managers felt staff in head of ce received systematically higher ratings than retail staff. This was part of a wider issue of perceived unfairness in that retail staff thought head of ce staff at Finsoc had an `easy life in comparison with them.

I... spent a year in the head of ce and I couldnt believe the lack of pressure those people there were experiencing. I think a lot of them ought to have a spell in the branches and see what life is really like. Branch manager

Managers choosing the `safe rating was a significant problem at Finsoc. This was recognised by branch and area managers and the retail HR manager; the latter thought this may have been due to the availability of so many options (nine) for the rating manager. In 1993-4, 84 per cent of Finsoc staff received ratings which used just three (mid-point) of the nine rating options. The most signi cant consequence of this was that genuine good or poor performance was not recognised or rewarded:

One of the problems with the last award was the difference between a 3 and a 3.5 rating. It translated to 0.1 per cent of the increase last time which is ridiculous. People will rightly ask, why did I bother? The difference in effort required surely warrants more than that! Branch manager

The low level of funds in the PRP `pot in recent years may explain the lack of differentiation. However, some argued that this was an example of managers `taking the easy way out and not being prepared to be accountable for their actions. For Premierco managers the measures were precise and demanding. Managers were measured on keeping within budget, meeting service quality standards, meeting nancial controls, relationships with other departments and relationships with staff. The implementing manager was not the sole arbiter of performance. Feedback was obtained from all parties who were relevant to job performance, including, importantly, immediate colleague managers and other managers able to contribute. It also involved the completion of a questionnaire by the manager s staff on her performance as a people manager. The consequence of using such a wide range was that recipient managers saw the feedback process as far more complete and the eventual PRP award much more accurate. PRP at Premierco depended upon improved performance. Managers were continually set fresh challenges in one form or another. This may not have been promotion but perhaps a new project or extra functional responsibility, thus ensuring intrinsic motivation. Few managers interviewed had been doing their jobs for more than two years. Another facet of the performance measurement stage of the PRP process cycle which was effective at Premierco was the meeting of implementing managers on a quarterly basis to review the ratings given to recipient managers. This was pursued to achieve greater conformity across the division and had the effect of ensuring that implementing managers justi ed their decisions to peers. Stage 3: giving performance feedback Feedback on performance is seen as part of the wider issue of communication in the prescriptive performance management literature (see, for example, McAdams, 1988; Hoevemeyer, 1989) and deemed to be a process of key signi cance.

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2 71

Managing performance-related pay based on evidence from the nancial services sector

There was no impression that Finbank managers were receiving qualitative feedback on their job performance. This could have been provided by the area manager or other senior managers. Indeed, there was no evidence that managers were encouraged to learn from the experiences of others. Advancement was something which was seen in terms of salary or promotion. But for many managers salary had effectively been capped and promotion opportunities had been reduced by initiatives which had seen layers of management removed. There was also evidence at Finsoc that the performance management process was not conducted thoroughly. One area manager readily admitted that he only did three reviews a year rather than the prescribed four. It was not dif cult to have some sympathy with his reasons:

There is a far too big a span of control on my part and the managers managing me. If you take my manager as an example. He has 23 direct reports and he has to do four appraisals a year thats 23 times four times 20 key performance indicators!

One of the key performance monitoring aspects was the clear communication to recipient managers of what precisely it was they needed to do to turn this years rating into a higher rating in the following year. In general, Finsoc managers could not do this. The situation at Premierco was quite different. There were often weekly, monthly or quarterly progress meetings and reviews. There was also the annual appraisal at which all employees completed a self-appraisal. This was shared with the reviewing manager who had completed an appraisal of the individual. The object was to reach a consensus; the output of the process was the setting of future objectives and planning training and development needs. Many managers talked of the major bene t of the system being `no surprises at the end of the year when the nal performance rating was announced. It seemed performance management was taken very seriously by managers at Premierco, where senior managers were convinced of its bene ts. The performance feedback process was the best example of the `new style managerialism which was evident at Premierco and was summarised by an enthusiastic operations manager:

I dont know anything at all about the technical side of the jobs my people do. I think its my job to manage them. I do that through talking to them about what they do and making sure everything is right for them to do their jobs. If you treat them correctly youll get that back 20 times over from them. They will want to do it for you.

Stage 4: translating performance into reward In none of the organisations did managers know what the nal PRP award was going to be until shortly before it was actually paid. In addition, they did not rate it as attractive when it was nally paid. A typical comment was from a Finbank business banking manager:

What would be nice is if you could say what your level of remuneration was going to be once you had achieved a certain level of performance. But the way that the system is now, you cant make that connection.

The situation was similar at Finsoc. For all managers this operated at two levels: they did not know what they would get and they were not sure what rating to give their staff. The amounts in recent years had been so small that managers generally were keen to push ratings as high as possible. The retail HR manager acknowledged this was a problem, but public declaration of the pot size, and therefore the payments associated with different ratings, would have been revealing managements negotiating hand to the trade union. The lack of money available to drive the performance management system at Finsoc exacerbated the major focus of managers dissatisfaction the lack of differentiation in the

72 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2

Philip Lewis, Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education

amount of award between the different levels of performance rating. There was a negligible difference between the cash amounts generated by different ratings. At Premierco, too, managers did not know what the award for a particular rating would be. This situation was brought about, partly, by the system which operated whereby awards were linked not only to performance but position on pay scale. Therefore a manager who was high on the scale received less PRP award for the same rating. It was also due to the fact the pay award was not declared until the latter part of the review year. Secondly, in recent years the size of awards had been small. This was due to the limited amount of money available for increases. There was some interview evidence which suggested this has led to some managers saying `if there is so little to give out, then why bother? Cascio (1989) and Lawler (1990) suggest that anything less than 10 per cent of salary is too little to be of consequence to employees. During the period of the eldwork, in all three organisations the maximum amount payable even to the outstanding performer was less than this amount. Communication Part of the PRP process entails communicating information to participants. Although not a major focus of the interview data, several points arose. One was the failure to communicate information about the awards which had been given, and a Finbank business manager explained this very clearly:

I... think those who achieve 2s and 1s [the top two ratings] ought to be publicised. This is so others could go to them and say: `What is it you did to make you a 1? I have asked this question of my manager, and frankly he doesnt know the answer. It is essential that managers are open and can say what it is that made the difference between the outstanding performer achieving all his targets and doing that something extra... This would enable the person to emulate the outstanding achiever. The more you open up the system to scrutiny the more accountable you make managers, and they should be accountable.

A good example of the mystique created by this lack of openness was related by a manager who did receive a 1 rating in 1994. When questioned about what he had to do to repeat the rating in the next year he replied:

I wouldnt get the same rating next year... nobody gets a 1 in two successive years. I dont know why they just dont.

There was no information conveyed to recipient managers about the general level of PRP awards at any level, either in the team, division, region or bank. As a consequence suspicion was evident. There was little evidence at Finsoc that there was any more communication about PRP than in Finbank. But there were two noteworthy perspectives which derive from the communication component of the PRP process cycle at Finsoc. First, the communication of society strategy to staff gave branch managers an impression of the broad frame of reference informing the performance feedback of the area manager. Secondly, a less positive point concerned the failure to communicate information regarding the general performance of other branch managers in the team and beyond in the wider organisation. This failed to provide managers with any benchmark of their own performance, a benchmark from which they may have derived self-esteem, solace or just satis ed curiosity. At Premierco the low level of awards which threatened PRPs productivity goals was a problem of which the company was very aware. Therefore much time was spent in managing the expectations of employees through employee communication. The economic position in which the company was placed was explained to all employees with the result

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2 73

Managing performance-related pay based on evidence from the nancial services sector

that those who had an increase in 1993 were pleasantly surprised. Like the other two organisations, the distribution of ratings at Premierco was not communicated to recipients. DISCUSSION The evidence outlined above indicates that the PRP process cycle was implemented ineffectively in Finbank and Finsoc, and only effectively in Premierco. But this raises the question: what do the data presented in this study add to existing insights on PRP theory and practice? This final section argues the case for the value of the process cycle as an analytical framework, questions the concern of writers with motivation theory, con rms the pre-eminence of the line manager in the management of PRP and reasons that the inclusion of pay in the performance management process may be unnecessary. Value of PRP process cycle Often the literature is clear in drawing the conclusion that PRP is unsuccessful, usually as measured by surveys which show employee discontent (eg Marsden and Richardson, 1992), but less clear about the reasons for this discontent. In adopting a processual analysis, this study has attempted to gain a clearer understanding of these reasons. In this respect the PRP process cycle has been helpful because of its ability to examine the functioning of the process links which deliver performance against objectives. As Guest (1997) asserts, with regard to recen t attempts in the literature to establish the effect of wider HRM practices on organisational performance (see Dyer and Reeves, 1995), without making explicit the possible linkages between cause and effect the understanding of the reasons for success or failure will not be understood. Guest (1997: 267) explains: `without some linkages... we have no theory. The PRP process cycle constitutes a theory; if the four stages are conducted effectively and information ows around the cycle, then PRP is more likely to be accepted by individuals and the objectives of the organisation in its introduction are more likely to be achieved. It is a highly deterministic theory and one, moreover, that takes no account of contingency theory, rightly a traditional concern of the pay literature (eg Lupton and Gowler, 1969). But it makes some advance in our thinking of why PRP may succeed or fail. This raises another question: what is meant by success or failure of PRP? This study follows the lead of Lawler (1984) in using the criterion of employee acceptance to determine the level of its success. Thus, the possible criteria of organisational objectives set for PRP in all three organisations these were unclear and impact on overall organisational performance because of the dif culty of isolating one HR component (Kessler and Purcell, 1995; Kinnie and Lowe, 1990) were rejected. In essence, the argument here is that if employees are generally in agreement with both the principle and practice of PRP, then they will be motivated to better job performance and bene cial organisational outcomes will follow. Conversely, if they are not in agreement with either the principle or the practice of PRP, then they will not be motivated to perform more effectively in their jobs and such organisational outcomes will not follow. Rather than improved job performance, the employee will feel at best apathetic, leading to PRP being largely ignored or alienated from both the PRP process and those responsible for its implementation (Gabris and Mitchell, 1988). Over three-quarters of the recipient managers interviewed at Finbank were extremely unhappy with both the principle and practice of PRP, so much so that the issue was the subject of a strike ballot soon after its introduction. Finsoc managers were less strident in their rejection; however, although generally accepting the principle of PRP, over two-thirds were unhappy with the way in which PRP was implemented. But at Premierco managers

74 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2

Philip Lewis, Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education

were overwhelmingly positive about PRP. They saw it as conducted fairly and perceived its congruence with the meritocratic values which the company had traditionally preached and they had absorbed. Therefore, using Lawler s (1984) criterion of employee acceptance, PRP could be said to be a success in Premierco but not in Finbank or Finsoc. In addition, only in Premierco was the PRP process cycle implemented effectively, giving some credence to the theory articulated above. Concern with motivation theory There is clear empirical evidence which suggests employee motivation is high on the list of organisations reasons for the introduction of PRP (Thompson, 1992; Cannell and Wood, 1992). Therefore it is only to be expected that the central concern of both researchers and practitioners is with the degree to which PRP has motivated employees to work in different ways in order to achieve a PRP award. This prompts questions about the extent to which PRP has provided an incentive for individuals to work harder, show more initiative, get work priorities right, increase the quality and quantity of work and whether the amount of award is suf cient to act as an incentive (Marsden and Richardson, 1992). These are perfectly valid concerns, but they have the effect of steering attention towards the `harder aspects of the cycle. The data from this study suggest that it is the `softer processes those which involve employees in the cycle rather than exclude them which are likely to be associated with greater acceptance of PRP. In Premierco this was the skilful giving of performance feedback, coaching to improve performance, gathering of performance data from a wide range of sources, negotiation of objectives and the management of expectations about the nal award. This suggests that, even if the pay element of the cycle (stage 4) is not accepted by employees, the processes which concern the determination of the award, if conducted effectively, may mitigate the unacceptable impact of the pay element. This was largely the case at Premierco. However, it must be said that existence of `new style managers at Premierco operating in a highly meritocratic culture played a signi cant part in promoting the effectiveness of the soft processes. This reinforces the earlier point about the importance of considering contingency theory in addition to the PRP process cycle theory. The Premierco context in which PRP took place was of considerable signi cance. Therefore, a virtuous circle was operating where effective PRP processes were rein forcing the meritocratic culture, thus further strengthening them. Pre-eminence of line managers It follows from the above that the effective implementation of the softer processes turns on the skills and attitudes of the line manager. This study has con rmed the conclusion of Storey (1992) that line managers have an important part to play in the HRM model of managing the employment relationship, of which PRP is often a signi cant component. They have a particularly important role in the implementation of PRP. As noted above, this role has a hard and a soft side. The hard side is detailed by ACAS (1996). It is line managers who must de ne the required standards of performance and behaviour, explain these to their subordinates, take tough decisions about assessments, communicate these decisions to subordinates and defend their judgements if asked. The soft side, exempli ed in this study by the new style managerialism evident at Premierco, is thought to be consistent with Guests (1987) HRM goal of employee commitment. It may be that there is an inherent contradiction between PRP and the soft goals of HRM. Driving employees to perform better by carrot and stick when they are excluded from the

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2 75

Managing performance-related pay based on evidence from the nancial services sector

process by dint of managers monopolising information setting objectives and standards and making assessments and awards (Marsden and Richardson, 1992) can hardly be thought of as a commitment seeking strategy. What this study has indicated is that, in two of the organisations, neither the hard nor soft aspects of the PRP process cycle were conducted effectively. This calls into question the attitudes and skill of the managers. The evidence suggested that short-term concerns, Storey and Sissons (1993: 76) `quick-fix agreements, fire-fighting solutions and Tayloristic job design methods which are built on command and control rather than the more timeconsuming consensus-seeking methods, governed the thinking and behaviour of these managers. The evidence from this study suggests that, if the softer elements of the PRP process cycle are to be promoted, then line managers need a longer term investment perspective on their management of employees, which will lead to the involvement of individuals in the process cycle rather than exclusion from it. CONCLUSION: `MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING The thrust of this discussion has been that the soft aspects of the PRP process cycle are those which have been given less attention in the literature, a shortcoming this article has sought to rectify. The argument has been that agreein g clear objectives, defining performance standards which emphasise how the job is done as well as the results of the job, monitoring progress towards objectives and feeding back to the employee the results of the monitoring in a developmental way are necessary pre-conditions for the acceptance of PRP by employees. But these activities could be part of a performance management process without the presence of pay. Indeed, these activities are consistent with what Bevan and Thompson (1991: 39) call `development driven integration, where the outcome of the performance management process is the identi cation of training and development needs. So is pay a necessary part of performance management? Certainly the recipient managers at both Finbank and Finsoc thought it doubtful. Even if all the hard and soft aspects of the PRP process cycle had been conducted effectively, the feeling still remained that an increase of 2 per cent was `much ado about nothing . But this study has shown that, when the PRP process cycle is conducted effectively as at Premierco, PRP is more likely to be accepted by employees than when it is conducted ineffectively, whatever the level of award. Note The author acknowledges with thanks the helpful comments of an unknown referee which guided the preparation of this article. REFERENCES ACAS. 1996. Appraisal Related Pay , London: ACAS. Bevan, S. and Thompson, M. 1991. `Performance management at the cross-roads. Personnel Management, November, 36-39. Cannell, M. and Wood, S. 1992. Incentive Pay: Impact and Evolution, London: Institute of Personnel Management and National Economic Development Of ce. Cascio, W. F. 1989. Managing Human Resources 2nd ed, New York: McGraw-Hill. Clark, G. 1995. `Performance management in Strategic Human Resource Management. C. Mabey and G. Salaman. Oxford: Blackwell. Dowling, B and Richardson, R. 1997. `Evaluating performance-related pay for managers in

76 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2

Philip Lewis, Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education

the National Health Service. International Journal of Human Resource Management. Vol. 8, no. 3, 348-366. Dyer, L. and Reeves, T. 1995. `Human resource strategies and rm performance: what do we know and where do we need to go? International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 63, 657-670. Gabris, G. T. and Mitchell, K. 1988. `The impact of merit raise scores on employee attitudes: the Matthew effect on performance appraisal. Public Personnel Management, Vol. 17, no. 4, 369-386. Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory, Chicago: Aldine. Guest, D. 1987. `Human resource managemen t and industrial relations . Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 24, no. 5, 503-521. Guest, D. 1997. `Human resource management and performance: a review and research agenda. International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 8, no. 3, 263-276. Hoevemeyer, V. A. 1989. `Performance-based compensation: miracle or waste? Personnel Journal, July, 64-68. Institute of Personnel Management. 1992. Performance Management in the UK , Wimbledon: Institute of Personnel Management. Kessler, I. 1994. `Performance pay in Personnel Management. K. Sisson (ed). Blackwell. Kessler, I. and Purcell, J. 1995. `Individualism and collectivism in theory and practice: management style and the design of pay systems in Industrial Relations: Theory and Practice in Britain. P. Edwards (ed). Oxford: Blackwell. Kinnie, N. and Lowe, D. 1990. `Performance related pay on the shop floor. Personnel Management, November, 45-49. Lawler, E. E. 1984. `The strategic design of reward systems in Strategic Human Resource Management. C. Fombrun, N. M. Tichy and M. A. Devanna. New York: John Wiley. Lawler, E. E. 1990. Strategic Pay: Aligning Organisational Strategies and Pay Systems , San Francisco: Jossey Bass. Lawler, E. E. 1995. `The new pay: a strategic approach. Compensation and Bene ts Review, July-August: 14-22. Lupton, T. and Gowler, D. 1969. `Selecting a wage payment system. Research paper 111. London: Engineering Employers Federation. Marsden, D. and Richardson, R. 1992. `Motivation and performance-related pay in the public sector: a case study of the Inland Revenue. Discussion Paper No. 75. Centre for Economic Performance. London School of Economics. McAdams, J. 1988. `Performance-based reward systems: towards a common fate environment . Personnel Journal, June, 103- 113. Procter, S, McArdle, L, Rowlinson, M, Forrester, P. and Hassard, J. 1993. `Performancerelated pay in operation: a case study from the electronics industry . Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 3, no. 4, 60-74. Snape. E, Redman, T. and Wilkinson, A. 1992 `Human resource management in building societies: making the transformation? Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 3, no. 3. Storey, J. 1992. Developments in the Management of Human Resources, Oxford: Blackwell. Storey, J. and Sisson, K. 1993. Managing Hum an Resources and Ind ustrial Relations , Buckingham: The Open University Press. Thompson, M. 1992. Pay and Performance: the Employer Experience, Falmer, Brighton: Institute of Manpower Studies.

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT JOURNAL VOL 8 NO 2

77

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Comparison Between HSBC - UK and Pakistan-Recruitment, Selection and Training Strategies To Gain The Competitive AdvantageDocument78 pagesA Comparison Between HSBC - UK and Pakistan-Recruitment, Selection and Training Strategies To Gain The Competitive Advantagenkhoso0% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Platero v. Baumer, 10th Cir. (2006)Document8 pagesPlatero v. Baumer, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Project Report On "Study of Performance Appraisal" Chapter I - Research MethodologyDocument3 pagesProject Report On "Study of Performance Appraisal" Chapter I - Research MethodologysagarnaikwadeNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Project Report Study and Evaluation of PDocument47 pagesProject Report Study and Evaluation of PVeekeshGuptaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Performance Appraisal, Performance ManagementDocument25 pagesPerformance Appraisal, Performance ManagementMoeshfieq WilliamsNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- 04 Chapter 4Document51 pages04 Chapter 4LONE WOLFNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Risk Culture Building White PaperDocument15 pagesRisk Culture Building White PaperRiskCultureBuilderNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Performance Management-2023Document24 pagesPerformance Management-2023sammie celeNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Activity 1 - 2 PADocument14 pagesActivity 1 - 2 PAquickzilver2010No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Organization and Management Reviewer PlanningDocument14 pagesOrganization and Management Reviewer PlanningJoaquin Angelo GazaNo ratings yet

- Process of EvaluationDocument28 pagesProcess of EvaluationNaeem JanNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Human Resources Management System McdonaldDocument6 pagesHuman Resources Management System McdonaldWaqas BaigNo ratings yet

- ApprasailDocument6 pagesApprasailAkanbi SolomonNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Chapter 5 Social Responsibility and Managerial EthicsDocument6 pagesChapter 5 Social Responsibility and Managerial Ethicsericmilamattim100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- PDF A Study On Performance Appraisal Strategy of Ultratech CementDocument102 pagesPDF A Study On Performance Appraisal Strategy of Ultratech CementSvl PujithaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- RetainingDocument34 pagesRetainingshush10No ratings yet

- HRM EnvironmentDocument31 pagesHRM Environmentjitukr100% (1)

- SchlumbergerDocument8 pagesSchlumbergerAb YayumNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Scope of HRMDocument2 pagesThe Scope of HRMTannu Priya VeeriniNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Effect of Organizational Culture and Employee Performance of Selected Banks in Anambra StateDocument11 pagesEffect of Organizational Culture and Employee Performance of Selected Banks in Anambra StateEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- OB TEST 1 Uppala Sri Charan 1106193003 CompleteDocument7 pagesOB TEST 1 Uppala Sri Charan 1106193003 CompletecharanNo ratings yet

- TKES Fact Sheets 7-11-2012 PDFDocument101 pagesTKES Fact Sheets 7-11-2012 PDFjen100% (1)

- Chapter 9 PowerpointDocument30 pagesChapter 9 PowerpointWanyi ChangNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Employee Handbook 2016 CrescendoDocument40 pagesEmployee Handbook 2016 CrescendoPrashant BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Sole-Sponsored Sales PromotionsDocument23 pagesSole-Sponsored Sales PromotionsSarah LubiganNo ratings yet

- Final Cadbury Project 1Document66 pagesFinal Cadbury Project 1Purva Srivastava70% (10)

- Management and Economics Journal: The Effect of Compensation On Satisfaction and Employee PerformanceDocument10 pagesManagement and Economics Journal: The Effect of Compensation On Satisfaction and Employee PerformanceAyesha RachhNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- MGT501 HRM FinalTermPapers Vuzs Team PDFDocument115 pagesMGT501 HRM FinalTermPapers Vuzs Team PDFAbbasKhanNo ratings yet

- Bcpp6e TB Ch01Document32 pagesBcpp6e TB Ch01Trần ĐứcNo ratings yet

- 4 - MBA565 - Performance MGT SystemDocument28 pages4 - MBA565 - Performance MGT SystemJaylan A ElwailyNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)