Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evaluation of St. Louis Streetcar by Jill Mead

Uploaded by

Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Evaluation of St. Louis Streetcar by Jill Mead

Uploaded by

Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVCopyright:

Available Formats

JILL MEAD

Evaluation of the St. Louis Streetcar Proposal

Mead |1

Introduction

Streetcar projects are proliferating across the United States. Spurred by the availability of federal funds and inspired by the success of projects in Portland and Seattle, city officials and interest groups are proposing a wide range of historic and modern streetcar projects that they hope will complement existing public transportation while catalyzing economic development. In March 2013, the Partnership for Downtown St. Louis released a feasibility study for a streetcar project to connect two major population and employment hubs in the city of St. Louis. The feasibility study recommended the project based on its high likelihood of achieving its two main objectives: 1) enhancing the regions transit system and 2) catalyzing economic growth throughout the streetcar corridor. This paper gives a background of the funding streams that support streetcar projects and weighs existing evidence that supports or contradicts the arguments advanced in the St. Louis Streetcar feasibility study. While it is clear that strategies to improve economic growth and public transportation are necessary in St. Louis, it is not clear that the St. Louis Streetcar project is the best use of public resources to achieve these goals.

Background: Why Streetcars? Why now?

According to the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), there is a wave of streetcar projects sweeping across the nation (LaHood, 2011). The Community Streetcar Coalition (CSC), consisting of representatives from local governments, transit authorities, engineering firms, and rail car manufacturers, held their 4th annual Streetcar Summit in Washington, D.C. in March 2013, where they presented a map of 32 Committed Streetcar Cities where projects are underway with partial or full funding (Appendix A) (Community Streetcar Coalition, 2013). The sudden desire to resuscitate streetcar networks can be attributed in part to the availability of specific federal funding streams to make these projects possible. The CSC formed in 2004, but the year of their first annual summit, 2009, coincided with three policy shifts and initiatives that enabled this new generation of streetcar projects to access federal funding for the first time. The first was the enactment of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in February 2009 which made $1.5 billion dollars available in discretionary grants as part of the Transportation Income Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) program. TIGER grants fund transportation projects considered to have a significant impact on a metropolitan area or region (Federal Highway Administration, 2013a). Additionally, the ARRA made available an additional $750 million available for new public rail systems and other fixed guideway systems as part of the existing New Starts program (Federal Transit Administration, 2009). The second policy shift was the Federal Transit Administration (FTA)s introduction of new evaluation criteria for New Starts and Small Starts applications in June 2009 as part of the DOTs Livability Initiative (Federal Transit Administration, n.d.). While New Starts projects were originally evaluated based on the four criteria of cost-effectiveness, mobility improvement, operational efficiencies, and environmental benefits, the new FTA criteria introduced two additional considerations: the transit-supporting land use (such as TOD) enabled by the project and its economic development effects. For New Starts and Small Starts programs, land use and economic development criteria were given equal weight as cost effectiveness, diminishing the role cost effectiveness played as a decisional criteria vis-a-vis other factors (Federal Transit

Mead |2

Administration, 2013b; Metro St. Louis, 2011). Cost effectiveness was further deemphasized when the DOT removed the requirement that New Starts projects rate a medium or higher on cost effectiveness in January 2010 (Freemark, 2009). Appendix B gives a graphical overview of current New Starts decision criteria. The third initiative was the announcement in December 2009 that the FTA would disburse $130 million in funds for the Urban Circulator program for systems such as streetcars and rubber-tire trolley lines [that] provide a transportation option that connects urban destinations and foster the redevelopment of urban spaces into walkable mixed use, high density environments (Federal Transit Administration, n.d.). Although Urban Circulator funds were part of the New Starts and Small Starts program, each grant was limited to $25 million, and was evaluated based on its potential to enhance quality of life through improving transportation access and choice (livability), environmental sustainability, its potential to foster redevelopment in adjacent parcels, and the extent to which it leverages public-private partnerships (Federal Transit Administration, n.d.). The combination of the influx of funding, along with the relaxation of funding criteria which had previously excluded streetcar projects from consideration due to their low costeffectiveness ratings, created a funding environment favorable to cities interested in building their own streetcar lines. While from 2005-2009, no streetcar projects were funded with New Starts funds (Freemark, 2009), from 2010-2012, the DOT provided almost $350 million in funding for 11 streetcar and urban circulator projects across the country (LaHood, 2012).

The Streetcar Comes (Back) to St. Louis

In the city of St. Louis, two streetcar projects are underway. The first, known as the Loop Trolley, represents a collaborative effort between the City of St. Louis, adjacent inner-ring suburb University City, the non-profit Citizens for Modern Transit, and developer Joe Edwards (Citizens for Modern Transit, n.d.). The Loop refers to Delmar, a street close to Washington University that attracts students, tourists, and residents to restaurants and retailers that once served as a terminal loop for one of St. Louis many 20th century streetcars. The primary purpose of the project is to revitalize and cultivate development on Delmar, making an eastern extension of the Loop district possible (Citizens for Modern Transit, n.d.). The idea of building a streetcar in the Loop to attract development was introduced for the first time in 1997, and a feasibility study was conducted in 2000. In 2007, the City of St. Louis and University City established the Loop Trolley Transportation Development District (TDD), and in 2010, a federal grant was awarded for the design of the project. In 2011, an environmental assessment (EA) concluded that there was no significant impact expected from the project. The project received final approval in 2012 and was awarded a $25 million grant under the Urban Circulator Program (Citizens for Modern Transit, n.d.). The 2.2 mile Loop Trolley system could be operational by summer 2014 (Rottermund, 2013). Meanwhile, six miles east of the Loop, The Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, a nonprofit composed of representatives of downtown businesses, the City of St. Louis, Washington University, and Citizens for Modern Transit recently released a feasibility study for a second,

Mead |3

more ambitious streetcar project. The proposed St. Louis Streetcar, if completed, will consist of two alignments totaling seven miles (Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013). The east-west alignment will extend for five miles, connecting the Central West End (CWE), a residential and employment hub and site of Washington Universitys Medical and Biotech Campuses, with downtown St. Louis. The proposed north-south alignment is 1.9 miles long and connects the distressed residential neighborhood north of downtown with the Multimodal Transportation Center located at the Civic Center station of St. Louis light rail system, MetroLink. The overall cost of the project is estimated between $218 and $271 million, and operating costs are estimated at $9.7 million. The project will seek up to fifty percent of its capital costs from the federal government, and the study proposes a number of local funding strategies for the local contribution (Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013). The justification for the streetcar project rests on two central assumptions. The first is that it will strengthen the regions overall transportation network, attracting new choice riders not only to the streetcar corridor, but to the network overall, leading to a reduction in automobile traffic and improved air quality. The second claim for the new streetcar is that it will increase population and jobs in the corridors, thereby catalyzing and supporting future development. According to the objectives laid out in the feasibility study:

The streetcar is intended to provide a convenient connection to large numbers of jobs, residences, and major destinations. It is designed to be an important part of the regions overall transit system. And, reflecting the impact of other modern streetcars in the United States, it is designed to have a major impact on economic development throughout the corridor (Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013, p. 2).

These complementary objectives reflect the intention of the project, which is based upon the reciprocal relationship between land use and transportation. Although existing densities at each pole of the alignment are used to justify the project, part of the idea behind the streetcar plan is that it will induce some of the development and density along the corridor that is necessary to support high ridership. Initial ridership estimates depend on the relation of existing land use to transportation, while future ridership estimates depend on the streetcars ability to catalyze additional transit-supportive development. This paper will concentrate on the east-west corridor connection in particular, considering the extent to which research and the local context support the ability of the streetcar project to enhance the regions transit system and produce economic development impacts.

A convenient connection

The argument for building the streetcar to connect Central West End to Downtown is that it links two major employment centers with residential neighborhoods and local destinations. Although the feasibility study states that density drives transit ridership (The Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013), the project area falls outside of the area of the greatest population density in St. Louis. Although Downtown and the CWE have high concentrations of daytime employment (88,000 in Downtown and 30,000 in the CWE) (The Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013), those who work downtown currently commute from at least seven neighboring counties, greatly beyond the reach of existing public

Mead |4

transportation networks (Appendix C). Furthermore, residential densities, while high in some of the census blocks in the project area, do not represent the areas of highest residential population concentration within the City of St. Louis. Appendix D shows a map of census blocks in St. Louis city by density. From the map, it is clear that the southeastern portion of the city contains the largest number of contiguous census blocks with population densities greater than or equal to 9,000 people per square mile (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). An analysis of trip production and attraction published by the East-West Gateway Council of Governments (EWGCOG), the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), showed that the Southside study area produced 88,405 person trips with the Central Business District as a destination every day in 1996, the greatest number of Central Business District trips of all study areas (EWGCOG, 1999). Rather than building a streetcar to connect the CWE to downtown, a southern connection would create a convenient connection by enabling a new rail connection between the area of the greatest population density in the region and the area of the greatest employment density. This would serve the greatest number of people, a precondition for high ridership. With respect to the rest of the existing public transportation network, it is important to note that the proposed streetcar alignment duplicates service which is already provided by MetroLink, St. Louis light rail service. MetroLink opened in 1993, and today consists of two lines totaling 46 miles in length, with nine stops within the City of St. Louis and 37 stations overall (Metro St. Louis, 2013). Appendix E shows the proposed streetcar alignment in relation to the existing MetroLink route. As shown on the map, the MetroLink connects the CWE to downtown, as well as provides connections to a number of local attractions: the airport, Washington University, St. Louis University, the University of Missouri-St. Louis, the baseball stadium, Forest Park, the Multimodal Transportation Center, the Convention Center, and destinations in Illinois such as Scott Air Force base. An average of 54,000 riders used MetroLink on weekdays in 2012, with the greatest number of average daily weekday boardings taking place at the CWE stop (Citizens for Modern Transit, 2012). While the initial alignment and 2001 expansion into Illinois were each funded at approximately 75% by the FTA and 25% locally, the 2006 expansion was funded entirely with bonds. St. Louis City and County residents support MetroLink operation and expansion through local sales tax increases approved by voters in 1997 (St. Louis City) and 2010 (St. Louis County), which collected $83 million per year in 2011 (Mares & Rothman-Shore, 2012). Despite local support and interest in MetroLink expansion, especially into the regions most dense residential areas north and south of downtown, progress to expand service has been slow due to lack of state and federal funding (Metro St. Louis, n.d.). In 2000, the EWGCOG conducted Major Transportation Investment Analyses (MTIAs) for the Northside and Southside corridors, and conceptual designs were prepared in 2007 (EWGCOG, 2010). Appendix F provides a map of the current system (indicated in green and red) along with the proposed Southside (purple) and Northside (orange) alignments. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the streetcars north-south alignment overlaps with the alignment chosen for Northside MetroLink expansion. Therefore, the proposed St. Louis Streetcar project does not demonstrate compatibility with the existing rail network nor the plans for expansion being made at the regional level. Rather than solicit federal funding for a new fixed guideway transportation mode, it makes more sense for the Partnership for

Mead |5

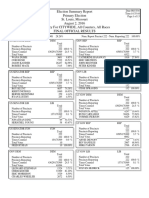

Downtown St. Louis to support MetroLink expansion efforts, which would provide a greater benefit in terms of transportation options for St. Louis residents. Although it is said that streetcar projects provide comparable development benefits as light rail at a lower cost1, in the case of the St. Louis Streetcar, the streetcar project, however less expensive than light rail, does not provide any travel time benefits for users. Table 1 below gives a comparison of travel times along the proposed east-west corridor.

Table 1. Comparison of travel times along the proposed east-west corridor

Mode Auto Auto MetroLink Bus St. Louis Streetcar Route Streetcar route: Central West End MetroLink Station to th 8 and Pine MetroLink Station Fastest route: I-64 E and local streets Central West End Station to 8 and Pine Station #10 Gravois-Lindell Lindell & N. Taylor to Tucker and Olive th Central West End MetroLink Station to 8 and Pine MetroLink Station

th

Travel time 2 18 minutes 11 minutes 11 minutes 23 minutes 40 minutes

2

Headways n/a n/a 10-15 minutes 30-40 minutes 10-15 minutes

As seen in the table, it is nearly four times as fast to use the existing MetroLink system to make the trip between the CWE and downtown, although the MetroLink offers no stations along the proposed streetcar alignment between the two destinations. The feasibility study predicts that the new east-west streetcar line will attract 5,900 passengers per weekday, a figure considered high by U.S. streetcar standards (The Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013). The plan also predicts that an additional 2,700 passengers will be attracted to the overall transit system as a result of the streetcar (The Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013). In light of the travel time disparity between MetroLink and the streetcar, it is problematic that the feasibility study estimates travel demand using current MetroLink ridership estimates, although the feasibility study acknowledges that few trips between CWE to downtown will divert to the streetcar due to travel time (Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013). It is important to note that, even if development benefits are realized along the corridor as a result of the streetcar project, the project represents a lost opportunity to use transportation investment funding to

Although it is more logical from a service-provision perspective to concentrate on expanding the existing light rail network, streetcar projects are often promoted as providing the economic development benefits of a fixed rail network at a lower cost than light or heavy rail projects. Streetcar projects often cost much less per mile because they run along existing streets, negating the need for expensive acquisition of exclusive right-of-way. The American Public Transportation Association (APTA) reports costs of $12.4 million per mile in Portland, $13.7 million per mile in Tampa, $7.1 per mile in Little Rock, and $4 million per mile in San Pedro California, while recommending that streetcar projects should not cost more than $10 million per mile (Weyrich & Lind, n.d.). Similarly, they recommend a maximum cost of $20 million per mile for light rail projects (Weyrich & Lind, n.d.); Light Rail Centrals list of North American light rail projects gives a range of $15 million to over $100 millio n per mile (Middleton, 2002). The St. Louis MetroLink is listed at $27 million per mile (Middleton, 2002), while the Loop Trolley will cost about $20 million per mile to build (Logan, 2012), in both cases exceeding APTA recommendations.

2 3

Google Maps, 2013 Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013

Mead |6

make the St. Louis transportation network more efficient through the decrease of public transportation travel times.

Major impact on economic development

The second of the two arguments for enhancing the St. Louis transportation network with a streetcar is that reflecting the impact of other modern streetcars in the United States, it is designed to have a major impact on economic development throughout the corridor (Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013, p. 2). This objective reflects the second direction of the reciprocal land use-transportation relationship, in which transportation affects the way in which parcels of land are zoned by planning departments and valued and developed by private interests. In some cases, negative externalities such as noise and pollution lead to lower demand for adjacent parcels, while in other cases, access benefits result in higher demand. This relationship has been documented for highways (Carey & Semmens, 2003), heavy rail (Cervero & Landis, 1997), BRT (Rodrguez & Targa, 2004), light rail stations and bus stops (Pan, 2013), and even greenways (Lindsey, Man, Payton & Dickson, 2004), but there is limited evidence to date about the impacts of modern streetcar projects on development and property values. Furthermore, it is important to note that the success of development projects along streetcar corridors can be attributed to a number of broader contextual factors. The St. Louis Streetcar feasibility study alludes to these factors on page 7 of the report:

Building a transit [sic] does not necessarily mean the development will happenIf combined withproper zoning, [and] policy and incentives, streetcars can help to spur development. This has been documented in Portland and Seattle. Cities where streetcars have not seen the expected ridership or development typically have not provided serious transit with frequent headways and connections to employment concentrations. (Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013, p. 7)

This section of the paper will discuss evidence for a streetcar-land use connection and how generalizable that evidence is to St. Louis, given a number of contextual factors specific to St. Louis. Proponents of the St. Louis Streetcar and Loop Trolley both cite the Portland and Seattle examples to give evidence that streetcars lead to economic development. To date, there are few rigorous studies to examine this assertion. A 2005 non-peer-reviewed study by Hovee et al. analyzed the impact of the first of Portlands two streetcar lines, which opened in 2001. The study compared development prior to the construction of the alignment in 1997 with development following its opening from an unspecified year. They found an increase in the percent of the floor area ratio (FAR) utilized within one block of the streetcar, with 90% of FAR developed within one block of the streetcar line, decreasing to 43% at distances of greater than three blocks. They also found that, pre-streetcar, the land located within one block of the alignment captured 19% of development, while in the post-streetcar period, it increased to 55% of development (Hovee et al., 2008). They estimated the impact of new development at more than $2.4 billion. The authors caution that their analysis is not derived from regression or hedonic techniques; furthermore, they attribute development to other key factors such as

Mead |7

development agreements with property owners and consolidated land ownership (Hovee et al., 2008). Similarly, Seattle also experienced increases in parcel development and property values along streetcar alignments, although separating the effect of concurrent economic development efforts from those directly attributable to the streetcars presence remains difficult. For example, Seattles South Lake Union streetcar was proposed in 2003, approved in 2005, and opened in 2007 (Bogren, 2009). However, prior to 2003, a number of public and private efforts were underway to develop the South Lake Union neighborhood due to pressure on existing land uses in the area and the citys desire to develop the area into a biotech and software development hub (City of Seattle, 2012). Throughout the 1990s, high-profile developers such as Vulcan, headed by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, acquired nearly half of the areas parcels for future development and in the early 2000s, Vulcan approached city officials with the streetcar proposal to extend public transportation into the area (City of Seattle, 2012). Today, average daily ridership is 1,738 (City of Seattle, 2013), and property values have increased, but it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate the role of the streetcar from the role of the other factors at work (Brookings Institute, 2009). In Tampa the streetcar line was seen as a means of connecting an average of 1,000 residents and tourists per weekday to destinations in historic Ybor City and the recentlyredeveloped, formerly-industrial Channel District. In the case of Tampa, the transportation connection is critical to support the entertainment district (Tampa Bay Times, 2012), which is otherwise cut off from downtown and Ybor City by an interstate. A 2009 Brookings Institution which considered the economic impact of the Portland, Seattle, and Tampa streetcar projects demonstrated property value increases in some areas of over 400%; however, four key findings provide further detail about the property appreciation process. First, all three neighborhoods were located close, but just outside of walking distance, from their respective cities downtowns. Secondly, all three neighborhoods were underutilized, making them targets for developers, as well as targets for any number of citizen and city goals (Brookings Institution, 2009, p. 16). Third, residential property values increased more slowly than commercial and industrial property values. In the case of Portland, existing homes did not increase in value until after service began (Brookings Institution, 2009). Fourth, vacant land had the fastest rate of appreciation, while commercial properties increased more slowly than industrial, multi-family, or vacant land. The Brookings Institution report concludes that the underlying theme of the three case studies was the ability of the streetcar line to connect places that were just out of walking distance from other urban districts, and that the availability of easily-changed and inexpensive districts also played a major contributing role to the magnitude of property value growth observed in each case. Therefore, its clear that economic growth in Seattle, Portland, and Tampa could be traced to sources beyond the streetcar alone. The Seattle case study highlights the importance of public-private partnerships, and the Brookings Institution report highlights the placement and relative development of the district to be developed in relation to the rest of the city. One factor that is not explicitly discussed in the report is the broader economic growth of the three cities. All three cities have experienced population growth within the past 20 years which may

Mead |8

have intensified demand for development in general. Comparing the growth of Portland, Seattle, and Tampa with St. Louis (Table 2) indicates that there are factors in St. Louis that have led to population loss over the past two decades.

Table 2. Population profiles of Portland, Seattle, Tampa, and St. Louis City Portland Seattle Tampa St. Louis 2010 population 583,776 608,660 335,709 318,172 % change 1990-2000 +21.0% +9.1% +8.4% -12.2% % change 2000-2010 +10.3% +8.0% +10.6% -8.3% % vacant housing 2012 (MSA)4 7.0 8.1 20.8 14.5

In fact, St. Louis city has registered lost population with each census since 1950, and today suffers from high crime rates and a troubled public school system that make it unattractive to potential residents. Therefore, there may be far less development demand in general in St. Louis than in Portland, Seattle, and Tampa. The St. Louis Streetcar feasibility study asserts that [t]he streetcar will increase population and employment in the corridor (Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013, p. 6), but it does not specify if the population or employment will relocate from other locations in the city, the region, or from outside of the region, each of which has very different implications for the citys economy. Similarly, while the Brookings Institute report describes and quantifies economic growth in the Portland, Seattle, and Tampa corridors, they did not provide information about where population and employers relocated from. In the absence of coordinated (and successful) efforts to attract population or employers from outside the St. Louis region, it is possible that developing the streetcar corridor may only attract and shape development that may have taken places in other parts of the city, resulting in little net growth for the city or region overall. Understanding the impact of streetcars requires more thorough and rigorous study of projects as they are realized, concentrating on contextual factors that help to explain the success of failure of projects to meet economic development goals. The implementation of projects in cities that more closely resemble St. Louis in terms of population loss and other challenges can likewise provide insight that can guide the development of transportation projects in peer cities. In addition to studying the impact of streetcars in other cities, it is possible to study the impact of MetroLink on property values within St. Louis. Unfortunately, to date there has no rigorous study of the relationship between land value appreciation and MetroLink stations. While Metro St. Louis reports over $2 billion in development near its station, there is little transit-oriented development (TOD) around city MetroLink stations. One factor that complicates the development of TOD is that the initial MetroLink alignment made use of unused and underused railroad right-of-way, some of it dating from the 19th century, meaning that some stations are located in formerly-industrial corridors and viaducts. In recognition of need for greater emphasis on TOD, Metro St. Louis released a Best Practices Guide for TOD in

4

http://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/data/ann12ind.html

Mead |9

the St. Louis region in 2011. Some of the barriers to TOD development identified in the guide could be expected to hold true for streetcar-driven TOD, such as low land values which facilitate suburban greenfield-style development and inhibit dense urban infill development (Metro St. Louis, 2011). Existing land use and zoning codes which promote suburban-style development are mentioned, as is the limited experience of public and private sector in the planning, finance, and construction of TOD. Despite challenges, the guide considers St. Louis well-positioned to integrate land use policy and transit planning in support of TOD (M etro St. Louis, 2011, p. 15). At present, the EWGCOG is hosting a series of public meetings to develop a master plan for TOD around MetroLink stations (Citizens for Modern Transit, 2013). Given Metros difficulty in encouraging TOD around stations, it is clear that development along a streetcar alignment in St. Louis would likewise not occur without a number of public and private stakeholders working actively to address barriers to transportation-related development.

Conclusion

Streetcar projects are often justified by their potential to strengthen a citys transportation network while simultaneously encouraging development and increasing property values. In the case of St. Louis, it is hoped that the placement of the streetcar line would send a strong signal to developers, who will in turn build housing and commercial buildings, increasing the property tax base and population of the corridor for the benefit of the city. In addition to its economic development benefits, it is expected that the streetcar will improve the regions transportation network by providing new, attractive public transportation connections (Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013). While the St. Louis Streetcar Feasibility Study is optimistic about the achievement of these two objectives, reviewing the study calls some of their claims into question. Ridership estimates seem inflated given the slow travel speeds of the streetcar and methodology used. The choice of alignment fails to prioritize the citys densest areas and is out of sync with plans being made at the regional level. In terms of the streetcars ability to catalyze economic development in St. Louis, the study inadequately addresses the wide variety of contextual factors, such as land use policy and the existence of strong public-private partnerships and market demand that were characteristic of other cities success in attracting development to streetcar corridors. However, even in cities where streetcar projects were considered successful, no rigorous studies of streetcar project implementation and economic growth have been conducted. Even if such studies were available, inferring conclusions about the role of the streetcar would be complicated by a number of confounding factors, and it might not be possible to generalize results to other cities. While it is clear that strategies to improve economic growth and public transportation are necessary in St. Louis, it is not clear that the St. Louis Streetcar project is the best use of public resources to achieve these goals. It is possible to increase livability, economic vitality, and quality of life through the provision of transportation, but it is important that plans to do so carefully consider local context and regional priorities.

M e a d | 10

References

Bogren, S. (2009). The South Lake Union Streetcar. Community Transportation Association Magazine. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://web1.ctaa.org/webmodules/webarticles/articlefiles/South_Lake_Union_Streetcar.pdf The Brookings Institution. (2009). Value Capture and Tax-Increment Financing Options for Streetcar Construction. Carey, J., & Semmens, J. (2003). Impact of highways on property values: case study of superstition freeway corridor. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1839(1), 128-135. Cervero, R., & Landis, J. (1997). Twenty years of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System: Land use and development impacts. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 31(4), 309-333. Citizens for Modern Transit. (n.d.) Loop Trolley [website]. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://www.looptrolley.org/index.html Citizens for Modern Transit. (2012, October 3). Metro Ridership in August. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://cmt-stl.org/metro-ridership-in-august/ Citizens for Modern Transit. (2013, April 11). 5 Transit-Oriented Development Public Meetings Set for Next Week. Accessed April 24, 2013 from http://cmt-stl.org/5-transit-oriented-development-publicmeetings-set-for-next-week/ City of Seattle. (2013). Sponsorship Information. Seattle Streetcar [Website]. Accessed April 22, 2013 from http://www.seattlestreetcar.org/sponsor.htm Community Streetcar Coalition. (2013). 2013 Streetcar Coalition Summit. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://streetcarcoalition.org/ East-West Gateway Council of Governments. (1999). Southside Corridor: Existing and Future Conditions Document. Prepared by Parson Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://www.ewgateway.org/pdffiles/library/trans/metrolink/ExistingAndFutureConditions-ss.pdf East-West Gateway Council of Governments. (2009). Commute to Downtown St. Louis [Map]. Accessed April 22, 2013 from http://www.ewgateway.org/pdffiles/maplibrary/CommuteDowntownTrip0909.pdf East-West Gateway Council of Governments. (2010). Current Status of Planning and Implementation Activities of MetroLink Corridors. Accessed April 22, 2013 from http://www.ewgateway.org/trans/MetroLink/StatusTable/statustable.htm Federal Transit Administration. (n.d.). Frequently Asked Questions: Urban Circulator. U.S. Department of Transportation. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://www.fta.dot.gov/about/about_FTA_11006.html

M e a d | 11 Federal Transit Administration. (2009). American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. U.S. Department of Transportation. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://www.fta.dot.gov/grants/13951.html Federal Transit Administration. (2013a). TIGER Discretionary Grants. U.S. Department of Transportation. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight/infrastructure/tiger/ Federal Transit Administration. (2013b). Capital Investment Program FY 2013 Annual Report Evaluation and Rating Process. U.S. Department of Transportation. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://www.fta.dot.gov/documents/FY13_Evaluation_Process.pdf. Freemark, Y. (2009, December 18). Lowering CEI Guidelines Will Limit the FTAs Effectiveness in Choosing Projects. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://www.thetransportpolitic.com/2009/12/18/lowering-cost-effectiveness-guidelines-will-limitthe-ftas-effectiveness-in-choosing-projects/ Google Maps. (2013). [Central West End MetroLink Station to 8th and Pine MetroLink Station] [Directions]. Retrieved from maps.google.com Hovee, E.D. and Company, LLC. (2008). Streetcar-Development Linkage: The Portland Streetcar Loop. Revised Draft. Prepared for City of Portland Office of Transportation. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://reconnectingamerica.org/assets/Images/Hovee-Report-Eastside-2008.pdf LaHood, R. (2011, February 24). Streetcar Revival Means More Mobility, More American Jobs. The Official Blog of the U.S. Secretary of Transportation. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://fastlane.dot.gov/2011/02/streetcar-revival-means-more-mobility-more-americanjobs.html#.UW_-2Vf75AE LaHood, R. (2012, January 12). American Streetcar Projects Creating Jobs Today, Liveable Communities and Economic Development Tomorrow. The Official Blog of the U.S. Secretary of Transportation. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://fastlane.dot.gov/2012/01/streetcar-forum.html#.UXAsMFf75AE Lindsey, G., Man, J., Payton, S., & Dickson, K. (2004). Property values, recreation values, and urban greenways. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 22(3), 69-90. Logan, T. (2012, October 8). Will Streetcar Really Extend Loop Development in St. Louis? St. Louis PostDispatch Electronic Edition. Accessed April 21, 2013 from http://www.stltoday.com/business/columns/building-blocks/will-street-car-really-extend-loopdevelopment-in-st-louis/article_35273492-0f3a-11e2-8c95-001a4bcf6878.html Mares, R., & Rothman-Shore, A. (2012). Case Study: 2010 St. Louis County Initiative to Pass a Transit Tax (Prop A). Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy. Accessed April 21, 2013 from http://www.northeastern.edu/dukakiscenter/wp-content/uploads/Lessons-Learned-Brief-2010-StLouis-Prop-A-Campaign-9-20-2012.pdf

M e a d | 12 Metro St. Louis. (n.d.). Metro Moves Community. Accessed April 22, 2013 from http://www.metrostlouis.org/About/MetroMovesCommunity.aspx Metro St. Louis. (2011). St. Louis Regional Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Best Practices Guide. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://www.metrostlouis.org/Libraries/TOD_Documents/TOD_Best_Practices_Guide.pdf Metro St. Louis (2013). Maps & Schedules: MetroLink. Accessed April 20, 2013 from http://www.metrostlouis.org/PlanYourTrip/MapsSchedules/MetroLink.aspx Middleton, J. (2002) Status of North American Light Rail Projects. Light Rail Central. Accessed April 21, 2013 from http://www.lightrail.com/projects.htm NextStL. (2005). Transportation Projects: Metrolink Expansion? Accessed April 21, 2013 from http://nextstl.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=29&t=670 Pan, Q. (2013). The impacts of an urban light rail system on residential property values: a case study of the Houston METRORail transit line. Transportation Planning and Technology, 36(2), 145-169. Partnership for Downtown St. Louis. (2013). St. Louis Streetcar Feasibility Study. Accessed April 15, 2013 from http://www.downtownstl.org/docs/StLouisStreetcarFeasibilityStudy-Final.pdf Rodrguez, D. A., & Targa, F. (2004). Value of accessibility to Bogota's bus rapid transit system. Transport Reviews, 24(5), 587-610. Rottermund, M. (2013, March 12). Loop Trolley CUP Approved; Line Could Be in By Summer 2014. University City Patch. Accessed April 21, 2013 from http://universitycity.patch.com/articles/looptrolley-cup-approved Tampa Bay Times. (2012, September 19). Tampas Streetcar of Desire. A Times Editorial. Accessed April 22, 2013 from http://www.tampabay.com/opinion/editorials/tampas-streetcar-of-desire/1252385 U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Social Explorer. Census 2010 PL94 Maps. Retrieved April 18, 2013 from www.socialexplorer.com U.S. Census Bureau. (2012). Annual Statistics: 2012. Table 8. Gross Vacancy Rates for the 75 Largest Metropolitan Statistical Areas. Accessed April 22, 2013 from http://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/data/ann12ind.html Weyrich, P.M., & Lind, W.S. (n.d.) What Does It Cost? From Bring Back the Streetcars! A Conservative Vision of Tomorrows Urban Transportation. American Public Transportation Association Streetcar and Heritage Trolley Site. Accessed April 18, 2013 from http://www.heritagetrolley.org/artcileBringBackStreetcars7.htm

M e a d | 13

Appendices

Appendix A Community Streetcar Coalition Map of Committed Streetcar Cities (2013)

Source: Community Streetcar Coalition, 2013

M e a d | 14 Appendix B New Starts funding criteria

Source: Metro St. Louis, 2011

M e a d | 15 Appendix C Origin of commute trips to downtown St. Louis

Source: EWGCOG, 2009

M e a d | 16 Appendix D Population density by census block, St. Louis City, 2010, compared to proposed streetcar trajectory (dashed line)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 & Social Explorer

M e a d | 17 Appendix E Map of proposed St. Louis streetcar route and existing MetroLink route

Central West End Station

8 and Pine Station (Downtown)

th

Source: Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, 2013

M e a d | 18 Appendix F Map of Existing, Future, and Potential Missouri MetroLink Alignments

Source: NextStL, 2005.

You might also like

- AGENDA4-2017-2018 1stDocument12 pagesAGENDA4-2017-2018 1stAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Mar 2016 Final Unofficial ResultsDocument1 pageMar 2016 Final Unofficial ResultsAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Special House Investigative Committee On Oversight - ReportDocument25 pagesSpecial House Investigative Committee On Oversight - ReportKevinSeanHeldNo ratings yet

- Adler Lofts Vs Locust Business District Final Judgment June 20, 2017Document16 pagesAdler Lofts Vs Locust Business District Final Judgment June 20, 2017Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Mar 2016 Final Unofficial All 28 WardsDocument28 pagesMar 2016 Final Unofficial All 28 WardsAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Aug16 Final Official SummaryDocument13 pagesAug16 Final Official SummaryAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Franks V Hubbard Opinion ED104797Document17 pagesFranks V Hubbard Opinion ED104797Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- AGENDA4-2017-2018 2ndDocument12 pagesAGENDA4-2017-2018 2ndAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Unofficial List of Candidates Rev. 11-27-12Document5 pagesUnofficial List of Candidates Rev. 11-27-12Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Aug16 Citywide Precinct Breakdown PDFDocument3,144 pagesAug16 Citywide Precinct Breakdown PDFAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Aug16 Citywide Precinct Breakdown PDFDocument3,144 pagesAug16 Citywide Precinct Breakdown PDFAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- 2011 Citywide Ward Map 1Document1 page2011 Citywide Ward Map 1Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Final Judgement On The Bruce Franks v. Penny Hubbard CaseDocument22 pagesFinal Judgement On The Bruce Franks v. Penny Hubbard CaseSam ClancyNo ratings yet

- Election Summary Report Primary Election St. Louis, Missouri August 2, 2016 Summary For WARD 1, All Counters, All Races Final Unofficial ResultsDocument116 pagesElection Summary Report Primary Election St. Louis, Missouri August 2, 2016 Summary For WARD 1, All Counters, All Races Final Unofficial ResultsAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- 1101 Locust 2006 Quit Claim DeedDocument2 pages1101 Locust 2006 Quit Claim DeedAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Civic Center Site Plan 042016Document1 pageCivic Center Site Plan 042016Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- GMAB Appointee Terms 11-27-12Document2 pagesGMAB Appointee Terms 11-27-12Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Transit Oriented Development Study For Proposed Northside-Southside AlignmentDocument265 pagesTransit Oriented Development Study For Proposed Northside-Southside AlignmentAmy LampeNo ratings yet

- 80 SouthamptonDocument1 page80 SouthamptonAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- GMAB Appointee Terms 10-16-13 FORGEDDocument2 pagesGMAB Appointee Terms 10-16-13 FORGEDAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Lewis Reed PollDocument1 pageLewis Reed PollAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Unofficial List of Candidates (Rev. 3-14-16)Document26 pagesUnofficial List of Candidates (Rev. 3-14-16)Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Soldiers' Memorial Aerial RenderingDocument1 pageSoldiers' Memorial Aerial RenderingAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Bike STL Map 2015Document2 pagesBike STL Map 2015Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Proposed Quik Trip Site PlanDocument1 pageProposed Quik Trip Site PlanAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- 2009-2010 Seniority ListDocument1 page2009-2010 Seniority ListAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Unofficial List of Candidates Rev 11-24-14Document5 pagesUnofficial List of Candidates Rev 11-24-14Anonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four: Vision FrameworkDocument18 pagesChapter Four: Vision FrameworkAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Aloe PlazaDocument2 pagesAloe PlazaAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- 3 Chapter Three: Summary of Alternatives AnalysisDocument10 pages3 Chapter Three: Summary of Alternatives AnalysisAnonymous 0rAwqwyjVNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- ManuscriptDocument2 pagesManuscriptVanya QuistoNo ratings yet

- Symbolic InteractionismDocument8 pagesSymbolic InteractionismNice tuazonNo ratings yet

- Serto Up To Date 33Document7 pagesSerto Up To Date 33Teesing BVNo ratings yet

- Ir Pc-1: Pre-Check (PC) Design Criteria For Freestanding Signs and Scoreboards: 2019 CBCDocument15 pagesIr Pc-1: Pre-Check (PC) Design Criteria For Freestanding Signs and Scoreboards: 2019 CBCAbrar AhmadNo ratings yet

- 50 Ways To Balance MagicDocument11 pages50 Ways To Balance MagicRodolfo AlencarNo ratings yet

- AD 251 - Equivalent Uniform Moment Factor, M (Italic)Document1 pageAD 251 - Equivalent Uniform Moment Factor, M (Italic)symon ellimacNo ratings yet

- New Japa Retreat NotebookDocument48 pagesNew Japa Retreat NotebookRob ElingsNo ratings yet

- Seminar 6 Precision AttachmentsDocument30 pagesSeminar 6 Precision AttachmentsAmit Sadhwani67% (3)

- Amway Final ReportDocument74 pagesAmway Final ReportRadhika Malhotra75% (4)

- Leks Concise Guide To Trademark Law in IndonesiaDocument16 pagesLeks Concise Guide To Trademark Law in IndonesiaRahmadhini RialiNo ratings yet

- FED - Summer Term 2021Document18 pagesFED - Summer Term 2021nani chowdaryNo ratings yet

- PPM To Percent Conversion Calculator Number ConversionDocument1 pagePPM To Percent Conversion Calculator Number ConversionSata ChaimongkolsupNo ratings yet

- Self Healing Challenge - March 2023 Workshop ThreeDocument16 pagesSelf Healing Challenge - March 2023 Workshop ThreeDeena DSNo ratings yet

- Health Optimizing Physical Education: Learning Activity Sheet (LAS) Quarter 4Document7 pagesHealth Optimizing Physical Education: Learning Activity Sheet (LAS) Quarter 4John Wilfred PegranNo ratings yet

- User Manual LCD Signature Pad Signotec SigmaDocument15 pagesUser Manual LCD Signature Pad Signotec SigmaGael OmgbaNo ratings yet

- MF-QA-001 PDIR ReportDocument2 pagesMF-QA-001 PDIR ReportBHUSHAN BAGULNo ratings yet

- MB0042-MBA-1st Sem 2011 Assignment Managerial EconomicsDocument11 pagesMB0042-MBA-1st Sem 2011 Assignment Managerial EconomicsAli Asharaf Khan100% (3)

- Surface Coating ProcessesDocument7 pagesSurface Coating ProcessesSailabala ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- E.bs 3rd-Unit 22Document46 pagesE.bs 3rd-Unit 22DUONG LE THI THUYNo ratings yet

- 1651 EE-ES-2019-1015-R0 Load Flow PQ Capability (ENG)Document62 pages1651 EE-ES-2019-1015-R0 Load Flow PQ Capability (ENG)Alfonso GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Gregory University Library Assignment on Qualities of a Reader Service LibrarianDocument7 pagesGregory University Library Assignment on Qualities of a Reader Service LibrarianEnyiogu AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Recent Developments in Ultrasonic NDT Modelling in CIVADocument7 pagesRecent Developments in Ultrasonic NDT Modelling in CIVAcal2_uniNo ratings yet

- S4 - SD - HOTS in Practice - EnglishDocument65 pagesS4 - SD - HOTS in Practice - EnglishIries DanoNo ratings yet

- Science Web 2014Document40 pagesScience Web 2014Saif Shahriar0% (1)

- Strategy 13 Presentation - Social Emotional LearningDocument29 pagesStrategy 13 Presentation - Social Emotional Learningapi-588940234No ratings yet

- Italian Painters 02 MoreDocument450 pagesItalian Painters 02 Moregkavvadias2010No ratings yet

- The Diary of Anne Frank PacketDocument24 pagesThe Diary of Anne Frank Packetcnakazaki1957No ratings yet

- 6470b0e5f337ed00180c05a4 - ## - Atomic Structure - DPP-01 (Of Lec-03) - Arjuna NEET 2024Document3 pages6470b0e5f337ed00180c05a4 - ## - Atomic Structure - DPP-01 (Of Lec-03) - Arjuna NEET 2024Lalit SinghNo ratings yet

- Types of Stress: Turdalieva Daria HL 2-19 ADocument9 pagesTypes of Stress: Turdalieva Daria HL 2-19 ADaria TurdalievaNo ratings yet

- The Secret Language of AttractionDocument278 pagesThe Secret Language of Attractionsandrojairdhonre89% (93)