Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Price Transmission Notions and Components and The

Uploaded by

YaronBabaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Price Transmission Notions and Components and The

Uploaded by

YaronBabaCopyright:

Available Formats

Price transmission notions and components and the impact of food policies

Price transmission notions and components and the impact of food policies

Given prices for a commodity in two spatially separated markets p1t and p2t, the Law of One Price and the Enke-Samuelson-Takayama-Judge model postulate that at all points of time, allowing for transfer costs c, for transporting the commodity from market 1 to market 2, the relationship between the prices is as follows: p1t = p2t + c (1) If a relationship between two prices, such as (1), holds, the markets can be said to be integrated. However, this extreme case may be unlikely to occur, especially in the short run. At the other end of the spectrum, if the joint distribution of two prices were found to be completely

independent, then one might feel comfortable saying that there is no market integration and no price transmission. In general, spatial arbitrage is expected to ensure that prices of a commodity will differ by an amount that is at most equal to the transfer costs with the relationship between the prices being identified as the following inequality: p2t - p1t c (2)

Fackler and Goodwin (2001) refer to the above relationship as the spatial arbitrage condition and postulate that it identifies a weak form of the Law of One Price, the strong form being characterized by equality (1). They also emphasize that relationship (2) represents an equilibrium condition. Observed prices may diverge from relationship (1), but spatial arbitrage will cause the difference between the two prices to move towards the transfer cost. The spatial arbitrage condition implies that market integration lends itself to a cointegration interpretation with its presence being evaluated by means of cointegration tests. Cointegration can be thought of as the empirical counterpart of the theoretical notion of a long run equilibrium relationship. If two spatially separated price series are cointegrated, there is a tendency for them to co-move in the long run according to a linear relationship. In the short run, the prices may drift apart, as shocks in one market may not be instantaneously transmitted to other markets or due to delays in transport, however, arbitration opportunities ensure that these divergences from the underlying long run (equilibrium) relationship are transitory and not permanent.

The spatial arbitrage condition encompasses price relationships that lie between the two extreme cases of the strong form of the Law of One Price and the absence of market integration. Depending on market characteristics, or the distortions to which markets are subject, the two price series may behave in a plethora of ways, having quite complex relationships with prices

adjusting less than completely, or slowly rather than instantaneously and according to various dynamic structures or being related in a non linear manner. Given the wide range of ways prices may be related, the concept of price transmission can be thought of as being based on three notions, or components (Prakash, 1998; Balcombe and Morisson, 2002). These are:

co-movement and completeness of adjustment which implies that changes in prices in one market are fully transmitted to the other at all points of time;

dynamics and speed of adjustment which implies the process by, and rate at which, changes in prices in one market are filtered to the other market or levels; and,

asymmetry of response which implies that upward and downward movements in the price in one market are symmetrically or asymmetrically transmitted to the other. Both the extent of completeness and the speed of the adjustment can be asymmetric.

Within this context, complete price transmission between two spatially separated markets is defined as a situation where changes in one price are completely and instantaneously transmitted to the other price, as postulated by the Law of One Price presented by relationship (1). In this case, spatially separated markets are integrated. In addition, this definition implies that if price changes are not passed-through instantaneously, but after some time, price transmission is incomplete in the short run, but complete in the long run, as implied by the spatial arbitrage condition. The distinction between short run and long run price transmission is important and the speed by which prices adjust to their long run relationship is essential in understanding the extent to which markets are integrated in the short run. Changes in the price at one market may need some time to be transmitted to other markets for various reasons, such as policies, the number of stages in marketing and the corresponding contractual arrangements between economic agents,

storage and inventory holding, delays caused in transportation or processing, or "price-levelling" practices.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Pilot'S Operating Handbook: Robinson Helicopter CoDocument200 pagesPilot'S Operating Handbook: Robinson Helicopter CoJoseph BensonNo ratings yet

- VP Construction Real Estate Development in NY NJ Resume Edward CondolonDocument4 pagesVP Construction Real Estate Development in NY NJ Resume Edward CondolonEdwardCondolonNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Drill String DesignDocument118 pagesDrill String DesignMohamed Ahmed AlyNo ratings yet

- Preventing OOS DeficienciesDocument65 pagesPreventing OOS Deficienciesnsk79in@gmail.comNo ratings yet

- Cosntructing For InterviewDocument240 pagesCosntructing For InterviewYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Heat TreatmentsDocument14 pagesHeat Treatmentsravishankar100% (1)

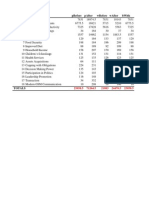

- No. Variables Pbefore Pafter Wbefore Wafter BwithDocument2 pagesNo. Variables Pbefore Pafter Wbefore Wafter BwithYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Tranform Roat EdDocument4 pagesTranform Roat EdYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Food Security Status in NigeriaDocument16 pagesFood Security Status in NigeriaYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- A Price Transmission Testing FrameworkDocument4 pagesA Price Transmission Testing FrameworkYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- OutputDocument1 pageOutputYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Out-Reach and Impact of TheDocument5 pagesOut-Reach and Impact of TheYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- SR - No. Investmentinputs Noimpact (0) P Littleimpact (1) P Greatimpact (2) P Totalproduct (P) %Document1 pageSR - No. Investmentinputs Noimpact (0) P Littleimpact (1) P Greatimpact (2) P Totalproduct (P) %YaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Analyses of Out-Reach and Impact of The Micro Credit SchemeDocument3 pagesAnalyses of Out-Reach and Impact of The Micro Credit SchemeYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Investments Capacity Pattern With Micro CreditDocument2 pagesInvestments Capacity Pattern With Micro CreditYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Micro Credit Impact On InvestmentsDocument2 pagesMicro Credit Impact On InvestmentsYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Adp 2013Document19 pagesAdp 2013YaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Frontier Functions: Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) & Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)Document45 pagesFrontier Functions: Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) & Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)YaronBaba100% (1)

- Questionnaire Management SurveyDocument15 pagesQuestionnaire Management SurveyYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Database Design: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 pagesDatabase Design: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Table Template For State Report2013Document19 pagesTable Template For State Report2013YaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Econometric Analysis UsingDocument13 pagesUnderstanding Econometric Analysis UsingYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Oppenheim-Questionnaire Design Interviewing and Attitude MeasurementDocument305 pagesOppenheim-Questionnaire Design Interviewing and Attitude MeasurementYaronBaba100% (1)

- QG To AIS 2017 PDFDocument135 pagesQG To AIS 2017 PDFMangoStarr Aibelle VegasNo ratings yet

- Algorithm - WikipediaDocument34 pagesAlgorithm - WikipediaGilbertNo ratings yet

- Effects of Organic Manures and Inorganic Fertilizer On Growth and Yield Performance of Radish (Raphanus Sativus L.) C.V. Japanese WhiteDocument5 pagesEffects of Organic Manures and Inorganic Fertilizer On Growth and Yield Performance of Radish (Raphanus Sativus L.) C.V. Japanese Whitepranjals8996No ratings yet

- STM Series Solar ControllerDocument2 pagesSTM Series Solar ControllerFaris KedirNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Report Zarin Tasnim Tazin 1920143 8Document6 pagesPortfolio Report Zarin Tasnim Tazin 1920143 8Fahad AlfiNo ratings yet

- CRC Implementation Code in CDocument14 pagesCRC Implementation Code in CAtul VermaNo ratings yet

- SC-Rape-Sole Testimony of Prosecutrix If Reliable, Is Sufficient For Conviction. 12.08.2021Document5 pagesSC-Rape-Sole Testimony of Prosecutrix If Reliable, Is Sufficient For Conviction. 12.08.2021Sanjeev kumarNo ratings yet

- SMK Techno ProjectDocument36 pagesSMK Techno Projectpraburaj619No ratings yet

- Elliot WaveDocument11 pagesElliot WavevikramNo ratings yet

- Starkville Dispatch Eedition 12-9-18Document28 pagesStarkville Dispatch Eedition 12-9-18The DispatchNo ratings yet

- Scope: Provisional Method - 1994 © 1984 TAPPIDocument3 pagesScope: Provisional Method - 1994 © 1984 TAPPIМаркус СилваNo ratings yet

- Nisha Rough DraftDocument50 pagesNisha Rough DraftbharthanNo ratings yet

- IEEE Conference Template ExampleDocument14 pagesIEEE Conference Template ExampleEmilyNo ratings yet

- Dmta 20043 01en Omniscan SX UserDocument90 pagesDmta 20043 01en Omniscan SX UserwenhuaNo ratings yet

- ACM2002D (Display 20x2)Document12 pagesACM2002D (Display 20x2)Marcelo ArtolaNo ratings yet

- Milestone 9 For WebsiteDocument17 pagesMilestone 9 For Websiteapi-238992918No ratings yet

- Matrix of Consumer Agencies and Areas of Concern: Specific Concern Agency ConcernedDocument4 pagesMatrix of Consumer Agencies and Areas of Concern: Specific Concern Agency ConcernedAJ SantosNo ratings yet

- Data Book: Automotive TechnicalDocument1 pageData Book: Automotive TechnicalDima DovgheiNo ratings yet

- Case Notes All Cases Family II TermDocument20 pagesCase Notes All Cases Family II TermRishi Aneja100% (1)

- CH 2 Nature of ConflictDocument45 pagesCH 2 Nature of ConflictAbdullahAlNoman100% (2)

- 0063 - Proforma Accompanying The Application For Leave WITHOUT ALLOWANCE Is FORWARDED To GOVERNMEDocument4 pages0063 - Proforma Accompanying The Application For Leave WITHOUT ALLOWANCE Is FORWARDED To GOVERNMESreedharanPN100% (4)

- Health, Safety & Environment: Refer NumberDocument2 pagesHealth, Safety & Environment: Refer NumbergilNo ratings yet

- Analisa RAB Dan INCOME Videotron TrenggalekDocument2 pagesAnalisa RAB Dan INCOME Videotron TrenggalekMohammad Bagus SaputroNo ratings yet

- Acevac Catalogue VCD - R3Document6 pagesAcevac Catalogue VCD - R3Santhosh KumarNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Management by John Ivancevich PDFDocument656 pagesHuman Resource Management by John Ivancevich PDFHaroldM.MagallanesNo ratings yet