Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Michigan Peremptory Orders: A Supreme Oddity

Uploaded by

WayneLawReviewCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Michigan Peremptory Orders: A Supreme Oddity

Uploaded by

WayneLawReviewCopyright:

Available Formats

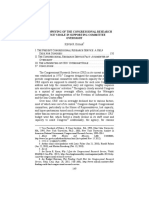

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS: A SUPREME ODDITY GARY M.

MAVEAL

I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 418 II. THE HISTORY OF THE PEREMPTORY ORDER RULE ........................... 420 A. Summary Decision Practices Before Modern Procedural Reform. .................................................... 422 1. Precursors of Peremptory Orders: Writs of Mandamus and Prohibition ........................................................................ 422 2. 1931-33 Rule Origins: Summary Writs on Applications ...... 424 B. The Reforms of the Revised Judicature Act and the 1963 Court Rules. .................................................................................... 428 1. The Studies for a Court of Appeals and Wholly Discretionary Supreme Court Review ...................................... 428 2. GCR 1963, 806.5 Authorization for Peremptory Orders in Emergencies ............................................................. 434 C. The Courts 1964 Rule for Summary Disposition on Any Application .............................................................................. 436 1. The 1963 Constitution: A Court of Appeals and Criminal Appeals as of Right ................................................... 436 2. The 1964 Emergency Amendments for Peremptory Order on any Application......................................................... 438 III. THE PREVALENCE OF PEREMPTORY ORDERS IN THE RECENT DECADES ................................................................................. 443 A. The Mid-1970s: Expanded Use of Peremptory Orders and Per Curiam Opinions ............................................................... 444 B. Increasingly Common Peremptory Rulings over Dissents ......... 452 IV. MICHIGANS PEREMPTORY RULE AND ORDERS UNIQUE AMONG THE STATES.............................................................................. 456

Professor of Law and Director of Faculty Research & Development, University of Detroit Mercy School of Law. B.A., 1977, Wayne State University; J.D., 1981, University of Detroit. I would like to thank Prof. Carol A. Parker, Associate Dean for Finance and Administration at the University of New Mexico School of Law, and Ann M. Byrne, of Bremer & Nelson LLP, in Grand Rapids, for their insights upon reviewing an early draft of this article. Their suggestions were invaluable. I also had the able contributions of student research assistants on this project over the past four years: Melissa Stamkos (J.D./LL.B. 2010), now of the New York Bar, Alia Nassar (J.D. 2011, now of the Michigan bar), and my current assistant, Laura Gibson, who will graduate this academic year.

417

418

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

V. CRITIQUE - MICHIGANS RULE AND PRACTICES ARE UNWARRANTED DEPARTURES FROM NORMS FOR STATE SUPREME COURTS ................................................................................. 464 VI. CONCLUSION ................................................................................... 474 APPENDIX .............................................................................................. 475 I. INTRODUCTION Michigan Supreme Court Rule 7.302(H)(1) authorizes summary affirmance or reversal of the court of appeals upon an application for leave to appeal.1 The rule allows the justices to forego the custom of full briefing after granting leave before deciding questions presented to it.2 The frequent use of this peremptory order rule to resolve important legal issues on applications has proven controversial, especially in cases in which one or more of the justices dissent from the summary reversal or affirmance.3 In other states, high courts rarely reach the merits of a question presented in passing on an application for leave to appeal.4 The prevailing custom elsewhere is for the supreme court to vote first on the application for review; if granted, full briefing, oral arguments, and deliberation inform subsequent decision on the merits.5 The preliminary inquiry of whether to hear a case is a critical aspect of judicial administration: is the question presented significant enough to warrant the expense and delay of a second appeal? This core screening function demands a supreme court to use selectivity and restraint in exercising the power of discretionary review. Our supreme court followed this practice throughout most of the twentieth century.6 If the court granted an application for leave to appeal, the parties fully briefed the question presented.7 This deliberative custom was tempered by allowing expedited rulings in cases of emergency or where a partys right to immediate relief is clear, e.g., as in mandamus.8 In 1964, in anticipation of the opening of the Michigan Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court crafted a rule that it might summarily affirm

1. MICH. SUP. CT. R. 7.302(H)(1) (2010). 2. Id. 3. See infra note 358 and accompanying text. 4. See, e.g., People v. Strohl, 458 N.E.2d 1305 (Ill. 1984); In re Sean X, 473 N.E.2d 40 (N.Y. Ct. App. 1984). 5. See material appended to this Article. 6. See infra Part II.A. 7. See infra note 70 and accompanying text. 8. See infra note 81 and accompanying text.

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

419

or reverse any decision of that new court after a review of an application for leave to appealeven when no emergency existed.9 As will be seen, Michigans 1964 peremptory order rule melded rules drawn for mandamus and emergency cases into a blanket authorization to rule summarily on the merits of any application to review the new court of appeals.10 This Article traces the history of the peremptory order rule change and its use since it was enacted. Part II reports the origin and evolution of the current rule, MCR 7.302(H)(1), to the former practice of summary grant of writs of mandamus.11 It reviews the study that informed both the Revised Judicature Act of 1961 and the General Court Rules of 1963.12 That report surveyed practices in the states with and without intermediate courts of appeals as well as our own Supreme Courts work.13 It raised a central concern that Michigans Supreme Court was overburdened with applications for leave to appeal and that it was trying to do too much in reviewing them with limited resources.14 The reports chief recommendations were use of court commissioners and establishing a court of appeals.15 Examining the role and structure of an intermediate court, the study concluded that its success hinged on that new court being the principal court for correcting errors.16 It warned that double appealsreview of rulings of a new court of appealswere a serious hazard and that the delay and expense of successive review could only be justified when needed to settle important questions of state law or to correct a miscarriage of justice.17 Disregarding this study and advice, the supreme court engineered rule changes in 1964 authorizing peremptory rulings on any applicationeven when no emergency existed.18 Part III details how the peremptory order rule has been transformed into a power to summarily rule upon any application.19 It documents the courts acknowledgment of more aggressive use of the power beginning in 1976.20 Under their internal policy adopted in 1983, the justices agreed

9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. See infra Part II.C. See infra Part II.C. See generally infra Part II. See generally infra Part II. See infra note 90 and accompanying text. See generally infra Part II.B.1. See generally infra Part II.B.1. See generally infra Part II.B.1. See generally infra Part II.B.1. See generally infra Part II.C.2. Infra Part III. Infra Part III.

420

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

that five votes (of their seven) were required to issue a peremptory order.21 The court changed the policy in 2003 to effectively allow a simple majority of four to summarily enter final decisions on applications.22 In practice, the court frequently used the peremptory order to summarily affirm or reverse judgments of the court of appeals by perfunctory order over objections of other justices.23 This Part also reviews the implementation of mini-oral arguments on applications, which often serve as a prelude to peremptory orders.24 Part IV surveys rules and practices of other states with intermediate courts of appeal. The Michigan Supreme Courts power to issue summary rulings on applications in run-of-the-mill cases is unique.25 Unlike Michigan, nearly all states rules provide only for granting or denying review of applications for leave to appeal.26 Michigan is the only high court in the United States that regularly disposes of requests for a discretionary appeal in non-emergency cases by ruling on the merits of the question presented.27 Part V is a critique of the courts rule and practices under it.28 It argues that they are extreme departures from the norms of state supreme courts and reflect poorly on the court. It concludes with a recommendation that the supreme court review its practices under M.C.R. 7.302(H)(1), invite the bars input and, at a minimum, (1) amend the rule to refer to such orders as summary, rather than peremptory and (2) restrict their use to cases presenting bona fide emergencies or where the Justices unanimously support summary disposition.29 II. THE HISTORY OF THE PEREMPTORY ORDER RULE The Michigan Supreme Courts current rule on disposition of applications, MCR 7.302(H)(1), authorizes entry of a final decision or a peremptory order: The Court may grant or deny the application, enter a final decision, or issue a peremptory order. There is no oral argument on applications unless ordered by the Court. The clerk shall issue

21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. See infra note 233 and accompanying text. See infra note 258 and accompanying text. Infra Part III.B. Infra Part III.B. See infra Part IV. See infra note 265and accompanying text. See generally infra Part IV. See infra Part V. MICH. SUP. CT. R. 7.302(H)(1) (2010).

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

421

the order entered and mail copies to the parties and to the Court of Appeals clerk.30 A typical peremptory order is a terse sentence of affirmance or reversal in lieu of granting the application; it does not specify the issues in the case or provide any reasoning.31 Peremptory dispositions are often referred to as back-of-the-book orders because they are found in the back pages of Michigan Reports. All orders on applications for leave to appealwhether grant, denial, or peremptory orderare published after opinions from the courts docket of calendar cases.32 Peremptory is an odd word to describe a high courts action on an application asking its permission for a discretionary appeal. The word connotes to laymen33 and lawyers34 a dismissive command cutting off debate as unwarranted or futile. Michigan is the only state to use the word in rules or statutes on discretionary appeals; most states rules recognize that grant or denial of an application affords a supreme court sufficient and prudent choices in most cases.35 The history of the peremptory order rule is somewhat tortuous, but its origins can be traced precisely to the Michigan Court Rules of 1931 and 1933 on emergency applications for leave to appeal.36 The drafters of the General Court Rules of 1963 carried forward similar provisions.37

30. Id. 31. The orders typically take the form of one-sentence statements resolving the issue without stating facts or detailing the precise issue presented. See Ann M. Byrne, Peremptorily Deciding State Constitutional Law Issues in Michigan: Cruel or Unusual Decision Making? 11 T.M. COOLEY L. REV. 213, 213 n.4 (1994) (critique of two such orders in criminal cases from 1993). 32. Beginning in 1971 with volume 383, each issue of Michigan Reports tallied the numbers of applications granted or denied in that portion of the term. See generally 383 Mich. 751 (1971) to 411 Mich. 751 (1981). While these statistics did not accurately capture all actions on applications, it is clear that the overwhelming majority of applications were granted or denied outright. Id. The practice of reporting the total number of applications granted or denied ended in 1981 with volume 411. Id. 33. The words common meanings are: 1. putting an end to all debate or action; 2. not allowing contradiction or refusal; imperative; 3. having the nature of or expressing a command; urgent; and 4. offensively self-assured; dictatorial. THE AMERICAN HERITAGE DICTIONARY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE, 1305 (4th ed. 2006). 34. The words legal definitions are equally dismissive: 1. final, absolute; conclusive; incontrovertible; 2. not requiring any shown cause; arbitrary. BLACKS LAW DICTIONARY 1251 (9th ed. 2009). 35. See e.g., ILL. S. CT. R. 315. 36. MICHIGAN COURT RULES ANNOTATED 122-24 (1931); KELLY S. SEARL, THE 1933 MICHIGAN COURT RULES ANNOTATED 387-91 (4th ed. 1933). 37. MICHIGAN GENERAL COURT RULES OF 1963 AND THE REVISED JUDICATURE ACT 1961 (1962).

422

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

Yet the supreme court appropriated a blanket peremptory power for all applications just before the court of appeals began operations in 1965.38 A. Summary Decision Practices Before Modern Procedural Reform 1. Precursors of Peremptory Orders: Writs of Mandamus and Prohibition Supreme court review in Michigan is strictly statutory, but was originally modeled on the English common law writ system.39 The customary means for reviewing a trial courts judgment at law was a writ of error from the high court.40 The writ of error issued upon a pleading to the supreme court in a second proceeding to examine a lower court record for legal error.41 The court long had jurisdiction to issue writs of error, habeas corpus, and the other original and remedial writs.42 Throughout most of the twentieth century, before Michigan established its court of appeals, review by our supreme court was nearly exclusively by discretionary application.43 Criminal defendants could not appeal their convictions as of right and parties to civil actions could do so only if the judgment exceeded $50044 or had invalidated a state law as unconstitutional.45 Rather than a right of appeal, the former practice invited review under the common law system. Writs of error and extraordinary writs were the primary means to review civil and criminal judgments or to challenge conduct by other public officials.46 In addition, bills of review

38. Infra Part II.B.2 39. Michigans Constitution has authorized the supreme court to issue writs of error since at least 1851. The history and function of the writ of error is discussed in Jones v. Eastern Michigan Motorbuses, 387 Mich. 619 (1939). 40. Id. 41. Id. 42. MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 600.217 (West 2012). The statute contains the essence of the language of the 1851 enactment on the supreme courts power to hear writs. 1851 Mich. Pub. Acts 106. 43. Maurice Kelman, Case Selection by the Michigan Supreme Court: The Numerology of Choice, 1992 DET. C. L. REV. 1, 2 (1992); Robert A. Kagan, The Evolution of State Supreme Courts, 76 MICH. L. REV. 961, 977-78 n.40 (1978). 44. 1917 Mich. Pub. Acts 347. See Kagan, supra note 43, at 978 (tracing changes in Michigan Supreme Courts mandatory appellate jurisdiction); Kelman, supra note 43, at 6-8 (detailing shameful twentieth century tradition of granting appeal as of right to losers of civil judgments of $501 while relegating those convicted of serious felonies to a wholly discretionary appeal). 45. 1923 Mich. Pub. Acts 247. 46. CITIZENS RESEARCH COUNCIL OF MICH., A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE MICHIGAN CONSTITUTION vii 8 (1961).

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

423

in equity and writs of certiorari, prohibition, and mandamus were customary means of obtaining supreme court jurisdiction.47 Certiorari was long employed in Michigan to review rulings of inferior courts and officers or boards exercising quasi-judicial functions.48 The writ of prohibition was used to check and remedy unauthorized practices by trial courts.49 Mandamus likewise commanded action of a lower court judge or other public official to act as required by law50 or accelerated review of patently erroneous judicial rulings where delayed appeal would frustrate a remedy.51 Mandamus was called a peremptory writ because it concluded the issue authoritatively; as a clear command to perform the duty or do the act indicated, no alternatives [were] given.52 Peremptory mandamus contrasted with alternative mandamus, that writ gave the respondent official the option of complying or showing cause to the court why he should not do so.53 Complaints in mandamus against public officials and agencies in both the supreme court and circuit courts were typically resolved summarily based upon pleadings and affidavits.54 The statute from 1915 authorized a show cause with four-days notice of a hearing to

47. See infra notes 48-51 and accompanying text. 48. Edson R. Sunderland, The Michigan Judicature Act of 1915, 14 MICH. L. REV. 383, 388 (1916). 49. Only the supreme court had power to issue writ of prohibition. MICH. COMP. LAWS 13446 (1915). 50. People ex rel Port Huron & Gratiot R.R. Co. v. Judge of St. Clair Circuit, 31 Mich. 456 (1875) (per curiam opinion on mandamus to command vacating ex parte appointment of corporate receiver). 51. See, e.g., Tawas & Bay Cty. R.R. Co. v. Circuit Judge for Iosco Cnty., 7 N.W. 65 (Mich. 1880) (issuing mandamus to vacate improper injunction; appeal as legal remedy inadequate due to delay in procedure); Dillon v. Shiawassee Circuit Judge, 91 N.W. 1029 (Mich. 1902) (issuing mandamus to vacate contempt citation against husband in divorce action). 52. CHESTER J. ANTIEAU, THE PRACTICE OF EXTRAORDINARY REMEDIES: HABEAS CORPUS AND THE OTHER COMMON LAW WRITS, 2.52 (1987); see also Woodford v. Hull, 7 S.E. 450, 451 (W. Va. 1888) (Mandamus lies to enforce the performance of ministerial duties . . . the awarding of the peremptory writ ends the proceeding). 53. See Harris v. State, 34 S.W. 1017, 1022-23 (Tenn. 1895). 54. For published opinions by circuit judges on mandamus applications a century ago, see Samuels v. Couzens, No. 76093, reprinted in 4 BI-MONTHLY L. REV. 27 (1920-21) (Wayne County Circuit Court, J. Jayne) (jewelers entitlement to business license); Stearns v. Vincent, No. 430, reprinted in 10 BI-MONTHLY L. REV. 158 (1926-27) (Jackson County Circuit Court, J. Dingeman) (addressing justice of the peaces mandamus claim for payment of compensation for trying criminal cases).

424

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

resolve any contested facts.55 If the circuit court denied the writ, application for supreme court review was available by certiorari.56 Mandamus was available against public agencies in the supreme court as a matter of original jurisdiction.57 It was also regularly sought in the supreme court against trial judges to challenge a variety of rulings, typically after trial.58 Modeling Englands Court of Kings Bench, Michigan (like other states) adopted these writs in assigning its supreme court with general supervisory control of public administrators.59 The prerogative writs played an important role in the development of responsible government throughout the United States.60 As will be seen, the supreme courts current peremptory order rule authorizes an analogous summary procedurenot limited to cases presenting clear-cut entitlement to relief. 2. 1931-33 Rule Origins: Summary Writs Upon Applications a. Emergency Applications for Leave to Appeal 1931 Rule 67: If either party claims that a case is of such a character as to entitle him to an early hearing, such as appeals [on] writs of mandamus, he may file for an early hearing.

55. MICH. COMP. LAWS 15184 (1915). 56. Woolman Constr. Co. v. Sampson, 188 N.W. 420, 421 (Mich. 1922) (action to compel four county drain commissioners to make payments to contractor); Jackson v. Vedder, 187 N.W. 702, 702 (Mich. 1922) (action by City of Jackson against its clerk to resolve election dispute concerning authorization to issue bonds); Letourneau v. Davidson, 188 N.W. 462, 465 (Mich. 1922) (certiorari to Industrial Accident Board); Carvey v. W. D. Young & Co., 188 N.W. 392, 392 (Mich. 1922) (certiorari to Department of Labor and Industry). 57. See generally Common Council v. Deland, 189 N.W. 35 (Mich. 1922). 58. For cases of review of a trial judges ruling in mandamus, see Miley v. Grand Traverse Circuit Judge, 186 N.W. 398, 399 (Mich. 1922); Christian v. Wayne Circuit Judge, 188 N.W. 359, 359 (Mich. 1922); Wackenhut v. Washtenaw Circuit Judge, 188 N.W. 352, 359 (Mich. 1922); Flowers v. Wayne Circuit Judge, 188 N.W. 411, 411 (Mich. 1922). 59. Leonard S. Goodman, Mandamus in the Colonies: The Rise of the Superintending Power of American Courts, 2 AM. J. OF LEGAL HIST. 1, 34 (1958) (In every well constituted government the highest judicial authority must necessarily have this supervisory capacity to compel inferior or subordinate tribunals, magistrates, and all others exercising public powers, to perform their duty.). 60. See generally Harold Weintraub, Mandamus and Certiorari in New York from the Revolution to 1880: A Chapter in Legal History, 32 FORDHAM L. REV. 681 (1964); Harold Weintraub, English Origins of Judicial Review by Prerogative Writ: Certiorari and Mandamus, 9 N. Y. L. F. 478 (1963).

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS ***

425

1933 Rule 60, 4: On showing of emergency, immediate consideration of the application may be prayed 1933 Rule 60, 5: Upon such application, the court, in lieu of leave to appeal may, in its discretion, order issuance of the proper original writ. In 1931, rules of appellate practice were first codified to treat mandamus and other writs in the same way as most discretionary appeals.61 The Michigan Supreme Court has had the power to establish and simplify general rules of practice since the Constitution of 1850.62 The court also had the power to prescribe rules on which appeals would be by right or by leave.63 In 1927, serious work on comprehensive court rules began.64 The legislature commissioned the Judicial Council of Michigan to make reports on continuous study of the organization, rules, and methods of procedure and practice of the states judicial system.65 University of Michigan Law School Professor Edson Sunderland led the drafting of rules for law and chancery cases to eliminate the myriad forms of common law pleading and simplify procedural statutes.66 The 1931 rules were designed to simplify appeals.67 Parties seeking review of lower courts and tribunals were to pursue appeal by filing a

61. Edson R. Sunderland, The New Michigan Court Rules, 29 MICH. L. REV. 586, 595 (1931) 62. A History of Michigan Court Rules up to 1945 by Justice North of Supreme Court appears in JASON L. HONIGMAN, MICHIGAN COURT RULES ANNOTATED, atv. (1949). 63. MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 600.232 (West 1961). As mentioned previously, neither criminal defendants nor aggrieved parties to a civil judgment less than $500.00 had a right to appeal in 1931. See supra, note 44. 64. 1927 Mich. Pub. Acts 900. See also Charles W. Joiner, Rules of Practice and Procedure: A Study of Judicial Rule Making, 55 MICH. L. REV. 623, 639-40 (1957); Charles W. Joiner, The Judicial System of Michigan, 38 U. DET. L. J. 505, 521 (1961). 65. 1929 Mich. Pub. Acts 106, was quoted in preamble to the councils third report to the governor, June 26, 1933. The council was chaired by a supreme court justice and included a circuit judge, three members of the bar, the attorney general, and one member of the faculty of the law school of the University of Michigan. Id. That U.M. faculty member, Prof. Edson Sunderland, was the laboring oar on the Judicial Council in preparing the Michigan Court Rules of 1931 and 1933. Id. 66. See generally Sunderland, supra note 61; J. Honigman, Edson R. Sunderlands Role in Michigan Procedure, 58 MICH. L. REV. 13, 16 (1959) (detailing Sunderlands work as secretary of the statutory commission to revise the rules of practice and procedure in state courts). 67. Sunderland, supra note 61, at 595.

426

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

notice to appeal, rather than by complaint with the supreme court.68 Under the Michigan Court Rules of 1931, parties seeking mandamus or other discretionary writ had to seek leave to appeal.69 Rule 60 prescribed disposition of the application: the supreme court would endorse them as either allowed or denied; if allowed, briefing of the questions would follow as a matter of course.70 If an emergency presented, Rule 67 allowed a party to urge an early hearing on the appeal, and it specified mandamus as a typical case warranting such expediting.71 The court rules were amended in 1933 with their most important changes on appellate procedure.72 The revised Rule 60 required applicants for leave to appeal to the supreme court to specify whether they sought review by general appeal or by prerogative writ, i.e., mandamus, prohibition, or certiorari.73 This new requirement was the reason for adding language to the Rule authorizing something other than simply granting or denying the application. If extraordinary writ was sought and deemed appropriate on the submitted papers, the court had power in lieu of leave to appeal, to simply issue the proper original

68. See MICH. CT. R. 55 (1931). The new rules for appeals effectively replaced fourteen different general means (and thirty other special provisions) of review under common law and statutes. Honigman, supra note 66, at 18. 69. Rule 60, Section 3 provided: Leave to appeal shall be required . . . : (1) Where such leave is expressly required by statute or rule. (2) Where the right of review sought to be exercised is statutory and is conferred only by certiorari, mandamus or other discretionary writ. (3) Where there is no statutory right to review, and certiorari at common law would be the appropriate remedy. (4) Where, in an action at law submitted on the facts to the court or jury, a judgment is rendered for the defendant, unless the trial judge shall certify that the controversy actually involves more than $500.00. MICH. CT. R. 60 (West 1931). 70. Rule 60, Section 2 provided in relevant part: The court to which application is made . . . shall thereupon endorse upon such application Allowed or Denied. MICH. CT. R. 60 (West 1931). 71. Rule 67 of the Michigan Court Rules of 1931 provided: If either party claims that a case pending in the supreme court is of such a character as to entitle him to an early hearing, such as appeals from orders allowing or refusing writs of mandamus, or cases which on any lawful ground ought to be heard without delay, he may at any time after the printed record is filed in the reviewing court, file a motion in said court for an order setting the case down for an early hearing, stating specifically the grounds or reasons upon which he bases his claim for such early hearing, and supporting his application with such citation of authorities and such affidavits as he may deem necessary. MICH. CT. R. 67 (WEST 1931) (emphasis added). 72. SEARL, supra note 36, at iii. 73. Id. at 387. Rule 60, Section 2(a) - Leave to Appeal to the Supreme Court provided in relevant part: [t]he application shall further state whether general appeal or appeal in the nature of mandamus, certiorari, prohibition, etc. is sought. Id.

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

427

writ.74 This summary procedure reflected the substantive standards for mandamus or prohibition: a clear showing that respondent had disregarded a duty to perform or refrain from performing an act justified prompt issuance of the writ.75 Mandamus and prohibition afforded a speedy remedy to enforce citizens rights against their government.76 Rule 60 of the 1933 Rules thus authorized that the application for leave to appeal be granted, denied, or, alternatively, that the proper original writ issue if such were appropriate.77 Under the Rule, applications seeking to appeal criminal or civil judgments were either granted78 or denied.79 If granted, they were then briefed as part of the courts plenary docket.80 If the case was an emergency, the court gave expedited consideration and issued a prompt decree of mandamus or prohibition.81 Honigmans treatise on the rules confirms that Rule 60s allowance for summary issuance of the proper original writ referred to appeals in the nature of mandamus or prohibition, over which the

74. Id. at 389. The new Rule 60, Section 5 provided: Upon such application the court, in lieu of leave to appeal, may, in its discretion, order issuance of the proper original writ. Id.; KELLY S. SEARLE, 3 A TREATISE ON PLEADING AND PRACTICE AT LAW AND IN EQUITY IN THE STATE OF MICHIGAN 1411 (1934). 75. Elec. Park Amusement Co. v. Murphy, 119 N.W. 1095 (Mich. 1909) (citing numerous Michigan cases in refusing writ of mandamus to compel trial judge to vacate order appointing trustee). 76. Twp. of Roscommon Cnty. v. Bd. of Supervisors, 13 N.W. 814, 815 (Mich. 1882). 77. SEARL, supra note 36, at 387, 389. MICH. CT. R. 60 5. The rule also allowed the appellant to seek emergency consideration that could be determined by the court, or a Justice thereof. See MICH. CT. R. 60 4, 7 (emergency ex parte motion for immediate consideration) (single justice). 78. In re Milners Estate, 36 N.W.2d 914, 916 (Mich. 1949). 79. Kirn v. Ioor, 253 N.W. 318, 320 (Mich. 1934) (denial of application for leave to appeal with concurrence of eight Supreme Court justices). 80. See Sunderland, supra note 61, at 595. 81. See, e.g., Streat v. Vermilya, 255 N.W. 604 (Mich. 1934) (application for leave to appeal from order enjoining election in Flint). Upon granting of motion for immediate consideration, the court directed issuance of mandamus to city clerk to conduct election. Id. See also Second Natl Bank & Trust Co. v. Reid, 8 N.W.2d 104 (Mich. 1943) (prohibition and mandamus to circuit judge to dismiss litigation under res judicata); In Jett v. Judge of Recorders Court, 114 N.W.2d 504 (Mich. 1962), in which the criminal accused complained of trial judges pretrial order referring him to a sanity commission, the supreme court treated an emergency application for leave to appeal as an original application for peremptory writ of mandamus and, upon review of the record, its peremptory order stayed the referral. Training the bar to channel complaints for extraordinary writs to applications for leave to appeal instead proved to be a challenging task. Honigmans treatise on the rules suggested that the court would exercise its appellate powers more freely than its powers by way of original proceedings. Honigman, supra note 62, at 598.

428

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

supreme court had original jurisdiction.82 The court clearly had power over such matters independent of general appellate jurisdiction or a grant of discretionary leave to appeal.83 Rule 60 was carried forward unchanged in all essential aspects with the adoption of the Michigan Court Rules of 1945.84 Finally, the 1933 Rules required the court to give notice of new rules and amendments.85 To conclude on the supreme courts practice before our court of appeals, summary decisions on applications for leave to appeal were limited to cases of mandamus, prohibition, or superintending control. While the courts docket of applications for leave to appeal was a significant part of its workload well before 1965, the Justices options under the rules were to grant or deny them.86 The 1950s brought significant growth in the courts workload and thoughtful study on how to handle it. B. The Reforms of the Revised Judicature Act and the 1963 Court Rules 1. The Studies for a Court of Appeals and Wholly Discretionary Supreme Court Review Professor Sunderland, and state bar committees he served on, had examined the idea of creating an intermediate court of appeals for Michigan since at least 1922.87

82. Honigman, supra note 62, at 598. In discussing Section 5, the annotations include several cases confirming the courts practice under the rule to issue such writs rather than granting the application for leave to appeal. Id. at 601-02 (citing Kirn, 36 N.W.2d at 914); see also Fellinger v. Wayne Circuit Judge, 21 N.W.2d 133 (Mich. 1946); Swanson v. Doty, 33 N.W. 2d 110 (Mich. 1948). 83. See MICH. COMP. LAWS 13535 (1929). See also MICH. COMP. LAWS 15184 (1929) (compilers notes to mandamus); MICH. COMP. LAWS 15193 (1929) (compilers notes to prohibition). Id. 84. See Honigman, supra note 62, at 596-604 (reproducing the 1945 Rules with annotations and commentary to Rule 60). 85. SEARL, supra note 36, at 519 (Rule 81). Rule 81 required that proposed new rules be furnished by the supreme court clerks to county clerks for conspicuous posting. Id. The goal was to enlist the bench, the bar, and the general public in commenting on such proposals for at least thirty days. Id. 86. MICH. STATE COURT ADMIN. OFFICE, REPORT OF THE STATE COURT ADMINISTRATOR 8 (1969) (describing justices individual work on applications prior to the summer of 1964, whereby they would recommend grant or denial to their colleagues). 87. See Edson R. Sunderland, Methods for Relieving Courts of Last Resort from the Growing Burden of Appeals, 1 MICH. ST. B. J. at cxxxiv (1921) (Report of the Committee on Legislation and Law Reform); Edward A. Macdonald, et al., Report of the Special Committee on Intermediate Appellate Courts, 10 MICH. ST. B. J. 43 (1930). Both reports examined the idea of dividing the supreme court into two or more divisions, an idea

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

429

In 1933, Professor Sunderland was the chief author of a lengthy report for the Judicial Council examining the ideal structure for an appellate system.88 The Organization and Operation of Courts of Review studied all aspects of appellate procedure in the state courts.89 Comparing practices and statistics, and drawing on the pertinent scholarship, it surveyed methods to improve both the capacity and efficiency of reviewing courts. Innovations in creating intermediate courts of appeals, adding lawyer staffing and deciding cases without opinions were all reviewed. Chief among its findings were the vexing aspects of double appeals in states with intermediate courts of appeal.90 The Sunderland report posited that allowing a discretionary second appeal undermines public confidence because non-lawyers could not understand how courts of substantially equal ability should reach different results on legal questions.91 It questioned double appeals in cases where a unanimous appeals court ruling was later reversed by a bare majority of a states supreme court as spectacle, decided by a minority of the combined number of all appellate judges, and gave illustrations of such a case as a cause clbre.92 It reviewed the practices of discretionary review in seven state supreme courts going back at least a decade and some cases to 1900.93 Reflecting on the merits of discretionary second appeals in other states, the Sunderland Report questioned their true benefit in light of their costs in time and expense.94 Delay in enforcing judgments typically deprives the first winner the use of their money or property.95 Might allowing such successive appeals effectively force winners of the first appeal to settle for a lower figure to avoid the delay of an application to a supreme court? Might systems allowing double appeals deter citizens from turning to the courts in the

which is also examined in a current treatise. ROBERT L. STERN, APPELLATE PRACTICE IN THE UNITED STATES, 50-57 (2d ed. 1981). 88. EDWARD O. CURRAN & EDSON R. SUNDERLAND, UNIV. OF MICH. LEGAL RESEARCH INST., THE ORGANIZATION AND OPERATION OF COURTS OF REVIEW: AN EXAMINATION OF THE VARIOUS METHODS EMPLOYED TO INCREASE THE OPERATING CAPACITY AND EFFICIENCY OF APPELLATE COURTS (1933) (Third Report of the Judicial Council of Michigan). 89. See id. 90. Id. at 186. 91. Id. 92. Id. at 186-87. 93. Id. The states cited in this section of the study included California, New York, and Pennsylvania. 94. CURRAN & SUNDERLAND, supra note 88, at 191. 95. Id.

430

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

first place? Sunderlands Report concluded these answers were unknowable, but were serious concerns.96 It appears that Sunderlands aversion to multiple appeals worked to delay serious consideration of an intermediate appellate court in Michigan. Before and after the 1933 Report, he published articles on the topic in journals urging state supreme courts to sit in divisions instead.97 Dean Roscoe Pound agreed that avoiding double appeals was essential to improve appellate procedure in the state courts: that [a]s a general proposition, one appeal in one case ought to be enough.98 In 1956, a Joint Committee on Michigan Procedural Revision was formed among the bench, the Michigan State Bar, and the Michigan legislature.99 Charles W. Joiner chaired a statewide committee of three

96. Id. 97. Edson R. Sunderland, Intermediate Appellate Courts, 14 J. AM. JUDICATURE SOCY 54, 55-56 (1930) (Advantages of a Single Court of Review, Sitting in Divisions, Impressively Presented by Prof. Edson R. Sunderland); Edson R. Sunderland, Two Appeals are Unjustifiable, 18 J. AM. JUDICATURE SOCY 182 (1935); The Problem of Double Appeals, 17 J. AM JUDICATURE SOCY 116 (1933); Edson R. Sunderland, The Burden of Double Appeals under a System of Intermediate Appellate Courts, 7 OHIO ST. B. ASSN REP. 1 (1934); Edson R. Sunderland, The Problem of Appellate Review, 5 TEX. L. REV. 126, 134 (1927) (Double appeals are an economic waste and a menace to public confidence in the courts.). One of Sunderlands indictments read: It is quite obvious that as a means of administering justice, double appeals are seriously objectionable. In the first place they involve an economic waste of time, money and effort. The allowance of a second appeal is analogous to the granting of a new trial. Every observant lawyer is aware that the whole trend of modern procedure is toward the development of methods which will enable cases to be so prepared before trial, so presented at the trial, and so dealt with on review, that they will not have to be tried again. These are exactly the same reasons why cases should be so reviewed that they need not be reviewed again. Litigants cannot afford either the time or the expense of repeated appeals. The public cannot afford to maintain a judicial establishment for continually doing over again what ought to have been done well enough in the first place. In the second place double appeals discredit the judiciary. Public confidence in the courts is undermined by the spectacle of one appellate court reversing another, particularly when such reversals are by divided courts and the final decision may represent the opinion of the minority of the judges who passed upon the case. In the third place, double appeals introduce a gambling element into litigation, which discourages resort to the courts and thereby impairs their usefulness as instruments of government. Edson Sunderland, The Problem of Double Appeals. 12 Tex. L. Rev. 47, at 49-50 (1933). 98. ROSCOE POUND, APPELLATE PROCEDURE IN CIVIL CASES, 327, 392 (1941) ([D]ouble appeals are to be avoided as far as possible.). See ROBERT A. LEFLAR, INTERNAL OPERATING PROCEDURES OF APPELLATE COURTS, 9-10 (1976) (One appeal is enough, but one should be allowed in almost any case.). 99. See COURT ADMIN. TO THE JUSTICES, ANNUAL REPORT AND JUDICIAL STATISTICS FOR 1956, 5-6 (1957) (announcing project).

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

431

dozen lawyers and judges (including three supreme court justices) to study a comprehensive reorganization to eliminate needlessly duplicative statutes.100 Jason L. Honigman also chaired the State Bar Committee on Civil Procedure that collaborated on that Joint Committees work.101 The work spanned nearly four years and progress reports were published as part of the courts annuals reports from 1956-60.102 The Joint Committees ambitious rewrite of rules of pleading and practice covered the gamut of modern reforms.103 On appeals, and at the request of the chief justice, the Committee also examined the courts decisional practices on applications for leave to appeal, compared them to practices in others states, and studied the desirability of an intermediate appellate court. 104 A major theme of the Joint Committees study was that the supreme court was overworked and that applications for leave to appeal were one of the very real burdens on the justices.105 The report reviewed the justices preparation of summaries and recommended dispositions to be

100. The Revised Judicature Act (RJA) eliminated some 1400 statutory provisions by combining them or incorporating them into the new court rules. JASON L. HONIGMAN, REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON CIVIL PROCEDURE, reprinted in the SUPREME COURT ADMINISTRATORS ANNUAL REPORT AND JUDICIAL STATISTICS 1961, 47, 49 (1961). 101. Id. 102. See COURT ADMIN. TO THE JUSTICES, supra note 99, at 5-6 (announcing project); JASON L. HONIGMAN, REPORT OF THE CIVIL PROCEDURE COMMITTEE OF THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE, ANNUAL REPORT AND JUDICIAL STATISTICS FOR 1958, 45 (1958); CHARLES JOINER, THE REVISION OF MICHIGANS PROCEDURE: A JOINT EFFORT, ANNUAL REPORT AND JUDICIAL STATISTICS FOR 1958, 49 (1958); JASON L. HONIGMAN, REPORT OF THE CIVIL PROCEDURE COMMITTEE OF THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE OF MICHIGAN, ANNUAL REPORT AND JUDICIAL STATISTICS FOR 1959, 58-59 (1959) (indicating members of the supreme court had been actively working with the Civil Procedure Committee for four years and that reports on the RJA and new court rules were in the justices hands for their review); JOINT REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE, ANNUAL REPORT AND JUDICIAL STATISTICS FOR 1960, 40 (1960) (summarizing the scope of the final product and status of enactment of the RJA and tentative approval of the proposed rules by the court). 103. Body attachments in debt actions were eliminated, pretrial discovery was liberally expanded, and the rules on pleading and joinder were relaxed to more fully eliminate the procedural distinctions between law and equity. See the Joint Report of the Joint Committee on Michigan Procedural Revision and the Committee on Civil Procedure, 40, MICH. STATE B. J. 24, 68-71 (1961), which is also found in SUPREME COURT ADMINISTRATOR ANNUAL REPORT FOR JUDICIAL STATISTICS FOR 1960, at 40 (1960). The legislature endorsed the project as well and named seven members to serve as legislative members. See H.R. Con. Res., 45, 84th Cong. (1956), which is detailed in the FINAL REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON MICHIGAN PROCEDURAL REVISION, 7 n.3 (1960). 104. N. O. Stockmeyer Jr., Rx for the Certiorari Crisis: A More Professional Staff, 59 A.B.A. J. 846, 849 (1973). 105. CHARLES W. JOINER, JUDICIAL ADMINISTRATION AT THE APPELLATE LEVEL MICHIGAN 9 (1959).

432

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

considered by the entire court in conference.106 Like miscellaneous motions, applications for leave to appeal were referred to as window matters because they were typically stacked on the window sills in the justices conference room.107 The Joint Committee saw that hundreds of applications every year were imposing a very real burden on the court108 and that the volume of work necessarily prevented it from concentrating on systemic improvements to the administration of justice in Michigan.109 The Joint Committees Report revisited the findings of the 1933 Sunderland Report in light of the courts increasing workload. Recall that the court was obliged to hear appeals as of right in civil cases where the judgment exceeded $500.110 The Joint Committee concluded that it was past time for Michigan to establish an intermediate court of appeals.111 At the same time, it warned that failing to guard against double appeals would undermine the value of a new court.112 While the problem of double appeals is its most serious where a second appeal is a matter of right, the Joint Committee saw the danger in routine grant of discretionary review.113

106. Id. 107. Id. at 8-9. 108. Id. The work on these window matters was detailed as follows: [T]he motions and matters involving the courts discretionary jurisdiction have increased rapidly during the past several years and last year reached a height not exceeded in twenty-five years. It is becoming one of the very real burdens on the part of the justices, consuming a substantial amount of each judges time. . . . In 1956, for example, there were almost six hundred such matters presented to the court, or twice as many as cases docketed for formal hearing. *** At the present time motions or petitions are filed with the clerk of the court who enters them on a motion docket. The clerk delivers them to the justices in rotation, in time to permit them to be considered before the scheduled conference of the court . . . . The memoranda, after circulation in advance of conference, sometimes consist of very substantial briefs and careful analysis of complicated facts. The reports comprise a summary of the facts and the question of law and the judges conclusions thereon. Id. at 3-4, 8-11. 109. The report detailed the variety of motions and applications the supreme court handled in the preceding years, extraordinary writs, superintending control, and applications for leave, with statistics on the volume of work they presented for each justice. Id. 110. See Kelman, supra note 43, at 6 n.20 (citing report prepared by Professor Joiner for the delegates of the constitutional convention documenting that supreme court obligatory civil appeals comprised the bulk of its 250 opinions in 1956). 111. See JOINER, supra note 105. 112. Id. 113. Id. at 34.

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

433

The Committee concluded that the supreme court was trying to do the impossible in both (1) leading the administration of justice by authoritative interpretation of law and (2) correcting errors in individual cases.114 Its 1959 report recommended that a court of appeals be created to realize appeal as of right in both civil and criminal cases and to reduce the supreme courts size from eight to five members and its jurisdiction to by-leave only.115 The new court would be the principal arbiter for correcting a trial courts errors.116 The Joint Committees Report also concluded that a system of commissioners might be well-suited to perform this work to assist the court in its screening of cases for review.117 The Joint Committees proposed court rules contained no significant change in the procedure for applications for leave to appeal. Rule 80.6 carried forward the allowance in the former Rule 60 for emergency consideration of an application.118 If an appellant made a showing of the need for immediate consideration, even ex parte, the court in lieu of leave to appeal, could in its discretion issue the appropriate peremptory order.119 The committee comment to the proposed rule cited Rule 60 of

[S]imilar objections could be made to double appeals that occur in the exercise of discretionary review. However, the consideration of requests . . . should be fewer than at the time present time. Indeed, such a system might permit more careful consideration of those requests than is now possible due to the burdens of the court. Such discretionary review power would be exercised only in significant cases made necessary for reasons of supervisory control and the crystallization and development of the law[.] Id. 114. Id. at 44. 115. Id. at 44-47. The supreme court consisted of eight members since 1905. 1903 Mich. Pub. Acts 250. See JOINT COMM. ON MICH. PROCEDURAL REVISION, FINAL REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON MICHIGAN PROCEDURAL REVISION, PART I, COMMITTEE REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS, 40, n.73 (1959) (on file with author); see also Joint Committee on Michigan Procedural Revision, 39 MICH. ST. B. J. 22, 52, 55 (summarizing the Committee Report and Recommendations). Both sources identify a second report of the Committee, Judicial Administration at the Appellate Level Michigan. JOINER supra note 105; see also Jason L. Honigman, Procedure - 1963: A Summary of the New Court Rules and Revised Judicature Act, 41 MICH. ST. B. J. 12 (1962). 116. JOINT COMM. ON MICH. PROCEDURAL REVISION, supra note 115, at 35. (The court of appeals would become the court for the correction of errors). 117. Id. at 12-16. 118. See MICH. CT. R. 60 4 (1931). 119. JOINT COMM. ON MICH. PROCEDURAL REVISION, 2 FINAL REPORT: JOINT COMMITTEE ON MICHIGAN PROCEDURAL REVISION, PART 3, PROPOSED COURT RULES AND COMMENTS 290 (1959). Proposed Rule 80.6.4 provided: Emergency Appeal. On showing of emergency, of appellants due diligence, and of the character of injury to him through observance of the above practice on application for leave to appeal, application may be made on ex parte

434

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

the 1931 Rules as its source and nothing in the history suggests it intended major changes in procedure.120 The Joint Committee drafters also introduced orders for superintending control as a means for finally abrogating the extraordinary writs of certiorari, prohibition, and mandamus against judicial officers.121 In short, it is apparent that the former practice for writs of mandamus was the source of the word peremptory in Proposed Rule 80.6. The rules and commentary do not suggest the drafters looked to expand summary decisions on applications. Rather, the evidence suggests proposed rule 80.6 was meant for cases of mandamus against public offices to compel required conduct and similar emergency injunctions. 2. GCR 1963, 806.5 Authorization for Peremptory Orders in Emergencies In 1961, the legislature approved nearly all of the Joint Committees measures as the Revised Judicature Act (RJA) and the supreme court promulgated the General Court Rules (GCR 1963).122 GCR 1963, Rule 806, with minor changes, authorized peremptory order on application only in emergency:

statement of fact, showing of merit, and on proof of such notice to other parties as the circumstances permit, or excuse for lack of notice, an immediate consideration of the application may be prayed. Upon such application the court, in lieu of leave to appeal, may in its discretion issue the appropriate peremptory order. Id. (emphasis added). 120. Id. at 291. The rules and commentary do not suggest that the court was seeking new avenues for deciding cases summarily based upon the application. Rather, all of the evidence suggests the proposed rule 80.6 was meant for cases in the nature of mandamus against public officers to compel required conduct and similar emergency injunctions. Id. 121. Id. at 187. Proposed Rule 70.11.3 provided: The following writs are superseded and an order of superintending control shall be used in their place: (1) Certiorari; (2) Mandamus, when directed to an inferior tribunal or an officer thereof; and (3) Prohibition. Id. Superintending control is a term from the Michigan Constitution of 1908 granting the supreme court jurisdiction over interior courts. MICH. CONST. of 1908 art. VII, 4. An order to show cause procedure was authorized for complaints for superintending control in the supreme court. Proposed Rule 70.10.7(2). Id. 122. Revised Judicature Act of 1961, 1961 Mich. Pub. Acts 418. The RJA also modernized the states statutory approach to personal jurisdiction and venue. John Demeester, Comment, Venue and Jurisdiction Under the Revised Judicature Act and General Court Rules of 1963, 8 WAYNE L. REV. 527 (1962); Jason L. Honigman, Procedural Changes in Michigan, 31 FED. RULES DECISIONS 113 (1962), Honigman, supra note 115, at 12; Robert Meisenholder, The New Michigan Pre-Trial Procedural Rules: Models for Other States?, 61 MICH. L .REV. 1389 (1963).

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

435

Emergency Appeal. On showing of emergency, of appellants due diligence, and of the character of injury to him through observance of the above practice on application for leave to appeal, . . . an immediate consideration of the application may be prayed. Upon such application the court, in lieu of leave to appeal, may in its discretion issue the appropriate peremptory order.123 Accordingly, if an applicant showed good grounds for immediate consideration, the court, in lieu of leave to appeal, could issue the appropriate peremptory order.124 The renumbering of proposed rule, and numerous changes not relevant here, confirm the supreme court scrutinized the proposed rules.125 The court also adopted the rules on extraordinary writs in a separate chapter.126 With the Joint Committees re-ordering ratified by the court, the RJA and the General Court Rules would be effective January 1, 1963.127 The adopted rules included procedures for amending them. GCR 1963, 933 required reasonable notice to the State Bar and its committees for comments, except in cases where the supreme court found a need for immediate action.128 Mr. Honigman reported that enlisting the bar and Judicial Conference was a significant innovation129 that would change

123. GCR 1963 806.5 provided in full: Emergency Appeal. On showing of emergency, of appellants due diligence, and of the character of injury to him through observance of the above practice on application for leave to appeal, application may be made on ex parte statement of fact, showing of merit, and on proof of such notice to other parties as the circumstances permit, or excuse for lack of notice, an immediate consideration of the application may be prayed. Upon such application the court, in lieu of leave to appeal, may in its discretion issue the appropriate peremptory order. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 806.5 (1962) (on file with author). 124. Id. 125. Papers of Charles W. Joiner, Memorandum from Supreme Court Reporter Hiram Bond to the Justices upon Re-Read of the Proposed Court Rules (November 1, 1961) (on file with the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library); Papers of Charles W. Joiner, Memorandum from Jason L. Honigman Approving the Courts Changes to the Rules (November 16, 1961) (on file with author). 126. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 710-718 (1962) (covering superintending control, habeas corpus, mandamus, quo warranto, and injunctions). 127. MICHIGAN GENERAL COURT RULES OF 1963 AND THE REVISED JUDICATURE ACT 1961 (1962). 128. Rule 933 also required the Supreme Court Administrator to notify relevant committees of the Judicial Conference. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 933 (1962). 129. HONIGMAN, supra note 100, at 49-50. (The Court has thus imposed restrictions on its own conduct as well as the circuit judges to guard against hasty or ill-conceived changes in procedural laws.).

436

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

previous practice on proposed rules.130 Though he noted the forthcoming court of appeals would necessitate new rules for appeals to the supreme court,131 Mr. Honigman could not have foreseen the justices would see the advent of the intermediate court as a reason to expand Rule 806.5 on emergency cases into an unlimited power of peremptory action on any application. C. The Courts 1964 Rule for Summary Disposition on Any Application The many changes of the RJA and the GCR were followed by the creation of the court of appeals in 1964. The supreme court used this as an emergency to adopt its peremptory order rule which continues as the basis for the current rule. As we will see, the court used Rule 933s authorization for emergency rule-making to radically expand its power to summarily act on applications. 1. The 1963 Constitution: A Court of Appeals and Criminal Appeals as of Right When Michigan convened its constitutional convention in April 1961, a key proposal was to create a court of appeals.132 As discussed earlier, the prospect of an intermediate court had been studied continually for at least seventy years133 before concrete proposals were

130. Honigman, supra note 115, at 28. 131. COMM. ON CIVIL PROCEDURE, REPORT OF COMMITTEE ON CIVIL PROCEDURE: ANNUAL REPORT AND JUDICIAL STATISTICS FOR 1961, 47, 50 (1961): Like all living organisms, the task of improvement of laws for the administration of justice can never be ended. Currently our state faces the prospect of adoption of a new constitution which provides for creation of an intermediate appellate court. Should this constitution be adopted, a new set of appellate rules will be needed as well as major changes in the practice and procedure of appeals to the Supreme Court. Id. 132. Delegates differed sharply on the value and wisdom of Art VI, 6, which required the supreme court to give written reasons for each decision, including those simply denying leave to appeal. See Ann E. Donnelly, An Analysis of Proposed Article VI and the State Bar Poll, 41 MICH. ST. B. J. 41, 43 (1962). Art. VI, 6 provides: Decisions of the supreme court, including all decisions on prerogative writs, shall be in writing and shall contain a concise statement of the facts and reasons for each decision and reasons for each denial of leave to appeal. When a judge dissents in whole or in part he shall give in writing the reasons for his dissent. MICH. CONST. art. VI, 6. See Ann E. Donnelly, An Analysis of Proposed Article VI and the State Bar Poll, 41 MICH. ST. B. J. 41, 43 (1962). 133. CURRAN & SUNDERLAND, supra note 88, at 202-04 (detailing Michigan state and local bar association reports consistently opposing the idea since 1892).

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

437

presented to the Constitutional Convention of 1961 and ratified by Michigan voters in April of 1963.134 The new court of appeals was to commence hearing cases on January 1, 1965 as the court of last resort for most litigants.135 As the tribunal for appeals of right in Michigans one court of justice, its decisions would be final, excepting for such review as prescribed by supreme court rule.136 The new constitution also gave criminal defendants an appeal as of right upon conviction.137 This new right would take effect March 1, 1964, but the new court of appeals would not be available to hear them until 1965.138 Substantial resources were invested into equipping the new court to serve as the primary appellate tribunal.139 While the supreme courts jurisdiction would become wholly discretionary in 1965, it was obliged to hear criminal appeals throughout 1964. Some legislators and judges voiced concerns that as the new court would not be operational by 1965, the supreme court might be overrun by criminal appeals.140 In January 1964, the urgent need to constitute the new court prompted the justices to issue an advisory opinion that the court of appeals judges had to be elected from districts drawn along county

134. The constitution was submitted at the election of April 1, 1963, and was adopted. A recount established the vote as 810,860 to 803,436. The effective date of the Constitution of 1963 was January 1, 1964. See MICH. CONST. 1963, Schedule 16. The background of the establishment of the Michigan Court of Appeals by the Constitution of 1963 has been well chronicled. Charles W. Joiner, The Judicial System of Michigan, 38 U. DET. L. J. 505, 529 (1961) (overview by Professor Joiner, who had served as Chairman of the Joint Committee on Procedural Revision since 1956). 135. CHARLES E. HARMON, A MATTER OF RIGHT A HISTORY OF THE MICHIGAN COURT OF APPEALS, 5 (2002). 136. 1964 Mich. Pub. Act 281 14 (codified at MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 600.314 (West 1964)). See MICH. CONST. art. VI, 1 (The judicial power of the state is vested exclusively in one court of justice which shall be divided into one supreme court, one court of appeals, one trial court . . .). See William J. Fleener Jr., Its a Dirty Job But Somebody Has to do it: Resolution of Conflicts and Law-Making in the Michigan Court of Appeals, 10 T. M. COOLEY L. REV. 149, 151-52, n.28 (1993) (quoting constitutional convention delegate Professor Harold Norris: [f]or many people this appellate court would be the court of last resort.). 137. MICH. CONST. art. I, 20. See Jensen v. Menominee Circuit Judge, 170 N.W.2d. 836 (Mich. 1969). The state bar had for many years recommended that a right to appeal be extended to criminal defendants. Carol A. Parker, Should the Michigan Supreme Court Adopt a Non-Majority Vote Rule for Granting Leave to Appeal?, 43 WAYNE L. REV. 345, 347 n.10 (1996) (citing Charles W. Joiner, The Judicial System of Michigan, 38 U. DET. L. J. 505, 529 (1961)). 138. See Parker, supra note 137. 139. See HARMON, supra note 135. 140. C. Rudow, Prod Legislature on Appeals Court, DETROIT NEWS, Jan. 19, 1964, at 13-B (naming state representatives and fact that unnamed [j]udges in Detroit and elsewhere have expressed alarm) (copy on file with author).

438

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

lines.141 The high courts sua sponte ruling drew praise from the Detroit Free Press.142 However, its editorial hoped the supreme court would fully deliberate matters before it after the new intermediate court was created.143 While the justices unsolicited advice to the legislature was welcomed given the public exigency, the Free Press cautioned the court not to forego appellate process regularly: In other cases, in which facts and arguments are developed in the lower courts, the long and slow trail is a better one. The Supreme Court needs to have everything at hand before it rules. With the discretion expected of it, we feel sure the Court will know the difference.144 Yet just a few days before the Free Press editorial, the court had given itself unlimited power to overrule virtually any court of appeals decision without the long and slow trail of briefing the merits of the legal question.145 2. The 1964 Emergency Amendments for Peremptory Order on any Application On January 21, 1964, with no notice to the bar under GCR 1963, Rule 933, the court signed amended Rule 806.7, that upon any application for leave to appeal, the court may, in lieu of leave to appeal, issue an appropriate peremptory order.146 The Rules broad expansion of the courts peremptory power to all applications was announced without any prior notice to the bar of the proposal.147 Ironically, the expedited rules operative wording of the hurriedly adopted rule was lifted directly from GCR 1963, 806.5,

141. See In re Court of Appeals, 125 N.W. 719, 719 (Mich. 1964) (explaining the supreme courts sua sponte directive, a letter to the governor and legislature on the meaning of the 1963 Constitutions provisions for imminently requisite election of court of appeals judges). 142. Editorial, Michigans High Court Eliminates a Detour, DETROIT FREE PRESS, Jan. 25, 1964 (copy on file with author). 143. Id. 144. Id. 145. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 806.7 was adopted on January 21, 1964. See infra Part II.C.2. 146. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 806.7 (emphasis added). Upon any application for leave to appeal, the court may, in lieu of leave to appeal, issue an appropriate peremptory order. Id. (adopted Jan. 21, 1964) (reprinted in Thomas M. Kavanagh, Supreme Court of Michigan, Resolution of Adoption, 43 MICH. ST. B. J. 34, 37 (1964)). 147. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 806.7, reprinted in 372 Mich. at xxiii. The courts resolution for the emergency rule change eliminated the notice requirements of GCR 1963, 933 because criminal defendants appeals as of right were already coming before it. MICH. CONST., art. I, 20. See Jensen, 170 N.W. 2d. at 836. The resolution provided that in cases of difficulty caused by the amendments, counsel might apply for solutional instructions. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 806.7, reprinted in 372 Mich. at xxiii.

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

439

allowing peremptory order only in emergencies.148 New rules also addressed the timing of criminal appeals to the supreme court before the court of appeals was operational.149 In particular, they set standards for granting leave to hear delayed appeals where appeal as of right had not been timely taken.150 It is unclear what motivated the court to give itself such an expansive peremptory order power. Concerns about delayed applications in criminal cases would seem to be the obvious explanation. There were no doubt concerns about the high number of criminal appeals coming before the supreme court, both by right and by delayed application for leave. Yet I found no record of the courts discussion of recasting GCR 1963, Rule 806.5 on emergency appeals to apply to all applications.151 The idea for such a rule was not identified by the justices on their agenda to address major policy questions posed by the coming court of appeals.152 The rules in all other state supreme courts authorized either granting or denying permission to review an intermediate courts judgment.153 As several justices were members of the Joint Committee and no doubt privy to its final report,154 it is surprising that they engineered such a drastic rule change without debate. The State Bar Committee on Civil Procedure, chaired by Professor Joiner and which included Mr. Honigman, complained in fall of 1964 about the courts adoption of rules in the preceding year without notice required by Rule 933.155

148. ROGER A. NEEDHAM, REVISED JUDICATURE ACT: SPECIAL PROCEEDINGS AND APPEALS 138 12.300 (1962 & Supp.1964 ) (copy on file with author). New Rule 806.7 was originally a part of the emergency appeal rule. Id. 149. See Jason L. Honigman, Appellate Practice 1965, 43 MICH. ST. B. J. 11, 12 (1964) (discussing resolution of adoption of amendments to GCR 1963, 518, 803, 803, and 807) (copy on file with author). 150. See MICH. GEN. CT. R. 803 (1963) (Time for Taking Appeal to the Supreme Court); MICH. GEN. CT. R. 806 (1963) (Appeals to Supreme Court By Right and By Leave) (adopted Jan. 21, 1964), reprinted in Kavanagh, supra note 146, at 37. 151. Professor Joiners voluminous papers on his intensive work (along with Mr. Honigman) on the rules during the period are conspicuously silent on this aspect of the 1964 rule changes. 152. See agenda of Major Policy Questions for the new court of appeals. Papers, Justice Otis Smith, Supreme Court Papers, Intermediate Court of Appeals 1963, Box 4, (on file at the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library) (on file with author). 153. See, e.g., ILL. S. CT. R. 302 (2012). 154. Professor Joiner mailed Justice Dethmers a copy of the Joint Committees Final Report on August 27, 1963. Letter from Professor to Justice Dethmers, Papers 19601966, Box 5 (on file with the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan), (copy on file with author). 155. See Report of the Committee on Civil Procedure, 43 MICH. ST. B. J. 27, 28 (1964) (The committee believes that the drafting of a number of the rules could been improved if the membership of the bar had been invited to comment . . . .).

440

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

However it came about, the new peremptory rule was a radical departure from prior rules and practices, as well as the recommendations of those who had studied other state courts. In addition to the State Bar Journal, the new rule on applications for leave to appeal was published in the Detroit Legal News.156 The front page notice reproduced the new rules in full, but tellingly printed in bold only the text of the new rule: 7. Upon any application for leave to appeal, the court may, in lieu of leave to appeal, issue an appropriate peremptory order.157 Later in 1964, the court again promulgated rules on an emergency basis for the new court of appeals and standards for granting of leave to appeal from its judgments.158 With the new court taking the Chapter 80 rules on appeals, the supreme court recast its peremptory order rule as Rule 853.159 Both sets of rules granted power of peremptory order on applications for leave to appeal to the new court of appeals and the supreme court.160 In drawing its own rules, Rule 853 provided that leave to appeal a judgment of the court of appeals would be allowed only if the matter was of major significance to the states jurisprudence, was clearly erroneous and would cause material injustice, or conflicted with another precedent or other court of appeals decisions.161 In summary, the new rules were professedly drawn to retain as much of the former practice as could be maintained in the face of changes requisite to the creation of the court of appeals.162 Yet they broke new ground in extending the power of summary decision beyond those seeking relief by extraordinary writ. The power of peremptory decision, including outright reversal, applied to all cases by amendments to GCR 1963, 852 (by-pass applications) and 853 (applications for leave to appeal).163 Rule 853.2(4) now provided Upon any application for leave to appeal, the court on its own motion or by stipulation of the

156. Supreme Court Rule 806.7, DETROIT LEGAL NEWS, Feb. 13 and 15, 1964, at 1. These front page notices did not include the Justices emergency resolution. 157. Id. (emphasis in original). 158. See MICH. GEN. CT. R. 806.7 (1963) (court of appeals); MICH. GEN. GT. R. 852.2(4)(g) (1963) (by-pass application to supreme court); MICH. GEN. CT. R. 853.2(4) (1963) (application for leave to the supreme court). 159. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 853.2(4). 160. Id. 161. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 853.1 (1963). In addition to the jurisdiction to review the court of appeals upon leave granted, the supreme courts rule permitted it to entertain emergency by-pass applications for leave to appeal prior to consideration by the intermediate court. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 852.1 (1963). 162. Honigman, Procedure 1963, supra note 115, at 12. Curiously, the Honigman Article does not mention the expansion of the peremptory order power. 163. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 852 (1963); MICH. GEN. CT. R. 853 (1963).

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

441

parties, may in lieu of leave to appeal enter a final decision or issue an appropriate peremptory order.164 As with the January 1964 rule, no rationale for Rule 853.2(4) appears in any reports on the proposed rules or other sources from the period.165 The rules primary authorization is for entry of a final decision on the application including affirmance, reversal, or remand to a lower court.166 An appropriate peremptory order no doubt referenced summary determination of what were formerly prerogative writs. This construction is confirmed by cases from 1964 and 1965, in which at least three of the justices used the term peremptory writs or orders in discussing mandamus.167 Michigans treatise on the General Court Rules confirmed for the bench and bar that peremptory orders were to be reserved for the rare case.168 The 1972 edition of the Honigman & Hawkins treatise explained the power would of course be used sparingly - only where it was clear that the matter was controlled by settled legal principles.169 The treatise cited only two cases: one granting mandamus to compel a scheduled election to proceed170 and another to review an injunction against a strike by public school teachers.171 Both cases involved bona fide emergencies; they were heard on applications to by-pass the court of appeals because of the clear need for prompt decision.172 Both rulings also took the form of per curiam opinions (not orders) setting forth their reasoning.173

164. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 853.2(4) (1963) (adopted Oct. 9, 1964), reprinted in Kavanagh, supra note 146, at 51). Rule 852.2(8), carrying a similar power for by-pass appeals was identical to Rule 853.2(4), except the word judgment was used in place of decision. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 852.2(8) (1963). The complete rules were set out as Chapter 80 of the General Court Rules of 1963 and were published in 373 Mich. xix-cxii. The rules were referred to by one author as hastily rewritten. See John J. Hensel, Appeals to the Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court, 63 MICH. B. J. 953 (1984). 165. I have reviewed the Bentley Historical Librarys extensive collection of papers of Professor Charles Joiner as well as collections of two supreme court justices who were on the court in 1964, Paul Adams and Otis Smith. 166. MICH. GEN. CT. R. 854.4 (1963). 167. See Superx Drugs Corp. v. State Bd. of Pharmacy, 125 N.W.2d 13, 21 (Mich. 1964); on rehg 134 N.W.2d 678, 681 (If it is, no peremptory writ or order should issue as a matter of policy (GCR 1963, 711.2)[.]). 168. 6 JASON L. HONIGMAN & CARL HAWKINS, MICHIGAN COURT RULES ANNOTATED 256 (2d Ed. West 1972). 169. Id. at 256 (Of course, such peremptory power will be exercise sparingly and only in those cases in which it is quite clear on the face of the application for leave to appeal that the disposition of the case will be controlled by settled legal principles.). 170. OBrien v. Detroit Election Commn, 179 N.W.2d 19 (Mich. 1970). 171. Crestwood Sch. Dist. v. Crestwood Educ. Assn., 170 N.W.2d 840 (Mich. 1969). 172. OBrien, 179 N.W.2d at 19; Crestwood Sch. Dist., 170 N.W.2d at 841. 173. OBrien, 179 N.W.2d at 19; Crestwood Sch. Dist., 170 N.W.2d at 841.

442

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 417

The Honigman & Hawkins commentary tempered the Rules expansive language for some years.174 A review of orders on applications from the late 1960s and early 1970s suggests that the court was restrained in using it.175 Peremptory rulings were issued only to expedite relief upon where the proper result was obvious (due to settled law or otherwise) or in emergencies.176 Peremptory orders accompanied grants of applications and were used to exercise supervisory powers, such as superintending control and mandamus, and to enforce procedural rights of the accused where the violation was apparent from the application.177 Occasionally the court would adopt the dissenting opinion in a published court of appeals decision as the appropriate summary disposition.178 Some cases saw sua sponte affirmance or reversal by the court immediately after it granted leavebefore briefing and argument.179 The orders often cited former G.C.R. 1963, 865.1(7), which authorized the

174. The 1977 edition of ICLEs manual on appellate practice did not even advert to peremptory decision except in the context of emergency applications and implied the courts options were to grant or deny applications. See generally JOHN J. HENSEL, APPEALS IN THE MICHIGAN COURTS (1977) (in particular, 13.05, et seq.). 175. Id. 176. One also finds a few cases during this period where no reference is made to the fact that the application for leave to appeal was being resolved summarily and no detail as to underlying trial court and unreported court of appeals rulings are given. See, e.g., Leinonen v. Houghton Circuit Judge, 384 Mich. 793 (1970) and Walli v. Houghton Circuit Judge, 384 Mich. 793 (1970) (separate applications with same attorneys for all parties summarily reversed trial court and dismissed cases); People v. Lorentzen, 384 Mich. 806, 806-07 (1971) (granting leave for defendant to appeal denial of bail bond pending appeal and ordering [t]he Oakland Country Circuit Court . . . to admit the defendant and appellant Eric Lorentzen to bail pending the determination of the appeal to this court.). 177. See, e.g., People v. Rolston, 291 N.W.2d 920 (Mich. 1974) (affirmance of double jeopardy dismissal); People v. Hopper, 381 Mich. 784 (1968) (pro se application granted and matter remanded to trial court for determination of indigency to warrant appointment of counsel); People v. Tanner, 199 N.W.2d 202 (Mich. 1972) (same grounds for grant and remand to Recorders Court for the City of Detroit); Collins v. Muskegon Circuit Judge, 384 Mich. 813 (1971) (remand to consider defendants belated appeal as of right to the court of appeals if it be shown that he had timely notified his lawyer of his desire to appeal his conviction). 178. See Travelers Indem. Co. v. Duffin, 184 N.W.2d 739, 740 (1971), revg, 184 N.W.2d 229 (Mich. Ct. App. 1970) (Decision of the Court of Appeals is reversed for the reasons given by Judge Levin in his dissenting opinion in that court, and the cause is remanded to the St. Clair County Circuit Court for jury trial within 30 days from the date of this order.). In Duffin, the trial judge had inappropriately denied the plaintiffs right to jury trial. Id. at 231-232 (Levin, J., dissenting). 179. See People v. Andriacci, 379 Mich. 791 (1967) (leave to appeal considered December 12, 1967. On its own motion, the Court directs that the Court of Appeals vacate its order of September 8, 1967. GCR 1963, 865.1(7)).

2012]

MICHIGAN PEREMPTORY ORDERS

443

court to issue all manner of miscellaneous relief at any time.180 (Rule 865 is subsumed into the current M.C.R. 7.316). In most cases, these summary rulings were without recorded dissents.181 In 1967, Professor Maurice Kelman noted the anomaly of peremptory orders reversing the court of appeals.182 He critiqued the supreme courts unexplained reversal in Williams v. Benson for failing to convey reasoning to the parties and the lower courts.183 In Williams, the intermediate courts published opinion wrestled with authorities from other state courts on the extent of a home-sellers obligation to disclose history of termite conditions.184 Professor Kelman wrote that the Justices had rejected out of hand . . . one of the most extensive opinions rendered to date by the immediate court. A sharper blow to the amourpropre of a court of appeals judge is unimaginable.185 The peremptory order rule was carried forward to the Michigan Court Rules of 1985 and remains in force as MCR 7.302(H)(1).186 III. THE PREVALENCE OF PEREMPTORY ORDERS IN THE RECENT DECADES After ten years of restraint in using the peremptory power from the 1964 rule changes, the court began regularly invoking it in cases where