Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vive Le Vol Bob Dylan and The Importance of Being Ernest Hemingway

Uploaded by

Francois GuillezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vive Le Vol Bob Dylan and The Importance of Being Ernest Hemingway

Uploaded by

Francois GuillezCopyright:

Available Formats

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

Goon Talk

"THE SCHEME IS FOR REAL"

search

JUL

21

Vive le Vol: Bob Dylan and the Importance of Being Ernest Hemingway

In 2006 poet and critic Stephen Scobie, author of Alias Bob Dylan, presented a paper titled "WHISKEY SAUCE: or, CHRONICLES: VOLUME TWO." In it he devotes a substantial chunk to exploring a "apparently simple or inconsequential" passage from Dylans Chronicles: Volume One. Scobie was right to be intrigued by the passage, but his analysis came up short, in that he missed a fascinating thing that Dylan does with the writing of Ernest Hemingway. The passage that captivated Scobie appears on page 170 of Chronicles: Volume One. It is the late 80's and Dylan writes about being in a creative slump and, "...exploiting whatever talent I had beyond the breaking point." On what he feels will be a breakthrough in his live performances he sustains an injury to his hand. He writes, "After being on the threshold of something bold, innovative and adventurous, I was now on the threshold of nothing, ruined." While waiting to see how and if his hand will heal he starts writing lyrics again. Then comes this: One day I went to the clinic where the doctor examined my hand, said the healing was coming along fine and that the feeling in the nerves might have a chance of coming back soon. It was encouraging to hear that. I returned to the house where my eldest son was sitting around in the kitchen with his soon-to-be-wife. There was a thick seafood stew brewing up on the stove as I walked by. I took the cover off the pot to check it out. What do you think? my future daughter-in-law asked. What about the whiskey sauce? It has to be arranged, she said. I dropped the cover back on the pot and went out to the garage. The rest of the day went by like a puff of wind. Here's a bit of Scobie's take: The passage begins in a matter-of-fact tone: I went to the clinic, the doctor said. When he records his feelings, he does so in an ironic understatement, so straight-faced as to be hilarious: told that his hand wound is healing, and that he may soon be able to play music again, all he says is It was encouraging to hear that. Then comes an anecdote about a seafood stew, foreshadowing the New Orleans setting later in the chapter. Bob as gourmet chef: tasting, advising. It all seems like a simple, almost banal incident: what is the point of including it in an autobiography? If there is a point, it seems to be contained in the answer by my future daughterin-law: It has to be arranged. But this proves to be a cryptic line. Is has to be being used as a loose future tense It has still to be arranged, but will beor in the stronger sense of a necessity It must be arranged? How exactly do you arrange a sauce? Should we take seriously the further sense of a musical arrangement, and see the line as looking forward to the main topic of the chapter, the recording of Oh Mercy: are Daniel Lanois arrangements the whiskey sauce for Dylans songs? As it turns out, we never do find out whether or not the sauce was added. The line is left hanging, and we turn to the simplicity of went out to the garage. Then Dylan caps the anecdote with a concise simile (the only overt image in this passage): The rest of the day went by like a puff of wind. It is on the one hand unrevealing: whatever happened between Dylan and his family, even whether the stew was any good or not, is not going to be told. But on the other hand, the image, simple as it is, opens up the whole

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 1 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

scene, explodes its limitations, nudges towards the universal. The image is simultaneously of the elemental and of the transient. (And thats not even to begin to consider the multiple echoes of wind in Dylans work.) Scobie makes some good points, but he misses the critical element. I suggest that what he did not recognize is that Dylan has telescoped an entire Ernest Hemingway short story, one that is apropos thematically, into those 135 words. I also suggest that Dylan lets the careful reader know of his intent to engage in this type of activity earlier in the book, through the use of passages from the same Hemingway short story. Scobie is right to recognize the foreshadowing of the New Orleans setting that comes a bit later in the book via the food that is discussed - the thick seafood stew and the whiskey sauce. I've demonstrated previously that a reference Dylan used to glean some images for that New Orleans section of the book is the travel guide New Orleans by Bethany Bultman. That is one of the things that is going on here as well. Here are two passages from the same page of Bultman's book. New Orleans, p. 226, "The tomato, when coupled with a roux, became an integral component in Shrimp Creole; the rich gravy for grillades; and the base for court bouillon (pronounced 'coo-bo-yon'), a thick seafood stew similar to bouillabaisse." New Orleans, p. 226, "Meatless gumbo z'herbes is eaten for Lent; bread pudding with whiskey sauce or pain perdu utilizes every last crumb of French bread; and what would the Christmas turkey be without oyster dressing, or breakfast without chicory cafe au lait?" Scobie states, "...we never do find out whether or not the sauce was added." No gourmet chef from New Orleans would ever add whiskey sauce to court bouillon, because it would be a flavor train wreck. Scobie may be no gastronome, but deserves credit for recognizing that thick seafood stew and whiskey sauce are New Orleans cuisine. This passage is the first use of material from Bultman's book in Chronicles: Volume One, and it is also the first time that he combines her writing with Hemingway's. In this case the two items also act as substitutes for elements from a Hemingway short story. In my essay "The Hidden Confederates in Bob Dylan's Attic" I presented an example from page 203 of Chronicles: Volume One that shows Dylan combining material from Bultman and Hemingway in the same sentence. On page 181 Dylan also combines elements from the two writers into one sentence - twice. Chronicles: Volume One, p. 181, "A place to come and hope you'll get smart - to feed pigeons looking for handouts." New Orleans, p. 85, "As the decades pass, Jackson Square the old town square that faces the river continues to be vitally alive with new generations of neighborhood children playing ball, lovers having a lunch-time smooch over a muffuletta, pigeons looking for handouts, and itinerant artists sketching the passersby." From "The Last Good Country" by Ernest Hemingway: "This time of year the Indians call them fool hens. After they've been hunted they get smart. They're not the real fool hens. Those never get smart. They're willow grouse. These are ruffed grouse. I hope we'll get smart, his sister said." Also on page 181 of Chronicles: Volume One comes this from Dylan, "Italianate, Gothic, Romanesque, Greek Revival standing in a long line in the rain." This sentence also contains both Bultman and Hemingway. New Orleans, p. 118, "These innovations allowed other decorative styles to flourish as well, particularly the Italianate, Gothic, and Romanesque." From "Cat in The Rain" by Ernest Hemingway, "The sea broke in a long line in the rain and slipped back down the beach to come up and break again in a long line in the rain." Perhaps to make sure that the use of Hemingway was not missed Dylan also includes other smatterings of Papa on the same page. Ill present two here; the most obvious lines. Chronicles: Volume One, p. 181, "There's only one day at a time here, then it's tonight and then tomorrow will be today again." From "The Last Good Country" by Ernest Hemingway, "He had already learned there was only one day at a time and that it was always the day you were in. It would be today until it was tonight and tomorrow would be today again." Chronicles: Volume One, p. 181, "Somebody puts something in front of you here and you might as well drink it." From "Out of Season" by Ernest Hemingway, "The young gentleman put one of the marsalas in front of her. 'You might as well drink it,' he said, 'maybe it'll make you feel better.'" Throughout Chronicles: Volume One lie numerous bits of Hemingway. An early one comes on page 60. Dylan lists a number of things that he spies in a room. He writes of, "...things to marvel overa little machine that put out four volts, a small Mohawk tape recorder, odd photos, one of Florence Nightingale with a pet owl on her shoulder, novelty postcardsa picture postcard from California with a palm tree." Then he states, "I'd never been to California. It seemed like it was the place of some special, glamorous race." Dylan is referencing a dig at F. Scott Fitzgerald from Hemingway's short story "The Snows of Kilimanjaro": He remembered poor Julian and his romantic awe of them and how he had started a story once that began, "The very rich are different from you and me." And how someone had said to Julian, "Yes they have more money. But that was not humorous to Julian. He thought they were a

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 2 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

special glamorous race and when he found they weren't it wrecked him just as much as any other thing that wrecked him. I suggest that the Mohawk tape recorder on Dylan's list is Hemingway's as well. Dylan uses material from the letters of a number of writers in Chronicles: Volume One, including Jack London and Thomas Wolfe. Here he turns to Hemingways letters. Dear Papa, Dear Hotch: The Correspondence of Ernest Hemingway and A.E. Hotchner, p. 269, "They would like you to speak onto one of your Mohawk tapes a sentence or two about THE KILLERS. Anything at all that can be used at the start of the show..." Dear Papa, Dear Hotch: The Correspondence of Ernest Hemingway and A.E. Hotchner, p. 270, "I cannot do the thing with the (Mohawk tape recorder) box as we got your letter yesterday + the box is in Malaga. If you really need something let me know..." The whiskey sauce passage appears in the Oh Mercy section of the book, and Dylan primes the reader for this passage by using Hemingway at least eleven times in the section before getting to that passage. Ill present two of the more obvious ones. Chronicles: Volume One, p. 151, "In the beginning all I could get out was a blood-choked coughing grunt and it blasted up from the bottom of my lower self, but it bypassed my brain." "The Short Happy Life of Frances Macomber" by Ernest Hemingway, "...his rifle cocked, they had just moved into the grass when Macomber heard the blood- choked coughing grunt, and saw the swishing rush in the grass." Chronicles: Volume One, p. 153, "I had a new faculty and it seemed to surpass all the other human requirements." "Fathers and Sons" by Ernest Hemingway, "Like all men with a faculty that surpasses human requirements, his father was very nervous." In "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" Harry has sustained an injury to his leg that has turned gangrenous while on safari in Africa. While waiting for help, which Harry is sure will not arrive in time, his wife urges him to keep his strength up. Harry knows that he is going to die and death visits him in a number of forms. Harry reflects on how he squandered his writing talent by selling out for an easy life among the rich. While on his death cot he muses on the stories that he did not write through a series of flashbacks. At one point in the story Harry wants to write and considers a way that he might be able to make it happen and has this exchange with his wife Helen: "You can't take dictation, can you?" "I never learned," she told him. "That's all right." There wasn't time, of course, although it seemed as though it telescoped so that you might put it all into one paragraph if you could get it right. On page 61 of Chronicles: Volume One (which just happens to be opposite the special, glamorous race lift) it is clear that Dylan is considering that passage when he writes: I needed to learn how to telescope things, ideas. Things were too big to see all at once, like all the books in the libraryeverything laying around on all the tables. You might be able to put it all into one paragraph or into one verse of a song if you could get it right. By doing this Dylan suggests a game plan; an intention to telescope "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" into one paragraph - if he can get it right. The first line on page 62 lays this out for the careful reader: '"Little things foreshadow what's coming, but you may not recognize them." Ill breakdown how Dylan telescopes the 10,000-plus words of "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" into a mere 135 words, and then Ill add some context to what Dylan is doing with the use of the Hemingway material by exploring how another writer did a similar thing with the story, even borrowing some of the same material. The Snows of Kilimanjaro is a story of death, but based on the context in which Dylan places his telescoped version death plays a secondary role. Dylan is primarily interested in Harrys thoughts on how he wasted his talent and the relationship between Harry and his wife Helen. Hemingway opens the story with, The marvelous thing is that its painless, he said. Thats how you know when it starts. We also learn that, Since the gangrene started in his right leg he had no pain and with the pain the horror had gone and all he felt now was a great tiredness and anger that this was the end of it as well as, He could stand pain as well as any man, until it went on too long, and wore him out, but here he had something that had hurt frightfully and just when he had felt it breaking him, the pain had stopped. Harry has no pain, no feeling in the nerves of his gangrenous leg. Dylan aligns with this by telling the reader, My hand had been gashed pretty good no feeling in the nerves. He asks, If my hand didn't heal, what was I going to do with the remainder of my days? A turning point for Dylan comes with, One day I went to the clinic where the doctor examined my hand, said the healing was coming along fine and that the feeling in the nerves might have a chance of coming back soon. Harry gets no such second chance. Helens hope for Harrys recovery and Harrys resignation that he is going to die play out in The Snows of Kilimanjaro through a series of scenes where she asks him to have some broth and he demands a whiskey-soda. You can go through the story with a highlighter and mark these sections if you want, but for convenience Ive telescoped these parts down into a playlet Ill call Broth and Whiskey-soda:

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 3 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

"I shot a T ommy ram," she told him. "He'll make you good broth and I'll have them mash some potatoes with the Klim. You ought to take some broth to keep your strength up." "Why don't you use your nose? I'm rotted half way up my thigh now. What the hell should I fool with broth for? Molo bring whiskey-soda." "Please take the broth," she said gently. The broth was too hot. He had to hold it in the cup until it cooled enough to take it and then he just got it down without gagging. "Wouldn't you like some more broth?" the woman asked him now. "No, thank you very much. It is awfully good." "Try just a little." "I would like a whiskey-soda." "It's not good for you." "No. It's bad for me. Cole Porter wrote the words and the music. This knowledge that you're going mad for me." "You know I like you to drink." "Oh yes. Only it's bad for me." "Molo!" he shouted. "Yes Bwana." "Bring whiskey-soda." "Yes Bwana." "You shouldn't," she said. "That's what I mean by giving up. It says it's bad for you. I know it's bad for you." "No," he said. "It's good for me. Should we have a drink? The sun is down." "Do you think you should?" "I'm having one." "We'll have one together. Molo, letti dui whiskey-soda!" she called. In The Snows of Kilimanjaro hope and resignation are represented by broth and whiskey-soda. If I were to telescope Broth and Whiskey-soda even more it would become a single exchange, with each item mentioned once. This is what Dylan does, although his version might be titled Thick Seafood Stew and Whiskey Sauce. Dylan substitutes Hemingways items for two similar items that he happened to find on the same page of Bultmans travel guide. By doing this he gets to play out these exchanges between Harry and Helen in a muted manner, while at the same foreshadowing his upcoming trip to New Orleans. Dylan also allows the careful reader the ability to track back to this passage by the repeated, and more obvious, combinations of Hemingway and Bultman that he throws at the reader later on. Dylan ends his 135 word scene with, The rest of the day went by like a puff of wind. Scobie asks the reader to, consider the multiple echoes of wind in Dylans work. If you start down that path, beginning with, Well, Bob Dylan wrote a song called Blowin In the Wind you will not get any closer to what is going on here. It is a dead end. The things to consider are the multiple echoes of the puff through the work of many writers. In The Snows of Kilimanjaro death comes in many forms, and one is a puff: This time there was no rush. It was a puff, as of a wind that makes a candle flicker and the flame go tall. When Dylan writes, The rest of the day went by like a puff of wind it is death that is echoing by. Dylan gives the reader an injury that no longer feels pain, hope and resignation in the form of the thick seafood stew and the whiskey sauce, and death in the form of a puff. He also places it in a broader context of the unattended, neglected muse. For Dylan it is Harrys realization that he didnt get the stories written that he should have, and his thoughts on what he can do in the face of his impending death, that are paramount. Harrys, "You can't take dictation, can you?" to Helen, and the unwritten stories that Harry presents in the telescoped flashbacks dovetails with what Dylan presents in that section of the book. Not sure that hell able to perform again in the wake of his devastating injury, he returns to writing, sketching out the lyrics for the songs that will fill his album Oh Mercy. Dylan avoids the sometimes fatal mistake of tacking on a happy ending to The Snows of Kilimanjaro by wrapping up the section with a paragraph that begins with, In time, my hand got right and it was ironic. I stopped writing the songs. William Burroughs wrote his own telescoped version of The Snows of Kilimanjaro and exploring this, as well as Burroughs thoughts on Hemingway and the use of the material of others, as well as how Dylan has used the material of Burroughs and how the material that both writers take from Hemingway overlaps adds useful context to what Dylan is doing in Chronicles: Volume One. A piece called "The Night Bob Came Round" by Raymond Foye appears in the book Wanted Man: In Search of Bob Dylan. Foye relates a 1985 encounter he had with Dylan at Allen Ginsberg's apartment. Harry Smith is staying with Ginsberg and Dylan wants to meet him, but Smith gives him the cold shoulder. Foye relates this exchange between Dylan and Ginsberg: "You still see Burroughs?" he asked. "I'm seeing him in Boulder next week," Allen responded. "T ell him... tell him I've been reading him," Dylan stammered. "And I believe every word he says." Empire Burlesque was released in June of 1985. Of course there was plenty of Burroughs material to read by that point, but The Adding Machine: Collected Essays had been released earlier that year. The book contains an essay on Hemingway, which touches on "The Snows of Kilimanjaro," and "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" also comes up in an essay on creative reading. In his review for Library Journal William Gargan complains that the collection is "occasionally marred by repetition," but when it comes to Burroughs that is completely missing the point. Burroughs was a raconteur who worked with his routines. He would riff on the same notion for decades, and he would recast similar material in a broad range of different contexts. Tracing the development on an idea, or use of a specific image, through his novels, short stories, lectures, films, classes, letters and essays is one of the great joys of studying Burroughs.

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 4 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

The Adding Machine includes an essay titled "Les Voleurs" (that's "The Thieves" if your French isn't up to snuff) in which he presents a manifesto he drew up with collaborator Brion Gysin that addresses an artist's right to use existing work. The manifesto includes, "Everything belongs to the inspired and dedicated thief" and ends with, "Vive le vol pure, shameless, total. We are not responsible. Steal anything in sight." Here's how Burroughs begins his essay: Writers work with words and voices just as painters work with colors; and where do these words and voices come from? Many sources: conversations heard and overheard, movies and radio broadcasts, newspapers, magazines, yes, and other writers; a phrase comes into the mind from an old western story in a pulp magazine read years ago, can't remember where or when: He looked at her, trying to read her mind but her eyes were old, unbluffed, unreadable." There's one that I lifted. The first essay in The Adding Machine is "The Name is Burroughs." In it appears this description of Salt Chunk Mary: "You eat first and then you talk business, your gear slopped out on the kitchen table, her eyes old, unbluffed, unreadable." And as you fall through Burroughs' writing this image appears again and again and again. From 1983's The Place of Dead Roads: "Now his eyes, old, unbluffed, unreadable, rest on Kim, as if tracing his outline in the air." From the 1965 piece "St. Louis Return," collected in The Burroughs File: "Bradly turned to face the question his eyes unbluffed unreadable two fingers in a vest pocket rested lightly on the cold blue steel of his Remington derringer." From 1962's The Ticket That Exploded: "eyes old unbluffed unreadable he hasn't said a direct word in ten years and as you hear what the party was like and what happened at lunch you will begin to see sharp and clear". From 1964's Nova Express: "I woke him up and he looked around with slow hydraulic control his eyes unbluffed unreadable". From 1979's Ah Pook is Here, and Other Texts : "There are three of them, little men in dark suits and gray felt hats, cold gray underworld eyes alert, unbluffed, unreadable in the yellow putty big city night faces." From a chapter written for 1981's Cities of the Red Night, but ultimately not included: "Noah Blake is a 15-year-old boy, eyes cold unbluffed unreadable, with a bevy of giggling replicas." For the initiated reader "unbluffed unreadable" appear as shorthand, a quick spell that brings forth a lineup of similar characters. Victor Bockris worked the image into an exchange between Burroughs and Mick Jagger captured in his piece "The Captain's Cocktail Party: Dinner with Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol and William Burroughs": JAGGER: Who did you shoot, Bill? [There was a static pause. Burroughs' eyes, unbluffed, unreadable, pinned on Jagger's face, looking a little surprised that Mick was not aware that he had accidentally shot his wife in Mexico in 1948.] BURROUGHS: It's a long story. It's a bad story. But I haven't shot anyone right lately. I assure you of that, Mick. I been on my good behavior. Bockris returns to the image in his 2003 book Keith Richards: The Biography: "As Keith's eyes unbluffed, unreadable, periscoped disdainfully towards the unfortunate Slash, Was could have sworn they turned an inhuman, radiating black." This type of thematic patterning abounds in the writing of Burroughs. Read through his work and keep an eye out for variations on "most distasteful thing I ever stood still for," for example. In a 1976 lecture on writing sources, one that includes some of the ideas that show up in "Les Voleurs," Burroughs asks a couple of key questions: An important point here is the misconception that a writer creates in a vacuum using only his very own words. Was he blind, deaf and illiterate from birth? A writer does not own words any more than a painter owns colors, so let's dispense with this originality fetish. Is a painter committing plagiarism if he paints a mountain or a landscape that other painters have painted? Narrowing the focus down to Burroughs' writing on, and use of, Hemingway, and specifically his interest in "The Snows of Kilimanjaro," yields some fascinating motifs. Burroughs devotes a lot of his writing to death; books of the dead, travel to the afterlife, mummification practices and the like. And it is death that draws Burroughs to the story. In his essay "Creative Reading" he writes: The Snows of Kilimanjaro was certainly the best if not the only writing Hemingway ever did. It is one of the best stories in the language about death, the stink of death. You know the writer has been there and brought it back. The end deserves a place among the great passages of English prose, with the end of Joyce's The Dead and the end of The Great Gatsby. The pilot was pointing: "White white white as far as the eye could see ahead, the snows of Kilimanjaro." And a blinding flash of white must have been the last thing Papa saw when he put the double-barrel 12gauge shotgun against his forehead and tripped both triggers. In his essay "Hemingway" Burroughs returns to this last line: He wrote his life and death so closely that he had to be stopped before he found out what he was doing and wrote about that. There is the moment when the bull looks speculatively from the cape to the matador. The bull is learning. The matador must kill him quick. Two plane crashes in a row, both near Kilimanjaro. The matador has to smash his head against the window of a burning plane. Otherwise he would have found out why two planes crashed near Kilimanjaro; he wrote it. He wrote it in The Snows of Kilimanjaro, where Death is the pilot. "He was pointing now, white white white as far as the eye can see ahead, the snows of Kilimanjaro." That's the last line. He who writes death as the pilot of a small plane in Africa should beware of small planes in Africa, especially in the vicinity of Kilimanjaro. But it was written, and he stepped right into his own writing.

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 5 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

Burroughs punctuates this with, "Fix yourself on that: 'White white white as far as the eye can see ahead . . . the snows of Kilimanjaro.'" Here Burroughs is also referencing the fix yourself on that/fix yourself on this dialogue from "The Gambler, the Nun, and the Radio," another short story that appears with The Snows of Kilimanjaro in the collections The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories and The Snows of Kilimanjaro and Other Stories. If you do fix yourself on the "white white white" passage you'll find that Burroughs uses it all the time. In a 1963 letter to Brion Gysin he writes, "The interesting possibility of beneficial (to me of course and my uh ravenous constituents) virus is still in the laboratory stage but Doc Benway tells me 'We are getting some darned interesting side by golly'. Think of it. Boys to the sky and each one look like other. Its Heaven, kid far as the eye can see ahead the snows of Kilimanjaro." In Exterminator! it takes the form of an atomic blast: At Hiroshima all was lost. The metal sickness dormant 30,000 years stirring now in the blood and bones and bleached flesh. He cut himself shaving looked around for styptic pencil couldn't find one dabbed at his face with a towel remembering the smell and taste of burning metal in the tarnished mirror a teen-aged face crisscrossed with scar tissue pale grey eyes that seemed to be looking at something far away and long ago white white white as far as the eye can see ahead a blinding flash of white the cabin reeks of exploded star white lies the long denial from Christ to Hiroshima white voices always denying excusing the endless white papers why we dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima how colonial peoples have benefited from our rule why look at all those schools and hospitals overgrown with weeds... In The Ticket That Exploded it takes the form of heroin death smell: It's the old junk gimmick ... to keep your ass in deep freeze Junk is not blue and it is not green Sex and pain forms hatching out in paralyzed flesh and hatching out hungry so you need more and more of the white stuff to keep your ass in deep freeze Junk is not blue and it is not green Junk is White White White like the colorless no-smell of death from kicking addicts From Nova Express: Let me tell you about a score of years' dust on the window that afternoon I watched the torn sky bend with the wind . . . white white white as far as the eye can see ahead a blinding flash of white . . . (The cabin reeks of exploded star). . . . Broken sky through my nostrils. In The Wild Boys: A Book of the Dead he combines the line with the white lies from the song "My Blue Heaven": "When evening is nigh . . . the dark city dying sun naked boy hugging his knees . . . I hurry to my . . . music across the golf course a crescent moon cuts the film sky . . . "blue heaven ... . . "The night that you told me . . . decent people know ... they are right . . . "those little white lies . . . White white white as far as the eye can see ahead a blinding flash of white fed up with Godless anarchy and corruption the cabin reeks of exploded stars. In The Soft Machine the line becomes about race, in the mouth of the District Supervisor of Trak News Agency. He says, "You can't deny your blood kid You're white white white And you can't walk out on Trak There's just no place to go." A version of the District Supervisors monologue kicks off the 1963 film Towers Open Fire, a collaboration between Burroughs and director Antony Balch. In a 1984 interview Brion Gysin misremembers the opening of the film in an intriguing way: C: In Towers Open Fire, there's that long monologue at the beginning about... BG: White, white, white, as well as the eye can see... Gysin is clearly thinking of Burroughs take on "The Snows of Kilimanjaro," something he'd been aware of for decades. Considering the fascination that Burroughs had with what happens on the passage through death it makes sense that the end of the Hemingway story would intrigue him. Harry clearly dies when Hemingway writes, "He could not speak to tell her to make it go away and it crouched now, heavier, so he could not breathe. And then, while they lifted the cot, suddenly it was all right and the weight went from his chest." In the next scene death visits one last time in the form of Compton the pilot, who takes Harry away. The scene, but not the story, ends with these two sentences: Then they began to climb and they were going to the East it seemed, and then it darkened and they were in a storm, the rain so thick it seemed like flying through a waterfall, and then they were out and Compie turned his head and grinned and pointed and there, ahead, all he could see, as wide as all the world, great, high, and unbelievably white in the sun, was the square top of Kilimanjaro. And then he knew that there was where he was going. It turns out that the line that Burroughs quotes so many times is as much of a phantom as Compton. "He was pointing now, white white white as far as the eye can see ahead, the snows of Kilimanjaro" is not the last line of the story it does not appear in the story at all. While it is possible that it is simply a matter of Burroughs misremembering the passage I think that a case can be made for Burroughs choosing to put those words into the pen of Hemingway. A 1970 letter to his son Billy shows Burroughs choosing to attribute a line to Hemingway: Writing is dangerous and few survive it, as Hemingway said or might have said. I can recommend Hemingway: A Life Story by Carlos Baker. I think its (sic) says a great deal about writing and what a writer is actually doing when he writes. Hemingway quite literally wrote his

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html

6 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

own death from The Snows of Kilimanjaro. A version of the quote that he attributes to Hemingway there shows up in The Western Lands, as Burroughs was never one to let a notion go without trying it out a couple of different ways. In a 1983 interview Burroughs comments on how, "...Hemingway sold out for a safari, and let them make a terrible movie out of 'The Snows of Kilimanjaro,' with a happy ending. A book about a story about death, with a happy ending!" In one of his lectures he comments: All these dumb kids, they don't know what a devil's bargain is. They said, Well, the story still remains The Snows of Kilimanjaro. I said, Yes, the story remains. But that's not the point. The point is what happens to the writer." The devil's bargain is the main theme in The Black Rider: The Casting of the Magic Bullets, a collaboration between Burroughs, director Robert Wilson and T om Waits. In the libretto Burroughs incorporates the tale of Hemingway allowing this change to his story, and in the production one could hear a recording of Burroughs saying, "He who hang happy ending on story about death, shall likewise take a hangman's rope." When discussing Hemingways suicide, the end result of this devils bargain according to Burroughs, he occasionally chooses to illustrate it by using a favorite passage from the Hemingway short story A Natural History of The Dead, one that is a bit over the top in its attempt at black humor. In a 1983 interview Burroughs says this: Let me see if I can quote it for you. T alking about someone dead in the book, lying in the trenches somewhere: "The hole in his forehead where the bullet went in was about the size of a pencil. The hole in the back of his head where the bullet came out was big enough to put your fist in, if it was a small fist and you wanted to put it there. [laughs] Oh boy... well, I reckon the hole in the back of his head where two barrels of number 6, heavy duck load came out was big enough to put your foot in, even if it was a medium-sized foot and you didn't want it there. No one could have written that but Papa Hemingway. I think his style killed him and, uh, he ended up blowing his head off. By that point Burroughs had been quoting and referring to that line for decades, even before Hemingways death. He begins a 1955 letter to Jack Kerouac with, I am now settled in my own house in the Native Quarter which is so close to Paul Bowles house I could lean out the window and spit on his roof if I was a long range spitter and I wanted to spit there. It shows up in a passage from 1971s The Wild Boys: A Book of the Dead: The General was still on his feet trying to massa the sneezes when a rifle bullet drilled him between the eyes. He flopped on his face and bounced. In the immortal words of Hemingway the hole in the back of his head where the bullet came out was big enough to put your fist in if it was a small fist and you wanted to put it there. In a 1973 letter to a woman threatening suicide and proposing marriage Burroughs writes: You should stop thinking about suicide and get on with your life and forget an unworkable illusion. I mean suppose as a young writer I had fallen in love with Djuna Barnes, the great Lesbian novelistHave you read Nightwood?...fallen in love sight unseen and with as little knowledge of her tastes, habits, past and present circumstances as you have of mine. Could that have worked out? Of course not. Homosexuality is an illusion and so is heterosexuality. So maybe I fall in love with Papa Hemingway. Super male writer goes gay at 60? He would have needed that like a hole in the head big enough to put a big fist in if he didnt want to put it there. All is illusion to be sure but some illusions function and some do not. In a 1989 interview Burroughs is showing off some firearms to an interviewer and says, Now this is a fine weapon. The hole where the bullet enters is about the size of a pencil. The one where it exits is big enough to stick your whole fist into, if you should care to stick your fist into such a place. In a journal entry dated June 29, 1997 Burroughs stages a battle between the two most atrocious conceits in the English tongue with Papa Hemingway in this corner. By this late date the quote is remembered as: The hole in his forehead where the bullet went in was the size of a pencil at the unsharpened end. The hole in the back of his head where the bullet went out was big enough to put your fist in [it], if it was a small fist, and you wanted to put it in there. In more than forty years of quoting the line it had transformed quite a bit. Theres as much Burroughs in it as there is Hemingway. Heres how the sentence appears in A Natural History of The Dead: This is where those writers are mistaken who write books called Generals Die in Bed, because this general died in a trench dug in snow, high in the mountains, wearing an Alpine hat with an eagle feather in it and a hole in front you couldn't put your little finger in and a hole in back you could put your fist in, if it were a small fist and you wanted to put it there, and much blood in the snow. This atrocious conceit is clearly one that he loved. In his essay Hemingway Burroughs writes about his own approach to writing dialogue, If you can look at a character without taking, from inner silence, then your character will talk, and you get some realistic

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html

7 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

dialogue. He goes on to write: But Hemingway didn't give his characters a chance to talk. He always talked for them, and they all talk Hemingway. T ake The Killers; it reads well, a good story, and very carefully assembled. The dialogue sounds good, but how good is it? He then goes to present the banter about the big dinner from the story, and a comparison with the original story shows that Burroughs is doing it from memory. Hes pretty close, but hes not exactly right. In this case as well his protestations did not stop him from using the line in his own work. From The Killers: What do they do here nights? Al Asked. They eat the dinner, his friend said. They all come here and eat the big dinner. From Cities of the Red Night: It's an exclusive-type place where everybody goes. What do people do in T amaghis? They see the Show. They all come here and see the big Show. There's a hanging show every night. The bar is filling up now, because this is Flasher Night. Dylan snatches the same Hemingway dialogue and uses it in Chronicles: Volume One: Some people were there from the art world, toopeople who knew and commented on what was going on in Amsterdam, Paris and Stockholm. One of them, Robyn Whitlaw, the outlaw artist, walked by in a motion like a slow dance. I said to her, What's happening? I'm here to eat the big dinner, she responded. In 1989 a small collection from Burroughs called Tornado Alley was published and it includes his own take on The Snows of Kilimanjaro, titled Where He Was Going. It is a brief tale, just over 1,000 words, and an examination reveals that, unlike his long held habit of recalling Hemingway from memory, he has returned to the original text and is carefully quoting from it. The white white white bit is absent. In an introduction to the story on a recording that appears on his 1990 album Dead City Radio Burroughs says, "This story from Tornado Alley, Where He Was Going, is, quite frankly, based on The Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway. In fact there are several quotations and Where He Was Going is a quotation." The title of his story lets the careful reader know that hes returned specifically to the passage that he had so long ago transfigured into the white, white, white line, and is considering it anew. While he certainly quotes very deliberately and exactly from the Hemingway story, the writer that Burroughs quotes most from in Where He Was Going is himself. Burroughs keeps the tale in the 1930s, but moves the location to the American Midwest. Bank robbers are holed up in a house and are preparing their escape. Ishmael is hit in a gunfight with the feds and dies on a stretcher. While dying he has a vision of traveling to Mexico City and meeting a young man on Dia De Los Muertos. Where He Was Going begins with the gangsters plotting their getaway. A similar scene, almost verbatim, appears in his novel The Western Lands. A passage about facing death is reworked from The Western Lands as well. From The Western Lands: If you face death all the time, for what time you have you are immortal. It was always like this, the sick hollow fear, when he feels as if he is fainting . . . then the rush of courage, the clean, sweet feeling of being born. He read that somewhere, about an Old West shootist and how he felt after a shootout. But the fear can go on and on until you can't stand it, it's going to break you, and that's when the fear breaks you hope. From Where He Was Going: Its always like this, he tells himself: the fear, and then a rush of courage and the clean sweet feeling of being born He read that somewhere, in an old western . . . but the fear can go on and on until you can't stand it, it's going to break you, and that's when the fear breaks you hope. Where He Was Going also includes, Ishmael remembers old Doc Benway saying, You face death all the time and for that time you are immortal. There are obviously ties in these passages to Burroughs writing on the use of the material of others, specifically the unbluffed, unreadable eyes remembered from an old western story in a pulp magazine presented earlier. Ishmaels death trip to Mexico City takes him through the city of Tamazunchale: He must have dozed off in the car. Another shoot-out dream. He knows they have been driving all night, home safe now, coming down into a valley. Warm wind and a smell of water. "Thomas and Charlie." "What?" "Name of this town." Ish remembers Thomas and Charlie. From here you climb ten thousand feet to the pass. Remembers Mexico City and his first grifa cigarette. The same scene appears just a few pages into Naked Lunch: . . . . Drove all night, came at dawn to a warm misty place, barking dogs and the sound of running water. "Thomas and Charlie," I said.

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html

8 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

"What?" "That's the name of this town. Sea level. We climb straight up from here ten thousand feet." I took a fix and went to sleep in the back seat. The boy that Ishmael encounters in Mexico City has white teeth, red gums, a smell of vanilla and a gardenia behind his ear. This is a stock figure in his writing; boys encountered in The Western Lands, Cities of the Red Night and the introduction to Queer share these same characteristics. Beyond the title the first use of Hemingway lines comes in this bit one that includes another echo of that puff: And suddenly it occurred to him that he was going to die. Not "sooner or later" he knew that of course, they all did but tonight. It came in a puff, like wind that makes a candle flicker, and sick, hollow fear hit him like a kick in the stomach. Burroughs has combined two appearances of death from The Snows of Kilimanjaro. Heres the first of them from Hemingway: Drinking together, with no pain now except the discomfort of lying in the one position, the boys lighting a fire, its shadow jumping on the tents, he could feel the return of acquiescence in this life of pleasant surrender. She was very good to him. He had been cruel and unjust in the afternoon. She was a fine woman, marvellous really. And just then it occurred to him that he was going to die. It came with a rush; not as a rush of water nor of wind; but of a sudden, evil-smelling emptiness and the odd thing was that the hyena slipped lightly along the edge of it. And the second: She looked at him with her well-known, well-loved face from Spur and Town & Country, only a little the worse for drink, only a little the worse for bed, but Town & Country never showed those good breasts and those useful thighs and those lightly small-of-back-caressing hands, and as he looked and saw her well-known pleasant smile, he felt death come again. This time there was no rush. It was a puff, as of a wind that makes a candle flicker and the flame go tall. A few paragraphs later Burroughs returns to this material, with the hyena becoming a raccoon, A raccoon crosses the road, its eyes bright green in the headlights, not hurrying, slipping along and it came with a rush, a sudden, evil-smelling emptiness and the raccoon was slipping lightly along the edge of it Later on Burroughs plays with the imagery more liberally. In The Snows of Kilimanjaro Harrys death trip with Compton in the Puss Moth is prefaced by the landing of the plane: It was morning and had been morning for some time and he heard the plane. It showed very tiny and then made a wide circle and the boys ran out and lit the fires, using kerosene, and piled on grass so there were two big smudges at each end of the level place and the morning breeze blew them toward the camp and the plane circled twice more, low this time, and then glided down and levelled off and landed smoothly The fires to help land the plane become fireworks in Where He Was Going: They stop to watch two pinwheels spinning in opposite directions . . . he remembers the queasy, floating feeling he got watching it, like being in a fast elevator. The boy is smiling now and pointing to the black space between the pinwheels as they sputter out and the blackness spreads wide as all the world and then he knew that was where he was going . . . . The long repeated white white white has become blackness, and Burroughs follows Hemingways wide as all the world, great, high, and unbelievably white in the sun, was the square top of Kilimanjaro. And then he knew that there was where he was going quite closely when compared to the numerous other examples presented earlier. Again, at just over 1,000 words the emphasis is on short in this short story from Burroughs, and he chooses to leave a lot out. Hes not interested in the relationship between Harry and his wife Helen, or Harrys internal struggle over wasting his talent. Im not suggesting that Dylan had considered what Burroughs had done with The Snows of Kilimanjaro when he came to work with it, but an examination of how the work of Burroughs appears in Dylans work around the time that Chronicles: Volume One was being written shows that Dylan was certainly considering the experimental writing techniques of Burroughs. In Dylans 2003 film Masked and Anonymous the viewer enters the Midas Judas Building on the way to Uncle Sweethearts office. A sign opposite the elevator lists the other tenants, and Dr. Benway has an office that is a floor below Sweethearts. Later in the film Uncle Sweetheart delivers this: Alexander the Great. Thats who Im talking about. He went out and raised an army, cooked all his enemies in crank case oil, rounded up all the wise citizens and doused them in canned heat, wiped his mouth, looked around, went home, went to bed, and died. Left every nation he plundered and conquered for his enemies to divide. Sure, he could have stayed home and strummed on his guitar, but you never would have heard of him. He never would have been

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html

9 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

Alexander the Great. The passage includes a series of elements lifted from the islam incorporated and the parties of interzone routine from Naked Lunch: Robert's brother Paul emerges from retirement in a local nut house and takes over the restaurant to dispense something he calls the Transcendental Cuisine... Imperceptibly the quality of the food declines until he is serving literal garbage, the clients being too intimidated by the reputation of Chez Robert to protest. SAMPLE MENU: The Clear Camel Piss Soup with boiled Earth Worms ____ The Filet of Sun-Ripened Sting Ray basted with Eau de Cologne and garnished with nettles ____ The After-Birth Supreme de Boeuf cooked in drained crank case oil, served with a piquant sauce of rotten egg yolks and crushed bed bugs ____ The Limburger Cheese sugar cured in diabetic urine, doused in Canned Heat Flamboyant... So the clients are quietly dying of botulism . . . Then A.J. returns with an entourage of Arab refugees from the Middle East. He takes one mouthful and screams: "Garbage God damn it! Cook this wise citizen in his own swill!" More material from Naked Lunch shows up in the script. Ella the Fortune T eller, while reading the palm of reporter T om Friend, states this: Your laziness stands in front of you and the life you've dreamed of. You're living in a nation that's dying a slow death. Look at the faces on your money. Slave owners and Indian fighters. They'll soon be replaced by the faces of strangers. Look at your sacred monuments and your tombs of heroes. They're being desecrated and upturned. Everything your nation has stood for. Every commitment, every truth, every ideal, everything of beauty, all these things are being stripped away. You are living in a world where all the jewels, diamonds, pearls, and rubies have been replaced by queer replicas. I see a lot of anger here, and you scoff at things you don't understand. Part of what she tells Friend is built from material that appears in the ordinary men and women routine in Naked Lunch: "So this elegant faggot comes to New York from Cunt Lick, T exas, and he is the most piss elegant fag of them all. He is taken up by old women of the type batten on young fags, toothless old predators too weak and too slow to run down other prey. Old moth-eaten tigress shit sure turn into a fag eater...So this citizen, being an arty and crafty fag, begins making costume jewelry and jewelry sets. Every rich old gash in Greater New York wants he should do her sets, and he is making money, 21, El Morocco, Stork, but no time for sex, and all the time worrying about his repHe begins playing the horses, supposed to be something manly about gambling God knows why, and he figures it will build him up to be seen at the track. Not many fags play the horses, and those that play lose more than the others, they are lousy gamblers plunge in a losing streak and hedge when they win...which being the pattern of their lives...Now every child knows there is one law of gambling: winning and losing come in streaks. Plunge when you win, fold when you lose. (I once knew a fag dip into the till -- not the whole two thousand at once on the nose, win or Sing Sing. Not our Gertie...Oh no a deuce at a time...) "So he loses and loses and lose some more. One day he is about to put a rock in a set when the obvious occur.'Of course, I'll replace it later.' Famous last words. So all that winter, one after the other, the diamonds, emeralds, pearls, rubies and star sapphires of the haut monde go in hock and replaced by queer replicas... Dylan has taken the writing of Burroughs and incorporated it into a divination scene. Burroughs thought that some of his techniques had powers of divination. In a recording titled Origin And Theory Of The T ape Cut-Ups that appears on the release Break Through in Grey Room he states, "When you experiment with cut-ups over a period of time you find that some of the cutups and rearranged texts seem to refer to future events" and goes on to suggest that, "when you cut into the present the future leaks out. While what both Burroughs and Dylan are doing with The Snows of Kilimanjaro in Where He Was Going and Chronicles: Volume One are not cut-ups it is worth taking a look at how both Dylan and Burroughs both point to the same influence when it comes to this experimental writing technique. This exchange appears in a 1966 interview with Burroughs that ran in The Paris Review: INTERVIEWER: How did you become interested in the cut-up technique?: BURROUGHS: A friend, Brion Gysin, an American poet and painter, who has lived in Europe for thirty years, was, as far as I know, the first to create cut-ups. His cut-up poem, Minutes to Go, was broadcast by the BBC and later published in a pamphlet. I was in Paris in the summer of 1960; this was after the publication there of Naked Lunch. I became interested in the possibilities of this technique, and I began experimenting myself. Of course, when you think of it,

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 10 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

The Waste Land was the first great cut-up collage, and Tristan Tzara had done a bit along the same lines. Dos Passos used the same idea in The Camera Eye sequences in U.S.A. I felt I had been working toward the same goal; thus it was a major revelation to me when I actually saw it being done. Dylan shows his appreciation and awareness of what Dos Passos was doing by taking a couple of the newspaper headlines that were incorporated in those sequences in U.S.A. and using them in a passage in Chronicles: Volume One, as Ive demonstrated in a previous essay. Ive heard criticism from very vocal sometimes a cigar is just a cigar types who suggest that one should just let the words and music of Bob Dylan flow over you, and only respond emotionally. I say that in Chronicles: Volume One a cigar is something that is used to suggest a different approachone that requires more active participation. In the "Oh Mercy" section the first song that Dylan writes about writing is "Political World." He finishes with these three sentences: From the far end of the kitchen a silver beam of moonlight pierced through the leaded panes of the window illuminating the table. The song seemed to hit the wall, and I stopped writing and swayed backwards in the chair, felt like lighting up a fine cigar and climbing into a warm bath. This was the first song I'd written in a while and it looked like a clawish hand had written it. He adds, I put the words in a drawer, couldn't play them anyway, and snapped out of a trance. By doing this Dylan seems to be referencing a classic argument when it comes to approaches to music writing and criticism. He draws attention to what he is doing by surrounding the key sentence with sentences that include bits taken from this passage of Sax Rohmers The Yellow Claw: A hand, of old ivory hue, a long, yellow, clawish hand, with part of a sinewy forearm, crept in from the black lobby through the study doorway and touched the electric switch! Eight!... The study was plunged in darkness! Uttering a sob a cry of agony and horror that came from her very soul the woman stood upright and turned to face toward the door, clutching the sheet of paper in one rigid hand. Through the leaded panes of the window above the writing-table swept a silvern beam of moonlight. Scobie wondered about that It has to be arranged line. I see much of Dylans book as being arranged. What we find between the two sentences that have the Sax Rohmer bits in that carefully arranged passage is, The song seemed to hit the wall, and I stopped writing and swayed backwards in the chair, felt like lighting up a fine cigar and climbing into a warm bath. German music critic Eduard Hanslick (1825 1904) argued for the active listener, one who listens to music with the intent of discovering the method of composition, over the passive listener, for whom music is merely sound to float in. In his 1854 book On the Musically Beautiful Hanslick positions his argument this way: Slouched dozing in their chairs, these enthusiasts allow themselves to brood and sway in response to the vibration of tones, instead of contemplating tones attentively. How the music swells louder and louder and dies away, how it jubilates or trembles, they transform into a nondescript state of awareness which they naively consider to be purely intellectual. These people make up the most appreciative audience and the one most likely to bring music into disrepute. The aesthetic criterion of intellectual pleasure is lost to them; for all they would know, a fine cigar or a piquant delicacy or a warm bath produces the same effect as a symphony. The similarities of the warm bath, fine cigar, the chair and the swaying are the signs that Dylan is again putting into play the I needed to learn how to telescope things, ideas notion that he got from Hemingway. Dylan makes his case for the aesthetic criterion of intellectual pleasure though analysis. He is not writing in a trance. He has, all the books in the libraryeverything laying around on all the tables. T o not recognize and explore these things can make you the one most likely to bring music into disrepute. That is a heavy burden to put on a reader or listener, but its what Dylan does. Dylan, through Hemingway, writes, You might be able to put it all into one paragraph or into one verse of a song if you could get it right. Ive shown how Dylan put an entire Hemingway short story into one paragraph. Could Dylan have done this in a song as well? He asks the reader to look. Love and Theft is an album of quotations. In Chronicles: Volume One Dylan uses a Hemingway quote that is about Fitzgerald, and Dylan quotes The Great Gatsby in the song Summer Days. If you start there and work out you dont have to go far to find more Hemingway. The verse that comes right before the one with the Gatsby quote is: Wedding bells ringin, the choir is beginning to sing Yes, the wedding bells are ringing and the choir is beginning to sing What looks good in the day, at night is another thing Jake Barnes is talking in that last line. Heres the final paragraph of the fourth chapter of The Sun Also Rises: We kissed again on the stairs and as I called for the cordon the concierge muttered something behind her door. I went back upstairs and from the open window watched Brett walking up the street to the big limousine drawn up to the curb under the arc-light. She got in and it started off. I turned around. On the table was an empty glass and a glass half-full of brandy and soda. I took them both out to the kitchen and poured the half-full glass down the sink. I turned off the gas in the dining-room, kicked off my slippers sitting on the bed, and got into bed. This was Brett, that I

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 11 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

had felt like crying about. Then I thought of her walking up the street and stepping into the car, as I had last seen her, and of course in a little while I felt like hell again. It is awfully easy to be hard-boiled about everything in the daytime, but at night it is another thing. Wedding bells do ring in The Sun Also Rises , but not for Jake of course. On the fishing trip Bill Gorton needles Jake; heres part of the exchange: As I went downstairs I heard Bill singing, Irony and Pity. When you're feeling . . . Oh, Give them Irony and Give them Pity. Oh, give them Irony. When they're feeling . . . Just a little irony. Just a little pity . . . He kept on singing until he came downstairs. The tune was: The Bells are Ringing for Me and my Gal. I was reading a week-old Spanish paper. The irony and pity routine also serves as a reference to Fitzgerald, much like the special, glamorous race line from The Snows of Kilimanjaro that Dylan incorporated into Chronicles: Volume One. In his biography Hemingway Kenneth Schuyler Lynn lays it out cleanly: The first of Bill and Jake's comic routines slyly pokes fun at The Great Gatsby by picking up on the words "irony and pity" and riding them hard. "Irony and pity" were Anatole France's touchstones for good writing, and the French-literature-loving Gilbert Seldes had invoked them in his Dial review of Gatsby. Fitzgerald, Seldes proclaimed, now surpassed all the writers of his generation; although he had taken only a tiny section of American life for his province, he had reported on it "with irony and pity and a consuming passion." Fitzgerald proudly showed these comments to Hemingway, who didn't like Seldes in any case because of what he regarded as his Harvard-bred intellectual snobbery and who probably didn't feel too good in addition about the lavishness of Seldes's praise of a rival. In A Moveable Feast he would dismiss the review with the sour remark that it "could not have been better. It could only have been better if Gilbert Seldes had been better." But in The Sun Also Rises he made it the occasion for a vaudeville turn, sung to the tune of "The Bells Are Ringing for Me and My Gal." James Plath explores this material in his essay The Sun Also Rises as a Greater Gatsby: Isn't It Pretty To Think So?: Although Hemingway's allusion to a lyric is a technique he hadn't used before, it was one which Fitzgerald had recently employed in Gatsby. Hemingway's "coupling" of the Seldes blurb and a wedding-bell song seems indeed a parodic jab at Gatsby and the grand romance contained thereinwhich is made more evident if one tries actually to sing Bill's "lyric" to a melody that simply won't accommodate it rhythmically. Of course Bob Dylan, the guy who accommodated, She says, You cant repeat the past. I say, You cant? What do you mean, you cant? Of course you can. to fit the tune of Big Joe Turners Rebecca, might be up to that task. And Hemingways use of lyrics is also seen in The Snows of Kilimanjaro, where Harry quotes Cole Porters Bad For Me in one of the tiffs over his whiskey-soda. The key point is that not only has Dylan telescoped The Sun Also Rises into one verse of a song, he did it in a way that it ties directly to the following verse, where he presents a thumbnail sketch of The Great Gatsby. In Chronicles: Volume One Dylans concern about the telescoping, via Hemingway, is, if you could get it right. Dylan got it right in Summer Days. I suggest that in the whiskey sauce passage in Chronicles: Volume One Dylan got it right again. Although an underlying meaning in the passage passed by in a puff for Stephen Scobie, the fact that he was so drawn to what Dylan was doing that he felt compelled to write an essay about it speaks to the power of Dylans approach.

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html

12 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html

13 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html

14 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

Posted 21st July by Scott Warmuth

APR

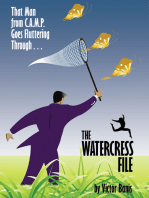

April Fool's Day 2013: Bob Dylan, Revisionist Art and The "Jolene" Smoke Screen

"Lots of places to hide things, you want to hide them bad enough. Ain't like Easter eggs, like Christmas presents. Like life and death." - Larry Brown, Kubuku Rides Again For April Fool's Day 2012 I posted an essay that demonstrates how Bob Dylan incorporated an encounter with an artist who exists only as an April Fool's Day joke into his book Chronicles: Volume One. I also presented how this imaginary artist, Robyn Whitlaw, had in turn been reviewed by the imaginary art critic Flora Gruff. Just barely in time for April Fool's Day 2013 comes the release of Bob Dylan's new book Revisionist Art: Thirty Works . My eyebrows rose when I saw that the book's description includes, "Art critic B. Clavery provides a history of Revisionist Art, from cave drawings, to Gutenberg, to Duchamp, Picasso, and Warhol. The book also features vivid commentaries on the work, (re)acquainting the reader with such colorful historical figures as the Depression-era politician Cameron Chambers, whose mustache became an icon in the gay underworld, and Gemma Burton, a San Francisco trial attorney who used all of her assets in the courtroom. According to these works, history is not quite what we think it is." The "about the author" section adds, "B. Clavery is the editor of Sluggo: A Magazine of the Transformative Arts." A quick check for other work by this B. Clavery turns up nothing beyond the essay for Dylan's book. Sluggo: A Magazine of the Transformative Arts does not appear to exist beyond the reference in the description of the book. It seems that Dylan is using the device of the imaginary art critic. Perhaps he even is the imaginary art critic. The choice of Sluggo as the title of the magazine is an intriguing one. The most obvious Sluggo is the Ernie Bushmiller creation, the pal of Nancy. In his essay "...and Artists and Con Artists..." Kevin McDonough explores Bushmiller's take on fine art: "T o Nancy and Sluggo, artists were always hoaxes, goateed fast-buck hucksters pawning child's play off as 'abstract,' 'modern,' and ultimately incomprehensible art. While gullible adults might fall for these flim-flam men and their wares, Nancy and Sluggo were always ready to laugh at the emperor's new clothes." In 1988 Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik published a groundbreaking essay on Bushmiller titled "How to Read Nancy." In their conclusion they state, "What you may once have considered simple will reveal itself as a complex fabrication of the highest order." I wouldn't presume to write an essay titled "How to Read Bob Dylan," but I can show that one can take that notion from

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 15 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

order." I wouldn't presume to write an essay titled "How to Read Bob Dylan," but I can show that one can take that notion from Newgarden and Karasik and apply it to the work of Bob Dylan. Exploring the devices and techniques used by Dylan reveals that what critics have dismissed as simple and worthless in Dylan's art are actually elaborate constructions. I've established previously that Dylan has read and employed techniques discussed in Robert Greene's The 48 Laws of Power. Law 3 is "Conceal Your Intentions." Greene breaks this law down into two sections. Part one is "Use decoyed objects of desire and red herrings to throw people off the scent" and part two is "Use smoke screens to disguise your actions." Dylan uses material from this section of Greenes book in Chronicles: Volume One. Chronicles: Volume One, p. 212: The song was like looking at words in a mirror and checking out the reverse images. It's like you set up a thick smokescreen and then put the real action ten miles away. The 48 Laws of Power, p. 27: Selassie's way of allaying Balcha's fears letting him bring his bodyguard to the banquet, giving him top billing there, making him feel in control created a thick smoke screen, concealing the real action three miles away. One is able to observe Dylan's effective use of both the red herring and the smoke screen by taking a close look at the song "Jolene" from his 2009 album Together Through Life as well as his most recent interview with Rolling Stone. "Jolene" is a song that Dylan clearly favors, as he has performed it well over one hundred times. It has not fared so well critically. Here's Sean Wilentz on the song in his book Bob Dylan in America: Once more the simplest of the songs can contain layers that approach allusion, but only just. In her 1974 hit Jolene, Dolly Parton pleads with a raving beauty, with flaming locks of auburn hair and eyes of emerald green, begging her not to steal her man. Dylan's Jolene does not even attempt to match Parton's, which is one of the great performances in country-and-western music, but it is an interesting counterpart. In Dylan's version, a toss-off steady rocker with a nice guitar hook, Jolene's eyes are brown and Dylan sings as the king to her queen, while he packs a Saturday night speciala plain enough sex song, but lurking in the lyrics and the music are also hints of Robert Johnson's 32-20 Blues, as well as Victoria Spivey's album recorded in early 1962, Three Kings and the Queen (on which a twenty-year-old Bob Dylan, no king, played harmonica in back of Big Joe Williams). Wilentz, the would-be Dylan detective, is oblivious to the actual hints and illustrates, once again, how he fills the role of the tired beat cop who tells onlookers, "Nothing to see here folks, move along." Clinton Heylin expresses a particularly dismissive view of "Jolene" in his book Still On The Road: The Songs of Bob Dylan: Vol. 2: 1974-2008: For a ditty that could as easily have been called Baby I Am The King to invite comparison with Dolly Parton's consummate song of the same name suggests a certain chutzpah on the singer's part. In the past, one would have expected such bravado to generally have been warranted. But this is truly desperate stuff. Line after line of missing links, it is tuneless, hopeless, almost worthless too. What is hopeless and almost worthless is his assessment. The red herring has taken him far down the wrong path as well. The red herring is Dolly Parton's song of the same name. It is so powerful that Wilentz and Heylin are not able to see past it. Bill Flanagan asked Dylan about Parton's song, resulting in this exchange: Flanagan: Any chance your Jolene is the same woman who got Dolly Parton so worked up? Dylan: You mean that woman with the flaming locks of auburn hair? Flanagan: Yeah! Who's smile is like a breath of Spring. Dylan: Oh yeah, I remember her. Flanagan: Is it the same one? Dylan: It's a different lady. In this case Dylan is telling the truth - it is a different lady. The lady that he had in mind has a similar name, and she was the subject of a song that was a bigger pop hit than Parton's "Jolene." The song is "Rolene," a T op 40 hit in 1979 for composer Moon Martin. In this case the cover version by Willy DeVille's band Mink DeVille is the one to consider. A close look at the lyrics to Dylans "Jolene" reveals that it is comprised almost entirely of lines from songs found on the Mink DeVille albums Cabretta and Return To Magenta. I first wrote about connections between Willy DeVille and Together Through Life back in 2009, before the album was released. At the time I pointed out that the song "This Dream of You" begins with, How long can I stay in this nowhere caf? and how this echoes the Doc Pomus/Willy DeVille composition "Just T o Walk That Little Girl Home" and its opening line "It's closing time in this nowhere caf." Dylan had mentioned Doc Pomus in that Flanagan interview, so it was natural to look at the Doc Pomus catalog. Besides the song "Rolene" there are eight other Mink DeVille songs to consider. Dylan used a similar method of construction in the song "Tweeter and the Monkey Man," which is a pastiche of Bruce Springsteen song titles and themes. That one is obvious to even the most casual listener. In "Jolene" Dylan tweaks the formula by making the homage distinctly more difficult to recognize. First verse of "Jolene": Well you're comin' down High Street, walkin' in the sun You make the dead man rise, and holler she's the one Jolene, Jolene Baby, I am the king and you're the queen The connection in that first line is to the David Forman (aka Little Isidore) composition "'A' Train Lady ." High Street is mentioned

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 16 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013

five time in the fade out of the Mink DeVille version: "Following you all the way to High Street/Yes, I followed you to High Street/And I wished you were my baby/All the way, all the way/All the way to High Street/All the way, all the way/All the way to High Street/All the way, all the way/All the way to High Street." The second line in "Jolene" is the first of a pair of lines that originate in the song "Cadillac Walk." That song includes, "dead men raise and sigh." "Cadillac Walk" is another song that was written by Moon Martin. In "Tweeter and the Monkey Man" Dylan namechecks "Jersey Girl" - a song written by T om Waits, but familiar through the version by Springsteen. By having two of his songs referenced one could consider Moon Martin to be the Tom Waits of "Jolene." Not only is the repeated "Jolene, Jolene" an echo of "Rolene, Rolene" from the song "Rolene," but there is a distinctive guitar hook in the chorus of the Mink DeVille version that was likely the starting point for the guitar line that is played in the refrain of the Dylan song. Second verse of "Jolene": Well it's a long old highway, don't ever end I've got a Saturday night special, I'm back again I'll sleep by your door, lay my life on the line You probably don't know, but I'm gonna make you mine The Mink DeVille song "Steady Drivin' Man" includes both "You know that long old highway" and "She's got a Saturday night special." The third line is built out of bits from the song "Just Your Friends": "You know that all of the time I've laid my heart on the line" and "I don't know why I want more but I will sleep by your door for the truth." The second part of the couplet is taken from the Mink DeVille recording of "Little Girl" (a cover of the Phil Spector/Ellie Greenwich/Jeff Barry composition "Little Boy," a hit for the Crystals). DeVille starts his version off with, Little girl, you probably don't know it." Third verse of "Jolene": I keep my hands in my pocket, I'm movin' along People think they know, but they're all wrong You're something nice, I'm gonna grab my dice I can't say I haven't paid the price The first line of the third verse is right out of the song "Desperate Days": "Put your hands in your pockets, you keep moving around." With the third line Dylan is back to "Cadillac Walk," reworking the line, "Ain't she something nice/Bones rattle my dice." Dylan rhymes the "dice" line with "I can't say I haven't paid the price," which is from the Mink DeVille song "Soul Twist": "No, I can't say that you haven't paid the price." Final verse of "Jolene": Well I found out the hard way, I've had my fill You can't fight somebody with his back to a hill Those big brown eyes, they set off a spark When you hold me in your arms things don't look so dark Dylan begins the final verse with more from the song "Soul Twist ," the first line: "I found out the hard way." In Moon Martin's original recording of "Rolene" he sings about her thighs. Willy DeVille took some liberties and changed that line to be about Rolene's "big brown eyes." Dylan finishes the final verse with, "When you hold me in your arms things don't look so dark" and that is straight out of the song "Guardian Angel": "When you hold me in your arms, things don't look so dark no more." One of the few lines in "Jolene" that doesn't appear to come from a Mink DeVille recording is, "People think they know, but they're all wrong." One can apply that to Sean Wilentz's notion that "Jolene" is a plain and simple toss-off with "layers that approach allusion, but only just." He couldn't be more wrong, as the song is a complicated construction that is almost entirely allusion. Just because he fails to recognize the allusions he seems to think that they don't exist. What Clinton Heylin sees as, "Line after line of missing links" is anything but. The links to the first seven songs from Mink Deville's Return to Magenta, as well as two of the songs from Cabretta, are right there - if one can dismiss the red herring and get past the smoke screen. When considering if there was evidence of Dylan showing any interest in the music of Willy DeVille during the time when the songs on Together Through Life would likely have been written I came across a telling anecdote in a 2011 interview with musician Paul James conducted by Lisa McDonald that ran in smalltowntoronto.com. Beyond his own career Paul James played with Bo Diddley regionally for decades and has shared the stage with Dylan (and Dylan with him) many times, going back to 1986. Paul James did a stretch as the touring guitarist for Mink Deville and is featured prominently on the DVD Mink DeVille: Live at Montreux 1982, which was released in April of 2008. James also wrote and recorded a song about his tenure with Mink DeVille, a reggae tune about what you end up doing when your band leader is "kicking the gong around" called "Waiting For Willy." In the interview Paul James talks about an encounter he had with Dylan in August of 2008: "I parked my van right in front of Dylans bus at Copps Coliseum, like I was told. And then these guys came and took me to my seat. I was then told, 'Right after the encore, well come back and bring you to Bob. He wants to talk to you.' When I was taken to see Bob, the first thing he says to me is, 'Hey, I saw that video where you played with Mink DeVille. Willy is something else.' (Willy was still alive at this point). We talked about Mink DeVille and then Dylan said, 'You think you could play guitar for me?' I said, 'Yea!'" On Mink DeVille: Live at Montreux 1982 Willy straps on an acoustic guitar and a harmonica rack for the song "Just Your Friends"

http://swarmuth.blogspot.fr/#!/2013/03/april-fools-day-2013-bob-dylan.html 17 / 46

Goon Talk

14/11/2013