Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Federal Reserve

Uploaded by

shamyshabeerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Federal Reserve

Uploaded by

shamyshabeerCopyright:

Available Formats

FEDERAL RESERVE

BY R E N E E H A LT O M

Reaching for Yield

Are the Feds low interest rate policies pushing investors toward risk?

This time, some Fed policymakers have also voiced concerns about reaching for yield. Fed Governor Jeremy Stein has been the most vocal, detailing what he views as causes of excessive risk in a February speech, and Bernanke and Vice Chair Janet Yellen have said that the Fed is watching the issue. They all agree on one thing: Greater risk-taking and the failure of any one firm if those bets go bust is not necessarily a concern for policymakers. The problem could be if many investors suffer losses on these risks at the same time, or if they enter into them in ways that could bring other institutions down. With the financial crisis fresh in regulators memories, should the Fed be concerned that its low rates are planting the seeds for the next crisis?

t may surprise some people to learn that the Federal Reserve, despite being one of the nations most important financial regulators, sometimes intentionally encourages investors to take on risk. Thats a key function of monetary policy after a recession. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke has called it a return to productive risk-taking. When the Fed lowers the federal funds interest rate, its main policy instrument, other market rates tend to fall, making it more attractive for entrepreneurs to raise money for startups and for existing businesses to expand capacity. Thats one way low interest rates help to spur economic recoveries. But what about people who earn a living by lending money? The worlds largest investors are insurance companies, pension funds, and mutual funds, which collectively hold $24 trillion in assets. They invest heavily in bonds, together holding $4.7 trillion in corporate and foreign bonds, among other types, so their returns are very sensitive to interest rates. These investors often owe their clients guaranteed payouts through insurance policies, annuities, and pensions. In those cases, a low interest rate environment doesnt just squeeze profits, it could risk insolvency. When interest rates fall, they may have no alternative but to seek out riskier investments, wrote economist Raghuram Rajan, then the chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, back in 2005. He was one of the first to raise concerns that investors are forced to reach for yield when interest rates are low. If they stay with low return but safe investments, they are likely to default for sure on their commitments, while if they take riskier but higher return investments, they have some chance of survival. (Rajan recently left the University of Chicago to head the central bank of India.) His words were written in what was then a period of remarkably low interest rates. Theyre even lower today. The Feds policy rates have been effectively at zero since December 2008, and the Fed has said theyll stay there until unemployment comes down significantly. Not only have short-term rates been lower and for a longer period than in any episode since the Great Depression, but long-term rates are remarkably low as well, thanks to the Feds unconventional monetary policies like quantitative easing and Operation Twist. For the worlds biggest bond investors, returns have been squeezed at all parts of the yield curve.

Rationalizing a Reach

Why would rational, self-interested investors willingly take on too much risk? To be clear, reaching for yield is not about investors making mistakes. Nor is it about the normal competitive forces that make firms anxious to outperform one another. These forces are always present, and theres no reason to believe they change much over time. There are several reasons investors might suddenly take on more risk than usual. Banks whose capital has been depleted following a financial crisis, leaving them vulnerable in the event of any new losses, might make Hail Mary investments to try to restore their financial positions, especially if they think a government safety net is waiting. Financial innovation might create new opportunities to take advantage of gaps in regulation. In fact, Stein said in February, any time the rules of the game change new regulations, accounting standards, or performance-measurement, governance, and compensation structures an unintended consequence can be new incentives for risk. But the kind of reaching for yield that Stein, Yellen, Bernanke, and Rajan have discussed recently stems from low interest rates. When nominal market interest rates are generally high, investment managers have no problem earning enough to cover their liabilities or reach their investment goals. But after a recession, the central bank may cut interest rates to boost the economy. For a while, risk premia remain elevated, pushing overall market interest rates higher, so investors have little need to search for yield. As risk premia recede, however, investors may become desperate for higher returns and shift toward riskier investments. Life insurers, for example, are a significant chunk of the financial sector. They hold $5.7 trillion in assets, more than a third the size of the entire traditional banking sector, and hold 17 percent of all corporate and foreign bonds outstanding in the United States. Life insurance companies

ECON FOCUS | THIRD QUARTER | 2013

Interest Rates Are Rarely as Low as They Have Been Recently

20 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0

Baa Corporate Bonds Aaa Corporate Bonds 10-Year Treasury Federal Funds Rate

1980 1990 2000 1970 2010 SOURCE: Moodys and Haver Analytics. Data through November 2013.

collect payments from their clients that they invest in order to repay under prescribed conditions. When interest rates fall, the insurer falls further from the return that ensures its ability to make those payouts. Moreover, some life insurance products come with riders that guarantee minimum returns regardless of what the insurer can actually earn on its investments. In 2010, nearly 95 percent of all life insurance policies contained a minimum interest rate guarantee of at least 3 percent, and 70 percent of life insurer annuities with such guarantees had a minimum of at least 3 percent in a period in which long-term Treasuries, a good indicator of insurers returns, traded close to or below 3 percent, according to a recent Chicago Fed study. That study found that the low interest environment has been hard on life insurers. The returns of large insurers become more sensitive to interest rates in low-rate environments, they found. The stock prices of insurance companies fell in recent years while the rest of the market rose, and 45 percent of life insurance company CFOs said in a 2012 survey that prolonged low interest rates are the single greatest threat to their business model. Hedge funds may also have incentive to reach for yield, Rajan argued in 2005. Hedge fund managers are compensated based on the amount by which their nominal returns exceed some minimum threshold. When market interest rates are high, compensation is high without the hedge fund having to gamble excessively for it. If rates are low, the fund may risk missing the threshold entirely. The only way to generate high returns may be to add risk. But arent investment managers required by regulations or the preferences of their clients to stay within certain risk buckets? They are. But risk measures, such as credit ratings, are necessarily broad; investments have finer degrees of risk not captured by broad measures. Its not hard for investment managers to take on more risk through investments that are longer-term, more complex, less liquid, or more leveraged while staying within requirements. Risk measurements are like weight classes for boxers, says Bo Becker, professor of finance at the Stockholm School of Economics. Weight is really important to how powerful you are as a boxer, Becker notes. Theres a lot of gaming around weight classes its really ideal to be at the top of the class. You see the same thing with a professional

6

ECON FOCUS | THIRD QUARTER | 2013

investment manager who is given a risk bucket. They still have scope to take on a lot of risk or a little risk. Regulators can use judgment to probe beneath objective measures of risk; in fact, the 2010 Dodd-Frank regulatory reform act requires them to do just that, moving away from credit ratings. But thats harder to do in the case of complex securities, such as certain structured bonds that are built on other assets rather than being a claim to something real, like a commodity or a stake in a company. The more illiquid or complex the investment, the harder it is to assess risk, which is why reaching for yield may be more likely to occur in opaque areas of financial markets. Ultimately, the DoddFrank Acts move to abandon ratings doesnt solve the problem, Becker says, because for any functional definition of risk, there will always be gradation that is hard for regulators to see. Delegated investment management when investors manage funds owned by somebody else has grown considerably over the last 50 years, starting with the rise of insurance companies and pensions. The scope for reaching for yield is bigger than ever, Becker says. But that doesnt mean reaching for yield is always happening. Thats where long periods of low interest rates come in. Market interest rates are rarely as low as they have been recently (see chart). From the 1970s until the early 2000s, bond yields were relatively high. After the tech bust in the early 2000s, the Feds policy rate hit 1 percent in June 2003, near a record low. It stayed there for a year, spurring concerns such as those raised by Rajan. Thus, the Fed has not had to confront the possibility of reaching for yield until the past decade.

PERCENT

Reaching for Evidence

The evidence of reaching for yield is hard to come by, which is one of the challenges for regulators. Its hard to see in price data because you dont have any reference on whats a fair price, says Viral Acharya, professor of economics and finance at the New York University Stern School of Business. Observers have been pointing to some market-based signs of excessive risk, but with little certainty about what they mean. A particular concern recently and a major theme of this years annual August gathering of prominent economists in Jackson Hole, Wyo. is that very low interest rates could be fueling speculative asset bubbles around the globe. For example, Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, noted that cumulative net flows to emerging markets have risen by more than $1 trillion since 2008, an estimated $470 billion above trend. A recent study from the New York Fed found that low Treasury yields have been the main factor driving excess returns in the U.S. stock market to a historic high. Sometimes the evidence is not in prices, but in asset managers suddenly doing something new. Youll see certain kinds of asset managers engage in a lot more of a particular activity than others, Acharya says.

In a study from earlier this year, Becker and Victoria Ivashina at Harvard Business School published some of the limited hard evidence that exists of those activities. Insurance companies are required by regulation to hold a certain amount of capital based on the risk level of their portfolios, to increase the chances that they can meet their liabilities even in bad times. But they systematically buy the riskiest bonds available within the safe asset categories that equate to low capital requirements, Becker and Ivashina found. Leading up to the financial crisis, insurance companies held 72 percent of all the issuances of the safest quartile of investment-grade bonds, but 88 percent of the riskiest quartile of those bonds. By comparison, pension and mutual funds, which arent constrained by capital requirements, did not engage in this behavior. (That doesnt mean pension and mutual funds dont reach for yield; it would just manifest itself differently, Becker and Ivashina argued.) Both interest rates and risk premia were particularly low by historical standards during this period. Reaching-foryield behavior disappeared during the crisis, when investors were likely to be more cautious. But as soon as the crisis receded, reaching for yield ramped up again. They also found that reaching for yield is correlated with higher bond issuance by riskier firms, which obtain funding more cheaply than they would under normal conditions. Another reason reaching for yield is challenging to identify is that it wont necessarily show up in price data at all for example, yields on junk bonds converging toward riskfree rates. Risk doesnt necessarily appear in rates because it can also be manifested in subtler, nonprice ways, Stein said in his February speech. For example, investors can make loans with fewer covenants, which are safety thresholds that can protect the bond holder. Or they can agree to low levels of subordination, which means they are among the last of all investors to be paid out, and thus the first to bear losses. There is some evidence that reaching for yield may be taking these forms, Stein said. Research by Robin Greenwood and Samuel Hanson at Harvard Business School found these nonprice risks tend to be correlated with the amount of bonds being issued by risky borrowers. The highyield share of issuances, in turn, has recently been above its historical average, Stein said. Additionally, issuance of covenant-lite loans and other nonprice risk characteristics in 2012 were comparable to just before the financial crisis. For policymakers, the concern is whether the risks have systemic implications. Even if riskier bets turn out badly for a few or even many firms, that doesnt mean well experience another financial crisis. For the risks to have systemic implications, they may have to be combined with other risky behaviors. One is leverage funding risky activities by borrowing. A firm is on the hook for paying those debts back even if its investments go bad, leaving it at risk for insolvency. Low interest rates, of course, make borrowing and therefore leverage more attractive. Another risky behavior could be maturity transformation, or funding long-

term investments with short-term instruments, such as repurchase agreements, that are subject to runs as investors quickly pull back at the first sign of trouble. Both behaviors could leave investors especially vulnerable to market reversals, and some economists have argued that they were key sources of systemic risk prior to the recent financial crisis. Normally, markets should be expected to place limits on risk-taking; investors have an incentive to withdraw funding when things get out of hand when single firms take excessive risks or when entire asset classes start to look overvalued. Economists have long debated why investors might sometimes think they will be shielded from bad outcomes. Some favor behavioral explanations, such as investors herding into similar risks because they know a bad outcome wont make them look worse relative to competitors who took the same risks. Another possibility is that the markets ability to limit risk-taking is reduced when investors expect the government to step in and prevent losses, as it did during the financial crisis.

What Policy Could Do

Fed policymakers have said the evidence of reaching for yield, especially with the potential for serious systemic effects, is still limited. But since the financial crisis, regulators have become more eager to explore hypotheticals. That discussion has focused on which of the Feds tools is most appropriate to fight reaching-for-yield behavior should it escalate. There are two choices: monetary policy or regulation. Before the crisis, central bankers argued that monetary policy should not be used to pop asset bubbles preventatively, a view so widely held that it was dubbed the Jackson Hole consensus. Bernanke and Mark Gertler at New York University encapsulated that consensus in a 1999 paper: policy should not respond to changes in asset prices, except insofar as they signal changes in expected inflation. Central banks cannot identify asset bubbles in advance, they argued, and even if they could, monetary policy is too blunt a tool; it could only deflate an asset bubble by taking down the rest of the economy with it. Historically, central banks have tended to use monetary policy only to clean up the residue from bubbles after they burst. Regulation, instead, has been the preferred tool for managing risk. It is certainly a more precise tool. The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act instructed the Fed and other regulators to take a macroprudential approach to financial regulation that is, to ramp up their surveillance of risks that spread from one institution to the next, such as those that might result from excessive leverage or maturity transformation. The downside of regulation has always been that examiners will never be able to see every place that risk lies. Stein argued that seemingly innocuous cases of reaching for yield can imply that more of it is happening where we cant see it. So we should be humble about our ability to see the whole picture, he said. For that reason, Stein said, regulators might not want to

ECON FOCUS | THIRD QUARTER | 2013

rule out tighter monetary policy as a tool for limiting risky behavior. [W]hile monetary policy may not be quite the right tool for the job, it has one important advantage relative to supervision and regulation namely that it gets in all the cracks. Would using monetary policy in this way be trying to exert too much influence over investor behavior, causing market distortions? Some policymakers, including Richmond Fed President Jeffrey Lacker, have argued though not in the context of reaching for yield that trying to affect markets through monetary policy in anything other than a broad-based way is not an appropriate role for the Fed. In several 2013 appearances, Bernanke said that while reaching for yield was a risk, it didnt appear to be prevalent enough to outweigh the benefits of easier monetary policy to support the economic recovery which itself can aid financial stability.

A Moot Point For Now?

Longer-term market rates have risen recently following discussion from Bernanke about the Feds potential exit READINGS

Becker, Bo, and Victoria Ivashina. Reaching for Yield in the Bond Market. Forthcoming in the Journal of Finance. Berends, Kyal, Robert McMenamin, Thanases Plestis, and Richard J. Rosen. The Sensitivity of Life Insurance Firms to Interest Rate Changes. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Economic Perspectives, Second Quarter 2013. Rajan, Raghuram G. Has Financial Development Made the World Riskier? Paper presented at The Greenspan Era: Lessons for the Future, a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City in Jackson Hole, Wyo., Aug. 25-27, 2005.

from the stimulative policies it employed during the recession that have kept interest rates low. On May 22, Bernanke said the Fed could slow, or taper, its monthly $85 billion purchases of new assets by the end of the year if the economic recovery remained on track. Long-term Treasury yields immediately jumped in response, reaching as high as they had been in more than two years. Investors quickly fled from emerging market equities, and their currencies fell. The market volatility in response to the tapering discussion is a sign of reaching-for-yield behavior being unwound, Acharya says. Its clear that there will be dislocations if they are unwinding with even the hint of a taper, he says. Slowing down new asset purchases is a less strong step than selling the stock of assets the Fed already holds, which is itself a far cry from actually raising the federal funds rate. But even if interest rates dont return to their record lows for a while, regulators may continue to view reaching for yield as a concern as monetary policy moves into a less aggressive phrase and as bond investors continue to struggle with low returns. EF

Stein, Jeremy. Overheating in Credit Markets: Origins, Measurement, and Policy Responses. Speech at the Restoring Household Financial Stability After the Great Recession: Why Household Balance Sheets Matter research symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, St. Louis, Mo., Feb. 7, 2013. Y ellen, Janet. Assessing Potential Financial Imbalances in an Era of Accommodative Monetary Policy. Speech at the 2011 International Conference at the Bank of Japan, Tokyo, Japan, June 1, 2011.

about a current economic issue or trend. The essays are based on research by economists at the Richmond Fed. December 2013

How Risky Are Young Borrowers?

Look for our next Economic Brief

The Effects of Fiscal Policy Uncertainty

To access the Economic Brief and other research publications, visit www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/

ECON FOCUS | THIRD QUARTER | 2013

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Digital Image Processing Question Answer BankDocument69 pagesDigital Image Processing Question Answer Bankkarpagamkj759590% (72)

- Global Economic Growth FaltersDocument4 pagesGlobal Economic Growth FaltersshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- The Demographic Shift From Single-Family To Multifamily HousingDocument30 pagesThe Demographic Shift From Single-Family To Multifamily HousingshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- The Productivity ParadoxDocument6 pagesThe Productivity ParadoxshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Are Recent College Graduates Finding Good JobsDocument8 pagesAre Recent College Graduates Finding Good JobsshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Linear ModelsDocument30 pagesLinear ModelsshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Chicago Fed LetterDocument4 pagesChicago Fed LettershamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Working Paper No.14-3Document56 pagesWorking Paper No.14-3shamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Cover StoryDocument4 pagesCover StoryshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Economic LetterDocument4 pagesEconomic LettershamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- InterviewDocument5 pagesInterviewshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Employment ProjectionsDocument13 pagesEmployment ProjectionsshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Feature 2Document3 pagesFeature 2shamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Economics Small Open EconomiesDocument10 pagesEconomics Small Open EconomiesshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Rushing Into American DreamDocument51 pagesRushing Into American DreamshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Breaking Ice Govt Interventions Frozen MarketsDocument7 pagesBreaking Ice Govt Interventions Frozen MarketsshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Relationship Between Life Insurers and The Federal Home Loan BanksDocument3 pagesUnderstanding The Relationship Between Life Insurers and The Federal Home Loan BanksshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- SuThe Impact of Debit Card Regulation On Checking Account FeesllivanDocument36 pagesSuThe Impact of Debit Card Regulation On Checking Account FeesllivanshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Has Durable Goods Spending Become Less Sensitive To Interest Rates?Document23 pagesHas Durable Goods Spending Become Less Sensitive To Interest Rates?shamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Debt DilutionDocument8 pagesDebt DilutionshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Agglomeration in The European Automobile Supplier IndustryDocument28 pagesAgglomeration in The European Automobile Supplier IndustryshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- The Rising Gap Between Primary and Secondary Mortgage RatesDocument23 pagesThe Rising Gap Between Primary and Secondary Mortgage RatesshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Human Capital and Long - Run Labor Income RiskDocument30 pagesHuman Capital and Long - Run Labor Income RiskshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Residential Migration, Entry, and Exit As Seen Through The Lens of Credit Bureau DataDocument36 pagesResidential Migration, Entry, and Exit As Seen Through The Lens of Credit Bureau DatashamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Swe1304cyou Can Go Home Again: Mexican Migrants Return in Record NumbersDocument2 pagesSwe1304cyou Can Go Home Again: Mexican Migrants Return in Record NumbersshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Shadow BankingDocument16 pagesShadow BankingsotozenNo ratings yet

- The Impact of An Aging U.S. Population On State Tax RevenuesDocument34 pagesThe Impact of An Aging U.S. Population On State Tax RevenuesshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- Swshale Revolution Feeds Petrochemical Profits As Production Adaptse1304gDocument4 pagesSwshale Revolution Feeds Petrochemical Profits As Production Adaptse1304gshamyshabeerNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HDFC CMS Ops SUMMER INTERNSHIP REPORTDocument45 pagesHDFC CMS Ops SUMMER INTERNSHIP REPORTpremNo ratings yet

- Radiowealth Finance Company vs. Del Rosario, 335 SCRA 288, July 06, 2000Document13 pagesRadiowealth Finance Company vs. Del Rosario, 335 SCRA 288, July 06, 2000TNVTRLNo ratings yet

- Front Office AccountingDocument9 pagesFront Office AccountingIga Asti AstriaNo ratings yet

- Solutions Manual Chapter Twenty-Three: Answers To Chapter 23 QuestionsDocument12 pagesSolutions Manual Chapter Twenty-Three: Answers To Chapter 23 QuestionsBiloni KadakiaNo ratings yet

- PWC Colonial Liability Order 122817Document92 pagesPWC Colonial Liability Order 122817Daniel Fisher100% (1)

- Hallmark ImportantDocument3 pagesHallmark ImportantSourav GhoshNo ratings yet

- Performance Evaluation of Selected Ceramic Companies of BangladeshDocument14 pagesPerformance Evaluation of Selected Ceramic Companies of BangladeshmotaazizNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: Business Plan PreparationDocument26 pagesChapter Three: Business Plan PreparationwaqoleNo ratings yet

- ADVACCDocument3 pagesADVACCCianne AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Housing Loan Taken From Vysha Co Operative Bank (Autosaved) (Repaired)Document97 pagesHousing Loan Taken From Vysha Co Operative Bank (Autosaved) (Repaired)roja donthiNo ratings yet

- Bank Notes SecretsDocument99 pagesBank Notes Secretssavedsoul2266448100% (12)

- Negotiable InstrumentsDocument22 pagesNegotiable InstrumentsPrince Mittal100% (1)

- Global Optical CaseletDocument1 pageGlobal Optical Caseletchandan tiwariNo ratings yet

- RBI Circular On Export Finance - 1Document21 pagesRBI Circular On Export Finance - 1Anonymous l0MTRDGu3MNo ratings yet

- Forms MasterFormIndexDocument39 pagesForms MasterFormIndexYeshua Sent MessengerNo ratings yet

- RTP - I Group PDFDocument177 pagesRTP - I Group PDFMadan SharmaNo ratings yet

- PNB V BacaniDocument20 pagesPNB V BacaniyousirneighmNo ratings yet

- Basic Documents and Transactions Related To BankDocument31 pagesBasic Documents and Transactions Related To BankJerima PilleNo ratings yet

- TR 256 - Top Income Shares in GreeceDocument28 pagesTR 256 - Top Income Shares in GreeceKOSTAS CHRISSISNo ratings yet

- RockRiverTimes 03282018 CLASSDocument2 pagesRockRiverTimes 03282018 CLASSShane NicholsonNo ratings yet

- Montgomery V Etreppid # 1086 - Montgomery DeclarationDocument6 pagesMontgomery V Etreppid # 1086 - Montgomery DeclarationJack RyanNo ratings yet

- Audit of The Financing and Investing Cycle ReportDocument20 pagesAudit of The Financing and Investing Cycle ReportCyrell S. SaligNo ratings yet

- L3 Passport To Success - Solutions BookletDocument52 pagesL3 Passport To Success - Solutions BookletCharles MK ChanNo ratings yet

- Keown Tif 20 FINALDocument31 pagesKeown Tif 20 FINALhind alteneiji100% (1)

- Aegon 12 FullDocument4 pagesAegon 12 Fullapi-3705095No ratings yet

- Loan Account Statement Details: Generated byDocument7 pagesLoan Account Statement Details: Generated byMd. Shahidul Islam PkNo ratings yet

- Web of Debt - Thinking Outside The Box: How A Bankrupt Germany Solved Its Infrastructure ProblemsDocument4 pagesWeb of Debt - Thinking Outside The Box: How A Bankrupt Germany Solved Its Infrastructure Problemssuperdude663No ratings yet

- Train Law Excise Tax 1Document29 pagesTrain Law Excise Tax 1Assuy AsufraNo ratings yet

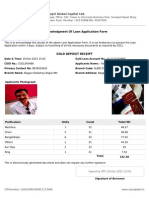

- Acknowledgment of Loan Application Form: Capri Global Capital LTDDocument9 pagesAcknowledgment of Loan Application Form: Capri Global Capital LTDRahul MahankalNo ratings yet

- Sample Family Agreement1 PDFDocument9 pagesSample Family Agreement1 PDFShelleyMaeSilaganMartosNo ratings yet