Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adaptation of Shiva Practice in Tantric Buddhism

Uploaded by

pranajiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adaptation of Shiva Practice in Tantric Buddhism

Uploaded by

pranajiCopyright:

Available Formats

Ixiriarixc rui Moxaicu:

rui aoairariox oi a

Saiva iiacrici ioi rui

iioiacariox oi Esoriiic Buoouisx ix Ixoia,

Ixxii Asia axo rui Fai Easr

Alexis Sanderson

December :o, :cc

OPEN LECTURE, UNIVERSITY OF TOKYO

ABSTRACT

:

Our evidence for the history of the religions of India in premodern times

is overwhelmingly in the form of texts that tell their audiences what they

should do and think but reveal little of what was actually done and thought.

They convey even less that would enable us to understand the demography

of these religions and the social, political, and economic history of their

institutions. Where historians of other literate civilizations can draw on

archives, ocial and private histories, diaries, biographies and the like we

are limited almost entirely beyond our prescriptive texts to the evidence

provided by the epigraphical and archaeological record; and that is both

lacunose and parsimonious.

The textual scholar may feel that this poverty of non-prescriptive data

does not seriously distort the understanding that he can form from the rich

body of texts at his disposal. Indeed he may even feel justied in remaining

in ignorance of this evidence, believing that he is true to the spirit of the

texts themselves in considering that what he lacks or overlooks are mundane,

ephemeral, and peripheral details that were of no importance to his authors.

However, if his task is to understand their intentions, he should accept

that this resides not merely in what they state but also in relations between

:

This lecture and its abstract are based on Alexis Saxoiisox, Religion and the State: Initiating the Monarch in

Saivism and the Buddhist Way of Mantras. Part : of Rituals in South Asia: Text and Context edited by J. Gengnagel,

U. H usken, and S. Raman, Heidelberg Ethno-Indological Series I-II. Harrassowitz (forthcoming).

:

what they state and what they know their audience knows about itself and

its context in the wider world. Now this unstated information may be

doctrinally neutral and it may be lacking simply because there was no need to

state what was obvious to those to whom the text was addressed. But there is

important information of another kind, information known to the audience

that authors keep unstated or understated or avoid thinking through because

it does not t comfortably into the picture of the religion that they wish

to present. Such tensions are only to be expected. Religions, if they are

successful in the world, can nd that they have accepted compromises that

their theologians may be unable or disinclined to understand and justify.

This was certainly so among the

Saivas.

I have discussed elsewhere the case of the

Sr addha rituals that the

Saivas

came to perform for their deceased initiates in conformity with brahmanical

norms, even though the central promise of their religion was that the

ceremony of initiation destroyed the bonds of the soul so that the initiate

would attain liberation at death, and therefore be in no need of such

oerings.

:

Here I shall present evidence of another important respect in

which they were prepared to consolidate their position in the world at the

expense of doctrinal consistency, namely by tying themselves to the monarch

and the monarch to them.

I nd four major aspects of the interaction of

Saiva Gurus with royalty

evidenced in inscriptions and/or reected in the

Saiva literature. These are:

:. the creation, empowerment and supervision of royal temples;

:. the performance of re rites (agnik aryam, homah

.

) for Siddhis, the

accomplishment of supernatural results of protection, attraction, ex-

pulsion, weather control, destruction and the like for the benet of

royal patrons wishing to secure the prosperity of their realm and the

confounding of their enemies;

,. the development of an apparatus of rituals enabling

Saiva Gurus to

take over the traditional role of the brahmanical royal chaplain (r aja-

purohitah

.

);

,

and

. the practice of giving

Saiva Man

.

d

.

ala initiation (dks

.

a, sivadks

.

a, sivama-

n

.

d

.

aladks

.

a) to the king as a key element in the ceremonies that legiti-

:

Alexis Saxoiisox, Meaning in Tantric Ritual, in A.-M. Blondeau and K.Schipper (eds), Essais sur le Rituel

III: Colloque du Centenaire de la Section des Sciences religieuses de l

Ecole Pratique des Hautes

Etudes, Biblioth` eque

de l

Ecole des Hautes

Etudes, Sciences Religieuses, Louvain-Paris: Peeters, :,,,, pp. ,,o.

,

The third of these aspects of interaction is the subject of Alexis Saxoiisox, Religion and the State:

Saiva

Ociants in the Territory of the Brahmanical Royal Chaplain with an Appendix on the Provenance and Date of

the Netratantra, Indo-Iranian Journal, :cc iii (forthcoming).

:

mated his oce and added to his regal lustre.

This last practice was crucial to the fortunes of the religion, but it was

one that received so little attention in the prescriptive and commentatorial

literature, compromising as it did the purely spiritual purpose of initiation,

that it has been overlooked in the study of that literature. Here the evidence

of inscriptions and other historical records proves indispensable to the

development of a more rounded picture of the religion and prompts us,

moreover, to return to the

Saiva literature to discover that there are after

all clear traces of the practice within it, albeit mostly in works that as yet

are available only in their primary evidence, that of surviving manuscripts.

Notable among these unpublished sources are (:) the Kal adks

.

apaddhati

of the Kashmirian

Saiva Gurus, composed by Manodaguru in a.o. :,,,/o

but variously expanded during subsequent centuries to produce distinct

versions, and (:) the Naimittikakarm anusandh ana of Brahmasambhu of

M alava, composed in a.o. ,,, the oldest of the surviving Paddhatis, that is

to say, of the post-scriptural guides for ociants that set out the procedures

and Mantras for the performance of the

Saiva cermonies. The second

of these works is particularly revealing, since it treats the initiation and

consecration of the monarch, the chief queen (agramahis

.

) and the crown

prince (yuvar ajah

.

) at length, devoting a separate section to the topic, unlike

the later Paddhatis of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, beginning with

the unpublished Siddh antas arapaddhati of Mah ar aj adhir aja Bhojadeva of

Dh ar a (r. a.o. :c: to :coc) and the published Kriy ak an

.

dakram aval of

Somasambhu (the Somasambhupaddhati), composed in a.o. :c,,/o. For

those works and their successors make no direct reference to the practice.

We will see from this collation of epigraphical and prescriptive textual

evidence

:. that fromthe early seventhcentury onwards inIndia andfromthe tenth

century onwards among the Khmers of mainland Southeast Asia royal

Saiva initiation was a well-established convention in those kingdoms,

the majority, in which

Saivism was the principal recipient of royal

patronage,

:. that royal initiation was conated by the

Saiva ociants with the

brahmanical royal consecration ceremony (r ajy abhis

.

ekah

.

), so moving

from the private into the civic domain; and

,. that in references to it outside the technical literature it was cut adrift

from its theologically dened function to be openly promoted as a

means of sanctifying royal authority and enhancing royal power.

,

In this form it was indeed a powerful means of propagating the religion.

It was rewarded through the daks

.

in

.

a paid to the ociant who performed

the ceremony with a lavishness that enabled the

Saiva monastic network to

spread out into new regions and raised the leading pontis to an authority

that reached far beyond the connes a single kingdom.

The

Saiva practice of royal Man

.

d

.

ala initiation (sivaman

.

d

.

aladks

.

a) was

among the elements of

Saivism that Indian Mah ay ana Buddhists chose to

adopt when they adapted

Saiva ritual models to their own Buddhist purposes

inconstructing their Way of Mantras (Mantranaya, Mantray ana, Vajray ana).

Evidence of Buddhist royal initiation following the Mantranaya is present

for India, though it is slight. But we have abundant evidence of its practice as

a means of propagating the Buddhist faith in Tang China and, following that

example, in Japan from the ninth century onwards. It is also a conspicuous

element in the history of the propagation of Tibetan Buddhism in Inner

Asia among the Mongols, and in China during the Yuan, Ming and Qing

dynasties.

Now this evidence of Buddhist royal Man

.

d

.

ala initiation belongs to two

separate transmissions out of India. The rst occurred in the eighth century,

exporting the formof the Mantranaya that survives to this day inthe Japanese

Shingon-shu and the taimitsu of the Tendai-shu. The second, that began in

the tenth century, brought to Tibet and thence to Inner Asia and China,

a later form of the Mantranaya, in which the traditions seen in the earlier

Esoteric Buddhism of China and Japan have been overshadowed by the

systems of ritual, meditation and observance whose scriptural authorities

are the texts known as the Yogintantras or Yoganiruttaratantras, later works

that are strongly inuenced by the traditions of the non-Saiddh antika

Saiva

worshippers of Bhairava and the Goddess. The fact that royal initiation

appears as a central element in both these transmissions is strong evidence

of its prevalence in the land that is their common source. It also shows that

it prevailed there throughout the last phase of Indian Buddhism, from the

eighth century onwards.

However the Indian Buddhists adoption and adaptation of

Saiva royal

initiation, and indeed of the many other elements of

Saiva ritualism that

owed into the Mantranaya, should not be seen as an invasion of Buddhism

from the outside. This was a creative and transformative process. The

Buddhists purpose in developing their own Way of Mantras was not merely

to add a repertoire of religious rituals that matched those oered by the

Saivas. They sought to surpass their rivals in the eyes of their patrons

by developing a system of ceremonies that was familiar to the culture

of the courts and oered the same mundane benets of protection and

empowerment of the state and the monarch, but was both more spectacular

and more accessible to potential converts and patrons.

It was more spectacular because it introduced initiation Man

.

d

.

alas on a

larger scale than those of the

Saivas. It was more accessible because it allowed

many more people to be brought before these Man

.

d

.

alas simultaneously and

did not restrict access to those already engaged inBuddhist practice. Chinese,

Japanese and Mongolian evidence shows that this far greater openness to

candidates is found in both the main branches of the transmission of the

Way of Mantras, which indicates that this too, like the practice of royal

initiation itself, derives from Indian usage.

There are already indications of this openness in the Mah avairocan abhi-

sam

.

bodhi, composed probably during the rst second quarter of the seventh

century. But it is most developed and explicit in the Sarvatath agatatattva-

sam

.

graha, a text that developed during the period from the last quarter of

the seventh century into the eighth, and was to have a lasting impact on the

Mantranaya in all its forms.

In this respect the Way of Mantras shows a radical departure from

Saiva

practice. That allowed that

Siva could liberate all kinds of persons through

Man

.

d

.

ala initiation, but it never envisaged opening up the soteriological

process on such a scale. We see here a striking example of the methodological

versatility (up ayakausalam) that Mah ay ana Buddhism made its hallmark.

Adopting the non-Buddhist practice of Man

.

d

.

ala initiation in general and

its royal form in particular it adapted it to its own purpose, turning it into a

spectacular instrument for the propagation of allegiance to the faith among

those elites in India and beyond who might otherwise have seen little reason

to deviate from their established religious traditions.

Alexis Sanderson

All Souls College

University of Oxford

,

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- AbdomenDocument2 pagesAbdomenpranajiNo ratings yet

- Sacred Herbs LongevityDocument1 pageSacred Herbs LongevitypranajiNo ratings yet

- HandDocument2 pagesHandpranajiNo ratings yet

- Chest PtsDocument2 pagesChest PtspranajiNo ratings yet

- Marma Vidya Feb 2016Document1 pageMarma Vidya Feb 2016pranajiNo ratings yet

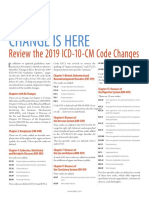

- Icd 10 CM Code Changes White PaperDocument3 pagesIcd 10 CM Code Changes White PaperpranajiNo ratings yet

- Ayurveda: The Mother of Natural Healing: Living Prana Living PranaDocument2 pagesAyurveda: The Mother of Natural Healing: Living Prana Living PranapranajiNo ratings yet

- Facial PtsDocument2 pagesFacial PtspranajiNo ratings yet

- Cranio-Sacraum PTSDocument2 pagesCranio-Sacraum PTSpranajiNo ratings yet

- Quick Tasmpa (Roasted Barley Flour Porridge) Recipe: Modify Ingredients According To Your Dietary Needs/recommendationsDocument1 pageQuick Tasmpa (Roasted Barley Flour Porridge) Recipe: Modify Ingredients According To Your Dietary Needs/recommendationspranajiNo ratings yet

- Jiabs: Journal of The International Association of Buddhist StudiesDocument70 pagesJiabs: Journal of The International Association of Buddhist Studiespranaji100% (1)

- Siddha Tantra Basics v.1Document1 pageSiddha Tantra Basics v.1pranajiNo ratings yet

- Sallie B. King - The Doctrine of Buddha-Nature Is Impeccably BuddhistDocument19 pagesSallie B. King - The Doctrine of Buddha-Nature Is Impeccably BuddhistDhira_100% (1)

- Root Vegetable Broth Recipe for Healthy Homemade StockDocument1 pageRoot Vegetable Broth Recipe for Healthy Homemade StockpranajiNo ratings yet

- Education: 1990-93 1993 - 98 1998 - 2002 2002 - 2010 2004 - Present 2012 - Present 2015 - PresentDocument1 pageEducation: 1990-93 1993 - 98 1998 - 2002 2002 - 2010 2004 - Present 2012 - Present 2015 - PresentpranajiNo ratings yet

- Ont 1 0Document1 pageOnt 1 0pranajiNo ratings yet

- PainDocument40 pagesPainpranajiNo ratings yet

- Mueller Siddha Cranial Workshop 5 2013Document1 pageMueller Siddha Cranial Workshop 5 2013pranajiNo ratings yet

- Resonance - The Basis of Eastern Healing TraditionDocument1 pageResonance - The Basis of Eastern Healing TraditionpranajiNo ratings yet

- VisionArticelMay2007 SleepDocument2 pagesVisionArticelMay2007 SleeppranajiNo ratings yet

- Mueller Siddha Cranial Workshop 5 2013Document1 pageMueller Siddha Cranial Workshop 5 2013pranajiNo ratings yet

- Resonance Estern Healng Traditions PDFDocument1 pageResonance Estern Healng Traditions PDFpranajiNo ratings yet

- Pranic Healing Client FormDocument1 pagePranic Healing Client FormpranajiNo ratings yet

- Breath of Shakti 3 Rishikesh PDFDocument1 pageBreath of Shakti 3 Rishikesh PDFpranajiNo ratings yet

- HollyGuzman Trimesters Cooking Prenatal Qi PDFDocument6 pagesHollyGuzman Trimesters Cooking Prenatal Qi PDFpranaji100% (1)

- Breath of Shakti 3 RishikeshDocument1 pageBreath of Shakti 3 RishikeshpranajiNo ratings yet

- AryaNielsen Gua Sha Research Language IMDocument50 pagesAryaNielsen Gua Sha Research Language IMpranaji100% (1)

- Siddha Cranial WorkDocument2 pagesSiddha Cranial WorkpranajiNo ratings yet

- AryaNielsen Gua Sha Research Language IMDocument11 pagesAryaNielsen Gua Sha Research Language IMpranaji100% (2)

- Pranaji Breath of Shakti RudraDocument1 pagePranaji Breath of Shakti RudrapranajiNo ratings yet