Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Trip To Break One's Heart: Journey To Sierra Leone

Uploaded by

Michael LindenbergerOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Trip To Break One's Heart: Journey To Sierra Leone

Uploaded by

Michael LindenbergerCopyright:

Available Formats

6P

Sunday, April 21, 2013

POINTS

dallasnews.com

The Dallas Morning News

Michael Lindenberger says Sierra Leone is rich in diamonds and, despite the smiles, in misery

REETOWN, Sierra Leone Packed into SUVs, we had bounced and inched and crawled our way through the bush along washed-out roads and rickety bridges until we had arrived at Baomahun, a community of thatched roofs and mud walls 90 miles and seven hours driving from the capital. It was the last Wednesday of March. While the president of Sierra Leone was making headlines in his first visit to the United States at the invitation of the White House, 10 of us from Stanford University were on an unrelated trip to the African country. Barack Obama invited Ernest Bai Koroma to discuss the countrys efforts to increase economic opportunities; we were in Sierra Leone witnessing how much remains to be done. We had arrived four days earlier, with a goal to better understand the lives of some of the poorest people on the planet and to develop a plan to help this sun-basted nation of 5.6 million. This much had been clear before we left: Twelve years after the end of its brutal, diamond-fueled civil war, Sierra Leone remains rich beyond measure in minerals, in diamonds, in gold and, as ever, in misery. A litany of Sierra Leones laments would make Hamlet seem happy. A crowded, chaotic capital city full of slums, of dust and of crumbling buildings and flung-together shanties. Children everywhere, some begging on the streets and others streaming to school on foot amid wild traffic and beeping horns. Women, spread out along the cratered roads walking from before light till after dark, balancing burdens on their heads. In the villages out near the bush, it was worse: Huts without a wall and children without clothes. Disease and desperation hanging in the air like fog. No work, not enough food, and everywhere seething resentment at the foreign mining and agricultural companies whose conflict-ridden deals have pushed farmers and artisanal miners off ancestral lands. We reached Baomahun late that Wednesday to find scores of village chiefs, landowners and others waiting to tell us their stories, something wed grow used to in the days ahead. Told in a handful of languages and in the pain etched in their faces, the tales were as different as one human being from another. But they amounted to the same thing: We are suffering, Baomahun town chief Joseph Karimola told me. In Baomahun, there are 8,000 people but no clean water, no plumbing and no electric power. They are up there enjoying themselves, Karimola told me, indicating the mine complex that has taken their lands but employs only a few villagers. Come sleep here tonight, and you will see. They sleep with electricity, and we sleep here in darkness. How is it that when the land belongs to us, they enjoy themselves and we do not enjoy anything? Thats not a line of questions that likely came up during the White House meeting between Obama and Koroma the next day. Its the kind of complaint that has fallen on deaf ears back in Freetown. Before our trip to the villages, we spent two very long days meeting with top government ministers, and many of them had dismissed villagers complaints as nothing more than greed. In meeting with various company officials, we heard stories of locals who stole fuel from trucks they had been entrusted to drive and of the constant expectation of payments to chiefs and others during endless negotiations. On the other hand, locals told tales of blacklisting, corruption, double-dealing and coercion. ierra Leone is at once one of the least developed nations in the world and one of its most wide-open business opportunities. While signs of the war are everywhere burned-down buildings, broken walls, rapid urbanization it is mending. Koroma, the countrys democratically elected president, just entered his second term. Businesses across the globe are eyeing or upping investments, and its rate of development is among Africas fastest, although it remains near the bottom of the United Nations human development index, at 177th. (The U.S. is third, and Congo and Niger are tied for last at 186th.) Maybe the war did something for us, reflected Alice Foyah, a member of Parliament in the opposition, a woman whose margin of victory during last years elections was among the highest in the country. I think it exposed to the rest of the world an awareness of how enriched we are. Before, when we traveled abroad and returned home, it would just be us getting off the last stop, in Sierra Leone. Now, every plane is loaded with investors coming to our country looking for development. Investors interest alone isnt doing anything for the villagers we ran across. Some get jobs in the mines or on the vast agricultural fields leased by companies eager to supply

Untold wealth, unshared

Michael Lindenberger was part of a fact-finding mission to Sierra Leone. He found that despite grinding poverty, children seemed to smile instantly upon meeting a stranger.

The effects of poverty

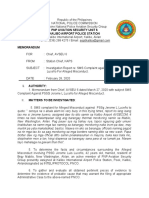

N 50 miles

Guinea

l ke Ro

Makeni Freetown

Sierra Leone

Yawri Bay Bo Kenema

Human development level Low Medium High

Liberia

AFRICA

Detail area

Population: 5.6 million Ofcial language: English Religions:

Muslim 60% Indigenous beliefs 30% 10%

Christian

Year of independence: 1961, from the United Kingdom Government type: Constitutional democracy though outside the capital of Freetown, local chiefs rule for life and exert signicant power.

Under-5 mortality

Probability of dying between birth and exactly age 5, expressed per 1,000 live births.

174 out of 1,000

Life expectancy

Number of years a newborn infant could expect to live

48.1 years

Expected years of schooling

Number of years of schooling that a child of school-entrance age can expect to receive

7.3 years

Poverty

Percentage of the population living below the international poverty line of $1.25 (in purchasing power parity terms) a day.

53.4%

Electricty

Rank by annual electricty generated in kilowatt hours

192 out of 218 countries

omething else has begun flowering, too: There are men and women across the country spending their lives trying to Very high make the country whole again. Some of them EDUCATION* INCOME* HEALTH** have important contacts internationally and are working on a large scale. Others are small New Zealand men, poor people themselves, who have found Qatar Japan tools to bring about change. U.S. I met one such man in the capital, in the offices of Timap for Justice. Thats a nonprofit U.S. group that has trained villagers in the rudiments of law and problem-solving, and called them paralegals. There are 60 of them in 19 offices. They typically solve problems, mediate marital and other disputes, and sometimes work with those accused of crimes to monitor their treatment all without cost. In a nation of only about 200 practicing attorneys, this is U.S. important work. In a crowded Freetown office, I slipped away from my team to run some questions by Harding Sesay, a paralegal for Timap since 2010. Why did he work for Timap? He didnt hesitate. I have a passion, and I have a story, he told me quietly. In my village, my sister was mistreated very, very badly by her husband. We were not able to seek redress because we were poor. I had already learned that in Sierra Leone, seeking justice through the courts has been a rich mans game. Now, Sesay said, he plays a seminal role in changing that reality for villagers who find themselves in a similar position. I am so happy I made this decision, he said. They can see now that they can find justice without worries about the cost. He paused and looked at me before adding, as if this was the all explanation I would ever need: I know the bitterness of not having any money. The look he gave joined other strong visuals that suggest there is more to the country than the misery we saw in the villages. Along the dirt road where a Senegalese company is building a two-lane highway along the coast, for example, real estate lots have been carved out on the opposite hills. Suburban-style housing sits waiting for buyers, expected to be members of the Sierra Leone diaspora still scrambled by the decadelong diamond wars that ended in 2001. The Atlantic Ocean beaches are beautiful and open to the public. Vegetation is lush in places, and, of course, there is wealth waiting in the ground. Its hard to fight an urge to think that, perhaps, Sierra Leones best days are just ahead. It will take a firmer commitment by the men and women running the country to Sierra Leone look after one anothers interests, rather than Sierra No. 174 Leone merely their own, if those better days are No. 177 going to materialize. For now, despite the smiles on many faces, Congo Niger life in Sierra Leone for too many citizens is Sierra nasty, brutish and short. Leone

No. 194 * Data unavailable for some countries ** More nations are represented in the health index than the other two component indexes and the overall index.

The United Nations measures development by combining indexes of education, income and health into a composite human development index (HDI). Sierra Leone is improving since the end of its disastrous civil war in 2001, but has a long way to go. It ranks 177 out of 186 countries in the HDI. Here is how it ranks in each component index.

position of profound weakness. No investor ever sees himself as a humanitarian, one executive of the local government ministry told us. Whenever they see an opportunity to maximize their profits, they will do so. When you are poor, you are disadvantaged. The real disadvantage, advocates for the poor mining and farming villages told us, are citizens without a strong voice in the capital and without a vote on the mining deals. The result is life as Thomas Hobbes might have described it, with the weak always at the mercy of the strong. Certainly, it looks a lot like that to a babyfaced 25-year-old I spoke with. I get up in the morning, and then have nothing, he told me, speaking perfect English. I went to school and tested for the next level. But I had to come home because we could not pay the fees. Now there is no work, no land to farm and I do nothing. These troubling impressions strike a visitor like a punch in the throat, but as the days ticked by, other impressions emerged, too. In the villages and the cities, children seemed to smile instantly upon meeting a stranger. Men tended to offer seats to anyone who looked tired, and even in the midst of the worst poverty, parents prized their children fiercely. Among the children, small kindnesses to one another, like an arm on a shoulder, or a small childs hand held by an older one, popped out of the landscape like flowers in bloom.

bioenergy needs overseas. Most are kept at menial positions and on temporary status, with subsistence pay and zero security. Many more simply have no work at all. National leaders in the governing party told us in meeting after meeting that they

have made large strides in making concession deals with mining and agricultural companies to pay Sierra Leone more for its buried treasures. But most of them, from the attorney general to the deputy speaker of the Parliament, said they continue to negotiate from a

Staff writer Michael Lindenberger is a 2013 John S. Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University. His email address is mlindenberger@ dallasnews.com. This trip was part of a fact-finding mission to Sierra Leone for a project sponsored by the Center for Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law under the guidance of political scientist and professor Jeremy Weinstein of Stanford.

P6 04-21-2013 Set: 17:06:37 Sent by: cstewart@dallasnews.com Opinion CYAN BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Professional Ethics and EtiquetteDocument14 pagesProfessional Ethics and EtiquetteArunshenbaga ManiNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Tresspass To Land As A Civil TortDocument4 pagesTresspass To Land As A Civil TortFaith WanderaNo ratings yet

- Revision ChecklistDocument24 pagesRevision Checklistaditya agarwalNo ratings yet

- Example Business Plan For MicrofinanceDocument38 pagesExample Business Plan For MicrofinanceRh2223db83% (12)

- Mobility Management in Connected Mode (ERAN3.0 - 07)Document359 pagesMobility Management in Connected Mode (ERAN3.0 - 07)Sergio BuonomoNo ratings yet

- HEAVYLIFT MANILA V CADocument2 pagesHEAVYLIFT MANILA V CAbelly08100% (1)

- The Role of Nusantara'S (Indonesian) IN: Legal Thoughts & Practices Globalization of LawDocument175 pagesThe Role of Nusantara'S (Indonesian) IN: Legal Thoughts & Practices Globalization of LawLoraSintaNo ratings yet

- Dallas Morning News March 4 1910Document1 pageDallas Morning News March 4 1910Michael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- For Release July 10, 2017: Carroll Doherty, Jocelyn Kiley, Bridget JohnsonDocument18 pagesFor Release July 10, 2017: Carroll Doherty, Jocelyn Kiley, Bridget JohnsonWorld Religion NewsNo ratings yet

- In The United States District Court For The Southern District of Texas Houston DivisionDocument17 pagesIn The United States District Court For The Southern District of Texas Houston DivisionMichael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- DOJ Sues To Stop AT&T, Time Warner MergerDocument23 pagesDOJ Sues To Stop AT&T, Time Warner MergerCNBC.comNo ratings yet

- White House Comey LettersDocument6 pagesWhite House Comey LettersMichael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- 2016 Tri-Agency ReportDocument27 pages2016 Tri-Agency ReportMichael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- 2017-04-10 Order On Discriminatory IntentDocument10 pages2017-04-10 Order On Discriminatory IntentEddie RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Utilities Motion To Stay CPP 10232015Document52 pagesUtilities Motion To Stay CPP 10232015Michael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- Foundation Prelim Budget 2017-2019 Detailed - UpdatedDocument5 pagesFoundation Prelim Budget 2017-2019 Detailed - UpdatedMichael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- DOJ Report On BPD PDFDocument164 pagesDOJ Report On BPD PDFMichael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- Fair Park Clips (DMN)Document10 pagesFair Park Clips (DMN)Michael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- USPLabs IndictmentDocument35 pagesUSPLabs IndictmentMichael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- HLE A4L Grade HLE A3L Grade PDFDocument1 pageHLE A4L Grade HLE A3L Grade PDFRichardAngelCuencaPachecoNo ratings yet

- Munro, Victoria - Hate Crime in The MediaDocument260 pagesMunro, Victoria - Hate Crime in The MediaMallatNo ratings yet

- Ujian Bulanan 1 2020Document6 pagesUjian Bulanan 1 2020Helmi TarmiziNo ratings yet

- Complaint About A California Judge, Court Commissioner or RefereeDocument1 pageComplaint About A California Judge, Court Commissioner or RefereeSteven MorrisNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet: Magnafloc LT25Document9 pagesSafety Data Sheet: Magnafloc LT25alang_businessNo ratings yet

- Police Power Case Issue Ruling AnalysisDocument10 pagesPolice Power Case Issue Ruling AnalysisCharlene Mae Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Concept of Race 1Document6 pagesConcept of Race 1api-384240816No ratings yet

- Lesson 5-Kartilya NG KatipunanDocument12 pagesLesson 5-Kartilya NG KatipunanKhyla ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- M8 - Digital Commerce IDocument18 pagesM8 - Digital Commerce IAnnisa PutriNo ratings yet

- DPRM Form RSD 03 A Revised 2017Document2 pagesDPRM Form RSD 03 A Revised 2017NARUTO100% (2)

- 2015 LGA Citizens CharterDocument64 pages2015 LGA Citizens CharterErnan BaldomeroNo ratings yet

- PNP Aviation Security Unit 6 Kalibo Airport Police StationDocument3 pagesPNP Aviation Security Unit 6 Kalibo Airport Police StationAngelica Amor Moscoso FerrarisNo ratings yet

- Student Consolidated Oral Reading Profile (English)Document2 pagesStudent Consolidated Oral Reading Profile (English)Angel Nicolin SuymanNo ratings yet

- The Kartilya of The KatipunanDocument2 pagesThe Kartilya of The Katipunanapi-512554181No ratings yet

- Schlage Price Book July 2013Document398 pagesSchlage Price Book July 2013Security Lock DistributorsNo ratings yet

- Safety Abbreviation List - Safety AcronymsDocument17 pagesSafety Abbreviation List - Safety AcronymsSagar GuptaNo ratings yet

- Form ID 1A Copy 2Document3 pagesForm ID 1A Copy 2Paul CNo ratings yet

- GR 199539 2023Document28 pagesGR 199539 2023Gela TemporalNo ratings yet

- Booking Details Fares and Payment: E-Ticket and Tax Invoice - ExpressDocument2 pagesBooking Details Fares and Payment: E-Ticket and Tax Invoice - ExpressWidodo MuisNo ratings yet

- ACC1ILV - Chapter 1 Solutions PDFDocument3 pagesACC1ILV - Chapter 1 Solutions PDFMegan Joye McFaddenNo ratings yet

- HKN MSC - V.24 (Non Well)Document77 pagesHKN MSC - V.24 (Non Well)أحمد خيرالدين عليNo ratings yet

- (CPR) Padilla Vs CA, GR No 121917, 12 March 1997 Case DigestDocument3 pages(CPR) Padilla Vs CA, GR No 121917, 12 March 1997 Case Digestarceo.ezekiel0No ratings yet

- AK Opening StatementDocument1 pageAK Opening StatementPaul Nikko DegolladoNo ratings yet