Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Négritude

Uploaded by

Andrew TandohCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Négritude

Uploaded by

Andrew TandohCopyright:

Available Formats

Ngritude

file:///G:/Ngritude.htm

Ngritude

Ngritude is a cultural movement launched in 1930s Paris by French-speaking black graduate students from France's colonies in Africa and the Caribbean territories. These black intellectuals converged around issues of race identity and black internationalist initiatives to combat French imperialism. They found solidarity in their common ideal of affirming pride in their shared black identity and African heritage, and reclaiming African self-determination, selfreliance, and selfrespect. The Ngritude movement signaled an awakening of race consciousness for blacks in Africa and the African Diaspora. This new race consciousness, rooted in a (re)discovery of the authentic self, sparked a collective condemnation of Western domination, anti-black racism, enslavement, and colonization of black people. It sought to dispel denigrating myths and stereotypes linked to black people, by acknowledging their culture, history, and achievements, as well as reclaiming their contributions to the world and restoring their rightful place within the global community.

The Roots of Ngritude

The movement is deeply rooted in Pan-African congresses, exhibitions, organizations, and publications produced to challenge the theory of race hierarchy and black inferiority developed by philosophers such as Friedrich Hegel and Joseph de Gobineau. Diverse thinkers influenced this rehabilitation process, including anthropologists Leo Frobenius and Maurice Delafosse, who wrote on Africa; colonial administrator Ren Maran, who penned the seminal ethnographic novel Batouala: Vritable roman ngre, an eyewitness account of abuses and injustices within the French colonial system; Andr Breton, the father of Surrealism; French romantics Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire; Haitian Jean-Price Mars, who developed the concept of Indigenism; Haitian anthropologist Antnor Firmin and Cuban Nicols Guilln, who promoted Negrismo. Of major significance are the Harlem Renaissance intellectuals who fled to France to escape racism and segregation in the United States. Prominent among them were Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Richard Wright, and Claude McKay. McKay, who bemoaned divisions of blacks, was acclaimed by Senegalese poet and politician Lopold Sdar Senghor as the spiritual founder of Ngritude values. Senghor argued that "far from seeing in one's blackness inferiority, one accepts it; one lays claim to it with pride; one cultivates it lovingly." Pan-Africanist leader Marcus Garvey similarly implored his peers: "Negroes, teach your children that they are direct descendants of the greatest and proudest race who ever peopled the earth." Back to top

Ngritude's Women

The mobilization of young black women students in Paris signaled the beginning of an international solidarity network among Africans and people of African descent. Martinican students Jane and Paulette Nardal played a primary role in the creation and evolution of Ngritude. Proficient in English, Paulette became a primary cultural intermediary between the Anglophone Harlem Renaissance writers and the Francophone students from Africa and the Caribbean, three of whom would later become the founders of the Ngritude movement: Aim Csaire from Martinique, Lopold Sdar Senghor from Senegal, and Lon-Gontran Damas from French Guiana. Poets and writers, they put their artistry at the service of Ngritude, which soon became a literary movement with ideological, philosophical, and political ramifications. Jane Nardal was credited by her sister as the first "promoter of this movement of ideas so broadly exploited later" by the so-called Trois Pres (Three Fathers), the movement leaders who "took up the ideas tossed out by us and expressed them with more flash and brio... Let's say that we blazed the trail for them." Senghor acknowledged as much in 1960, when he wrote: "We were in contact with these black Americans during the years 192934, through Mademoiselle Paulette Nardal who, with Dr. Sajous, a Haitian, had founded La Revue du monde noir. Mademoiselle Nardal kept a literary salon, where African Negroes, West Indians and American Negroes used to get together." After her death in 1985, Csaire paid tribute to Paulette Nardal as an initiatrice (initiator) of the Ngritude movement and named in her honor a square in Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique. The theoretical and literary body of ideas by Paulette Nardal, Jane Nardal, and another Martinican student, Suzanne Roussi Csaire, usefully outlines Ngritude cultural politics: Jane Nardal's "Internationalisme noir" (Black Internationalism) and "Pantins exotiques" (Exotic Puppets, 1928); Paulette Nardal's "En exil" (In Exile, 1929) and "L'veil de la conscience de race chez les tudiants noirs" (The Awakening of Race Consciousness Among Black Students, 1932); Suzanne Roussi Csaire: "Malaise d'une civilisation (The Malaise of a Civilization, 1942), "Le Grand camouflage" (The Great Camouflage, 1945). The women's writings appeared in periodicals such as the bilingual Revue du monde noir (1931), the radical Lgitime dfense (1932), L'tudiant noir (1934), and later on, the seminal literary review Tropiques (1942), edited by Aim and Suzanne Csaire. Previous publications launched to promote race consciousness and to study black identity included La Voix des ngres, Les Continents (1924), La Race ngre (1927), L'Ouvrier ngre, Ainsi parla l'oncle, La Dpche africaine (1928), Le Cri des ngres, Revue indigne (1931). These publications influenced discussions on race and identity among black Francophone intellectuals and culminated in the founding of Ngritude. Back to top

The Three "Fathers"

The 1931 encounter between Csaire, Senghor, and Damas marks the beginning of a collective exploration of their complex cultural identities as black, African, Antillean, and French. In 1934 they launched the pioneering journal L'tudiant noir (The Black Student), which aimed to break nationalistic barriers among black students in France. Crystallizing diverse expressions of Ngritude by these so-called fathers, L'tudiant noir was its most important political and cultural periodical. While the three leaders agreed on Ngritude's Pan-Africanist engagement to affirm blacks' "beingin-the-world" through literary and artistic expression, they differed in their styles and designs. The term Ngritude (blackness) was coined by Csaire from the pejorative French word ngre. Csaire boldly and proudly incorporated this derogatory term into the name of an ideological movement, and used it for the first time during the writing of his seminal poetic work Cahier d'un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, 1939). In the author's own words, Ngritude is "the simple recognition of the fact that one is black, the acceptance of this fact and of our destiny as blacks, of our history and culture." The concept of Ngritude thus provided a unifying, fighting, and liberating instrument for the black Francophone students in search of their identity. It was an expression of a new humanism that positioned black people within a global community of equals. Back to top

1 of 3

24-Mon,Feb 2014 08:16:PM

Ngritude

file:///G:/Ngritude.htm

Aim Csaire

For Csaire's (19132008), the original concept of Ngritude is rooted in the specificity and unity of black people as historically derived from the Transatlantic Slave Trade and their plight in New World plantation systems. In his own words, "Ngritude [is] not a cephalic index, or plasma, or soma, but measured by the compass of suffering." The movement was born of a shared experience of discrimination, oppression, and subordination to be suppressed through concerted efforts of racial affirmation. Csaire's response to the centuries-old alienation of blacks is a call to reject assimilation and reclaim their own racial heritage and qualities. He experiences his ngritude as a fact, a revolt, and the acceptance of responsibility for the destiny of his race. He advocates the emergence of "cultural workers" who will reveal black specificity to the world by articulating their experiences, their fortunes and misfortunes. This consciousness of blacks' "being-in-the-world" will write them back into history and validate their achievements. It will restore the lost humanity, dignity, integrity, and subjectivity of black identity, necessary to confront colonialism, racism, and Western imperialism. He rejects assimilation and articulates the concept in his Cahier d'un retour au pays natal: My Ngritude is not a stone, its deafness hurled againstthe clamor of the day my Ngritude is not a leukoma of dead liquid over the earth'sdead eye my Ngritude is neither tower nor cathedral it takes root in the red flesh of the soil it takes root in the ardent flesh of the sky it breaks through opaque prostration with its upright patience. In other words, black personality is not the lifeless object society has reduced it to; instead, it is a vibrant creative force that confronts racism, colonialism, and other forms of domination. Some of Csaire's numerous works are Les Armes miraculeuses, Et Les Chiens se taisaient (1946), Soleil cou-coup (1948), Corps perdu (1950), Discours sur le colonialisme (1955), Lettre Maurice Thorez (1956), La Tragdie du roi Christophe (1963), Une Saison au Congo (1966), Une Tempte (1968), Moi, laminaire (1982). Back to top

Lon-Gontran Damas

Damas (19121978) was the first of the Trois Pres to publish his own book of poems, Pigments (1937), which underscores the need to cure the ills of Western society and is sometimes referred to as the "manifesto of the movement." Its style and overtones passionately condemn racial division, slavery, and colonialist assimilation. For Damas, Ngritude is a categorical rejection of an assimilation that negated black spontaneity as well as a defense for his condition as black and Guyanese. Becoming French requires loss, repression, and rejection of self as well as adoption of a civilization that robs indigenous cultures, values, and beliefs, as articulated in his poem "Limb" in which the poet laments his losses: Give me back my black dolls so that I may play with them the nave games of my instinct in the darkness of its laws once I have recovered my courage and my audacity and become myself once more Damas's poetry is influenced by elements of African oral traditions and Caribbean calypso, rhythms and tunes of African-American blues and jazz, Harlem Renaissance poetry, as well as French Surrealist ideas.Damas's subsequent works are Retour de Guyane (1938), Pomes ngres sur des airs africains (1948), Graffiti (1952), Black-Label (1956), Nvralgies (1965), and Veilles noires (1943). Back to top

Lopold Sdar Senghor

Like Csaire and Damas, Senghor (19062001) promotes a quest for the authentic self, knowledge of self, and a rediscovery of African beliefs, values, institutions, and civilizations. Unlike his two peers, who strongly oppose assimilation, Senghor advocates assimilation that allows association, "a cultural mtissage" of blackness and whiteness. He posits notions of a distinct Negro soul, intuition, irrationalism, and crossbreeding to rehabilitate Africa and establish his theory of black humanism. He envisions Western reason and Negro soul as instruments of research to create "une Civilisation de l'Universel, une Civilisation de l'Unit par symbiose" (a Civilization of the Universal, a Civilization of Unity by Symbiosis). For Senghor, the dual black and white cultural background gives insights that neither can give separately, and African input can help solve some problems that have challenged Westerners. He points to a new race consciousness that lays the foundation for challenging enslavement and colonization of blacks, as well as establishing a "rendez du donner et recevoir" (give-and-take). To the charge that Ngritude is racist, Senghor responds with his definition, "Ngritude... is neither racialism nor self-negation. Yet it is not just affirmation; it is rooting oneself in oneself, and self-confirmation: confirmation of one's being. It is nothing more or less than what some Englishspeaking Africans have called the African personality." Ngritude must take its place in contemporary humanism in order to enable black Africa to make its contribution to the "Civilization of the Universal," which is so necessary in our divided but interdependent world. Senghor's poems such as "Joal," which captures cultural memories of his childhood and ancestral lands, are interspersed with anti-colonialist rage. Others make an appeal for reconciliation and God's forgiveness for France's dehumanization of blacks through enslavement and colonization. Senghor's influence and example were very important in encouraging African intellectuals to devote themselves to literature, poetry, and the arts. Some major works by Senghor are Chants d'ombre (1945), Hosties noires, Anthologie de la nouvelle posie ngre et malgache (1948), Libert I: Ngritude et humanisme (1964), Libert II: Nation et voies africaines du socialisme (1971), Libert III: Ngritude et civilisation de l'universel (1977), Ce que je crois (1988). In 1947, a fellow Senegalese, Alioune Diop, founded the seminal literary magazine, Prsence Africaine, to disseminate ideas of Ngritude and to promote other black writers. The review --and later the publishing house--earned the support of progressive French intellectuals such as Pablo Picasso, Andr Breton, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre. It helped to position black writers in mainstream French literary circles. Back to top

2 of 3

24-Mon,Feb 2014 08:16:PM

Ngritude

file:///G:/Ngritude.htm

Ngritude Sympathizers and Critics

In a preface to Senghor's Anthologie de la nouvelle posie ngre et malgache, titled "Orphe noir" French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre appears as both critic and sympathizer. He calls Ngritude an "anti-racist racism" but also introduces it into mainstream French literature and validates it as a philosophy of existence. Another critic of the concept was Ren Mnil, a Marxist philosopher and co-founder of Martinican cultural review Tropiques, with Aim and Suzanne Csaire. He considered Ngritude a form of black exoticism and self-consciousness sustaining French imperialism. Guadeloupean scholar Maryse Cond has credited Ngritude with the birth of French Caribbean literature, but she has also critiqued its fetishization of blackness and black identity politics, as well as black Antilleans' idea of a return to Africa. Senghor's existentialist definition of Ngritude was challenged by African philosophers and scholars such as Marcien Towa (Essai sur la problmatique philosophique dans l'Afrique actuelle, 1971), Stanislas Adotevi (Ngritude et ngrologues, 1972), and Paulin Hountondji (Sur la philosophie africaine, 1977.) A revolutionary theoretician, psychiatrist, and former student of Csaire's, Frantz Fanon dismissed the concept of Ngritude as too simplistic and claimed in his 1952 book Peau noire, masques blancs that the notion of the "black soul was but a white artifact." A major critic of the movement was Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka, who viewed Ngritude as reinforcing colonial ideology, a stance that automatically placed black intellectuals on the defensive. For him, "The tiger does not proclaim its tigerness, it jumps on its prey." Back to top

Ngritude and Beyond

Numerous Francophone African writers contributed to Ngritude literature as they produced works focused on the plight of their peopleamong them Mongo Beti, David Diop, Birago Diop, Cheikh Hamidou Kane, Paul Niger, Sembne Ousmane, and Guy Tirolien. The 1970s signaled a shift in style, with works by writers such as Ahmadou Kourouma, of Cte d'Ivoire, who introduced his native Malinke linguistic features into French. Younger generations of writers are creating a new type of language that draws the reader into African daily life. Cases in point are Congolese Daniel Biyaoula's Alley Without Exit, Mauritian Carl de Souza's The House Walking Towards the Ocean, or Cameroonian Calixte Beyala's The Lost Honors. Their literature claims creative uses and adaptations of the French language to African realities. In the French Antilles, the concept of Ngritude has been expanded into Antillanit by writer douard Glissant (Caribbean Discourse 1981). He promotes an opening of black experience to a global culture toward a liberating end. A new generation of Caribbean writers, including Patrick Chamoiseau, Raphal Confiant, and Jean Bernab, reclaim Crolitthe plural genealogy and multiple identity of Antillean culture, with its African, Amerindian, Chinese, Indian, and French ethnic components (loge de la Crolit (In Praise of Creoleness; Traverse Paradoxale du Sicle). The proponents of the Crolit movement aim to portray Caribbean identity and reality by creating a new adapted language within the Creole oral aesthetics and tradition, without violating the rules of correct French rhetoric. The concept of Ngritude is a defining milestone in the rehabilitation of Africa and African diasporic identity and dignity. It is a driving inspiration behind the current flowering of literature by black Francophone writers. Alongside other Pan-African movements such as the Harlem Renaissance, Garveyism, and Negrismo, Ngritude has contributed to writing Africa and its achievements back into history, as well as fostering solidarity among Africans and people of African descent. Back to top

Bibliography

Csaire, Aim. Notebook of a Return to the Native Land. Trans. Clayton Eshleman and Annette Smith, 1947. Damas, Lon Gontran. Pigments. Paris: Guy Lvis Mano, 1937. Edwards, Brent Hayes. The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation and the Rise of Black Internationalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003, pp. 11985. Kesteloot, Lilyan. Black Writers in French: A Literary History of Negritude. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1991. . Black Writers in French: A Literary History of Negritude. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1991. Senghor, Leopold S. Anthologie de la nouvelle posie ngre et malgache de langue franaise. Paris : Presses universitaires de France, 1948. . The Collected Poetry, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991. Sharpley-Whiting, T. Denean. Negritude Women. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002. Hymans, Jacques Louis. Leopold Sedar Senghor: An Intellectual Biography. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1971. Warner, Keith Q. ed. Critical Perspectives on Leon Gontran Damas. Boulder: Three Continents Press, 1988.

3 of 3

24-Mon,Feb 2014 08:16:PM

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Adinkra SymbolsDocument26 pagesAdinkra Symbolsextinguisha4real100% (2)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- 1 Prayer CycleDocument4 pages1 Prayer CycleKingSovereign100% (4)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Argument Writing TemplateDocument3 pagesArgument Writing TemplateSiti IlyanaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- H. P. Lovecraft: Trends in ScholarshipDocument18 pagesH. P. Lovecraft: Trends in ScholarshipfernandoNo ratings yet

- New Church Monthly Report: Reporting Month: - YearDocument2 pagesNew Church Monthly Report: Reporting Month: - YearAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Grossman ModelDocument32 pagesGrossman ModelAndrew Tandoh100% (2)

- Oracle 11g Murali Naresh TechnologyDocument127 pagesOracle 11g Murali Naresh Technologysaket123india83% (12)

- 10 - Sampling and Sample Size Calculation 2009 Revised NJF - WBDocument41 pages10 - Sampling and Sample Size Calculation 2009 Revised NJF - WBObodai MannyNo ratings yet

- Eliminating Duplicate Cases Stat ADocument2 pagesEliminating Duplicate Cases Stat AAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter 2Document46 pages09 Chapter 2Andrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Example How To Write A ProposalDocument9 pagesExample How To Write A ProposalSpoorthi PoojariNo ratings yet

- MSC Thesis SupervisionDocument1 pageMSC Thesis SupervisionAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Minimum Capital Requirement GhanaDocument2 pagesMinimum Capital Requirement GhanaAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Banking Sector Report Highlights Ghana Bank PerformanceDocument18 pagesBanking Sector Report Highlights Ghana Bank PerformanceAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Identifying at Risk Students With SPQDocument8 pagesIdentifying at Risk Students With SPQAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Bank Regulation and Supervision Around The World 15JAN2013Document111 pagesBank Regulation and Supervision Around The World 15JAN2013Andrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Legal and Regulatory FrameworkDocument2 pagesLegal and Regulatory FrameworkAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Durbin-Watson Test for AutocorrelationDocument6 pagesDurbin-Watson Test for AutocorrelationAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Dividend Policy On Commercial Banks Performance in GhanaDocument12 pagesThe Impact of Dividend Policy On Commercial Banks Performance in GhanaAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Omitted Variable TestsDocument4 pagesOmitted Variable TestsAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Timetable For The Spring Semester 2013, Odense PDFDocument3 pagesTimetable For The Spring Semester 2013, Odense PDFAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Thyristor - Cross ReferenceDocument13 pagesThyristor - Cross Referencerachmanjkt100% (2)

- SSRN Id2191280 1Document21 pagesSSRN Id2191280 1Andrew TandohNo ratings yet

- All Saints, Stranton Church Hartlepool: Annual Report of The Parochial Church Council For The Year Ended 31 December 2013Document18 pagesAll Saints, Stranton Church Hartlepool: Annual Report of The Parochial Church Council For The Year Ended 31 December 2013Andrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Test PDFDocument1 pageTest PDFAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Dividend Policy On Commercial Banks Performance in GhanaDocument14 pagesThe Impact of Dividend Policy On Commercial Banks Performance in GhanaAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- GeometryDocument4 pagesGeometryAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Cover Page ETHICS and The Conduct of Business 3rdDocument1 pageCover Page ETHICS and The Conduct of Business 3rdAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- The Use of Dummy Variables in Regression AnalysisDocument2 pagesThe Use of Dummy Variables in Regression Analysisbrose5No ratings yet

- 2014wesp Country Classification (Document8 pages2014wesp Country Classification (Tanveer AhmadNo ratings yet

- Xtxttobit 2Document8 pagesXtxttobit 2Andrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Keynes ConsumptionDocument9 pagesKeynes ConsumptionAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Sample - Employment LetterDocument2 pagesSample - Employment LetterAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- 1 cm Graph Paper with Red LinesDocument1 page1 cm Graph Paper with Red LinesAndrew TandohNo ratings yet

- Standby Practical NotesDocument15 pagesStandby Practical NotesMohan KumarNo ratings yet

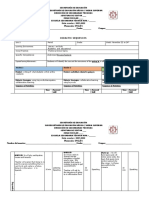

- Parang Foundation College Inc.: Course No. Descriptive Title Degree Program/ Year Level InstructressDocument4 pagesParang Foundation College Inc.: Course No. Descriptive Title Degree Program/ Year Level InstructressShainah Melicano SanchezNo ratings yet

- 26 The Participles: 272 The Present (Or Active) ParticipleDocument7 pages26 The Participles: 272 The Present (Or Active) ParticipleCerasela Iuliana PienoiuNo ratings yet

- "Building A Data Warehouse": Name: Hanar Ahmed Star Second Stage C2 (2019-2020)Document5 pages"Building A Data Warehouse": Name: Hanar Ahmed Star Second Stage C2 (2019-2020)Hanar AhmedNo ratings yet

- Câu CH Đ NG) : Teachero English Center 0936.821.022 Unit 3: Teen Stress and Pressure Practice Exercise 1 & 2Document6 pagesCâu CH Đ NG) : Teachero English Center 0936.821.022 Unit 3: Teen Stress and Pressure Practice Exercise 1 & 2Harley NguyenNo ratings yet

- Going to PlanDocument5 pagesGoing to PlanBeba BbisNo ratings yet

- 2015 Smo BookletDocument16 pages2015 Smo BookletMartin Martin MartinNo ratings yet

- آسان قرآنی عربی کورسDocument152 pagesآسان قرآنی عربی کورسHira AzharNo ratings yet

- Chaly Ao - by Javad SattarDocument117 pagesChaly Ao - by Javad SattarJavad SattarNo ratings yet

- M18 - Communication À Des Fins Professionnelles en Anglais - HT-TSGHDocument89 pagesM18 - Communication À Des Fins Professionnelles en Anglais - HT-TSGHIbrahim Ibrahim RabbajNo ratings yet

- Parasmai Atmane PadaniDocument5 pagesParasmai Atmane PadaniNagaraj VenkatNo ratings yet

- Understand Categorical SyllogismsDocument13 pagesUnderstand Categorical SyllogismsRizielle Mendoza0% (1)

- Peace at Home, Peace in The World.": M. Kemal AtatürkDocument12 pagesPeace at Home, Peace in The World.": M. Kemal AtatürkAbdussalam NadirNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For Fundamentals of The Embedded Systems: Programming ExamplesDocument3 pagesSyllabus For Fundamentals of The Embedded Systems: Programming ExamplesvarshaNo ratings yet

- SGK Ielts 4-5.0Document174 pagesSGK Ielts 4-5.0Nguyệt Nguyễn MinhNo ratings yet

- The strange looking bus that could replace 40 conventional busesDocument1 pageThe strange looking bus that could replace 40 conventional busesJoseline MorochoNo ratings yet

- Lab 3 - Operations On SignalsDocument8 pagesLab 3 - Operations On Signalsziafat shehzadNo ratings yet

- SECRET KNOCK PATTERN DOOR LOCKDocument5 pagesSECRET KNOCK PATTERN DOOR LOCKMuhammad RizaNo ratings yet

- Job ApplicationDocument15 pagesJob ApplicationЮлияNo ratings yet

- LISTENING COMPREHENSION TEST TYPESDocument15 pagesLISTENING COMPREHENSION TEST TYPESMuhammad AldinNo ratings yet

- Thomas Nagel CVDocument12 pagesThomas Nagel CVRafaelRocaNo ratings yet

- CS302P - Sample PaperDocument10 pagesCS302P - Sample PaperMian GNo ratings yet

- 3 Unit 6 Week 5 Lesson Plan PlaybookDocument18 pages3 Unit 6 Week 5 Lesson Plan PlaybookembryjdNo ratings yet

- WM LT01 Manual TransferDocument9 pagesWM LT01 Manual TransferswaroopcharmiNo ratings yet

- تطبيق أركون للمنهج النقدي في قراءة النص القرآني سورة التوبة أنموذجاDocument25 pagesتطبيق أركون للمنهج النقدي في قراءة النص القرآني سورة التوبة أنموذجاLok NsakNo ratings yet

- Authorization framework overviewDocument10 pagesAuthorization framework overviewNagendran RajendranNo ratings yet