Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2013

Uploaded by

abossoneOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2013

Uploaded by

abossoneCopyright:

Available Formats

KEY FACTS

w Global military expenditure

was $1747billion in 2013.

w Total spending fell by 1.9 per

cent in real terms between 2012

and 2013. This was the second

consecutive year in which

spending fell.

w Military spending fell in the

WestNorth America, Western

and Central Europe, and

Oceaniawhile it increased in

all other regions.

w The ve biggest spenders in

2013 were the United States,

China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and

France.

w Military spending by the USA

fell by 7.8per cent, to

$640billion. A large part of the

fall can be attributed to the

reduction in spending on

overseas military oper ations.

w Chinas spending increased

by 7.4 per cent, representing a

long-term policy of rising

military spending in line with

economic growth.

w Russias military spending

increased by 4.8per cent, and

for the rst time since 2003 it

spent a bigger share of its GDP

on the military than the USA.

w Saudi Arabia was the fourth

biggest spender in 2013, having

ranked seventh in 2012. The

United Kingdom has now fallen

to sixth place.

w A total of 23 countries

doubled their military spending

in real terms between 2004 and

2013. These countries are in all

regions of the world apart from

North America, Western and

Central Europe, and Oceania.

SIPRI Fact Sheet

April 2014

TRENDS IN WORLD MILITARY

EXPENDITURE, 2013

sam perlo-freeman and carina solmirano

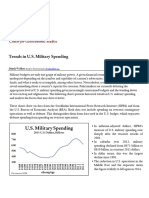

Global military expenditure fell in 2013, by 1.9per cent in real terms, to reach

$1747billion. This was the second consecutive year in which spending fell,

and the rate of decrease was higher than the 0.4 per cent fall in 2012 (see

gure1).

A pattern has been established in recent years whereby military spend-

ing has fallen in the Westthat is, in North America, Western and Central

Europe, and Oceaniawhile it has increased in other regions. This tendency

was even more pronounced in 2013, with military spending increasing in

every region and subregion outside the West. In fact, the total for the world

excluding just one countrythe United Statesincreased by 1.8 per cent in

2013, despite falls in Europe and elsewhere.

From 14 April 2014 the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database includes

newly released information on military expenditure in 2013. This Fact Sheet

describes the global, regional and national trends in military expenditure

that are revealed by the new data, with a special focus on those countries that

have more than doubled their military spending over the period 200413.

M

i

l

i

t

a

r

y

e

x

p

e

n

d

i

t

u

r

e

(

c

o

n

s

t

a

n

t

U

S

$

b

i

l

l

i

o

n

)

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2

0

1

3

2

0

1

2

2

0

1

1

2

0

1

0

2

0

0

9

2

0

0

8

2

0

0

7

2

0

0

6

2

0

0

5

2

0

0

4

2

0

0

3

2

0

0

2

2

0

0

1

2

0

0

0

1

9

9

9

1

9

9

8

1

9

9

7

1

9

9

6

1

9

9

5

1

9

9

4

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

2

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

0

1

9

8

9

1

9

8

8

Figure 1. World military expenditure, 19882013

Note: The totals are based on the data on 172 states in the SIPRI Military Expenditure

Database, <http://www.sipri.org/databases/milex/>. The absence of data for the Soviet

Union in 1991 means that no total can be calculated for that year.

2 sipri fact sheet

THE TOP 15 MILITARY SPENDERS

IN 2013

There was only one change in the list of

countries comprising the worlds top 15

military spenders in 2013, with Canada

dropping out, to be replaced by Turkey (see

table1). There were also several changes in

order. Most notably, Saudi Arabia climbed

from seventh to fourth place, having

increased its military spending by 14 per

cent in 2013. Among the lar gest spenders,

Saudi Arabia has by far the highest mili-

tary burdenthat is, military spending

as a share of GDP. At 9.3 per cent, it is also

the second highest (after Oman) for any

country for which SIPRI has recent data.

Along with Saudi Arabias rise, the United

Kingdom has fallen out of the top 5 spend-

ers, although revised gures for 2011 and

2012 show that the UK had already fallen

to sixth place then, probably for the rst

time since World War II.

Military spending by the USA declined

by 7.8 per cent in real terms in 2013, to

$640billion. A part of the fall ($20billion

of the $44 billion nominal fall) can be

attributed to the reduction in outlays for

Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO)

that is, overseas military oper ations,

chiey in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Chinas spending increased by 7.4 per cent in real

terms. While China has been behaving more asser-

tively in recent years in territorial disputes with

Japan in the East China Sea, and with the Philippines

and Viet Nam in the South China Sea, these height-

ened tensions do not seem to have changed the trend

in Chinese military spending, which represents a

long-term policy of rising military spending in line

with economic growth.

Russias spending increased by 4.8per cent in real

terms, and its military burden exceeded that of the

USA for the rst time since 2003. Russias spend-

ing has risen as it continues to implement the State

Armaments Plan for 201120, under which it plans to

spend 20.7 trillion roubles ($705 billion) on new and

upgraded armaments. The goal is to replace 70 per

cent of equipment with modern weapons by 2020.

While South Korea and Turkey also increased

their spending, military spending fell in France, the

Table 1. The 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2013

Spending gures are in US$, at current prices and exchange rates. Figures for

changes are calculated from spending gures in constant (2012) prices.

Rank

Country

Spending,

2013 ($b.)

Change,

200413

(%)

Spending as a

share of GDP (%)

a

2013 2012 2013 2004

1 1 USA 640 12 3.8 3.9

2 2 China [188] 170 [2.0] [2.1]

3 3 Russia [87.8] 108 [4.1] [3.5]

4 7 Saudi Arabia 67.0 118 9.3 8.1

5 4 France 61.2 -6.4 2.2 2.6

6 6 UK 57.9 -2.5 2.3 2.4

7 9 Germany 48.8 3.8 1.4 1.4

8 5 Japan 48.6 -0.2 1.0 1.0

9 8 India 47.4 45 2.5 2.8

10 12 South Korea 33.9 42 2.8 2.5

11 11 Italy 32.7 -26 1.6 2.0

12 10 Brazil 31.5 48 1.4 1.5

13 13 Australia 24.0 19 1.6 1.8

14 16 Turkey 19.1 13 2.3 2.8

15 15 UAE

b

[19.0] 85 4.7 4.7

Total top 15 1 408

World total 1 747 26 2.4 2.4

[ ] = SIPRI estimate.

a

The gures for military expenditure as a share of gross domestic product

(GDP) are based on data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) World

Economic Outlook database, Oct. 2013.

b

Data for the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is for 2012, as gures for 2013 are

not available.

N

e

a

r

l

y

f

o

u

r

-

f

if

t

h

s

o

f a

ll m

ilitary expenditure in 201

3

w

a

s

m

a

d

e

b

y

1

5

s

t

a

t

e

s

USA, 37%

Others, 21%

U

A

E

,

1

.

1

%

T

u

r

k

e

y

,

1

.

1

%

A

u

s

t

r

a

l

i

a

,

1

.

4

%

B

r

a

z

i

l

,

1

.

8

%

I

t

a

l

y

,

1

.

9

%

S

o

u

t

h

K

o

r

e

a

, 1

.9

%

In

d

ia

, 2

.7

%

Ja

p

a

n

, 2

.8

%

Germany, 2.8%

UK, 3.3%

France, 3.5%

Saudi Arabia, 3.8%

Russia, 5.0%

China,

11%

J

u

s

t

2

s

t

a

t

e

s

m

a

d

e

n

e

a

r

l

y

h

a

l

f

o

f

a

l

l

m

ilit

a

r

y

e

xp

enditure

Figure 2. The share of world military expenditure of the

15states with the highest expenditure in 2013

trends in world military expenditure, 2013 3

UK, Italy, Brazil, Australia and Canada,

as well as the USA. Spending by Ger-

many, Japan and India was essentially

unchanged. For much of the 2000s,

military spending increased fairly

rapidly in Brazil and India (as it did

in fellow BRIC countries Russia and

China). However, since 200910 these

increases have stopped or gone slightly

into reverse, as economic growth has

weakened and spending on other sectors

has taken priority.

REGIONAL TRENDS

While spending in North America and Western and Central Europe fell in

2013, it increased in all other regions (see gure3). The largest increase was

in Africa, by 8.3 per cent.

Western and Central Europe

In Western and Central Europe, a majority of countries continued to cut mil-

itary spending as austerity policies were maintained in most of the region.

The falls in the region since the beginning of the nancial

and economic crisis in 2008 are no longer conned to Cen-

tral Europe and the crisis countries of Western Europe

(see table 2). Falls of over 10 per cent in real terms since

2008 have now been recorded in Austria, Belgium, Greece,

Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and the UK, as well as

all countries in Central Europe except Poland. In contrast,

Germanys military spending was 2per cent higher.

France, despite continuing weak economic growth, has

largely maintained its military spending during the global

economic crisis, and spending in 2013 was just 4 per cent

lower than in 2008. This trend is likely to continue, follow-

ing the adoption in 2013 of the Military Programming Law

for the period 201419. The law sets the total defence budget,

excluding military pensions, at 190 billion ($252 billion)

over 6 years (at 2013 prices). The budgets for 201416 are

planned to be 31.4billion ($41.7 billion) each year in current

prices, implying a slight fall in real terms. Long-term plans

for the period to 2025 laid out in the April 2013 Defence and

Secur ity White Paper suggest a subsequent stabilization in

real terms.

Latin America

Military expenditure in Latin America increased by 2.2 per cent in real

terms in 2013 and by 61 per cent between 2004 and 2013 (see table 3). In

contrast to previous years, the rate of increase of military spending in South

Change in military expenditure (%)

8 6 4 2 0 2 4 6 8 10

Middle East

Western and Central Europe

Eastern Europe

Oceania

South East Asia

East Asia

Central and South Asia

Latin America

North America

Sub-Saharan Africa

North Africa

World

Figure 3. Changes in military expenditure, by region, 201213

Table 2. Military expenditure in Europe

Spending,

2013 ($b.)

Change (%)

201213 200413

Europe 410 -0.7 7.6

Eastern Europe 98.5 5.3 112

Western and

Central Europe

312 -2.4 -6.5

Major changes, 201213

Major increases % Major decreases %

Ukraine 16 Spain -13

Belarus 15 Albania -13

Latvia 9.3 Hungary -12

Switzerland 9.0 Netherlands -8.3

4 sipri fact sheet

America has slowed down, primarily due to Brazil, the larg-

est spender in the region, decreasing military spending by

3.9 per cent in 2013. Brazilian military spending had been

increasing rapidly, by over 7 per cent per year between 2003

and 2010, but it peaked in 2010.

In Central America and the Caribbean, military spending

continued to grow rapidly, especially in Honduras (22 per

cent), Nicaragua (18 per cent) and Guatemala (11 per cent), in

the wake of continuing drug cartel-related violence. Mexico

also increased spending by 5.1 per cent, despite weaker eco-

nomic growth.

Africa

Africa had the largest relative rise in military spending in

2013 of any region, by 8.3 per cent, to reach $44.9 billion (see

table4). While the regional trend tends to be dominated by

a few key countries, military spending rose in two-thirds of the countries for

which data is available.

Ghana more than doubled its military spending in 2013, from $109 million

in 2012 to $306 million in 2013. This does not include funds from donors,

which totalled $47 million in 2013. According to the budget statement, the

budget will allow continued modernization of the armed forces, which are

heavily involved in international peacekeeping operations.

Despite the huge increase, Ghanas military burden in 2013

is projected to be only 0.6 per cent of GDP.

Algeria continued the breakneck pace of growth in its

military spending, with an 8.8 per cent increase in 2013, to

reach $10.4 billionthe rst time an African country has

spent more than $10 billion on its military. The reasons

for Algerias ongoing militarization include its desire for

regional power status, the powerful role of the military, the

threat of terrorismincluding from armed Islamist groups

in neighbouring Maliand the ready availability of oil

funds.

Another country where oil wealth is supporting increased

military spending is Angola, which became the second

largest military spender in Africaand the largest in sub-

Saharan Africain 2013, with an increase of 36 per cent in

2013 (and 175 per cent since 2004), to reach $6.1 billion. This

is the rst time that Angolas spending has surpassed that of

South Africa, which spent $4.1 billion in 2013, an increase of 17 per cent since

2004. Angola and Algeria both now have military burdens of 4.8 per cent of

GDP, the highest in Africa for countries where recent data is available.

Asia and Oceania

Military expenditure in Asia and Oceania increased by 3.6per cent in 2013,

to reach $407 billion. Asia and Oceania is the only region where spending has

Table 3. Military expenditure in the Americas

Spending,

2013 ($b.)

Change (%)

201213 200413

Americas 736 -6.8 16

Central America

and Caribbean

9.6 6.0 94

North America 657 -7.8 12

South America 67.4 1.6 58

Major changes, 201213

Major increases % Major decreases %

Paraguay 33 Jamaica -9.0

Honduras 22 United States -7.8

Nicaragua 18 El Salvador -4.5

Colombia 13 Brazil -3.9

Table 4. Military expenditure in Africa

Spending,

2013 ($b.)

Change (%)

201213 200413

Africa (44.9) 8.3 81

North Africa (18.7) 9.6 137

Sub-Saharan

Africa

(26.2) 7.3 55

Major changes, 201213

Major increases % Major decreases %

Ghana 129 Madagascar -25

Angola 36 Botswana -7.5

Congo, Dem. Rep. 34 Uganda -7.0

Zambia 15 Nigeria -5.1

( ) = uncertain estimate.

trends in world military expenditure, 2013 5

increased in every year since the beginning of the current

consistent series of SIPRI data in 1988.

Most of the increase in the region in 2013 was due to a

7.4 per cent increase by China; excluding China, spending

in the rest of the region increased by just 0.9 per cent. This

gure is however made up of a variety of increases and

decreases in diferent countries (see table5). While military

spending fell in Oceania (chiey Australia), it increased in

Central and South Asia and in East Asia, although the latter

increase was almost entirely due to China.

In particular, military expenditure in South East Asia rose

by 5.0 per cent, led by increases in Indonesia, the Philip-

pines and Viet Nam, the latter two prompted to a signicant

extent by tensions with China over territorial disputes in

the South China Sea.

The Middle East

Military expenditure in the Middle East increased by 4 per cent in real

terms in 2013 and 56 per cent between 2004 and 2013, to reach an esti-

mated $150 billion (see table 6). While gures for military expenditure in

the Middle East have traditionally been very uncertain, the lack of data has

worsened recently. In 2013, there was no available data for Iran, Qatar, Syria,

the United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

The largest increases in military spending were in Iraq (27 per cent)

and Bahrain (26 per cent). It is likely that increases in defence spending in

Bahrain are related to recent purchases of arms used to suppress domestic

unrest as well as to troubled relations with neighbouring Iran. In Iraq,

recent increases are aimed at building the capacity and armaments of the

Iraqi armed forces, in order to improve the security of citi-

zens, access to services and protection of oil production and

exports.

Saudi Arabia, the largest spender in the region, increased

spending by 14per cent to a total of $67.0 billion in 2013.

In Oman, in contrast, military expenditure fell by 27 per

cent compared to 2012, but it was still 31 per cent higher

than in 2011. This is the result of large supplementary

budgets in both 2012 and 2013, representing a one-of major

increase for equipment modernization and staf expansion.

Oman has the largest military burden in the Middle East, at

11.3per cent of GDP in 2013.

THE BIGGEST INCREASES IN MILITARY SPENDING, 200413

A total of 23 countries have doubled their military spending in real terms

since 2004 (excluding countries that spent less than $100 million in 2013

see gure 4). What is striking about these countries is their diversity and the

variety of reasons behind their increases, where a reason can be discerned.

The countries are in all regions and subregions apart from North America,

Western and Central Europe, and Oceania.

Table 5. Military expenditure in Asia and Oceania

Spending,

2013 ($b.)

Change (%)

201213 200413

Asia and Oceania 407 3.6 62

Central and South

Asia

63.7 1.2 49

East Asia 282 4.7 74

Oceania 25.9 -3.2 19

South East Asia 35.9 5.0 47

Major changes, 201213

Major increases % Major decreases %

Afghanistan 77 Timor-Leste -12

Philippines 17 Australia -3.6

Sri Lanka 12 Taiwan -2.6

Kazakhstan 10

Table 6. Military expenditure in the Middle East

Spending,

2013 ($b.)

Change (%)

201213 200413

Middle East (150) 4.0 56

Major changes, 201213

Major increases % Major decreases %

Iraq 27 Oman -27

Bahrain 26 Yemen -12

Saudi Arabia 14 Jordan -9.4

( ) = uncertain estimate.

6 sipri fact sheet

H

o

n

d

u

r

a

s

$

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

2

3

0

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

3

7

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

4

0

S

w

a

z

i

l

a

n

d

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

1

1

2

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

1

1

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

1

3

C

a

m

b

o

d

i

a

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

2

4

3

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

0

5

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

9

3

G

h

a

n

a

$

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

3

0

6

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

2

4

3

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

9

5

A

r

m

e

n

i

a

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

4

2

7

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

1

5

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

2

9

G

e

o

r

g

i

a

$

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

4

4

3

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

2

3

0

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

6

4

A

f

g

h

a

n

i

s

t

a

n

$

$

$

$

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

1

2

9

3

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

5

5

7

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

1

2

3

P

a

r

a

g

u

a

y

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

4

7

7

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

2

7

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

5

0

N

a

m

i

b

i

a

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

3

9

6

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

0

8

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

4

6

B

e

l

a

r

u

s

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

9

6

5

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

4

6

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

7

0

B

a

h

r

a

i

n

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

1

2

3

6

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

1

0

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

6

0

E

c

u

a

d

o

r

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

2

8

0

3

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

7

5

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

4

6

K

a

z

a

k

h

s

t

a

n

$

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

2

7

9

9

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

2

4

8

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

7

5

V

i

e

t

N

a

m

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

3

3

8

7

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

1

3

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

7

2

A

z

e

r

b

a

i

j

a

n

$

$

$

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

3

4

4

0

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

4

9

3

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

1

8

6

A

r

g

e

n

t

i

n

a

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

4

5

1

1

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

5

5

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

7

4

A

n

g

o

l

a

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

6

0

9

5

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

7

5

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

1

4

8

I

r

a

q

$

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

7

8

9

6

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

2

8

4

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

7

0

O

m

a

n

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

9

2

4

6

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

1

1

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

6

7

A

l

g

e

r

i

a

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

1

0

4

0

2

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

7

6

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

3

1

C

h

i

n

a

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

1

8

8

4

6

0

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

7

0

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

1

4

0

R

u

s

s

i

a

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

8

7

8

3

6

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

0

8

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

3

9

S

a

u

d

i

A

r

a

b

i

a

$

$

3

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

2

0

1

3

:

$

6

6

9

9

6

m

.

l

n

o

r

e

a

s

e

s

i

n

o

e

2

0

0

4

:

1

1

8

0

L

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

0

4

-

1

3

:

6

8

F

i

g

u

r

e

4

.

T

h

e

c

o

u

n

t

r

i

e

s

t

h

a

t

d

o

u

b

l

e

d

m

i

l

i

t

a

r

y

s

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

b

e

t

w

e

e

n

2

0

0

4

a

n

d

2

0

1

3

N

o

t

e

s

:

$

$

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

s

t

h

a

t

t

h

e

c

o

u

n

t

r

y

s

m

i

l

i

t

a

r

y

s

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

d

o

u

b

l

e

d

(

o

r

m

o

r

e

)

,

$

$

$

t

h

a

t

i

t

t

r

i

p

l

e

d

(

o

r

m

o

r

e

)

,

$

$

$

$

t

h

a

t

i

t

q

u

a

d

r

u

p

l

e

d

(

o

r

m

o

r

e

)

a

n

d

$

$

$

$

$

t

h

a

t

i

t

q

u

i

n

t

u

p

l

e

d

(

o

r

m

o

r

e

)

,

a

l

l

i

n

r

e

a

l

t

e

r

m

s

.

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

s

t

h

a

t

t

h

e

c

o

u

n

t

r

y

i

s

a

s

i

g

n

i

c

a

n

t

o

i

l

p

r

o

d

u

c

e

r

i

n

r

e

l

a

t

i

o

n

t

o

t

h

e

s

i

z

e

o

f

i

t

s

e

c

o

n

o

m

y

.

I

n

m

o

s

t

c

a

s

e

s

,

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

s

t

h

a

t

t

h

e

c

o

u

n

t

r

y

e

x

p

e

r

i

e

n

c

e

d

(

s

t

a

t

e

-

b

a

s

e

d

)

w

a

r

o

r

m

i

n

o

r

a

r

m

e

d

c

o

n

i

c

t

o

r

n

o

n

-

s

t

a

t

e

c

o

n

i

c

t

d

u

r

i

n

g

t

h

e

p

e

r

i

o

d

2

0

0

4

1

3

,

a

s

d

e

n

e

d

b

y

t

h

e

U

C

D

P

C

o

n

i

c

t

E

n

c

y

c

l

o

p

e

d

i

a

,

<

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

w

w

w

.

u

c

d

p

.

u

u

.

s

e

/

>

.

T

h

e

e

x

c

e

p

t

i

o

n

i

s

A

r

m

e

n

i

a

,

w

h

e

r

e

i

t

r

e

f

e

r

s

t

o

t

h

e

f

r

o

z

e

n

c

o

n

i

c

t

w

i

t

h

A

z

e

r

b

a

i

j

a

n

o

v

e

r

N

g

o

r

n

o

-

K

a

r

a

b

a

k

h

.

trends in world military expenditure, 2013 7

Nearly all of the 23 countries display at least

one of three characteristics:

very strong economic growth,

high oil or gas revenues, or

signicant armed conict or other violence.

In all cases, growth of military spending

over the period was higher than growth in

GDP (both in real terms). Economic growth is

a clear driver in some cases, such as China and

Angola, but others countries have increased

military spending on the basis of much weaker

growth records.

A factor common to many of the countries is a

high level of revenue from oil and gas exports

in some cases, such as Ghana, recently discov-

ered or exploited. This resource provides a

ready source of income for the state that does

not require taxing the general population. However, the presence of such

natural resouces can generate new security concerns, either internal or

external. Poor governance of the revenues from natural resources may also

be a factor that tends to favour the diversion of those revenues to military

uses.

Many of the 23 countries have experienced armed conict over the period

or dangerous ongoing frozen conicts, such as that between Armenia and

Azerbaijan. The most striking example of a large rise in military expenditure

is Afghanistan (see box1). While there is no state-based armed conict in the

case of Honduras, the homicide rate there is among the highest in the world.

However, some of the countries, such as Ecuador, Kazakhstan, Namibia,

Paraguay and Swaziland, enjoy essentially peaceful security environments.

Box 1. Military spending in Afghanistan and the withdrawal of

ISAF

Not only did Afghanistan have the worlds highest increase in military

expenditure in 2013, at 77 per cent, spending had risen by 557 per

cent over the decade since 2004. This huge increase is the result of

Afghanistans eforts to build its defence and security forces from

scratch, heavily supported by foreign aid. The particularly large

increase in 2013 is the result of an increase in salaries and wages for

the Afghan National Army, which reached its target goal of 195 000

soldiers in 2012, and as a result of preparations for the departure of

most foreign forces at the end of 2014.

After more than a decade of operations in Afghanistan, the NATO-

led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission will end in

December 2014. By then, more than 350000 Afghan army and police

personnel will be responsible for the states security. Some other coun-

tries will continue to support the Afghan national security forces, but

they will not have a combat role.

SIPRI is an independent

international institute

dedicated to research into

conict, armaments, arms

control and disarmament.

Established in 1966, SIPRI

provides data, analysis and

recommendations, based on

open sources, to policymakers,

researchers, media and the

interested public.

GOVERNING BOARD

Gran Lennmarker, Chairman

(Sweden)

Dr Dewi Fortuna Anwar

(Indonesia)

Dr Vladimir Baranovsky

(Russia)

Ambassador Lakhdar Brahimi

(Algeria)

Jayantha Dhanapala

(SriLanka)

Ambassador Wolfgang

Ischinger (Germany)

Professor Mary Kaldor

(UnitedKingdom)

The Director

DIRECTOR

Professor Tilman Brck

(Germany)

SIPRI 2014

Signalistgatan 9

SE-169 70 Solna, Sweden

Telephone: +46 8 655 97 00

Fax: +46 8 655 97 33

Email: sipri@sipri.org

Internet: www.sipri.org

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr Sam Perlo-Freeman (United Kingdom) is Director of the SIPRI Military

Expenditure Programme.

Carina Solmirano (Argentina) is a Senior Researcher with the SIPRI Military

Expenditure Programme.

THE SIPRI MILITARY EXPENDITURE DATABASE

The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database provides military expenditure

data by country for the years 19882013

in local currency, at current prices,

in US dollars, at constant (2012) prices and exchange rates, and

as a share (%) of gross domestic product (GDP).

SIPRI military expenditure data is based on open sources only, including a

SIPRI questionnaire that is sent out annually to governments. The collected

data is processed to achieve consistent time series which are, as far as pos-

sible, in accordance with the SIPRI denition of military expenditure.

The database is available at <http://www.sipri.org/databases/milex/>.

The denition of military expenditure

Where possible, SIPRI military expenditure data includes all current and

capital expenditure on

the armed forces, including peacekeeping forces,

defence ministries and other government agencies engaged in defence

projects,

paramilitary forces, when judged to be trained and equipped for military

operations, and

military space activities.

Such expenditure should include

military and civil personnel, including retirement pensions of military

personnel and social services for personnel,

operations and maintenance,

procurement,

military research and development, and

military aid (in the military expenditure of the donor country).

Civil defence and current expenditure on previous military activitiessuch

as veterans benets, demobilization, conversion and weapon destruction

are excluded.

You might also like

- PESTLE Analysis of ChinaDocument4 pagesPESTLE Analysis of ChinaAmit Pathak67% (3)

- Deed of Conditional Sale Sample 13Document4 pagesDeed of Conditional Sale Sample 13Bng100% (1)

- Equity Valuation of MaricoDocument18 pagesEquity Valuation of MaricoPriyanka919100% (1)

- Early Morning ReidDocument2 pagesEarly Morning ReidCrodole0% (1)

- Decathlon Final Report 29th SeptDocument38 pagesDecathlon Final Report 29th Septannu100% (2)

- Traffic and Highway Engineering 5th Edition Garber Solutions ManualDocument27 pagesTraffic and Highway Engineering 5th Edition Garber Solutions Manualsorrancemaneuverpmvll100% (32)

- Tendances Des Dépenses MilitairesDocument8 pagesTendances Des Dépenses MilitairesAnonymous opV0GNQtwNo ratings yet

- Does Military Expenditure Increase External Debt? Evidence From AsiaDocument18 pagesDoes Military Expenditure Increase External Debt? Evidence From Asiamutaalimran2k3No ratings yet

- Is The Tide Rising?: Figure 1. World Trade Volumes, Industrial Production and Manufacturing PMIDocument3 pagesIs The Tide Rising?: Figure 1. World Trade Volumes, Industrial Production and Manufacturing PMIjdsolorNo ratings yet

- Comparison of UAE and French EconomyDocument16 pagesComparison of UAE and French EconomyuowdubaiNo ratings yet

- World Air Cargo Forecast 2014 2015Document68 pagesWorld Air Cargo Forecast 2014 2015Ankit Varshney100% (1)

- World Military ExpendituresDocument4 pagesWorld Military ExpenditureskofiadrakiNo ratings yet

- Trends in US Military Spending 2014 - FinalDocument10 pagesTrends in US Military Spending 2014 - Finalmutaalimran2k3No ratings yet

- World Defence Spendings at The Begining of The 3 MilleniumDocument8 pagesWorld Defence Spendings at The Begining of The 3 MilleniumPavel TraianNo ratings yet

- Parent Company Category Sector Tagline/ Slogan STP SegmentDocument5 pagesParent Company Category Sector Tagline/ Slogan STP SegmentMohammedNaushadNo ratings yet

- Government Finance: Taxation in The United States United States Federal BudgetDocument7 pagesGovernment Finance: Taxation in The United States United States Federal BudgetKatt RinaNo ratings yet

- Echartbook Q21 2013 PDFDocument7 pagesEchartbook Q21 2013 PDF15221122069No ratings yet

- Echapter Vol2Document214 pagesEchapter Vol2dev shahNo ratings yet

- State of The Economy: An OverviewDocument30 pagesState of The Economy: An OverviewsujoyludNo ratings yet

- Towards The Challenges of A Contemporary World: Editors: Robert Czulda Robert ŁośDocument9 pagesTowards The Challenges of A Contemporary World: Editors: Robert Czulda Robert ŁośDaniel MarinNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomic Developments and Securities MarketsDocument16 pagesMacroeconomic Developments and Securities MarketsJugal AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Political Sci - IJPSLIR - Indias Foreign Policy - Suresh DhandaDocument14 pagesPolitical Sci - IJPSLIR - Indias Foreign Policy - Suresh DhandaTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Market Research Report: HNWI Asset Allocation in The US 2014Document8 pagesMarket Research Report: HNWI Asset Allocation in The US 2014api-272965018No ratings yet

- Asia 2015Document5 pagesAsia 2015Prithvijeet SinghNo ratings yet

- 2013 Aded Annual Report enDocument76 pages2013 Aded Annual Report enapi-254134307No ratings yet

- 2015 Private Equity Market Outlook From TorreyCove Capital PartnersDocument51 pages2015 Private Equity Market Outlook From TorreyCove Capital PartnersTed BallantineNo ratings yet

- I. Output: Global Recovery Prospects Remain WeakDocument8 pagesI. Output: Global Recovery Prospects Remain Weakanjan_debnathNo ratings yet

- MENA PE Year 2014 (Annual Edition)Document21 pagesMENA PE Year 2014 (Annual Edition)IgnoramuzNo ratings yet

- Economicoutlook 201314 HighlightsDocument5 pagesEconomicoutlook 201314 Highlightsrohit_pathak_8No ratings yet

- Fiscal Shock Combat AweDocument11 pagesFiscal Shock Combat AwemleppeeNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 3 National Income and Related Aggregates 3.1 Background: Performance of An Economy Depends On The Amount ofDocument21 pagesChapter - 3 National Income and Related Aggregates 3.1 Background: Performance of An Economy Depends On The Amount ofnavneetNo ratings yet

- Sipri - Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2019Document12 pagesSipri - Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2019Nelson DüringNo ratings yet

- Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2019: SIPRI Fact SheetDocument12 pagesTrends in World Military Expenditure, 2019: SIPRI Fact SheetRadamésRodriguesNo ratings yet

- Global Economic Outlook Prospects For The World Economy in 2014-2015 Global Growth Continues To Face HeadwindsDocument11 pagesGlobal Economic Outlook Prospects For The World Economy in 2014-2015 Global Growth Continues To Face HeadwindsBen KuNo ratings yet

- Country Strategy 2011-2014 RussiaDocument18 pagesCountry Strategy 2011-2014 RussiaBeeHoofNo ratings yet

- BillpressreleaseDocument5 pagesBillpressreleaseapi-336846248No ratings yet

- PC 2013 03Document14 pagesPC 2013 03BruegelNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Economic Survey FY03Document267 pagesPakistan Economic Survey FY03Farooq ArbyNo ratings yet

- Cerb 2014Document6 pagesCerb 2014Jeannine WatsonNo ratings yet

- Economic Survey2013-14Document254 pagesEconomic Survey2013-14kunal1104No ratings yet

- What's Next For NATO?Document8 pagesWhat's Next For NATO?Center for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Economic Effect On MilitaryDocument29 pagesEconomic Effect On MilitaryFahrian YovantraNo ratings yet

- Global Defense Spending SnapshotDocument15 pagesGlobal Defense Spending SnapshotVictor PileggiNo ratings yet

- CBQrterRev Q12018 en 0Document47 pagesCBQrterRev Q12018 en 0aspany loisNo ratings yet

- 2016wesp Ch1 enDocument50 pages2016wesp Ch1 enMuhamad Amirul FikriNo ratings yet

- Maersk Logistics (Business Strategy and Policies)Document11 pagesMaersk Logistics (Business Strategy and Policies)HK FreeNo ratings yet

- FOIMemo 8023Document14 pagesFOIMemo 8023John DoahNo ratings yet

- Budget FY14Document89 pagesBudget FY14hossainmzNo ratings yet

- The Lack of Aid For SureDocument1 pageThe Lack of Aid For SureVinod PatilNo ratings yet

- A Brief Overview of The Middle East Arm TradeDocument5 pagesA Brief Overview of The Middle East Arm TradeQianfeng YinNo ratings yet

- Monarch Report 4/8/2013Document3 pagesMonarch Report 4/8/2013monarchadvisorygroupNo ratings yet

- Chart 3.1: Outlook For Real GDP Growth in 2012Document1 pageChart 3.1: Outlook For Real GDP Growth in 2012Sha Kah RenNo ratings yet

- State of EconomyDocument21 pagesState of EconomyHarsh KediaNo ratings yet

- Market Outlook Market Outlook: Dealer's DiaryDocument14 pagesMarket Outlook Market Outlook: Dealer's DiaryAngel BrokingNo ratings yet

- Senior Exit Final Draft Needs WorkDocument10 pagesSenior Exit Final Draft Needs Workapi-284250573No ratings yet

- Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2014-USDocument40 pagesEconomic and Fiscal Outlook 2014-USMaggie HartonoNo ratings yet

- Building BricksDocument28 pagesBuilding BricksalicecicaNo ratings yet

- I. The World Economy and Trade in 2013 and Early 2014Document22 pagesI. The World Economy and Trade in 2013 and Early 2014RameezNo ratings yet

- Weekly Economic Commentary 4/29/2013Document6 pagesWeekly Economic Commentary 4/29/2013monarchadvisorygroupNo ratings yet

- 2 - Ali and Abdellatif - Military Expenditures and Natural Resources (ME and N Africa)Document11 pages2 - Ali and Abdellatif - Military Expenditures and Natural Resources (ME and N Africa)swjiNo ratings yet

- EIB Investment Survey 2023 - European Union overviewFrom EverandEIB Investment Survey 2023 - European Union overviewNo ratings yet

- SIPRI Yearbook 2015 Summary in EnglishDocument32 pagesSIPRI Yearbook 2015 Summary in EnglishStockholm International Peace Research Institute100% (1)

- Western Arms Exports To ChinaDocument68 pagesWestern Arms Exports To ChinaStockholm International Peace Research Institute100% (1)

- Measuring Turkish Military ExpenditureDocument20 pagesMeasuring Turkish Military ExpenditureStockholm International Peace Research InstituteNo ratings yet

- South Korea's Export Control SystemDocument20 pagesSouth Korea's Export Control SystemStockholm International Peace Research InstituteNo ratings yet

- Strengthening The European Union's Future Approach To WMD Non-ProliferationDocument64 pagesStrengthening The European Union's Future Approach To WMD Non-ProliferationStockholm International Peace Research InstituteNo ratings yet

- SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operation Deployments, September 2012Document1 pageSIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operation Deployments, September 2012Stockholm International Peace Research InstituteNo ratings yet

- Measuring International Arms TransfersDocument8 pagesMeasuring International Arms TransfersStockholm International Peace Research InstituteNo ratings yet

- Manipulating The World Economy or Just Understanding How It Really Functions?Document7 pagesManipulating The World Economy or Just Understanding How It Really Functions?Tom BaccoNo ratings yet

- ACCOUNTINGDocument12 pagesACCOUNTINGharoonadnan196No ratings yet

- Too Big To FailDocument247 pagesToo Big To Failwwfpyf100% (3)

- BH-7 Inspector'S Test W/On-Off Unit With Brass Sight Class: ASTM B16 C36000Document1 pageBH-7 Inspector'S Test W/On-Off Unit With Brass Sight Class: ASTM B16 C36000saus sambalNo ratings yet

- Unit 1. Fundamentals of Managerial Economics (Chapter 1)Document50 pagesUnit 1. Fundamentals of Managerial Economics (Chapter 1)Felimar CalaNo ratings yet

- Womens Hostel in BombayDocument5 pagesWomens Hostel in BombayAngel PanjwaniNo ratings yet

- AntiglobalizationDocument26 pagesAntiglobalizationDuDuTranNo ratings yet

- Countries With Capitals and Currencies PDF Notes For All Competitive Exams and Screening TestsDocument12 pagesCountries With Capitals and Currencies PDF Notes For All Competitive Exams and Screening Testsabsar ahmedNo ratings yet

- A Brief Analysis On The Labor Pay of Government Employed Registered Nurses (RN) in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesA Brief Analysis On The Labor Pay of Government Employed Registered Nurses (RN) in The PhilippinesMary Joy Catherine RicasioNo ratings yet

- Rasanga Curriculum VitaeDocument5 pagesRasanga Curriculum VitaeKevo NdaiNo ratings yet

- Ten Principles of UN Global CompactDocument2 pagesTen Principles of UN Global CompactrisefoxNo ratings yet

- Important InformationDocument193 pagesImportant InformationDharmendra KumarNo ratings yet

- Fdi Inflows Into India and Their Impact On Select Economic Variables Using Multiple Regression ModelDocument15 pagesFdi Inflows Into India and Their Impact On Select Economic Variables Using Multiple Regression ModelAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Report On Brick - 1Document6 pagesReport On Brick - 1Meghashree100% (1)

- Political Economy of Media - A Short IntroductionDocument5 pagesPolitical Economy of Media - A Short Introductionmatthewhandy100% (1)

- TaylorismDocument41 pagesTaylorismSoujanyaNo ratings yet

- TUT. 1 Regional Integration (Essay)Document2 pagesTUT. 1 Regional Integration (Essay)darren downerNo ratings yet

- Team Energy Corporation, V. Cir G.R. No. 197770, March 14, 2018 Cir V. Covanta Energy Philippine Holdings, Inc., G.R. No. 203160, January 24, 2018Document5 pagesTeam Energy Corporation, V. Cir G.R. No. 197770, March 14, 2018 Cir V. Covanta Energy Philippine Holdings, Inc., G.R. No. 203160, January 24, 2018Raymarc Elizer AsuncionNo ratings yet

- No. 3 CambodiaDocument2 pagesNo. 3 CambodiaKhot SovietMrNo ratings yet

- CH 8 The Impacts of Tourism On A LocalityDocument19 pagesCH 8 The Impacts of Tourism On A LocalityBandu SamaranayakeNo ratings yet

- N 1415 Iso - CD - 3408-5 - (E) - 2003 - 08Document16 pagesN 1415 Iso - CD - 3408-5 - (E) - 2003 - 08brunoagandraNo ratings yet

- GCCA Newsletter - FEBRUARY 2023Document1 pageGCCA Newsletter - FEBRUARY 2023ArnaldoFortiBattaginNo ratings yet

- API CAN DS2 en Excel v2 10038976Document458 pagesAPI CAN DS2 en Excel v2 10038976sushant ahujaNo ratings yet

- Life Cycle AssessmentDocument11 pagesLife Cycle Assessmentrslapena100% (1)

- Rethinking Social Protection Paradigm-1Document22 pagesRethinking Social Protection Paradigm-1herryansharyNo ratings yet

- RECEIPTSDocument6 pagesRECEIPTSLyka DanniellaNo ratings yet