Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MR in Acute Rheumatic

Uploaded by

Genta PradanaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MR in Acute Rheumatic

Uploaded by

Genta PradanaCopyright:

Available Formats

Physicians)? 2007443134137Original ArticlesFulminant acute rheumatic feverY Anderson et al.

doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01214.x

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Fulminant mitral regurgitation due to ruptured chordae tendinae in acute rheumatic fever

Yvonne Anderson,1 Nigel Wilson,2 Ross Nicholson1 and Kirsten Finucane2

1

Kidz First Childrens Hospital, Middlemore Hospital, South Auckland and 2Paediatric Cardiac Services, Starship Childrens Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand

Aims: Description of the presentation and management of cases of fulminant mitral regurgitation in acute rheumatic fever (ARF). Methods: Retrospective case series of 4 children, aged 610 years, presenting in acute pulmonary oedema because of rupture of elongation of the chordae tendinae of the mitral valve leading to ail leaets and severe mitral regurgitation. Results: Urgent cardiac surgery with mitral valve repair was performed. Resolution of heart failure was achieved in each case. The difculties in diagnosis and management of this uncommon and often unrecognised presentation of ARF are discussed. Conclusions: Cardiac surgery can be life saving for fulminant mitral regurgitation due to rupture of chordae tendinae of the mitral valve in ARF Key words: acute rheumatic fever; mitral regurgitation; ruptured chordae tendinae.

Rupture of chordae tendinae secondary to acute rheumatic fever (ARF) as part of the acute presentation phase was rst reported in 1968,1 and in a series of four patients in 1986.2 Since then single cases only have been reported.35 We report four children with rheumatic fever presenting to one hospital in New Zealand over a ve month period with chordal rupture or elongation leading to severe mitral regurgitation (MR) and pulmonary oedema.

Patients

Each of the four patients initially presented to the Accident and Emergency Department of the Kidz First Childrens Hospital with the symptoms and signs of respiratory distress as outlined in Table 1. Patient two had a history of respiratory distress, but on arrival at the Emergency Department, had depressed level of consciousness and decreased respiratory effort. All had relatively normal left atrial (LA) and left ventricular (LV) size on electrocardiography (ECG). Rupture or lengthening of the chordae tendinae was recognised by echocardiography in

three of the four patients prior to surgery. Three of the four patents were managed with mechanical ventilation and the fourth was in respiratory failure despite high dose diuretics and oxygen prior to surgery (Table 2). The indication for surgical intervention was deterioration despite maximal medical treatment in the intensive care setting. The surgical and histological ndings, type of operation and outcome are outlined in Table 2. The mitral valve chordae tendinae were signicantly elongated or ruptured in all cases with subsequent ail segments of the mitral valve leaets which had resulted in torrential MR. In all four cases, mitral valve repair was undertaken but two patients have subsequently required mitral valve replacement for recurrent progressive MR.

Discussion

The classical signs of rheumatic ruptured chordae tendinae are pulmonary oedema in the presence of severe MR because of acute mitral valve prolapse. The left atrium is relatively noncompliant and this leads to a rapid rise in LA pressure, pulmonary venous pressure and overt pulmonary oedema. The jugular venous pressure may also be raised as the V wave is transmitted through the right atrium.6 Breathlessness is marked, and the acute pulmonary oedema is evident by blood stained sputum, seen in two of the cases. Initially, there is no or minimal LA enlargement on ECG, chest X-ray and echocardiography. In the presence of severe MR, this nding alone should alert one to the possibility that this is an acute problem, likely because of mechanical disruption of the mitral chordae tendinae. The left ventricle will dilate more quickly than the left atrium, but this is much more modest than in classical severe MR in ARF that evolved over weeks and months. Pulmonary oedema may be patchy or one-sided, and this has led some authors calling the condition, wrongfully in our view, rheumatic pneumonia.7 Clinicians and paediatricians assessing

Key Points 1 Pulmonary oedema in acute rheumatic fever is likely due to rupture of chordae tendinae of the mitral valve without left atrial dilatation. 2 Such cases are often misdiagnosed as acute pneumonia. 3 Urgent cardiac surgery may be life-saving.

Correspondence: Dr Nigel Wilson, Paediatric Cardiac Services, Starship Childrens Hospital, Private Bag 92 024, Auckland, New Zealand. Fax: +64 9631 0785; email: nigelw@adhb.govt.nz Accepted for publication 3 July 2007.

134

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 44 (2008) 134137 2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (Royal Australasian College of Physicians)

Y Anderson et al.

Fulminant acute rheumatic fever

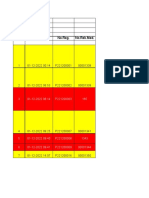

Table 1 Clinical presentation and investigation Case Age (years) 10 Ethnicity Presenting symptoms Cough, fever, dyspnoea 2 days, blood stained sputum 1 day Malaise 1 week, dyspnoea, decreased LOC 1 day (Down Syndrome) Dyspnoea, cough, vomiting, abdominal/sternal pain 3 days, blood stained sputum, decreased appetite 2 days Intermittent fever, decreased appetite, vomiting, lethargy, 3 weeks, sore left knee/ankle 7 weeks, sore chest, dyspnoea 3 days Initial working diagnosis Pneumonia Examination ndings Tachycardic, tachypnoiec, desaturation, hepatomegaly, PSM Hypothermic, hypoglycaemic, bradypnoiec, unrecordable saturations, GCS = 7/15, pulsatile hepatomegaly, PSM, EDM Temperature = 36.2, tachypnoiec, respiratory distress, desaturations, displaced apex, apical PSM, hepatomegaly JVP = 4 cm, 4/6 apical PSM, 3/6 aortic diastolic murmur, hepatomegaly, bibasal crepitations ASOT/ anti-Dnase (IU) 223/1670 (13 days post presentation) 631/2360 (4 days post presentation) 154/396 (3 days post presentation) 803/1090 (day of presentation) ESR (mm)

NZ Maori Pacic Island

10

Cook Island Maori NZ Maori

Septic shock, ?paracetamol overdose Infective endocarditis Acute hypoxia/ tachypnoea, ?pneumonia/cardiac failure ARF

37

74

97

Electrocardiography Sinus tachycardia, normal LA & LV size Normal LA & LV size

Chest X-ray (as interpreted by clinician) Density right lung, left lower lobe interstitial oedema. Bilateral bronchopneumonia (Fig. 1) Mild cardiomegaly, bilateral pleural effusion, bilateral lower lobe consolidation Marked consolidation right lung and perihilar region left lung due to bilateral pulmonary oedema (Fig. 2) Globular heart, moderately enlarged. No signicant pulmonary oedema or pleural uid.

Echocardiogram ARF with ruptured chordae and ail posterior mitral valve leaet. Severe/torrential MR. Mild TR with RVSP 30 mmHg + right atrial pressure. Mild LA and LV dilatation and normal LV function. Severe AR with possible aortic root abscess. Severe MR with possible anterior leaet perforation. Mild TR. Mild PR. Small lateral pericardial effusion. Moderate PHT. Torrential MR from a ail PMVL. Mild LA dilatation. Hyperdynamic LV systolic function. Signicant PHT. AMVL prolapse due to ruptured and elongated chord. Severe MR. Moderate LA dilatation. Dilated LV with good LV systolic function. Mild AR. Mild TR. PHT.

Sinus tachycardia, LA size increased Normal LA size Mild LVH by voltage

AMVL, anterior mitral valve leaet; AR, aortic regurgitation; ARF, acute rheumatic fever; EDM, early diastolic murmur; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; JVP, jugular venous pressure; LOC, level of consciousness; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; LVH, Left ventricular hypertrophy; MCL, mid-clavicular line; MR, mitral regurgitation; PH/R, heart pulse rate; PHT, pulmonary hypertension; PMVL, posterior mitral valve leaet; PSM, pan systolic murmur; PR, pulmonary regurgitation; R/R, respiratory rate. RV, right ventricle; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

children may be reluctant to make the diagnosis of pulmonary oedema in children but understanding the pathophysiology of this entity can enable the correct diagnosis in regions where there is rheumatic fever. This series of children is older than that presented by de Moor,2 and surgical intervention was performed earlier. This is partly because of experience of valve repair at our institution. The cardiac diagnoses were all made by echocardiography and no patient underwent cardiac catheterisation. However, in each case, there were still diagnostic challenges, with misinterpretation of clinical and radiographic pulmonary oedema as pneumonia by the emergency clinicians. Since De Moors report in 1986,2 there have been advances in mitral valve repair and the majority of patients with rheumatic mitral prolapse are amenable to valve repair.810 Surgical techniques include shortening of stretched tendinae or insertion of gortex chords to correct prolapse. The degree of annular dilatation is less in acute cases but annuloplasty may still be used. There will be ongoing inam-

mation after surgery in these fulminant cases of ARF and a limited annuloplasty helps to prevent dilatation of the posterior annulus and preserve the oval shape of the mitral annulus. Conservation of the mitral valve is now possible in most children requiring surgery for ARF but the difculty of surgical intervention because of the friability of the inamed tissue makes this a challenge. Because of the ongoing inammation of rheumatic carditis which can last for 36 months,11 it is not surprising that with time, revisional surgery or even mitral valve replacement may be necessary. Symptoms associated with severe MR with ARF which evolved over a number of weeks or months usually respond to patient rest and diuretics. Indeed, it is our practice not to operate acutely if symptoms are under control. If valve surgery is indicated because of LV chamber size or LV function, this can usually be deferred until the inammatory markers, C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), have subsided. Case 4, with a seven week history, represents a

135

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 44 (2008) 134137 2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (Royal Australasian College of Physicians)

Fulminant acute rheumatic fever

Y Anderson et al.

Table 2 Surgical management, and outcome Initial management Ventilation, inotropes Ventilation, inotropes Ventilated, inotropes Diuretics, oxygen. Monitored in intensive care unit Surgical ndings 3 of 4 major chordae to PMVL ruptured Pericarditis, inamed AMVL, AMVL stretched chordae No vegetations Major chordae group to PMVL ruptured with half ail leaet Ruptured central chord AMVL, stretched other AMVL chords, medial PMVL prolapse with elongated chords Day of surgery from admission Surgical management Day 1. Mitral valve repair including insertion of articial chordae and 26 mm Carpentier Edward ring. Day 5. Homograft aortic root replacement. Mitral valve repair using 24 mm Carpentier ring. Tricuspid annuloplasty. Day 3. Mitral valve repair. Annuloplasty ring not used. Day 3. Mitral valve repair using 24 mm Carpentier Edwards ring and tricuspid annuloplasty. Histology Uninterpretable as tissue not xed over weekend. Acute and chronic inammation. Acute inammation with some Aschoff bodies. Leaet had nodular thickening, early brosis.

Outcome of mitral repair in hospital Resolution of symptoms. Trivial MR. Mobilised early. Resolution of symptoms, mild MR. Resolution of symptoms, mild MR. Resolution of symptoms, moderate MR, mobilised cautiously.

Latest follow-up MR returned over 2 months. MV replacement 11 months post MV repair. NYHA 1 on warfarin. Moderate MR at 8 months post MV repair. Asymptomatic. 22 months post MV repair. NYHA 1. Mitral valve replacement 10 months after repair for severe MR. NYHA 1 on warfarin.

AMVL, anterior mitral valve leaet; AR, aortic regurgitation; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MR, mitral regurgitation; MV, mitral valve; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PHT, pulmonary hypertension; PMVL, posterior mitral valve leaet; PR, pulmonary regurgitation; RV, right ventricle; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

Fig. 1 Chest X-ray of case 1 on presentation showing bilateral pulmonary oedema.

Fig. 2 Chest X-ray of case 3 on presentation showing dense pulmonary oedema with dominant right lung involvement.

scenario in between the fulminant life threatening pulmonary oedema of cases 13 and the more typical ARF with severe MR progressing over weeks. As this patient was in cardiorespiratory failure, operation could not be deferred. The operation of choice for chronic rheumatic MR is valve repair.8 Lower operative mortality and better late outcome support efforts to repair the valves acutely when patients are failing medical treatment.9,10

136

The role of corticosteroids or bed rest for continued rheumatic inammation following valve surgery has not been studied nor likely to be, due to small numbers of patients and multiple confounding factors. It is difcult to estimate the incidence of chordal rupture or gross elongation resulting in severe sudden onset heart failure in ARF. We estimate this occurs in 13% of true rst episodes

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 44 (2008) 134137 2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (Royal Australasian College of Physicians)

Y Anderson et al.

Fulminant acute rheumatic fever

of ARF. This is based on the number of cases seen per year. Currently, between 100 and 150 new cases of ARF occur in New Zealand per year. Other evidence comes from the recently reported series from Utah12 as well postmortem series of children dying of ARF. It is likely that there are still many children in developing countries who die acutely with this complication because it is not recognised or accurate echocardiography is not available, or there is limited access to cardiac surgical units.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Barbara Semb, Research Secretary, Green Lane Research and Education Fund for secretarial assistance.

References

1 Hwang W, Lam K. Rupture of chordae tendinae during acute rheumatic carditis. Br. Heart J. 1968; 30: 42931. 2 De Moor M, Lachman P, Human D. Rupture of tendinous chords during acute rheumatic carditis in young children. Int. J. Cardiol. 1986; 12: 3537.

3 Wu YN, Lue HC, Hou SH, How SW. Rupture of chordae tendinae in acute rheumatic carditis: report of one case. Chung-Hua Min Kuo Hsiao Erh Koi Hseuh Hui Tsa Chih 1992; 33: 37682. 4 Haizlip J, Di Russo G, Vernon D, Tani L. Flail posterior leaet of the mitral valve in acute rheumatic carditis. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2004; 25: 1656. 5 El-Menyar A, Al-Hroob A, Numan M, Gendi S, Fawzy I. Unilateral pulmonary edema: unusual presentation of acute rheumatic fever. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2005; 26: 7002. 6 Braunwald E. Valvular heart disease. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart Disease, Vol. 2, 4th edn. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 1992; 10267. 7 Mahajan C, Bidwai P, Walia B, Berry J. Some uncommon manifestations of rheumatic fever. Indian J. Pediatr. 1973; 40: 1025. 8 Talwar S, Rajesh MR, Subramanian A, Saxena A, Kumar AS. Mitral valve repair in children with rheumatic heart disease. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005; 129: 8759. 9 Chauvaud S, Fuzellier JF, Berrebi A, Deloche A, Fabiani JN, Carpentier A. Long-term (29 years) results of reconstructive surgery in rheumatic mitral valve insufciency. Circulation 2001; 104 (12 Suppl. 1): I1215. 10 Enriquez-Sarano M, Schaff HV, Orszulak TA, Tajik AJ, Bailey KR, Frye RL. Valve repair improves the outcome of surgery for mitral regurgitation. A multivariate analysis. Circulation 1995; 91: 10228. 11 Park Myung K. The Pediatric Cardiology Handbook, 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby, An afliate of Elsevier Science, 2003; 1495. 12 Hillman ND, Tani LY, Veasy LG et al. Current status of surgery for rheumatic carditis in children. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004; 78: 14038.

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 44 (2008) 134137 2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (Royal Australasian College of Physicians)

137

You might also like

- Moleculer Mechanism GBSDocument13 pagesMoleculer Mechanism GBSGenta PradanaNo ratings yet

- Rheumatic Heart ChoreaDocument5 pagesRheumatic Heart ChoreaGenta PradanaNo ratings yet

- Vis AnthraxDocument2 pagesVis AnthraxGenta PradanaNo ratings yet

- FUNDUSCOPY HoDocument29 pagesFUNDUSCOPY HoGenta PradanaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chapter-14 - Person and CareersDocument69 pagesChapter-14 - Person and CareersMarlon SagunNo ratings yet

- 20190904020842HI Kobelco Tier 4 Final SK140SRL BrochureDocument2 pages20190904020842HI Kobelco Tier 4 Final SK140SRL BrochureAkhmad SebehNo ratings yet

- Fire & Gas Design BasisDocument2 pagesFire & Gas Design BasisAdil MominNo ratings yet

- CAPE Biology 2006 U2 P1 PDFDocument28 pagesCAPE Biology 2006 U2 P1 PDFvedant seerattanNo ratings yet

- CPRMSE GuidelinesDocument2 pagesCPRMSE GuidelinesDeepak KumarNo ratings yet

- Electro BladeDocument2 pagesElectro Bladeapi-19808945No ratings yet

- Final Draft - Banana ChipsDocument34 pagesFinal Draft - Banana ChipsAubrey Delgado74% (35)

- Effects of Climate ChangeDocument10 pagesEffects of Climate ChangeJan100% (1)

- TADO Smart Thermostat ManualDocument16 pagesTADO Smart Thermostat ManualMark WillisNo ratings yet

- Guidance On The 2010 ADA Standards For Accessible Design Volume 2Document93 pagesGuidance On The 2010 ADA Standards For Accessible Design Volume 2Eproy 3DNo ratings yet

- The Benefit of Power Posing Before A High-Stakes Social EvaluationDocument20 pagesThe Benefit of Power Posing Before A High-Stakes Social EvaluationpaolaNo ratings yet

- O-Rings & SealsDocument10 pagesO-Rings & SealsPartsGopher.comNo ratings yet

- Habit TrackersDocument38 pagesHabit Trackersjesus100% (1)

- Paper TropicsDocument8 pagesPaper Tropicsdarobin21No ratings yet

- Marital Rape in IndiaDocument8 pagesMarital Rape in IndiaSHUBHANK SUMANNo ratings yet

- t-47 Residential Real Property Affidavit - 50108 ts95421Document1 paget-47 Residential Real Property Affidavit - 50108 ts95421api-209878362No ratings yet

- Full Test 14 (Key) PDFDocument4 pagesFull Test 14 (Key) PDFhoang lichNo ratings yet

- 01 Basic Design Structure FeaturesDocument8 pages01 Basic Design Structure FeaturesAndri AjaNo ratings yet

- 6d Class 10Document10 pages6d Class 10Euna DawkinsNo ratings yet

- تحليل البول بالصور والشرحDocument72 pagesتحليل البول بالصور والشرحDaouai TaaouanouNo ratings yet

- Crypto Hash Algorithm-Based Blockchain Technology For Managing Decentralized Ledger Database in Oil and Gas IndustryDocument26 pagesCrypto Hash Algorithm-Based Blockchain Technology For Managing Decentralized Ledger Database in Oil and Gas IndustrySIMON HINCAPIE ORTIZNo ratings yet

- ICH Topic Q 3 B (R2) Impurities in New Drug Products: European Medicines AgencyDocument14 pagesICH Topic Q 3 B (R2) Impurities in New Drug Products: European Medicines AgencyJesus Barcenas HernandezNo ratings yet

- CKD EsrdDocument83 pagesCKD EsrdRita Lakhani100% (1)

- Ventilation SystemDocument13 pagesVentilation SystemSaru BashaNo ratings yet

- RICKETSDocument23 pagesRICKETSDewi SofyanaNo ratings yet

- Original Instruction Manual: Hypro Series 9303Document24 pagesOriginal Instruction Manual: Hypro Series 9303vandoNo ratings yet

- Ate-U2 - Steam Boilers - PPT - Session 3Document13 pagesAte-U2 - Steam Boilers - PPT - Session 3MANJU R BNo ratings yet

- Typhoid FeverDocument9 pagesTyphoid FeverAli Al.JuffairiNo ratings yet

- Lappasieugd - 01 12 2022 - 31 12 2022Document224 pagesLappasieugd - 01 12 2022 - 31 12 2022Sri AriatiNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument26 pagesThesiscmomcqueenNo ratings yet