Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Untitled

Uploaded by

api-2274330890 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

113 views8 pagesCalifornia's volatile fiscal performance has led to the need for a stronger reserve. A revision of a reserve proposal would fund the reserve through excess capital gains tax revenue. Standard and poor's rating services: states that are capable of consistently doing this are better positioned when the next revenue downturn strikes. But following a reserve policy does not ensure that it will actually come to fruition.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCalifornia's volatile fiscal performance has led to the need for a stronger reserve. A revision of a reserve proposal would fund the reserve through excess capital gains tax revenue. Standard and poor's rating services: states that are capable of consistently doing this are better positioned when the next revenue downturn strikes. But following a reserve policy does not ensure that it will actually come to fruition.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

113 views8 pagesUntitled

Uploaded by

api-227433089California's volatile fiscal performance has led to the need for a stronger reserve. A revision of a reserve proposal would fund the reserve through excess capital gains tax revenue. Standard and poor's rating services: states that are capable of consistently doing this are better positioned when the next revenue downturn strikes. But following a reserve policy does not ensure that it will actually come to fruition.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

The Challenge Of Establishing A State

Budget Reserve: The California

Example

Primary Credit Analyst:

Gabriel J Petek, CFA, San Francisco (1) 415-371-5042; gabriel.petek@standardandpoors.com

Secondary Contact:

David G Hitchcock, New York (1) 212-438-2022; david.hitchcock@standardandpoors.com

Table Of Contents

Key Provisions Of ACAX2-1

Will The Funding Mechanisms Work?

Assessing The Reserve Proposal

Recent Experience Demonstrates The Need For A Stronger Reserve

Mobilizing Support

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT MAY 6, 2014 1

1311487 | 301674531

The Challenge Of Establishing A State Budget

Reserve: The California Example

For state governments that are subject to balanced-budget requirements, harnessing periods of relatively stronger

revenue growth to build up a reserve makes intuitive sense. In Standard & Poor's Ratings Services' view, states that are

capable of consistently doing this are better positioned when the next revenue downturn strikes. Indeed, under our

state sector criteria, we assign a stronger budget management score to states that have a reserve policy that they can

likely follow. Nevertheless, this and the other benefits of following a reserve policy do not ensure that it will actually

come to fruition.

In California, a tendency to make long-term spending commitments in flush times without setting much aside for a

rainy day, combined with a heavy reliance on capital gains taxes, has led to volatile fiscal performance. Lawmakers are

considering replacing the currently proposed reserve policy before it goes to voters, scheduled for November. As the

concept for a new policy has evolved from the abstract to the more tangible, several technical issues related to its

potential implementation have emerged. It's possible that, in response, policymakers will decide to make some

adjustments to the governor's reserve proposal, ACAX2-1. But if these technical obstacles stymie lawmakers, and the

state fails to advance the cause of strengthening its reserve, it could prove to be a missed opportunity.

Overview

Much of California's revenue volatility arises from its reliance on capital gains taxes.

A revision of a reserve proposal would fund the reserve through excess capital gains tax revenue.

We believe, depending on the details, that such a measure could help improve the state's credit quality.

California legislators recently convened in a special session called by Gov. Jerry Brown to consider his budget reserve

proposal. The governor's recommendation, Assembly Constitutional AmendmentX2 1 (ACAX2-1), would replace an

existing "rainy day" fund proposal, ACA 4, currently scheduled to go before voters in the November 2014 election.

Before making it to the ballot, however, ACAX2-1 requires the approval of two-thirds of each house of the state

legislature. If the legislature sends it forward and a majority of voters support it, ACAX2-1 would replace Proposition

58, the state's current rainy day fund policy.

In our view, California's credit quality could benefit from a more robust budgetary reserve. Not only do we view the

consistency of deposits under its existing reserve policy (Proposition 58) as weaker than those of numerous other

states, but we have also cited California's revenue volatility as a limiting rating factor. These two attributes of

California's finances -- a weak or absent reserve fund mechanism combined with a volatile revenue base -- have

undermined the state's credit quality over the years. Therefore, we believe a policy requiring more regular deposits,

especially if it involves setting aside a portion of the state's tax collections when they spike, could help on both fronts.

That is what proponents of ACAX2-1, including the governor, assert the amendment would do. In fact, curbing the

effects of California's revenue volatility on its finances is central to the design of the policy proposal, according to the

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT MAY 6, 2014 2

1311487 | 301674531

Department of Finance (DOF).

As drafted, the amendment would attempt to tame revenue volatility by linking the requirement for a reserve deposit

to the performance of capital gains-related tax receipts. But importantly, in our view, the threshold level would be set

low enough to require a deposit in most years, according to the DOF. Specifically, the amendment calls for deposits

into the reserve whenever capital gains tax receipts equal or exceed 6.5% of general fund tax revenues. Despite the

financial market and budgetary turmoil of the past 10 years, capital gains tax receipts have cleared this hurdle seven

times.

Key Provisions Of ACAX2-1

Links requirement for reserve deposits to capital gains-related tax revenue performance

Increases maximum balance to 10% from current 5% of general fund revenue

Allows for certain debt repayment in-lieu of making deposits

Withdrawals and suspensions of deposits require governor's fiscal emergency declaration and majority agreement

from legislature

Restricts withdrawals to 50% of reserve balance in first year

Enshrines in constitution requirement for multiple-year general fund budget forecast

Establishes provisions for a separate Proposition 98 (school) reserve

Reserve Comparison

Proposition 58 ACA 4 ACAX2-1

Status In effect Currently scheduled for November

2014 election

Would replace ACA 4 on

November 2014 ballot if approved

by two-thirds of legislature

How is it funded? Three percent of general fund

revenue (half used for repayment

of economic recovery bonds until

they are retired)

1.5% of general fund revenue plus

revenue in excess of 20-year trend

or prior-year revenue once

adjusted for population and

inflation

Amount of capital gains revenue

above 6.5% of general fund tax

revenue. Split into Proposition 98

portion versus the remaining

amount for the budget stabilization

account (non-Proposition 98).

Funding level target (% of general

fund revenue)

Greater of $8 billion or 5% 10% of GF revenues 10% of general fund tax revenue in

budget stabilization reserve; 10%

of Proposition 98 allocation held in

separate Proposition 98 reserve.

May deposits be suspended? Yes, at governor's discretion By executive order only in years

when withdrawals would also be

permitted

Yes, if governor declares fiscal

emergency and majority of

legislature consents

Conditions for use of reserve None If revenue falls short of prior-year

spending once adjusted for

inflation and population

Governor must declare fiscal

emergency; majority of legislature

approval

Limits on withdrawals? None Maximum transfer out of 50% of

balance if there is a current year

budget shortfall.

Fifty percent of balance in first

year of budgetary emergency

GF--General fund.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT MAY 6, 2014 3

1311487 | 301674531

The Challenge Of Establishing A State Budget Reserve: The California Example

Will The Funding Mechanisms Work?

California's Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) has articulated some practical challenges with the governor's

reserve-fund proposal. Primary among them is the difficulty inherent to estimating personal income taxes (PIT) on net

capital gains. The policy, by linking deposits to performance of capital gains-related taxes, could therefore suffer from

the same uncertainty that it aims to address. Furthermore, final actual tax receipts attributed to net capital gains

remain in flux for up to two years. To address this, the proposal includes a true-up mechanism, so that initial deposits

may be increased or decreased through the two subsequent years. But such a process gives rise to the possibility that

transfers in or out of the reserve may be necessary at later points that are out of step with the then-prevailing

economic conditions.

For instance, if capital-gains revenue came in above the state's initial projection, the state could need to make a

deposit in a subsequent year. At that point, it's possible that economic conditions may have deteriorated.

Proponents of the measure argue that the provision establishing a Proposition 98 reserve would help smooth out the

amount of state funding that goes to education. In some years when the Proposition 98 formula calls for a large

increase in state funding to schools, instead of being disbursed, a portion of the funding would be retained in a separate

reserve. Funds held in the Proposition 98 reserve would be unavailable for non-Proposition 98 purposes. Instead, they

would be held until a year in which weaker general fund revenue performance allows the state to reduce funding for

education. Withdrawals would also be allowable even if the formula increased school funding but not by enough to

accommodate enrollment growth or cost-of-living increases.

In our view, a mechanism to level-out fluctuations in spending required by Proposition 98 could benefit the state's

budgetary performance. However, the specific conditions necessary to trigger a deposit, particularly general fund

revenue growth rates as measured in Proposition 98's formulas, have occurred only infrequently in past years. As we

understand it, however, rather than looking to past performance, the Proposition 98 reserve proposal reflects the

DOF's expectation of how general fund revenue will perform in the future. In our view, the key question is whether a

more progressive and PIT-reliant tax structure would result in frequent enough deposits to generate a meaningful

balance. If so, this reserve feature could help the state with managing spending-side volatility. But there is no way to

know the answer to this prior to the proposal's implementation.

On a related note, the LAO has pointed out that capital gains are not the state's only source of revenue volatility. By

our calculations, from one year to the next, state general fund tax revenues have increased as much as 20.3% and

declined as much as 17.2% during the past 15 years. But when we exclude capital gains-related PIT from the state's

general fund tax revenue, the range -- from 16.6% on the upside to negative 12.9% on the downside -- is somewhat

narrower. And two-thirds of the time during these 15 years, the swings in tax revenues have been more pronounced

when capital gains are included than when we exclude them.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT MAY 6, 2014 4

1311487 | 301674531

The Challenge Of Establishing A State Budget Reserve: The California Example

Assessing The Reserve Proposal

Deposits are linked to capital gains

In our view, no perfect way to neutralize revenue volatility exists. California's tax regime, as well as its demographic

and income distribution characteristics, probably makes a certain amount of revenue volatility unavoidable. By setting

the threshold low enough to require deposits in most years, as the proposal appears to do, it could significantly

strengthen the state's institutional commitment to a budget reserve. It could also, in our view, help to partly mitigate

the effects of the state's underlying revenue volatility on its finances.

Flexibility to repay debt is mostly favorable

In years when capital gains-related tax receipts would otherwise trigger a deposit to the reserve, the proposal allows

the governor and legislature to instead repay certain types of debt. In our view, some of the alternative uses of funds

that would be allowed under the amendment are more consistent with the concept of a budget reserve than others. In

particular, we view the ability of the governor and legislature to retire budgetary debts, such as internal loans or

payment deferrals, as most aligned with a rainy day fund. The state incurred these debts to fund its operating budget;

reversing them likewise restores fiscal capacity.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT MAY 6, 2014 5

1311487 | 301674531

The Challenge Of Establishing A State Budget Reserve: The California Example

The policy would also allow the state to make supplemental payments against unfunded pension or retiree health care

benefit liabilities in lieu of making a deposit. Similarly, it would permit using revenues to finance infrastructure

investment instead of making a deposit if doing so would supplant the issuance of previously authorized bonds. We

view paying down unfunded retiree benefit liabilities and avoiding additional debt as having merit from a credit

perspective. However, neither serves the same purpose as a budgetary reserve, which is to stabilize a state's finances

through a one- to three-year revenue slump.

That said, insofar as required contributions to the California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS) continue to

remain below the actuarially recommended level, any supplemental contributions are better than none. But allowing

these types of payments shouldn't be mistaken for a real solution to the state's underfunding problem related to

CalSTRS.

Recent Experience Demonstrates The Need For A Stronger Reserve

As the LAO has pointed out, the state has a track record of committing to new ongoing spending commitments during

years of stronger revenue growth. For example, we calculate that general fund tax revenues, in a reflection of the

technology boom, surged 69% between fiscal 1996 and 2001. General fund expenditures more than kept pace,

however, growing by 72% during the same period. But whereas tax revenues fell 17% in fiscal 2002, expenditures

ratcheted down by just 1.7%. In other words, the state had built the temporary higher revenues into its ongoing

spending base.

Had a reserve policy been in place that required saving a portion of the extraordinary revenue growth, it may have

lessened the state's mid-decade budget problems in two ways. First, the funds put in reserve would not have been

available to fund new spending commitments. Second, the state would have had more of a fiscal cushion to absorb the

fiscal 2002 tax revenue downturn. Instead, several fiscal policy decisions actually worsened the state's budget

situation.

In fiscal 2004, the state transitioned to a revenue structure that relied on cyclical PIT revenues by sharply reducing the

more stable motor vehicle license fee (MVLF). After the state confronted a $38.2 billion projected deficit heading into

fiscal 2004, the MVLF rate reduction in November 2003 exacerbated the fiscal strain. Whereas in May 2003 the state

estimated its structural gap for fiscal 2005 would be $7.9 billion, by January 2004 it had revised the structural deficit to

$14 billion. Ultimately, the state would finance much of its deficit problem with voter-approved debt without

successfully solving its underlying structural problems. Thus, rather than being flush from strengthening revenue in the

mid-decade years leading up to the Great Recession, the state was still contending with the fiscal hangover left from

the prior downturn. Then the Great Recession struck, and the state's structural gap ballooned to more than $20 billion.

By early 2011, the state faced a nearly $27 billion projected shortfall between revenues and spending. And, in addition

to having no budgetary reserve, it was carrying nearly $35 billion in budgetary debts. These obligations included

school aid deferrals, internal loans, and the bonds that had been issued beginning in 2004 solely to finance the state's

budget deficit. They were also distinct from its other long-term bonded debt obligations and liabilities for retiree

benefits.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT MAY 6, 2014 6

1311487 | 301674531

The Challenge Of Establishing A State Budget Reserve: The California Example

A reserve with the teeth to require deposits in better revenue years could have facilitated the creation of a fiscal

cushion while also having a disciplining effect on spending. Both would likely have benefited the state's credit quality

throughout the late 1990s and into the 2000s.

Mobilizing Support

When it comes to reaching a legislative supermajority on fiscal matters, California has a weak track record. Given this,

we cannot rule out the possibility that ACAX2-1 won't move forward. With its current composition, passage of the

amendment would require at least some bipartisan accord. On one side, the Republican minority caucus has suggested

that it may prefer more onerous restrictions on the state's ability to make withdrawals from the reserve. Conversely,

from the governor's own party, and in a demonstration of what we have termed "austerity fatigue," some policy

advocates have expressed reservations about putting funds in a reserve rather than deploying them for programs.

Sorting through these tensions, as well as refining the measure in light of the technical issues the LAO has raised,

represents a test of sorts for the state. But if the legislature succeeds in assembling the consensus necessary to move

the measure forward, it could mark another step in California's ongoing journey toward a more sustainable fiscal

structure.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT MAY 6, 2014 7

1311487 | 301674531

The Challenge Of Establishing A State Budget Reserve: The California Example

S&P may receive compensation for its ratings and certain analyses, normally from issuers or underwriters of securities or from obligors. S&P

reserves the right to disseminate its opinions and analyses. S&P's public ratings and analyses are made available on its Web sites,

www.standardandpoors.com (free of charge), and www.ratingsdirect.com and www.globalcreditportal.com (subscription) and www.spcapitaliq.com

(subscription) and may be distributed through other means, including via S&P publications and third-party redistributors. Additional information

about our ratings fees is available at www.standardandpoors.com/usratingsfees.

S&P keeps certain activities of its business units separate from each other in order to preserve the independence and objectivity of their respective

activities. As a result, certain business units of S&P may have information that is not available to other S&P business units. S&P has established

policies and procedures to maintain the confidentiality of certain nonpublic information received in connection with each analytical process.

To the extent that regulatory authorities allow a rating agency to acknowledge in one jurisdiction a rating issued in another jurisdiction for certain

regulatory purposes, S&P reserves the right to assign, withdraw, or suspend such acknowledgement at any time and in its sole discretion. S&P

Parties disclaim any duty whatsoever arising out of the assignment, withdrawal, or suspension of an acknowledgment as well as any liability for any

damage alleged to have been suffered on account thereof.

Credit-related and other analyses, including ratings, and statements in the Content are statements of opinion as of the date they are expressed and

not statements of fact. S&P's opinions, analyses, and rating acknowledgment decisions (described below) are not recommendations to purchase,

hold, or sell any securities or to make any investment decisions, and do not address the suitability of any security. S&P assumes no obligation to

update the Content following publication in any form or format. The Content should not be relied on and is not a substitute for the skill, judgment

and experience of the user, its management, employees, advisors and/or clients when making investment and other business decisions. S&P does

not act as a fiduciary or an investment advisor except where registered as such. While S&P has obtained information from sources it believes to be

reliable, S&P does not perform an audit and undertakes no duty of due diligence or independent verification of any information it receives.

No content (including ratings, credit-related analyses and data, valuations, model, software or other application or output therefrom) or any part

thereof (Content) may be modified, reverse engineered, reproduced or distributed in any form by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval

system, without the prior written permission of Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC or its affiliates (collectively, S&P). The Content shall not be

used for any unlawful or unauthorized purposes. S&P and any third-party providers, as well as their directors, officers, shareholders, employees or

agents (collectively S&P Parties) do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, timeliness or availability of the Content. S&P Parties are not

responsible for any errors or omissions (negligent or otherwise), regardless of the cause, for the results obtained from the use of the Content, or for

the security or maintenance of any data input by the user. The Content is provided on an "as is" basis. S&P PARTIES DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL

EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, ANY WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR

A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR USE, FREEDOM FROM BUGS, SOFTWARE ERRORS OR DEFECTS, THAT THE CONTENT'S FUNCTIONING

WILL BE UNINTERRUPTED, OR THAT THE CONTENT WILL OPERATE WITH ANY SOFTWARE OR HARDWARE CONFIGURATION. In no

event shall S&P Parties be liable to any party for any direct, indirect, incidental, exemplary, compensatory, punitive, special or consequential

damages, costs, expenses, legal fees, or losses (including, without limitation, lost income or lost profits and opportunity costs or losses caused by

negligence) in connection with any use of the Content even if advised of the possibility of such damages.

Copyright 2014 Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC, a part of McGraw Hill Financial. All rights reserved.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT MAY 6, 2014 8

1311487 | 301674531

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- CSEC POB June 2016 P1 With AnswersDocument8 pagesCSEC POB June 2016 P1 With AnswersJAVY BUSINESSNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Freeman Status PapersDocument18 pagesFreeman Status PapersDavid BrysonNo ratings yet

- Ex Parte - Tro.01Document14 pagesEx Parte - Tro.01Pinup Mosley100% (1)

- Solutions To Derivative Markets 3ed by McDonaldDocument28 pagesSolutions To Derivative Markets 3ed by McDonaldRiskiBiz13% (8)

- Ltcma Full ReportDocument130 pagesLtcma Full ReportclaytonNo ratings yet

- Sabah Offshore FieldsDocument16 pagesSabah Offshore FieldsMarlon Moncada50% (2)

- Sample Complaint For EjectmentDocument3 pagesSample Complaint For EjectmentPatrick LubatonNo ratings yet

- Michigan Outlook Revised To Stable From Positive On Softening Revenues Series 2014A&B Bonds Rated 'AA-'Document3 pagesMichigan Outlook Revised To Stable From Positive On Softening Revenues Series 2014A&B Bonds Rated 'AA-'api-227433089No ratings yet

- Hooked On Hydrocarbons: How Susceptible Are Gulf Sovereigns To Concentration Risk?Document9 pagesHooked On Hydrocarbons: How Susceptible Are Gulf Sovereigns To Concentration Risk?api-227433089No ratings yet

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York Joint Criteria TransitDocument7 pagesMetropolitan Transportation Authority, New York Joint Criteria Transitapi-227433089No ratings yet

- Japanese Corporates Hitch Growth Plans To Southeast Asian Infrastructure, But Face A Bumpy RideDocument14 pagesJapanese Corporates Hitch Growth Plans To Southeast Asian Infrastructure, But Face A Bumpy Rideapi-227433089No ratings yet

- How Is The Transition To An Exchange-Based Environment Affecting Health Insurers, Providers, and Consumers?Document5 pagesHow Is The Transition To An Exchange-Based Environment Affecting Health Insurers, Providers, and Consumers?api-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument16 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument7 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument10 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- 2014 Review of U.S. Municipal Water and Sewer Ratings: How They Correlate With Key Economic and Financial RatiosDocument12 pages2014 Review of U.S. Municipal Water and Sewer Ratings: How They Correlate With Key Economic and Financial Ratiosapi-227433089No ratings yet

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York Joint Criteria TransitDocument7 pagesMetropolitan Transportation Authority, New York Joint Criteria Transitapi-227433089No ratings yet

- California Governor's Fiscal 2015 May Budget Revision Proposal Highlights Good NewsDocument6 pagesCalifornia Governor's Fiscal 2015 May Budget Revision Proposal Highlights Good Newsapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument9 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument9 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- Report Highlights Qatari Banks' Expected Robust Profitability in 2014 Despite RisksDocument4 pagesReport Highlights Qatari Banks' Expected Robust Profitability in 2014 Despite Risksapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument7 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- Adding Skilled Labor To America's Melting Pot Would Heat Up U.S. Economic GrowthDocument17 pagesAdding Skilled Labor To America's Melting Pot Would Heat Up U.S. Economic Growthapi-227433089No ratings yet

- The Challenges of Medicaid Expansion Will Limit U.S. Health Insurers' Profitability in The Short TermDocument8 pagesThe Challenges of Medicaid Expansion Will Limit U.S. Health Insurers' Profitability in The Short Termapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument8 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- How "Abenomics" and Japan's First Private Airport Concession Mark The Beginning of The End For Self-Financing The Nation's Public InfrastructureDocument6 pagesHow "Abenomics" and Japan's First Private Airport Concession Mark The Beginning of The End For Self-Financing The Nation's Public Infrastructureapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument5 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument14 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- U.S. Corporate Flow of Funds in Fourth-Quarter 2013: Equity Valuations Surge As Capital Expenditures LagDocument12 pagesU.S. Corporate Flow of Funds in Fourth-Quarter 2013: Equity Valuations Surge As Capital Expenditures Lagapi-227433089No ratings yet

- Global Economic Outlook: Unfinished BusinessDocument22 pagesGlobal Economic Outlook: Unfinished Businessapi-227433089No ratings yet

- Recent Investor Discussions: U.S. Consumer Products Ratings Should Remain Stable in 2014 Amid Improved Consumer SpendingDocument6 pagesRecent Investor Discussions: U.S. Consumer Products Ratings Should Remain Stable in 2014 Amid Improved Consumer Spendingapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument5 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- Early Thoughts On The FDA's Move To Regulate E-Cigs: No Heavy Cost To E-Cig Sales, But Potential Cost To ManufacturersDocument4 pagesEarly Thoughts On The FDA's Move To Regulate E-Cigs: No Heavy Cost To E-Cig Sales, But Potential Cost To Manufacturersapi-227433089No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument6 pagesUntitledapi-227433089No ratings yet

- New Jersey's GO Rating Lowered To A+' On Continuing Structural Imbalance Outlook StableDocument6 pagesNew Jersey's GO Rating Lowered To A+' On Continuing Structural Imbalance Outlook Stableapi-227433089No ratings yet

- Investment Unit: Key Terms and ConceptsDocument3 pagesInvestment Unit: Key Terms and ConceptsnhNo ratings yet

- Estimating in Building Construction: Chapter 7 LaborDocument34 pagesEstimating in Building Construction: Chapter 7 LaborTayyab ZafarNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2016-2017 PDFDocument138 pagesAnnual Report 2016-2017 PDFPunita PandeyNo ratings yet

- Calculating future, present values of cash flows at different interest ratesDocument6 pagesCalculating future, present values of cash flows at different interest ratesSouvik NandiNo ratings yet

- Exim PolicyDocument11 pagesExim PolicyRohit Kumar100% (1)

- 2 Forex Question CciDocument50 pages2 Forex Question CciRavneet KaurNo ratings yet

- Student Loans Bursaries Grants and ScholarshipsDocument7 pagesStudent Loans Bursaries Grants and Scholarshipsapi-236008315No ratings yet

- Itr-1 Sahaj Indian Income Tax Return: Acknowledgement Number: Assessment Year: 2020-21Document8 pagesItr-1 Sahaj Indian Income Tax Return: Acknowledgement Number: Assessment Year: 2020-21MaheshNo ratings yet

- CAGR CalculatorDocument1 pageCAGR Calculatorsmallya100% (4)

- Mr. Kishore Biyani, Managing Director: Download ImageDocument32 pagesMr. Kishore Biyani, Managing Director: Download ImagedhruvkharbandaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 - Lecture 4 Protective Call & Covered Call Probelm Hatem Hassan ZakariaDocument8 pagesAssignment 1 - Lecture 4 Protective Call & Covered Call Probelm Hatem Hassan ZakariaHatem HassanNo ratings yet

- Key Economic Growth Indicators - CNN BusinessDocument7 pagesKey Economic Growth Indicators - CNN BusinessLNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Modeling and Computation in FinanceDocument4 pagesMathematical Modeling and Computation in FinanceĐạo Ninh ViệtNo ratings yet

- Exam TimetableDocument17 pagesExam Timetableninja980117No ratings yet

- Program Management Office (Pgmo) : Keane White PaperDocument19 pagesProgram Management Office (Pgmo) : Keane White PaperOsama A. AliNo ratings yet

- RBC US Dream HomeDocument36 pagesRBC US Dream HomeJuliano PereiraNo ratings yet

- Planning Fundamentals: Types, Process and ImportanceDocument236 pagesPlanning Fundamentals: Types, Process and Importancesanthosh prabhu mNo ratings yet

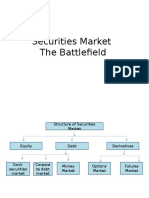

- Securities Market The BattlefieldDocument14 pagesSecurities Market The BattlefieldJagrityTalwarNo ratings yet

- SERPDocument2 pagesSERPBill BlackNo ratings yet

- MBA Financial Management AssignmentDocument4 pagesMBA Financial Management AssignmentRITU NANDAL 144No ratings yet

- DCB NiYO Card Terms and ConditionsDocument16 pagesDCB NiYO Card Terms and ConditionsShivran RoyNo ratings yet

- GSC SelfPrint TicketDocument1 pageGSC SelfPrint Ticketrizal.rahmanNo ratings yet

- Asm Chap 4 Bus 3382Document9 pagesAsm Chap 4 Bus 3382Đào ĐăngNo ratings yet