Professional Documents

Culture Documents

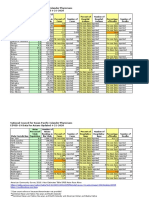

Better Outcomes Lower Costs FSG&GIH Spring 2012

Uploaded by

iggybau0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

244 views18 pagesFSG is a nonprofit consulting firm specializing in strategy, evaluation, and research. Atul gawande, MD, is a surgeon, writer, and public health researcher. He has won numerous awards for his research on health care.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentFSG is a nonprofit consulting firm specializing in strategy, evaluation, and research. Atul gawande, MD, is a surgeon, writer, and public health researcher. He has won numerous awards for his research on health care.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

244 views18 pagesBetter Outcomes Lower Costs FSG&GIH Spring 2012

Uploaded by

iggybauFSG is a nonprofit consulting firm specializing in strategy, evaluation, and research. Atul gawande, MD, is a surgeon, writer, and public health researcher. He has won numerous awards for his research on health care.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 18

Report Title | 1

Better Outcomes, Lower Costs:

How Community-Based Funders

Can Transform U.S. Health Care

A Conversation with Dr. Atul Gawande

Mark R. Kramer

Spring 2012

Boston | Geneva | Mumbai | San Francisco | Seattle | Washington | www.fsg.org

In association with

Discovering better ways to

solve social problems

FSG is a nonprofit consulting firm specializing in strategy, evaluation, and research.

Our international teams work across all sectors by partnering with corporations,

foundations, school systems, nonprofits, and governments in every region of the globe.

Our goal is to help companies and organizationsindividually and collectivelyachieve

greater social change.

Working with many of the worlds leading corporations, nonprofit organizations, and

charitable foundations, FSG has completed more than 400 consulting engagements

around the world, produced dozens of research reports, published influential articles in

Harvard Business Review and Stanford Social Innovation Review, and has been featured

in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Economist, Financial Times, BusinessWeek,

Fast Company, Worth, and NPR, among others.

Learn more at www.fsg.org.

1

Authors

Atul Gawande, MD, is a surgeon, writer, and public health researcher. He practices

general and endocrine surgery at Brigham and Womens Hospital in Boston. He is also

Associate Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School and Associate Professor in

the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard School of Public

Health. He is the author of three best-selling books and has been a staff writer for the

New Yorker magazine since 1998. He has won numerous awards for his research on

health care, including a MacArthur Award, and was selected by TIME magazine as one of

the worlds top 100 influential thinkers.

Mark R. Kramer is a co-founder and managing director of FSG, a global social impact

consulting firm with offices in the United States, Europe and Asia. He is also a co-founder

and the initial Board Chair of the Center for Effective Philanthropy and a Senior Fellow at

the J ohn F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He is the co-author,

with Professor Michael Porter, of four influential articles in Harvard Business Review on

philanthropic strategy and the role of corporations in society, and a regular contributor to

Stanford Social Innovation Review on topics such as catalytic philanthropy, collective

impact, and impact investing.

About Grantmakers in Health

Grantmakers In Health is a nonprofit, educational organization dedicated to helping

foundations and corporate giving programs improve the health of all people. Its mission is

to foster communication and collaboration among grantmakers and others, and to help

strengthen the grantmaking community's knowledge, skills, and effectiveness.

2

Introduction

Over the past three years, Dr. Atul Gawandes articles and books have profoundly altered thinking about

the U.S. health care system. Although he has not written specifically about the role of philanthropy, his

research demonstrates that the cost and quality of health care in the United States are heavily influenced

by local practices, and can be profoundly influenced by community-based efforts with modest levels of

funding. As a result, we see a tremendous philanthropic opportunity that has been almost entirely

overlooked: hundreds of health foundations, community foundations, and corporate or family foundations

are ideally positioned to lead a national movement to transform the U.S. health care system by lowering

costs and improving patient outcomes in their local communities.

Most smaller, local funders have steered clear of health

care reform because of the vast magnitude of health care

spending and the vituperative national controversy over

health care policy. In this, they have conflated access to

care with the cost and quality of care. Providing access to

care by addressing the needs of the uninsured is a costly and controversial national issue that cannot

easily be addressed at local levels. However, Dr. Gawandes research demonstrates that the costs and

quality of care are driven by local behaviors that vary dramatically from one community to the next. Here,

there is surprisingly little correlation between the cost of care and the quality of patient outcomes. Instead,

Dr. Gawande cites many examples of simple and inexpensive changes in practice within local

communities that have produced dramatic improvements in patient care and reductions in cost.

We often refer to our health care system, but in reality it does not function like a system at all. Health

care today has become so complex and fragmented that each participant does his or her own part without

any awareness or control over how his or her choices affect the larger system overall. Perverse financial

incentives prevent any single participant from making substantial improvements by acting alone, even if

the improvements serve the interests of the patients, the

public, the payer, and the provider. We have no localized

data that can give us an accurate understanding of how

patients are cared for in our community and whether our

practices are better or worse than other, similar

communities. There are no neutral coordinating councils that can bring all relevant players together to

gather the necessary data and solve problems collectively. As a result, the system is paralyzed.

Innovations that save lives and money do not spread from one provider or community to the next.

Improvements that are neither controversial nor costly remain stymied.

We see a tremendous philanthropic

opportunity that has been almost

entirely overlooked.

Innovations that save lives and money

do not spread from one provider or

community to the next.

3

One solution that has worked in multiple

communities across the country is the

formation of a coordinating council that

includes CEO-level representatives and key

local influencers from all major organizations

affected by medical care in the community:

doctors, hospital administrators, insurers,

government agencies, and business leaders.

This council must identify a specific problem

to be tackled, such as improving end-of-life

care or reducing post-surgical infections or

excessive testing; conduct local research to

analyze the problem; identify solutions that

have been implemented elsewhere or that

might be piloted locally; test and refine these

solutions; and then drive implementation

through all relevant organizations in the

community.

In this, health care is no different from many other large-scale social problems we face, such as education

reform or childhood obesity. Lasting solutions must come not from any single magical solution, but from

bringing together dozens of local players to set a common agenda, gather shared data about the

problem, develop mutually reinforcing activities, and maintain ongoing communication supported by a

backbone organization. This is an approach we call collective impact, and it has achieved demonstrable

success on a wide variety of issues.

1

Community-based funders across the United States, such as community foundations, health foundations,

and family or corporate foundations, have the stature and resources to organize and fund collective

impact health care initiatives in their communities, and to share their learning with other communities

across the country. It is precisely because of their local focus and convening power that regional funders

can play this crucial role in ways that national funders and government agencies cannot. Individually,

these foundations have the opportunity to make a profound and lasting impact on the health of their

communities; together, they have the opportunity to create a national movement to achieve better

outcomes at lower cost.

In the following conversation, Mark Kramer and Dr. Gawande discuss this untapped potential for

community-based funders to transform the cost and quality of health care in the United States.

1

See J ohn Kania and Mark Kramer, Collective Impact, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2011.

4

National Access vs. Local Cost and Quality

Mark: Good morning, Atul, and thank you for taking the time for this interview. I have been deeply

influenced by your research and writing over the last few years, and through our work with

foundations at FSG, I have come to believe that there is a tremendous opportunity for community

philanthropy that is implicit in your writing. You have never explicitly written about that

opportunity, but that is what Id like to discuss today. First of all, let me ask you: Why is it that

most private foundations believe that health care reform is too large and controversial an issue for

them to tackle?

Atul: When we think about the health care troubles in our

communities, we first tend to think about our uninsured

populations. And to help the uninsured, we do need

national solutions. Weve been debating different solutions

for access to care for the past four or five decades: single

payer, multi-payer, private coverage, and so on. The media attention on that debate has led us to think

that all of the solutions for making our health care systems better have to come from Washington. I think

thats a big mistake. Helping to make health care systems better at dealing with the cost of treatment and

the quality of patient outcomesthat turns out to be much more about local systems of careand those

issues arent controversial at all. It is hard to find anyone who would object to fewer post-surgical deaths,

better management of chronic disease, or honoring patients wishes at the end of lifeespecially when

those improvements also reduce cost.

The Disconnect Between Cost and Quality: A Tale of Two Cities

Mark: You say that, by working locally, you can improve outcomes and lower cost at the same

time. That seems completely counterintuitive. Dont we need to spend more money on health

care to get better patient outcomes?

Atul: Not at all. There is a wide swath of difference in cost and

quality among hospitals in different communities. The variations

fit a typical bell curve, with most doctors and hospitals in the

mediocre middle. The really unnerving thing, though, is that our

curve for quality doesnt match our curve for cost. The most

expensive places in the country are not necessarily getting the best patient outcomes, and vice versa. On

the contrary, we see very consistently that the places getting the best results are usually in the bottom

half of the cost curve.

Ill give you an example: McAllen, Texas, is the second most expensive place in the country for Medicare

patients. They are a very poor community, yet they spend more than $16,000 per person per year. Of

The cost of treatment and the quality of

patient outcomes turns out to be about

local systems of care.

The places getting the best results

are usually in the bottom half of

the cost curve.

5

course, theyve got significant health care problems: theres a lot of diabetes, obesity, and alcohol abuse,

and there are a lot of illegal immigrants that are stressing the public health systems. At first, I thought that

explained the high costs, but then you go a few hundred miles up the border to El Paso, Texas, which is

just as poor, with exactly the same demographics and health problems, and you find they spend only half

as much per person. And the really astonishing thing is that, to the extent that we have metrics, El Paso

has a higher quality of care across their half-dozen hospitals compared to the half-dozen hospitals in

McAllen that are spending an average of twice as much per patient. These two places with very similar

challenges are getting remarkably different results.

2

Mark: How do you explain the difference?

Atul: In McAllen what I saw, for better or for worse, was a medical community that made the profit-making

side of medicine a very high priority. Theres always a balance between making medicine work as a

business and meeting the needs of the community. But focusing on profitability can lead you to

overemphasize certain tests and procedures and underemphasize other areas, such as primary care,

mental health, and geriatric care, because theyre not as profitable. El Paso, on the other hand, seemed

to have a medical culture that puts at least some more emphasis on meeting patient needs regardless of

profitability.

All medicine is like all politics: it is local. A few key community leaders shape the way medicine is

practiced and the kind of health care their community gets. Its not just the medical community that

determines how medicine is practiced, but also the major local employers who set expectations about

acceptable levels of health care costs and quality, and the local and state governments that hold people

accountable and measure what is actually going on. Its the local community that is fundamentally

responsible for the success or failure of its own health care system.

Community Efforts that Work: Success Stories

Mark: Can you give me some examples of communities that have been able to improve patient

outcomes or lower costs through entirely local efforts?

Atul: Absolutely. Cedar Rapids, Iowa, formed a coalition of local employers and leaders in the medical

community to look at the use of CT scans. First of all, no one actually knew how many CT scans were

done in a year. We know that, at a national level, CT scans are way overused: there are 62 million scans

a year in the United States. But its an abstract, meaningless number that doesnt seem relevant to

someone in Cedar Rapids. You need to know what is happening in your own community. And it turns out

2

For a more detailed description of the contrast between these two cities, see Atul Gawande, The Cost Conundrum, The

New Yorker, J une 1, 2009.

6

that its very hard to get that answer, because each hospital and medical practice keeps separate

records.

It took three months of really digging, and what they

found out was that there were 52,000 CT scans in a

single year in Cedar Rapids, a community of only

300,000 people. The doctors were astonished at the

number, and they were not happy about it. They

immediately set a goal of reducing unnecessary CT

scans. For example, 10,000 of the scans were for headachesof which only about a dozen patients had

any abnormality, or one-tenth of one percent. In fact, most patients really didnt meet the criteria for

needing a CT scan. Plus, all that radiation exposure probably increased the risk of certain kinds of

cancers. Perhaps malpractice litigation was one reason why the doctors were doing so many of these

scans. But once the community got together across disciplinesincluding citizens and employersto ask

hard questions with real data, they were able to arrive at guidelines that would make much more judicious

use of these scans.

Or take another example: In 1991, for whatever

reason, the local leadership in La Crosse,

Wisconsin recognized that the way we care for

people with terminal illness in America doesnt

meet their needs. We are not great at making

sure people dont suffer, that theyre able to have

more control over their lives as they come to an

end, that they dont die in an intensive care unit

with invasive technologies that not everybody

wants. What they recognized was that people

needed to make these choices ahead of time,

before they arrived at an emergency room in

complete crisis. And so the doctors in La Crosse

were encouraged to have these conversations

with their patients during routine check-ups or,

even more importantly, when people were first

admitted to a nursing home or hospital. As a

result, by 1996, the number of people admitted

to the hospital with living wills that described

their desires for end-of-life care increased from

15 percent to 85 percent.

This simple change reduced the cost of end-of-life care by half, and La Crosse became one of the lowest-

cost places in the country for end-of-life carewhich is a large portion of the total costs of medical care.

And they did it with no sign whatsoever that the longevity of people in that community has been harmed in

All medicine is like all politics: it is local. A

few key community leaders shape the way

medicine is practiced and the kind of health

care their community gets.

7

any way. Despite average rates of obesity and smoking, the life expectancy of La Crosse residents

outpaces the national mean by a year. And other studies have shown that people who have these

discussions and choose palliative care not only reduce their hospital stays by half, they have better

quality of life at the end of life, and they live 25 percent longer.

3

Mark: Its remarkable that just bringing community leaders together to focus on a specific

problem, collecting data about what is really happening at a local level, and encouraging simple

changes in local behavior can bring about such dramatic cost savings, while also improving

health outcomes. The example of La Crosse

doesnt involve anything more than an outreach

campaign to get people to fill out a form, yet it has

a large impact on costs and quality. It seems like

an especially important lesson for community-

based foundations, because convening community leaders, raising awareness about an issue,

and funding local research studies are all activities that come naturally to them and require very

modest levels of funding. It suggests that even small regional foundations could have a big

impact on health care in their communitiesand yet we see smaller funders often steer clear of

health care issues because they see the vast amounts of money spent in the health care system

and think that there is no place $100,000 or even $1 million could make much difference.

Atul: I can give you an even more dramatic example of the impact a small amount of money can have.

We were asked to take on a project to reduce deaths in surgery. At first, I thought the answer would be

about training programs, licensing requirements, or shifting patients to high-volume hospitals. But what

we learned was that a simple checklist of about a dozen things that surgeons could do in the operating

room has a tremendous impact. So, we worked with Boeing to develop a two-minute checklist based on

the checklists that pilots use before takeoff. It covered simple things like making sure antibiotics were

given appropriately, blood was available, and everybody on the team knew each others name and

understood the plan before a knife ever hit the skin.

We tested it into eight hospitals around the world,

and we deliberately included poor hospitals in rural

Tanzania, Delhi, Manila, and J ordan, as well as

some of the top hospitals in the world, such as the

University of Washington in Seattle, Toronto General Hospital, and St. Marys Hospital in London. Every

single hospital reduced its complication rate by more than 30 percent. The average reduction in

complication was 36 percent. The average reduction in post-surgical deaths was 47 percent.

And the checklist costs nothing to use. Hundreds of billions of dollars are spent every year on new

equipment or drugs that dont begin to have the life-saving impact of this simple checklist. The whole

3

The La Crosse example is described in Atul Gawande, Letting Go, The New Yorker, J uly 26, 2010.

Even small regional foundations

can have a big impact on health

care in their communities.

The whole project probably cost about a

million dollars and it is saving hundreds

of thousands of lives every year.

8

project probably cost about a million dollars for us to design and test, and it is saving hundreds of

thousands of lives every year.

4

Promoting Adoption: The Culture Barrier

Mark: The checklist seems so simple, and has such stunning results, that one would think it

would be picked up and implemented everywhere immediately. What has adoption been like?

Atul: Its tremendously frustrating. We recognize that this could be saving thousands of lives, and yet its

being used in less than one-third of U.S. hospitalsand even in the hospitals that picked it up, we know

implementation is quite variable.

It took me a while to realize why professionals would not want to try the checklist even when its been

demonstrated that using it helps people. And what I realized is that the checklist contains a set of values.

Those values are first, humility: recognizing that youa surgeon, anesthesiologist, or nursemake

mistakes. Thats a starting point not everybody is ready to embrace. The second value is teamwork: the

belief that the wisdom of a roomful of people is greater than just the wisdom of the top dog. And the third

value is self-discipline: the belief that doing things in a very simple, straightforward, regimented way, like

on an airplane or a pit crew for a racecar, doesnt mean dumbing down.

The challenge is in changing the medical culture. We surveyed surgical teams three months after trying

the checklist; 80 percent said they thought it made surgery easier and safer for patients and that they had

actually seen it catch an error. But 20 percent still hated it. They thought it was a waste of time: they didnt

think they needed it. Then we asked them, if you were having an operation, would you want the checklist?

Ninety-three percent of them wanted it.

Mark: Can local foundations help in spreading adoption?

Atul: Yes. For example, we got backing from a small family foundation to help us launch an effort in one

state, South Carolina, where were measuring infections, deaths in surgery, and other failures of

operations, and then implementing the checklist into all 67 of their hospitals in partnership with their

hospital association. It takes working at that local level to bring people on board in a field where there is

resistance to change. And we need local funding partners in every city and state if we are going to spread

the adoption of these improvements.

4

See Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto, Metropolitan Books, 2009

9

Perverse Payment Incentives

Mark: It seems like no individual doctor, hospital, or insurer can bring about these kinds of

changes. Instead, a neutral party, like a foundation, has to bring all the parties together to solve

the problem collectively. In fact, there are often perverse payment incentives that discourage

improvements in care because the savings to one party come at the expense of another.

Atul: Right. Take a topic like asthma in the inner city, a very big problem affecting children. Childrens

Hospital here in Boston recognized the problem and decided to start a project focusing on the kids with

the most severe asthma attacks, who came to

the emergency room or were admitted to the

hospital. They said, first of all, lets identify what

great care looks like for those kids. And

essentially they came up with a checklist: a half-

dozen things that can make a big difference,

ranging from home visits to make sure there was

no mold and mite infestation in the house to

making sure a nurse checked in and the family

had actually filled their prescriptions for inhalers

and knew how to use them. They even bought

families vacuum cleaners, because they found a

quarter of families in the inner-city areas did not

have them. After one year, the number of

asthma admissions to the hospital emergency

room dropped 80 percent. It was a stunning

success. But guess what the number one source

of revenue for Childrens Hospital of Boston is?

Asthma admissions. Thats how the hospital makes its dollars. And if a place has to choose between

doing the right thing and going bankrupt, thats not much of a choice at all.

So even though Childrens found a solution, they

couldnt implement it without changing the

reimbursement system. They went to their major

insurersMedicaid and Blue Crossand said, heres

what great care looks like. Weve proved it, and it can

save you a lot of money, because the extra cost of

these services is a lot less than the cost of hospital admissions. But we need to renegotiate our contract

so that were paid for providing great care even though these kids arent being admitted to the hospital.

And they worked out a deal. Neither the insurer nor the hospital could have solved the problem alone.

But, working together, they recognized a problem, they found a solution, and then they addressed it. This

is what a great coalition can do at the community level in a way that youll never invent in Washington.

The hospital cant do it on its own, the

community cant do it on its own, and the

insurer cant do it on its own. It can only

happen through collaboration.

10

Mark: So you are saying that the hospital cant do it on its own, the community cant do it on its

own, and the insurer cant do it on its own. It can only happen through collaboration.

Atul: Thats right, and even though Childrens Hospital renegotiated for themselves, that doesnt mean

that asthma care for kids who go to other hospitals in the community is going to change, let alone kids in

other communities across the country. Heres a solution that could save significant dollars for the health

care system and save kids lives, but its not going to happen unless we focus on the larger picture. That

takes collaboration, and the problem is that those kinds of collaborations almost never happen. It takes a

community leader to bring the medical, business, and government communities together to find solutions

and figure out how to fund them.

The Urgency of Impact

Mark: It seems as though this is a massive challenge for our countryand that there is a real

urgency for funders to take action.

Atul: Absolutely. The thing that is so unnerving about

tackling this problem is that our time horizon is short. Well

never solve the problem of the uninsured until we get costs

under control, and that means improving the quality of care

and not wasting resources. Were going to bankrupt our state

governments within seven to nine years if health care costs

continue to rise at the current rate. We are going to continue to kill 150,000 people a year just from

complications of surgery. Employers in our communities are going to watch their health care costs go

from 10 percent to upwards of 17 percent. We are heading to a point where 20 percent of our economy

goes to health care, and we know a substantial portion of that investment is not providing high quality

and that these are resources we need to go to other urgent needs like education or energy. This issue is

fundamental. If America is to be a prosperous nation in the future, then getting the health care system

under control is the mission and challenge of our time.

The Non-System System

Mark: So are you saying that instead of spending money on laboratory research about diseases,

or new equipment and hospital facilities, funders who want to improve health care in their

communities should be focused on helping different parts of the local system work better

together?

Atul: Thats right. We call these local health care systems, but theyre not really systems at all, they are

fragmented institutions filled with people doing isolated jobs, whether its in mental health or surgery or

If America is to be a prosperous nation

in the future, then getting the health

care system under control is the mission

and challenge of our time.

11

whatever. No one is in a position to see how the

system comes together, how it impacts people

economically, or because of issues of poor quality

and poor service. The truth of the matter is that the health of our community and the effect that we as

doctors and hospitals have on that health is invisible to most of us. I just do my surgery and feel like if Im

doing a good operation for the patients Im seeing, thats what I can do. I dont see what all of the different

surgeons are doing throughout the community and then what everybody else in the health care system is

doinghow many emergency room visits there are, how many infections there are, and whether were

making a difference.

So the investment we really need to make is in systems change. And changing systems of care is not

something that the National Institutes of Health is designed to do. But a community-based foundation can

make the invisible health care system become a visible one by collecting data, and just by doing that,

people begin to act differently. The non-system starts to become more of a system and is better able to

solve problems for the community.

The reality today is that the complexity of care is at the point where innovation to improve systems of

careeven through simple things like checklistsrequires research, and that type of research is just not

getting funded.

The Role of Funders: Collective Impact in Health care

Mark: What fascinates me about this is how it relates to

other work that FSG has been doing on a completely

different set of issues. Whether it is the juvenile justice

system in New York state, secondary education in Seattle,

diabetes care in India, or impoverished cocoa farmers in

Cote DIvoire, again and again we are finding that the

solution to major social problems doesnt lie in some new

program or innovation. Each of these problems is the result

of a non-system system, where the different actors

government agencies, nonprofits, foundations, and

corporationsare each acting independently, without any sense of how their efforts fit together,

and the result is disastrous for the people who are

supposed to be helped.

We increasingly see that the most powerful role funders

can play is to help convene, coordinate, and align the

different participants so they can agree on a common

agenda, develop a shared measurement system so that all participants are using the same data

to track results, promote continuous communication and mutually reinforcing activities, and,

We call these local health care systems,

but theyre not really systems at all.

FSGs work on collective impact seems to

fit exactly the process you are describing

in health care reform.

12

above all, provide an infrastructurewhat we call a backbone organizationto facilitate

progress and hold the initiative together. Its an approach we call collective impact, and weve

developed considerable research about how funders can initiate and sustain these efforts.

5

It

really seems to fit exactly the process you are describing in health care reform.

But lets get more specific: If you were speaking to a group of smaller community-based funders,

what would you advise them to do?

Atul: I would tell them that what we need to make health reform succeed is to build a community that

actually demonstrably raises the quality and safety of care and lowers its costs, without harming a soul.

For a foundation to make a difference in helping a community do that, I think there are four places they

can make a contributionand none of them cost large amounts of money.

Collecting the data is where I would start. Show the community a snapshot of how their health care

system works and where the costs are. Dont make it overly complex; make it simple enough that some

basic questions can be answered, like how many people are coming into the emergency room, and why?

Knowing data at the national level, like the 62 million CT scans, isnt meaningful to drive local change.

Some states are collecting local data, but their databases are generally at least four years old. You cant

drive a car when the speedometer tells you how fast you were going four years ago. And you need to

keep the data current to guide communities about how well theyre doing, where new problems are

emerging, and whether theyre making progress over time.

What it takes is for the funders to bring together the

major hospitals, insurers, and medical groups to share

their data. Often they are reluctant to collaborate, but

that can be brokered. Its not hugely expensive.

Sometimes it just takes one persistent person. I saw one

family physician collect the data by foot: He walked to

the data departments of the three local hospitals, got

permission to put the data on his laptop, figured out how to mesh it together, and in six months he had a

community-wide snapshot of how many people were visiting the emergency room, how many imaging

studies were being ordered, and so on.

Once you have the data, then I would invest in having the stakeholders come together to set priorities.

The data tells you where the problems are; now we need to agree on which problems were going to

tackle. Id want to attack the big killers that are also the sources of high cost and low quality. So, Id want

to have safer surgical care; safer childbirth; better primary care; improvements in end-of-life care for the

terminally ill patient; a way to ensure were not overusing imaging that is not only expensive but exposes

5

See J ohn Kania and Mark Kramer, Collective Impact, Stanford Social innovation Review, Winter 2011. See also

Hanleybrown, Kania, & Kramer, Channeling Change, Stanford Social innovation Review online (2012), and other

resources about collective impact at www.FSG.org.

What we need to make health reform

succeed is to build a community that

demonstrably raises the quality and safety

of care and lowers its costs, without

harming a soul.

13

people to potentially harmful radiation. You cant do

it all at once, but any one of these areas will have a

big impact on the health of the community.

This is especially true in smaller communities. My

sense is that in communities of up to about 500,000

people, the health care system is something that people can get their arms around. You find there are a

few leaders that people look to as setting the values that permeate the community. You can bring those

people together into a workable group that can make priorities clear and then begin to tackle them.

The third step is innovation. We need to foster and support the innovators that can work at the local

levelor even at a national levelto find solutions for these sets of system-wide problems. Investing in

system solutions is no less complex and no less necessary than investing in a cancer cure. A lot of

solutions are already there, but they arent yet ready to use off the shelf.

If you want to tackle end-of-life care, for example, La Crosse has already succeeded. Well, what exactly

did they succeed at doing? Whats the end-of-life tool kit that I can bring into my community? We need to

invest in the generation of those tool kits. This isnt expensive research, like developing a new cure for a

disease. Sometimes the solution is as simple as a checklist, or buying vacuum cleaners. Its the kind of

research any funder could afford to support, but right now, we underinvest in these things. We think they

should already exist, but the reality is that they dont, and it takes work to make a tool kit that any

community can really use well. There are people who are ready to take on these challenges, but we

arent funding them.

Then the fourth component is implementation. That takes funding, too. I mentioned the family foundation

that is funding the implementation of the pre-surgery checklist in South Carolina. That is a sizable

projectabout $4 million over three yearsbut that is to implement the checklist in 67 hospitals across

the state and rigorously track the results, so the cost works out to about $60,000 per hospital. Its not a lot

of money to reduce post-surgical deaths by large numbers.

My own team is focused on all four of these work streams, but the shocking thing to me is how hard it is to

fund this work. We are small, but our first priority is to make sure our surgical checklist is implemented

nationwide, and then worldwide. But I also want to build a portfolio of solutions for communities in

childbirth, end-of-life care, and primary care. We

already know how to make the checklist for the 15

things that should happen to make every childbirth

safer for the mom and the babyand, by the way, to

reduce costs. We could do the same thing for terminally ill patients or hospital discharges. We want to

create a portfolio of tools that communities can use right off the shelf.

Investing in system solutions is no less

complex and no less necessary than

investing in a cancer cure.

The shocking thing to me is how

hard it is to fund this work.

14

From the Local to the National: Sharing Solutions

Mark: It seems like a few individual communities are finding solutions for a few specific problems,

but they arent learning from each other to spread best practices nationally.

Atul: I think theres no question that communities arent learning from each other. We held a conference

in Washington, D.C., bringing together about a dozen communities that had lower costs for Medicare

patients and were also in the top quartile of quality on the metrics we have available. We asked them to

bring business leaders, hospital heads, and others from different parts of the community to talk about

what their own numbers and data looked like. The first thing we found is that the communities had never

seen their data in comparison to the othersthey hadnt realized how differently they were doing things

from other communities.

We also found that these communities were much more likely to have stakeholders who got together

regularly to look at the quality of health care in the community. In places like Grand J unction, Colorado,

for example, theres a coalition of physicians, the head of the major community insurance plan, and the

heads of the local hospitals who meet regularly to ask how theyre doing in terms of quality in primary

care. In essence, they put together a health care

information exchange and set goals for what they were

going to accomplish in the community.

So the real opportunity is that many communities are

each doing something really well. They bring

stakeholders together, set priorities, and collect data on some key measures. One community might be

strengthening primary care, another might be reducing unnecessary back surgeries, a third might make

surgery safer. But no community has a full portfolio of these projects that address all the really important

dimensions of health in their community. None of these projects are easy, but I think that such a portfolio

can be created at the community level. God knows it cant be done in Washington.

Mark: It seems to me that this is an opportunity for community-based foundations as wellto

share information with each other about successful initiatives in their local communities and so

spread these isolated projects into a national movement for comprehensive health care reform.

Atul: I agree. Its an exciting thought. It will be challenging because you are asking us in the medical

community to think of ourselves as citizens responsible for the health and economic well-being of our

community as a whole, not just for our individual pieces of the puzzle. But foundations have the

leadership potential and the resources to make this happen. It is a role that community-based

foundationseven those with modest resourcescan play extremely well. In fact, it is precisely because

they are focused on their local communities that they can play this role better than national foundations,

and certainly better than government ever could. Most funders havent yet recognized it, but improving

the quality and lowering the cost of U.S. health care is a uniquely powerful place for community

philanthropy.

Improving the quality and lowering the cost

of U.S. health care is a uniquely powerful

place for community philanthropy.

For questions or comments on this report, please contact:

Mark Kramer

Managing Director

Mark.Kramer@fsg.org

Better Outcomes, Lower Costs: How Community-Based Funders

Can Transform U.S. Health Care by FSG is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Permissions beyond

the scope of this license may be available at www.fsg.org.

FSG

FSG is a nonprofit consulting firm specializing in strategy, evaluation, and research, founded in 2000 as

Foundation Strategy Group and celebrating a decade of global social impact. Today, FSG works across

sectors in every region of the worldpartnering with foundations, corporations, nonprofits, and

governments to develop more effective solutions to the worlds most challenging issues.

www.fsg.org

Boston | Geneva | Mumbai | San Francisco | Seattle | Washington | www.fsg.org

You might also like

- Group Insurance Q-ADocument9 pagesGroup Insurance Q-Apkgarg_iitkgpNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Care and Human Rights - NHRC IndiaDocument472 pagesMental Health Care and Human Rights - NHRC IndiaVaishnavi JayakumarNo ratings yet

- 10 Ideas For Healthcare, 2011Document36 pages10 Ideas For Healthcare, 2011Roosevelt Campus NetworkNo ratings yet

- Medical Device RegulationDocument6 pagesMedical Device RegulationAnonymous iqoU1mt100% (2)

- The Quality Cure: How Focusing on Health Care Quality Can Save Your Life and Lower Spending TooFrom EverandThe Quality Cure: How Focusing on Health Care Quality Can Save Your Life and Lower Spending TooNo ratings yet

- Advocacy KitDocument72 pagesAdvocacy KitDritan ZiuNo ratings yet

- Top 50 Deficiencies in CTD DossiersDocument7 pagesTop 50 Deficiencies in CTD Dossiersyukon5No ratings yet

- Douglas Holmes - EGov - E-Business Strategies For Government-Nicholas Brealey Publishing (2001)Document339 pagesDouglas Holmes - EGov - E-Business Strategies For Government-Nicholas Brealey Publishing (2001)gecko4No ratings yet

- Guidelines For Mapping LinksDocument2 pagesGuidelines For Mapping Linksmuzammil21_adNo ratings yet

- Health Care Equity Tool Kit for Developing Winning PolicyDocument25 pagesHealth Care Equity Tool Kit for Developing Winning PolicyDenden Alicias100% (1)

- Futurescan 2021–2026: Health Care Trends and ImplicationsFrom EverandFuturescan 2021–2026: Health Care Trends and ImplicationsNo ratings yet

- Social Media and NursingDocument3 pagesSocial Media and Nursinggideon mbathaNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Public HealthDocument312 pagesEvidence-Based Public HealthBudi Lamaka100% (7)

- Social Factors Influencing Individual and Population Health - EditedDocument6 pagesSocial Factors Influencing Individual and Population Health - EditedOkoth OluochNo ratings yet

- Risk Management ProcessesDocument32 pagesRisk Management ProcessesAndri Bendary HariyantoNo ratings yet

- Health on Demand: Insider Tips to Prevent Illness and Optimize Your Care in the Digital Age of MedicineFrom EverandHealth on Demand: Insider Tips to Prevent Illness and Optimize Your Care in the Digital Age of MedicineNo ratings yet

- Making the Healthcare Shift: The Transformation to Consumer-CentricityFrom EverandMaking the Healthcare Shift: The Transformation to Consumer-CentricityNo ratings yet

- Ronald Garcia, PHD: Stanford University School of MedicineDocument16 pagesRonald Garcia, PHD: Stanford University School of MedicineapamsaNo ratings yet

- Community Organizing For Health Care An Analysis of The Process 2Document20 pagesCommunity Organizing For Health Care An Analysis of The Process 2api-661484626No ratings yet

- Hsci 6250Document4 pagesHsci 6250api-642711495No ratings yet

- Module 4 2Document4 pagesModule 4 2api-642701476No ratings yet

- SDOH WorkbookDocument116 pagesSDOH WorkbookLancelot du LacNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument9 pagesAssignmentKamruzzaman PrinceNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Universal Health Care SystemDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Universal Health Care Systemaflbrpwan100% (1)

- Community Health Workers Promote Civic Engagement and Organizational Capacity To Impact PolicyDocument13 pagesCommunity Health Workers Promote Civic Engagement and Organizational Capacity To Impact Policygujjar gujjarNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Research Paper On Health Care ReformDocument7 pagesHow To Write A Research Paper On Health Care Reformlyn0l1gamop2No ratings yet

- Research Paper On Health Care ReformDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Health Care Reformgz7vhnpe100% (1)

- Innovate, Co-Operate To Improve Health Services For CanadiansLet's Be More Than A Nation of Pilot Projects'by Kimberlyn McGrailDocument2 pagesInnovate, Co-Operate To Improve Health Services For CanadiansLet's Be More Than A Nation of Pilot Projects'by Kimberlyn McGrailEvidenceNetwork.caNo ratings yet

- Healthy Communities Advocacy PaperDocument3 pagesHealthy Communities Advocacy PaperPatricia SumayaoNo ratings yet

- 2008 Annual ReportDocument36 pages2008 Annual ReportVir NaffaNo ratings yet

- Policy PaperDocument6 pagesPolicy Paperapi-338528310No ratings yet

- Argument and ReasonDocument4 pagesArgument and ReasonVidyaa IndiaNo ratings yet

- Community Health Term PaperDocument7 pagesCommunity Health Term Paperafmzmajcevielt100% (1)

- Research Paper Topics On Health Care ManagementDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics On Health Care ManagementafeatoxmoNo ratings yet

- 10 Ideas For Healthcare, 2012Document32 pages10 Ideas For Healthcare, 2012Roosevelt Campus NetworkNo ratings yet

- Health Care Management Research Paper TopicsDocument9 pagesHealth Care Management Research Paper Topicscapz4pp5100% (1)

- Precision Community Health: Four Innovations for Well-beingFrom EverandPrecision Community Health: Four Innovations for Well-beingNo ratings yet

- Shea Issue 2 Article For WebsiteDocument1 pageShea Issue 2 Article For Websiteapi-400507461No ratings yet

- Poverty and Health Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesPoverty and Health Literature Reviewafmzfvlopbchbe100% (1)

- Greymatter January2017Document8 pagesGreymatter January2017sNo ratings yet

- Social Justice Project LetterDocument4 pagesSocial Justice Project Letterapi-680261058No ratings yet

- Research Paper On Health Care PDFDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Health Care PDFefkm3yz9100% (1)

- Research Paper On Social ServicesDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Social Servicesafmbvvkxy100% (1)

- Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide For Health and Social Scientists.: Sheldon Cohen, Lynn Underwood, Benjamin Gottlieb (Eds)Document12 pagesSocial Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide For Health and Social Scientists.: Sheldon Cohen, Lynn Underwood, Benjamin Gottlieb (Eds)ilham rosyadiNo ratings yet

- Community Health Factors and Health DisparitiesDocument7 pagesCommunity Health Factors and Health Disparitiesshreeguru8No ratings yet

- Beyond The Four Walls ReportDocument85 pagesBeyond The Four Walls ReportMaine Trust For Local NewsNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics Social WorkDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Topics Social Workvehysad1s1w3100% (1)

- Policy Impact PaperDocument7 pagesPolicy Impact Paperapi-384152992No ratings yet

- DS 331Document9 pagesDS 331chris fwe fweNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Economic Research Paper TopicsDocument4 pagesHealthcare Economic Research Paper Topicsafmcsvatc100% (1)

- Accountable Care Organizations: Your Guide to Strategy, Design, and ImplementationFrom EverandAccountable Care Organizations: Your Guide to Strategy, Design, and ImplementationNo ratings yet

- Medicine Hat Poverty Reduction ReportDocument98 pagesMedicine Hat Poverty Reduction ReportMike BrownNo ratings yet

- Political, Ethical, and Economical Influences On Health As You Examined in Week 1, The Disparity of Available Health Care StaffingDocument2 pagesPolitical, Ethical, and Economical Influences On Health As You Examined in Week 1, The Disparity of Available Health Care Staffingquality writersNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Application SWDocument6 pagesModule 4 Application SWapi-701091243No ratings yet

- Fresh Medicine: How to Fix, Reform, and Build a Sustainable Health Care SystemFrom EverandFresh Medicine: How to Fix, Reform, and Build a Sustainable Health Care SystemNo ratings yet

- Health Reform without Side Effects: Making Markets Work for Individual Health InsuranceFrom EverandHealth Reform without Side Effects: Making Markets Work for Individual Health InsuranceNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement About Social WorkersDocument5 pagesThesis Statement About Social Workerskimberlybergermurrieta100% (2)

- Term Paper On Health Care ReformDocument6 pagesTerm Paper On Health Care Reformdrnpguwgf100% (1)

- Dissertation Global HealthDocument7 pagesDissertation Global HealthBuyingCollegePapersPittsburgh100% (1)

- Thesis Statement On Health Care ReformDocument6 pagesThesis Statement On Health Care Reformdwns3cx2100% (2)

- Community Participation DissertationDocument4 pagesCommunity Participation DissertationWriteMyStatisticsPaperNewOrleans100% (1)

- Good Health Care Topics For Research PaperDocument4 pagesGood Health Care Topics For Research Paperlzpyreqhf100% (1)

- 452Document11 pages452ashNo ratings yet

- Healthy Behaviors Issue BriefDocument48 pagesHealthy Behaviors Issue BriefEliza DNNo ratings yet

- Boston Mayor Executive Order 6-12-2020Document3 pagesBoston Mayor Executive Order 6-12-2020iggybauNo ratings yet

- AAFP Letter To Domestic Policy Council 6-10-2020Document3 pagesAAFP Letter To Domestic Policy Council 6-10-2020iggybauNo ratings yet

- HR 4004 Social Determinants Accelerator ActDocument18 pagesHR 4004 Social Determinants Accelerator ActiggybauNo ratings yet

- Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia DecisionDocument119 pagesBostock v. Clayton County, Georgia DecisionNational Content DeskNo ratings yet

- HR 6437 Coronavirus Immigrant Families Protection AcfDocument16 pagesHR 6437 Coronavirus Immigrant Families Protection AcfiggybauNo ratings yet

- 7th Circuit Affirming Preliminary Injunction Cook County v. WolfDocument82 pages7th Circuit Affirming Preliminary Injunction Cook County v. WolfiggybauNo ratings yet

- S 3721 COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Disparities Task ForceDocument11 pagesS 3721 COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Disparities Task ForceiggybauNo ratings yet

- A Bill: in The House of RepresentativesDocument2 pagesA Bill: in The House of RepresentativesiggybauNo ratings yet

- Milwaukee Board of Supervisors Ordinance 20-174Document9 pagesMilwaukee Board of Supervisors Ordinance 20-174iggybauNo ratings yet

- S 3609 Coronavirus Immigrant Families Protection ActDocument17 pagesS 3609 Coronavirus Immigrant Families Protection ActiggybauNo ratings yet

- HR 6585 Equitable Data Collection COVID-19Document18 pagesHR 6585 Equitable Data Collection COVID-19iggybauNo ratings yet

- HR 6763 COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Disparities Task ForceDocument11 pagesHR 6763 COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Disparities Task ForceiggybauNo ratings yet

- NCAPIP Recommendations For Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Contact Tracing May 2020Document23 pagesNCAPIP Recommendations For Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Contact Tracing May 2020iggybauNo ratings yet

- SF StayHome MultiLang Poster 8.5x11 032620Document1 pageSF StayHome MultiLang Poster 8.5x11 032620iggybauNo ratings yet

- Doe v. Trump 9th Circuit Denial of Stay of Preliminary InjunctionDocument97 pagesDoe v. Trump 9th Circuit Denial of Stay of Preliminary InjunctioniggybauNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 FaceCovering 1080x1080 4 SPDocument1 pageCOVID 19 FaceCovering 1080x1080 4 SPiggybauNo ratings yet

- Physician Association Letter To HHS On Race Ethnicity Language Data and COVID-19Document2 pagesPhysician Association Letter To HHS On Race Ethnicity Language Data and COVID-19iggybauNo ratings yet

- Cook County v. Wolf Denial Motion To Dismiss Equal ProtectionDocument30 pagesCook County v. Wolf Denial Motion To Dismiss Equal ProtectioniggybauNo ratings yet

- Doe v. Trump Preliminary Injunction Against Proclamation Requiring Private Health InsuranceDocument48 pagesDoe v. Trump Preliminary Injunction Against Proclamation Requiring Private Health InsuranceiggybauNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Data For Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders UPDATED 4-21-2020 PDFDocument2 pagesCOVID-19 Data For Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders UPDATED 4-21-2020 PDFiggybauNo ratings yet

- Doe v. Trump Denial of All Writs Injunction Against April 2020 Presidential ProclamationDocument9 pagesDoe v. Trump Denial of All Writs Injunction Against April 2020 Presidential ProclamationiggybauNo ratings yet

- CDC Covid-19 Report FormDocument2 pagesCDC Covid-19 Report FormiggybauNo ratings yet

- Booker-Harris-Warren Letter To HHS Re Racial Disparities in COVID ResponseDocument4 pagesBooker-Harris-Warren Letter To HHS Re Racial Disparities in COVID ResponseStephen LoiaconiNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 Data For Asians Updated 4-21-2020Document2 pagesCovid-19 Data For Asians Updated 4-21-2020iggybauNo ratings yet

- WA v. DHS Order On Motion To CompelDocument21 pagesWA v. DHS Order On Motion To CompeliggybauNo ratings yet

- Tri-Caucus Letter To CDC and HHS On Racial and Ethnic DataDocument3 pagesTri-Caucus Letter To CDC and HHS On Racial and Ethnic DataiggybauNo ratings yet

- ND California Order On Motion To CompelDocument31 pagesND California Order On Motion To CompeliggybauNo ratings yet

- MMMR Covid-19 4-8-2020Document7 pagesMMMR Covid-19 4-8-2020iggybauNo ratings yet

- Pete Buttigieg Douglass PlanDocument18 pagesPete Buttigieg Douglass PlaniggybauNo ratings yet

- Democratic Presidential Candidate Positions On ImmigrationDocument10 pagesDemocratic Presidential Candidate Positions On ImmigrationiggybauNo ratings yet

- Decision-Making Exercises in Business and ScienceDocument5 pagesDecision-Making Exercises in Business and SciencekaosnafeNo ratings yet

- 0923 Part A DCHB Sitapur PDFDocument636 pages0923 Part A DCHB Sitapur PDFGame HackerNo ratings yet

- The Passing of The Public Utility ConceptDocument14 pagesThe Passing of The Public Utility Conceptcagrns100% (2)

- 3atrn Fa4Tt/ Health Department: T3T Ong AeiaiamDocument1 page3atrn Fa4Tt/ Health Department: T3T Ong Aeiaiamaman sharmaNo ratings yet

- Cook v. Harding Dismissal OrderDocument24 pagesCook v. Harding Dismissal OrderJane LarringtonNo ratings yet

- Manifest Shipments of Hazardous WasteDocument7 pagesManifest Shipments of Hazardous Wasteவேல் முருகன்No ratings yet

- The Florida Mental Health Act (The Baker Act) 2000 Annual ReportDocument54 pagesThe Florida Mental Health Act (The Baker Act) 2000 Annual ReportaptureincNo ratings yet

- ScrapDocument106 pagesScrapElliot HofmanNo ratings yet

- MIDWIVES FALSE COPY-davao PDFDocument16 pagesMIDWIVES FALSE COPY-davao PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- CREA Stay of Implementation Letter FINAL 12.5.17Document3 pagesCREA Stay of Implementation Letter FINAL 12.5.17Michael_Lee_RobertsNo ratings yet

- Provisions Relating To Hazardous ProcessDocument21 pagesProvisions Relating To Hazardous Processpsugwekar67% (3)

- Basics of Income Tax and Practical AspectsDocument54 pagesBasics of Income Tax and Practical Aspectsmahek jainNo ratings yet

- Application Form Blood Collection Unit Blood StationDocument5 pagesApplication Form Blood Collection Unit Blood StationRhodora BenipayoNo ratings yet

- Draft Participant List Countries OrganizationsDocument107 pagesDraft Participant List Countries Organizationsashakow8849No ratings yet

- Electric Vehicles and Charging Stations Act summaryDocument18 pagesElectric Vehicles and Charging Stations Act summaryLouie SantosNo ratings yet

- The Price of Bliss Affluence Is A Double Edged Sword. On One Side, The Blade Is Dull and Embedded WithDocument2 pagesThe Price of Bliss Affluence Is A Double Edged Sword. On One Side, The Blade Is Dull and Embedded Withapi-296860658No ratings yet

- Swot Analysis Contex Interested Parties Rev.0Document17 pagesSwot Analysis Contex Interested Parties Rev.0mahm.tahaNo ratings yet

- MUMBAI CONFERENCE VENUE AND EXHIBITOR DETAILSDocument74 pagesMUMBAI CONFERENCE VENUE AND EXHIBITOR DETAILSSadik Shaikh0% (1)

- Rules of Procedure AWMUN IIIDocument28 pagesRules of Procedure AWMUN IIIRila Vita SariNo ratings yet

- Haddonfield 0619Document24 pagesHaddonfield 0619elauwitNo ratings yet

- ECAP Exporter GuidelinesDocument5 pagesECAP Exporter Guidelinesmega87_2000100% (1)

- Level of Health Care Responsiveness at RSND Semarang Inpatient InstallationDocument9 pagesLevel of Health Care Responsiveness at RSND Semarang Inpatient Installationfenita sariNo ratings yet

- 06 WW 17 Feb 2011Document12 pages06 WW 17 Feb 2011Workers.orgNo ratings yet