Professional Documents

Culture Documents

"Energy Revolution Offers Return of 20th Century U.S. Strategic Weapon: Spare Production Capacity," by William Murray

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

"Energy Revolution Offers Return of 20th Century U.S. Strategic Weapon: Spare Production Capacity," by William Murray

Copyright:

Available Formats

Energy Revolution

Offers Return of

20

th

Century U.S.

Strategic Weapon:

Spare Production

Capacity

By

William Murray

2014

O

C

C

A

S

I

O

N

A

L

P

A

P

E

R

4

9

International Research Center

for Energy and Economic

Development

Occasional Papers:

Number Forty-Nine

ENERGY REVOLUTION OFFERS RETURN OF

20

TH

CENTURY U.S. STRATEGIC WEAPON:

SPARE PRODUCTION CAPACITY

by

William Murray

ISBN 0-918714-75-3

Copyright 2014 by the International Research Center for

Energy and Economic Development

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted,

except for brief excerpts in reviews, without written permission

from the publisher.

Cost of publication: U.S. $10.00

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH CENTER FOR ENERGY

AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT (ICEED)

850 Willowbrook Road

Boulder, Colorado 80302 U.S.A.

Telephone: (303) 442-4014

Fax: (303) 442-5042

Email: iceed@colorado.edu

Website: http://www.iceed.org

Energy Revolution Offers Return of

20th Century U.S. Strategic Weapon:

Spare Production Capacity

William Murray*

I ntroduction

The era of U.S. energy abundance has arrived with such speed

and force that we can all be excused for feeling somewhat

disoriented. Even as the economic benefits to the United States

quickly become apparent, the strategic value created by the tens

of billions of barrels discovered through the use of hydraulic

fracturing and horizontal drilling technology is just beginning to

be tested. U.S. President Barack Obamas decision on March 12,

2014, to sell 5 million barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum

Reserve (SPR) was partially a political signal to Russia in

response to its military move into the Crimean Peninsula. Such a

responsea non-supply disruption-related release of sour crude

barrels that compete directly with Russias Urals benchmark

would have been unimaginable less than a decade ago, when the

crude imports made up roughly 60 percent of total U.S.

consumption and the SPRs supplies covered only 69 days of

imports.

But what a difference several years make. The decades-worth

of additional domestic oil and gas now accessible in shale and

other geologic strata has the U.S. Energy Information Admin-

istration (EIA) estimating that the United States will surpass

Russia in 2015 to be the worlds largest oil producer. The EIA

reports the United States has already surpassed Saudi Arabia as

the world largest producer of total hydrocarbons. While it is an

open debate to what degree SPR oil can be used to greatly influ-

ence U.S. foreign policy, the most recent use of the SPR begs the

question. Are there other unforeseen strategic weapons that are

2

now worth considering related to oil supplies that could become

available in the medium- to long-term future? The short answer

is yes. The newly accessible tight oil has given the United States

a chance to recreate one of the greatest strategic weapons of the

20th century: spare oil production capacity.

Spare oil production capacityalso known as swing

capacityis the Excalibur sword of economic and diplomatic

weaponry, but before going into detail, it is worth reviewing a bit

of economic history. From the 1930s until the early 1970s, the

United States was able to lead its allies to victory in the Second

World War and fight the first half of the Cold War thanks to ample

supplies of crude oil. In a long-forgotten development, the state of

Texas in the mid-1930s stabilized volatile oil prices by regulating

private production within its borders, periodically releasing or

constraining millions of barrels of production at a moments notice.

This capacity gave the U.S. effective control over the global price

of oil as Texas regulators, with full authority delegated by

Congress, used proration to restrict output when prices were soft

and order more pumping when prices started to spike, creating a

strategic tool of immense influence. The existence of spare

capacity was used as an instrument of statecraft to build the free-

trade and military alliances in the 1950s and 1960s that became

the foundation of U.S.-led containment policy against Soviet and

Chinese communism.

The Geopolitical Value of Swing Capacity

The central question to be answered by this paper is whether

the United States can recreate spare crude oil production capacity

given current technology and whether the strategic and

geopolitical benefits accrued to the nation by such a tool are

justified. I argue that the United States can and should recreate

spare capacityvia Americas vastly underutilized federally-

owned offshore resourcesand in order to support my argument, I

will explain the theoretical basis by which the United States can

3

create spare capacity after an absence of nearly a half century.

This paper will explore the uses of spare production capacity as a

tool of statecraft using historical examples, including two U.S.

actions restricting oil supplies to compel political allies to end

their military operations and Saudi Arabias use of spare capacity

to equalize its strategic relationship with the United States.

Finally, this paper will explain how the redevelopment and

management of new spare capacity by the federal government

can be sustained both technically and politically.

Oil has been a central factor in a series of conflicts from the

beginning of the 20th century as the world economy industrial-

ized and gasoline and diesel-powered tanks and airplanes began

to dominate European battlefields during the First World War.

One reason the Allies won the Second World War was the ability

by the United States to expand oil production to almost any de-

sired level, while historians point to oil shortages as a major rea-

son for both Germany and Japans failure to permanently secure

their early military gains.

1

Oil was one of the primary causes of

the conflict between the United States and the Empire of Japan

as the Roosevelt administration banned oil exports to Japan in an

effort to discourage Japanese militarism. During the Six-Day

War of 1967 between Israel and Arab nations, the reserve petro-

leum capacity of the U.S. prevented Arab states from using the

threat of an oil embargo to apply political pressure on Western

Europe.

2

Without such a reserve, the United States could have

forfeited many of its foreign policy objectives at critical junc-

tures during the Cold War to whichever governments controlled

allied oil supply. And, in an example of strategic compellence

underappreciated by energy and geopolitical analysts today, dur-

ing the 1956 Suez crisis the United States threatened to withhold

emergency oil supplies from Britain and France until they re-

moved their occupying troops from the Suez Canal zone.

3

A combination of strong U.S. oil demand growth and a de-

cline in oil discoveries in the 1960s led to the loss of Americas

position as the worlds swing petroleum producer. This disap-

pearance in spare capacity surprised U.S. policy makers, causing

4

the United States to enter a decade of failed attempts to protect

the national economy from high and volatile oil prices through

protectionist measures. Spare production capacity was retained

in Saudi Arabia where it has been zealously guarded ever since.

The Saudi Kingdom used the capacity to fill-in missing supplies

disrupted during the 19901991 Gulf War and the 2003 invasion

of Iraq. More recently, Saudi capacity was used for the output

shortfall caused by the 2011 Libyan civil war and U.S.-led sanc-

tions regime against Irans oil industry. Spare capacity gives the

market stability, since traders can count on additional supplies

being available in times of emergency. In return for periodically

using this spare capacity, Saudi Arabia has maintained its strate-

gic relationship with the United States, even in the face of major

policy and political disagreements. On one occasion, its exist-

ence may have created deterrence against a U.S. military attack

on Saudi oil installations.

4

The Role of Compellence and Deterrence in Energy and

National Security

U.S. spare oil capacity can become a tool of statecraft if the

United States has the will to make it so. The use of compellence

is often linked to deterrence theory and nuclear weapons doctrine.

Nuclear weapons theorists such as Thomas Schelling have de-

fined compellence as using the threat of punishment to get a na-

tion to do something and, as a result, change the status quo.

5

In

this way, compellence is the reverse side of deterrence, which

signals to opponents that actions to change the status quo will

backfire. Second-strike nuclear capability is the most popular

example of nuclear deterrence, although many types of deter-

rence below the nuclear threshold exist. Compellence is consid-

ered harder to maintain than deterrence and must be

accompanied with credibility, capacity, and rationality. Compel-

lence usually involves initiating an action on the part of a state to

change an opposing states behavior and can be done through a

5

variety of meansharassment, blockade, travel bans, electronic

disturbance, the use of violent air power, covert activity, and

prisoner-taking to name a few.

6

All of these examples, however, are a type of hostile pres-

sure that can provoke a military response. A less common com-

pellence method involves non-hostile pressures. Schelling uses

the example of the French Armys occupation of a province in

northern Italy in June 1945, just after the end of the Second

World War, with the intention of annexing the area as a minor

frontier adjustment.

7

Despite the action being contrary to Allied

plans and U.S. policy, the French announced that any effort by

allies to dislodge them would be treated as a hostile act. After

arguments with the de Gaulle government went nowhere, Presi-

dent Harry S. Truman informed the French that no more supplies

would be issued to the French army until it had withdrawn to

pre-existing national boundaries.

8

Because the French were en-

tirely dependent on American logistics and supply, this non-

hostile pressure, which did not reach the threshold of provoking

a militant response, was viewed as an unusually safe coercive act,

causing French forces to withdraw quickly. As we will see in

more detail later in this paper, U.S. non-hostile political pres-

sure in the form of a refusal to use spare oil production, initially

promised for use by European allies, will be used against the

French and British militaries during the 1956 Suez Crisis.

In addition to the strategic value of spare capacity to coerce

opponents, its loss over the past 40 years has led to an addiction

to imported oil that has taken a toll on U.S. finances, politics,

and its strategic doctrine. The point has been made many times

that dependence on crude oil imports has become one of the

most serious strategic challenges faced by the United States go-

ing forward. Between 1965 and 2005, the amount of oil import-

ing by the United States increased from 10 percent of its daily

consumption to nearly 60 percent, accounting for trillions of dol-

lars of lost wealth and an enlarged trade deficit. Over the decades,

this dependency transformed the United States from a creditor to

a debtor nation, weakened its currency to a point where its re-

6

serve currency status was questioned, and created a strategic

doctrine leading to limited wars of occupation in oil-exporting

regions, costing both blood and treasure to American society.

The tight oil revolution, combined with improved fuel

efficiency standards, has cut the percentage of imports for daily

consumption in half since 2005, and additional tight oil supply

growth is expected in the next five to seven years. The creation

of a spare capacity would, over time, change the U.S. strategic

relationship with oil exporters even more than the changes

currently under way. The United States, as a result of its military

and political primacy developed during the Cold War, has taken

responsibility as prime defender of the global commons. As a

result, the U.S. military has become the global sheriff in

charge of security of supply for Middle East oil resources

shipped to its European and Asian allies. This Cold War-era

responsibility has not been re-adjusted in the past two decades,

allowing strategic competitors like China, India, and Iran to

benefit from essentially free economic security.

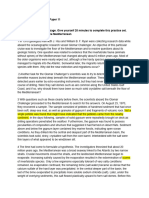

New Hydrocarbon Supply

Up until 20082009, the conventional wisdom held that U.S.

crude production was in inexorable decline. Production of

conventional crude oil peaked in the United States in 1970 at

roughly 9.6 million barrels a day (b/d) and fell to less than 5

million b/d in 2008, the lowest level since the 1940s (see figure

1).

9

But the twin developments of hydraulic fracturing and

horizontal drilling have combined to dramatically increase the

amount of accessible hydrocarbon reserves. By drilling

horizontally, oil explorers can access far greater amounts of oil

or natural gas-bearing formations from a single drilling pad

compared to a vertical well, while hydraulic fracturing uses a

slurry of high-pressure water, silica sand particles, and chemical

additives to create large rock fractures from which hydrocarbons

can drain into the well pipe.

10

7

Figure 1

U.S. FIELD PRODUCTION OF CRUDE OIL, 19202013

(in thousands of barrels per day)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. Field Production of

Crude Oil, available at http://www.eia.gov.

This allows large amounts of tight oil to escape from the rock

that otherwise would have been trapped and irretrievable.

Spurred by oil prices over $100 a barrel, over the past five years

the United States has reversed the long-term domestic production

decline and, in March 2014, produced 8.2 million barrels of

crude a day, the most since May 1988.

11

When adding the addi-

tional production of natural gas liquids, which can also be re-

fined into motor fuels, the United States produced more than

11.5 million b/d of liquid hydrocarbons at the end of 2013.

12

These developments caused the federal governments EIA to es-

timate that tight oil will make up half of the 9.6 million barrels a

day b/d of crude to be produced in the United States in 2020.

13

Roughly 2 million b/d of additional crude has been produced in

the United States in the last two years, and some experts believe

another 2.5 million b/d or more will be added by 2020.

14

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

8

Along with hydraulic fracturing success, advances in computer

power have allowed geologists to increase the rate of discovery

of conventional hydrocarbons. Four decades ago, the discovery

rate per conventional exploratory well drilled was between 20 to

30 percent. Now, explorers are able to drill at 70 to 80 percent

discovery rate, which lowers the risk to investors and increases

the amount of capital available for exploration companies. As a

direct consequence of these technical advances, a study for the

National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners

(NARUC) published in 2010 found the resulting increase in

estimated oil and gas resources from 1970 to 2009 in the Gulf of

Mexico to be between 4 to 6 times larger than initially thought as

a result of evolutionary technology.

15

The U.S. Department of the

Interior in 2006 estimated a mean of 86 billion barrels of oil and

420 trillion cubic feet of natural gas could be discovered in

offshore Continental Shelf areas of the Atlantic, Pacific, and

Eastern Gulf of Mexico by incorporating advances in petroleum

exploration and development technologies.

16

This is roughly four

times the amount of proved reserves currently believed to be

available in the entire United States, but for several decades,

presidential and congressional moratoria had blocked

development of the Atlantic, Pacific, Alaska, and Eastern Gulf of

Mexico. Record high oil prices in July 2008 caused President

George W. Bush to end a presidential moratorium on off-shore

drilling in those areas, followed by a lapse in a congressional

moratorium in September 2008.

A conservative estimate using a NARUC methodology that

accounts for unexpected technological advances would put addi-

tional off-shore production beyond the three-mile limit of 34

million barrels a day over a period of more than a decade, which

when added to the expected expansion of on-shore production

would combine to over 7 million barrels a day of additional U.S.

production. This could give the United States over 15 million

barrels a day of oil production, nearly double what is currently

being produced and well in excess of the record for total liquid

hydrocarbons of 10.975 million barrels a day set in 1973.

17

9

U.S. Use of Oil as Compellence during 1956 Suez Crisis

The true geopolitical potential of spare capacity can be seen

most clearly through the Eisenhower administrations dealings

with both political allies and adversaries during the 1956 Suez

Crisis. The trio of Britain, France, and Israel took military action

against the Egyptian government of Gamal Abdel Nasser in

October 1956 to wrestle back control of the Suez Canal zone

from Egyptian troops who had taken over the corridor in late July.

The Suez was a crucial passageway for Middle Eastern energy

supplies to Europe, and both the United Kingdom and France

had shared ownership and control of the Suez Canal Company

concession for almost 100 years.

18

The fading colonial powers

were interested in regaining control of the canal, but there was

no consensus with Europes newly hegemonic superpower ally,

the United States over how to deal with Nasser.

19

In response to

the July crisis, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized

the creation of a Middle East Emergency Committee, which was

charged with organizing oil supplyderived mainly from U.S.

spare capacityfor Western Europe if the canal was blocked by

Nassers forces.

20

President Eisenhower in particular was adamantly opposed to

military action against Egypt, based on fears of setting off a

wider international crisis involving the Soviet Union. But the

British and French, through a separate, secret track, coordinated

the re-occupation of Suez with help from Israel. On October 29th,

Israel launched an attack into the Sinai, and in early November,

British and French paratroopers arrived in the Canal zone.

21

This

gap of several days between deployments allowed the Egyptian

government to damage the canal, scuttling dozens of ships to

block the waterway and choke off the supply of oil, the security

of which had been the immediate justification of the Europeans

attack.

22

In one of the worst geopolitical calculations of the era,

the British assumed that the United States would step into any oil

shortage with U.S. supplies, but Eisenhower was livid, both for

the secrecy and because the Europeans had failed to account for

10

U.S. elections scheduled for November 6 that had Eisenhower

running for re-election on the top of the ballot. The British

failure to understand U.S. interests also had to do with the

diminishing vision of the British Empire and the expanded vision

and responsibilities of the United States. At the same time as the

Suez Crisis, Soviet troops were entering Budapest to crush the

Hungarian rebellion. To have Western colonial powers invading

a former colony at the same time as the Hungarian uprising

undermined U.S. efforts to unite global opposition against Soviet

aggression in Eastern Europe.

The secret military move by Britain and France was unforgiv-

able in Eisenhowers eyes, and it motivated him to refuse to

permit any of the emergency oil supply arrangement to be put

into action. Instead of providing supplies to U.S. allies, Eisen-

hower would impose oil sanctions to punish and pressure his

allies in Western Europe until they removed their troops from the

Suez Canal zone.

23

The administration thus refused to activate

the Emergency Committee, which had the authority to order new

production from U.S. spare capacity, and without this American

aid, the combination of a blocked Suez Canal and a Saudi em-

bargo would cause all of Western Europe to fall short of oil as

winter approached. With the U.S. announcement of sanctions,

the die was cast. Harold Macmillan, the British Chancellor of the

Exchequer and future British Prime Minister, threw up his arms

into the air when he heard of the move, exclaiming Oil sanc-

tions? That finishes it.

24

French and British troops were out of

the Canal zone by the end of November, only after which did

Eisenhower authorize the activation of the Middle East Emer-

gency Committee.

25

While this episode has fallen down the list of significant

political confrontations during the Cold War, U.S. behavior

regarding its spare oil capacity is instructive. Eisenhower

understood the power of oil capacity as a political tool. Being

able to compel an adversaryor in his view a misbehaving set

of alliesso quickly and in a non-military manner is rare, and

the fact that such episodes have so infrequently occurred in

11

history speaks to its punitive value. Once used as a tool, nations

on the receiving of oil embargos and sanctions rarely forget. In

Britain, the Suez Crisis is seen as one of the defining geopolitical

events of the Cold War, symbolizing a final transfer of

superpower status from Britain to the United States. Prime

Minister Anthony Eden resigned as a result of the failed re-

occupation of the Suez, while the French government within the

next year signed the Treaty of Rome, which laid the foundations

for the European Union by creating the Common Market.

European consolidation was likely sped up by the U.S. action.

German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer told French Premier Guy

Mollet in a Paris meeting in early November 1956 just as the

United States began its Suez response that because individual

European states could never again be leading global powers on

par with the United States and the Soviet Union, there remains

to them only one way of playing a decisive role in the world; that

is to unite to make Europe. . . . Europe will be your revenge.

26

Saudi-U.S. Relations, Deterrence, and Spare Capacity

We have seen strong evidence of the geopolitical power of

spare capacity over the past 40 years concerning U.S.-Saudi

relations. Most observers identify the February 14, 1945 meeting

between President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and King

Abdulaziz al-Saud aboard the U.S.S. Quincy in the Red Sea as

the starting point of a deep U.S.-Saudi political relationship. In

return for U.S. military protection of Saudi Arabias oil industry,

the Saudis agreed to meet global oil market demand and the

needs of U.S. allies. But the Saudi embargo of the United States

and Europe, in response to the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, created an

oil shock that brought the alliance into question. The embargo

produced large-scale inflation in the United States, new concerns

about the security of foreign investment in oil-producing countries,

and open speculation about the feasibility of militarily seizing oil

fields in Saudi Arabia or other countries.

27

Both the Nixon and

12

Ford administrations felt such actions were too high a price to

pay, according to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger at the

time.

28

If you bring about an overthrow of the existing system

in Saudi Arabia and a Qaddafi takes over, . . . youre going to

open up political trends that could defeat your economic

objectives.

29

As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, Saudi Arabia

has had the only meaningful spare capacity in the world since

the 1970s and its importance to the stability of the oil mar-

ketsand equally on the stability of the world economyhas

allowed it to maintain a close relationship with the United

States. The alliance has survived both dramatic differences in

each societys views on political liberty and womens rights

and the consequences of Salafist terrorism practiced by al -

Qaeda and its late Saudi-born founder, Osama bin Laden.

Considering the interventionist policies of a number of U.S.

administrations in the past 20 years in Iraq and elsewhere, it is

likely the U.S.-Saudi relationship has operated on an equal

footing only because of the deterrent effect of Saudi Arabias

massive oil reserves.

While it has been a rule of thumb that spare capacity must

make up about 5 percent of the total oil demand in the world to

be effective, the average over the past decade (20042013) for

the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has

been less than that, according to the EIA, with Saudi Arabia

holding the vast majority. This lowers the bar for the United

States creating a meaningful capacity because, even without

additional U.S. and other production over the next several

decades, Saudi Arabias great strategic asset may be on the

wane. Domestic Saudi electricity demandwhich is currently

produced by burning oil, not natural gascontinues to grow by

10 percent a year and threatens to eat away much of countrys

current spare capacity by 2030.

30

The relative narrowing of

Saudi spare capacity is considered one of the key reasons for

currently high oil prices. While total OPEC spare capacity in

2014 is between 2 to 4 million barrels, analysts such as Londons

13

Chatham House estimates Saudi Arabia will be a net importer of

petroleum as early as 2038,

31

while other estimates imply that

spare capacity may end in the Kingdom as early as 2030 (see

figure 2).

32

The consequences of this dwindling spare capacity

is that high oil prices and high price volatility seen during the

past five to seven years could return rapidly, fueling inflation,

promoting a rise in interest rates, and hampering economic

growth over the long term.

33

If the timing of the elimination of

Saudi spare capacity is accurate, this situation also gives the

United States a two-decade window of opportunity to move

away from its petroleum-based transportation while at the same

time ramping up extra production in order to potentially replace

Saudi Arabias position as producer of last resort.

Figure 2

OPEC SURPLUS CRUDE OIL

PRODUCTION CAPACITY, 20032015

(in million barrels per day)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Short-Term Energy

Outlook (Washington, D.C.: March 2014), available at http://www.eia.gov.

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015

Projected

14

A Change in Demand

New technologies and techniques to increase domestic produc-

tion highlighted above are changing the nature of energy supplies

in the United States today, but there is no way the country can cre-

ate spare crude oil capacity unless it undergoes a radical shift in

the amount of oil used by its thirsty transportation sector. The

United States is the number one user of petroleum in the world

each day, burning 18.9 million b/d in 2013. While the amount of

oil imported has fallen by almost 4 million barrels since 2007, U.S.

imports are still about 7 million b/d.

34

The only way to create

enough spare production capacitythe 2 or more million b/d need

to meaningfully influence global marketsis to dramatically shift

the use of oil in the U.S. transportation system, which currently

consumes about 13.5 million b/d of crude.

35

The United States is

estimated to have used 8.5 percent less oil in 2013 than it did in

2007, largely due to changes in transportation usage, with an addi-

tional 6 percent less by 2025 thanks to new fuel economy stand-

ards passed during the Bush administration and enhanced at the

start of the Obama administration. The new rules will increase

light duty-vehicle fuel efficiency by almost 50 percent, equaling a

savings of about 800,000 b/d.

36

It is not within the purview of this article to detail the dramatic

advances in automotive batteries, hybrid-automobile technology,

compressed and liquefied natural gas-driven vehicles, and full-

electric vehicles made in the past five years. That said, the current

trends show the potential to impact U.S. oil demand in ways simi-

lar to hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drillings impact on re-

cent U.S. oil supply growth. Rigorous studies show that the

continued gap between global oil prices and the price of U.S.-

based natural gas and electricity could, over time, displace internal

combustion-driven transportation vehicles with non-oil-based ve-

hicle fleets. Such a movement toward electricity-driven light-duty

and natural gas-driven vehicle fleets over the next two decades

could dramatically cut the amount of oil being used by the U.S.

transportation systemby as much as 6.5 million b/d by the

15

2040s.

37

The time it takes for disruptive transportation technology

to become standard is generally measured in many decades. The

adoption of combustion-engine automobiles in the United States

took 25 years to take hold from its invention around 1900, and the

full expansion of the U.S. Interstate Highway System took an ad-

ditional 50 years to fully implement. A similar transition to a non-

oil-powered fleet will take decades but will be justifiable if, as a

consequence, the country could de-link its economy from petrole-

um use while developing a strategic spare production capacity that

could be used to the nations advantage.

Policy Suggestions and Implications

The compellent and deterrent power of spare oil production

capacity has few equals as a tool of statecraft, but even if one

comes to accept its strategic value, a second large hurdle to im-

plementation immediately comes into view: politics.

How would the United States manage the asset in a way that

clearly benefits the countrys national and public interest, rather

than a sub-set of oil producers and automobile manufacturers who

already benefit from government incentives and can be defined as

representing special, politically connected interests? Several ex-

amples exist at the federal level involving regulatory institutions

that manage commodities trading and wholesale electricity mar-

kets. These organizations grew out of the Progressive and New

Deal era and continue to operate with little question of their legit-

imacy. Examples include the National Labor Relations Board

(NLRB), the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) that

regulates natural gas pipelines and manages wholesale electricity

prices, the Commodity Future Trading Commission (CFTC), and

the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). These boards all

operate with quasi-judicial powers and do so in a way that depolit-

icizes (to the degree it is possible) the industries they regulate. The

same is true of the hundreds of state-level commissions and boards

operating throughout the country that deal with everything from

16

retail electricity pricing to coastal zone management and cos-

metology licenses. To be sure, there are several dilemmas and

challenges in the creation of a federal spare capacity board, not

the least of which is the simple congressional politics of creating

the grand bargain between those interested in more supply and

those interested in less oil demand. This paper does not deal with

the raw politics of crafting U.S. national energy policy except to

say that issues of legitimacy have become paramount in the eyes

of the U.S. electorate concerning all federal office holders. The

fact that quasi-judicial regulatory bodies have operated throughout

federal and state governments for roughly a century suggests that

the model works for what it is designed to do, which is to regulate

commercial industries. In terms of commodity and specifically oil

production, there have been three government policies used by

U.S. federal and state regulators in the 20th century to support and

control production: oil import quotas, a percentage depletion allow-

ancebasically a tax deduction that acted as an incentive for oil

productionand proration.

38

Of the three, proration has shown it-

self to be the most flexible regulatory tool available to limit oil pro-

duction because it allowed the wells to stay in operation, rather than

shutting down wells in order to lower production. By limiting pro-

duction proportionally to a percentage of the total capacity of each

producer, spare production can be created, and in this way would

likely be the first tool utilized by a federal spare capacity system.

Unfortunately, despite the attraction of a regulatory structure

that aims to de-politicize a major energy security issue like oil de-

pendence and spare capacity, a federal spare capacity

board/commission would probably not have the political legitima-

cy needed on simple constitutional grounds. There are obvious

separation of power issues to deal with, and attempts to influ-

ence the global price of crude oil using federal resources would

have foreign policy implications with every other nation on the

planet. Since the U.S. President is constitutionally obligated to run

foreign policy, any President interested in protecting his or her

constitutional prerogatives would not allow a regulatory body to

directly influence foreign policy. The President already has direct

17

control over the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which has been used

sparingly to fill supply disruptions in other parts of the world.

These releases are usually done in concert with other developed

nations in Europe and Asia that are members of the International

Energy Agency (IEA), although the most recent one in March

2014 was a test release and not coordinated.

So the problem of partisanship and political equities are a real

concern, but this criticism must be measured against spare

capacity as a unique national asset over many election cycles and

political eras. Indeed, it is arguable that swing crude oil capacity is

one of the pre-eminent tools of strategic deterrence and

compellence available short of a nuclear weapon. In terms of

compellence, spare capacity should be viewed as superior to

nuclear weaponry, since there is no de facto taboo against its use,

nor has there been an entire international movement against its

existence in the way the anti-nuclear movement has developed.

This strategic argument has the potential to overwhelm the

ideologies of some partisans, even in the current political

environment. It should also be remembered that spare capacity

was one of the tools of statecraft that knit the free-trade alliances

made with Europe and Asia during the 1950s and 1960s that

served as the foundation for U.S.-led containment policy during

the Cold War. Given these restrictions of constitutional authority

and political legitimacy, it is preferable to pass federal legislation

that allows creation of a committee within the National Security

Council (NSC) bringing together principals from the Departments

of the Interior, Energy, Treasury, Defense, and State while taking

direction from the U.S. President and the National Security

Advisor on how to manage spare capacity. It also makes sense to

focus the actual physical areas of spare capacity on solely

federally-owned offshore areas that have not yet been opened up

to development. The length of both the Presidential and

Congressional moratoria on Outer Continental Shelf (OCS)

exploration that expired in 2008 has allowed for huge swaths of

the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic Ocean to become available even

though the areas are largely unexplored. Taking into account

18

estimates by the 2006 Department of the Interior survey, total

undiscovered reserves in these areas may be in excess of 80 billion

barrels thanks to technological developments involving computer

technology and robotics. It is possible to foresee 34 million

barrels a day of production being available on the OCS that could

become part of a spare oil capacity regime for a period of several

decades. The announcement by the Department of the Interior in

February 2014 of an environmental review validating plans to

expand the acquisition of seismic data off the central and southern

portions of the U.S. Atlantic Coast could be the first baby step

toward future production.

39

Any law passed by Congress creating spare capacity would

focus solely on the unexplored sections of federal off-shore and

exclude all onshore areas, both privately and publically held. The

United States could also enhance its energy security relationship

with the bordering nations of Canada and Mexico, which already

send roughly 1 million and 500,000 barrels a day of oil, respec-

tively, and have a special trading relationship with the United

States through the North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA). This relationship could involve strengthening current

special trading rights and monetary compensation in return for

having some Canadian and Mexican capacity taken off-line at

times of the U.S.s choosing. This type of special relationship be-

tween the United States and its closest neighbors concerning ener-

gy security is not unprecedented. The Eisenhower administration

exempted overland imports from its Mandatory Quota Program

created in 1959, allowing Canadian and Mexico imports special

access to U.S. markets.

40

Building and holding spare capacity is extraordinarily expen-

sive. The most recent large field constructed in Saudi Arabia, the

900,000 barrel-a-day Manifa field, cost $16 billion to build while

the costs of deep-water offshore construction is considerably high-

er.

41

Given that the OCS areas in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic

are essentially frontier provinces with no production infrastructure,

costs would run into the hundreds of billions. It is therefore worth

remembering that the estimated value of the OCS oil at current

19

pricesif taking the technologically enhanced estimatesis

roughly $8 trillion in crude oil alone. These areas could be open to

private investment and production in the many years before U.S.

oil demand fell to levels that allowed the country to start ordering

a proration regime. It would be possible to motivate investment

through the tax code, creating increased deductions or a low or

zero-tax regime during the first decade or more of production in

return for the understanding that in response to a Presidential order,

production could be prorated to achieve a strategic or foreign poli-

cy goal. The Congress could also include state revenue-sharing

with coastal states that currently are not part of the federal royalty

and bidding schemes but would bear the brunt of any environmen-

tal degradation caused by accidents or spills.

Conclusion

In order to create U.S. spare capacity on the scale of several

millions of barrels a day needed to impact world markets, this

paper has explained the policy decisions needed to increase U.S.

crude production to at least 1415 million barrels a day while

cutting domestic oil demand by 6.5 million barrels to 1212.5

million barrels a day. By expanding U.S. energy production to

include off-shore spare capacity, a radical shift would take place in

the relationship between the United States with oil exporters in the

Middle East, Russia, and elsewhere, especially if the spare

production is built while the U.S. economy transitions away from

an oil-based transportation system.

If this was done, high oil prices would not threaten the U.S.

consumer economy in the same way as it would other oil-

importing economies. The United States could send excess oil on-

to the market at times of global shortage or threaten to ration pro-

duction at times of surplus. In global energy markets, the threat of

decisive action is as potent a tool as the action itself, and this tactic

would accrue political power to the United States if it lowered

energy price volatility for consuming countries in Europe, Asia,

20

and the Americas. Conversely, by rationing off-shore production,

the United States could increase prices in a way that disrupts the

economies of importing countries with whom it disagrees, as hap-

pened with Britain and France during the Suez Crisis. For strategic

competitors such as Russia, Venezuela, and Iran, this new political

weapon would be of serious consequence, with the potential to

undermine their primary earning power as petro-states.

Now is the time to initiate a debate unimaginable only five

years ago, namely, should the United States as a matter of national

security build spare oil production capacity? Perhaps, but only if

the American electorate has confidence that the resource

development is taking place with the explicit goal of first creating

spare capacity used to further the nations strategic interests,

followed closely by maintaining the levels of environmental

stewardship modern society has come to demand. Because the

U.S. government never overtly controlled spare production

capacity and because more than a generation has passed since such

a tool existed, Americans can be excused for doubting elements of

a spare production capacity strategy. But given how dramatically

the energy landscape has shifted in favor of the United States in

the past five years, it makes sense to consider the possibility of

creating a major strategic tool for this country that could last until

the end of the Oil Age.

NOTES

* William Murray is a Washington D.C.-based senior reporter with Energy

Intelligence Group (EIG), publisher of 15 energy-related trade magazines, in-

cluding Oil Daily, Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, and Oil Market Intelligence.

Before joining EIG, Mr. Murray worked for Bloomberg News from 20002008

in Washington D.C. and London covering natural gas, oil product, and crude

markets. The author spent the second-half of 2008 embedded with U.S. and Iraqi

military forces in Iraq, reporting for the Long War Journal website. Mr. Murray

received his undergraduate degree from Whitman College and has graduate

degrees from the Columbia University School of Journalism and Georgetown

Universitys Security Studies Program. The opinions expressed in this paper

are his own and do not reflect the views of EIG or its employees with which the

author is associated.

21

1

Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest For Oil, Money & Power (New

York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), p. 137.

2

Ibid.

3

Ibid., p. 491.

4

Ibid., p. 643.

5

Thomas Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven: Yale University

Press, 2008), chapter 2.

6

Ibid., p. 77.

7

Ibid., p. 69.

8

Ibid.

9

U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. Field Production of Crude

Oil, available at http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET

&s =MCRFPUS2&f=A.

10

Congressional Research Service, Unconventional Gas Shales: Development,

Technology, and Policy Issue, report no. R40894, Washington, D.C., October 30,

2009, p. 22, available at http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40894. pdf.

11

Moming Zhou, U.S. Crude Oil Production Rises to Highest in Almost 26

Years, Business Week, March 19, 2014.

12

Amrita Sen, Virendra Chauhan, and Shweta Upadhyaya, US Oil and

Shale Ouptut Dec 2013, Energy Aspects, February 27, 2014.

13

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), 2014 Early Release

Outlook (Washington, D.C.: EIA, 2013), available at http://www.eia.gov/

forecasts/ aeo/ er/executive_summary.cfm.

14

Royal Bank of Canada Report, Conversation with Brookings Charles

Ebinger, March 21, 2014.

15

National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC),

Analysis of the Social, Economic and Environmental Effects of Maintaining Oil

and Gas Exploration and Production Moratoria on and Beneath Federal Lands

(Washington, D.C.: NARUC, February 15, 2010), pp. 312.

16

U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), Bureau of Ocean Energy Man-

agement, Regulation and Enforcement, Assessment of Undiscovered Technical-

ly Recoverable Oil and Gas Resources of the Nations Outer Continental Shelf

2006 (Washington, D.C.: DOI, February 2006), available at http://www.boem.

gov/uploadedFiles/BOEM/Oil_and_Gas_Energy_Program/Resource_Evaluatio

n/Resource_Assessment/2006NationalAssessmentBrochure%283%29.pdf.

17

U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. Production of Crude Oil

and Petroleum Products, available at http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHan

dler.ashx?n=PET&s=MTTFPUS2&f=A.

18

D. Yergin, op. cit., p. 483. It might be noted that unlike the Panama Canal,

the Suez Canal was considered the sovereign property of Egypt. The Suez Ca-

nal Company (Compagnie de Suez) negotiated a concession in 1854 to build

and operate the canal.

22

19

Ibid.

20

Ibid.

21

Ibid., p. 490.

22

Ibid.

23

Ibid., p. 491.

24

Ibid., p. 49192.

25

Ibid., p. 493.

26

Martin Feldstein, The Failure of the Euro: The Little Currency That

Couldnt, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2012, available at http://www.for

eignaffairs.com/articles/136752/martin-feldstein/the-failure-of-the-euro.

27

D. Yergin, op. cit., p. 625 See Congressional Research Service, Oil

Fields as Military Objectives: A Feasibility Study, Committee Print Prepared

for the House Committee on International Relations Special Subcommittee on

Investigations, Washington, D.C., August 21, 1975.

28

Ibid.

29

Ibid.

30

Paul Gamble and Brad Bourland, Saudi Arabias Coming Oil and Fiscal

Challenge, Jadwa Investment, July 2011.

31

Glada Lanh and Paul Stevens, Burning Oil to Keep Cool: The Hidden

Energy Crisis in Saudi Arabia, Chatham House, December 2011.

32

P. Gamble and B. Bourland, op. cit.

33

Robert McNally and Michael Levi, Foreign Affairs, A Crude Predica-

ment: The Era of Volatile Oil Prices, June 12, 2011.

34

U.S. Energy Information Administration, This Week in Petroleum:

Crude Oil Section, March 14, 2014, available at http://www.eia.gov/oog/info/

twip/ twip_crude.html#production.

35

U.S. Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook 2014

Early Release (Washington, D.C.: EIA, December 16, 2013), available at http://

www.eia.gov/forecasts/aeo/er/early_consumption.cfm.

36

Ibid.

37

Electricity Coalition, Electrification Roadmap: Revolutionizing Transporta-

tion and Achieving Energy Security (Washington, D.C.: Electricity Coalition,

November 2009), p. 11.

38

Richard Vietor, Energy Policy in America since 1945 (Cambridge, United

Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1984), p. 224.

39

U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), Atlantic Geologi-

cal and Geophysical (G&G) Activities Programmatic Environmental Impact

Statement (PEIS), available at http://www.boem.gov/Atlantic-G-G-PEIS/.

40

R. Vietor, op. cit., p. 128.

41

R. McNally and M. Levi, op. cit.

You might also like

- The Journal of Energy and DevelopmentDocument21 pagesThe Journal of Energy and DevelopmentThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- On The Effects of Access To Electricity On Health Capital Accumulation in Sub-Saharan Africa by Idrissa Ouedraogo, Alex Nester Jiya, and Issa DiandaDocument26 pagesOn The Effects of Access To Electricity On Health Capital Accumulation in Sub-Saharan Africa by Idrissa Ouedraogo, Alex Nester Jiya, and Issa DiandaThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Journal of Energy and DevelopmentDocument29 pagesThe Journal of Energy and DevelopmentThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- Journal of Energy and Development, Vol. 48. No. 2Document161 pagesJournal of Energy and Development, Vol. 48. No. 2The International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "Causes of Disagreement in Electricity Generation Among Stakeholders in Sub-Saharan Africa" by Mekobe AjebeDocument20 pages"Causes of Disagreement in Electricity Generation Among Stakeholders in Sub-Saharan Africa" by Mekobe AjebeThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "Economic Analysis of A Grid-Connected PV Plant: A Case Study in French Guiana" by Wilna Lesperance, Jules Sadefo Kamdem, and Laurent LinguetDocument31 pages"Economic Analysis of A Grid-Connected PV Plant: A Case Study in French Guiana" by Wilna Lesperance, Jules Sadefo Kamdem, and Laurent LinguetThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "The Effects of Natural Resource Extraction and Renewable Energy Consumption On Carbon Dioxide Emissions in Sub-Saharan Africa" by Paul Adjei KwakwaDocument29 pages"The Effects of Natural Resource Extraction and Renewable Energy Consumption On Carbon Dioxide Emissions in Sub-Saharan Africa" by Paul Adjei KwakwaThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Journal of Energy and DevelopmentDocument33 pagesThe Journal of Energy and DevelopmentThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Journal of Energy and DevelopmentDocument23 pagesThe Journal of Energy and DevelopmentThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- Journal of Energy and Development, Volume 48, Number 1Document158 pagesJournal of Energy and Development, Volume 48, Number 1The International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Journal of Energy and Development: "Crude Oil Market Risk Evaluations Under The Presence of The COVID-19 Pandemic,"Document22 pagesThe Journal of Energy and Development: "Crude Oil Market Risk Evaluations Under The Presence of The COVID-19 Pandemic,"The International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "Impact of Oil Revenue On Unemployment in Nigeria: Evidence From ARDL and Quantile Regression Methods" by Isiaka Akande Raifu and Alarudeen AminuDocument34 pages"Impact of Oil Revenue On Unemployment in Nigeria: Evidence From ARDL and Quantile Regression Methods" by Isiaka Akande Raifu and Alarudeen AminuThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Journal of Energy and DevelopmentDocument30 pagesThe Journal of Energy and DevelopmentThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "Environmental Good Valuation: The Case of Drinking Water in Tunisia" by Ali Bouchrika, Fakhri Issaoui, and Slah SlimaniDocument18 pages"Environmental Good Valuation: The Case of Drinking Water in Tunisia" by Ali Bouchrika, Fakhri Issaoui, and Slah SlimaniThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Journal of Energy and DevelopmentDocument44 pagesThe Journal of Energy and DevelopmentThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "Foreign Direct Investments in Low - and Middle-Income Countries in Africa: Poverty Escalation or Reduction?" by Atif AwadDocument29 pages"Foreign Direct Investments in Low - and Middle-Income Countries in Africa: Poverty Escalation or Reduction?" by Atif AwadThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Journal of Energy and Development: "Energy Consumption Reduction of A High-Tech Fab in Taiwan,"Document25 pagesThe Journal of Energy and Development: "Energy Consumption Reduction of A High-Tech Fab in Taiwan,"The International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "India's Emergence As A Petroleum Products Exporter" by Muhammad AzharDocument27 pages"India's Emergence As A Petroleum Products Exporter" by Muhammad AzharThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "Does Electricity Use Granger-Cause Mortality?" by Olatunji Abdul ShobandeDocument28 pages"Does Electricity Use Granger-Cause Mortality?" by Olatunji Abdul ShobandeThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "Optimal Investment Scenarios For The Power Generation Mix Development of Iraq," by Hashim Mohammed Al-Musawi and Arash FarnooshDocument17 pages"Optimal Investment Scenarios For The Power Generation Mix Development of Iraq," by Hashim Mohammed Al-Musawi and Arash FarnooshThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "Impact of Rural Electrification On Ugandan Women's Empowerment: Evidence From Micro-Data," by Niyonshuti Emmanuel and Kwitonda JaphetDocument19 pages"Impact of Rural Electrification On Ugandan Women's Empowerment: Evidence From Micro-Data," by Niyonshuti Emmanuel and Kwitonda JaphetThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)100% (1)

- "Energy Consumption-Economic Growth Nexus in Sub-Saharan Countries: What Can We Learn From A Meta-Analysis (1996-2016) ?" by Alexis VessatDocument25 pages"Energy Consumption-Economic Growth Nexus in Sub-Saharan Countries: What Can We Learn From A Meta-Analysis (1996-2016) ?" by Alexis VessatThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Journal of Energy and DevelopmentDocument23 pagesThe Journal of Energy and DevelopmentThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "Challenges of Economic Growth and Development in Oil-Rich Countries: A Heterogeneous Panel Data Study," by Alireza MotameniDocument66 pages"Challenges of Economic Growth and Development in Oil-Rich Countries: A Heterogeneous Panel Data Study," by Alireza MotameniThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)100% (1)

- "Sustainable Energy Security For Economic Development: Trends and Challenges For Bangladesh" by Shahi Md. Tanvir AlamDocument20 pages"Sustainable Energy Security For Economic Development: Trends and Challenges For Bangladesh" by Shahi Md. Tanvir AlamThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Journal of Energy and DevelopmentDocument26 pagesThe Journal of Energy and DevelopmentThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- "CO2 Emissions and Growth: Exploring The Nexus Between Renewable Energies, Economic Activity, and Technology," by Ali Maâlej and Alexandre CabagnolsDocument24 pages"CO2 Emissions and Growth: Exploring The Nexus Between Renewable Energies, Economic Activity, and Technology," by Ali Maâlej and Alexandre CabagnolsThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)100% (1)

- "Reviewing Fusion Energy To Address Climate Change by 2050" by Elias G. Carayannis, John Draper, and Charles David CrumptonDocument46 pages"Reviewing Fusion Energy To Address Climate Change by 2050" by Elias G. Carayannis, John Draper, and Charles David CrumptonThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- The Co-Evolution of Energy Intensity and Carbon Emissions in Morocco," by Mehdi Jamai Mouhtadi and Jules Sadefo KamdemDocument15 pagesThe Co-Evolution of Energy Intensity and Carbon Emissions in Morocco," by Mehdi Jamai Mouhtadi and Jules Sadefo KamdemThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)100% (1)

- "Evolving U.S., Russian, and Chinese Energy Policies: Implications For GCC Oil," by Øystein NorengDocument33 pages"Evolving U.S., Russian, and Chinese Energy Policies: Implications For GCC Oil," by Øystein NorengThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Riddles of Prehistoric Times PDFDocument304 pagesRiddles of Prehistoric Times PDFLeigh Smith100% (2)

- Acuña 2013 First Record of Three Shark SpeciesDocument6 pagesAcuña 2013 First Record of Three Shark SpeciesHarry JonitzNo ratings yet

- EGI Project Reports 2021Document126 pagesEGI Project Reports 2021dino_birds61130% (1)

- Spykman - Geography and Foreign Policy (I) PDFDocument24 pagesSpykman - Geography and Foreign Policy (I) PDFAdina PinteaNo ratings yet

- Practical Fishkeeping - April 2019 PDFDocument116 pagesPractical Fishkeeping - April 2019 PDFAlexeyDenisov0% (1)

- Exploration Opportunities in The Faroe Islands: January 2005Document18 pagesExploration Opportunities in The Faroe Islands: January 2005Nurul Fatin Izzatie Haji SalmanNo ratings yet

- U-Boat Monthly Report - Jun 1943Document63 pagesU-Boat Monthly Report - Jun 1943CAP History Library100% (1)

- Edgar Cayce - PredictionsDocument9 pagesEdgar Cayce - PredictionsPingus97% (34)

- Jitorres - Victor Cutter, United Fruit Company 1915Document15 pagesJitorres - Victor Cutter, United Fruit Company 1915Sebastián Ríos LozanoNo ratings yet

- HAKES OF THE WORLD (Family Merlucciidae)Document14 pagesHAKES OF THE WORLD (Family Merlucciidae)dutvaNo ratings yet

- Beginning of Reading PassageDocument13 pagesBeginning of Reading PassageswatiNo ratings yet

- Hurricane Case StudyDocument15 pagesHurricane Case StudyAdarsh PNo ratings yet

- Weber Et Al 2001 PalocDocument13 pagesWeber Et Al 2001 PalocOm BambangNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Carbon Footprint in Different Industrial Sectors, Volume 2Document304 pagesAssessment of Carbon Footprint in Different Industrial Sectors, Volume 2Teresa MataNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of World Regional Geography. by Hobbs, Joseph J.Document609 pagesFundamentals of World Regional Geography. by Hobbs, Joseph J.Minh KhôiNo ratings yet

- Early Human Settlement of Northeastern North AmericaDocument61 pagesEarly Human Settlement of Northeastern North AmericaVictor CiocalteaNo ratings yet

- Updated Hurricane StatisticsDocument1 pageUpdated Hurricane StatisticsDrew ShawNo ratings yet

- Imray Atlantic Islands 4ed 2004 Hammick 0852887612Document340 pagesImray Atlantic Islands 4ed 2004 Hammick 0852887612Alfonso Gomez-Jordana MartinNo ratings yet

- KAUKIAINEN - Shrinking The WorldDocument28 pagesKAUKIAINEN - Shrinking The Worldmancic55No ratings yet

- SPE Salary SurveyDocument6 pagesSPE Salary SurveyPham Huy ThangNo ratings yet

- Hurrican Project SolutionDocument5 pagesHurrican Project SolutionKandyNo ratings yet

- Deichmann 1930 PDFDocument234 pagesDeichmann 1930 PDFAnderson GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Minoan Colonies in AmericaDocument8 pagesMinoan Colonies in AmericaGREECEANDWORLD100% (1)

- EuropeDocument21 pagesEuropeNur MohammadNo ratings yet

- The World Factbook: O C e A N S:: Atlantic OceanDocument5 pagesThe World Factbook: O C e A N S:: Atlantic OceanWajahat GhafoorNo ratings yet

- Hurricane Katrina Research PaperDocument4 pagesHurricane Katrina Research PaperSharon Sanxton GossettNo ratings yet

- Lab Report 2Document2 pagesLab Report 2konark100% (1)

- Ocean Currents - Shortcut Method by To Learn Faster - Clear IASDocument15 pagesOcean Currents - Shortcut Method by To Learn Faster - Clear IASgeorgesagunaNo ratings yet

- 1621496007TOEFL Reading Practice Paper 11Document11 pages1621496007TOEFL Reading Practice Paper 11Ojaswa PathakNo ratings yet

- 2007 Schmidt2007 PanamaDocument17 pages2007 Schmidt2007 PanamaEDWIN URREA ZULUAGANo ratings yet