Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Debate On Fiscal Policy in Europe: Beyond The Austerity Myth

Uploaded by

Бежовска Сања0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views6 pagesдфбфбвг

Original Title

eb20_en

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentдфбфбвг

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views6 pagesThe Debate On Fiscal Policy in Europe: Beyond The Austerity Myth

Uploaded by

Бежовска Сањадфбфбвг

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

ECFIN economic briefs are occasional working

papers by the European Commissions Directorate-

General for Economic and Financial Affairs

which provide background to policy discussions.

They can be downloaded from:

ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications

European Union, 2013

Reproduction is authorised

provided the source is acknowledged.

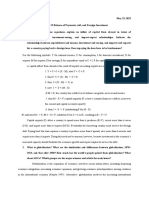

Summary

Several criticisms of the current fiscal

strategy in the EU have recently been

forcefully expressed. In this brief, we

examine these criticisms, and provide

some clarifications and responses. We

recall that large adjustments are needed

in most economies to restore sustaina-

ble fiscal positions, not because of the

arbitrary will of the markets or of EU

institutions. We then examine the de-

bate over the precise speed of fiscal

consolidation, which blends arguments

over the short-run growth effects but

also over the various possible costs and

problems of no-consolidation. In prac-

tice, fiscal policy recommendations un-

der the EU framework have struck a

balance between the conflicting consid-

erations.

Overall, we argue that the current EU

fiscal strategy is essentially in line with

the approach favoured by other interna-

tional organisations. The EU fiscal rec-

ommendations are not an ideological

call for austerity at all costs. In general,

the flexibility embodied in the rules is

being used within a "steady structural"

strategy. Attention is also being paid to

softening the consequences of fiscal

adjustments, and fostering the return to

sustainable growth and jobs, through a

careful design of fiscal consolidation

packages, structural reforms, and a

restoration of functioning financial

channels. Finally, a differentiated fiscal

consolidation is part of the rebalancing

process at work within the euro area,

whereby the efforts of vulnerable euro

area countries should be matched by

rebalancing trends and appropriate poli-

cies in countries that feature large cur-

rent account surpluses.

Issue 20 | March 2013 ISSN: 1831-4473

The debate on fiscal policy in Europe: beyond

the austerity myth

By Marco Buti and Nicolas Carnot

Introduction

The debate on the fiscal strategy

in Europe seems at times like a

war of religions. This is unfortu-

nate because the objective disa-

greements in substance are in our

view less pronounced than is

sometimes depicted.

In this brief we lay out the main

tenets of the EU approach to cur-

rent fiscal adjustments. It is not a

dogmatic call for austerity at all

costs. Rather, it is a delicate bal-

ancing act between implementing

credible adjustments, keeping

flexibility against shocks, and fac-

toring in institutional constraints.

We constantly keep our approach

under review.

We proceed by examining more

closely some of the accusations

levelled against fiscal policy rec-

ommendations adopted by the

Council under the EU framework.

Our claim is not that recommenda-

tions have always been "just

right", nor that they could not be

improved upon in any specific as-

pects. But we would say that more

often than not, these recommen-

dations have been and remain

sensible and in line with those ad-

vocated by other institutional or-

ganisations such as the IMF or the

OECD.

1. Allegation 1: There was irra-

tional panic in the sovereign

bond markets of vulnerable

European countries, and this

led to the imposition of unnec-

essary harsh consolidation.

This criticism is laid out in particu-

lar by de Grauwe and Ji (2013).

There are two aspects: one is

about the functioning of financial

markets and the value of market

signals; the other about the fiscal

policy response.

There is agreement that markets

are prone to excessive swings.

This need not imply, however, that

markets acted purely out of irra-

tional fear in the sovereign bond

crisis.

ECFIN Economic Brief Issue 20 | March 2013

First, some investors did lose money on Greek bonds

after all. Second, although arguably excessive at times,

sovereign spreads were and are at least loosely corre-

lated with the underlying fundamentals. So even

though they may not reflect only fundamentals,

spreads are not unrelated to objective factors either.

It is clear that the announcement of the OMT pro-

gramme by the ECB has had a critical effect on market

expectations. By this move, which aimed at ensuring

effective monetary policy transmission and preventing

redenomination risks, the threat of a self-fulfilling li-

quidity crisis is being assuaged. Effectively, the possi-

bility of ECB interventions in the secondary market

helps coordinate market expectations: investors rightly

believing in the sustainability of a country do not have

to fear a liquidity crisis.

As is clear as well however, the OMT announcement per

se does not address the underlying sustainability con-

cerns. Vulnerable countries have sustainable positions

under the condition that they adjust. The OMT itself is a

programme of sovereign debt purchase under strict and

effective conditionality. Fiscal adjustment and the pos-

sibility to activate the OMT are thus in strong comple-

mentarity. The fact that the reduction in spreads coin-

cided with the announcement of the OMT is no suffi-

cient evidence that the concomitant consolidation ef-

forts were not necessary.

The growing perception that adjustments are underway

likely also contributed to the improvement in markets.

This is disputed, because public debt ratios have re-

cently continued to rise. But debt ratios are a quite

lagged indicator of progress in fiscal sustainability. Pro-

gress has been much more evident when looking at the

reduction in fiscal deficits, especially in cyclically-

adjusted terms, even though the growth picture has

remained weak. On average the euro area structural

balance has been cut from 4% to 1% between

2009-2013, with much stronger adjustments in coun-

tries such as Greece or Portugal. There has also been

visible progress in improving external and relative com-

petitiveness positions.

To summarise on this point: we agree that markets are

liable to multiple equilibria. But we would not infer that

they have just been producing irrational signals in the

sovereign crisis. Further, the effect of the OMT an-

nouncement, while undisputed, cannot be read as evi-

dence that significant fiscal adjustment was unwarrant-

ed. Now, it may be argued that consolidation, while

necessary, was not needed to the extent prescribed.

This leads to the next point.

2. Allegation 2: The adjustment is too front-

loaded.

There is widespread agreement that fiscal consolidation

should be pursued in most European countries. This is

the view of the IMF, the OECD and the Commission.

Large improvements in fiscal positions are needed (and

underway) to stabilise and reduce high levels of debt.

Even vocal critics of the EU often admit that fiscal con-

solidation is unavoidable, in particular in countries

where sustainability is at risk. It is important to under-

line this area of agreement. Once it is admitted that

fiscal adjustment is due, the issue becomes not one of

principle, but one of degree.

Many commentators say the problem is rather that ad-

justment is overly frontloaded, especially for the euro

area periphery (e.g. Wolf, 2013). These criticisms rare-

ly give details on their own prescribed course. Running

fiscal policies requires operational annual budgetary

targets consistent with a credible medium-term plan.

Country-specific features are important as well to con-

sider (Gros, 2013). A sweeping conclusion that fiscal

retrenchment is excessive without specifying a detailed

alternative is in a sense evacuating the hardest issues

faced by policymakers.

The recent international consensus is that fiscal consol-

idation needs to continue at a gradual and sustained

pace, and that fiscal adjustment in most advanced

economies is broadly appropriate (IMF, 2013).

When setting the pace of fiscal adjustment, two consid-

erations are critical from a technical standpoint. One is

the economic outlook, including what we know of the

short-term effects of consolidation (the multiplier). An-

other is the sustainability gap, understood as the scope

of needed adjustment over the medium-run. The EU

framework calls for paying attention to both.

It is agreed that there is no single fiscal multiplier

across fiscal variables, countries and time. In particular,

as compared with usual circumstances, there are rea-

ECFIN Economic Brief Issue 20 | March 2013

sons to expect higher multipliers in an environment of

weak activity, lack of room for a supportive monetary

policy, and tight financing constraints for private

agents.

All else equal, non-linearity in the growth cost of fiscal

adjustment does call for spreading out adjustments

over time. A variant of this argument is to allow se-

quencing of public and private deleveraging for getting

out of a balance-sheet recession. The Japanese fiscal

retrenchment of the late 1990s is frequently invoked as

a case of premature tightening (Koo, 2008).

The policy implications require treading a fine line how-

ever. The above arguments have to be weighed against

several opposite considerations:

First, while consolidation may be now more costly than

in normal times, no or limited consolidation may in

some cases have even worse consequences, notably if

it triggers market expectations of a sovereign default

and a liquidity crisis (Corsetti, 2012). This risk might

have been recently lowered with the ECB announce-

ment of the OMT, but the latter does not remove the

need to demonstrate early commitment to fiscal consol-

idation, as noted above.

The second point is simply basic arithmetic: when the

scope of required adjustment is large on the medium-

term, even a gradual consolidation strategy spreading

out consolidation over several years in broadly equal

instalments will translate in not-insignificant fiscal effort

from the beginning. While measuring fiscal sustainabil-

ity gaps is fraught with difficulties, the indicators com-

piled by the Commission for EU countries, which are

widely acknowledged, suggest that in a number of cas-

es sustainability gaps are at historic highs (European

Commission, 2012a). The IMF considers a structural

adjustment pace of 1% a year as a useful guideline,

with needed differentiation according to the country

situation (IMF, 2012). The SGP requires an annual

structural adjustment of 0,5%, and more in the case of

vulnerable countries. While fully back-loading consoli-

dation to better times might still be theoretically envis-

aged, the risks of time-inconsistency and lack of credi-

bility cannot be neglected. In addition, one cannot be

sure by when and how much the multiplier could fall in

the future (Wolff, 2013).

Finally, the room for trading off public against private

deleveraging depends on the overall external position

of the country. Contrarily to Japan in the 1990s, euro

area countries under distress face a big overall external

challenge that must be confronted by significant ad-

justments of the nation as a whole. This is bound to be

painful, whatever the exact distribution between public

and private deleveraging. Again, this does not fully re-

move the case for sequencing, but it limits the scope

and benefits of such approach.

Policy prescriptions for fiscal policies under the E(M)U

framework have struck a balance between these con-

flicting considerations. It should be recalled that the

fiscal exit strategy originated in the early response to

the crisis in the form of a fiscal stimulus in 2009/2010.

Many initial recommendations under the excessive defi-

cit procedure (EDP) were drafted in this period, where

it was agreed that the initial fiscal relaxation should be

followed by fiscal retrenchment to stabilise and reduce

debts. Recommendations set out at the time, of which a

number remain in place, charted a path of sustained

but spread out adjustment over several years, and with

more effort required when the sustainability challenge

is bigger.

The adjustments underway are a reflection of accumu-

lated imbalances and the massive effects of the crisis.

These are the essential motivations for current consoli-

dation efforts, not the arbitrary will of EU authorities or

financial markets. As developed in the next point, the

Commission has made use of the flexibility embodied in

the EU rule-based framework (Buti and Pench, 2012).

The precise pace of adjustment remains a delicate bal-

ance in each country specific cases, and may always be

discussed. For example, future recommendations could

better factor in the consequences of changes in growth

models (such as rebalancing towards the tradable sec-

tor) in terms of lower tax elasticities.

3. Allegation 3: The Commission follows an

inflexible approach.

This criticism comes at a paradoxical time. The Com-

mission has taken the initiative by proposing to extend

deadlines for correcting the excessive deficit in several

countries. Besides, a key aspect of the flexible ap-

proach we have adopted has recently been to make

more explicit the focus on structural targets, rather

than just the overall deficit of a country. We expect this

to remain important going forward.

ECFIN Economic Brief Issue 20 | March 2013

A key characteristic of recommendations under the SGP

is that the deadline for reducing the nominal deficit be-

low 3% of GDP is conditional on the macroeconomic

forecast at the time of issuing the recommendation.

Missing the nominal targets does not expose the coun-

try concerned to an escalation of the excessive deficit

procedure, including the possibility of financial sanc-

tions, if the structural effort (specified in the recom-

mendation in terms of changes in the cyclically-

adjusted balance net of one-off and temporary

measures) has been delivered. Rather in these cases

the country would receive an extension of the deadline

for correcting its excessive deficit. The absolutely key

point here is that we have not, and will not, pursue

dogmatic targets for the reduction of the headline fiscal

deficit, irrespective of the circumstances a country finds

itself in.

The reliance on structural targets provides both pre-

dictability and flexibility, and hence supports the credi-

bility of the adjustment strategy. The predictability

stems from the fact that countries can embark on a

"steady structural approach". The flexibility lies in al-

lowing the automatic stabilisers to play out around the

(structural) path of adjustment. Unless warranted by an

overwhelming financing constraint, there is no need to

chase nominal targets when growth disappoints. Of

course cyclically-adjusted balances are not without limi-

tations either, based as they are on conventional as-

sumptions about the working of the economy and the

budget. But our surveillance framework is being devel-

oped to take into account these limitations when as-

sessing the effective delivery of the structural fiscal ef-

fort (European Commission, 2012b).

This has been the approach followed in several occa-

sions already, including for the three programme coun-

tries (Greece, Ireland and Portugal) as well as for Spain

last year. Further extensions of deadline may be rec-

ommended in the near future, as the Commission has

already made clear in presenting its winter forecasts.

The simple allegation that the Commission pursues aus-

terity inflexibly does not hold. Nor obviously does the

opposite accusation that the framework is being weak-

ened by downplaying the role of headline balances. The

size of the fiscal adjustment already produced in vul-

nerable countries and elsewhere is testimony against

that.

4. Allegation 4: Fiscal consolidation is not po-

litically or socially sustainable.

There is no denying that the adjustments undergone by

several countries are severe and this may strain social

cohesion. However, there is much to do in order to sof-

ten the consequences of adjustments, and accelerate

the return of a sustainable recovery:

The composition of fiscal adjustment should be

carefully designed. That often means some emphasis

on expenditure restraint, but needs to go beyond that

in order to pick-up growth-friendly measures in an en-

compassing manner. Spreading the costs across the

population and confronting vested interests which often

protect less productive spending help generate a sense

that everyone pays their fair share. Besides, imple-

menting structural fiscal reforms, such as pension re-

forms, improve public sustainability (and medium-term

growth) without weighing on aggregate demand in the

short-run, although not all consolidation can go this

route in practice.

Another aspect is structural reforms promoting

better functioning labour and product markets. In the

present juncture, fiscal consolidation and reform re-

sponsiveness go hand in hand (Buti and Padoan,

2012). Structural reforms can alter not only the effi-

ciency with which economies respond to shocks, but

also the distribution of the effects. For example, flexible

work arrangements and lower nominal rigidities reduce

the impact of downturns on outright layoffs. Reducing

rents in product markets would help ensuring the pass-

through of wage restraint on prices and distributing

purchasing power to households. In other cases (such

as changing employment protection legislation), re-

forms would not help cushioning the impact of negative

shocks, although they may foster a stronger upturn.

These issues are not just a matter of efficiency, but

also of sharing the cost of adjustment in an equitable

manner (Coeur, 2013).

The cost of total deleveraging may also be

made lower by a number of other factors, such as effi-

cient bankruptcy procedures or genuine financial repair

that allows lending to dynamic parts of the economy to

go unhindered. Besides, restoring effective monetary

policy and credit channels throughout the zone is likely

to soften the costs of consolidation. The primary objec-

tive should be to lay the basis for a sustainable recov-

ery.

ECFIN Economic Brief Issue 20 | March 2013

In countries inside our outside the euro area

under a EU-IMF programme, efforts have been taken by

the governments concerned and the troka (Commis-

sion, IMF, ECB) to embed equity considerations in fiscal

adjustment plans. Tax measures have focused on high-

er income brackets, and cuts in government wages or

social benefits have often spared the lowest income

levels. In some of the countries, the internal and exter-

nal imbalances were so large and deep-rooted that rad-

ical choices had to be considered to rebuild their eco-

nomic and policy credibility.

5. Allegation 5: The Commission's approach

is one-sided. It puts all the burden of adjustment

on debtor countries.

Several observers have pointed to the spillover implica-

tions of fiscal policies, and possibly insufficient policy

coordination in the EU (e.g. Holland and Portes, 2012).

We would agree that the symmetry of the adjustment is

a legitimate concern. There are ways to favour a coor-

dinated approach to rebalancing, but the currently

available tools also present limitations.

For vulnerable countries of the euro area that face a

large external sustainability gap, external growth is the

only sustainable way to grow out of their debts. They

must undergo rebalancing but their adjustment should

indeed not be unduly hampered, and ideally should be

fostered by concomitant changes elsewhere.

The improved current balances in the periphery thus

have to be matched by rebalancing trends also in euro

area countries that feature large current account sur-

pluses. Policies and reforms supporting demand in the-

se countries have a role to play. In Germany, the fiscal

stance is now broadly neutral, hence consistent with

the call for a differentiated fiscal stance according to

the budgetary space. Reforms advocated by the Com-

mission and the Council in labour and product markets

or the tax system should contribute to raising domestic

demand. There is also an increasing willingness to allow

wages to reflect the higher productivity in surplus coun-

tries. And since fiscal consolidation cum deflation is

likely to be self-defeating, re-establishing competitive-

ness across the area implies higher than average infla-

tion in stronger countries, provided price stability in the

euro area as a whole is ensured and expectations well

anchored.

The discussion also has implications for the long-run

improvement of EMU architecture. The current situation

appears as a cas d'cole for the potential attraction of a

"fiscal capacity" at the central level, in the form of a

stabilisation instrument, which the Commission has

evoked in its Blueprint on the future of EMU (European

Commission, 2012c). A dedicated stabilisation fund

could improve the conduct of fiscal policies throughout

the cycle by enforcing tighter policies in good times and

providing additional leeway for cushioning downturns.

Such a tool could strengthen the existing automatic

stabilisers while maintaining a credible rule-based

framework. It would be particularly useful in the cur-

rent predicament characterised by large cyclical differ-

entials across the zone as well as a not insignificant

average output gap. However, according to the Com-

mission blueprint such a tool should only be considered

in the longer term in the context of full fiscal and eco-

nomic union.

References

Buti M., P.C. Padoan (2012), From a vicious to a virtu-

ous cycle in the Eurozone the time is ripe, VoxEU, 27

March.

Buti M., L. Pench (2012), Fiscal austerity and policy

credibility, VoxEU, 20 April.

Coeur B. (2013), Adjustment and growth in the euro

area economies, Speech at the Nova school of business

and economics and the Banco de Portugal, February.

Corsetti G. (2012), Has austerity gone too far?, VoxEU,

2 April.

De Grauwe P., Y. Ji (2013), Panic-driven austerity in

the Eurozone and its implications, VoxEU, 21 February.

European Commission (2012a), Fiscal sustainability

report 2012, European Economy, N8, December.

European Commission (2012b), 2012 report on public

finances in EMU, European Economy, N4, July.

European Commission (2012c), A blueprint for a deep

and genuine EMU - Launching a European debate,

Communication from the Commission, COM 2012(777).

ECFIN Economic Brief Issue 20 | March 2013

Gros D. (2013), Learning from small countries? Con-

temporary Nordic Sagas, CEPS Commentaries, Febru-

ary.

Holland D., J. Portes (2012), Self-defeating austerity?,

VoxEU, 1 November.

IMF (2012), Nurturing credibility while managing risks

to growth, Fiscal Monitor Update, July.

IMF (2013), Global Prospects and Policy Challenges,

Note for the Group of Twenty, February.

Koo R. (2008), The holy grail of macroeconomics: Les-

sons from Japan's great recession, Wiley.

Wolf M. (2013), The sad record of fiscal austerity, Fi-

nancial Times, 27 February.

Wolff G. (2013), Austerity needed to start, now we

need a fiscal union, Bruegel blog, 25 February.

You might also like

- Mediocre Growth in The Euro Area: Is Governance Part of The Answer?Document5 pagesMediocre Growth in The Euro Area: Is Governance Part of The Answer?BruegelNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument3 pagesDownloadnickedia17No ratings yet

- Unpleasant Debt Dynamics: Can Fiscal Consolidations Raise Debt Ratios?Document37 pagesUnpleasant Debt Dynamics: Can Fiscal Consolidations Raise Debt Ratios?AdminAliNo ratings yet

- Structural Deficit Limit Improves Fiscal Discipline in Euro AreaDocument9 pagesStructural Deficit Limit Improves Fiscal Discipline in Euro AreaGigelMaracineanuNo ratings yet

- 28 PDFDocument30 pages28 PDFdimikatsouNo ratings yet

- The G20 in The Aftermath of The Crisis: A Euro-Asian ViewDocument7 pagesThe G20 in The Aftermath of The Crisis: A Euro-Asian ViewBruegelNo ratings yet

- Project Objectives and Scope: ObjectiveDocument77 pagesProject Objectives and Scope: Objectivesupriya patekarNo ratings yet

- Commissioner Rehns SpeechDocument15 pagesCommissioner Rehns SpeechLuis LavayenNo ratings yet

- Canale Crisei 2013Document12 pagesCanale Crisei 2013rorita.canaleuniparthenope.itNo ratings yet

- Considerations Regarding Monetary and Fiscal Exit Strategies From The CrisisDocument5 pagesConsiderations Regarding Monetary and Fiscal Exit Strategies From The CrisisDănutsa BănişorNo ratings yet

- The Euro Crisis: It Isn'T Just Fiscal and It Doesn'T Just Involve GreeceDocument37 pagesThe Euro Crisis: It Isn'T Just Fiscal and It Doesn'T Just Involve GreecePuneet GroverNo ratings yet

- HE Uropean Entral Bank in THE Crisis: S E L HDocument7 pagesHE Uropean Entral Bank in THE Crisis: S E L HyszowenNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Cyclicality and EMUDocument13 pagesFiscal Cyclicality and EMUPetros NikolaouNo ratings yet

- JPF Teamwork Eurozone FT 310805Document3 pagesJPF Teamwork Eurozone FT 310805BruegelNo ratings yet

- Speech Thomas Leysen IBEC - CEO Conferentie Economisch en Monetair Beleid in Europa: Naar Een Goede BalansDocument7 pagesSpeech Thomas Leysen IBEC - CEO Conferentie Economisch en Monetair Beleid in Europa: Naar Een Goede BalansKBC EconomicsNo ratings yet

- Europe Under StressDocument4 pagesEurope Under StressurbanovNo ratings yet

- Occ Asional Paper Series: The Benefits of Fiscal Consolidation in Uncharted WatersDocument37 pagesOcc Asional Paper Series: The Benefits of Fiscal Consolidation in Uncharted WatersSofia Escária100% (1)

- Stabilization Policy EurozoneDocument28 pagesStabilization Policy EurozoneafzalNo ratings yet

- Italy and Europe - WEFDocument15 pagesItaly and Europe - WEFcorradopasseraNo ratings yet

- Ten Commandments Fiscal Adjustment Advanced EconomiesDocument21 pagesTen Commandments Fiscal Adjustment Advanced EconomiesMandy WeaverNo ratings yet

- Unconventional Monetary Policy Measures - A Comparison of The Ecb, FedDocument38 pagesUnconventional Monetary Policy Measures - A Comparison of The Ecb, FedDaniel LiparaNo ratings yet

- The Future of The Euro PDFDocument28 pagesThe Future of The Euro PDFVictor Fuentes LastiriNo ratings yet

- Debt Reduction Without DefaultDocument13 pagesDebt Reduction Without DefaultitargetingNo ratings yet

- Euro Zone Stability PactDocument6 pagesEuro Zone Stability PactArlene BlumNo ratings yet

- Monetary and Fiscal Policy in The Euro AreaDocument17 pagesMonetary and Fiscal Policy in The Euro Areausman098No ratings yet

- OECD 2010 paper examines counter-cyclical economic policiesDocument9 pagesOECD 2010 paper examines counter-cyclical economic policiesAdnan KamalNo ratings yet

- !!! Macroeconomics and Stagnation - Keynesian-Schumpeterian WarsDocument7 pages!!! Macroeconomics and Stagnation - Keynesian-Schumpeterian Warsalcatraz2008No ratings yet

- The End Game Is Debt SustainabilityDocument2 pagesThe End Game Is Debt SustainabilityBruegelNo ratings yet

- 06iie3748 RubinomicsDocument48 pages06iie3748 Rubinomicsbagus kuncoro hadiNo ratings yet

- International Monetary and Financial Committee: Twenty-Seventh Meeting April 20, 2013Document5 pagesInternational Monetary and Financial Committee: Twenty-Seventh Meeting April 20, 2013projectdoublexplus2No ratings yet

- Working Paper Series: Macroeconomic Stabilization, Monetary-Fiscal Interactions, and Europe's Monetary UnionDocument28 pagesWorking Paper Series: Macroeconomic Stabilization, Monetary-Fiscal Interactions, and Europe's Monetary UnionTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Monitoring Macro Economic Imbalances in Europe Proposal For A Refined Analytical FrameworkDocument16 pagesMonitoring Macro Economic Imbalances in Europe Proposal For A Refined Analytical FrameworkBruegelNo ratings yet

- Fiscal PolicyDocument7 pagesFiscal PolicySara de la SernaNo ratings yet

- European Semester Thematic Factsheet Public Finance Sustainability enDocument13 pagesEuropean Semester Thematic Factsheet Public Finance Sustainability ensosia7No ratings yet

- Economic Crises and Structural Reforms in Southern Europe. IntroductionDocument13 pagesEconomic Crises and Structural Reforms in Southern Europe. IntroductionPaolo ManasseNo ratings yet

- Managing Director: Charles H. Da ADocument3 pagesManaging Director: Charles H. Da Aakis7415No ratings yet

- Euro ZoneDocument12 pagesEuro ZoneUnnikannan P NambiarNo ratings yet

- Undertaking A Fiscal ConsolidationDocument24 pagesUndertaking A Fiscal ConsolidationInstitute for GovernmentNo ratings yet

- European Comission Analysis: Fiscal Consolidation and Spillovers in The Euro Area Periphery and Core.Document32 pagesEuropean Comission Analysis: Fiscal Consolidation and Spillovers in The Euro Area Periphery and Core.Makedonas AkritasNo ratings yet

- Ipol Ida (2015) 587289 enDocument112 pagesIpol Ida (2015) 587289 enاحلام سعيدNo ratings yet

- F 2807 SuerfDocument11 pagesF 2807 SuerfTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- (IMF Working Papers) Monetary Policy in Central and Eastern EuropeDocument79 pages(IMF Working Papers) Monetary Policy in Central and Eastern EuropeJorkosNo ratings yet

- JPF The Current Accounts QuandaryDocument3 pagesJPF The Current Accounts QuandaryBruegelNo ratings yet

- International Monetary and Financial Committee: Thirtieth M Eeting October 11, 2014Document21 pagesInternational Monetary and Financial Committee: Thirtieth M Eeting October 11, 2014IEco ClarinNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Budget PolicyDocument21 pagesSustainable Budget PolicyDido Sujaya PerwendhaNo ratings yet

- Regional Economic Outlook: Dealing With Shocks Evidence From Old EU Members and Serbia by Abdelmoneim YoussefDocument9 pagesRegional Economic Outlook: Dealing With Shocks Evidence From Old EU Members and Serbia by Abdelmoneim Youssefabdelmoneim_youssefNo ratings yet

- Berta-Tóth - Fiscal RulesDocument62 pagesBerta-Tóth - Fiscal Rulesdebreceni.sandor.770712No ratings yet

- Challenges For The Euro Area and Implications For Latvia: PolicyDocument6 pagesChallenges For The Euro Area and Implications For Latvia: PolicyBruegelNo ratings yet

- Greek CrisesDocument10 pagesGreek CrisesManasakis KostasNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Consolidation in A Small Euro-Area EconomyDocument38 pagesFiscal Consolidation in A Small Euro-Area EconomyPrafull SaranNo ratings yet

- Ecbwp 1697Document32 pagesEcbwp 1697TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Introduction: The Role of Central Banks in Economic Development With An Emphasis On The Recent Argentinean ExperienceDocument6 pagesIntroduction: The Role of Central Banks in Economic Development With An Emphasis On The Recent Argentinean ExperienceGeraldo Biasoto JrNo ratings yet

- Proiecte EconomiceDocument16 pagesProiecte EconomiceFlorina StoicescuNo ratings yet

- Analysing Government Debt Sustainability in The Euro Area: ArticlesDocument15 pagesAnalysing Government Debt Sustainability in The Euro Area: ArticlesinexpugnabilNo ratings yet

- Greece and The Euro CrisisDocument8 pagesGreece and The Euro CrisisRhonda BushNo ratings yet

- JUL 20 UniCredit Market SenseDocument8 pagesJUL 20 UniCredit Market SenseMiir ViirNo ratings yet

- Blanchard (2019) - Europe Must Fix Its Fiscal Rules (Project Syndicate)Document2 pagesBlanchard (2019) - Europe Must Fix Its Fiscal Rules (Project Syndicate)albirezNo ratings yet

- Iv. Fiscal Consolidation: Lessons From Past Experience: Introduction and Main ResultsDocument24 pagesIv. Fiscal Consolidation: Lessons From Past Experience: Introduction and Main ResultsfrommmarsNo ratings yet

- General Assessment of The Macroeconomic Situation: The Recovery Is Strengthening Albeit Slowly and UnevenlyDocument82 pagesGeneral Assessment of The Macroeconomic Situation: The Recovery Is Strengthening Albeit Slowly and UnevenlygbbajajNo ratings yet

- Chipping Away at Public Debt: Sources of Failure and Keys to Success in Fiscal AdjustmentFrom EverandChipping Away at Public Debt: Sources of Failure and Keys to Success in Fiscal AdjustmentRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Easy Java AgarapAbienFred2015Document50 pagesEasy Java AgarapAbienFred2015Muhammad Khalid100% (2)

- Introduction to Programming Using Java Version 5.0Document699 pagesIntroduction to Programming Using Java Version 5.0Ogal Victor100% (1)

- Understanding Hormone Highs and Lows PhoDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Hormone Highs and Lows PhoБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- International Macroeconomic Environment: Weaker Global Growth and Geopolitical Tensions Rekindle Financial Sector VolatilitiesDocument11 pagesInternational Macroeconomic Environment: Weaker Global Growth and Geopolitical Tensions Rekindle Financial Sector VolatilitiesБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- 300 53 MacGregor Bulk SwedenDocument1 page300 53 MacGregor Bulk SwedenБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of The Economic Impact of Brexit On The EU27Document60 pagesAn Assessment of The Economic Impact of Brexit On The EU27gttrans111No ratings yet

- Visual Basic Brief IntroDocument48 pagesVisual Basic Brief IntroheloverNo ratings yet

- The Worst Slide Deck Ever: Jgross@ist - Psu.eduDocument9 pagesThe Worst Slide Deck Ever: Jgross@ist - Psu.eduБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- BergerHerz GmuDocument33 pagesBergerHerz GmuБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- 8 Ekonomski Vjesnik 2014 1 Ferencak Crnkovic RudanDocument14 pages8 Ekonomski Vjesnik 2014 1 Ferencak Crnkovic RudanБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- Brochure - Loading Spout - Pubc-0499-AulDocument2 pagesBrochure - Loading Spout - Pubc-0499-Aulm_verma21No ratings yet

- He's Just Not That Into You (The Movie Script)Document119 pagesHe's Just Not That Into You (The Movie Script)Adesti KomalasariNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of FEDocument9 pagesA Brief History of FEБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- Optimum Currency Areas and The European Experience: ECO41 International Economics Udayan RoyDocument57 pagesOptimum Currency Areas and The European Experience: ECO41 International Economics Udayan RoyБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- Italian Way to Fiscal Federalism ExplainedDocument55 pagesItalian Way to Fiscal Federalism ExplainedБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- ZeolitesDocument35 pagesZeolitesRizwan Khan100% (2)

- FdiDocument51 pagesFdipplahaneNo ratings yet

- Czech Republic's Competitiveness During Times of Creative DestructionDocument58 pagesCzech Republic's Competitiveness During Times of Creative DestructionБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- Second Generation Fiscal FederalismDocument67 pagesSecond Generation Fiscal FederalismCristhian Pinto RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Introduction: "European" Fiscal FederalismDocument26 pagesChapter 1 Introduction: "European" Fiscal FederalismБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- KukiDocument1 pageKukiБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- Arestis SawyerDocument21 pagesArestis SawyerБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- сдфсфDocument282 pagesсдфсфБежовска СањаNo ratings yet

- The Role of Instituions in Asian DevelopmentDocument32 pagesThe Role of Instituions in Asian DevelopmentCahyo NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Retail Business Report On Spar PakistanDocument46 pagesRetail Business Report On Spar Pakistan868ndpfy56No ratings yet

- MSI22 OnlinedistributionDocument28 pagesMSI22 Onlinedistributionsunnyn1No ratings yet

- Lesson 3 Module Market IntegrationDocument10 pagesLesson 3 Module Market IntegrationTon TonNo ratings yet

- Top Ten Reasons To Oppose The IMF - Global ExchangeDocument4 pagesTop Ten Reasons To Oppose The IMF - Global ExchangeAmin Adi AffandiNo ratings yet

- FRENCH NEORREALIST Magara2014Document442 pagesFRENCH NEORREALIST Magara2014Liber Iván León OrtegaNo ratings yet

- UAE's Management of Global Economic ChallengesDocument26 pagesUAE's Management of Global Economic ChallengesEssa SmjNo ratings yet

- WTO Role in Facilitating Global TradeDocument17 pagesWTO Role in Facilitating Global TradeReshma RaoNo ratings yet

- LAC CFS 2017 Costa Rica ENDocument4 pagesLAC CFS 2017 Costa Rica ENMichaelNo ratings yet

- I B A G: Nternational Usiness in AN Ge of LobalizationDocument16 pagesI B A G: Nternational Usiness in AN Ge of LobalizationrajivaminranaNo ratings yet

- Banking MCQ by Mahindra PDFDocument57 pagesBanking MCQ by Mahindra PDFHaseebNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Strongest and Most Powerful International Organizations in The World 2022Document7 pagesTop 10 Strongest and Most Powerful International Organizations in The World 2022Rieva Jean PacinaNo ratings yet

- Communique Third G20 FMCBG Meeting 9 10 July 2021Document6 pagesCommunique Third G20 FMCBG Meeting 9 10 July 2021Aristegui NoticiasNo ratings yet

- L6 Globalisation and The Neoliberal StateDocument52 pagesL6 Globalisation and The Neoliberal StatechanchunsumbrianNo ratings yet

- Myanmar's Automotive Industry Development Policy (2019Document62 pagesMyanmar's Automotive Industry Development Policy (2019wineNo ratings yet

- Financial Oligarchy and The Crisis: Simon Johnson MITDocument10 pagesFinancial Oligarchy and The Crisis: Simon Johnson MITJack LintNo ratings yet

- GEC 8 The Contemporary WorldDocument68 pagesGEC 8 The Contemporary WorldMay MedranoNo ratings yet

- Impact of IMF On Pakistan Economy: 17221598-144 (Neha Durani) 17221598-154 (Saira Irtaza) 17221598-145 (Fizba Tahir)Document46 pagesImpact of IMF On Pakistan Economy: 17221598-144 (Neha Durani) 17221598-154 (Saira Irtaza) 17221598-145 (Fizba Tahir)Neha KhanNo ratings yet

- Last Assignment BWCS by Bilal AkbarDocument102 pagesLast Assignment BWCS by Bilal AkbarBrainiac MubeenNo ratings yet

- International Political Economy: R. FalknerDocument40 pagesInternational Political Economy: R. FalknerJuan Esteban Arratia SandovalNo ratings yet

- Economic Development. CHAPTER 15Document8 pagesEconomic Development. CHAPTER 15Mica Joy GallardoNo ratings yet

- International Political Economy NotesDocument52 pagesInternational Political Economy NotesTal100% (6)

- Capital Market Development in UgandaDocument83 pagesCapital Market Development in UgandaThach Bunroeun100% (1)

- What AI Means For Economics - by IMFDocument81 pagesWhat AI Means For Economics - by IMFtamlqNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2018-2019Document46 pagesAnnual Report 2018-2019Sabikul SabikNo ratings yet

- The Relationships Between Microfinance, Capital Flows, Growth, and Poverty AlleviationDocument3 pagesThe Relationships Between Microfinance, Capital Flows, Growth, and Poverty AlleviationPierre Raymond BossaleNo ratings yet

- Economic Environment of BusinessDocument8 pagesEconomic Environment of BusinessBhawna KhuranaNo ratings yet

- Angol Szakmai Szobeli TetelekDocument19 pagesAngol Szakmai Szobeli Tetelekgiranzoltan100% (1)

- Financial crises caused by cross-border investment flows not misbehaviorDocument4 pagesFinancial crises caused by cross-border investment flows not misbehavioralpar7377No ratings yet

- Pi Global Talent Trends 2023 v11Document54 pagesPi Global Talent Trends 2023 v11lefkisNo ratings yet