Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Comment - 2011 - Revisiting The Illiquidity Discount For Private Companies, A Skeptical

Uploaded by

jpkoningOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Comment - 2011 - Revisiting The Illiquidity Discount For Private Companies, A Skeptical

Uploaded by

jpkoningCopyright:

Available Formats

VOLUME 24

|

NUMBER 1

|

WI NTER 2012

APPLI ED CORPORATE FI NANCE

Journal of

A MORGAN S TANL E Y PUBL I CAT I ON

In This Issue: Liquidity and Value

Financial Markets and Economic Growth

8 Merton H. Miller, University of Chicago

A Look Back at Merton Millers Financial Markets and Economic Growth

14 Charles W. Calomiris, Columbia Business School

Liquidity, the Value of the Firm, and Corporate Finance

17 Yakov Amihud, New York University, and Haim Mendelson,

Stanford University

Getting the Right Mix of Capital and Cash Requirements

in Prudential Bank Regulation

33 Charles W. Calomiris, Columbia Business School

CARE/CEASA Roundtable on Liquidity and Capital Management

42 Panelists: Charles Calomiris, Columbia Business School;

Murillo Campello, Cornell University; Mark Lang, University

of North Carolina; and Florin Vasvari, London Business School.

Moderated by Scott Richardson, London Business School.

Statement of the Financial Economists Roundtable

How to Manage and Help to Avoid Systemic Liquidity Risk

60 Robert Eisenbeis, Cumberland Advisors

Clearing and Collateral Mandates: A New Liquidity Trap?

67 Craig Pirrong, University of Houston

Transparency in Bank Risk Modeling:

A Solution to the Conundrum of Bank Regulation

74 David P. Goldman, Macrostrategy LLC

Revisiting the Illiquidity Discount for Private Companies:

A New (and Skeptical) Restricted-Stock Study

80 Robert Comment

Are Investment Banks Special Too? Evidence on

Relationship-Specifc Capital in Investment Bank Services

92 Chitru S. Fernando and William L. Megginson,

University of Oklahoma, and Anthony D. May,

Wichita State University

80 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

Revisiting the Illiquidity Discount for Private Companies:

A New (and Skeptical) Restricted-Stock Study

1. Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993). 2. For additional discussion of the discount rates used in fairness opinions, see Robert

Comment, Business Valuation, DLOM and Daubert: The Issue of Redundancy, Busi-

ness Valuation Review, 29 (2010).

B D

by Robert Comment

ata from studies of restricted stock are routinely

used by business-valuation analysts and apprais-

ers when valuing private companies to estimate

liquidity discounts, often referred to as discounts

for lack of marketability, or DLOMs. Te standard rationale

for this use of DLOMs is that an asset that is hard to sell must

be worth less, all other things equal, than an asset that is

easier to sell. DLOMs as high as 20% to 40% are commonly

used in practice for valuing small private businesses. (Low

valuations are advantageous for some parties in gift-tax and

divorce matters.)

Te evidence supporting the use of such large DLOMs

comes from so-called restricted-stock studies that analyze

the average percentage price discount (market price less deal

price) seen in private placements of restricted stock (stock

not registered with the SEC for resale to the public). But

these studies, as I discuss in this paper, are badly awed. And

insofar as hard to sell is treated as a type of risk, any supple-

mental adjustment for illiquidity is potentially redundant; it

amounts to a discounting for risk that is already reected in

the core valuation to which a supplemental adjustment, such

as a DLOM, is applied. Te evidence from my own study,

which is summarized in the pages that follow, is consistent

with use of a DLOM no larger than 5-6%.

Large DLOMs have also been used by accountants when

determining the compensation expense associated with grants

of equity. In this case, the justication is largely theoretical.

Te large DLOM is calculated as the value of a put option

that protects its owner against all downside risk (with the

value of the put expressed as a percentage of total value).

Te intuition, if one can call it that, is that an elimination of

downside risk mitigates the inconvenience of illiquidity. Te

put estimate is based on the volatility of free-trading shares,

perhaps based on comparable public companies, along with

an estimate of the expected time before a liquidity event.

But this option-based approach is overkill at best, and adds

nothing to the purported empirical support for large DLOMs.

Accordingly, in public disclosures, corporate executives would

be well advised to characterize any double-digit DLOMs used

in fair-value estimates as assumptions based on managements

highly speculative judgment, and not on hard evidence.

Many business valuations are produced for the eyes of

a judge in a prospective future legal proceeding. Since the

Supreme Courts ruling in Daubert,

1

all federal judges (and by

now most state judges) are obliged to exclude expert opinion

that is not reliable. While judges have been slow to impose

Daubert standards on business-valuation methods, perhaps in

the belief that valuation is necessarily as much art as science,

such judicial forbearance is unlikely to last. One takeaway

from this paper is that a valuation that includes a large

DLOM based on evidence from studies of restricted stock

may not provide the anticipated degree of legal comfort.

Specically, judges have not yet addressed the likely

redundancy of large DLOMsa redundancy that results in

a double discounting for the risk reected in a core valua-

tion methodology like discounted cash ow (DCF) analysis.

In practice, discount rates depend strongly on the size of

the company being valued, with higher rates being used

for smaller companies. But it also happens to be true that

company size is highly correlated (across companies) with

liquidity or marketabilityan empirical regularity that has

been shown to hold using almost every measure of size and

liquidity. Because the eective size premium in discount rates

is large, there is a large discount for lack of size (DLOS)

embedded in core valuation methodologies. Because size and

marketability are highly correlated, a large DLOM is likely

to amount to just a second DLOS by another name, where

the rst DLOS is ample.

Just how ample eective size premiums tend to be can be

seen in the discount rates used in the fairness-opinion valua-

tions that investment bankers produce in support of their

M&A transactions.

2

Table 1 shows the average discount rates

used in a random sample of 700 DCF valuations produced

during 2007-2010 and publicly disclosed in an SEC ling,

most often in a proxy statement for a shareholder vote to

approve a merger. Tese 700 DCF valuations were produced

by a total of 162 investment banks and valuation rms, with

the four most active rms (Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan,

Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley) producing one-quarter

of the total. Each valuation uses a range of discount rates, so

81 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

3. See Viral V. Acharia and Lasse Heje Pedersen, Asset Pricing with Liquidity Risk,

Journal of Financial Economics, 77 (2005).

4. See Table 4 in Mukesh Bajaj, David Denis, Stephen Ferris and Atulya Sarin, Firm

Value and Marketability Discounts, Journal of Corporation Law, Vol. 27 (2001).

5. An extreme example where buyer skepticism may have played a role is the private

placement by the development-stage pharmaceutical company HST Global, Inc., which

sold restricted stock without registration rights in August 2008. The new shares, which

amounted to 4% of shares outstanding, were sold to 22 buyers at a price of $1.25/

sharea discount of 86% off the (OTCBB) trading price on the day the deal closed. That

market benchmark had risen over the prior 30 calendar days from $3.59 per share to

$8.98 per share, or by 150%.

6. The known or potential rate of error is one indicia of reliability cited by the Su-

preme Court in its Daubert ruling governing the admissibility of expert testimony. See

Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

My study avoids four mistakes that are routinely made by

studies of the liquidity discounts seen in private placements

of restricted stock.

First and foremost, it is a mistake to assume that discounts

in private placements of restricted stock are attributable solely

to restricted marketability since discounts also occur in private

placements of free-trading shares. My data include free-trading

shares (28% of all deals) as well as restricted stock. Only the

dierential discount can be attributed to the restricted nature

of restricted stock, and then only after controlling for deter-

minants of discounts that are common to restricted stock and

free-trading shares. But, as discussed below, my own and other

studies have shown that actual discounts depend little on the

restricted nature of restricted stock.

Second, one long dominant feature of the private-place-

ment landscape has been the high participation by OTC

companies (those with Pink-Sheet or OTCBB-traded shares).

OTC companies account for 41% of the 1,103 private place-

ments of common stock during 2004-2010 (that are included

in my data). Tis is down from 82% of 88 deals during the

period 1990-1995.

4

Tis matters because almost all of the

largest discounts (those above 50%) in my data occur in deals

by OTC companies. Te prevalence of OTC deals means

that discounts are often calculated relative to market prices

that are set in trading venues that are not often thought of

as ecient markets. It is a mistake to overlook the eect of

OTC status, especially insofar as such data provide the juice

of the analysis.

Te third mistake is related to the second. It is a mistake

to overlook the change in the market price of the stock over

the several weeks before the deal. Te rationale is straight-

forward. Buyers may be skeptical about a market price, and

discount more heavily o that market price to compensate

for any recent increases.

5

Consistent with this possibility, the

percentage change in stock price over the 30 days before the

deal closes explains private-placement discounts as well as any

other explanatory variable that I consider.

Fourth, the dispersion in discounts from one deal to the

next is wide and it may be tempting to overlook this attribute

of private-placement discounts when reaching conclusions.

It is because the dispersion is wide, however, that it is impor-

tant to address this feature of the data.

6

Because t-statistics

increase with sample size, statistical signicance presents a

low bar in a sample as large as mine.

One nal mistake: it is wrong to assume that an average

discount reects blockage (a practical rather than regulatory

Table 1 reports the average high and average low. Te eective

size premium is simply the dierence in the discount rates

deemed appropriate for the smallest versus largest companies

(row D minus row A in Table 1), which comes to 7.6% based

on the low and 10.0% based on the high, or 8.8% overall.

While size and liquidity are correlated, a size premium this

large cannot be plausibly attributed to a dierence in liquidity

alone. In one model, illiquidity contributes 4.6% per year to

the dierence in annual risk premium between stocks with

low versus high liquidity.

3

Compared to this estimate, the

eective size premium of 8.8% seen in Table 1 should be

sucient to address liquidity risk.

Finally, the size premium in an annual discount rate can

be made comparable to a DLOM by converting it arithmeti-

cally into a one-time, up-front discount for lack of size, or

DLOS. Based on either the high or low rates in Table 1 and

using a Gordon growth model with an assumed growth rate

of 3%, the typical embedded DLOS approximates 53% of

total value (such as the result of a DCF valuation). Tat the

DLOS typically embedded in core valuation methods is this

large suggests that there is little remaining justication for a

DLOM of any signicance.

Ideally, the size premium in the discount rate used in a

DCF valuation should mimic a market-based size premium.

Similarly, because it uses market data, a restricted-stock

study holds the possibility of identifying an incremental,

non-redundant DLOM. Tis is because the market price

against which the price discount is measured already reects

a DLOS. Unfortunately, while a DLOM estimated in a

restricted-stock study is inherently incremental, this benet

easily can be oset by an otherwise awed methodology.

Size of Company Being Valued:

(based on deal terms)

Discount Rate

Number Average Low Average

High

A $1 Billion or more 224 9.7 11.8

B $200 to $999.9 Million 214 12.2 15.1

C $50 to $199.9 Million 141 15.8 19.4

D $0 to $49.9 Million 121 17.3 21.8

All Valuations 700 13.0 16.0

Table 1 Average Discount Rates Used in Fairness-

Opinion Valuations, Classifed by Size of

Company, 2007-2010

82 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

7. Karen Wruck, Equity Ownership Concentration and Firm Value, Journal of Finan-

cial Economics, Vol. 23 (1989); William Silber, Discounts on Restricted Stock: The

Impact of Illiquidity on Stock Prices, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 47 (1991); Mi-

chael Hertzel and Richard Smith, Market Discounts and Shareholder Gains For Placing

Equity Privately, Journal of Finance, Vol. 48 (1993); Mukesh Bajaj, David Denis, Ste-

phen Ferris and Atulya Sarin, Firm Value and Marketability Discounts, Journal of Cor-

poration Law, Vol. 27 (2001); and Michael Barclay, Clifford Holderness and Dennis

Sheehan, Private Placements and Managerial Entrenchment, Journal of Corporate Fi-

nance, Vol. 13 (2007).

8. See Table 5 of Mark Huson, Paul Malatesta and Robert Parrino, The Decline in the

Cost of Private Placements, working paper available at SSRN.com (June 2009).

9. Report of the Advisory Committee on the Capital Formation and Regulatory Pro-

cess, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, July 24, 1996. (I served as the staff

economist for the Wallman Committee.)

10. I understand that the change to six months applied retroactively to existing re-

stricted stock. Accordingly, absent an effective registration, restricted stock issued before

August 15, 2007 converted into free-trading shares no later than February 15, 2008,

while restricted stock issued between August 15, 2007 and February 15, 2008 con-

verted after six months.

11. See Mark Mitchell and Mary Norwalk, Assessing and Monitoring the Reliability

of Marketability Discount Studies and the 7.23% Solution, Business Valuation Review,

Vol. 27 (2008).

of common stock by seasoned public companies that are

current in their periodic lings.

9

Te Committees recom-

mendations coincided with the start of electronic ling, a

change that made periodic lings far more accessible. Tese

developments led the SEC to begin a gradual deregulation

to facilitate post-IPO issuances of common stock. One facet

was a modest lowering of the threshold to qualify for the use

of shelf registration, with the result that the current thresh-

olds mainly exclude OTC companies with a public oat

below $75 million. Earlier, during the period 1992-2007, all

companies with oat below $75 million had been excluded.

More importantly, the SEC shortened the minimum holding

period before restricted stock could be resold to the general

public without registration. Te regulatory holding period

was reduced from one year to six months as of February 15,

2008,

10

after being reduced from two years to one year in

early 1997.

The Mists of Time

One might imagine that the private placements most reveal-

ing about and representative of the DLOM were those before

1997, when the regulatory holding period was longest. Te

catch is that these deals mostly pre-date electronic ling,

which was phased in around 1995. Information about these

deals is limited to what issuers disclosed in press releases. If

better information was available at the time, it would have

been in disclosure documents stored on microche at SEC

headquarters. Te press releases are vague about the initial

and subsequent registration status of shares being sold.

11

Because of these data limitations, it appears to be dicult to

determine in these deals if a marketability restriction applied

for the full two-year term, or if one ever applied at all.

In any event, these older data are of dubious relevance

in the modern era. For one thing, the frequency of deals has

increased ten-fold, from 15 per year during 1990-1995 to 158

per year during 2004-2010. Buy-side competition, along with

the shift in composition away from OTC companies, may

have reduced discounts over time.

Even if a longer period confers a theoretical advantage

on pre-1997 data, these data are fuzzy, whereas a study using

modern data can use exact information, including the date

when restricted stock converts into free-trading shares. One of

my regression analyses nds that discounts in placements of

restricted stock vary little with the realized delay before free-

or contractual drag on marketability). Te most immediate

reason for this is that the shares sold in private placements are

not usually sold as a single block. Te buyers often number

in double digits. As a consequence, the size of the whole deal

(the macro block) is very dierent from the average size of

the blocks actually purchased (mini-blocks).

While my study is novel in several respects, it largely

follows a line of economic research on private-placement

discounts.

7

Te latest work in this line, a study by Mark

Huson, Paul Malatesta and Robert Parrino,

8

uses multiple

regression analysis and a large sample to estimate a dierential

discount for restricted stock after controlling for 15 other

explanatory variables. While the DLOM is not their focus,

they nd that the part of the discount directly attributable to

the regulatory restriction (which can be viewed as an estimate

of the DLOM) is 2.6% over their whole sample period, falling

from 4.8% during 1995-2001 to -0.5% during 2002-2007.

Tese estimates are somewhat lower than what I nd during

2004-2010.

SEC Deregulation

Te Securities Act of 1933 requires that companies sell stock

to the general public only after ling a registration state-

ment that discloses material information deemed necessary

to level the playing eld. Having said that, companies are

allowed to sell their securities without registration and the

investor protections associated with a prospectus, just not to

the general public. Common stock sold without registration

is known as restricted stock.

Te SEC has discouraged the sale of restricted stock

throughout its history, mainly by imposing a minimum

holding period before restricted stock can be resold to the

general public. Te social utility of this sand in the gears

deterrence was always dubious, however, given that most

purchases of shares of seasoned public companies occur in

the open market, supported by the companys periodic lings

(mainly on Forms 10-K, 10-Q and 8-K). If these disclosures

are sucient to level the playing eld, then why would (post-

IPO) buyers need registration, sta review, and a prospectus

when the seller happens to be the company rather than

another investor?

Applying this logic, a blue-ribbon advisory panel

convened by the SEC and known as the Wallman Committee

recommended in 1996 that the SEC deregulate the issuance

83 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

12. See Bernardo Bortolotti, William Megginson and Scott B. Smart, The Rise of

Accelerated Seasoned Equity Underwritings, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Vol.

20 (2008).

the buyers in private placements of free-trading shares. For

instance, the prospectus supplement led by Orthovita, Inc.

in July 2007 lists the buyers in its private placement of free-

trading shares, a group that includes one natural person, one

investment bank, and ve mutual funds or hedge funds. A

common clientele is not surprising since the same placement

agents handle either type of deal.

Table 2 reports the distribution of deals by the delay

before conversion, and does so separately for deals with and

without registration rights. It takes longer to accomplish free-

trading status without registration rights, as expected, but

registration rights do not eliminate delay. Te data in Table 2

show that quick registrations (in 90 days or less) rarely happen

without registration rights. If you do not have a shelf in place

but think a quick registration is feasible because your public

disclosures are complete and you face a level playing eld, you

might as well grant registration rights and reap the benet of

a (slightly) lower discount.

Blockage Discounts

Te fact that three-quarters of all the common stock of U.S.

public companies is held by institutional investors makes

the possibility of blockage discounts implausible as a general

matter. (A blockage discount at time of purchase anticipates

that exiting the investment through retail sales will drive

down the market price before the sale can be completed.)

But since institutional investors (even small-cap mutual

funds) avoid OTC stocks, blockage discounts are possible

for these smallest of small-cap stocks. In theory, then, since

OTC companies have been responsible for the lions share of

all private placements of common stock, part of the average

discount reported by past studies of restricted stock could

represent a blockage discount akin to a DLOM. But the

evidence for this discount, insofar as it assumes that there is

just one buyer per deal, is highly questionable.

trading status obtains. Te insensitivity of average discounts

to the length of the regulatory holding period suggests

that data originating in the distant past when the regula-

tory restriction was most severe oer no real advantage over

modern data, whereas modern data oer the considerable

advantage of timeliness.

Free-Trading Shares

Technically, it is the issuance and resale of shares that is regis-

tered. Because the shares themselves are not, I use the term

free-trading shares rather than registered shares. Private

placements of free-trading shares take place after a shelf registra-

tion, a type available since 1982. Although some underwritten

equity oerings resemble private placements,

12

my sample of

private placements of free-trading shares does not include any

underwritten oerings. A shelf-registration diers in that it

authorizes generic, future issuances rather than one specic,

immediate issuance. For example, IMAX Corp. stated in its

shelf ling in 2009 that: We may oer and sell, from time to

time in one or more oerings, any combination of debt and

equity securities that we describe in this prospectus having an

aggregate initial oering price of up to $250 million.

So, once the SEC has declared eective a shelf registra-

tion that includes boilerplate language describing the legal

attributes of the registrants common stock and sets a dollar

maximum, the registrant may sell free-trading shares in

subsequent private placements without further regulatory

permission or review. Being generic, a shelf-registration ling

does not include deal-specic information. Tat gets disclosed

in a prospectus supplement led later, at time of sale, which

can be several years later.

While the buyers of private placements of free-trading

shares need not be accredited investors, they mostly are. Te

same sort of institutions and wealthy individuals that are the

buyers in private placements of restricted stock appear to be

All Deals With Registration Rights Without Registration Rights

N % N % N %

Free Trading Immediately 307 28 0 0 0 0

Free Trading in 9 to 90 Days 198 18 194 42 4 1

Free Trading in 91 to 183 Days 352 32 149 32 203 61

Free Trading in 184 to 365 Days 246 22 118 26 128 38

All Deals 1,103 100 461 100 335 100

Table 2 Distribution of Delay Before Free-Trading Status Occurs,

Classifed by Whether the Buyers Receive Registration Rights

84 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

13. I was able to identify the exact number of buyers in 57% of all deals, either from

a count reported in the initial disclosure on Form 8-K or in a follow-on registration state-

ment where the buyers in the earlier placement are all named and thus countable. Also,

where no specifc count of buyers is provided, disclosure documents nevertheless refer to

the buyers using the singular or plural tense.

as a percentage of prior shares outstanding) as an explanatory

variable in my multiple regression, but not as a measure of

potential blockage. I see it instead as a measure of potential

dilution. Dilution will depend partly on how many shares

are sold and partly on the size of the discount. But since

one cannot use the discount itself to construct an explana-

tory variable, I settled for a measure of potential rather than

actual dilution.

While dilution is a better explanation for why discounts

might depend on deal size, it is not a simple explanation. One

would not expect discounts to depend on potential dilution

if (1) the size of the deal is disclosed before the time when

the discount is measured and (2) the market price quickly

and fully reects the mix of public information. Under these

conditions, the potential for dilution should be reected

equally in the market price and the deal price and net out

the calculated discount. I was unwilling to assume that these

two conditions hold routinely in my data. Also, there may be

other explanations besides blockage or dilution.

Why Regression Analysis?

When nancial economists study private-placement discounts,

it is standard practice to use multiple regression analysis to

estimate the eect of the regulatory restriction as a dieren-

tial discount. In contrast, when business-valuation analysts

produce restricted-stock studies, it has been standard practice

to limit the sample to restricted stock in order to sustain the

assumption that the regulatory restriction is the sole cause of

the average discount and the associated assumption that the

unconditional average discount constitutes a valid estimate

of the DLOM. Moreover, with this setup, one can further

maintain that every variable that correlates with discounts

necessarily tells a story about the DLOM. Tis is all problem-

Most private placements of common stock are sold to

groups of accredited investors who are assembled by private-

placement agents for nders fees. Te individual members of

the groups seem to be unrelated except in the sense that some

participating mutual or hedge funds have a common money

manager. It is unlikely that group members would eventually

sell in unison. Tey are unlikely to seek to exit their invest-

ments at the same time, and unlikely to conspire to ood the

market with coordinated sales if doing so will reduce their

sale proceeds.

Table 3 compares the average number of shares sold per

deal to the average number of shares sold per buyer.

13

Each

is expressed as a percentage of the number of pre-sale shares

outstanding and, alternatively, as a percentage of the trading

volume in the market during the last full calendar month

before the close of the sale.

Private placements were sold to a single buyer just 18%

of the time (201 of 1,103). Te size of the macro-block has

actually been an inverse proxy for the size of the typical mini-

block in that the smallest mini-blocks are associated with the

largest macro-blocks. In other words, as the number of shares

sold increases from one deal to the next, the number of buyers

tends to increase even more. In the extreme, in cases with 10

or more buyers, the total shares sold averaged 22.1% of prior

shares outstanding while the typical block sold averaged 0.9%

of prior shares outstanding. Similarly, when there were 10 or

more buyers, the total shares sold typically amounted to over

200% of one months volume while the typical mini-block

amounted to 9% of one months volume. A discrepancy this

great means that any correlation between discounts and the

overall size of the deal, the macro-block, cannot be indicative

of a blockage discount.

I nevertheless included the shares sold per deal (expressed

Buyers

Per Deal:

Number

of Deals

As a % of Shares Outstanding As a % of 1 Months Volume

Mean

Per Deal

Mean

Per Buyer

Median

Per Deal

Median

Per Buyer

1 201 7.9 7.9 104 104

2 9 183 13.2 3.6 214 55

10 or more 242 22.1 0.9 201 9

N/A, but >1 477 15.1 182

All Deals 1,103 14.9 176

Table 3 Shares Sold Per Deal versus Shares Sold Per Buyer

Classifed by number of buyers, alternatively expressed as a percentage of shares outstanding

and as a percentage of trading volume during the calendar month before the deal closed.

85 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

14. For a primer on multiple regression analysis, see Daniel Rubinfeld, Reference

Guide on Multiple Regression in Reference Manual on Scientifc Evidence, 2nd Edition,

2000, Federal Judicial Center. (A 3rd edition is forthcoming.)

15. Registration rights often oblige the issuer to use its best efforts or commer-

cially reasonable efforts to cause a registration statement to be declared effective by the

SEC. A registration-rights agreement can be diffcult to enforce insofar as issuers statu-

tory obligations regarding investor protection trump any obligation arising under a private

contract. The version of the registration-rights agreement with teeth specifes liquidating

damages that the issuer must pay at recurring intervals, regardless of effort or feasibility,

for as long as a timely registration is not accomplished.

lings. Sales of restricted stock in material amount are disclosed

on Form 8-K. While some smaller deals are disclosed only on

Forms 10-K or 10-Q (which I included when I happened

upon them), my sample came mostly from 8-K lings. Private

placements of free-trading shares are disclosed dierently in

prospectus supplements. Finally, conversions of restricted

stock into free-trading shares are disclosed in registration state-

ments led after the sale. Tese SEC lings generally disclose

whether any buyer is an aliate of the company and whether

buyers receive registration rights.

15

I excluded private placements of common stock for any

of the following reasons:

gross proceeds are below $100,000;

the deal price or the market price is below $0.10 per

share;

shares are sold for consideration other than immediate

cash;

shares are sold in a package with warrants or other

securities;

additional shares might ultimately be deliverable due

to a make-good provision;

the shares are issued upon exercise of an option to

buy;

the shares are issued pursuant to a standby equity line

atic to the extent that discounts are caused by factors other

than the regulatory restriction.

One reason that multiple regression analysis is so perva-

sive in economic research is that the estimated coecient

for any one explanatory variable is supposed to measure the

separate eect of that factor, after controlling for eects

that are statistically attributable to the other explanatory

variables included in the analysis.

14

Tis multivariate capabil-

ity addresses a problem with bivariate analyses, where variable

X proxies for variable Y and the separate eect of X on Z, if

any, is revealed only after controlling for the eect of Y on Z.

Multiple regression analysis is the recommended method in

this situation in part because it allows one to control for many

dierent Ys at once. Accordingly, the purpose of regression

analysis in the present study is to isolate the separate/direct

eect of the regulatory restriction on the average discount in

private placements after controlling for other determinants.

The Data for My Study

I analyzed 1,103 private placements of common stock that

closed over the seven-year period from January 1, 2004

through December 30, 2010. Tese deals were completed by

724 dierent companies. I found these private placements

using various keyword searches of Bloombergs archive of SEC

Restricted Stock Free-Trading Shares All Deals

Attribute: Mean Median Mean Median Mean Median

Market Capitalization 177.0 66.3 275.8 160.2 204.5 93.8

Total Assets 201.0 16.9 202.8 50.5 201.5 27.7

Cash & Short-Term Investments 13.2 2.2 28.4 16.8 17.5 4.1

Revenue (last 12 months) 141.4 5.2 281.5 9.4 180.4 6.4

Net Income (last 12 months) -7.0 -3.0 -21.0 -14.9 -10.9 -4.6

Shares Sold as a % of Prior Shares 16.0% 9.4% 12.4% 11.6% 15.0% 10.1%

Gross Proceeds of Sale 19.4 4.1 23.9 16.5 20.7 7.0

Deal Price Per Share 5.39 1.78 7.10 4.50 5.87 2.50

Change in Stock Price Over Prior 30 Days 13.8% 2.5% 2.8% -1.6% 10.7% 1.5%

Days Delay Before Free Trading 185 183 0 0

Fraction with Net Income < 0 79.8% 81.1% 80.1%

Fraction with Revenue = 0 21.2% 15.3% 19.6%

Fraction OTC 54.8% 3.9% 40.6%

Fraction with Deal Price <= $1/share 41.0% 14.7% 33.6%

Fraction with One Buyer 20.6% 12.1% 18.2%

Table 4 Attributes of 1,103 Private Placements of Common Stock, 2004-2010,

Per Deal, Classifed by Type of Deal, in $ Millions Except as Otherwise Indicated

86 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

16. In a few instances, insiders participated as buyers but were made to pay a higher

price than the other buyers (generally paying the market price without discount). In these

several instances, I include the deal but only insofar as it relates to the unaffliated buy-

ers.

17. Discounts Involved in Purchases of Common Stock (1996-1969), Institutional

Investor Study Report of the Securities and Exchange Commission, H.R. Doc. N.64, part

5, 92nd Cong., 1st Session, 1971, 2444-2456.

Te scarcity of large, well-known companies in this sample

is not surprising since such companies have operating cash ow,

ready access to debt nancing, and correspondingly less need

for external equity nancing. Consistent with this, the largest

companies in the sample tend to be master limited partnerships

and real estate investment trusts. Of the 20 companies with

the largest market capitalizations, half are MLPs or REITs.

For tax reasons, these entities pay out most of their earnings

as dividends or partnership distributions, and consequently

resemble smaller, growth companies in their reliance on exter-

nal nancing to fund new projects and expansions.

Te smallest companies are usually excluded from studies

of private-placement discounts, albeit indirectly by excluding

those with stock prices below $1 or $2 per share. Discounts

are correlated with OTC status, and only OTC companies

(and fallen angels) trade at stock prices this low. To have an

inuential explanatory variable like OTC status eectively

serve double duty as a sample-selection criterion introduces

an unneeded complication. My sample includes companies

with stock prices as low as $0.10 per share (but they must

trade on the day of the close, which excludes quite a few

OTC companies), and I then controlled for OTC status in

my regression analysis.

In sum, although my sample is large, it is unrepresentative

of the population of all companies. Most of the companies that

have done private placements of common stock are smaller,

cash-burning growth companies. Private-placement companies

are especially notable for the prevalence and size of their losses

in the year before the deal. Finally, the largest companies in

my sample (measured by market capitalization) are dispropor-

tionately MLPs or REITs. While MLPs and REITs comprise

just 46 (or 4%) of all the deals in this sample and thus have

little eect on the regression estimates reported below, these

companies comprise half of the largest 20 companies in the

sample. Accordingly, the very largest companies that do these

deals are not especially representative either.

Regression Model

The dependent variable in the regression analysis is the

private-placement discount, which compares the per-share

deal price to the prevailing market price. In calculating

the discount, I measured the prevailing market price as the

volume-weighted average price (VWAP) on the day the deal

closes. Te discount is the dierence between the deal and

market prices expressed as a percentage of the market price,

which has a positive value when the deal price is below the

market price.

In its Institutional Investor Study Report published in

1971,

17

the SEC found that restricted-stock discounts were

that gives the company the right to put shares to the purchaser

periodically at a formulaic price;

the sale constitutes a change-in-control transaction;

the buyer group includes an ofcer, director or afliate

of the selling company;

16

the buyer is a company that is a strategic partner of the

selling company;

the selling company is a bank; or

the selling companys stock does not trade on the day

the sale closes.

Te common stock sold in private placements is often

packaged with warrants (a right to buy more shares at a set

price over, typically, ve years). Warrant-sweetened deals are

more frequent than are stock-only deals. I followed standard

practice and excluded sweetened deals because there is not a

contemporaneous trading price for the warrants, and thus no

market price for the package (or unit) of shares and warrants

that a discount can be calculated against. In the alterna-

tive, one could venture to use an option-pricing formula to

value the warrant component of the package, but this would

produce a benchmark price that is based in part on a level-3

input and not solely on observed market values, meaning the

resulting estimate of the DLOM would seem to fall short of

the fair-market-value standard of value. In any event, stock-

only deals are plentiful.

Table 4 shows some of the attributes of the deals and the

companies in my sample. Te real eye-opener here is that

80% of the companies report negative net income over the

last four quarters before the deal closes, with the average

loss being $10.9 million. Losses are equally frequent for the

companies that sell free-trading shares and restricted stock,

but the average loss is three times greater among the compa-

nies that sell free-trading shares ($21.0 million) compared to

those that sell restricted stock ($7.0 million).

Te busiest of the seven years was 2007, with 21% of

all deals, while the slowest years were 2008 and 2009, each

with 11% of the total. Pharmaceutical companies accounted

for 19% of all deals, oil & gas companies 14%, manufactur-

ers 10%, medical technology 8%, non-medical technology

7%, and mining companies 5%. Smaller public companies

predominate. Of all deals, 5% were done by NYSE companies,

13% by Amex companies, 30% by NASDAQ Global Market

companies (regular Nasdaq companies), 11% by NASDAQ

Capital Market companies (the junior tier) and 41% by OTC

companies (all those not NYSE, Amex or NASDAQ). Compa-

nies that pay cash dividends comprise 6% of the sample. As

previously noted in the literature, the typical company that

sells common stock in a private placement has been a compar-

atively small, cash-burning growth company.

87 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

18. I calculate market capitalization as pre-deal shares outstanding times an average

of two market prices: the VWAP for the day 30 calendar days before the close and the

VWAP on the day of the close.

before the sale, expressed as a percentage of market capitaliza-

tion;

18

an indicator variable for negative net income;

sales revenue over the last four quarters before the sale,

expressed as a percentage of market capitalization;

an indicator variable for zero revenue;

holdings of cash, marketable securities and short-

term investments last reported before the sale, expressed as a

percentage of market capitalization.

Buyer Skepticism

Te sophisticated buyers in private placements may demand

a discount from the trading price because of skepticism about

that benchmark price. Tese variables include:

an indicator variable for OTC companies;

an indicator variable for NASDAQ Capital Market

companies (the junior tier of NASDAQ and the next closest

category to OTC status);

the percentage change in the market price over the

most dependent on (1) net income, (2) sales, (3) OTC status,

and (4) registration rights. My explanatory variables were

inspired by these four. Because my data are numerous,

however, I could employ a comparatively large number of

explanatory variables. I used 15 explanatory variables: ve as

indicators of solvency (more or less); three for buyer skepti-

cism about current prices; one for potential dilution; one for

deals done possibly not at arms length; and ve to cover

aspects of the regulatory restriction on marketability.

Ten of the 15 explanatory variables are simple indicator

variables (sometimes called dummy variables). An indicator

variable is a construct that equals one when a given condi-

tion prevails and zero otherwise. Te included explanatory

variables, and brief rationales, are as follows:

Solvency

Low solvency may weaken a companys bargaining position

when negotiating a sale price. Tese variables include:

net income (mostly losses) over the last four quarters

Regression 1 Regression 2 Regression 3

Explanatory Variable:

Coeffcient P-value Coeffcient P-value Coeffcient P-value

Intercept 6.281 0.000 4.075 0.017 3.938 0.021

Net Income as a % of Mkt. Cap. 0.045 0.000 0.045 0.000 0.044 0.000

Indicator for Net Income < 0 5.357 0.001 5.600 0.000 5.698 0.000

Revenue as a % of Mkt. Cap. -0.002 0.339 -0.002 0.271 -0.002 0.273

Indicator for Revenue = 0 4.915 0.001 4.991 0.001 5.186 0.001

Cash & STIs as a % of Mkt. Cap. -0.138 0.000 -0.130 0.000 -0.129 0.000

Indicator for OTC 13.961 0.000 11.575 0.000 11.842 0.000

Indicator for Junior Tier of Nasdaq 2.523 0.188 2.145 0.263 2.284 0.235

% Change in Market Price over 30 Days 0.107 0.000 0.105 0.000 0.105 0.000

Total Shares Sold as a % of Prior Shares 0.094 0.000 0.093 0.000 0.090 0.000

Indicator for One Buyer -8.834 0.000 -9.239 0.000 -9.147 0.000

Indicator for Restricted Stock

Sold without Registration Rights

5.238 0.006

Indicator for Restricted Stock

Sold with Registration Rights

3.464 0.021

Indicator for Free Trading in 990 Days 3.232 0.066

Indicator for Free Trading in 91183 Days 3.551 0.040

Indicator for Free Trading in 184365 Days 5.569 0.004

R-Square 0.270 0.276 0.276

Adjusted R-Square 0.264 0.268 0.268

Standard Error 18.96 18.90 18.91

Number of Observations 1,103 1,103 1,103

Table 5 Multiple Regression Analysis

Dependent Variable is Percentage Private-Placement Discount

88 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

this size. It is conventional to accept a coecient as being

signicantly dierent from zero if the P-value is at or below

0.05 or 0.10. Tese correspond to condence levels of 95%

and 90% (one minus the P-value, expressed as a percent).

Four of the ve explanatory variables that are more or less

related to company solvency (rows 2 through 6 of Table 5) are

inuential and statistically signicant. Percentage discounts

include a component of 5% to 6% if the company reports

negative net income over the four quarters before the deal,

and another 5% if the company is at a stage of development

where it has yet to generate any revenue. Tat the coecient

estimate for net income (as a continuous variable) is positive

may seem surprising at rst, but it may seem less of a surprise

when one considers (as reported in Table 4) that the losses

of companies that sell free-trading shares (at generally lower

discounts) are three times greater than the losses reported

by those that sell restricted stock. A private placement may

signal a faster-than-expected burn rate at the same time that

it reveals that funding is now in hand to keep the company

operating a while longer. But having said that, I dont claim to

understand the role that pervasive losses (the cash-burn rate)

play in determining private-placement discounts.

Te coecient for holdings of cash and short-term invest-

ments is negative, which is consistent with intuition: Te

more cash on hand, the lower the discount. More cash on

hand implies greater bargaining power, since the company is

less desperate for funding to continue its operations. Tus one

reward for better planning and more-deliberate fundraising

is a lower discount.

Two of the three explanatory variables related to buyer

skepticism about the validity or sustainability of the market

price (against which the discount is calculated) are economi-

cally and statistically significant. Statistically, the most

signicant explanatory variable (the one with the highest

t-statistic) is the percentage change in the market price during

the 30 calendar days before the closing date of the deal. Te

discount is approximately 1.1 percentage points greater for

every ten percentage points of recent run up in the market

price (and vice versa for a decline). Discounts are 11% to 14%

greater for OTC companies, depending on the regression.

Companies with stock listed in the junior tier of NASDAQ

are the closest thing to OTC companies, but are not so close

with respect to discounts and this variable explains little.

Discounts are 2% higher for companies in this category.

The explanatory variable that covers the effect of

potential dilution on discounts is the size of the deal (the

macro-block) expressed as a percentage of pre-sale shares

outstanding. Discounts are 0.9 percentage points greater

for every ten percentage points of increase in the number of

shares outstanding by virtue of the new shares that are sold.

For example, if a rm with 100 shares issues 10 new shares,

shares outstanding increase by ten percent and the discount

increases by 0.9 percentage points.

30-calendar-day period ended the day of the close, measuring

the market price by the VWAP for the day.

Potential for Dilution

As discussed in the earlier section on Blockage Discounts,

this variable is calculated as the total number of shares sold

expressed as a percentage of pre-sale shares outstanding.

Possibly Not at Arms Length

I excluded deals where the buyer is an aliate of the company,

insofar as that is disclosed, but disclosure of ulterior motives

is inherently incomplete. Beyond that, companies may reveal

positive inside information to select buyers, perhaps inappro-

priately, and want to limit the number of recipients of this

information. Tis variable is:

an indicator variable for deals sold to a single buyer.

Restricted Marketability

I measured every aspect of the marketability restriction I

could. Tese variables include:

an indicator variable for whether the shares initially

take the form of restricted stock without registration rights;

an indicator variable for whether the shares are

restricted stock with registration rights;

an indicator variable for restricted stock that ends up

converting into free-trading shares within three months (1

to 90 days);

an indicator variable for restricted stock that ends up

converting into free-trading shares in four to six months (91

to 183 days);

an indicator variable for restricted stock that ends up

converting into free-trading shares in seven to twelve months

(184 to 365 days).

For technical reasons (some of the indicator variables

just cited are a linear combination of the others), all ve of

these cannot be included as explanatory variables in the same

regression. I express certain accounting values as percentages

of market capitalization because, so scaled, their explanatory

power in the regression is much enhanced. Te rationales for

these explanatory variables are not all strong, as I err on the

side of inclusion. What matters is that none of the included

variables (and no omitted variable) be directly related to, or

a signicant proxy for, the regulatory restriction other than

the ve intended for that purpose.

Regression Results

Table 5 summarizes the results of three formulations of multi-

ple regression analysis. Te estimated coecients for most

of the control variables are statistically signicant, as would

be expected in a sample as large as this. Statistical signi-

cance is reported in Table 5 as a P-value (there is one for each

coecient estimate), which tells you whether the estimated

coecient is signicantly dierent from zero in a sample of

89 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

19. R-square is the fraction (ranging from zero to one) of the total variance in the

dependent variable that is explained in a given regression. The adjusted R-square statis-

tic differs from the raw R-square statistic in that the adjusted R-square increases only if

the added explanatory variables improve the model more than would be expected by

chance. The validity of this fnal test does not depend on the accuracy of the estimated

coeffcients of the individual explanatory variables.

Te coecient estimate reported in Table 5 that is most

relevant for the DLOM is the one (5.238) that appears in the

column labeled coecient under the heading Regression

2. After controlling for determinants of discounts unrelated

to the regulatory restriction, the portion of the typical

discount that can be tied directly to the regulatory restriction

in its most severe form is thus 5.2%, which is signicantly

dierent from zero but much smaller than conventional

DLOMs of 20% to 40%. As for the companion indicator

variable, when the regulatory restriction is mitigated through

a grant of registration rights that could serve to accelerate the

conversion of the restricted stock into free-trading shares,

discounts are 3.5% higher instead of 5.2% higher.

In Regression 3, the regulatory restriction is represented

by the realized delay before free-trading status obtains. Tis

information is not available to participants at the time of

the deal, but these data may proxy for the expectations of

the participants at the time of the deal. Discounts are 3.2%

higher when conversion occurs within 90 days, 3.6% higher

when conversion occurs within 91 to 183 days, and 5.6%

higher in the remaining cases where restricted stock ends up

converting into free-trading shares 184 to 365 days follow-

ing the close. Te last two of these estimates of the DLOM

is signicantly dierent from zero. Accordingly, discounts

depend some, though not much, on the realized delay before

the regulatory restriction is lifted.

As I explain below, data on the CD-Treasury yield spread

imply a DLOM of 2.5%. Because the DLOM on the riskless

asset can be calculated most directly, without need for multi-

ple regression analysis, the interesting statistical test is not

whether an estimate of the DLOM from a multiple regression

diers from zero, but whether it diers from 2.5%. In other

words, one concedes a DLOM of 2.5% and then asks of any

additional data whether the concession is merited.

Of the two coecient estimates in Regression 2 that

relate to the regulatory restriction, even the higher of the

two estimates, 5.2%, is not statistically signicantly dierent

from 2.5% (t-statistic of 1.44, P-value of 0.150). Likewise,

the highest of the three estimates in Regression 3 is 5.6%, an

estimate that is not statistically signicantly dierent from

2.5% (t-statistic of 1.61, P-value of 0.110).

Finally, and most importantly for my conclusions, one

can ask if the inclusion of the several explanatory variables

related to the regulatory restriction on marketability adds

to the overall explanatory power of the multiple regression

analysis. Te relevance of additional explanatory variables

is established by comparing the adjusted R-square statistics

(reported near the bottom of Table 5) of two alternative

models.

19

Discounts are around 9% lower when there is a single

buyer. Some of this may be due to sweetheart deals (oddly,

ones that favor existing shareholders, in contrast to friends

and family allocations of underpriced IPOs). While I

exclude deals known to be made with affiliated buyers,

informal relationships are commonplace among the small

companies that do private placements of common stock and

informal relationships and ulterior motives are not necessarily

disclosed. Also, as I noted earlier, lower discounts in single-

buyer deals are consistent with a desire by companies that

improperly leak positive inside information as part of a sales

pitch to limit the number of recipients of such information

to a single investor.

Regression 1 in Table 5 is the base regression, meaning

that it excludes all of the explanatory variables related to the

regulatory restriction. Tis formulation yields information

about how much of the overall variance in discounts can be

explained without any help from the explanatory variables

related to the regulatory restriction.

Regression 2 includes the indicator variable for restricted

stock sold without registration rights, along with the compan-

ion indicator variable for restricted stock sold with registration

rights. Because registration rights serve to mitigate the eects

of the regulatory restriction, the estimated coecient on the

rst of these two indicator variables (without registration

rights) should reect the eect of the regulatory restriction on

discounts more fully than will the second indicator variable

(with registration rights).

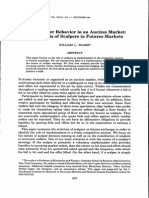

Chart 1 CD-Treasury Yield Spreads,

Monthly from June 1998 through June 2011

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

1% 2% 3% 4% 5% 6% 7%

Y

i

e

l

d

o

n

5

-

Y

e

a

r

C

D

s

Yield on 5-Year Treasuries

90 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

20. Historical data on CD yields are available from mid-1998 for several different

maturities, including the fve-year CD. My source for Treasury yields is also Bloomberg,

which offers a screen for a yield curve based on U.S. Treasury Actives from which the

yield on a hypothetical security of exactly fve years maturity can be obtained, as of any

given date, via interpolation from the actual yields on that date on Treasury notes and

bonds with remaining lives closest to fve years. Because the time of day of the CD

measure is ambiguous, I compare the CD yield on a given day to the average of the (close

of day) Treasury yields for that day and the preceding day.

21. See Susan Chaplinsky and Latha Ramchand, The Impact of SEC Rule 144A on

Corporate Debt Issuance by International Firms, The Journal of Business, Vol. 77

(2004).

22. See Yakov Amihud and Hiam Mendelson, Liquidity, the Value of the Firm, and

Corporate Finance, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Vol. 20 (2008).

buildup method of nding a discount rate for use in a DCF

valuation.

Equivalently, one can convert the CD-Treasury yield

spread into a DLOM to be applied supplementally to the

results of a core valuation methodology. An initial invest-

ment of $97,500 in the average ve-year CD would result in

approximately the same ending balance (including reinvested

interest) after ve years as would an initial investment of

$100,000 in a ve-year Treasury security. So, a CD-Treasury

yield spread of 0.5% implies a supplemental, non-redundant

illiquidity discount, or DLOM, of 2.5% (since $97,500 is

2.5% lower than $100,000).

That the DLOM on the riskless asset approximates

2.5% leads to the conclusion that any discounting for lack

of marketability beyond 2.5% constitutes a second round

of discounting for risk (where the rst round occurs in a

DCF or similar valuation). While illiquidity and the risk of

future cash ows are separate factors in valuation,

22

redun-

dant discounting represents a potential problem with any

business valuation that includes a large DLOM. As discussed

earlier, liquidity is highly correlated with company size, where

size is already an important determinant of discount rates.

So, while liquidity matters to valuation, the close association

between liquidity and company size, along with the ample

size premiums used in business valuations, mean that any

supplemental DLOM in excess of 2.5% is likely to constitute

redundant discounting.

Tat any DLOM in excess of 2.5% represents a second

round of discounting for the risk of owning a private business

frames the reliability issue. How condent can one be that a

second round of discounting for risk is not redundant to the

rst? Te evidence furnished by past restricted-stock studies

provide a questionable basis for this practice.

Conclusion

Te purpose of this study has been to determine if data on

discounts in private placements of restricted stock imply a

DLOM that is dierent from the DLOM on the riskless asset.

Tis analysis is skeptical in the sense that it is not cong-

ured, as many past studies have been, to document what is

being hypothesized and, perhaps to some degree, desired by

some interested parties. Specically, this study allocates to the

DLOM only that portion of the restricted-stock discount that

can be tied directly to restricted marketability. No portion is

allocated to the DLOM by default or presumption.

Tis approach yields estimates of the DLOM that are

no larger than 5.2% or 5.6%, which is consistent with some

Te adjusted R-square statistics for Regression 2 and

Regression 3 are both 0.268, which is remarkably close to

the adjusted R-square of 0.264 for Regression 1, the base

model with no explanatory variables related to the regula-

tory restriction on marketability. Tat only one-quarter of the

dispersion in discounts is explained by the regression analysis

reects the wide dispersion in private-placement discounts.

Tat these adjusted R-square statistics are so close (0.268

versus 0.264) means that the several explanatory variables

related to the regulatory restriction on marketability, consid-

ered as a group, add almost nothing to the explanatory power

of the base model.

DLOM on the Riskless Asset

Te DLOM on the riskless asset can be calculated from the

dierence in yields between a ve-year bank certicate of

deposit (illiquid due to penalties for early withdrawal) versus

a ve-year U.S. treasury security (highly liquid). Here, the

requisite calculations go beyond mere arithmetic only in that

one must use an average of the yields on CDs oered by some

sample of banks. Data on yields oered on CDs by various

banks are compiled by bankrate.com, which reports averages

that are available on the Bloomberg service.

20

Chart 1 is a scatterplot that compares the yields on ve-

year bank CDs versus ve-year U.S. Treasuries. It shows a

CD-Treasury yield spread as of the last day of each month

from June 1998 through June 2011. Te CD-Treasury yield

spread equals the CD yield minus the Treasury yield. It

appears in the scatterplot as the distance from a given months

dot to the diagonal line. A normal, positive yield spreadone

that compensates for restricted marketabilitywill plot above

the diagonal. Te plot shows that yields on bank CDs tend

to track Treasury yields less closely when ve-year Treasury

yields are high, and shows that the CD-Treasury spread is

nearly always positive when the Treasury yield is below 5%.

Mainly, the CD-Treasury spread is just small. It averages

an implausible -0.053% per year in the 26 months when the

yield on 5-year Treasuries exceeded 5.0%, but still averages

only 0.49% in the other 131 months. My conclusion from

these data is that a typical CD-Treasury spread is no greater

than 0.5%. A CD-Treasury yield spread of 0.5% is almost

identical to the estimated yield spread of 0.49% between

Rule 144A bonds (the xed-income counterpart to restricted

stock) and otherwise-comparable free-trading corporate

bonds.

21

Restricted bonds are typically issued with registra-

tion rights. A yield spread of 0.5% could be included as an

illiquidity premium in an implementation of the Ibbotson

91 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance Volume 24 Number 1 A Morgan Stanley Publication Winter 2012

tory restriction is the sole cause of discounting. Considerable

research, some of it my own, suggests that regulatory restric-

tion is not even the primary cause of discounting. And

without this false assumption and its consequences, little of

the average discount can be tied to the restricted nature of

restricted stock.

Private-company status may merit a discount below

what core valuation methods (such as DCF analysis) would

indicate; indeed, it may even merit a double-digit discount.

But any merited large discount is not primarily a discount for

lack of marketability. Based on evidence from modern private

placements of common stock, the DLOM is not reliably

dierent from the DLOM on the riskless asset, or 2.5%.

robert comment is an Accredited Valuation Analyst who has taught

fnance at Johns Hopkins University, New York University, and the Univer-

sity of Rochester. He served as the SECs Deputy Chief Economist under

Chairman Arthur Levitt and has appeared as an expert witness in over 50

litigations. Dr. Comment can be reached at bobcomment@msn.com.

previous ndings. Moreover, my estimates based on private-

placement data are not statistically signicantly dierent from

the DLOM on the riskless asset of approximately 2.5%.

Valuations are a kind of expert opinion and, in the

Supreme Courts Daubert decision governing the admissi-

bility of expert opinion in court,

23

there is no grandfather

clause that permits continued reliance on methods that are

seasoned but unreliable. In Daubert, the Supreme Court

demoted general acceptance from being the sole requirement

for the admissibility of expert opinion, as it had been for

70 years (under the Frye rule),

24

to one of several items in a

non-exclusive list of indicia of the ultimate goal of reliability.

Moreover, the acceptability contemplated by the Supreme

Court is that within the relevant scientic community.

Daubert requires reliability and fealty to the scien-

tic method. In a follow-on decision in Kuhmo Tire,

25

the

Supreme Court told the many clinician critics of its Daubert

ruling, in eect, to get with the program. Yet, proponents

of double-digit DLOMs have overlooked scientic studies

of private-placement discounts and continued to rely on

evidence that depends on a false assumption: that the regula-

23. Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

24. Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923).

25. Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael, 526 U.S. 137 (1999).

Journal of Applied Corporate Finance (ISSN 1078-1196 [print], ISSN

1745-6622 [online]) is published quarterly, on behalf of Morgan Stanley by

Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., a Wiley Company, 111 River St., Hoboken,

NJ 07030-5774. Postmaster: Send all address changes to JOURNAL OF

APPLIED CORPORATE FINANCE Journal Customer Services, John Wiley &

Sons Inc., 350 Main St., Malden, MA 02148-5020.

Information for Subscribers Journal of Applied Corporate Finance is pub-

lished in four issues per year. Institutional subscription prices for 2012 are:

Print & Online: US$484 (US), US$580 (Rest of World), 375 (Europe),

299 (UK). Commercial subscription prices for 2012 are: Print & Online:

US$647 (US), US$772 (Rest of World), 500 (Europe), 394 (UK).

Individual subscription prices for 2011 are: Print & Online: US$109 (US),

61 (Rest of World), 91 (Europe), 61 (UK). Student subscription pric-

es for 2012 are: Print & Online: US$37 (US), 21 (Rest of World), 32

(Europe), 21 (UK).

Prices are exclusive of tax. Australian GST, Canadian GST and European

VAT will be applied at the appropriate rates. For more information on cur-

rent tax rates, please go to www.wileyonlinelibrary.com/tax-vat. The institu-

tional price includes online access to the current and all online back fles to

January 1st 2008, where available. For other pricing options, including

access information and terms and conditions, please visit www.wileyonlineli-

brary.com/access

Journal Customer Services: For ordering information, claims and any inquiry

concerning your journal subscription please go to www.wileycustomerhelp.

com/ask or contact your nearest offce.

Americas: Email: cs-journals@wiley.com; Tel: +1 781 388 8598 or

+1 800 835 6770 (toll free in the USA & Canada).

Europe, Middle East and Africa: Email: cs-journals@wiley.com;

Tel: +44 (0) 1865 778315.

Asia Pacifc: Email: cs-journals@wiley.com; Tel: +65 6511 8000.

Japan: For Japanese speaking support, Email: cs-japan@wiley.com;

Tel: +65 6511 8010 or Tel (toll-free): 005 316 50 480.

Visit our Online Customer Get-Help available in 6 languages at

www.wileycustomerhelp.com

Production Editor: Joshua Gannon (email:jacf@wiley.com).

Delivery Terms and Legal Title Where the subscription price includes print

issues and delivery is to the recipients address, delivery terms are Delivered

Duty Unpaid (DDU); the recipient is responsible for paying any import duty or

taxes. Title to all issues transfers FOB our shipping point, freight prepaid. We

will endeavour to fulfl claims for missing or damaged copies within six months

of publication, within our reasonable discretion and subject to availability.

Back Issues Single issues from current and recent volumes are available at

the current single issue price from cs-journals@wiley.com. Earlier issues may

be obtained from Periodicals Service Company, 11 Main Street, German-

town, NY 12526, USA. Tel: +1 518 537 4700, Fax: +1 518 537 5899,

Email: psc@periodicals.com

This journal is available online at Wiley Online Library. Visit www.wileyon-

linelibrary.com to search the articles and register for table of contents e-mail

alerts.

Access to this journal is available free online within institutions in the devel-

oping world through the AGORA initiative with the FAO, the HINARI initiative

with the WHO and the OARE initiative with UNEP. For information, visit

www.aginternetwork.org, www.healthinternetwork.org, www.healthinternet-

work.org, www.oarescience.org, www.oarescience.org

Wileys Corporate Citizenship initiative seeks to address the environmental,

social, economic, and ethical challenges faced in our business and which are

important to our diverse stakeholder groups. We have made a long-term com-

mitment to standardize and improve our efforts around the world to reduce

our carbon footprint. Follow our progress at www.wiley.com/go/citizenship

Abstracting and Indexing Services

The Journal is indexed by Accounting and Tax Index, Emerald Management

Reviews (Online Edition), Environmental Science and Pollution Management,

Risk Abstracts (Online Edition), and Banking Information Index.

Disclaimer The Publisher, Morgan Stanley, its affiliates, and the Editor

cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal. The views and opinions

expressed in this journal do not necessarily represent those of the

Publisher, Morgan Stanley, its affliates, and Editor, neither does the pub-

lication of advertisements constitute any endorsement by the Publisher,

Morgan Stanley, its affliates, and Editor of the products advertised. No person

should purchase or sell any security or asset in reliance on any information in

this journal.

Morgan Stanley is a full-service financial services company active in

the securities, investment management, and credit services businesses.

Morgan Stanley may have and may seek to have business relationships with

any person or company named in this journal.

Copyright 2012 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved. No part of this publi-

cation may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means

without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. Authoriza-

tion to photocopy items for internal and personal use is granted by the copy-

right holder for libraries and other users registered with their local Reproduc-

tion Rights Organization (RRO), e.g. Copyright Clearance Center (CCC), 222

Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA (www.copyright.com), provided

the appropriate fee is paid directly to the RRO. This consent does not extend

to other kinds of copying such as copying for general distribution, for advertis-

ing or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works or for resale.

Special requests should be addressed to: permissionsuk@wiley.com.

This journal is printed on acid-free paper.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lord Mansfield and The Law MerchantDocument19 pagesLord Mansfield and The Law MerchantjpkoningNo ratings yet

- Clower - 1967 - A Reconsideration of The Microfoundations of Monetary TheoryDocument8 pagesClower - 1967 - A Reconsideration of The Microfoundations of Monetary TheoryjpkoningNo ratings yet