Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Second Wave Erp Teaching

Uploaded by

Linda PertiwiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Second Wave Erp Teaching

Uploaded by

Linda PertiwiCopyright:

Available Formats

Second Wave ERP Education

Paul Hawking

Brendan McCarthy

Andrew Stein

School of Information Systems

Victoria University

Melbourne

Australia

Paul.Hawking@vu.edu.au

ABSTRACT

In the 1990s there was considerable growth in implementations of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Systems.

Companies expected these systems to support many of the day to day business transactions. The growth in ERP

implementations had a resultant impact on the demand for ERP skills. Many universities recognised this demand

and the potential of using ERP Systems software as a teaching tool, and endeavoured to incorporate ERP systems

into their curriculum; however most universities have struggled in this task. ERP systems have now evolved to

incorporate more strategic components and universities and ERP vendors are investigating ways in which

curriculumcan be developed to support these new solutions. This paper discusses the evolution of ERP systems

and university curriculum. It identifies how one university is addressing this problemand how this approach could

be adopted and expanded by other universities.

Keywords: Enterprise Resource Planning Systems, Application Hosting, ERP education

INTRODUCTION

Many universities have committed considerable

time and resources in modifying their curriculumto

incorporate Enterprise Resource Planning Systems

(ERP) (Hawking, Shackleton & Ramp, 2001;

Lederer-Antonucci, 1999; Watson and Schneider,

1999). For many universities it has been a struggle

even though ERP vendors have developed a number

of initiatives to facilitate curriculumdevelopment.

As companies ERP system usage has become more

strategic in nature, ERP curriculumneeds to evolve

to reflect and support this usage. Information

Systems curriculumin universities has undergone

rapid and continuous change in response to the

evolution of industry requirements. Over a period

of 40 years, the Information Systems (IS) discipline

has become an essential component in the

employment of information technology personnel in

business and government organisations. In recent

times there have been discussions by IS

professionals on how to best respond to

developments in the information and

communications technology (ICT) industry. The

industry now requires a broad range of skills that

support the development, implementation and

maintenance of e-business solutions. A recent

Australian report identified skill shortages in

security/risk management, enterprise resource

planning (ERP) systems, data warehousing and

customer relationship management (CRM) (ICT

Skills Snapshot, 2003). Over the same period there

has been a downturn in employment opportunities in

this the ICT industry (ICT Skills Snapshot, 2003).

Recent research indicates that many of the entry-

level positions graduates traditionally go into have

diminished due to the economic downturn and to

companies outsourcing positions offshore. This

paper discusses the evolution of ERP education and

the issues it now faces. It provides an example of

how one university is addressing the second wave

of ERP education and the challenges that educators

face in preparing students for rapidly developing

software environments.

ERP SKILLS & CURRICULUM

APPROACHES

The shortage of ERP related skills is not a recent

phenomenon. A survey by Hewitt Associates

(1999) found that people with ERP skills were in

short supply, and consequently in high demand

experiencing rapid changes in their market value. In

Australia, an IT Skills Shortage study (ICT Skills

Snapshot, 2003) commissioned by the Government,

found skill shortages in enterprise wide systems, and

more specifically SAP R/3 and PeopleSoft

implementation and administration. The

Department of Immigration and Multicultural

Affairs in their Migration Occupations in Demand

List (MODL 2000) identified information

technology specialists with SAP R/3 skills as people

who would be encouraged to migrate to Australia.

In accordance with this demand many universities

identified the value of incorporating ERP systems

into their curriculum. ERP systems can be used to

reinforce many of the concepts covered in the

business discipline (Becerra-Fernandez et al, 2000;

Hawking et al, 2001). The ERP vendors argue that

their products incorporate worlds best practice

for many of the business processes they support,

making theman ideal teaching tool (Hawking, 1999;

Watson and Schneider, 1999), while at the same

time increasing the employment prospects of

graduates. Universities also realised the importance

of providing students with hands on experience

with particular ERP systems and formed strategic

alliances with ERP systemvendors to gain access to

these systems. The ERP vendor benefited from

these alliances by increasing the supply of skilled

graduates that can support their product thereby

enhancing its marketability and lowering the cost of

implementation.

Universities who decided to introduce ERP related

curriculumwere faced with a number of barriers.

For many universities getting access to an ERP

system to provide hands on learning environment

was not a major issue, however, the lack of ERP

related skills of academic staff and accordingly the

development of appropriate curriculummaterial was

and still is a major hurdle. SAP, the leading ERP

vendor has established the largest ERP university

alliance with more than 400 universities worldwide

accessing their ERP system (SAP R/3). They have

introduced a number of initiatives to facilitate the

incorporation of their system into university

curriculum. Initially when universities joined the

alliance they were provided with free training for

academic staff and access to training materials. The

amount of training made available and the

restrictions how the training materials could be used

varied from country to country and to a certain

extent fromuniversity to university within the same

country.

The transporting of SAP training materials into a

university environment, as many universities

attempted to do, was not a simple process. The

training materials were often version dependent and

utilized preconfigured data that was not readily

available in the universities systems. The SAP

training exercises were often just snapshots to

reinforce particular features of the system and

therefore were not comprehensive exercises

illustrating end-to-end processes relevant in ERP

education. For example, staff soon came across the

problems associated with opening and closing

posting periods that often prevented certain

transactions frombeing completed in the system.

This concept is rarely covered in training courses

even though it impacts on many processes.

The curriculumdeveloped by universities could be

classified into one of four different curriculum

approaches or a fifth, being a hybrid of the four:

1. ERP training;

2. ERP via Business Processes;

3. Information Systems Approach;

4. ERP concepts; and

5. The Hybrid.

The first, which is least preferred by academic

institutions, focuses on the instruction or training in

a particular ERP system. There has been increasing

pressure from both students and industry for

universities to offer subjects based on this type of

curriculum direction. In the case of SAP, the

Alliance specifies that specific training of SAP R/3

is the domain of SAP.

The second curriculumapproach retains the focus

on business processes but uses the ERP systemto

assist in the presentation of information and skills

development. Most ERP systemvendors argue that

their particular system incorporates best business

practice and, as a consequence, students use the

system to enhance their understanding of the

processes and their interrelationships, especially in

the area of supply chain management.

The third approach is the use of ERP systems to

teach and reinforce information system concepts.

ERP systems provide students with the opportunity

to study a real world example of a business

information system, often incorporating state of the

art technology.

The final curriculumdirection is to teach about ERP

systems and concepts. This is different fromthe

first curriculumapproach outlined above in that it

deals with general ERP issues and the implications

for an organisation for implementing this type of

information systemrather than training in a specific

system.

No matter which model universities adopted, the

acquired knowledge of academics involved in ERP

education is difficult to encapsulate and therefore

the curriculumis often dependent on relatively few

staff. Usually there is a core of academics who have

spent many hours working on the system; once these

staff leave a university or change direction then the

curriculumusually flounders. This has been evident

in Australia where from the original thirteen

universities involved in the SAP alliance only seven

remain. Some universities were able to develop and

retain their ERP skills while others struggled. SAP

(Americas) established the SAP CurriculumAwards

and CurriculumCongress in an attempt to facilitate

the problems many universities were facing. The

Congress was designed to bring together academics

involved in ERP education where they could share

their experiences and to be made aware of new

product developments. The awards identified and

financially rewarded exemplary programs, however

there was limited sharing of the curriculum. Some

universities considered the curriculum their

competitive edge and intellectual property or

conversely it was not documented to a level that

made it accessible to others. Recently SAP has

established their education and research portal,

Innovation Watch

1

, to facilitate collaboration

between universities. The site includes a range of

plug and play curriculummaterials; however not

all university alliance members have access to it or

are even aware of it. The quality of the curriculum

varies enormously and some is far fromplug and

play.

Due to escalating demands associated with

administering new versions SAP R/3 and to

facilitate the entrance of new universities into the

alliance, SAP established a number of application

hosting centres around the world in universities with

established ERP curriculumofferings. The hosting

model varied from country to country with some

only providing access to systems rather than

curriculum. However SAP considered that the

increasing support universities required could be

provided by the hosting centres and therefore lessen

the burden on SAP.

SECOND WAVE ERP

A question that must be asked relates to the

relevance of current ERP curriculum to industry

requirements. The SAP University Alliance,

established in the mid nineties, followed closely the

growth in ERP usage in industry. Originally ERP

systems were adopted as complex transaction

processing systems responsible for handling

millions of transactions fromthe various business

areas within a company. Their strength came from

their integrative nature including the standardised

definition of master data items across the system

and the efficient flow of data between its various

components. The definitions and flow were based

on best business practice and thus often provided

a catalyst for organisational change and

standardisation within an organisation. Additionally

for many companies the implementation of this type

of systemwas a technological solution to the Y2K

issue (Deloitte, 1999; Davenport et al 2002).

To facilitate an effective implementation within a

company, business process engineering was initiated

for the purpose of gap analysis. This was

designed to determine what changes were needed in

the company or in the ERP system. Underestimating

the impact the system would have on their

organization, companies initially struggled with

their ERP implementation due to lack of skilled

resources and inexperience with projects of this

scope. For some companies these barriers became

insurmountable (Calegero, 2000). For many

companies the urgency to achieve Y2K deadlines

and the lack of understanding of the complexity of

these types of implementations resulted in a failure

to optimize their business processes during

implementation (Davenport et al 2002). Although

1

http://services.sap.com/iw

companies solved their Y2K issues the majority of

companies did not achieve the additional benefits

they had expected fromtheir ERP system(Deloitte,

1999; Davenport et al 2002). For some companies

the additional benefits only became obvious once

they had been using their ERP system for a period

of time and became aware of its potential.

This lack of benefit realization has resulted in

companies revisiting their ERP implementation in

an attempt to leverage their investment by attaining

the purported benefits. A study by Davenport et al

(2002) identified the top ten benefits that can be

gained froman ERP implementation (Table 1).

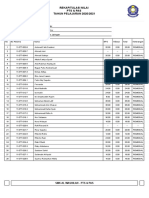

Table 1. Top Ten ERP Benefits

Benefit

Improved management decision making

Improved financial management

Improved customer service and retention

Ease of expansion/growth and increased

flexibility

Faster, more accurate transactions

Headcount reduction

Cycle time reduction

Improved inventory/asset management

Fewer physical resources/better logistics

Increased revenue

A Computer Science Consultants (CSC) study

(2001), which surveyed 1009 IS managers from

around the world, identified optimising enterprise

wide systems as their main priority. In the

landmark Deloittes study (1999), 49% of the

sample considered that an ERP implementation is a

continuous process, as they expect to continually

find value propositions fromtheir system. This is a

reasonable expectation as companies attempt to

realise previously unattained benefits and

additionally, as companies evolve, their ERP system

must also evolve to support new business processes

and information needs. Davenport et al (2002)

believes that the potential of ERP systems can be

classified under three groups; Integrate, Optimise,

and Informate. Integrate is where a company is able

to integrate their data and processes internally and

externally with customers and suppliers. While

Optimise benefits include the standardization of

business processes incorporating best business

practice and Informate is the ability to provide

context rich information to support effective

decision making.

This evolutionary nature of ERP usage is reinforced

by CAP Gemini, Ernst and Young (2002) who

believe that a companys ERP systemcan formthe

foundation for increased collaboration between

business partners and assist in a company becoming

an Adaptive Enterprise(Figure 1).

Figure 1 CAP Gemini et al (2002) Adaptive ERP

This type of enterprise and its business processes

can quickly adapt to both internal and external

factors. Accordingly the emphasis on increased

integration and collaboration both internally and

externally has resulted in ERP vendors releasing a

range of products to support these goals. CAP

Gemini et al (2002) produced an Adaptive ERP

Index to assist companies to determine their

progress towards an Adaptive Enterprise. The

index was made up of four components:

Improved applications functionality,

Improved use of current applications to

increase collaboration with business

partners,

Improved applications integration, and

Improved use of current applications to

increase internal process effectiveness.

The notion of differing evolutionary maturity stages

of ERP implementation is espoused in the work by

Nolan and Norton (2000). They argued that when

evaluating costs of an ERP implementation, the

companys previous experience with ERP systems

should be considered. Their maturity classifications

were:

Beginning implemented SAP in the past

12 months;

Consolidating implemented SAP

between 1 and 3 years; and

Mature implemented SAP for more than

3 years.

Accordingly ERP vendors have extended the

functionality of their ERP systems beyond

transaction processing. The release of mySAP.com

highlighted this evolution with SAP R/3 being only

one component of this solution. MySAP.comwas a

consolidation of many of SAP existing products

under one umbrella. It was based on extending the

functionality and reach of the ERP system. It

provided the ERP systemwith an external focus in

terms of business partners and customers. The

components of mySAP.com included; Business

Warehouse (BW), Advanced Planner Optimiser

(APO), Strategic Enterprise Management

(SEM), Knowledge Management (KM),

Customer Relationship Management

(CRM). SAP has since changed the

name and shape of the umbrella to

MySAP Business Suite, but still offers

similar solutions with the addition of

portal technology and an integration

framework (NetWeaver).

SECOND WAVE ERP EDUCATION

The Managing Director of SAP

Australasia (Bennett 2000) identified a

number of factors that are important to

the implementation of effective ERP

curriculum into the future. The

curriculum would move from

transactional to strategic and focus on

mySAP.comcomponents. It would focus on the

role the ERP system has in e-business and would

closely be aligned to technology and market trends.

Davenport et al (2002) believes for a company to

achieve second wave benefits that there are three

essential factors. Firstly, the organisation must have

had several years experience with enterprise wide

systems; secondly, the systems need to be used

extensively throughout the organization and thirdly,

significant resources should be allocated to future

implementations.

These same prerequisites are just as applicable to

ERP curriculumdevelopment. This is a dilemma

for SAP and other ERP vendors if they want

students to develop more strategic ERP skills, as

many universities are still struggling at the

operational level. To incorporate these products into

curriculum requires a solid understanding of the

underlying ERP system in addition to the second

wave solutions as well as providing the necessary

technological infrastructure to support the solutions

(Rosemann et al, 2000). It was envisaged by SAP

that Application Hosting Centres could provide the

necessary infrastructure. However the complexity of

these new wave products makes it difficult for the

hosting centres to implement all the solutions and

make themavailable to their client universities.

POSSIBLE SOLUTION

Victoria University has been a member of the SAP

University Alliance since 1998. It adopted a faculty

approach to the introduction of ERP curriculumas

the solution was seen as a tool that could reinforce

many of the business and information systems

concepts taught across the faculty. The university

now has approximately twenty-five subjects at both

the undergraduate and postgraduate levels that

incorporate SAP and related products. These

subjects formpart of master degree programthat is

taught in Australia, Singapore and China. Even

though the university has well-established

curriculum, it also faced with the dilemma of how it

could take advantage of the educational potential of

SAPs second wave components. It was felt that

existing staff were stretched to the limit, and time

and effort to develop this new curriculumwould be

insurmountable. As a pilot program in 2002, the

university identified academics from around the

world that had the skills, curriculum, and access to

systems to teach the specialist solutions. An

academic was invited to teach their curriculumat

Victoria University through a concentrated mode

(one or two weeks). This also relied on Victoria

University students accessing the visiting lecturers

ERP system and any add on solutions in their

university via the Internet.

The pilot had a number of obvious benefits. Firstly

the visiting academic provided access to the

curriculum skills and system. Secondly resident

staff received professional development as they

assisted in the class. Thirdly students gained access

to education they would not readily receive. Finally

the pilot provided the foundation for future

collaboration between the participating universities.

Due to the success of the pilot in the ERP program,

three subjects were offered via this method in 2003.

The collaboration has resulted in Victoria University

staff being invited to other universities to teach

curriculum that was unavailable in these

universities.

This initiative could form the basis of similar

specialist programs around the world to address

second wave education. SAP would identify key

personnel around the world and commission themto

develop comprehensive curriculum. SAP would

establish a curriculum review committee which

would establish guidelines for the developed

curriculummaterials including templates and would

also review submitted materials. The curriculum

developed would include both theoretical and

practical components as well as support

documentation for common problems. These

teaching materials would be based on versions of

the solutions readily available from a particular

hosting centre or specialist university. Initially

universities could employee the specialist academic

to conduct a course and or provide professional

development to the local staff. The following

semester the local staff could conduct the class with

the supplied course materials and remotely

supported by the specialist academic. Once the

local staff became proficient in the solution they

could contribute to the curriculumdevelopment and

support. As the skills of academics in second

wave products developed they in turn could

develop new curriculum or extend the original

curriculumand in turn support other universities.

This would relieve the demand on the specialist

academics.

Hosting centres and specialist universities would

need to become solution specific and thus alliance

universities would access a network of universities

for solution provision. This would alleviate the

pressure on hosting centres to have the necessary

infrastructure and expertise to offer a

comprehensive range of solutions. This also enables

staff in these universities to specialize in a particular

solution.

Even though the visiting academic initiative has

potential to address the problems with second

wave education there are a number of prerequisites

for its success. Firstly the specialist academics need

to be carefully selected and reimbursed for the

curriculum development, visiting teaching and

ongoing support. Secondly a template and

guidelines for the curriculumneeds to be developed

and adhered to by the specialist academics to ensure

quality curriculum and true plug and play and

consistency. Thirdly hosting centres would need to

develop flexible service level agreements and

affordable access fees to enable universities to

easily and quickly to access their solution.

If this solution was implemented then research

would need to be undertaken as to its success. This

would include an evaluation of skills covered and

their relevance to industry. Research would also

need to identify any other barriers which may be

hindering the incorporation of second wave

products into the curriculum.

CONCLUSION

Universities who have worked very hard to develop

ERP curriculumare now faced with the dilemma of

evolving their curriculumto reflect the evolution of

ERP systems and industry requirements. The

evolution of ERP systems froman operational to a

more strategic focus requires a different skill set to

support this transition. The visiting lecturer delivery

method could be further extended whereby a

directory of specialist academics could be

established by SAP and distributed to alliance

members. These academics could be provided with

additional support from SAP to assist them to

further develop their curriculumwith the goal of

making it portable to other universities. Universities

and ERP vendors need to develop strategies on how

to best address the new skills deficit. For this to

occur there will need to be more collaboration than

exists at present.

REFERENCES

Becerra-Fernandez, I., Murphy, K. E. and Simon, S.

J . (2000), Enterprise resource planning:

integrating ERP in the business school

curriculum Communications of the ACM,

Volume 43, No. 4, April, Pages 39 41.

Bennett, C. (2000), Welcoming Address,

Application Hosting Centre, Sapphire

Conference, Singapore.

CAP Gemini, Ernst and Young, (2002), Adaptive

ERP, located at

www.cgey.com/solutions/erpeea/media/Adapti

veERPPOV.pdf accessed J anuary 2003.

Computer Science Consultants, (2001). Critical

Issues of Information Systems Management,

Located at

http://www.csc.com/aboutus/uploads/CI_Repor

t.pdf accessed November 2002.

Davenport, T., Harris, J . and Cantrell, S. (2002),

The Return of Enterprise Solutions, Accenture.

Deloitte Consulting., (1999), ERPs second wave,

Deloitte Consulting.

Deloitte, Touche, and Tohmatsu, (1999), Future

Demand for IT&T Skills in Australia 1999-

2004, IT&T Skills Workforce, A Report

Developed for the Australian Government, as

reported in www.noie.com.au , accessed May

1999.

Hawking, P. (1999) The Teaching Of Enterprise

Resource Planning Systems (Sap R/3) In

Australian Universities in Proceedings of 9th

Pan Pacific Conference, 31 May-2 J une, Fiji.

Hawking, P., Shackleton, P. and Ramp, A., (2001),

IS 97 Model Curriculumand Enterprise

Resource Planning Systems Business Process

Management J ournal Vol. 7, No.3.

Hewitt Associates, (1999) Hot Technology Study:

Scarcity of IT Professionals Means Big Pay

Raises, retrieved May 2000 fromthe World

Wide Web

http://www.hewitt.com/compsurveys.

ICT Skills Snapshot, (2003), The State of ICT

Skills in Victoria, Department of

Infrastructure, J une 2003.

Lederer-Antonucci Y., (1999), Enabling the

business school curriculumwith ERP software

experiences of the SAP University Alliance,

Proceedings of the IBSCA99, Atlanta.

MODL, (2000), Migration to Australia - Skilled

Migration, Migration Occupations in Demand

List, retrieved May 2001 fromthe World Wide

Web

http://www.immi.gov.au/allforms/modl.htm.

Nolan and Norton Institute, (2000), SAP

Benchmarking Report 2000, KPMG

Melbourne.

Rosemann, M., Scott, J ., and Watson, E., (2000),

Collaborative ERP Education: Experiences

froma First Pilot, Proceedings of the 6th

Americas Conference on Information Systems

(AMCIS.00), H. M. Chung (ed.), Long Beach,

CA.

Watson, E. and H. Schneider, (1999), Using ERP

Systems in Education. Communication of the

Association for Information Systems, 1(9).

Author Biographies

Paul Hawking is a senior

lecturer in the School of

Information Systems at

Victoria University,

Melbourne, Australia. He is

the SAP Academic Program

Director for the Faculty of

Business and Law and is

responsible for the facilitation

of ERP education across the

university. He is also

coordinator of the universitys ERP Research

Group and published a number of papers in this

area. Paul has been involved in education delivery

and curriculumdevelopment for the past twenty

years and has co-authored a series of computer

texts. He is past Chairperson of the Australian SAP

User Group.

Paul is also a Certified SAP Consultant in Business

Warehouse.

Brendan McCarthy is a

lecturer in the School of In-

formation Systems at Victoria

University. He is the

coordinator of the Masters in

Enterprise Resource Planning

Systems program. He has been

involved in education delivery

and curriculumdevelopment

for the past twenty-five years

and has co-authored of a series

of computer texts. His area of research includes e-

learning and ERP systems.

Andrew Stein is a lecturer in

the School of information

Systems in the Faculty of

Business and Law at Victoria

University. He has contributed

to numerous international

journals including:

International J ournal of

Management, J ournal of

Information Management,

J ournal of ERP Implementation and Management,

J ournal of Contemporary Business Issues and the

Asia Pacific J ournal of Marketing and Logistics and

contributed to HICSS conferences. He is a member

of the ERP Research Group at Victoria University.

You might also like

- Aydin & Tasci (2005)Document14 pagesAydin & Tasci (2005)brigiett4No ratings yet

- SPAIN Remesal2011 PDFDocument11 pagesSPAIN Remesal2011 PDFMokhtarBariNo ratings yet

- Contextual Factors That Sustain Innovative Pedagogical Practice Using Technology An International StudyDocument17 pagesContextual Factors That Sustain Innovative Pedagogical Practice Using Technology An International StudyLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Thurlow 1989Document23 pagesThurlow 1989Linda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Feedback in Language AssessmentDocument32 pagesDiagnostic Feedback in Language AssessmentLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Baird 2013Document4 pagesBaird 2013Linda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Knoch 2009Document30 pagesKnoch 2009Linda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Peterson 2008Document13 pagesPeterson 2008Linda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- The Multicollinearity Between Youth Sport Environment Questionnaire and Team Assessment Diagnostic Measurement in Sport SettingsDocument10 pagesThe Multicollinearity Between Youth Sport Environment Questionnaire and Team Assessment Diagnostic Measurement in Sport SettingsLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Analisis Kebijakan PPDB Zonasi Terhadap Prilaku Siswa SMP D YogyakartaDocument10 pagesAnalisis Kebijakan PPDB Zonasi Terhadap Prilaku Siswa SMP D YogyakartaLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Online Diagnostic Assessment in Support of Personalized Teaching and Learning: The Edia SystemDocument14 pagesOnline Diagnostic Assessment in Support of Personalized Teaching and Learning: The Edia SystemLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Brown 2011Document20 pagesBrown 2011Linda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Eisenberg, Rachel A. (2015) PDFDocument237 pagesEisenberg, Rachel A. (2015) PDFLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Social effects of peer assessmentDocument35 pagesSocial effects of peer assessmentLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- 05-116-Hyejin ParkDocument23 pages05-116-Hyejin ParkLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- 01-Michele L. Stites and Christopher R. Rakes (2018) - Teacher Perceptions Program InclusiveDocument20 pages01-Michele L. Stites and Christopher R. Rakes (2018) - Teacher Perceptions Program InclusiveLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- BrownDocument19 pagesBrownLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- 04-Romero-Tena2020 - Digital CompetencesDocument17 pages04-Romero-Tena2020 - Digital CompetencesLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- 02 - Jale Aldemir & Hengameh Kermani (2017) - Integrated STEM CurriculumDocument14 pages02 - Jale Aldemir & Hengameh Kermani (2017) - Integrated STEM CurriculumLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- 07-International Journal of InstructionDocument20 pages07-International Journal of InstructionLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Rekapitulasi Nilai Pts & Pas TAHUN PELAJARAN 2020/2021Document2 pagesRekapitulasi Nilai Pts & Pas TAHUN PELAJARAN 2020/2021Linda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Perkalian 1-20Document3 pagesPerkalian 1-20Linda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Islam and BusinessDocument15 pagesIslam and BusinessShirat MohsinNo ratings yet

- Financial Performance Impacts of Corporate EntreprDocument12 pagesFinancial Performance Impacts of Corporate EntreprLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Perkalian 1-20Document3 pagesPerkalian 1-20Linda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Information & Management: Ching-Wen ChenDocument8 pagesInformation & Management: Ching-Wen ChenLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Kolaborasi Metode Ceramah Diskusi Dan LatihanDocument8 pagesKolaborasi Metode Ceramah Diskusi Dan LatihanLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Teori Pengembangan Ekonomi PDFDocument178 pagesTeori Pengembangan Ekonomi PDFLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Hassan PDFDocument8 pagesHassan PDFritusinghtoor4291No ratings yet

- Aydin & Tasci (2005)Document14 pagesAydin & Tasci (2005)brigiett4No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Outside MicrometerDocument13 pagesOutside MicrometerSaravana PandiyanNo ratings yet

- Acute Renal Failure - PPT 1Document36 pagesAcute Renal Failure - PPT 1Jay PaulNo ratings yet

- PSED5112 Assignment 1Document9 pagesPSED5112 Assignment 1Aqeelah KayserNo ratings yet

- Fairfield Institute of Management and Technology: Discuss The Nature, Scope and Objectives of PlanningDocument7 pagesFairfield Institute of Management and Technology: Discuss The Nature, Scope and Objectives of PlanningAYUSHNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes in Phil History and RizalDocument11 pagesLecture Notes in Phil History and RizalSheen Mae OlidelesNo ratings yet

- Digested Labor Relations CasesDocument4 pagesDigested Labor Relations CasesRam BeeNo ratings yet

- Applied Neuropsychology: ChildDocument8 pagesApplied Neuropsychology: Childarif3449No ratings yet

- Optical Measurement Techniques and InterferometryDocument21 pagesOptical Measurement Techniques and InterferometryManmit SalunkeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 17Document6 pagesChapter 17Laramy Lacy MontgomeryNo ratings yet

- 01549386Document6 pages01549386Pallavi Kr K RNo ratings yet

- 10 Common Job Interview Questions and How To Answer ThemDocument9 pages10 Common Job Interview Questions and How To Answer ThemBala NNo ratings yet

- Gut and Psychology SyndromeDocument12 pagesGut and Psychology SyndromeJhanan NaimeNo ratings yet

- (Sabeel) Divine Science - Part One Retreat NotesDocument43 pages(Sabeel) Divine Science - Part One Retreat Notesstarofknowledgecom100% (1)

- OTC 3965 Hybrid Time-Frequency Domain Fatigue Analysis For Deepwater PlatformsDocument18 pagesOTC 3965 Hybrid Time-Frequency Domain Fatigue Analysis For Deepwater PlatformscmkohNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Deep Breathing Terhadap Kecemasan Pra OperasiDocument14 pagesPengaruh Deep Breathing Terhadap Kecemasan Pra OperasiAch ThungNo ratings yet

- External Review of Riverside County Department of Public Social Services, Child Services DivisionDocument7 pagesExternal Review of Riverside County Department of Public Social Services, Child Services DivisionThe Press-Enterprise / pressenterprise.comNo ratings yet

- TH THDocument5 pagesTH THAngel MaghuyopNo ratings yet

- EvidenceDocument3 pagesEvidenceAdv Nikita SahaNo ratings yet

- Best Chart PatternsDocument17 pagesBest Chart PatternsrenkoNo ratings yet

- I Want A Wife by Judy BradyDocument3 pagesI Want A Wife by Judy BradyKimberley Sicat BautistaNo ratings yet

- Free Publications by DevelopmentDocument1 pageFree Publications by DevelopmentaeoiuNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-342498870No ratings yet

- Talaan NG Ispisipikasyon Ikalawang Markahang Pagsusulit Sa Musika 6 (Second Quarterly Test in Music 6) S.Y.2018-2019Document5 pagesTalaan NG Ispisipikasyon Ikalawang Markahang Pagsusulit Sa Musika 6 (Second Quarterly Test in Music 6) S.Y.2018-2019Maicah Alcantara MarquezNo ratings yet

- Warren Buffet Powerpoint PresentationDocument7 pagesWarren Buffet Powerpoint Presentationzydeco.14100% (2)

- Deep Vein ThrombosisDocument11 pagesDeep Vein ThrombosisTushar GhuleNo ratings yet

- Unidad 2 2do Año LagunillaDocument7 pagesUnidad 2 2do Año LagunillaAbdoChamméNo ratings yet

- EAPP Activity SheetDocument11 pagesEAPP Activity SheetMary Joy Lucob Tangbawan0% (1)

- G.R. No. 114337 September 29, 1995 NITTO ENTERPRISES, Petitioner, National Labor Relations Commission and Roberto Capili, RespondentsDocument24 pagesG.R. No. 114337 September 29, 1995 NITTO ENTERPRISES, Petitioner, National Labor Relations Commission and Roberto Capili, RespondentsLuis de leonNo ratings yet

- CISD Group Stress DebriefingDocument18 pagesCISD Group Stress DebriefingRimRose LamisNo ratings yet

- Noahides01 PDFDocument146 pagesNoahides01 PDFxfhjkgjhk wwdfbfsgfdhNo ratings yet