Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mamphela Aletta Ramphele's Speech

Uploaded by

The New Vision0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3K views17 pagesMamphela Aletta Ramphele's Speech

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMamphela Aletta Ramphele's Speech

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3K views17 pagesMamphela Aletta Ramphele's Speech

Uploaded by

The New VisionMamphela Aletta Ramphele's Speech

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 17

1

CREATING A VIBRANT AND FAIR SOCIETY: TRANSPARENCY

AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Introduction

I am not sure that I am the right person to speak to you

about this topic today. As you know I come fresh from the

frontline of party politics. I was prevailed upon by my fellow

citizens to enter party politics and become part of the change

in its ethos. A few months later my fellow citizens said

resoundingly that they were not ready for that change in the

nature of the business of politics! I am grateful for the

lessons learnt from this failed bid about servant leadership.

Servant leadership is about listening even when the message

is uncomfortable.

It is my considered view that Africa still has to reflect deeper

about the theme of servant leadership as an essential

building block for creating Vibrant and Fair Societies. Leaders

in public service are agents of citizens, servants of the

people. The model of servant leadership underpinned social

relationships in African traditional society. This is captured

most aptly in the saying that: Kgosi ke kgosi ka sechaba (the

king is only a king with the consent of the nation). Creating

vibrant fair societies requires, amongst others, that we pay

greater attention to the theme of servant leadership.

There is an inherent contradiction in Africa - our continent.

We are a continent that articulates most elegantly the

2

concept of Ubuntu - our belief in the notion of a common

humanity as an essential pillar of being human. Ubuntu

captures the essential truth that our humanity is affirmed by

our connectedness to one another. This philosophical

approach confronts us with the existential reality that we

are human because others are. Yet we are a continent that

has struggled to date to create vibrant fair societies in which

the human rights of all are respected and the talents of all

citizens are harnessed.

There is a growing body of literature that confirms what our

wise hunter gatherer ancestors understood millennia ago

that too great a degree of inequality makes human

community impossible. In The Spirit Level

1

, Richard

Wilkinson and Kate Pickett conclude, after a wide review of

studies across the globe, that the health of our democracies,

our societies and their people, is truly dependent on greater

equality.

My task today is to explore with you how we can create

vibrant and fair societies through more transparent

accountable governance systems. This is a tall order. It is

one thing to know what needs to be done, but an entirely

different matter to have the political will and capacity to do

what is right. Our continent is littered with examples of lofty

ideals that rarely translate into successful outcomes. Our

1

The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone, Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, Penguin Books,

2010, p298

3

leaders from liberation struggles, post-colonial governments,

New Partnership for Africas Development and more recent

promises at the African Union meetings, have yet to follow

through with transparent accountable governance programs

that change the lives of the majority of Africas citizens.

In this talk I would like to:

1) Examine why Africa continues to live with the

contradictions between proud philosophical

pronouncements and lived reality of the majority of citizens.

2) Explore how Africa can Build Vibrant Fair systems of

governance?

3) Propose approaches to promote greater Transparency and

Accountability in governance

Why the Contradictions between Ubuntu and Dominance

Politics?

It is my humble view that Africa has yet to acknowledge the

extent of the impact of pre-colonial and colonial extractive

economic and political institutions on the political culture

that informed the post-colonial nature of the state and its

institutions. In Why Nations Fail Daron Acemoglu and James

Robinson conclude that Nations fail today because

extractive economic institutions do not create incentives

needed for people to save, invest and innovate.

2

2

Why Nations Fail, D. Acemoglu & J. Robinson, Random House, 2012 p372

4

The authors detailed comparative study of the evolution of

successful and failed nations across the globe, provides

compelling evidence of the reasons for the demise of

empires and the success of nations, that opt for inclusive

economic and political institutions. In Africa Botswana is a

shining example of successful sustainable development. It

compares favourably to the failures of Zimbabwe and Sierra

Leone despite, the opportunities both countries had to use

the attainment of independence to build strong inclusive

political and economic systems.

Botswana from pre-colonial days opted for inclusive

institutions under Seretse Khamas grandfather King Khama

111. He negotiated with Britain to make Bechuanaland a

protectorate, thus shielding it from extractive colonialism of

Cecil John Rhodes. Seretse Khama, as the first President, set

the foundations of a Botswana with one language, Setswana,

centralized the use of natural resources to benefit all citizens.

Botswanas leaders understood that: The logic of virtuous

cycles stems partly from the fact that inclusive institutions are

based on constraints on the exercise of power and on the

pluralistic distribution of political power in society, enshrined

in the rule of law. The ability of a subset to impose its will on

others without any constraints, even if those others are

ordinary citizens threatens this very balance.

3

3

Why Nations Fail, p308

5

But why did Botswana opt for the virtuous cycle of inclusive

economic and political institutions, whereas Zimbabwe

didnt? Why did South Korea go a different route to that of

North Korea? Why did South Africa falter in its

transformation towards more inclusive economic and

political institutions after a promising post-apartheid start?

Studies including the Acemogul and Robinson one quoted

above point to A confluence of factors, in particular a critical

juncture coupled with a coalition of those pushing for reform

or other propitious existing institutions, is often necessary for

a nation to make strides towards more inclusive institutions.

In addition some luck is key, because history always unfolds in

a contingent way.

4

The highly unequal colonial/apartheid societies we inherited

at the moment of our countries liberation infected us with

the affluenza virus,

5

a set of values which increase our

vulnerability to emotional distress. This distress arises from

our fear of being left behind in the race for power and

affluence. We tend to place a high value on acquiring money

and possessions, looking good in the eyes of others and

wanting to be famous. The tension between the idealism of

post-colonial transformation of our societies based on our

shared Ubuntu value system and the afflictions of the

affluenza virus is often resolved in favour of maintaining

our place on the ladder of social status in our highly unequal

societies.

4

Ibid, p427

5

Ibid, p69 quote from Oliver James, a psychologist and journalist

6

Like any other affliction, one cannot get help without

acknowledging that one needs such help. The denial of the

psycho-social scars inflicted by living in highly unequal

societies undermines our ability to create vibrant fair

societies. We tend to be over-sensitive to criticism of non-

transparent and unaccountable governance in our countries

at international forums even where the facts speak for

themselves. We defend the indefensible in our midst in the

name of African solidarity. But is this solidarity for the

benefit of the majority of citizens? Or is solidarity amongst

African leaders a protective shield behind which they hide

their poor performance to the detriment of ordinary citizens

of their countries?

The African Union (AU) has failed to model an inclusive

political institutional framework to support the emergence of

the virtuous cycles Africa so desperately needs to build

successful nations. The AU has recently adopted the Protocol

on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African

Court of Justice and Human Rights. This Protocol grants

immunity to prosecution for heads of state and public

officials. Article 46A of the Protocol states that: No charges

shall be commenced or continued before the court against

any serving African Union head of state or government, or

anybody acting or entitled to act in such capacity, or other

senior state officials based on their functions, during their

tenure of office. This is clearly intended to undermine the

7

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) which

upholds the principle of equality before the law. The AU in

one fell swoop has created an incentive for those violating

human rights to stay in office in perpetuity. How can this

build a vibrant and fair continent?

My own country, South Africa, is still burdened by the scars

of apartheids legacy of exclusive economic and political

institutions. The ANC as the governing party (or ruling party

as they style themselves), has failed to leverage the promise

of fundamental transformation based on our progressive

Constitution to build inclusive economic and political

institutions. The ANC is increasingly modelling itself on the

apartheid government ethos it replaced. They are creating

ever growing networks of in- and out-groups.

The systematic undermining of institutions created under

Chapter 9 of our Constitution that are intended to constrain

the power of those in public office and to promote the rule of

law, is another example of the desire to veer further into an

extractive political economy model. Our limited progress in

providing quality public services, especially health care,

human settlements, as well as education and training,

undermines our ability to promote human development and

an empowered citizenry. Extractive economic and political

institutions inherited from the apartheid system and

perpetuated to date, constrain our ability to take advantage

8

of technological and innovation opportunities to grow our

economy into a vibrant equitable and prosperous one.

The overtly brutal racist past has also left us with a significant

majority of black citizens with an inferiority complex. This

undermines their capacity to demand better accountability

from public servants and political leaders. This inferiority

complex also makes many reticent to criticize a majority

black government and hold them accountable. Many are of

the view that such criticism would reflect badly on black

people. This is a sad reflection on us - it is as if black people

are defined by the incompetent, corrupt and unaccountable

amongst public servants in our society. Why should we be

willing to lower our expectations of public servants because

they are black? Have we bought into the lie that black

people are not capable of higher standards of performance?

To add to the complexity, a superiority complex is still at play

amongst many white people in my society. Many of those

living with this complex believe that their affluence and

higher quality of skills and expertise is proof of their

superiority. The link to the legacy of privilege under

extractive exclusionary economic and political institutions, is

underplayed. The capacity for empathy with those burdened

by structural inequalities resulting from apartheid social

engineering is undermined by this delinking of historic

advantages and current wealth. Many business people boast

that they have never made as much money as they are now

9

in post-apartheid South Africa. One would hope that such a

sentiment would lead to consideration of what more they

could do to reduce the levels of growing inequality in our

society that threaten the sustainability of their prosperity.

The transformation of our society into a more vibrant and fair

one is undermined by the toxic mix of the persistent

inferiority complex amongst a significant majority of black

people and the superiority complex of many white people.

Acknowledging this toxic mix would enable us to tackle it and

unleash our collective creative juices to build a society that

can be more prosperous and fair in a sustainable way.

African nations failure to develop inclusive economic and

political institutions has set off a vicious cycle. We are losing

some of the best brains to nations that are more inclusive. It

is estimated that one in nine Africa born graduates emigrate

to one of the 34 OECD countries. 43% of Zimbabweans, 36%

of DRC and 41% of Mauritian graduates live outside of their

countries of birth. There are more African graduates living in

OECD countries over the last 5 years (450 000), than Chinese

(375 000). These are worrying figures given that there are far

more Chinese who graduate than Africans, worsening the

impact of the loss of African graduates. There is a chicken

and egg situation in Africas development realities. Building

vibrant fairer societies requires human and intellectual

capital, but non-transparent unaccountable governance

10

discourages those most qualified from staying in their

countries to contribute to development.

How can Africa Build more Vibrant and Fair Societies?

Africa has to find a way of building on the enormous human,

natural and mineral resources to become a vibrant fair

continent. It is essential to break free of the vicious cycle of

extractive dominance politics that define in and out groups

ans enter into a virtuous one that leverages the huge human

and intellectual potential to create successful sustainable

development led by transparent accountable governments.

The question is how one develops strategies that counter the

prevailing dominance extractive economic and political

institutional model? What triggers such a process of change

in political culture? Who are the players to make it happen?

The concept of citizenship has yet to take root in post-

colonial Africa. Citizens in most countries are treated as

voting fodder for those in power to retain their positions

regardless of their performance in government. The political

process has turned into transactional relationships between

citizens who are wooed to vote in exchange for some

material good: food parcels, blankets, housing, promises of

jobs and other patronage. These are the hallmarks of

extractive politics. Even the vote is reduced to a tradable

good rather than a tool for citizens to use to hold those in

power accountable by rewarding and punishing governments

11

on the basis of their performance in promoting prosperity for

all.

Citizens as shareholders of their nations have a responsibility

not only to themselves and their interests, but to future

generations who will inherit the institutions they build. It is

this trans-generational responsibility that defines mature

citizenship in inclusive economic and political systems. Just

as shareholders are inducted into their roles as custodians of

the prosperity of the companies they own, so too should

Africa invest more in civic education from the school level all

the way to tertiary education. Most mature democracies

invest in such programs to great effect.

History teaches us that although vicious cycles of extractive

institutions are not easy to break, it can and has been done.

At the heart of such a transformation process is the citizen as

the actor in history. Post-colonial Africa has seen a

marginalization of the best able and talented innovators from

the economic and political institution building process

because they are often seen as a threat to those in power.

The unfortunate though understandable reaction of these

talented Africans has been to quit and seek greener pastures

elsewhere.

The confluence of factors needed for change often presents

itself at unexpected moments, but citizens who desire

12

change must also be willing to take the risk to create the

environment for change. For example, teachers, business

people, faith based leaders and other civic minded people

have many opportunities to raise the bar in their day to day

engagements. Such engagements are particularly important

with young people about what citizens should expect of their

governments and public servants.

Building a higher civic consciousness of alternative

approaches to development and pointing to examples of

nations that succeed versus those that fail is essential. The

Black Consciousness Movement in the 1970s paved the way

for the coalition of students, trade unions, faith based

leaders and civic associations to form the Mass Democratic

Movement in the 1980-90s that ultimately challenged

apartheid and forced a political settlement. At the end of the

day citizens have to be ready to fight for more inclusive

economic and political institutions. Citizens have to fight to

open more doors to technological innovation and greater

prosperity for all. Equality is better for everyone in society.

But equality has to be fought for by all citizens who stand to

benefit.

The unfortunate failure of post-apartheid South Africa to

dismantle extractive economic and political institutions has

resulted in persistent inequality, instability and poverty for

the majority. The settlement compromise of 1994 needed to

have been followed up by deliberate building of inclusive

13

institutions as set out in the Constitution. We also needed to

learn from the German re-unification process and created an

equalization fund (derived from extra tax from those above

an agreed income level over 20 years or so) to build the

education and social infrastructure to ensure that citizens

progressively enjoyed equal access to opportunities and

growing prosperity.

The moment to introduce this equalization fund presented

itself at the height of the euphoria about reconciliation and

living in harmony as a nation united in our diversity, but it

was not harnessed by our political and business leaders. We

missed the boat. But can the post-Marikana blues and the

turmoil of prolonged strike action in the economy be another

opportunity for building coalitions for change towards more

inclusive political-economic institutions?

Africa has a rich heritage. We need to leverage the

philosophical foundation for equality in Ubuntu to develop

institutional cultures driven by the values of inclusivity.

Africa also has poignant examples of nations that succeed

(Botswana) as well as those that fail such as Zimbabwe and

Somalia. Prosperity in Botswana has shown that natural and

mineral resources do not have to be a curse, as is the case in

the DRC or Angola. Botswana under Presidents Seretse

Khama and Quitte Masire ensured that diamonds became a

shared resource that funded infrastructure, education and

innovation investments. Botswana has also progressed to

14

insisting on participating in the higher value chain benefits of

cutting and polishing diamonds on its own soil, creating

greater prosperity.

We need to learn a lot more from one another as African

countries to understand the political-economy of poverty and

prosperity. Prosperity is not a zero sum game the more

people share in it, the more prosperous everyone becomes

as more doors are opened to investment, innovation and

technological advance.

As Africans we need to abandon the idea that the poor will

always be with us. Poverty is expensive for everyone.

Prosperity is possible if we commit to investing in the human

capacity and capability of every citizen to contribute to the

greater good. Women as a neglected majority everywhere in

Africa and the world. But Africa can least afford to ignore the

women who keep families together and produce the food

and other necessities to keep them alive and growing.

Gender equality is the biggest missed opportunity for Africa.

We dare not continue on this pathway if we want to create

vibrant and more equal societies. Harnessing the power of

the feminine will strengthen the masculine is a

complementary way that builds strong families, communities

and societies.

15

How can Africa build more Transparent Accountable

Systems of Governance?

Transparency is the sunshine that disinfects all dark corners

in private and public life. Independent media and access to

information are twin pillars of inclusive economic and

political institutional governance systems. Citizens need

information about the conduct of economic and political

affairs of their nation to be able to participate in the process

of governance and to hold those in power accountable.

Active citizenship is key to transparent accountable

governance. Attaching greater value to the voice of citizens

requires a radical change from the transactional politics of

extractive institutions to the inclusive politics where citizens

are asserting themselves as the owners of the nation state.

The governments in such a setting become the agents of

citizens and are accountable to citizens.

The information technological revolution has made access

and sharing of information much easier and faster. The

North African Spring that challenged the extractive economic

and political systems of Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, was enabled

by information technology. The question remains about why

Sub-Saharan Africa has remained largely untouched by the

North African Spring? Why did young people in SSA not

emulate their North African peers? Could it be that many

16

young people in SSA have either given up on the notion of

change or that they have chosen to bid their time?

The Social Media platforms are abuzz with creative energy.

The question is whether this becomes a creative destructive

force for change or just a pass- time distraction from the

daily grind of marginal existence? To what extent are inter-

generational coalitions being built by leveraging the power of

social media? How much attention do change agents pay to

reaching out to others to mobilize fellow citizens to keep

hope alive?

Transparency promotes accountability. At its very base, the

threat of being named and shamed constrains leaders in both

public and private sectors from acting with impunity. Access

to information about the performance of economic and

political institutions is an essential tool for active citizenship.

It is not surprising that governments in extractive

institutional settings tend to spend a lot of energy in

undermining access to information. Protection of

information is the euphemism often used to block citizens

from gaining access to information sources about matters of

public interest.

The global community is now an open space for all to learn

about what others are doing, and about what works and

what doesnt and why. A focus on promoting access to

17

information, transparency in the conduct of public matters in

both economic and political spheres and use of information

to hold those in power accountable, is the responsibility of all

citizens. Political leaders are increasingly unable to control

access to and use of information to hold them accountable.

There is now a greater opportunity to mobilize across

boundaries to demand change towards greater transparency

and accountability.

Conclusion

There has never been a better moment for change in Africa

than now. We have learnt from our failures to transform

extractive economic and political institutions into more

inclusive ones. We have also learnt about what makes for

success in countries with inclusive economic and political

institutions. As Africans we need to invest a lot more in

building inclusive institutions. A focus on personal extractive

economics and politics has left our continent with gross

inequalities. The politics of poverty and inequality can only

be transformed by a commitment by Africas citizens to take

ownership as custodians of our great continent. It starts with

you and me today.

Dr. Mamphela Ramphele

12/8/2014

You might also like

- State of The Nation Address 2023Document51 pagesState of The Nation Address 2023The New VisionNo ratings yet

- President Museveni's 2023/24 Budget SpeechDocument7 pagesPresident Museveni's 2023/24 Budget SpeechThe New Vision0% (1)

- President Museveni End of Year Message 2023Document11 pagesPresident Museveni End of Year Message 2023The New VisionNo ratings yet

- President Museveni's Heroes Day 2022 SpeechDocument9 pagesPresident Museveni's Heroes Day 2022 SpeechThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- President Museveni's Speech As Uganda Celebrated 60 Years of IndependenceDocument31 pagesPresident Museveni's Speech As Uganda Celebrated 60 Years of IndependenceThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- President Museveni's End of Year AddressDocument34 pagesPresident Museveni's End of Year AddressThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- Executive Order No. 3 of 2023Document18 pagesExecutive Order No. 3 of 2023The New VisionNo ratings yet

- 58TH Independence Anniversary Speech by President Yoweri MuseveniDocument13 pages58TH Independence Anniversary Speech by President Yoweri MuseveniGCICNo ratings yet

- List of Successful Candidates General Duties & DriversDocument25 pagesList of Successful Candidates General Duties & DriversThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- Ruling Aine Godfrey Kaguta Sodo V NRM & AnotherDocument23 pagesRuling Aine Godfrey Kaguta Sodo V NRM & AnotherThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- President Museveni's Speech On World Teachers Day 2020Document12 pagesPresident Museveni's Speech On World Teachers Day 2020The New VisionNo ratings yet

- Final Admission List of Students To Government Health Training CollegesDocument298 pagesFinal Admission List of Students To Government Health Training CollegesThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- State of The Nation Address 2022Document32 pagesState of The Nation Address 2022The New VisionNo ratings yet

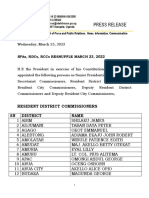

- SPAs, RDCS, RCCs ReshuffledDocument12 pagesSPAs, RDCS, RCCs ReshuffledThe New Vision100% (3)

- President Yoweri Museveni's Speech at TICADDocument10 pagesPresident Yoweri Museveni's Speech at TICADThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- Presidential Address On The National LockDownDocument22 pagesPresidential Address On The National LockDownMujuni Raymond Carlton QataharNo ratings yet

- Cabinet 2019/20Document13 pagesCabinet 2019/20The New Vision80% (5)

- Dorothy Kisaka Inauguration SpeechDocument9 pagesDorothy Kisaka Inauguration SpeechThe New Vision100% (1)

- 2018 State of The Nation Address UgandaDocument30 pages2018 State of The Nation Address UgandaThe Independent MagazineNo ratings yet

- First Lady's Address On The Reopening of SchoolsDocument9 pagesFirst Lady's Address On The Reopening of SchoolsThe New Vision100% (1)

- New CabinetDocument15 pagesNew CabinetThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- Private Admission List 2017/18Document1,052 pagesPrivate Admission List 2017/18The New Vision95% (19)

- Press Release 230216Document6 pagesPress Release 230216The New VisionNo ratings yet

- State of The Nation Address 2017Document26 pagesState of The Nation Address 2017The New Vision67% (3)

- President Museveni Statement at The Somalia Conference London 2017Document9 pagesPresident Museveni Statement at The Somalia Conference London 2017The Independent Magazine50% (2)

- Press Release 230216Document6 pagesPress Release 230216The New VisionNo ratings yet

- New RDCs & Deputy RDCsDocument16 pagesNew RDCs & Deputy RDCsThe New Vision100% (2)

- Government Response To HRW Report On KaseseDocument5 pagesGovernment Response To HRW Report On KaseseThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- Luwum Public HolidayDocument1 pageLuwum Public HolidayThe New VisionNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- People of The Philippines,: DecisionDocument12 pagesPeople of The Philippines,: DecisionGlendie LadagNo ratings yet

- Anaya Cruz Rec ReconsideracDocument6 pagesAnaya Cruz Rec ReconsideracElkins Guivar OrtizNo ratings yet

- People V SabioDocument1 pagePeople V SabioPNP MayoyaoNo ratings yet

- Expungement Va LawDocument2 pagesExpungement Va LawJS100% (1)

- Fisheries Jurisdiction CaseDocument2 pagesFisheries Jurisdiction CaseJohnKyleMendozaNo ratings yet

- McGarry v. Bucket Innovations - ComplaintDocument23 pagesMcGarry v. Bucket Innovations - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Systems Factors Corporation and Modesto Dean V NLRCDocument2 pagesSystems Factors Corporation and Modesto Dean V NLRCJessie Albert CatapangNo ratings yet

- Intro PPT 2 - CHAPTER 2 - CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMDocument19 pagesIntro PPT 2 - CHAPTER 2 - CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMKenneth PuguonNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- 3 Things To Know About SNAPDocument4 pages3 Things To Know About SNAPHamilton Place StrategiesNo ratings yet

- EAPP Position Paper 1Document3 pagesEAPP Position Paper 1Ruby Rosios60% (5)

- The Importance of Governance and Development and Its Interrelationship (Written Report)Document6 pagesThe Importance of Governance and Development and Its Interrelationship (Written Report)Ghudz Ernest Tambis100% (3)

- Midterm Transcript 15-16Document76 pagesMidterm Transcript 15-16MikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Labor Relations Case Digests 1Document7 pagesLabor Relations Case Digests 1Macy TangNo ratings yet

- Midlands State University Faculty of Arts Department of Development StudiesDocument10 pagesMidlands State University Faculty of Arts Department of Development StudiesShax BwoyNo ratings yet

- Centra MTRDocument15 pagesCentra MTRfleckaleckaNo ratings yet

- All Kinds of Diplomatic NoteDocument90 pagesAll Kinds of Diplomatic NoteMarius C. Mitrea60% (5)

- Manuel vs. PeopleDocument2 pagesManuel vs. PeopleAtty Ed Gibson BelarminoNo ratings yet

- Benefits & PrivilegesDocument40 pagesBenefits & Privilegesnavdeepsingh.india884988% (25)

- A Brief Overview of The Supreme CourtDocument2 pagesA Brief Overview of The Supreme CourtJerik SolasNo ratings yet

- How To Recruit A SpyDocument1 pageHow To Recruit A SpygjemsonNo ratings yet

- Globe Mackay Cable and Radio Corporation vs. NLRCDocument3 pagesGlobe Mackay Cable and Radio Corporation vs. NLRCRhev Xandra Acuña100% (4)

- Napoleon BonaparteDocument11 pagesNapoleon BonaparteChido MorganNo ratings yet

- Confidentiality, RraDocument9 pagesConfidentiality, RraQuisha Kay100% (1)

- Anushka Admit Card FirDocument1 pageAnushka Admit Card FirRahul KumarNo ratings yet

- Sources of Law PDFDocument35 pagesSources of Law PDFsanshlesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Calvary Skate Park WaiverDocument2 pagesCalvary Skate Park WaiverCarissa NicholsNo ratings yet

- Digest JijDocument9 pagesDigest JijjannagotgoodNo ratings yet

- Case Digest JursdictionDocument29 pagesCase Digest JursdictionPhrexilyn PajarilloNo ratings yet

- Moppets Worker ApplicationDocument3 pagesMoppets Worker Applicationapi-89463374No ratings yet