Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SPLC Letter of Concern, August 14, 2014

Uploaded by

aamcwhorterOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SPLC Letter of Concern, August 14, 2014

Uploaded by

aamcwhorterCopyright:

Available Formats

rX/

PLC

STUDENT PRESS LAW CENTER

August 14, 2014

Dr. Karen Baldwin, Vice President for University Advancement

The University of Alabama

284 Rose Administration Building

Box 870122

Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0122

VIA FACSIMILE

Dear Vice President Baldwin,

The Student Press Law Center provides legal research and advocacy in support of

those working in student media nationally. We were concerned to read media accounts

describing restrictions placed on news coverage of sorority rush events at the University

of Alabama, following last years publication of the Pulitzer-nominated investigative

report by journalists at The Crimson White about the role of race in the selection

process.

We have reviewed the memorandum (Guidelines for Media covering Sorority

Recruitment, henceforth simply referred to as Media Guidelines) disseminated by the

Office of University Relations. While it is perfectly legitimate for the University to

remind journalists not to engage in illegal trespassing (i.e., encroaching on front

yards) and to regulate parking and traffic, that is where the Universitys lawful

authority ends.

We are particularly concerned about the directives in the Media Guidelines

purporting to prohibit consensual communications between members of the media and

individual students who may wish to speak with them:

No representative from UA Greek Affairs, the Panhellenic

Executive Council or any sororities will be available for interviews

during Sorority Recruitment Week (emphasis added)

All questions should be directed to University Relations.

No representative from UA Greek Affairs, the Panhellenic

Executive Council or any sororities will be available for interviews on

Bid Day (emphasis added).

To the extent that the University is purporting to use its regulatory authority to restrict

consensual communications between students and the news media about matters of

public concern, such a gag order contravenes basic First Amendment principles.

1101 Wilson BIvd, Suite 1100 Arlington, VA 222092211 B 703807l904 B spIc@splcorg www,splcorg

Government restrictions on contacts with the news media regularly are struck

down in the courts as overly broad and unjustified by any compelling government

priority. See, e.g., Harman v. City ofNew York, 140 F.3d 111 (2d Cir. 1998)

(requirement that employees obtain pre-approval by Media Relations Office of city

social service agency before making contacts with media was unconstitutionally

overbroad); Spain v. City ofMansfield, 915 F. Supp. 919 (N.D. Ohio 1996) (fire

department rules requiring approval before assistant fire chiefs were permitted to speak

out on fire department matters were facially unconstitutional); Wolf V. City of

Aberdeen, 758 F. Supp. 551 (D.S.D. 1991) (municipal ordinance prohibiting city

employees from commenting on internal business decisions or department rules and

regulations without prior approval was unconstitutionally overbroad). See also Intl

Assn ofFirefighters Local 3233 v. Frenchtown Charter Twp., 246 F. Supp.2d

734,

738

(E.D. Mich. 2003) (ordinance designating fire chief as sole spokesman to media was

facially unconstitutional); Wagner u. City ofHolyoke, 100 F.Supp.2d 78 (D. Mass.

2000) (rule barring release of information to the media by all but chief of police or his

designee was unconstitutionally overbroad); Salerno v. ORourke,

555

F. Supp. 750

(D.N.J. 1983) (proscription against jail employee giving information to newspaper

representatives or any other person without the consent of the sheriff is so

overinclusive facially as to be unconstitutional).

While there is ample legal authority that institutions may not enforce blanket gag

orders on their employees, there frankly is scarce legal authority addressing a colleges

ability to gag its students, because to our knowledge no college has been audacious

enough to try. Nevertheless, an institutions control over its employees speech is greater

than its control over student speech, since employee speech is at times regarded as

government speech, see Garcetti v. Ceballos,

547

U.S. 410 (2006), while student

speech is not. Consequently, a policy that would be unlawful when applied to employees

is patently unlawful if applied to students. See generally Tinker v. Des Moines Indep.

Cmty. Sch. Dist.,

393

U.S. 503 (1969) (public school may not restrict or penalize

students in-school speech unless the regulation is necessary to avoid material and

substantial interference with schoolwork or discipline).

We are concerned, as well, about purported restrictions on howjournalists may

approach sources to request interviews. Unless there is a blanket policy that no visitor

may knock on the door of a Greek house, it violates the First Amendment for a

government agency to selectively exclude only journalists. See generally Fell v.

Procunier, 417 U.S. 817 (1974) (holding that, while the First Amendment does not

guarantee the news media preferential access to interview opportunities, the medias

right of access is equivalent to that of the general public). If a member of the public

inquiring about membership or conducting a political survey is permitted to knock on

the door and ask to speak with someone inside, members of the news media may not be

singled out for differentially disfavored access. Of course, members of sororities are

under no obligation to grant interviews and it may be their preference to refuse, but the

decision belongs to them and not to University authorities.

Legal considerations aside, obstructing access to sorority rush events is a

profoundly misguided public-relations strategy that is guaranteed to backfire. If there

was ever a time for greater transparency in the selection process, it is after the integrity

of the process has been discredited. The public has an interest in knowing whether

am-thing has been learned from the events of last year. Canned quotes from a

spokesperson who is not in the room where decisions are made will do nothing to

reassure the public. To the contrary, the Universitys handling of media inquiries smacks

of an intent to conceal and obfuscate.

It cannot go unremarked that the disclosures published in last years Crimson

White article, The Final Barrier, came about because members of Greek organizations

broke ranks and did consent to speak with the news media about the outrages they

witnessed, at times against the wishes of those supervising their organizations. If an

individual sorority wishes to enforce a no-interviews rule with consequences to be

imposed within the sorority, that is a private matter and the misjudgment will be their

private concern. But a government agency cannot, and should not, serve as the enforcer

of a policy calculated to make sure that whistleblowers cannot come forward with

exactly the sort of information on which The Crimson Whites groundbreaking reporting

was based.

It is incumbent on the University to immediately and unequivocally clarify (i)

that students are free to speak with journalists without fear of reprisal from the

institution, and (2) that journalists (in particular student journalists, who are paying

customers entitled to be on your campus) are equally free to contact students to

determine their interest in speaking. We ask that you make a public declaration to dispel

the impression left by the Media Guidelines that the University believes it can enforce a

gag order on its own students.

Respectfully

Frank D. LoMonte, Esq.

Executive Director

Student Press Law Center

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Draft PDFDocument166 pagesDraft PDFashwaq000111No ratings yet

- E-Versuri Ro - Rihana - UmbrelaDocument2 pagesE-Versuri Ro - Rihana - Umbrelaanon-821253100% (1)

- ADC of PIC MicrocontrollerDocument4 pagesADC of PIC Microcontrollerkillbill100% (2)

- C4 Vectors - Vector Lines PDFDocument33 pagesC4 Vectors - Vector Lines PDFMohsin NaveedNo ratings yet

- Mozal Finance EXCEL Group 15dec2013Document15 pagesMozal Finance EXCEL Group 15dec2013Abhijit TailangNo ratings yet

- Google Tools: Reggie Luther Tracsoft, Inc. 706-568-4133Document23 pagesGoogle Tools: Reggie Luther Tracsoft, Inc. 706-568-4133nbaghrechaNo ratings yet

- 2-1. Drifting & Tunneling Drilling Tools PDFDocument9 pages2-1. Drifting & Tunneling Drilling Tools PDFSubhash KediaNo ratings yet

- Lab Report SBK Sem 3 (Priscilla Tuyang)Document6 pagesLab Report SBK Sem 3 (Priscilla Tuyang)Priscilla Tuyang100% (1)

- TraceDocument5 pagesTraceNorma TellezNo ratings yet

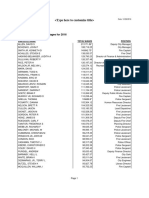

- 2016 W-2 Gross Wages CityDocument16 pages2016 W-2 Gross Wages CityportsmouthheraldNo ratings yet

- EKRP311 Vc-Jun2022Document3 pagesEKRP311 Vc-Jun2022dfmosesi78No ratings yet

- Grid Pattern PortraitDocument8 pagesGrid Pattern PortraitEmma FravigarNo ratings yet

- Binge Eating Disorder ANNADocument12 pagesBinge Eating Disorder ANNAloloasbNo ratings yet

- Binary OptionsDocument24 pagesBinary Optionssamsa7No ratings yet

- Ring and Johnson CounterDocument5 pagesRing and Johnson CounterkrsekarNo ratings yet

- Aliping PDFDocument54 pagesAliping PDFDirect LukeNo ratings yet

- MEd TG G07 EN 04-Oct Digital PDFDocument94 pagesMEd TG G07 EN 04-Oct Digital PDFMadhan GanesanNo ratings yet

- Open Source NetworkingDocument226 pagesOpen Source NetworkingyemenlinuxNo ratings yet

- Solubility Product ConstantsDocument6 pagesSolubility Product ConstantsBilal AhmedNo ratings yet

- NIQS BESMM 4 BillDocument85 pagesNIQS BESMM 4 BillAliNo ratings yet

- Organization Culture Impacts On Employee Motivation: A Case Study On An Apparel Company in Sri LankaDocument4 pagesOrganization Culture Impacts On Employee Motivation: A Case Study On An Apparel Company in Sri LankaSupreet PurohitNo ratings yet

- Kosher Leche Descremada Dairy America Usa Planta TiptonDocument2 pagesKosher Leche Descremada Dairy America Usa Planta Tiptontania SaezNo ratings yet

- 1 Bacterial DeseaseDocument108 pages1 Bacterial DeseasechachaNo ratings yet

- (Campus of Open Learning) University of Delhi Delhi-110007Document1 page(Campus of Open Learning) University of Delhi Delhi-110007Sahil Singh RanaNo ratings yet

- Haier in India Building Presence in A Mass Market Beyond ChinaDocument14 pagesHaier in India Building Presence in A Mass Market Beyond ChinaGaurav Sharma100% (1)

- Poetry UnitDocument212 pagesPoetry Unittrovatore48100% (2)

- Notes On Antibodies PropertiesDocument3 pagesNotes On Antibodies PropertiesBidur Acharya100% (1)

- Brigade Product Catalogue Edition 20 EnglishDocument88 pagesBrigade Product Catalogue Edition 20 EnglishPelotudoPeloteroNo ratings yet

- Ecs h61h2-m12 Motherboard ManualDocument70 pagesEcs h61h2-m12 Motherboard ManualsarokihNo ratings yet

- 1Document3 pages1Stook01701No ratings yet