Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ampatuan V de Lima

Uploaded by

Errica Marie De GuzmanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ampatuan V de Lima

Uploaded by

Errica Marie De GuzmanCopyright:

Available Formats

REMEDIAL LAW REVIEW Criminal Procedure

Atty Brondial

Lecture 8 Case Digests

1

Ampatuan v Sec. Leila de Lima (2013)

Bersamin, J.

DOCTRINE

In matters involving the exercise of judgment and discretion, mandamus cannot be used to

direct the manner or the particular way the judgment and discretion are to be exercised.

Consequently, the Secretary of Justice may be compelled by writ of mandamus to act on a

letter-request or a motion to include a person in the information, but may not be

compelled by writ of mandamus to act in a certain way, i.e., to grant or deny such letter-

request or motion.

FACTS

The panel of prosecutors charged 196 individuals with multiple murder in relation to the

Maguindanao Massacre. The resolution of the panel partly relied on the twin affidavits of

Kenny Dalandag.

Dalandag was admitted into the Witness protection program of DOJ. He was listed as one

of the prosecution witnesses.

Petitioner, through counsel, wrote to respondent Secretary de Lima to request the

inclusion of Dalandag in the informations for musrder considering that Dalandag had

already confessed his participation in the massacre. Secretary de Lima, in her letter,

denied petitioners request.

Petitioner filed before RTC of Manila a petition for mandamus seeking to

compel respondents to charge Dalandag as another accused in the various

murder cases undergoing trial.

ISSUE

Whether respondents may be compelled by writ of mandamus to charge Dalandag as an

accused for multiple murder in relation to the Maguindanao massacre despite his

admission to the Witness Protection Program of the DOJ.

HELD:

No, respondent Secretary of Justice may be compelled to act on the

letter-request of petitioner, but may not be compelled to act in a

certain way, i.e., to grant or deny such letter-request. Considering

that respondent Secretary of Justice already denied the letter-

request, mandamus was no longer available as petitioner's recourse.

Consistent with the principle of separation of powers enshrined in the Constitution, the

Court deems it a sound judicial policy not to interfere in the conduct of preliminary

investigations, and to allow the Executive Department, through the Department of Justice,

exclusively to determine what constitutes sufficient evidence to establish probable cause

for the prosecution of supposed offenders. By way of exception, however, judicial review

may be allowed where it is clearly established that the public prosecutor committed grave

abuse of discretion, that is, when he has exercised his discretion "in an arbitrary,

capricious, whimsical or despotic manner by reason of passion or personal hostility, patent

and gross enough as to amount to an evasion of a positive duty or virtual refusal to

perform a duty enjoined by law."

The records herein are bereft of any showing that the Panel of Prosecutors committed

grave abuse of discretion in identifying the 196 individuals to be indicted for the

Maguindanao massacre.

The two modes by which a participant in the commission of a crime may

become a state witness are, namely:

(a) by discharge from the criminal case pursuant to Section 17 of Rule 119 of the

Rules of Court; and

(b) by the approval of his application for admission into the Witness Protection

Program of the DOJ in accordance with Republic Act No. 6981 (The Witness

Protection, Security and Benefit Act).

These modes are intended to encourage a person who has witnessed a crime or

who has knowledge of its commission to come forward and testify in court or

quasi-judicial body, or before an investigating authority, by protecting him from

reprisals, and shielding him from economic dislocation.

Under Section 17, Rule 119 of the Rules of Court, the discharge by the trial court of

one or more of several accused with their consent so that they can be witnesses for the

State is made upon motion by the Prosecution before resting its case.

The trial court shall require the Prosecution to present evidence and the sworn

statements of the proposed witnesses at a hearing in support of the discharge.

The trial court must ascertain if the following conditions fixed by Section 17 of

Rule 119 are complied with, namely:

(a) there is absolute necessity for the testimony of the accused whose discharge

is requested;

(b) there is no other direct evidence available for the proper prosecution of the

offense committed, except the testimony of said accused;

(c) the testimony of said accused can be substantially corroborated in its

material points;

(d) said accused does not appear to be most guilty; and

(e) said accused has not at any time been convicted of any offense involving

moral turpitude.

On the other hand, Section 10 of Republic Act No. 6981 provides:

REMEDIAL LAW REVIEW Criminal Procedure

Atty Brondial

Lecture 8 Case Digests

2

Section 10. State Witness. Any person who has participated in the commission

of a crime and desires to be a witness for the State, can apply and, if qualified as

determined in this Act and by the Department, shall be admitted into the

Program whenever the following circumstances are present:

a. the offense in which his testimony will be used is a grave felony as defined

under the Revised Penal Code or its equivalent under special laws;

b. there is absolute necessity for his testimony;

c. there is no other direct evidence available for the proper prosecution of the

offense committed;

d. his testimony can be substantially corroborated on its material points;

e. he does not appear to be most guilty; and

f. he has not at any time been convicted of any crime involving moral turpitude.

An accused discharged from an information or criminal complaint by the court in

order that he may be a State Witness pursuant to Section 9 and 10 of Rule 119 of

the Revised Rules of Court may upon his petition be admitted to the Program if

he complies with the other requirements of this Act. Nothing in this Act shall

prevent the discharge of an accused, so that he can be used as a State

Witness under Rule 119 of the Revised Rules of Court.

Save for the circumstance covered by paragraph (a) of Section 10, supra, the

requisites under both rules are essentially the same. Also worth noting is that an

accused discharged from an information by the trial court pursuant to Section 17 of Rule

119 may also be admitted to the Witness Protection Program of the DOJ provided he

complies with the requirements of Republic Act No. 6981.

A participant in the commission of the crime, to be discharged to become a

state witness pursuant to Rule 119, must be one charged as an accused in the

criminal case. The discharge operates as an acquittal of the discharged accused and

shall be a bar to his future prosecution for the same offense, unless he fails or refuses to

testify against his co-accused in accordance with his sworn statement constituting the

basis for his discharge.

The discharge is expressly left to the sound discretion of the trial

court, which has the exclusive responsibility to see to it that the conditions

prescribed by the rules for that purpose exist.

While it is true that, as a general rule, the discharge or exclusion of a co-accused

from the information in order that he may be utilized as a Prosecution witness

rests upon the sound discretion of the trial court,

such discretion is not absolute

and may not be exercised arbitrarily, but with due regard to the proper

administration of justice. Anent the requisite that there must be an absolute

necessity for the testimony of the accused whose discharge is sought, the trial

court has to rely on the suggestions of and the information provided by the public

prosecutor.

The reason is obvious the public prosecutor should know better than the trial

court, and the Defense for that matter, which of the several accused would best

qualify to be discharged in order to become a state witness.

The public prosecutor is also supposed to know the evidence in his possession

and whomever he needs to establish his case, as well as the availability or non-

availability of other direct or corroborative evidence, which of the accused is the

most guilty one, and the like.

On the other hand, there is no requirement under Republic Act No. 6981 for

the Prosecution to first charge a person in court as one of the accused in

order for him to qualify for admission into the Witness Protection Program.

The admission as a state witness under Republic Act No. 6981 also operates as an

acquittal, and said witness cannot subsequently be included in the criminal

information except when he fails or refuses to testify. The immunity for the state

witness is granted by the DOJ, not by the trial court. Should such witness be

meanwhile charged in court as an accused, the public prosecutor, upon

presentation to him of the certification of admission into the Witness Protection

Program, shall petition the trial court for the discharge of the witness. The Court

shall then order the discharge and exclusion of said accused from the

information.

The admission of Dalandag into the Witness Protection Program of the

Government as a state witness since August 13, 2010 was warranted by the

absolute necessity of his testimony to the successful prosecution of the

criminal charges. Apparently, all the conditions prescribed by Republic Act

No. 6981 were met in his case. That he admitted his participation in the commission

of the Maguindanao massacre was no hindrance to his admission into the Witness

Protection Program as a state witness, for all that was necessary was for him to appear not

the most guilty. Accordingly, he could not anymore be charged for his participation in the

Maguindanao massacre, as to which his admission operated as an acquittal, unless he later

on refuses or fails to testify in accordance with the sworn statement that became the basis

for his discharge against those now charged for the crimes.

You might also like

- Datu Ampatuan Vs Sec. Leila de LimaDocument2 pagesDatu Ampatuan Vs Sec. Leila de LimaMaria Angela SangreNo ratings yet

- Ampatuan, Jr. vs. de LimaDocument12 pagesAmpatuan, Jr. vs. de LimaJohzzyluck R. MaghuyopNo ratings yet

- Ampatuan vs. de LimaDocument6 pagesAmpatuan vs. de LimaRocky MagcamitNo ratings yet

- Ampatuan v. de LimaDocument1 pageAmpatuan v. de LimaRegina CoeliNo ratings yet

- State WitnessDocument7 pagesState WitnessjeffdelacruzNo ratings yet

- Sec. 17, Rule 119 Hubert Webb v. Judge de LeonDocument3 pagesSec. 17, Rule 119 Hubert Webb v. Judge de LeonGLORILYN MONTEJONo ratings yet

- Ampatuan v. de LimaDocument21 pagesAmpatuan v. de LimaJD greyNo ratings yet

- Yu VS RTC JudgeDocument5 pagesYu VS RTC JudgeD Del SalNo ratings yet

- Webb V de Leon 247 Scra 652Document3 pagesWebb V de Leon 247 Scra 652Jenine QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- 106 VILLAVICENCIO Ampatuan Jr. v. de LimaDocument2 pages106 VILLAVICENCIO Ampatuan Jr. v. de LimaSalve VillavicencioNo ratings yet

- Webb Vs de Leon (1995) - Summary PDFDocument4 pagesWebb Vs de Leon (1995) - Summary PDFJNo ratings yet

- Bathan NotesDocument10 pagesBathan NotesJpee HernandezNo ratings yet

- No95 VE Gana1Document11 pagesNo95 VE Gana1Kristina Carmela SoNo ratings yet

- Patula v. PeopleDocument25 pagesPatula v. PeopleNinaNo ratings yet

- Lavides vs. CA Facts:: After His Arraignment"Document6 pagesLavides vs. CA Facts:: After His Arraignment"Caroline A. LegaspinoNo ratings yet

- Building A Criminal CaseDocument11 pagesBuilding A Criminal CaseAnonymous GMUQYq8No ratings yet

- de Jesus - 2B - CRIMPRO RULE 119 CASE NOTESDocument37 pagesde Jesus - 2B - CRIMPRO RULE 119 CASE NOTESAbigael SeverinoNo ratings yet

- D Cases For ReportDocument6 pagesD Cases For ReportCharmagneNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Notes Rule 110Document5 pagesCriminal Procedure Notes Rule 110shienna baccayNo ratings yet

- Appellee Vs Vs Appellants: Second DivisionDocument13 pagesAppellee Vs Vs Appellants: Second DivisionJanine FabeNo ratings yet

- CLAW 6 Notes 2Document8 pagesCLAW 6 Notes 2Jenray DacerNo ratings yet

- Ampatuan vs. de LimaDocument18 pagesAmpatuan vs. de LimaisaaabelrfNo ratings yet

- Patula vs. PeopleDocument38 pagesPatula vs. PeopleChristine Gel MadrilejoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure JurisprudenceDocument11 pagesCriminal Procedure JurisprudenceAmariah Queen Aleszia RoldanNo ratings yet

- Evangelista Vs People: JurisdictionDocument10 pagesEvangelista Vs People: JurisdictionKit CruzNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Jose C Claro Florendo C MedinaDocument27 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Jose C Claro Florendo C MedinaKimberly GangoNo ratings yet

- People vs. PagalDocument5 pagesPeople vs. PagalJaysonNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Jose C Claro Florendo C MedinaDocument27 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Jose C Claro Florendo C MedinaIan TaduranNo ratings yet

- Salazar v. PeopleDocument11 pagesSalazar v. PeopleBea HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Complainant Vs Vs Respondents Diosdado C. Sebrio, Jr. Amancio C. Balicud Napoleon Uy Galit and Associates Law OfficesDocument19 pagesComplainant Vs Vs Respondents Diosdado C. Sebrio, Jr. Amancio C. Balicud Napoleon Uy Galit and Associates Law OfficesRon Russell Solivio MagbalonNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure 1900Document19 pagesCriminal Procedure 1900yanNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Yy Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Public Attorney's OfficeDocument14 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Yy Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Public Attorney's OfficePaul Joshua Torda SubaNo ratings yet

- E.G. Under Sec. 8, R.A. 1379, The Law Providing For The Forfeiture of UnlawfullyDocument4 pagesE.G. Under Sec. 8, R.A. 1379, The Law Providing For The Forfeiture of UnlawfullyFlores JoevinNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction DefinitionDocument6 pagesJurisdiction DefinitionJean Monique Oabel-TolentinoNo ratings yet

- 118222-2000-People v. Nadera Jr. y SadsadDocument14 pages118222-2000-People v. Nadera Jr. y SadsadAlyanna CabralNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Final Exam ReviewerDocument8 pagesCriminal Procedure Final Exam Reviewershaneivyg50% (2)

- Rule 119Document58 pagesRule 119Vianne Marie GarciaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Review For BarDocument58 pagesCriminal Procedure Review For BarZaldy Lopez Obel IINo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law 2 - Case DigestsDocument12 pagesConstitutional Law 2 - Case DigestsMArieMigallenNo ratings yet

- People v. CamatDocument12 pagesPeople v. CamatjenzmiNo ratings yet

- Harry Go Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesHarry Go Vs PeopleGabbie LeanoNo ratings yet

- 001 DIGESTS 1 CrimDocument7 pages001 DIGESTS 1 CrimJeromeo Hallazgo de LeonNo ratings yet

- Galvante Vs Casimiro 2008Document16 pagesGalvante Vs Casimiro 2008Joyce WyneNo ratings yet

- 11 Ladiana - v. - PeopleDocument17 pages11 Ladiana - v. - PeopleAlyssa Fatima Guinto SaliNo ratings yet

- 1900 Code of Criminal Procedure of The PhilippinesDocument18 pages1900 Code of Criminal Procedure of The PhilippinesNigel Lorenzo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Floresta v. Ubiada 429 SCRA 270Document16 pagesFloresta v. Ubiada 429 SCRA 270FD BalitaNo ratings yet

- Crmpro Midterms Exam Mod 11Document20 pagesCrmpro Midterms Exam Mod 11Abigael SeverinoNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Respondent Jose A. Almo Angel R. Purisima III The Solicitor GeneralDocument19 pagesPetitioner Respondent Jose A. Almo Angel R. Purisima III The Solicitor GeneralDarla EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Crim Pro Doctrines Remedial Law - CompressDocument98 pagesCrim Pro Doctrines Remedial Law - Compressgutierrez.grace1234No ratings yet

- 2 Pecho - v. - Sandiganbayan20181107-5466-1ef1ro5Document18 pages2 Pecho - v. - Sandiganbayan20181107-5466-1ef1ro5John Paul SuaberonNo ratings yet

- People v. DeriloDocument24 pagesPeople v. DeriloAAMCNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure - Criminology Board Exam ReviewerDocument18 pagesCriminal Procedure - Criminology Board Exam ReviewerJi YongNo ratings yet

- Case Doctrines From Pre-Trial Onwards (CrimPro)Document10 pagesCase Doctrines From Pre-Trial Onwards (CrimPro)Princess Aileen EsplanaNo ratings yet

- Canceran Vs PeopleDocument2 pagesCanceran Vs PeopleRazel May RamonNo ratings yet

- Yap Vs CaDocument4 pagesYap Vs CaM A J esty FalconNo ratings yet

- Motion To Quash SampleDocument7 pagesMotion To Quash SamplePaolo Lim100% (1)

- PANAL CASE Omnibus Motion DraftDocument7 pagesPANAL CASE Omnibus Motion DraftPang RagnaNo ratings yet

- Harry Go Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesHarry Go Vs Peoplecarinokatrina0% (1)

- CasesDocument51 pagesCaseskimuchosNo ratings yet

- American Convention on Human Rights (Pact of San José)From EverandAmerican Convention on Human Rights (Pact of San José)No ratings yet

- Lease, Partnership and AgencyDocument45 pagesLease, Partnership and AgencyErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- CIV2 Contracts (7 February 2015)Document6 pagesCIV2 Contracts (7 February 2015)Errica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Iii. Kinds of Obligations: A. According To Demandability (1179-1192)Document16 pagesIii. Kinds of Obligations: A. According To Demandability (1179-1192)Errica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 2013 People V OdtuhanDocument3 pages2013 People V OdtuhanErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Civ2 Atp (7 March 2015)Document17 pagesCiv2 Atp (7 March 2015)Errica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- CIV2 ATP (7 March 2015)Document17 pagesCIV2 ATP (7 March 2015)Errica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Crim ReportDocument5 pagesCrim ReportErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- CIV 1 FINAL DigestsDocument78 pagesCIV 1 FINAL DigestsErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- CIVREV Digest CompilationDocument272 pagesCIVREV Digest CompilationErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Retail TradeDocument23 pagesRetail TradeErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- IPDocument11 pagesIPErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Gonzaga V CADocument2 pagesGonzaga V CAErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- CIV 1 FINAL DigestsDocument78 pagesCIV 1 FINAL DigestsErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- United States V de Los ReyesDocument2 pagesUnited States V de Los ReyesErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Land Bank of The Philippines V de LeonDocument2 pagesLand Bank of The Philippines V de LeonErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Criminal LawDocument10 pagesCriminal LawErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Constitution LectureDocument6 pagesConstitution LectureErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Rivelisa V First Sta ClaraDocument2 pagesRivelisa V First Sta ClaraErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- PSBA V CA (1992) : FactsDocument1 pagePSBA V CA (1992) : FactsErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- CIV 1 FINAL DigestsDocument78 pagesCIV 1 FINAL DigestsErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- RCBC V CADocument2 pagesRCBC V CAErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Philamcare Health Systems, Inc. V. Ca, Trinos (2002) : Action On The Contract. in This Case, No Rescission Was MadeDocument2 pagesPhilamcare Health Systems, Inc. V. Ca, Trinos (2002) : Action On The Contract. in This Case, No Rescission Was MadeErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Lacson V Executive SecretaryDocument3 pagesLacson V Executive SecretaryErrica Marie De Guzman100% (1)

- Osmena V SSSDocument2 pagesOsmena V SSSErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Manila Bankers Life Insurance Corporation V Eddy NG Kok WeiDocument2 pagesManila Bankers Life Insurance Corporation V Eddy NG Kok WeiErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Balus V BalusDocument1 pageBalus V BalusErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Benguet Exploration V CADocument3 pagesBenguet Exploration V CAErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Asean Pacific Planners V City of UrdanetaDocument2 pagesAsean Pacific Planners V City of UrdanetaErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Asean Pacific Planners V City of UrdanetaDocument2 pagesAsean Pacific Planners V City of UrdanetaErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Philamcare Health Systems, Inc. V. Ca, Trinos (2002) : Action On The Contract. in This Case, No Rescission Was MadeDocument2 pagesPhilamcare Health Systems, Inc. V. Ca, Trinos (2002) : Action On The Contract. in This Case, No Rescission Was MadeErrica Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Gonzales vs. Rufino HechanovaDocument3 pagesGonzales vs. Rufino Hechanovamarc abellaNo ratings yet

- 2019 Escolin Evid Cases Ver. 9Document39 pages2019 Escolin Evid Cases Ver. 9Ellis Lagasca100% (1)

- Mason Vs CADocument2 pagesMason Vs CAana ortiz100% (1)

- ATF Firearms Industry Operations Manual 2017 REVDocument155 pagesATF Firearms Industry Operations Manual 2017 REVAmmoLand Shooting Sports News100% (5)

- David v. Hall, 318 F.3d 343, 1st Cir. (2003)Document7 pagesDavid v. Hall, 318 F.3d 343, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

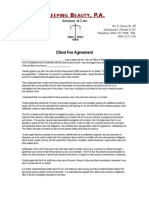

- Client Fee Agreement 20Document2 pagesClient Fee Agreement 20api-326532936No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 218040Document19 pagesG.R. No. 218040Anonymous KgPX1oCfrNo ratings yet

- People vs. Ben RubioDocument2 pagesPeople vs. Ben Rubioclaudenson18No ratings yet

- Revised Penal Code Book 1Document102 pagesRevised Penal Code Book 1miks1981100% (1)

- Gerald Barbaris v. Edsel Taylor, 4th Cir. (2013)Document3 pagesGerald Barbaris v. Edsel Taylor, 4th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 31 Alliance-of-Quezon-City-Homeowners-Association-Inc-vs-the-Quezon-City-Government-DigestDocument2 pages31 Alliance-of-Quezon-City-Homeowners-Association-Inc-vs-the-Quezon-City-Government-Digesthigoremso giensdksNo ratings yet

- Lambert V Heirs of CastillonDocument2 pagesLambert V Heirs of Castillonsamdelacruz1030No ratings yet

- San Andreas State Bar License TermsDocument2 pagesSan Andreas State Bar License TermsShahidullah TareqNo ratings yet

- Sample PleadingDocument4 pagesSample PleadingZyki Zamora LacdaoNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument42 pagesIntroductionShariq AzmiNo ratings yet

- Law 126: Evidence Ma'am Victoria Avena: Drilon1Document65 pagesLaw 126: Evidence Ma'am Victoria Avena: Drilon1cmv mendoza100% (1)

- MOU Between MPD and OCME - Toxicology ReportDocument3 pagesMOU Between MPD and OCME - Toxicology ReportThe Washington PostNo ratings yet

- Doctrines Criminal LawDocument3 pagesDoctrines Criminal LawSam FajardoNo ratings yet

- Have They Delivered? Northern Times (2/2)Document1 pageHave They Delivered? Northern Times (2/2)Quest NewspapersNo ratings yet

- Consti Cases For Digest (16 To 30)Document148 pagesConsti Cases For Digest (16 To 30)Joel TabiraraNo ratings yet

- Law Enforcement Letters Opposing Asset Forfeiture Reform in ArizonaDocument3 pagesLaw Enforcement Letters Opposing Asset Forfeiture Reform in ArizonaTenth Amendment Center100% (1)

- Canon 9 "A Lawyer Shall Not, Directly or Indirectly, Assist in The Unauthorized Practice of LawDocument4 pagesCanon 9 "A Lawyer Shall Not, Directly or Indirectly, Assist in The Unauthorized Practice of LawKhim VentosaNo ratings yet

- Complaint - Criminal - 1 - Rittenhouse, Kyle H 2020CF000983 Rittenhouse, Kyle H. - 3753097 - 1 PDFDocument5 pagesComplaint - Criminal - 1 - Rittenhouse, Kyle H 2020CF000983 Rittenhouse, Kyle H. - 3753097 - 1 PDFTMJ4 News100% (2)

- DELA CERNA - Case Brief Bermudez v. Exec Sec TorresDocument2 pagesDELA CERNA - Case Brief Bermudez v. Exec Sec TorresHannah Keziah Dela CernaNo ratings yet

- First Ses - Art 2176 To 2194Document16 pagesFirst Ses - Art 2176 To 2194Bianca Viel Tombo CaligaganNo ratings yet

- Post NegoDocument46 pagesPost NegodreaNo ratings yet

- KrypticDocument5 pagesKryptickavirajNo ratings yet

- "Putang Ina Mo": The Case of People vs. Cho Nam Hyun For Grave Oral DefamationDocument6 pages"Putang Ina Mo": The Case of People vs. Cho Nam Hyun For Grave Oral DefamationJudge Eliza B. Yu100% (3)

- Trial of Shama Charan PalDocument288 pagesTrial of Shama Charan PalSampath BulusuNo ratings yet

- Up Political Law Reviewer 2017 PDFDocument411 pagesUp Political Law Reviewer 2017 PDFManny Aragones94% (16)