Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wallace v. Ideavillage - Order Granting MSJ

Uploaded by

Sarah Burstein0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views10 pagesWallace v. Ideavillage - Order Granting MSJ

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentWallace v. Ideavillage - Order Granting MSJ

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views10 pagesWallace v. Ideavillage - Order Granting MSJ

Uploaded by

Sarah BursteinWallace v. Ideavillage - Order Granting MSJ

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 10

NOT FOR PUBLICATION

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY

ALLISON WALLACE,

Plaintiff,

v.

IDEA VILLAGE PRODUCTS

CORPORATION,

Defendant.

DICKSON, U.S.M.J.

Civil Action No.: 06-cv-5673-JAD

OPINION

This matter comes before the Court upon Defendant Ideavillage Products Corpo tion's

("Ideavillage") motion for summary judgment (D.E. No. 61). The Court has reviewed the ar

raised by the parties in their briefs and at its hearing on this motion on July 15, 2014. Upon areful

consideration, and for the reasons set forth below, Defendant's motion for summary jud

GRANTED.

I. BACKGROUND

1

Plaintiff, Allison Wallace, is the named inventor of United States Design Patent No. D

(''the '990 patent") for the ornamental design of a ''body washing brush." (Defendant's L. Civ. . 56.1

Statement of Material Facts ("Def.'s 56.1"), D.E. No. 61-2, 2). The '990 patent was filed on M

2003 and was issued on February 3, 2004. (Id.) Defendant is the assignee of United States esign

1

The facts in this section are drawn from the Parties submissions pursuant to Local Civil Ru1e 56.1. Unles

otherwise indicated, the facts are not in dispute.

1

Patent No. D550, 914 ("the '914 patent") for the ornamental design of a "hand held cleaning nit."

2

(Declaration of Jason M. Drangel ("Drangel Decl."), D.E. No. 16-1, 7; Def.'s 56.1, D.E. No. 61- , 3).

The '914 patent was filed on March 6, 2006 and was issued on September 11, 2007. (Def.'s 56. , D.E.

No. 61-2, 3). The subject of this action is Defendant's Spin Spa Product (the "IV Product") which

was covered by the '914 patent. (See Def.'s 56.1, D.E. No. 61-2, 1, 3).

On November 27, 2006, Plaintiff, acting pro se, initiated the instant action against De

accusing Defendant's Spin Spa Product of infringing her body washing brush design in the '990 atent.

(See Complaint ("Compl."), D.E. No. 1 ).

II. LEGAL STANDARD

A. Summary Judgment

Summary judgment is appropriate "if the movant shows that there is no genuine dispute a to any

material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter oflaw." Fed. R. Civ. P. 56( a).

material if it "might affect the outcome of the suit under the governing law." Anderson v. Liberty

Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248 (1986). And a "genuine" issue of material fact exists for trial "if the evi

such that a reasonable jury could return a verdict for the nonmoving party." !d. The movant b s the

initial burden of establishing that no genuine issue of material fact exists. Celotex Corp. v. Cat

U.S. 317, 323 (1986). Where the non-moving party bears the burden of proof at trial, the movi

may discharge its burden by showing "that there is an absence of evidence to support the no

party's case." !d. at 325. If the movant meets this burden, the non-movant must then set forth

facts that demonstrate the existence of a genuine issue for trial. !d. at 324; see also Azur v. Chas Bank,

USA, Nat'/ Ass 'n, 601 F.3d 212, 216 (3d Cir. 2010). Notably, the "evidence of the non-movant s to be

2

Plaintiff alleges "no knowledge of this [fact] and the document speaks for itself." (Plaintiff's Res

Defendant's R. 56.1 Statement of Material Facts and Plaintiff's Supplemental Statement of Disputed

Facts ("Pl.'s 56.1"), D.E. No. 63-1, 3). The '914 patent named Ideavillage as the patent assignee.

Def's 56.1, D.E. No. 61-5). Therefore, the Court found Defendant to be the owner of the '914 patent.

2

nse to

aterial

x. 2 to

and all justifiable inferences are to be drawn in his favor." Anderson, 477 U.S. at 255.

non-moving party "must do more than simply show that there is some metaphysical doubt

material facts." Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp., 475 U.S. 574, 586 (1986);

Swain v. City of 457 F. 107, 109 (3d Cir. 2012) (stating that the non-moving p must

support its claim "by more than a mere scintilla of evidence").

B. Design Patent

Inventors with a "new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture" rna

a design patent. 35 U.S.C. 17l(a) (2012). Design patents are fundamentally different fro

patents because "[ u ]tility patents afford protection for the mechanical structure and functio

invention whereas design patent protection concerns the ornamental or aesthetic features of a

Carman Industries, Inc. v. Wahl, 724 F.2d 932, 939 n.l3 (Fed. Cir. 1983). Pursuant to 35 U.S.

(b), provisions relating to utility patents "shall apply to patents for designs, unless otherwise pro ided."

Thus, as with utility patents, "whoever without authority makes, uses, offers to sell, or sells any

invention, within the United States or imports into the United States any patented invention d g the

term of the patent therefor, infringes the patent." 35 U.S.C. 271(c).

To determine if an accused object infringes a design patent, courts apply the following an sts:

In some instances, the claimed design and the accused design will be sufficiently

distinct that it will be clear without more that the patentee has not met its burden

of proving the two designs would appear "substantially the same" to the ordinary

observer . . . . In other instances, when the claimed and accused designs are not

plainly dissimilar, resolution of the question whether the ordinary observer would

consider the two designs to be substantially the same will benefit from a

comparison of the claimed and accused design with the prior art.

Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665, 678 (Fed. Cir. 2008). "In other words, t

two levels to the infringement analysis: a level-one or 'threshold' analysis to determine if comp

the prior art is even necessary, and a second level analysis that accounts for prior art in less

3

cases." Wing Shing Prods. (BVJ) Co. v. Sunbeam Prods, Inc., 665 F. Supp. 2d 357, 362 (S.D.N.

affd, 374 F. App'x 956 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

For the second-level analysis, the test is "whether an ordinary observer, familiar with t prior

art, would be deceived into thinking that the accused design was the same as the patented d

namely, the "ordinary observer test." Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 672. Since "differences

the claimed and accused designs ... might not be noticeable in the abstract," the background

"provides ... a frame of reference" and "highlight[ s] the distinctions between the claimed design d the

accused design." !d. at 677-678. While examining the novel features of the claimed design r

"an important component of the comparison" in analyzing infringement claims, the ordinary

test established in Egyptian Goddess does not allow "assigning exaggerated importance t

differences between the claimed and accused designs relating to an insignificant feature simply ecause

that feature can be characterized as a point of novelty."

3

!d. at 677. Instead, "[a]n ordinary o server,

comparing the claimed and accused designs in light of the prior art, will attach importance to di rences

between the claimed design and the prior art depending on the overall effect of those difference on the

design." !d.

Finally, the "ordinary observer" test is "designed solely as a test of infringement" and " not a

test for determining validity." !d. at 678. Therefore, "the patentee bears the ultimate burden of

demonstrate infringement by a preponderance of evidence," whereas the accused infringer be "the

burden of production of ... prior art" on which the accused infringer elects to rely. !d. at 678-79.

3

Prior to Egyptian Goddess, the Federal Circuit applied a separate "point of novelty" test from the rdinary

observer test and "require[ d] the patentee to point out the point of novelty in the claimed design that s been

appropriated by the accused design." 543 F.3d at 676. However, a "point of novelty" test imposes probl when

multiple points of novelty are identified and the accused of design "does not copy all of the points of nove y, even

though it may copy most of them and even though it may give the overall appearance of being identi to the

claimed design." Id. at 677. Moreover, application of a "point of novelty" test may draw the court's art tion on

"nettlesome and ultimately distracting issues as whether a new combination of old design features could c nstitute

one or more 'points of novelty'." Wing Shing Prods. Co., 665 F. Supp. 2d. at 361.

4

III. DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

As a threshold matter, Plaintiff owns a design patent, not a utility patent. U.S. Design Pat t No.

D485,990 (filed Mar. 17, 2003). Therefore, the scope of the protection offered by her patent cov

the novel ornamental features of the "Body Washing Brush" as depicted in the '990 patent.

does not have any ownership right to the functional nature of the "Body Washing Brush."

The Federal Circuit strongly discourages the construction of a design patent through a tailed

verbal description of the claimed design, since "a design is better presented by an illustration

could be by any description and a description would probably not be intelligible without the illust

Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 679 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). Although

courts may find it "helpful to point out ... various features of the claimed design as they relat

accused design and the prior art," and courts may still exercise their discretion regarding the

detail in verbal description, the general rule is that "the illustration in the drawing views is its o

description." See id. at 679-680. Following Egyptian Goddess, courts have generally relied o

drawings to construe design claims. See, e.g., Richardson v. Stanley Works, Inc., 597 F.3d 128 (Fed.

Cir. 2010); Blackberry Limited v. Typo Products LLC, No. 14-cv-00023 (WHO), 2014 WL 1 18689

(N.D. Cal. Mar. 28, 2014); Wing Shing Prods. Co., 666 F. Supp. 2d 357. For the foregoing reas s, this

Court will conduct the analysis based on illustrations.

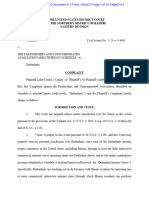

A. Level One: Side-by-Side Analysis

Defendant argues that the claimed design and the accused design are plainly dissimilar ithout

consulting any prior art. (Defendant's Brief in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment ("Def. s Mot.

Br."), D.E. No. 61-1, at 13-14). Plaintiff argues that the claimed design and the accused product re not

sufficiently distinct. (Plaintiff's Brief in Opposition to Defendant's Motion for Summary Ju gment

("Pl.'s Opp'n. Br."), D.E. No. 63, at 5). The two designs are presented below:

5

Plaintiff's '990 patent

(a " . -- --..ll

l '41 .. .

IV Product

Defendant points out six differences between the two designs:

4

1) '990 patent has a traight

handle, while the IV Product has a bent or curved handle; 2) '990 patent has a finger grip with a n and

valley design, while IV Product has no such finger grip; 3) '990 patent has a flat threaded open at the

base of the handle, while IV Product has a closed pointed end with an aperture where a rope can be

attached; 4) '990 patent has a round head with a two tiered brush, while IV product has an oblo g head

without a two tier brush; 5). '990 patent has .a protrusion at the back of the head, while IV Prod t has a

smooth back without any protrusion; and finally, 6). '990 patent has no decoration at the hac

handle, while IV product has an oval at the neck of the handle and an oval grip in the back of the andle.

(ld. at 15-20). In response, Plaintiff argues that "the differences . . Defendant pro

inconsequential to the overall designs" and that there are "striking similarities between the two d igns."

(Pl.'s Opp'n Br., D.E. No. 63, at 6).

Defendant also argues that the claimed design is a shower attachment with a hollow housing, where "t

the handle is designed to receive a hose or a water source." (Def.'s Mot. Br., D.. No. 61-1, at 14). In

the accused product is a battery operated brush with "sealed housing and the end of the handle cannot be

to a hose or water source". (ld.) The Court finds that the difference, although plain and apparent, con

of the product, therefore, is not within the scope of the design patent protection.

6

Pursuant to the teaching of Egyptian Goddess, District Courts have granted summary ju gment

based solely on comparison between accused and patented designs, without referring to prior a . See,

e.g., Voltstar Technologies, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., No. 13 C 5570, 2014 WL 3725860, at *2- (N.D.

Ill. Jul. 28, 2014); Sofpool LLC v. Kmart Corp., No. S-10-3333 (LKK), 2013 WL 2384331, at* (E.D.

Cal. May 30, 2013); Minka Lighting, Inc. v. Maxim Lighting Int'l, Inc., No. 06--cv-995, 20 9 WL

691594, at *7 (N.D. Tex. Mar. 16, 2009); Rainworks Ltd. v. Mill-Rose Co., 622 F. Supp. 2d 6 0, 656

(N.D. Ohio 2009); HR U.S. LLC v. Mizco Int'l, Inc., No. CV-07-2394, 2009 WL 890550, t *13

(E.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2009). Here, the Court acknowledges manifest differences in the overall app arance

of '990 patent and the IV product. Indeed, a comparison supports a finding that these two des s are

sufficiently distinct and Ms. Wallace cannot, as a matter of law, prove that the designs appear

substantially the same. To the ordinary observer, in other words, the two designs do n t look

substantially the same.

B. Level Two: Prior Art Comparisons

In an effort to assure a fair and complete decision on this record, the Court will take the rther

step, also taught by Egyptian Goddess, of comparing the accused and claimed design with the p 'or art.

See 543 F.3d. at 676. Ms. Wallace initiated this matter without an attorney. For various pr edural

reasons, the case was delayed. In 2011, this Court concluded Ms. Wallace, a pro se plaintiff, w uld be

better served by the sua sponte appointment of counsel. The parties have appeared for several se

conferences and counsel for both parties have patiently and with appropriate diligence, litiga

matter. Accordingly, I have concluded that the second level of analysis is appropriate and nece

clarify and fully explicate the Court's findings and conclusions. Therefore, we move to the le el-two

analysis.

7

As pointed out by Defendant, "the general concept of a brush with a handle is co in

numerous expired patents" (Def.'s Mot. Br., D.E. No. 61-1, at 2). The Court fmds that, si ce the

marketplace for brushes with handles is rather crowded, the spirit of Egyptian Goddess will b better

served by introducing prior art into the analysis. See 543 F.3d. at 676-77 ("[l]t can be difficult to

the question whether one thing is like another without being given a frame of reference."). s is

especially true when "a field is crowded with many references relating to the design .... " Id. at

Wing Shing Prods. Co., 665 F. Supp. 2d at 363 ("[l]n a cluttered world of the drip-coffeem

seems senseless to attempt to determine whether the ordinary observer would confuse two

without looking to the prior art for a point of reference."); Fanimation, Inc. v. Dan's Fan City, l .. No.

08-cv-1 071, 2010 WL 5285304, at *3 (S.D. Ind. Dec. 16, 2010) ("[T]he need to review pri

especially acute where, as here, the prior art is fairly robust.").

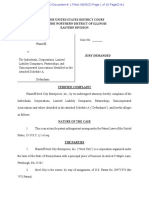

Defendant set forth over 170 patents as examples of prior art, and identified eight of the in its

brief in support of motion for summary judgment. (Transcript of July 15, 2014 Proceeding(' ul. 15

Tr."), D.E. No. 66, at 19, 2; Def.'s Mot. Br., D.E. No. 61-1, at 21-24, 31). The primary prior rt is a

utility patent-United States Patent No. 4,417,826 ("the '826 Patent''). (Jd. at 21-24). The '82 Patent

was issued in 1983 and was entitled "Liquid Driven Rotary Brush With Liquid Soap Feeder". S. No.

4,417,826 (tiled Dec. 24, 1981). The '826 patent (the prior art), the '990 patent (Plaintiff's pat t) and

the IV Product (the accused design) are shown below:

'826 Patent PJain.tiff's '990 Patent

.

8

Plaintift's '990 Patent significant similarities with the design of the '826 Patent. ong

other things, each design has a rounded head and a straight handle with "hill and valley" fing grip.

Each design has a round protrusion on the backside of the munded head.

Egyptian Goddess nbolished the element-by-clement analysis. See 543 F .3d. at 671 . lnst d . the

new analysis exnmines the design as a whole by requiring the fact-finders to "attach impo

differences between the claimed design and the prior art depending on the nverall effect u

difl'erences on the design." 543 F.3d. at 677 (emphasis added). The claimed design here is s gly

similar to the prior art, specifically the ' l!26 patent. "And when the claimed design is close to

art designs, small ditl'erences between the accused design and the claimed design are like!

important to the eye of the hypothetical ordinary observer." Id. at 676. The similarities bctw the

' 990 claimed patent and lhe '826 prior art patent are remarkable. Those similarities highli ht lhe

difference between the claimed potent and defendant's '914 patent, or IV product.

9

In light of the similarities between the '826 patent and the '990 patent, the Court conclu s that

no reasonable ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art, would be deceived into believing he IV

Product is the same as the design depicted in the '990 patent.

IV. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, Idealvillage Products Corporation's Motion for Summary Ju gment

(D.E. No. 61) is GRANTED. An appropriate form of Order accompanies this opinion.

10

You might also like

- Kyjen v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-15119) - Motion To StrikeDocument3 pagesKyjen v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-15119) - Motion To StrikeSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- AJ's Nifty Prods. v. Schedule A (23-cv-14200) - PI Opp'nDocument12 pagesAJ's Nifty Prods. v. Schedule A (23-cv-14200) - PI Opp'nSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Viniello v. Target - ComplaintDocument62 pagesViniello v. Target - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Blue Spring v. Schedule A - ComplaintDocument28 pagesBlue Spring v. Schedule A - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- UATP v. Kangaroo - Brief ISO PIDocument91 pagesUATP v. Kangaroo - Brief ISO PISarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Wang v. Schedule A - TRO BriefDocument33 pagesWang v. Schedule A - TRO BriefSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Keller v. Spirit Halloween - ComplaintDocument17 pagesKeller v. Spirit Halloween - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Smarttrend v. Optiluxx - Renewed Motion For JMOLDocument34 pagesSmarttrend v. Optiluxx - Renewed Motion For JMOLSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Rockbros v. Shehadeh - ComplaintDocument11 pagesRockbros v. Shehadeh - ComplaintSarah Burstein100% (1)

- ABC v. Schedule A (23-cv-04131) - Order On Preliminary Injunction (Ending Asset Freeze)Document12 pagesABC v. Schedule A (23-cv-04131) - Order On Preliminary Injunction (Ending Asset Freeze)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- XYZ (Pickle Jar) v. Schedule A - Order Denying MTD As MootDocument2 pagesXYZ (Pickle Jar) v. Schedule A - Order Denying MTD As MootSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Chrome Hearts - Motion For TRODocument17 pagesChrome Hearts - Motion For TROSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Combs v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-14485) - ComplaintDocument99 pagesCombs v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-14485) - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- TOB (1:23-cv-01563) - Motion To DissolveDocument20 pagesTOB (1:23-cv-01563) - Motion To DissolveSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Roblox v. Schedule A - Order Sanctioning PlaintiffDocument5 pagesRoblox v. Schedule A - Order Sanctioning PlaintiffSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Cixi City v. Yita - ComplaintDocument23 pagesCixi City v. Yita - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Wearable Shoe Tree v. Schedule A - Hefei XunTi OppositionDocument20 pagesWearable Shoe Tree v. Schedule A - Hefei XunTi OppositionSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Betty's Best v. Schedule A - RNR Re PIDocument21 pagesBetty's Best v. Schedule A - RNR Re PISarah Burstein100% (1)

- Sport Dimension v. Schedule A - Webelar MTDDocument28 pagesSport Dimension v. Schedule A - Webelar MTDSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Thousand Oaks Barrel v. Schedule A (EDVA) - UP ComplaintDocument57 pagesThousand Oaks Barrel v. Schedule A (EDVA) - UP ComplaintSarah Burstein100% (1)

- Thousand Oaks Barrel v. Schedule A (EDVA) - DP & UP ComplaintDocument32 pagesThousand Oaks Barrel v. Schedule A (EDVA) - DP & UP ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Hong Kong Xingtai v. Schedule A - Memo Re JoinderDocument5 pagesHong Kong Xingtai v. Schedule A - Memo Re JoinderSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Kohler v. Signature - ComplaintDocument27 pagesKohler v. Signature - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- BTL v. Schedule A - Exhibit 11 To PI Opposition (132-11)Document4 pagesBTL v. Schedule A - Exhibit 11 To PI Opposition (132-11)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Mobile Pixels v. Schedule A - Complaint (D. Mass.)Document156 pagesMobile Pixels v. Schedule A - Complaint (D. Mass.)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- BB v. Schedule A - ComplaintDocument28 pagesBB v. Schedule A - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Steel City v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-06993) - ComplaintDocument10 pagesSteel City v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-06993) - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Wright v. Dorsey - ResponsesDocument94 pagesWright v. Dorsey - ResponsesSarah Burstein100% (1)

- Pim v. Haribo - Decision (3d. Circuit)Document11 pagesPim v. Haribo - Decision (3d. Circuit)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Ridge v. Kirk - ComplaintDocument210 pagesRidge v. Kirk - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- La Complementariedad en La ParejaDocument9 pagesLa Complementariedad en La ParejaAbraham MoralesNo ratings yet

- Synopsis IPRDocument5 pagesSynopsis IPRashwaniNo ratings yet

- Sk39 Plaintiff RmlnluDocument33 pagesSk39 Plaintiff RmlnluChirag AhluwaliaNo ratings yet

- Provisional Application For Patent - BrochureDocument2 pagesProvisional Application For Patent - BrochureJames LindonNo ratings yet

- How To Take Patent in INDIA FinalDocument19 pagesHow To Take Patent in INDIA FinalnonsenseatulNo ratings yet

- PatentDocument19 pagesPatentAshutosh Singh Parmar100% (1)

- Civils Des Auteurs, Artistes Et Inventeurs, Published in 1846Document3 pagesCivils Des Auteurs, Artistes Et Inventeurs, Published in 1846ainihanifiahNo ratings yet

- Patent in IndiaDocument22 pagesPatent in IndianonsenseatulNo ratings yet

- Intellectual PropertyDocument3 pagesIntellectual PropertyAsma AzamNo ratings yet

- Alcalde Why Would You Marry A SerranaDocument24 pagesAlcalde Why Would You Marry A SerranaJulio VillaNo ratings yet

- RoyaltiesDocument4 pagesRoyaltiesDexter LedesmaNo ratings yet

- A Study of The Zoot Suit Culture Past and PresentDocument83 pagesA Study of The Zoot Suit Culture Past and Presenthudson1963No ratings yet

- Global Patent SourcesDocument288 pagesGlobal Patent SourcesBruno MenezesNo ratings yet

- MMS Ipr NotesDocument8 pagesMMS Ipr NotesTANVINo ratings yet

- Biotechnology I Notes Intellectual Property.Document2 pagesBiotechnology I Notes Intellectual Property.André BrincatNo ratings yet

- Ipr SyllabusDocument3 pagesIpr SyllabusArman Rocky100% (1)

- Mecanica de Fluidos Cap. 2 - WhiteDocument108 pagesMecanica de Fluidos Cap. 2 - WhiteZandrik ArismendiNo ratings yet

- Quality Management in Systems DevelopmentDocument35 pagesQuality Management in Systems Developmentalli14No ratings yet

- IP Law SlidesDocument450 pagesIP Law SlidesSmochiNo ratings yet

- E. E.' " (75 Ion Agent of Firm Rope-Mckay & AssociatesDocument7 pagesE. E.' " (75 Ion Agent of Firm Rope-Mckay & AssociatesVinh Do ThanhNo ratings yet

- Resume Koji Noguchi As of 20140608resume - Koji NoguchiDocument1 pageResume Koji Noguchi As of 20140608resume - Koji NoguchiKoji NoguchiNo ratings yet

- SUBJECT: Intellectual Property Rights: Sanjeev Kumar Dr. S.C. RoyDocument23 pagesSUBJECT: Intellectual Property Rights: Sanjeev Kumar Dr. S.C. RoyAnonymous IDhChBNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Property RightsDocument5 pagesIntellectual Property RightsMaggie Wa MaguNo ratings yet

- Competion Law and IPRDocument3 pagesCompetion Law and IPRKevin JosephNo ratings yet

- 1.two Greek Aristotelian Commentators On The Intellect-Final and Complete PDFDocument180 pages1.two Greek Aristotelian Commentators On The Intellect-Final and Complete PDFJessica Radin100% (1)

- Circle of FifthsDocument6 pagesCircle of Fifthstipo0011No ratings yet

- Intellectual Property Research PaperDocument5 pagesIntellectual Property Research PaperPraygod ManaseNo ratings yet

- Cavitating Oil Hyperspace Energy GeneratorDocument33 pagesCavitating Oil Hyperspace Energy GeneratorTeodor CimpocaNo ratings yet

- EPO - Training Overview - 06 03 12-FinalDocument72 pagesEPO - Training Overview - 06 03 12-FinalJussara FerreiraNo ratings yet

- 10 United Features vs. Munsingwear (Consing)Document1 page10 United Features vs. Munsingwear (Consing)aspiringlawyer1234100% (1)