Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ai Qing in Talk of The Town

Uploaded by

newyorkerdotcom0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views2 pagesOriginal Title

Ai Qing in Talk of the Town

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views2 pagesAi Qing in Talk of The Town

Uploaded by

newyorkerdotcomCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

THE TALK OF THE TOWN

Notes and Comment

FRIEND who lives ina one-

room apartment off Columbus

‘One of the appealing features of my

apartment—perhaps the appealing fea-

ture—is a fireplace (with a handsome

wooden mantel), although my land-

lord instructed me never to make a fre

in it, lest I ignite the upper West Side.

T have obeyed. One day last winter

when it was very cold in my apart-

ment, it occurred to me that Con

Edison’s expensive electric heat was

perhaps moving in an uninterrupted

thermal pattern from private ownership

up the chimney to the public sector, so

T got down on all fours on the hearth

and peered up in search of a damper I

might close. I didn’t see any. I did see

alittle gray sky. I crumpled up a lot of

old newspapers and stuffed them into

the chimney to seal it. Getting to my

feet, I began to dust myself off, and

found that the grime and soot on my

face, hands, arms, shirt, pants, and

shoes would not dust off Te clung, as if

ive. It had lumps in it, and webby

some of it was cinders, and some

of it was blobs of oil. All’ of it was

black, Its main characteristic was the

way it adhered. I washed my hands

and face with soap, then Comet cleans

er, then Mr. Clean. The hands and

face came out O.K., but the sink

tured black, I tried scrubbing the

sink, but the gunk stuck to the serub

brush, except when I tried to scrub

something else, and then a lot of it

came off and stuck to that. A modicum

of cleanliness was finally achieved—

clothes went to the cleaners and the

Taundromat—and I forgot about the

fireplace until yesterday afternoon,

when T entered the apartment to find

that the crumpled newspapers that had

been in the chimney were now in var~

ious corners of the room and on the bed.

From the fireplace itself was extruding

what appeared to be a low mountain of

black voleanic ash, burying the hearth,

an adjacent rug, and most of the floor

beyond. AA thin layer of fallout had set~

ted on chairs, desk, bed, clothes,

tables, television, books, and lamp

shades. The black stuff contained small

chunks of brick and cement as well as

the familiar petrochemicals. I spent an

hour trying to clean up, using broom,

brush, dustpan, water, ‘sponge, mop,

Cornet, Me, Clean, bath towel, paper

towels, and an old shirt; results were

slim. (‘The mopping, for example, was

basically unsuccessful because once the

swabbed area dried there appeared on

the periphery a heavy black outline,

Tike a high-tide mark, Scrubbing at

that only moved the tide Tine some-

where else.) I gave up, went out, and

ran into the landlord on the stairs. He

was wild-eyed and covered with soot,

and was clutching a camera. All the

apartments were in the same condition

as mine, he explained in a trembling

voice. Men working on the tenement

next door—transforming it from a flea-

bag into fancy condominium—hadde-

rmolished not only the tenement’s chim-

nneys but our building’s chimneys as

well. The brick and concrete had de-

scended, like Santa Claus, thoroughly

cleaning all the chimneys on the way

down. “Pm going to sue!” he ex=

claimed. “D’m taking pictures of every

thing? L wished him well, and went

to the hardware store to check on late

developments in heavy-duty cleansers.

Visitors

WW Eni the honor of bing visited

the other day by Ai Qing, Wang

Meng, and Feng Yidai, of the Peo-

ple’s Republic of China. Ai Qing,

aged seventy, is one of China’s preémi=

nent poets and the vice-chairman of

the Chinese Writers? Association.

Wang Meng, forty-six, is a renowned

novelist and short-story writer and the

vice-chairman of the Peking branch of

the Writers? Association, Feng Yidai,

sixty-seven, is one of his country’s lead

ranslators of English-language

ure and the editor of the journal

Reading. All had recently arrived in the

United States for the first time, to lec~

ture here and there under the auspices

of this country’s International Com-

munication Agency, the International

Writing Program at the University of

Towa, and the Translation Center at

Columbia University. Feng Yidai is

28

fient in English, naturally, and he

volunteered to interpret for his cony

triots. Ai Qing speaks French, having

spent two years in Paris as a young

man, but no English. Wang Meng had

known no English until his arrival in

this country, a couple of months before

four get-together, but had become

surprisingly well acquainted with our

tongue. He has a way with languages.

During the late Bfties, when he began

twenty years of exile in the northwest-

ern region of Xinjiang, at times work-

ing as_a peasant in the fields, he mas-

tered Uighur and translated Uighur

writings into Han. Wang Meng told

te, in English, that when he ge tothe

Towa campus, his first stop here, the

only English he had command of was

“Bye-bye” and “O.K.” He added, “Tt

you ty, God will help you.” Feng

Yidai laughed, and told Ai Qing what

Wang Meng had said, and then Ai

Qing laughed. “Don’t make fun with

me,” said Wang Meng, smiling.

‘Wang Meng and Feng Yidai were

in Western clothes. Ai Qing, every

inch the Oriental elder, was wearing,

Chinese cloth shoes and 2 Chinese

suit. We asked the poet what the ac-

ceptable term was these days, with the

Gang of Four on trial, for a jacket like

his—what we Americans had got used

‘a Mao jacket.

All smiles vanished. “This was

never a Mao jacket,” Ai Qing said

after a reflective pause. “Tam wearing.

what has always been a Dr. Sun Yate

sen jacket.”

Leaving that for revisionist histo-

rians to grapple with, we inguired into

the state of Western letters in China

today.

“helped translate Herman Wouk’s

You might also like

- Routh Release of InfoDocument5 pagesRouth Release of InfonewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- Ai Qing Talk of The TownDocument2 pagesAi Qing Talk of The TownnewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- 5 - 1st Air Cavalry Brigade AR 15-6 InvestigationDocument12 pages5 - 1st Air Cavalry Brigade AR 15-6 InvestigationFuManchu_vPeterSellersNo ratings yet

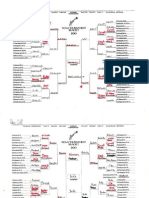

- Marked-Up New Yorker BracketsDocument10 pagesMarked-Up New Yorker BracketsnewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- Haiti's Declaration of IndependenceDocument9 pagesHaiti's Declaration of IndependencenewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- Centcom FOIADocument43 pagesCentcom FOIAZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- New Yorker NCAA BracketsDocument6 pagesNew Yorker NCAA BracketsnewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- New Yorker NCAA BracketsDocument6 pagesNew Yorker NCAA BracketsnewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- Richard Brody's Oscar Predictions vs. ResultsDocument1 pageRichard Brody's Oscar Predictions vs. ResultsnewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- New Yorker NCAA BracketsDocument6 pagesNew Yorker NCAA BracketsnewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- New Yorker NCAA BracketsDocument6 pagesNew Yorker NCAA BracketsnewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- RD STDocument2 pagesRD STnewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- Richard Brody's Oscar PredictionsDocument1 pageRichard Brody's Oscar PredictionsnewyorkerdotcomNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)