Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial: African American Sailor Brochure

Uploaded by

Matthew EngCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial: African American Sailor Brochure

Uploaded by

Matthew EngCopyright:

Available Formats

Robert Smalls, Pilot

Robert Smalls was born into slavery on a South Carolina plantation

in 1839. During the beginning years of the Civil War, Smalls became

BLACKS

the pilot of CSS Planter, a 300-ton dispatch vessel operating out of

Charleston. Smalls and a small group of African Americans, including

his family, escaped on Planter just before dawn on May 13, 1862 while

its three white officers went ashore for the night. Smalls successfully

guided the ship past several Confederate forts in the harbor, including

Fort Sumter. He continued on under a white flag until the blockade

ship Onward found the escaped slaves near the Federal fleet. For his capture of the Confederate

in

vessel, Smalls received his freedom and $1,500 in prize money. He later became the captain of

the Planter in 1863, for which Smalls earned $150 dollars a month in pay. He is credited as the

bl u e j ack e ts

first African American to captain a U.S. Navy ship. After the war, Smalls served on the South

Carolina state legislature and later, the U.S. House of Representatives as a Republican. African Americans in the Civil War

Siah Carter, Contraband

Like many other African American slaves, Siah Carter sought

freedom and refuge in the Union Navy along the myriad waterways

of the southern interior. At the time he joined the Union Navy,

Carter was working at Shirley Plantation in Charles City, Virginia.

He became the first of eighteen slaves to escape from Shirley

Plantation in 1862. Twenty-two year old Carter fled down the

James River two months after the Battle of Hampton Roads, finding

USS Monitor laying at anchor. He enlisted aboard the ironclad as a

“first class boy,” serving as a coal heaver and cook’s assistant for the duration of the ship’s short

existence. Carter survived the sinking of the famed vessel in December 1862, going on to serve The Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial

on several other Union ships until the end of the war. He was discharged from the Union Navy in

May 1865 and returned to Shirley Plantation to wed former slave Eliza Tarrow. They eventually

settled in Bermuda Hundred, Virginia, and raised thirteen children. The Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial seeks to

disseminate information and activities concerning the

John Lawson, Landsman 150th anniversary of the Union and Confederate navies

during the American Civil War. The Civil War Navy

Born in Philadelphia into slavery, John Lawson entered the Union Navy

as a contraband sailor. During the Civil War, Lawson served as an Sesquicentennial is coordinated under the direction of the

ammunition handler on the berthing deck of USS Hartford, commanded by Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington, D.C.

the intrepid Admiral David Glasgow Farragut. During the Battle of Mobile

Bay in August 1864, Lawson refused to leave the fight as shells exploded

around his gun crew. Lawson himself was thrown against the bulkhead For more information on the

of the Hartford from a shell explosion, which killed or wounded all of his Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial,

6-man crew. Both of Lawson’s legs were seriously injured. He quickly visit the official blog at:

gained his composure and returned to his station, refusing treatment and

finishing the fierce battle. For his gallantry in action, Lawson received the

Congressional Medal of Honor. He became one of twelve sailors to receive www.civilwarnavy150.blogspot.com

such honor that day, and additionally one of eight African Americans to win the United States’

highest military honor during the American Civil War. Lawson left the Navy following the war

and earned a living as a huckster in Philadelphia. He died in 1919 at the age of 81.

Robert Blake, Contraband

Born into slavery in Virginia, Robert Blake escaped to freedom and

joined the Union Navy as a contraband sailor in 1862. He enlisted

in Port Royal, Virginia, and served on the gunboat USS Marblehead

as a steward during the Civil War. Operating along the Stono River

in Legareville, South Carolina, on December 25, 1863, Marblehead

engaged a Confederate howitzer on nearby John’s Island. With no

formal training in combat, Blake nonetheless rushed to the gun deck

of the Marblehead to assist his comrades. He assumed the duties of www.history.navy.mil

a powder boy who was killed by a Confederate shell, running powder boxes to gun loaders.

The enemy eventually abandoned its position, leaving its munitions behind. For his heroic www.hrnm.navy.mil

contributions, Blake received the Congressional Medal of Honor in April 1864.

Printing courtesy of Lockheed Martin

“The slaves must be with us or against us in the war.” Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles

A History of Service: The Contraband Question Proudly They Served

B I

Before the War

A

By the spring of 1862, Gideon Welles grew increasingly aware of the issue of arming the It is important to note why

African Americans served in the United States Navy in country’s “peculiar institution.” Southern slaves fled in large numbers toward Union lines African Americans flocked to

many capacities dating back to the American Revolution. in the first year of the war, consuming valuable supplies and food needed for the military. the Union Navy. Many served

Faced with discrimination and conflict at home, African Writing from his headquarters in Port Royal, South Carolina, Charles Francis Adams, Jr. because whites did not desire the

American sailors showed great distinction and dignity wrote to his father, “We have now some 7,000 master-less slaves within our line and in less conditions, pay, and discipline of

through every American conflict. Their honor and than two months we shall have nearer 70,000, and what are we to do with them?” Although sea service. Yet for many black

courage in the face of adversity stand as a testimony this was a bitter pill to swallow for the Army, the question of escaped slaves, or contrabands, men in the 1860s, opportunities

to the principles upon which American was founded. joining the Union Navy was easy for Welles to answer. Welles could not let them sit unused. at sea far exceeded any offered

During the American Civil War, however, the cause of Both Welles and Lincoln agreed on the enlistment of African American sailors who were on land. Black sailors chose

freedom and liberty brought their proud tradition of free in the North from the outset of the conflict, but concern grew to the nature of handling to cede personal freedoms

Naval service to the forefront. slaves running across Federal lines. Slaves began to appear on Union vessels as early as for the restrictions of military

In the years leading up to the American Civil War, Fort Sumter’s attack, joining ships along the coast and rivers from Charleston to the Potomac. service. Every challenge faced

African Americans were allowed to enlist in the United On the heels of Lincoln’s radical racial and social legislation, Welles decided to make by white men on Union ships

States Navy, although their numbers were restricted. decisive changes in the structure of the Navy. In December 1862, Welles approved the would be equaled by their black

Despite South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun’s enlistment of former slaves as “landsmen,” unskilled sailors with no naval experience. counterparts. Even with evidence

insistence to relegate blacks to food service rates, Landsmen became the most common rank in the Navy, regardless of race. Union Navy of racial prejudice aboard Union

the Navy continued to recruit blacks. Officials in commanders sometimes returned fugitives back to their owners, but for the most part kept naval vessels, the institution

Washington also attempted to maintain the status quo of the white-dominated sea service, keeping them aboard. By March 1862, Welles made it illegal to return them. Welles’ gamble paid off. remained egalitarian by 19th

African Americans at a steady 4-5% of the entire force throughout the middle 19th century. This order He understood that free and formerly enslaved African Americans could aid the war effort dramatically, century standards.

came upon the insistence of Secretary of the Navy Abel P. Upshur in 1842, promising “not more than especially on offensives along the Mississippi River. A sailor’s pay was the greatest measure of egalitarian practice.

one-twentieth part of the crew of any vessel” would be men of color. Notwithstanding recruitment Historian Steven J. Ramold sums up these sentiments perfectly in a 2004 interview with The Journal of African American Compared to the Union Army, wage directly reflected ability,

restrictions dating back to the post-Revolutionary period, African Americans always appeared on History: “From the Navy Department’s perspective, Civil War sailors were just men to be recruited trained, employed, not race. The Navy rewarded skill with pay increases, allowing

American Naval vessels. Blacks in blue jackets numbered roughly 4.2% of all enlisted in and discharged no matter what their background.” Both the average black sailor an opportunity to increase in rank from

1850 and 5.6% in 1860. occupationally and geographically, African American sailors ship’s boy to ordinary seaman much faster than an Army private’s

When the newly-installed Republican President Abraham Lincoln entered the White had more in common with their white counterparts than ascendency to a non-commissioned officer. Status was not preset

House in March 1861, he inherited more than forty years of heightened racial and regional African American soldiers serving in the Union Army. The or static. Rather, it was earned.

tension dating back to the Missouri Compromise. At the time he entered his presidency, existence of contrabands in the Union Navy caused very little The enlistment of African Americans changed the makeup of

approximately 4,000,000 of the United States population was African American, the majority attention from a general public who already looked down on the Union Navy, even if it often split public opinion. Any attempt

of whom resided in the South as slaves. Only 182,000 blacks in the southern states claimed sea service as a military profession. to block African Americans from entering the service halted,

themselves to be free men. If the Union should completely collapse, how would Lincoln While some historians characterize a landsmen’s job as one allowing them to swell the ranks. One estimate placed roughly

effectively deal with the question of using African Americans as potential soldiers and filled with “menial tasks” for “unskilled men,” the opportunity 16% of the total enlisted force as black. “Rather than restrict black

sailors? Should African American men be allowed to take up arms for the cause of liberty for former slaves to ascend in rank and pay was key. Any enlisted men to special units,” historian James Harrod posited,

and equality under the banner of a unified nation? A war between kindred brethren would restrictions at face value did not obstruct the rate of African the Navy “placed the races side by side in the same vessels as

touch everyone, North and South; black and white. Indeed, the dilemma grew larger as American enlistments. Quite often, the percentage of African they had before the war.” In all, approximately 185,000 African

eleven southern states seceded from the Union, forming the Confederate States of America. Americans holding “skilled” positions of rank in the Union Navy Americans served the Union cause during the Civil War. Over

As the United States entered into open conflict with the Confederacy, the Union Navy took (petty officers, cooks, stewards, firemen, seamen) mirrored that 20,000 African Americans served in the Union Navy alone. Some

its pre-war familiarity with black sailors to the next level. Recruitment numbers would reach of white sailors. African Americans made the conscientious sources place the number closer to 29,000. Such numbers are

heights never before seen in American naval history. choice to fight for their freedom regardless of conditions still debated today, mostly due to the Union Navy’s lack of a

they faced. “These African American sailors were needed,” standardized racial classification during the war.

A Call to Arms Ramold remarked in the closing arguments of his 2004 African Americans fought in every campaign and battle in

T

interview; “They were Americans who didn’t hesitate to the American Civil War, from the blockading squadrons of the

The outbreak of hostilities at Fort Sumter allowed the slow pre-war trickle of African fight for their country.” Atlantic and Gulf to the brown water tributaries of the southern

American enlistments before the war to steadily gain speed. The prospect of fresh, able- Union Naval officer Admiral David Dixon Porter offered states. Black women also played a role in the naval war, offering

bodied recruits enticed top officials in Washington, including Secretary of the Navy Gideon a sobering comment to Assistant Secretary Fox on his their services as nurses aboard the hospital ship USS Red Rover

Welles and his competent assistant, Gustavus Vasa Fox. personal opinions of contraband sailors working among on the Mississippi River. By war’s end, eight African American

An increase in the number of men in the Union Navy was warranted. Lincoln’s call for an additional their white counterparts on the Arkansas River in sailors won the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest

18,000 sailors to complement the 7,600 seasoned Navy veterans following Fort Sumter did little to meet the 1863. Porter declared black sailors “better than the military medal offered in the United States.

necessities of war. The Navy needed adequately manned crews for countless ships, which had been either white people here, who I look upon as brutes, and Restrictions to African American enlistment resumed when

newly constructed or acquired for wartime use. Union Naval officers reported as early as July 1861 that their half savages.” While others in the squadron were less the war ended in 1865, flowing into the socially and racially

ships were “undermanned, poorly repaired, and inadequately armed.” The role of Union sailors patrolling the enthusiastic about the idea of an increased presence troubled era of Jim Crow. African Americans still remained a

3,000 mile Southern Blockade outlined by the “Anaconda Plan” could prove to be a deciding factor in bringing of contrabands, Porter was progressive enough to fixture of the peacetime Navy in the thirty years after the war,

about an early end to the war. There was no possibility of formally training new recruits due to the immediate realize their value to take the fight to the enemy, averaging between 10 and 14% of the total enlisted force. The

need for the sailors, so the Navy chose to tap into a familiar resource. often in patriotic fashion. It was no surprise necessity of manpower and fresh recruits waned in the late

The pressure for Welles and Fox to satisfy the manpower issue in the early months of the war was instantly then that the influx of sailors on the western 19th century, as society turned a blind eye to continued service

answered with the enlistment of African Americans. The Union Navy expanded black enlistment, integrating offensive allowed officers and squadron of the African American sailor. It is the service and dedication

them with their white counterparts. African Americans were not officially allowed to join the Union Army. commanders like Porter to assist in combined during the greatest American crisis, however, that is ultimately

Welles waived the 5% monthly pre-war limit of African American enlistment established in 1839 because it Army-Navy forces against the Confederate remembered and honored today. Their honor, courage, and

attracted little attention from the outside world. Indeed, Welles mastered the delicate balance between manpower, bastion at Vicksburg, Mississippi, the last commitment provided the necessary stepping stones to the

necessity, and political assertiveness. Issues of necessity and political correctness reached fever pitch for the remaining obstacle to splitting the southern official desegregation of armed forces in 1948.

newly-installed Navy Secretary by the second year of the war, forcing him to make tough decisions that would states in half.

forever shape the face of the United States Navy.

You might also like

- Captains of the Civil War: A Chronicle of the Blue and the GrayFrom EverandCaptains of the Civil War: A Chronicle of the Blue and the GrayNo ratings yet

- Captains of the Civil War; a chronicle of the blue and the grayFrom EverandCaptains of the Civil War; a chronicle of the blue and the grayNo ratings yet

- Manila and Santiago: The New Steel Navy in the Spanish-American WarFrom EverandManila and Santiago: The New Steel Navy in the Spanish-American WarRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (4)

- Summary of Phil Keith & Tom Clavin's To the Uttermost Ends of the EarthFrom EverandSummary of Phil Keith & Tom Clavin's To the Uttermost Ends of the EarthNo ratings yet

- U.S. Marines in Action: Two Hundred Years of Guts and GloryFrom EverandU.S. Marines in Action: Two Hundred Years of Guts and GloryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights (National Book Award Finalist)From EverandThe Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights (National Book Award Finalist)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- A Special Valor: The U.S. Marines and the Pacific WarFrom EverandA Special Valor: The U.S. Marines and the Pacific WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Sea of Thunder: Four Commanders and the Last Great Naval Campaign 1941-1945From EverandSea of Thunder: Four Commanders and the Last Great Naval Campaign 1941-1945Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- Pirates, Privateers, and Rebel Raiders of the Carolina CoastFrom EverandPirates, Privateers, and Rebel Raiders of the Carolina CoastNo ratings yet

- From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil WarFrom EverandFrom Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Backdrop for the Star Spangled Banner: A Look at Some Key Events Leading up to the ‘Land of the Free & the Home of the Brave’From EverandBackdrop for the Star Spangled Banner: A Look at Some Key Events Leading up to the ‘Land of the Free & the Home of the Brave’No ratings yet

- Letters Home from the Brothertown "Boys"From EverandLetters Home from the Brothertown "Boys"Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ironclads and Big Guns of the Confederacy: The Journal and Letters of John M. BrookeFrom EverandIronclads and Big Guns of the Confederacy: The Journal and Letters of John M. BrookeGeorge M. Brooke, Jr.No ratings yet

- The Third Voyage: A World War Ii Voyage of the Libertyship Albert Gallatio & CrewFrom EverandThe Third Voyage: A World War Ii Voyage of the Libertyship Albert Gallatio & CrewNo ratings yet

- Captains of The Civil War A Chronicle of The Blue and The Gray by Wood, William (William Charles Henry), 1864-1947Document152 pagesCaptains of The Civil War A Chronicle of The Blue and The Gray by Wood, William (William Charles Henry), 1864-1947Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Sea Wolf of the Confederacy: The Daring Civil War Raids of Naval Lt. Charles W. ReadFrom EverandSea Wolf of the Confederacy: The Daring Civil War Raids of Naval Lt. Charles W. ReadRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Lowcountry Confederates: Rebels, Yankees, and South Carolina Rice Plantations: More Tales from BrookgreenFrom EverandLowcountry Confederates: Rebels, Yankees, and South Carolina Rice Plantations: More Tales from BrookgreenNo ratings yet

- Weird-but-True Facts about the U.S. MilitaryFrom EverandWeird-but-True Facts about the U.S. MilitaryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Military History Anniversaries 0201 Thru 021420Document93 pagesMilitary History Anniversaries 0201 Thru 021420DonnieNo ratings yet

- The Comanches: A History of White's Battalion, Virginia CavalryFrom EverandThe Comanches: A History of White's Battalion, Virginia CavalryNo ratings yet

- Shepherds of the Sea: Destroyer Escorts in World War IIFrom EverandShepherds of the Sea: Destroyer Escorts in World War IIRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Blockaders, Refugees, and Contrabands: Civil War on Florida's Gulf Coast, 1861-1865From EverandBlockaders, Refugees, and Contrabands: Civil War on Florida's Gulf Coast, 1861-1865No ratings yet

- Poltroons and Patriots: A Popular Account of the War of 1812, Vol. IIFrom EverandPoltroons and Patriots: A Popular Account of the War of 1812, Vol. IINo ratings yet

- The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter, 1813-1891From EverandThe Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter, 1813-1891No ratings yet

- Fremantle's Submarines: How Allied Submariners and Western Australians Helped to Win the War in the PacificFrom EverandFremantle's Submarines: How Allied Submariners and Western Australians Helped to Win the War in the PacificRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Sumter After the First Shots: The Untold Story of America's Most Famous Fort until the End of the Civil WarFrom EverandSumter After the First Shots: The Untold Story of America's Most Famous Fort until the End of the Civil WarNo ratings yet

- Undefeated: America's Heroic Fight for Bataan and CorregidorFrom EverandUndefeated: America's Heroic Fight for Bataan and CorregidorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- SURVIVOR: USS Russell a World War Two DestroyerFrom EverandSURVIVOR: USS Russell a World War Two DestroyerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- The Rebel Shore: The Story of Union Sea Power in the Civil WarFrom EverandThe Rebel Shore: The Story of Union Sea Power in the Civil WarNo ratings yet

- The Civil WarDocument10 pagesThe Civil WarViktoriia RybiakNo ratings yet

- Grand Army of The Republic (G.A.R.)Document1 pageGrand Army of The Republic (G.A.R.)DRoe100% (2)

- SAPS New Recruit Application DetailsDocument1 pageSAPS New Recruit Application DetailsJean Marie VianneyNo ratings yet

- Serenity Role Playing GameDocument234 pagesSerenity Role Playing GameRuben RosarioNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For War of 1812Document5 pagesThesis Statement For War of 1812aliciabrooksbeaumont100% (1)

- SM-31S Stiletto LF F125XX Taiwan Linecard 2020 MetricDocument2 pagesSM-31S Stiletto LF F125XX Taiwan Linecard 2020 MetricStavatti Aerospace LtdNo ratings yet

- Failure - of - The - Schleiffen - Plan HISTORYDocument9 pagesFailure - of - The - Schleiffen - Plan HISTORYSaja MahmoudNo ratings yet

- DCS Huey Helicopter GuideDocument95 pagesDCS Huey Helicopter GuideSam AelNo ratings yet

- Legions Imperialis Cards and Rules v4.pdf Version 1Document37 pagesLegions Imperialis Cards and Rules v4.pdf Version 1msdoxseeNo ratings yet

- Weapons - of.WWII - truePDF Fall.2015Document116 pagesWeapons - of.WWII - truePDF Fall.2015Ron Lebert100% (3)

- Weapon Delivery Analysis and Ballistic Flight Testing: Agard 10Document176 pagesWeapon Delivery Analysis and Ballistic Flight Testing: Agard 10BarisNo ratings yet

- Crochet Pattern: by Sabrina SomersDocument8 pagesCrochet Pattern: by Sabrina SomersYahaira Suarez Jimenez100% (2)

- War Making in NATO Strategic Culture Transformation of Modern Western StrategyDocument332 pagesWar Making in NATO Strategic Culture Transformation of Modern Western StrategyMatejNo ratings yet

- Tobril Special 0408Document16 pagesTobril Special 0408ikab01_6105537820% (1)

- Browning Date Your Firearm - Auto-5 Semi-Automatic ShotgunDocument4 pagesBrowning Date Your Firearm - Auto-5 Semi-Automatic Shotgundannyjan5080No ratings yet

- Afp History Organization-1Document22 pagesAfp History Organization-1Donna EvaristoNo ratings yet

- Tesla Howitzer and Scalar Weaponry - EarthquakesDocument8 pagesTesla Howitzer and Scalar Weaponry - Earthquakeslaws632100% (1)

- S52 Extraordinary BraveryDocument1 pageS52 Extraordinary BraveryWilly230104No ratings yet

- The essential first step for firearm safetyDocument30 pagesThe essential first step for firearm safetyJay AndrewsNo ratings yet

- Nationalism, Empire and Memory: The Connaught Rangers Mutiny of 1920Document5 pagesNationalism, Empire and Memory: The Connaught Rangers Mutiny of 1920James HeartfieldNo ratings yet

- Podesta Military Tribunal Day Three .Thursday 6 May 2021Document6 pagesPodesta Military Tribunal Day Three .Thursday 6 May 2021Ronald Wederfoort100% (3)

- 092hnr 304 Section 9 TranspositionDocument31 pages092hnr 304 Section 9 TranspositionMuh ElbinNo ratings yet

- 2023 Sterling KatalogDocument124 pages2023 Sterling KatalogBerkeNo ratings yet

- RPH #20 Last Filipino General To Surrender To The AmericaDocument2 pagesRPH #20 Last Filipino General To Surrender To The AmericaAngelJoy PerezNo ratings yet

- Japan - TamilDocument32 pagesJapan - Tamilraaz_chitraNo ratings yet

- The Interrelation of Wood Requirements of The Austrian Navy and The Shaping of The Cultural Landscape in The Northern Adriatic RegionDocument20 pagesThe Interrelation of Wood Requirements of The Austrian Navy and The Shaping of The Cultural Landscape in The Northern Adriatic RegionHrvojeNo ratings yet

- Battle Report - The Black Gate OpensDocument14 pagesBattle Report - The Black Gate OpensAnonymous tMbueXyNo ratings yet

- Nazi Germany Resource SampleDocument7 pagesNazi Germany Resource SampleIrram RanaNo ratings yet

- Kami Export - Louisiana Purchase LessonDocument5 pagesKami Export - Louisiana Purchase LessonDoggyGirl5554]No ratings yet

- Berman Blog - Eldar Dark ReapersDocument8 pagesBerman Blog - Eldar Dark ReapersJason BermanNo ratings yet

- UNMANNED SYSTEMS IN COMBAT MISSIONSDocument8 pagesUNMANNED SYSTEMS IN COMBAT MISSIONSElena JelerNo ratings yet

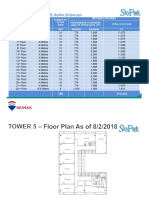

- Skypark Floor Plan (Tower 5 & Tower 6)Document17 pagesSkypark Floor Plan (Tower 5 & Tower 6)NURAIN HANIS BINTI ARIFFNo ratings yet