Professional Documents

Culture Documents

An Analysis of Huckleberry Finn

Uploaded by

Mateusz Buczko50%(2)50% found this document useful (2 votes)

764 views5 pagesHigh-school analysis of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as an indictment of 19th-century American society.

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHigh-school analysis of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as an indictment of 19th-century American society.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

50%(2)50% found this document useful (2 votes)

764 views5 pagesAn Analysis of Huckleberry Finn

Uploaded by

Mateusz BuczkoHigh-school analysis of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as an indictment of 19th-century American society.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

An Analysis of

Huckleberry Finn

by MATEUSZ BUCZKO

‘The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ is more than just the light-hearted

adventure story of a white boy and black slave as they journey down the

Mississipi River. If one penetrates this picaresque surface, one can see that the

story also contains a strong if subtle commentary on the society of the time, for

which Huck – in his words and actions, and through the characters he meets and

becomes mixed up with – serves as a medium. Throughout the text, we see

Huck struggle with these sort of people – one can clump them under the general

banner of ‘sivilization’ – as his own, natural conscience counters their views and

values. Thus, more than being just a picaresque novel a la Tom Sawyer, ‘The

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ presents us with a maturing boy single-

handedly dealing with and ultimately overcoming the hypocritical and corrupt

influences of human society.

One of Twain’s primary indictments in the text is false good-doing, as

exemplified in Passage One by Miss Watson and the Widow. For one thing,

good-doing is often hypocritical. The Widow does not allow Huck to smoke,

though Huck tells us that “she took snuff, too; of course that was all right,

because she done it herself.” However, it is Miss Watson in particular who

epitomises the negatives of good-doing. Though only having moved in, she

immediately takes responsibility for Huck’s learning and behaviour. He

complains, “She worked me middling hard for about an hour, then the widow

made her ease up.” This highlights the difference between Miss Watson and the

Widow – the Widow, though also a good-doing hindrance at times, does not

impose ‘sivilization’ onto Huck the way Miss Watson does. Whereas the former

is still sympathetic, the latter is too ruthless to deserve sympathy; in trying to

reform Huck into a model middle-class boy, she is a great and constant pain to

him: “Miss Watson she kept pecking at me, and it got tiresome and lonesome.”

Miss Watson’s good-doing is also selfish in a way, as she regards it as her

ticket to Heaven. When Huck says he wishes he was at the bad place, she tells

him “it was wicked to say what I said; said she wouldn’t say it for the whole

world; she was going to live so as to go to the good place.” It is as if her life of

proper behaviour and good-doing is simply an assurance for the right afterlife.

Furthermore, her moralizing preaching also runs against Huck’s practical

character. He sees the bad place as simply something different, and therefore

exciting and good - “All I wanted was to go somewheres; all I wanted was a

change, I warn’t particular.” Later he says “I couldn’t see no advantage in going

where she was going, so I made up my mind I wouldn’t try for it. But I never

said so, because it would only make trouble, and wouldn’t do no good.” Miss

Watson can’t understand Huck’s innocent, down-to-earth way of viewing her

ridiculous ‘good place – bad place’ system. For an adventurous child such as him,

her description of the good place sounds dreadful: “I didn’t think much of it. But

I never said so. I asked her if she reckoned Tom Sawyer would go there, and she

said no by a considerable sight. I was glad about that, because I wanted him and

me to be together.”

This shows another of Huck’s values, the value he places on friendship

above all else. As we have just seen, he is happy to go to the bad place so long as

his friend Tom Sawyer is there. A far more powerful and serious example is in

Passage 2, when – having to decide between dobbing in Jim and going to hell –

Huck thinks for a minute and then says to himself, “All right, then, I’ll go to

hell”, and tears up his letter to Miss Watson. He does not realize that, in both

instances, he is actually doing the right thing by opting to go to the bad place. In

the first instance, he is showing us his spirit of life and adventure, and his

eagerness to be with his friend. In the second instance, he is showing us that he

values Jim’s freedom more than he does his own in the afterlife. It is a reflection

of his kind and innocent spirit. In both instances, the good places actually

represent negatives of sivilization – good-doing in the first, and racism in the

second. By rejecting them, Huck is rejecting sivilization, as he does throughout

the entire novel.

We see Huck’s socially-implanted conscience at work at the beginning of

Passage 2. Huck, afraid of the consequences for his ‘sins’, decides to pray, “but

the words wouldn’t come”. He believes this is because he is “playing double. I

was letting on to give up sin, but away inside of me I was holding on to the

biggest one of all.” This ‘sin’, of course, is that he knows of a black slave’s escape

but has failed to dob him in. Of course, in choosing Jim’s freedom over his

chance of going to Heaven, Huck is showing the strength and purity of his

goodness. It is a victory of genuine humanity over the corrupted moral code,

created and maintained by ‘sivilization’, which it is replaced by in most human

beings over time.

Huck’s good, sympathetic humanity is also evident in Passage 3, where his

former companions – the degenerate duke and king – are tarred and feathered by

a mob after a performance of the Royal Nonesuch. Huck says “it made me sick

to see it; and I was sorry for them poor pitiful rascals, it seemed like I couldn’t

ever feel any hardness against them any more in the world.” He goes home

feeling “kind of ornery, and humble, and to blame, somehow – though I hadn’t

done nothing.” He is capable of feeling sympathy for the duke and the king

despite witnessing their degeneracy on multiple occasions, and being a victim of

their lies and selfishness himself. Indeed, he even goes beyond sympathy to

feeling guilty, simply because he did not warn the conmen about the mob’s plan

in time.

The final paragraph of Passage 3 is particularly interesting: “that’s always

the way; it don’t make no difference whether you do right or wrong, a person’s

conscience ain’t got no sense, and just goes for him anyway…It takes up more

room than all the rest of a person’s insides, and yet ain’t no good, nohow.” Huck

complains of this because his conscience is at ends with the views and values of

‘sivilization’. Because of the confusion and mixed feelings his conscience’s fight

with the socially-implanted socially-created moral code creates, he regards it as a

pain, though in reality it saves him from ever committing any real wrong-doing.

Were it not for his own true conscience, he would have – among other things –

sent that letter to Miss Watson in Passage 2, believing himself justified in doing so

despite sending a good man, who has done a great deal for him and loved him,

back into slavery. The fact is, though he considers himself a sinner because he

failed the social moral code, he is in fact the complete opposite – in listening to

his innately good heart, he has not fallen to the corruption that the rest of his

society has.

While the novel is structurally picaresque, this internal struggle in Huck

between his genuine goodness and his socially-implanted moral code adds a hint

of psychology to the novel. Numerous times we are given insights into Huck’s

thoughts and feelings, and often Twain uses these to imply a certain attitude

towards something. For example, after writing the letter to Miss Watson about

Jim, Huck says “I felt good and all washed clean of sin”. Of course, this feeling is

fake, because in fact Huck was not sinning at all by allowing Jim to keep his

freedom. But through this Twain is able to show that religion – of which ‘sin’ is

a major concept – is artificial, serving only to prop up the similarly artifical views

and values of society. He indicts religion many other times in the novel through

Huck – for example, when the Widow refuses to let Huck smoke, Huck

complains “Here she was a-bothering about Moses, which was no kin to her,

and no use to anybody, being gone, you see, yet finding a power of fault with me

for doing a thing that had some good in it.”

There is also the intense depression Huck experiences at the end of

Passage 1, which is of no direct consequence to the picaresque unfolding of

events. He talks of death and ghosts and a spider burning up in a candle, working

himself up into a state of great depression and fear. This seems to be the terrible

impact excessive ‘sivilizing’ has on Huck – after the Widow’s and Miss Watson’s

endless “pecking”, he feels wasted and empty and bad. It is the same feeling he

has after witnessing the duke and the king’s punishment at the hands of the mob;

he feels “kind of ornery, and humble, and to blame, somehow”. Though

physically tough and mentally smart, he has a very sensitive nature – among other

things, he hates being oppressed by ‘sivilization’, and hates to see others suffer –

even if they are unpleasant conmen.

‘The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’, though a wonderful and idyllic

adventure story, is a lot more than just that. It is a brilliant piece of satire,

criticizing – usually in comic disguise, but sometimes openly and emotionally –

the society which Huck is surrounded by on his journey down the river.

Whether it be do-gooding, religion or racism, Twain does not hesitate to expose

the faults within human society, and places his hero – Huckleberry Finn – at

odds with this mighty, degenerate force he calls ‘sivilization’. His hero is not a

great warrior, but a clever, rebellious boy, a boy who refuses to accept the ideals

that sivilization – for example in the form of Miss Watson – tries to impose on

him. The story is more than just a series of fun and exciting adventures – it shows

us the development of a good-hearted child growing up amid a callous,

hypocritical and immoral society, absorbing much of it but, in the end, always

staying true to his own innate goodness.

You might also like

- The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnDocument4 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry FinnNeeraj BhatejaNo ratings yet

- Transcendentalism in Huckleberry FinnDocument5 pagesTranscendentalism in Huckleberry FinnSafi UllahNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnDocument29 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry FinnArnab Sengupta100% (1)

- An Analysis of Huckleberry Finn by Mark TwainDocument5 pagesAn Analysis of Huckleberry Finn by Mark TwainUmar AlamNo ratings yet

- Huckleberry Finn Conflict Between The IndividualDocument2 pagesHuckleberry Finn Conflict Between The IndividualAnca Criveteanu100% (1)

- Deconstruction of Societal ValuesDocument3 pagesDeconstruction of Societal ValuesSafi UllahNo ratings yet

- Major Characters in The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnDocument11 pagesMajor Characters in The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnAnaMariaBostan100% (1)

- The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnDocument3 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry FinnMagali ProfInglesNo ratings yet

- Themes of HuckDocument7 pagesThemes of Huckgenang100% (1)

- The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnDocument8 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry FinnalinaNo ratings yet

- Huck Finn EssayDocument6 pagesHuck Finn EssayJeremy Keeshin100% (7)

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Essay PortfolioDocument4 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Essay Portfolioapi-457161876No ratings yet

- American Literary Realism and NaturalismDocument7 pagesAmerican Literary Realism and NaturalismMi Na100% (1)

- An Analysis of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Based On The Cosmogonic CycleDocument7 pagesAn Analysis of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Based On The Cosmogonic CycleAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Black, White, and Huckleberry Finn: Re-imagining the American DreamFrom EverandBlack, White, and Huckleberry Finn: Re-imagining the American DreamNo ratings yet

- How Huck Finn Critiques 19th Century American SouthDocument5 pagesHow Huck Finn Critiques 19th Century American SouthPrincess OclaritNo ratings yet

- Huckleberry Finn and Morality ReduxDocument15 pagesHuckleberry Finn and Morality ReduxMichael BoughnNo ratings yet

- Themes and Characterization in Huckleberry FinnDocument14 pagesThemes and Characterization in Huckleberry FinnAMBAR PATHAKNo ratings yet

- American TranscendentalismDocument2 pagesAmerican TranscendentalismKH WiltNo ratings yet

- PygmalionDocument3 pagesPygmalionapi-286751465No ratings yet

- Huck Finn Synthesis EssayDocument4 pagesHuck Finn Synthesis Essayapi-386412182No ratings yet

- Essay On Mrs Dalloway by Virginia WoolfDocument4 pagesEssay On Mrs Dalloway by Virginia WoolfHabes NoraNo ratings yet

- Huck Finn Manuscript FoundDocument29 pagesHuck Finn Manuscript FoundNoly Love NoleNo ratings yet

- Jim - The True Hero of Huck FinnDocument2 pagesJim - The True Hero of Huck FinnShirley LoNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn SummaryDocument3 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry Finn SummaryPaul.S.M.No ratings yet

- Picaresque-Huck FinnDocument13 pagesPicaresque-Huck Finnapi-234530951100% (1)

- Alice AnalysisDocument2 pagesAlice AnalysisHaryandoMuhammad100% (2)

- Thomas Hardy Philophy of LifeDocument8 pagesThomas Hardy Philophy of LifeRaheela KhanNo ratings yet

- PygmalionDocument5 pagesPygmalionHira Doll100% (2)

- "Young Goodman Brown" A Psychoanalytic ReadingDocument3 pages"Young Goodman Brown" A Psychoanalytic ReadingMariana Barbieri MantoanelliNo ratings yet

- Critical Statements About 'The Great Gatsby'Document7 pagesCritical Statements About 'The Great Gatsby'JhelReshel CubillanTelin II100% (1)

- Narrative Techniques in Postmodern English LiteratureDocument4 pagesNarrative Techniques in Postmodern English LiteratureМихаица Николае Дину0% (1)

- Compare and Contrast Essay - The Picture of Dorian GrayDocument10 pagesCompare and Contrast Essay - The Picture of Dorian GrayElisaZhangNo ratings yet

- Scarlet Letter Study GuideDocument5 pagesScarlet Letter Study GuideDavid Hankin100% (17)

- Class Notes English Lit Araby James JoyceDocument2 pagesClass Notes English Lit Araby James JoyceRodrigo Jappe0% (1)

- Beloved Research PaperDocument9 pagesBeloved Research PaperAmanda May Bunker100% (3)

- Hedonism and Aestheticism in Oscar WildeDocument2 pagesHedonism and Aestheticism in Oscar Wildealelab80No ratings yet

- American TranscendentalismDocument18 pagesAmerican Transcendentalismhatis100% (1)

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Chapters XXVIII - XXXDocument6 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Chapters XXVIII - XXXLanaNo ratings yet

- Foe Vs Robinson CrusoeDocument3 pagesFoe Vs Robinson CrusoefroggybreNo ratings yet

- Virginia Woolf's Stream of Consciousness in Mrs. DallowayDocument54 pagesVirginia Woolf's Stream of Consciousness in Mrs. DallowayVinícius BelvedereNo ratings yet

- Huckleberry Finn Novel Study GuideDocument8 pagesHuckleberry Finn Novel Study GuideHannah BoerckelNo ratings yet

- A Review of A Hunger ArtistDocument6 pagesA Review of A Hunger Artisthossein sharifi100% (2)

- Mrs DallowayDocument19 pagesMrs DallowayMiha Mihaela100% (1)

- The Elephant Vanishes AnalysisDocument3 pagesThe Elephant Vanishes AnalysisDavid100% (1)

- Unit-2 - Mrs. DallowayDocument52 pagesUnit-2 - Mrs. Dallowayprajjwal singhNo ratings yet

- The NecklaceDocument11 pagesThe NecklaceLeonard Ligutom100% (1)

- The Adventures of HUckleberry FInn. Project in EngDocument4 pagesThe Adventures of HUckleberry FInn. Project in EngSean Joshua CarilloNo ratings yet

- Analyze of PygmalionDocument28 pagesAnalyze of PygmalionVhe Vena S100% (2)

- House On Mango Street Essay - Ethnic LitDocument4 pagesHouse On Mango Street Essay - Ethnic LitChelce HesslerNo ratings yet

- Pride & Prejudice EssayDocument6 pagesPride & Prejudice Essaybmgphoto100% (1)

- Mark Twain and American Realism PaperDocument7 pagesMark Twain and American Realism Paperapi-235622086No ratings yet

- Pride and Prejudice CharactersDocument21 pagesPride and Prejudice CharactersMehdi KhademiNo ratings yet

- George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion and Caesar and CleopatraDocument4 pagesGeorge Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion and Caesar and CleopatraOlga CojocaruNo ratings yet

- Literary Criticism Table IIDocument7 pagesLiterary Criticism Table IIYarmantoNo ratings yet

- Young Goodman BrownDocument4 pagesYoung Goodman BrownSzilvia Eva Kiss100% (1)

- 14 An Outline of History of American LiteratureDocument47 pages14 An Outline of History of American LiteratureMalina CindeaNo ratings yet

- Lost Generation WritersDocument7 pagesLost Generation Writersapi-254814217100% (1)

- Tones, Moods & Irony in Chaucer's Canterbury TalesDocument4 pagesTones, Moods & Irony in Chaucer's Canterbury TalesSamantha BordadorNo ratings yet

- Huckleberry Finn - Society's Hypocrisy and the River's FreedomDocument5 pagesHuckleberry Finn - Society's Hypocrisy and the River's FreedomIrinaElenaŞincuNo ratings yet

- Polish Festival at Federation Square 2012Document2 pagesPolish Festival at Federation Square 2012Mateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- Edgar GambinDocument1 pageEdgar GambinMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- Putting Planning in The MediaDocument2 pagesPutting Planning in The MediaMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- Polish Festival at Federation Square 2011Document2 pagesPolish Festival at Federation Square 2011Mateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- The FoundationDocument15 pagesThe FoundationMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- National Rhododendron GardensDocument1 pageNational Rhododendron GardensMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

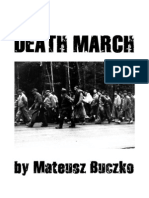

- Death MarchDocument11 pagesDeath MarchMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- Polish Festival at Federation Square 2011Document2 pagesPolish Festival at Federation Square 2011Mateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- Springtime Festivals in MelbourneDocument1 pageSpringtime Festivals in MelbourneMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- Polish Festival at Federation Square 2009Document3 pagesPolish Festival at Federation Square 2009Mateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- Edgar Gambin (Full Text)Document6 pagesEdgar Gambin (Full Text)Mateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- The Exorcist - An AnalysisDocument4 pagesThe Exorcist - An AnalysisMateusz Buczko0% (1)

- Olga BuczkoDocument2 pagesOlga BuczkoMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- Racialist Social DarwinismDocument5 pagesRacialist Social DarwinismMateusz Buczko100% (1)

- An Analysis of Franz KafkaDocument4 pagesAn Analysis of Franz KafkaMateusz Buczko0% (3)

- The Role of Print in The Rise of DemocracyDocument6 pagesThe Role of Print in The Rise of DemocracyMateusz Buczko100% (1)

- Television and Postmodern CultureDocument7 pagesTelevision and Postmodern CultureMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- The Prodigy - An AnalysisDocument2 pagesThe Prodigy - An AnalysisMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- This Is Your Life - Three Movies' Critique of Modern BanalityDocument7 pagesThis Is Your Life - Three Movies' Critique of Modern BanalityMateusz BuczkoNo ratings yet

- Huckleberry Finn Chapter by Chapter SummaryDocument8 pagesHuckleberry Finn Chapter by Chapter Summarywendyy100% (5)

- One Way ANOVADocument16 pagesOne Way ANOVAvisu0090% (1)

- 4Document23 pages4rdsf1425No ratings yet

- Fragments From American Literature: Henry James Realism and HumorDocument3 pagesFragments From American Literature: Henry James Realism and HumorFruzsee89No ratings yet

- Short Summary of The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnDocument3 pagesShort Summary of The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnFaharJavidNo ratings yet

- Reading 10.29Document6 pagesReading 10.29AbbyNo ratings yet

- Simone de Beauvoir's Existential Basis for SocialismDocument12 pagesSimone de Beauvoir's Existential Basis for SocialismMiltonNo ratings yet

- Mark Twain'S The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn As A Racist Novel: A StudyDocument12 pagesMark Twain'S The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn As A Racist Novel: A StudyTriviaNo ratings yet

- Huck Finn Study Guide Chapter SummariesDocument3 pagesHuck Finn Study Guide Chapter SummariesChristine SonNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Review Flashcards - QuizletDocument7 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Review Flashcards - QuizletKhatidja AllyNo ratings yet

- BYERLY - SILVERMAN Paradise UnderstoodDocument34 pagesBYERLY - SILVERMAN Paradise UnderstoodPierre Guillén RamírezNo ratings yet

- Religion in Huck Finn NO Analytical ArgDocument5 pagesReligion in Huck Finn NO Analytical ArgRichard WangNo ratings yet

- Class 8 Holiday Homework - NewDocument14 pagesClass 8 Holiday Homework - Newchotu bhanuNo ratings yet

- Vstep 3.1Document6 pagesVstep 3.1Thư PhạmNo ratings yet

- Huckleberry Finn EssaysDocument7 pagesHuckleberry Finn Essayskbmbwubaf100% (2)

- Tom Sawyer Chapter 16 0Document4 pagesTom Sawyer Chapter 16 0Anonymous BZwNjBvs5ENo ratings yet

- Realism and Naturalism in Nineteenth C AmericaDocument249 pagesRealism and Naturalism in Nineteenth C America1pinkpanther99No ratings yet

- Character Analysis of Grandmother and Anders in Two Short StoriesDocument9 pagesCharacter Analysis of Grandmother and Anders in Two Short StoriesFlor Sfie100% (1)

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn NTDocument496 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry Finn NTvaliplaticaNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Chapters 8-15Document2 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Chapters 8-15ИванNo ratings yet

- NTA NET Solved English Question PaperDocument14 pagesNTA NET Solved English Question PaperVaibhavPathakNo ratings yet

- Character Analysis EssayDocument3 pagesCharacter Analysis Essayapi-2507151200% (1)

- Page 1Document164 pagesPage 1Ignacio Bermúdez RothschildNo ratings yet

- The Canterville Ghost: Book CardDocument2 pagesThe Canterville Ghost: Book CardDiana Roppo ValenteNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ DUYÊN HẢI- READING & WRITINGDocument10 pagesĐỀ DUYÊN HẢI- READING & WRITINGThu HườngNo ratings yet

- Lesson-Plan-reading Huck Finn Aug 15Document3 pagesLesson-Plan-reading Huck Finn Aug 15betti deleviNo ratings yet

- Mark Twain and American Realism PaperDocument7 pagesMark Twain and American Realism Paperapi-235622086No ratings yet

- Huck Finn & Rabbit Proof Fence Journey EssayDocument2 pagesHuck Finn & Rabbit Proof Fence Journey Essaythelittlegee100% (1)

- Hlam Notes 05Document27 pagesHlam Notes 05Paweł Stachura100% (1)

- Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain SummaryDocument2 pagesHuckleberry Finn by Mark Twain Summarymarizmoral100% (1)