Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Beautiful Words About Women

Uploaded by

TheVine0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

78 views6 pagesAlice von Hildebrand: Soren Kierkegaard seemed to derive an impish pleasure from putting us off track. She says no other thinker has written a series of works under various pseudonyms. In a book published posthumously, he informs us that his intention from the beginning was religious. Van Hildebrand says his views on women are ambiguous.

Original Description:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAlice von Hildebrand: Soren Kierkegaard seemed to derive an impish pleasure from putting us off track. She says no other thinker has written a series of works under various pseudonyms. In a book published posthumously, he informs us that his intention from the beginning was religious. Van Hildebrand says his views on women are ambiguous.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

78 views6 pagesBeautiful Words About Women

Uploaded by

TheVineAlice von Hildebrand: Soren Kierkegaard seemed to derive an impish pleasure from putting us off track. She says no other thinker has written a series of works under various pseudonyms. In a book published posthumously, he informs us that his intention from the beginning was religious. Van Hildebrand says his views on women are ambiguous.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Beautiful Words About Women

by Alice von Hildebrand

To write on Kierkegaard's thought is an act of daring. In a way this is true of many philosophers.

One only need think of the various interpretations given to Aristotle.

Those acquainted with the voluminous literature written about the greatest Danish philosopher (and

Kierkegaard remarked wittingly that "there is only one") will face a similar difficulty. Who was he?

One thing is certain: Soren Kierkegaard seemed to derive an impish pleasure from putting us off

track. To my knowledge, no other thinker has written a series of works under various pseudonyms.

When he published Either/Or (a work which unlike most of his publications enjoyed great success),

it was rightly suspected that the witty young man might be the author. He denied it in very strong

terms, but later acknowledged his authorship. He made this confession at a time when he

simultaneously claimed that none of his early works contain a single word which is his! Yet, Walter

Lowrie, a devoted admirer of Kierkegaard, argues that several of them contain valuable

biographical information.

In a remarkable book published posthumously, The Point of View for My Work as an Author,

Kierkegaard informs us that his intention from the very beginning of his career as a writer was

religious — something which is surprising indeed if one reads such works of his as Either/Or. He

intimates that, given the secularized nature of Denmark, the indirect way of communication was the

one which had a chance of catching the attention of "this individual who is my reader" and bringing

him to Christianity (later, however, he changed his mind). Kierkegaard was definitely a committed

Christian.

It is not my purpose here to discuss some of the contradictory interpretations of his thought that

scholars have offered; such would call for a whole book. In the framework of this article, my

modest concern is to shed some light on Kierkegaard's views on women. His position is ambiguous;

he has written about them both beautifully and spitefully. Deal Hudson, in his book An American

Conversion, tells us that he did not like Kierkegaard because the latter "did not like women" — a

remark likely to attract the sympathies of the fair sex.

I am going to take to Kierkegaard's defense and show that the few regrettable things he wrote about

women are largely compensated by the beautiful things he wrote about them, and that his insights

into the female personality and role in human and religious life could only come from the pen of

someone who has loved.

That Kierkegaard loved Regina Olsen is something no one can deny, for he says so explicitly and

unambiguously. It is true that a German "scholar" by the name of Schrempf contested this fact. But

Kierkegaard was in a privileged position to know his feelings for his fiancée; I find it wiser to trust

him.

The Soren Kierkegaard-Regina Olsen love story is certainly one of the most tragic in the history of

great love affairs. He fell in love with her; he conquered her; he got engaged to her and was hoping

to marry her. Then, to his horror and despair, he realized that he could not achieve the universal,

tread the common path, and marry the girl he loved. Kierkegaard was a penitent; he had received a

special calling which was not compatible with marriage. He often refers to the tragedy of Abraham,

who was called upon to sacrifice the son he loved. To read about how he broke off his engagement,

about her despair, about the humiliation to which her proud father submitted himself by begging

him not to abandon his daughter, and the qualms of conscience that Kierkegaard suffered make at

times painful reading. To the end of his life, he makes reference to this drama. At times, he hoped he

could, after all, make her his wife. All these hopes were dashed when he found out that she was

engaged to a previous beau that his ardent courtship had eliminated from the picture. That this was a

serious blow, that he probably had to fight against a certain bitterness and disappointment, is not

unlikely. He left her his literary bequest — this was rejected by Regina's husband, and it fell into the

hands of Kierkegaard's older brother, Peter. But this is not my concern here.

My claim is that someone who has written so beautifully about the love between man and woman,

who has tasted its sweetness and enchantment, cannot be a misogynist. Someone who has never

been deeply moved by the sublime beauty of a sunset would be well advised not to give a course on

aesthetics.

What does Kierkegaard have to say on the topic of women? We shall examine his observations in

The Woman Who Was a Sinner, an "Edifying Discourse" he composed shortly before his death, and

in Either/ Or, a book in which the young Kierkegaard etches two radically different conceptions of

life: Either is sheer hedonism; Or is an ethical conception of life and marriage. We shall purposely

omit the unflattering remarks that he puts in the mouth of characters etched in The Banquet, and

those clearly influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer, the misogynist par excellence. My exclusive aim

is to show that the sublime things he has written about women prove that the true Kierkegaard —

the fiancé of Regina — had deep insights into the mystery of femininity and the crucial role that

women play in both human and religious life.

He refers to "that unspeakable blissful feeling, the eternal force in the world earthly love" (Or). He

puts the following words in the mouth of Judge William, the defender of love and marriage in Or:

"For what would all my love and all my effort avail if she did not come to my aid, and what would I

avail if she did not arouse in me the enthusiasm to will?" How profoundly has Kierkegaard

understood that feelings — powerful as they may be — have little chance of survival if they are not

backed up by the will, which gives them their full reality and validity (ibid.). Dietrich von

Hildebrand, in his Ethics, calls this "sanctioning" valid feelings, just as one is called upon to

disavow "illegitimate feelings." How far Kierkegaard is from cheap romanticism and the dangerous

wallowing in one's own emotions sought for their own enjoyment and in which the object

motivating them is purely instrumental to achieve this self-seeking purpose.

Kierkegaard addresses himself to the perennial topic, the weakness of the female sex, so strikingly

formulated by Shakespeare: "Frailty, woman is thy name." Kierkegaard comments: "Woman is

weak — no, she is humble, she is much closer to God than man is. Hence it is that love is

everything to her, and she will certainly not disdain the blessing and confirmation which God is

ready to bestow upon her . . . Man is proud, he would be everything, would have nothing above

him" (Or). These are certainly not the words of a misogynist!

Kierkegaard understands the crucial role that God intends love to play in a woman's life. The

degradation nurtured by the feminist movement is to convince women that their greatness resides

not in love — a self-giving abandonment — but in rivaling males in creativity and exterior

accomplishments. It is a repeat of the sin of Esau, who sold his birthright for a mess of pottage. A

woman's mission is essentially a religious one. The noble role of women is religious, "for to a

woman it belongs essentially to pray for others" (ibid.).

That it is easier (or rather less difficult) for a woman to be humble finds its expression in the

following words: "A first love is humble and therefore rejoices that there is a power higher than it.

If only for the reason that it has someone to thank. (It is for this cause one finds a pure first love

more rarely in men than in women)" (ibid.).

Kierkegaard has also intuited that love is the crucial factor in a woman's life. It is the value that

unifies her, that makes sense of her existence. It is easy for her to grasp the meaning of the famous

sentence in The Canticle of Canticles that he who gives up everything for love would consider this

donation as nothing. He writes: "It would be very difficult to convince a woman that earthly love in

general might be sin, since by this affirmation her whole existence is destroyed in its deepest root"

(Or).

That many women betray this calling is, of course, true, just as it is also true that many men lose

sight of their noble mission to help and protect the weak. But a philosopher's approach is not

sociological. He is not — or should not be — concerned with statistics, but with "essences" — the

metaphysical "secret" of a being, unveiling what it is called upon to be. How profoundly has

Kierkegaard grasped the admirable complementarity which God has established between man and

woman: "It ennobles the whole man by the blush of bashfulness which belongs to woman but is the

corrector of man; for woman is the conscience of man . . . His proud wrath is quelled by the fact

that he turns back constantly to her. Her weakness is made strong by the fact that she leans upon

him" (ibid.).

Wrath is weakness under the appearance of strength; to acknowledge one's weakness and call for

help is true strength. This is why St. Paul writes, "It is when I am weak that I am strong" (2 Cor.

12:10). Man needs woman; woman needs man. (This is an admirable teaching of Catholic theology,

illuminating the role that Mary — the woman par excellence — played in redemption.)

Kierkegaard remarks that, according to Genesis, it is the man who leaves his father and mother, not

the woman. This certainly indicated that the Bible does not look down upon the woman: "A man

shall leave his father and his mother and shall cleave unto his wife" (2:24). We would expect it

rather to say that woman shall leave her father and mother and shall cleave unto her husband, for

woman is in fact the weaker sex. In the scriptural expression there is a recognition of woman's

importance, and "no knight could be more gallant toward her" (Or).

Kierkegaard rejects the view that marriage is exclusively the necessary means to procreate. But one

should not draw the conclusion that he would favor artificial birth control or abortion. He sees the

child as a fruit of love, and not as the exclusive purpose of marriage, which, if it were so, would

render love an unnecessary addition: "And yet such a marriage [exclusively for the sake of

procreation] is as unnatural as it is arbitrary, nor has it any support in Holy Scripture. For in the

Bible we read that God established marriage because 'it is not good for man to be alone,' hence in

order to give him company" (ibid.). And: "it is always an insult to a girl to want to marry her for any

other reason than because one loves her" (ibid.).

That Kierkegaard understands the dignity of a child is expressed in the following words: "the

highest thing one person can owe another is . . . life" (ibid.). And: "Children belong to the inmost

and most hidden life of the family . . . every child has a halo around its head . . . the father will feel

with humility that the child is a trust, and that he is in the most beautiful sense of the word only a

stepfather" (ibid.).

Kierkegaard has a keen sense of the mystery of love. How far it is from a cold, rational calculation

in which one makes a careful list of the desirable qualities that a spouse should possess.

An objection that could be raised to what Sheldon Vanauken calls "the wrinkled of heart" (A Severe

Mercy) is that the Church does not ask the Bride and the Bridegroom whether they love each other,

but whether they are willing to bind themselves with the bonds of marriage. Kierkegaard has a

prompt answer: "If the Church does not ask if they love one another, this is by no means because it

would nullify earthly love, but because it assumes it" (Or). He adds: "all the talk about the

disparagement of love by the Church is utterly unfounded and exists only for him who has taken

offense at religion" (ibid.).

These quotations should be read in connection with Kierkegaard's claim that, for women, love is

everything. He sheds light on the role she is to play in marriage — a communion that should always

be lit by the light and warmth of love, for marriage is the pillar of society.

Not only is the woman the heart, but because the affective sphere is her anchor, she is given a great

talent to read into the soul of her mate. Kierkegaard writes: "who is such a judge of men as is a

woman?" (ibid.).

The importance of women is often downgraded or even denigrated because she is called upon to

deal with the small and indispensable tasks of human life — the tasks that the French poet Verlaine

calls "les travaux ennuyeux et faciles" (the boring and simple tasks). But Kierkegaard's sharp glance

makes him understand that a special loving talent is required to elevate small things through the

loving attention given them. A little French girl (St. Therese of Lisieux) who became a saint and

died some 40 years after him would unveil a secret of sainthood: Do everything with love, even

small tasks such as cleaning or cooking. Kierkegaard writes: "She [woman] was created to deal with

the small, and knows how to give it an importance, a dignity, a beauty which enchants. Marriage

liberates one from habits, from the tyranny of one-sidedness, from the yoke of whims" (ibid.).

One of Kierkegaard's deep insights is his understanding that "habit" is a deadly enemy. To say one's

prayers by rote while thinking about something else; to kiss one's spouse out of habit, or to go to

church because one has always done it is to inject a poison into meaningful things. This is why he

writes in Works of Love that "one hundred cannons should warn us against the danger of habit."

Habit puts dust on everything it touches. It kills poetry; it freezes the buds of spring.

Kierkegaard has also grasped the paradoxical character of women, a paradox which some men find

so difficult to understand, that a man is best equipped to understand a woman — and vice versa. But

this presupposes a deep mutual love. St. Claire of Assisi was no doubt the best disciple of St.

Francis of Assisi; St. Jeanne Françoise de Chantal had a unique understanding of the holiness of St.

Francis de Sales. This is a pattern that keeps repeating itself.

The mysterious side of women is expressed by Kierkegaard in the following words: "It belongs to

her nature to be more perfect and more imperfect than man. If one would indicate the purest and

most perfect quality, one says 'a woman'; if one would indicate the weakest, and most feeble thing,

one says 'a woman'; if one would give a notion of a spiritual quality raised above all sensuousness,

one says 'a woman'; if one would give a notion of the sensuous, one says 'a woman'; if one would

indicate innocence in all its lofty greatness, one says 'a woman'; if one would point to the depressing

feeling of sin, one says 'a woman.' In a certain sense, therefore, woman is more perfect than man,

and this the scripture expresses by saying that she has more guilt" (Or).

Kierkegaard confessed on his death bed that his life had been a long suffering. He knew its bitter

taste and he also knew its purifying effect if properly accepted and embraced. No doubt, this gave

him a deep insight into the fate of women to give birth in pain and anguish; he knew that it is

probably easier for a woman to understand that there is a deep bond between suffering and love,

suffering out of love: "Is she not as close to God as you? Will you deprive her of the opportunity of

finding God in the deepest and most heartfelt way — through pain and suffering?" (ibid.).

It also was his conviction that women have a religious mission toward men. Whereas Eve was a

temptress who led her husband to a fall, she finds in Christianity her true role — to help him toward

God: "above all have a little more reverence for women," Kierkegaard wrote, "believe me, from her

comes salvation, as surely as hardening comes from man. It is my conviction that if it was a woman

that ruined man, it was woman also that has fairly and honestly made reparation and still does so;

out of a hundred men who go astray in the world, ninety and nine are saved by women and one by

immediate divine grace . . . You can easily see that in my opinion woman [when she restores a man

to this state] makes due requital for the harm she has done" (ibid.).

Kierkegaard is a radical enemy of feminism. He views it as a diabolical plan to ruin both femininity

and the salvific role women are called upon to play. He writes: "I hate all talk about the

emancipation of woman. God forbid that ever it may come to pass. I cannot tell you with what pain

this thought is able to pierce my heart, nor what passionate exasperation, what hate I feel toward

everyone who gives vent to such talk" (ibid.).

Prophetically, Kierkegaard foresees the horror of a unisex society: 'But the poor wretches know not

what they do, they are not able to be men, and instead of learning to be that, they would ruin woman

and would be united with her on terms of remaining what they were, half-men . . ." (ibid.).

One could object that I am contradicting myself: I have mentioned above that Kierkegaard claimed

that his early works do not reflect his own views. But the same thing can be said of The Banquet,

which contained some very unflattering remarks about the weaker sex.

This is why I shall conclude by referring to an "Edifying Discourse" to his Training in Christianity

that Kierkegaard wrote shortly before his death and which I consider to be his "last will" on the

question of femininity. It is titled The Woman Who Was a Sinner. No one reading it could possibly

draw the conclusion that Kierkegaard was a misogynist.

The Woman Who Was a Sinner contains a sublime eulogy about a woman — the match of which is

not easy to find. It should be read by everyone who has a sincere interest in Kierkegaard's thought.

No commentary upon this text can be satisfactory, for what Kierkegaard writes is so admirably

formulated that grateful receptivity alone is called for. The "ungodly rage" of feminists might have

been somewhat quelled had they been acquainted with the insights of a thinker who through prayer

and suffering had understood the noble mission of those who are told to "keep silent in the

churches" (1 Cor.14:34). The calling of women is to piety and godliness. This is precisely what it

means to remain silent — for to keep silent in front of God is to drink at this holy fount of wisdom

which teaches one godliness.

The danger of many men be they professors Kierkegaard hated so much, be they contemporary

theologians who want to explain everything and irreverently tear the veil concealing holy mysteries

— is that they raise questions about things that God, in His infinite wisdom, has chosen not to

reveal. Instead of reverently dwelling on the rich fullness of revealed truths, they want to conquer

by reason "the secrets of the kingdom" (Mt. 13:11). The result being that because of their proud lack

of receptivity toward the con-tent of divine revelation, they arrogantly want to teach God — and

become very foolish in their worldly wisdom (1 Cor. 1).

How very different from Mary's attitude. And because of her faith and silence, her holy receptivity,

she was granted to become the mother of the Savior. Kierkegaard had already mentioned in Or that

"woman believes that with God all things are possible." Now, his theme is to praise Mary, the

blessed one among women who "kept all these things in her heart" though not understanding. No

doubt, for him, Mary was the model of femininity, and Mary Magdalene, the sinner, who was also

at the foot of the cross, learned from her that "one thing alone is necessary" (Lk. 10:42).

Feminism manifests its evil genius by offering a caricature of femininity and misreading the order

of St. Paul that women should "keep silent in the churches." To feminists it seals their inferiority. In

fact, the very opposite is true: To remain silent is to accept being fecundated, and to be fecundated

by God is to be blessed. It is written in the Gospel that men will be held responsible for every

unnecessary word they have uttered. One shudders at the thought of the endless perorations of some

pompous theologians who inundate libraries with "theories" that are at odds with God's revelation,

which, as Kierkegaard writes, should be read on one's knees — as one reads a letter from one's

fiancée.

Just as one thing alone is necessary, Mary Magdalene teaches us that there is one source of great

sorrow: grief over one's sinfulness. Real contrition is a response of profound grief because one has

offended the Holy One whom one now loves with every fiber of one's being. Mary Magdalene has

— through God's grace — ascended very high on the scale of perfection, but the higher she finds

herself, the more she will recall that she is "the woman who was a sinner." The more miserable she

sees herself to be, the more she loves the One who has come not for the righteous but to save

sinners. Mary Magdalene will not be forgotten because she did not forget — and did not want to

forget — that she was a sinner who has been forgiven.

Kierkegaard grants us that man is stronger than "weak woman." But this very weakness is

compensated — as he emphatically underlines — by the fact that she is "unified." Man has many

thoughts; Mary Magdalene has but one. She has one sorrow, that she is a sinner. She has only one

burning desire: to be forgiven. This burning desire to be forgiven is expressed by her tears, and the

gift of a precious perfume poured on the Holy One. The fact that she dries His feet with her hair,

expresses her religious "seriousness," for, Kierkegaard tells us, this is precisely what seriousness

means. Mary Magdalene's sorrow over her sinful life does not drive her to despair — the "sickness

unto death" — but to loving confidence that He who is love and mercy will cleanse her of her sins.

Responding to the "offense" taken by the disciples that the money spent on this precious ointment

should have been given to the poor, Christ says that there will always be poor among us, and that

wherever His Gospel will be preached, her deed of contrition and love will be proclaimed. This

precious perfume symbolizes an act of adoration — the only adequate response to God. Mary

Magdalene teaches us that this response to His holiness is the liturgical act par excellence. This is

what the Holy Liturgy teaches us. This is what is being forgotten today.

Mary Magdalene's loving repentance makes her scorn shame, disgrace, and humiliation: She is

publicly acknowledged to be a sinner. But all this she tramples under foot because she loves Him

who is love, and knows that there is greater joy in Heaven for a repentant sinner than for one

hundred "just" who have no need of repentance.

Kierkegaard tells us that Mary Magdalene (a model for all women) experiences "infinite

indifference" — an indifference which is at the antinodes of the cynical, diabolical "nothing

matters" attitude which has gained currency in some modern literature. What does it matter what

people think of her or say about her? She has conquered this holy indifference because she knows

that men tend to be chatterboxes who make noise but say nothing. She loves, and trusts that much

will be forgiven her because she has loved much.

To conclude, let me refer to Pastor Boesen's testimony about Kierkegaard, he who was

Kierkegaard's closest friend. Boesen tells us that Kierkegaard was the purest man he had ever

known, that he "stood in a finer, purer and higher relationship to women" than other men. It is

impossible to be pure and not to respect women.

In light of this, it should be evident that to compare Kierkegaard to Nietzsche — who, brutally,

advises men never to forget their whip when they go to a woman — is not only unfortunate but very

unjust.

Man-haters and woman-haters are to be pitied indeed because they are blind to the biblical teaching

that they are made for each other and are called to help each other to love the One who is the source

of all love.

Alice von Hildebrand is Professor Emerita of Philosophy at Hunter College of the City University

of New York. She is the author, most recently, of The Soul of a Lion (Ignatius), about her late

husband, the Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand; The Privilege of Being a Woman

(Sapientia Press); and By Love Refined (Sophia Institute Press). She has written extensively for

many Catholic periodicals and appears frequently on Mother Angelica's EWTN.

You might also like

- Kierkegaard's Writings, VI, Volume 6: Fear and Trembling/RepetitionFrom EverandKierkegaard's Writings, VI, Volume 6: Fear and Trembling/RepetitionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (131)

- Philosopher of the Heart: The Restless Life of Søren KierkegaardFrom EverandPhilosopher of the Heart: The Restless Life of Søren KierkegaardRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Weavers: a tale of England and Egypt of fifty years ago - CompleteFrom EverandThe Weavers: a tale of England and Egypt of fifty years ago - CompleteNo ratings yet

- The Mayor of Casterbridge (with an Introduction by Joyce Kilmer)From EverandThe Mayor of Casterbridge (with an Introduction by Joyce Kilmer)No ratings yet

- Fear and Trembling and The Sickness Unto DeathFrom EverandFear and Trembling and The Sickness Unto DeathRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (66)

- Kierkegaard's Writings, X, Volume 10: Three Discourses on Imagined OccasionsFrom EverandKierkegaard's Writings, X, Volume 10: Three Discourses on Imagined OccasionsNo ratings yet

- Provocations: Spiritual Writings of KierkegaardFrom EverandProvocations: Spiritual Writings of KierkegaardRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- A Literary Shema: Annie Dillard’s Judeo-Christian Vision and VoiceFrom EverandA Literary Shema: Annie Dillard’s Judeo-Christian Vision and VoiceNo ratings yet

- Kierkegaard's Existentialism: The Theological Self and The Existential SelfFrom EverandKierkegaard's Existentialism: The Theological Self and The Existential SelfNo ratings yet

- The Soul of Kierkegaard: Selections from His JournalsFrom EverandThe Soul of Kierkegaard: Selections from His JournalsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Microcosmography or, a Piece of the World Discovered; in Essays and CharactersFrom EverandMicrocosmography or, a Piece of the World Discovered; in Essays and CharactersNo ratings yet

- The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 04, No. 22, August, 1859 A Magazine of Literature, Art, and PoliticsFrom EverandThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 04, No. 22, August, 1859 A Magazine of Literature, Art, and PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Fear and Trembling Paper For Kierkegaard SubjectDocument6 pagesFear and Trembling Paper For Kierkegaard SubjectDeo de los ReyesNo ratings yet

- How to Misunderstand Kierkegaard: An Instruction Manual for Assistant Professors and Other Immoral and Disreputable PersonsFrom EverandHow to Misunderstand Kierkegaard: An Instruction Manual for Assistant Professors and Other Immoral and Disreputable PersonsNo ratings yet

- Hildegard of Bingen: Commentary On The Johannine PrologueDocument18 pagesHildegard of Bingen: Commentary On The Johannine ProloguePedro100% (1)

- From Despair to Faith: The Spirituality of Søren KierkegaardFrom EverandFrom Despair to Faith: The Spirituality of Søren KierkegaardNo ratings yet

- Kierkegaard's Writings, XXI, Volume 21: For Self-Examination / Judge For Yourself!From EverandKierkegaard's Writings, XXI, Volume 21: For Self-Examination / Judge For Yourself!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Voodoo Tales: The Ghost Stories of Henry S WhiteheadFrom EverandVoodoo Tales: The Ghost Stories of Henry S WhiteheadRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- The Substance of Shakespearean TragedyDocument2 pagesThe Substance of Shakespearean TragedySruti Md100% (1)

- Kierkegaard's Writings, XXIII, Volume 23: The Moment and Late WritingsFrom EverandKierkegaard's Writings, XXIII, Volume 23: The Moment and Late WritingsNo ratings yet

- Søren KierkegaardDocument20 pagesSøren Kierkegaardjaga64No ratings yet

- Bøggild. Reflections of Kierkegaard in The Tales of AndersenDocument15 pagesBøggild. Reflections of Kierkegaard in The Tales of AndersenjuanevaristoNo ratings yet

- Oscar Wilde, His Life and Confessions by Frank Harris (Illustrated)From EverandOscar Wilde, His Life and Confessions by Frank Harris (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- The Poetical Works of John Dryden, Volume 2 With Life, Critical Dissertation, and Explanatory NotesFrom EverandThe Poetical Works of John Dryden, Volume 2 With Life, Critical Dissertation, and Explanatory NotesNo ratings yet

- J.D. Ponce on Søren Kierkegaard: An Academic Analysis of Either/Or: Existentialism Series, #1From EverandJ.D. Ponce on Søren Kierkegaard: An Academic Analysis of Either/Or: Existentialism Series, #1No ratings yet

- Sartor Resartus, and On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in HistoryFrom EverandSartor Resartus, and On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in HistoryNo ratings yet

- Uncivil Unions: The Metaphysics of Marriage in German Idealism and RomanticismFrom EverandUncivil Unions: The Metaphysics of Marriage in German Idealism and RomanticismNo ratings yet

- The Soul as Virgin Wife: Mechthild of Magdeburg, Marguerite Porete, and Meister EckhartFrom EverandThe Soul as Virgin Wife: Mechthild of Magdeburg, Marguerite Porete, and Meister EckhartNo ratings yet

- Faith Rising—Between the Lines: Intimations of Faith Embedded in Modern FictionFrom EverandFaith Rising—Between the Lines: Intimations of Faith Embedded in Modern FictionNo ratings yet

- Thrillofthechaste:The Pursuitof Love'Asthe Perpetualdialectic Betweenthe Real'Andthe Idealimage'In Kierkegaard'Sthe Seducer'SdiaryDocument18 pagesThrillofthechaste:The Pursuitof Love'Asthe Perpetualdialectic Betweenthe Real'Andthe Idealimage'In Kierkegaard'Sthe Seducer'SdiarysemluzNo ratings yet

- Analysis On The Seducer's DiaryDocument19 pagesAnalysis On The Seducer's DiaryBrigette MolanoNo ratings yet

- KierkegaardDocument14 pagesKierkegaardNiloIbarraNo ratings yet

- KierkegaardDocument10 pagesKierkegaardThomas Scott JonesNo ratings yet

- Translation of Levinas's Review of Lev Shestov's Kierkegaard and The Existential PhilosophyDocument8 pagesTranslation of Levinas's Review of Lev Shestov's Kierkegaard and The Existential PhilosophymoonwhiteNo ratings yet

- Harold Bloom Franz KafkaDocument244 pagesHarold Bloom Franz KafkaEma Šoštarić100% (9)

- Comparison of 3 Tests To Detect Acaricide ResistanDocument4 pagesComparison of 3 Tests To Detect Acaricide ResistanMarvelous SungiraiNo ratings yet

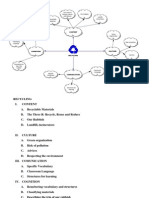

- Recycling Mind MapDocument2 pagesRecycling Mind Mapmsole124100% (1)

- ANS: (2.59807m/s2 Horizontal) (1.5m/s2 Vertical) (12.93725 Degree Angle That The Water Surface Makes With The Horizontal)Document5 pagesANS: (2.59807m/s2 Horizontal) (1.5m/s2 Vertical) (12.93725 Degree Angle That The Water Surface Makes With The Horizontal)Lolly UmaliNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case StudyDocument20 pagesClinical Case Studyapi-252004748No ratings yet

- By This Axe I Rule!Document15 pagesBy This Axe I Rule!storm0% (1)

- SCIENCEEEEEDocument3 pagesSCIENCEEEEEChristmae MaganteNo ratings yet

- Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces 3. Regular SurfacesDocument16 pagesDifferential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces 3. Regular SurfacesyrodroNo ratings yet

- SR6 Core Rulebook Errata Feb 2020Document6 pagesSR6 Core Rulebook Errata Feb 2020yrtalienNo ratings yet

- Modified Phosphate and Silica Waste in Pigment PaintDocument12 pagesModified Phosphate and Silica Waste in Pigment PaintDani M RamdhaniNo ratings yet

- Antoine Constants PDFDocument3 pagesAntoine Constants PDFsofiaNo ratings yet

- Aircraft Design Course PhillStocking 4.2Document48 pagesAircraft Design Course PhillStocking 4.2ugurugur1982No ratings yet

- Rido, Rudini - Paediatric ECGDocument51 pagesRido, Rudini - Paediatric ECGFikriYTNo ratings yet

- Furuno CA 400Document345 pagesFuruno CA 400Димон100% (3)

- Texto CuritibaDocument1 pageTexto CuritibaMargarida GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- MioPocket ReadmeDocument30 pagesMioPocket Readmelion78No ratings yet

- Microbiology Part 3Document74 pagesMicrobiology Part 3Authentic IdiotNo ratings yet

- St. John's Wort: Clinical OverviewDocument14 pagesSt. John's Wort: Clinical OverviewTrismegisteNo ratings yet

- Orofacial Complex: Form and FunctionDocument34 pagesOrofacial Complex: Form and FunctionAyushi Goel100% (1)

- YogaDocument116 pagesYogawefWE100% (2)

- 04 SAMSS 005 Check ValvesDocument9 pages04 SAMSS 005 Check ValvesShino UlahannanNo ratings yet

- ASCE Snow Loads On Solar-Paneled RoofsDocument61 pagesASCE Snow Loads On Solar-Paneled RoofsBen100% (1)

- BTK Implant Guide SurgeryDocument48 pagesBTK Implant Guide SurgeryMaria VolvinaNo ratings yet

- Updated SAP Cards Requirement JalchdDocument51 pagesUpdated SAP Cards Requirement Jalchdapi-3804296No ratings yet

- 7 +Royal+Court+Affairs,+Sultanate+of+OmanDocument12 pages7 +Royal+Court+Affairs,+Sultanate+of+OmanElencheliyan PandeeyanNo ratings yet

- TranscriptDocument1 pageTranscriptapi-310448954No ratings yet

- Nutrient DeficiencyDocument8 pagesNutrient Deficiencyfeiserl100% (1)

- Angewandte: ChemieDocument13 pagesAngewandte: ChemiemilicaNo ratings yet

- Unnatural Selection BiologyDocument2 pagesUnnatural Selection BiologyAlexa ChaviraNo ratings yet

- Efficient Rice Based Cropping SystemDocument24 pagesEfficient Rice Based Cropping Systemsenthilnathan100% (1)

- The Unofficial Aterlife GuideDocument33 pagesThe Unofficial Aterlife GuideIsrael Teixeira de AndradeNo ratings yet