Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Minute Order 1

Uploaded by

Caleb NewquistCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Minute Order 1

Uploaded by

Caleb NewquistCopyright:

Available Formats

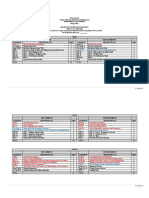

Order Form (01/2005)

Case: 1:07-cv-04507 Document #: 294 Filed: 06/29/10 Page 1 of 6 PageID #:8706

United States District Court, Northern District of Illinois

Name of Assigned Judge or Magistrate Judge

Amy J. St. Eve 07 C 4507

Sitting Judge if Other than Assigned Judge

CASE NUMBER CASE TITLE

DOCKET ENTRY TEXT

DATE Silverman vs. Motorola, Inc et al.

6/29/2010

KPMG LLP's Motion to Quash or Modify Subpoena and for Protective Order [237] is denied.

O[ For further details see text below.]

Notices mailed by Judicial staff.

STATEMENT Before the Court is non-parties KPMG LLP, David Pratt, and Dennis Parrotts (collectively KPMG) Motion to Quash or Modify Subpoena and for Protective Order. For the following reasons, the Court denies KPMGs motion. BACKGROUND This class action concerns Defendants alleged violations of 10(b) and 20(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and Rule 10b-5 promulgated thereunder. Plaintiffs allege that Motorola and certain executive officers made public misstatements and material omissions regarding Motorolas 3G mobile handset portfolio. Plaintiffs contend that throughout the Class Period (July 2006-January 2007), Motorolas 3G portfolio was not on track or running on the Argon platform due, in part, to third party supplier Freescale Semiconductor, Inc.s (Freescale) failure to provide chipsets to Defendants on time. Plaintiffs further allege that rather than disclosing the potential delays in the 3G product launch, Motorola continued to assert that its products would ship in late 2006. Motorola, however, did not launch a Motorola 3G phone until 2007. Continued...

Courtroom Deputy Initials:

KF

07C4507 Silverman vs. Motorola, Inc et al.

Page 1 of 6

Case: 1:07-cv-04507 Document #: 294 Filed: 06/29/10 Page 2 of 6 PageID #:8707 During the discovery period, Plaintiffs filed a motion to compel Defendants to produce documents related to licensing agreements that Defendants entered into with Freescale and Qualcomm, Inc. (Qualcomm) at the end of the third quarter of 2006 (3Q06). The Court granted Plaintiffs motion to compel in part noting that, [t]he fact that Defendants entered into licensing agreements with Freescale and Qualcomm in late 3Q06, especially considering Freescales role in the delay of the 3G releases, and that Defendants included the earnings from those agreements in their 3Q06 earnings statements could evidence an attempt to cover up the failed 3G developments. (R. 200, pp. 3-4.) Plaintiffs Second Amended Complaint, filed on March 15, 2010, contains allegations that Defendants failed to disclose the nature and financial effect of either the Freescale and Qualcomm 3Q06 IP transactions, which far exceeded $50.00 million, in blatant violation of GAAP and SEC rules. (R. 211-1, Second Amended Complaint, 153.) Defendants have raised as an affirmative defense that, Motorola accounted for and/or disclosed all material transactions consistent with generally accepted accounting principles and the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission. (R. 220, Fifty-Seventh Affirmative Defense, p. 126.) Plaintiffs have now issued two subpoenas to KPMG, the registered accounting firm that conducted audits and reviews of Motorolas financial statements during and for the year ending December 31, 2006. (R. 238-1, KPMGs Mot. to Quash, p. 1.) Among other things, the subpoenas seek [a]ll documents and communications concerning the Public Company Accounting Oversight Boards [(PCAOB)] review of KPMGs 3Q06 quarterly review and 2006 audit of [Motorolas] Mobile Devices segment, including, but not limited to the sufficiency of KPMGs audit procedures and audit documentation of the 3Q06 IP Licensing Transactions. Id. at Exs. H and I. Plaintiffs also seek to take the depositions of Mr. Parrott and Mr. Pratt. Id. at Exs. J and K. LEGAL STANDARD I. Motion to Quash

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provide that a court shall quash or modify a subpoena if it requires disclosure of privileged information or subjects a person to undue burden. Fed.R.Civ.P. 45(c)(3)(A). A district court may quash or modify a subpoena if it seeks discovery that is unreasonably cumulative or duplicative, or is obtainable from some other source that is more convenient, less burdensome, or less expensive; [or] the party seeking discovery has had ample opportunity by discovery in the action to obtain the information sought. Fed.R.Civ.P. 26(b)(2). Motions to quash are within the sound discretion of the district court. Wollenburg v. Comtech Mfg. Co., 201 F.3d 973, 977 (7th Cir. 2000) (citing U.S. v. Ashman, 979 F.2d 469, 495 (7th Cir. 1992)). II. Motion for Protective Order

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure also provide that a court may, for good cause, issue an order to protect a party or person from annoyance, embarrassment, oppression, or undue burden or expense. Fed.R.Civ.P. 26(c). A court may also specify the time or place of discovery, or limit the scope of discovery to certain matters. Fed.R.Civ.P. 26(c). The burden to show good cause is on the party seeking the protective order. Johnson v. Jung, 242 F.R.D. 481, 483 (N.D. Ill. 2007) (citing Jepson, Inc. v. Makita Elec. Works, Ltd., 30 F.3d 854, 858 (7th Cir. 1994)). Conclusory statements of hardship are not sufficient to carry this burden. Id. ANALYSIS In its motion, KPMG seeks to quash the subpoenas issued to it by Plaintiffs and to preclude Plaintiffs from questioning KPMG, through Mr. Pratt and Mr. Parrott, regarding the PCAOB inspection process. Resolution of KPMGs motion turns on the statutory language of a provision of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (the Act) which, in part, created the PCAOB. One circuit court has explained the creation of the PCAOB as follows:

07C4507 Silverman vs. Motorola, Inc et al.

Page 2 of 6

Case: 1:07-cv-04507 Document #: 294 Filed: 06/29/10 Page 3 of 6 PageID #:8708 Following the Enron and Worldcom accounting scandals that exposed serious weaknesses in industry self-regulatory reporting requirements for certain publicly held companies, Congress enacted the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, 15 U.S.C. 7201 et seq. n1. Title I of the Act established the Board to oversee the audit of public companies that are subject to the securities laws . . . in order to protect the interests of investors and further the public interest in the preparation of informative, accurate, and independent audit reports. 15 U.S.C. 7211(a). The five members of the Board are appointed by the Commission after consultation with the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and the Secretary of the Treasury. Id. 7211(e)(4)(A). The Act empowers the Board, subject to the oversight of the Commission, to, among other things, register public accounting firms, establish auditing and ethics standards, conduct inspections and investigations of registered firms, impose sanctions, and set its own budget, which is funded by annual fees. Id. 7211(c), 7219(c), (d). Free Enter. Fund v. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Bd., 537 F.3d 667, 669 (D.C. Cir. 2008).1 At issue here, Section 10(b)(5)(A) of the Act provides: (A) Confidentiality. Except as provided in subparagraph (B), all documents and information prepared or received by or specifically for the Board, and deliberations of the Board and its employees and agents, in connection with an inspection under section 104 [15 USCS 7214] or with an investigation under this section, shall be confidential and privileged as an evidentiary matter (and shall not be subject to civil discovery or other legal process) in any proceeding in any Federal or State court or administrative agency, and shall be exempt from disclosure, in the hands of an agency or establishment of the Federal Government, under the Freedom of Information Act (5 U.S.C. 552a), or otherwise, unless and until presented in connection with a public proceeding or released in accordance with subsection (c). 15 U.S.C. 7215(b)(5)(A). The privilege created by the Act has not been addressed by any courts and is a matter of first impression. Plaintiffs have agreed to exclude from their request documents that KPMG created specifically in response to a request from the PCAOB. (R. 238-1, p. 5.) KPMG objects, however, to production of documents concerning the PCAOB inspection process or any documents created . . . in connection with a PCAOB inspection. Id. at pp. 6, 11. KPMG argues that if litigants can compel production of materials related to the PCAOBs confidential inspection process notwithstanding section 105(b)(5)(A), open and constructive engagement between the PCAOB and accounting firms could be chilled by the threat of increased civil litigation, and the statutory framework carefully crafted by Congress to improve the quality of public company audits could be frustrated. Id. at p. 12. KPMGs arguments, however, miss the mark. While KPMG spends a significant portion of its opening brief pointing to the legislative history and purpose of the Act, KPMG fails to address the fact that the language creating the statutory privilege in Section 105(b)(5)(A) is exceedingly clear. Indeed, while KPMG attempts to narrow its privilege claim in its reply brief by asserting that, KPMGs position is, and always has been, that documents and information that are created in response to a PCAOB inspection and that relate or reflect the substance of the inspection process such as internal KPMG communications that discuss, but are not

The United States Supreme Court reversed the District of Columbia Circuits ruling on June 28, 2010 finding that the dual-for-cause limitations on the removal of PCAOB members contravene the Constitutions separation of powers. The Supreme Court, however, held that the unconstitutional provisions of the statute were severable from the remainder of the statute and that the remainder of the statute remains fully operative. Free Enter. Fund v. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Bd., --- S.Ct. ----, 2010 WL 2555191 (June 28, 2010). Neither the District of Columbia Circuit nor the Supreme Court addressed the provisions of the statute at issue here.

07C4507 Silverman vs. Motorola, Inc et al. Page 3 of 6

Case: 1:07-cv-04507 Document #: 294 Filed: 06/29/10 Page 4 of 6 PageID #:8709 in themselves, communications with the Board or the inspectors, or that discuss the content of confidential questions, comments, or critiques made by Board inspectors, or that reflect the firms development of responses to those questions, comments or critiques ultimately to be communicated to the Boards inspection team are protected. (R. 268, KPMGs Reply, p. 9.) Such an attenuated view of the privilege created by the statute is unsupported by its text. It is a cardinal principal of statutory construction that a court must give effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute. Duncan v. Walker, 533 U.S. 167, 174 (2001) (internal citations omitted). Legislative history comes into play only when necessary to decode an ambiguous enactment; it is not a sine qua non for enforcing a straightforward text. DirecTV, Inc. v. Barczewski, 604 F.3d 1004 (7th Cir. 2010). Here, Section 105(b)(5)(A) protects from disclosure only materials that an accounting firm prepared . . . specifically for the Board. There is no ambiguity in this statutory provision and the Court need not look any further than the text of the statue in order to resolve the pending motion. Inclusion of the phrase specifically for the Board makes clear that Section 105(b)(5)(A) is applicable to only a portion of any information or documents that may derive from, refer to, or relate to a PCAOB inspection. The reading of the statute proffered by KPMG, which includes any documents related to or concerning the PCAOB inspection process, extends interpretation of the provision beyond its plain language and renders meaningless the phrase specifically for the Board. In addition, the argument set forth in the Center for Audit Quality (CAQ)s amicus curiae brief that [i]nternal KPMG documents relating to the inspection process are prepared . . . specifically for the Board because, absent the inspection, they would never have been created in the first place is not persuasive. (R. 253-1, CAQs Brief, p. 10.) If Congress intended the privilege to protect all materials related to the inspection, the text of the statute would reflect that intention. Instead, the statute limits the protection to materials prepared specifically for the Board. Despite significant argument by KPMG and CAQ regarding the legislative history of the Act, because the plain language of the statute is clear, the Court need not look beyond its text. See, e.g, United States v. BDO Seidman, LLP, 492 F.3d 806, 824 (7th Cir. 2007) (noting that because the statutory tax shelter exception to the tax practitioner privilege is not ambiguous, the court need not look to legislative history to determine its meaning).2 KPMG also argues that documents relating to the PCAOBs inspection of KPMGs audit practice are irrelevant to this litigation. KPMG asserts that because violations of accounting and auditing standards are generally insufficient to support a claim for securities fraud, any documents it may produce would be irrelevant to the litigation. (R. 228-1, KPMGs Mot. to Quash, pp. 14-15.) KPMGs reliance, however, on a 25-year-old non-controlling case purportedly establishing the elements of a reliance on professional services defense is unavailing. (R. 268-1, KPMGs Reply, p. 11.) Moreover, Plaintiffs have alleged that Defendants entered into a series of transactions with Freescale and Qualcomm in late 3Q06 to inflate Motorolas 3Q06 results. In response, Defendants have raised as an affirmative defense that, Motorola accounted for and/or disclosed all material transactions consistent with generally accepted accounting principles and the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission. (R. 220, Fifty-Seventh Affirmative Defense, p. 126.) Because Defendants have placed their accounting at issue by contending that Motorola acted in conformance with generally accepted accounting principles, Defendants have necessarily placed KPMGs communications regarding Motorolas 3Q06 deals directly at issue. See, e.g., Robin v. Doctors Officenters Corp., 1986 WL 8054, 1986 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22836 (N.D. Ill. July 14, 1986) (granting plaintiffs motion to compel in a Rule 10b-5 case which sought all accounting

Plaintiffs also conclusorily assert that the statute provides the privilege lies in the hands of the PCAOB, not KPMG. (R. 261, Pls. Oppn, p. 9.) This argument, however, is not supported by the plain language of the statute. Indeed, Plaintiffs fail to explain or support their contention in this regard. The argument is accordingly waived. See Bryant v. Gardner, 587 F. Supp. 2d 951, 965 (N.D. Ill. 2008) (citing De La Rama v. Ill. Dept of Human Servs., 541 F.3d 681, 688 (7th Cir 2008) (Unsupported and undeveloped arguments are waived.).

07C4507 Silverman vs. Motorola, Inc et al. Page 4 of 6

Case: 1:07-cv-04507 Document #: 294 Filed: 06/29/10 Page 5 of 6 PageID #:8710 work papers, correspondence and memorandum from non-party firm that conducted an audit of defendant where the non-party firm had audited and certified the financial statements that were referenced in the allegedly false and misleading prospectus). Given that the PCAOB conducted an investigation of KPMG to determine whether its audits complied with professional standards and that the PCAOB made specific findings regarding deficiencies associated with KPMGs auditing procedures of the 3Q06 licensing transactions, these documents are directly relevant to this litigation. (R. 261-1, Ex. A, PCAOB Report on 2007 Inspection of KPMG LLP.) In addition, in its initial motion, KPMG briefly asserts that the subpoenas are unduly burdensome due to its status as a non-party and because Plaintiffs have other means to ascertain the information. In its reply brief, KPMG explains that it does not raise the burden argument as a stand-alone basis for granting the motion to quash, but instead contends that if Plaintiffs are permitted to invade the PCAOB inspection process, Congress cooperative inspection model will likely be negatively impacted. (R. 268-1, KPMGs Reply, p. 13.) The Court recognizes that non-parties are entitled to somewhat greater protection in the discovery process than parties to the litigation. Thayer v. Chiczewski, 257 F.R.D. 466, 469 (N.D. Ill. 2009). Indeed, [s]ubpoenaed non-parties have the right to challenge the burdensomeness and expense of responding to the subpoena, pursuant to [Rule] 45(c). Id. Whether a subpoena imposes an undue burden upon a witness is a case specific inquiry that turns on such factors as relevance, the need of the party for the documents, the breadth of the document request, the time period covered by it, the particularity with which the documents are described and the burden imposed. Id. In the present circumstances, Plaintiffs have shown that the documents they seek are relevant to this action and they have sought documents from KPMG from a limited time period. Once again, however, KPMG ties its argument back to Congress intent in enacting the statutory privilege, an issue the Court need not address to resolve the present motion. Indeed, the plain language of the statute makes clear that Congress did not create a blanket privilege regarding the PCAOB inspection process. Given that KPMG has already produced documents in this litigation and that Plaintiffs requests at issue in this motion are limited in time and scope, KPMG has not demonstrated that the subpoenas are unduly burdensome. Furthermore, Plaintiffs have agreed to reimburse KPMG for reasonable production and copying costs. (R. 261, Pls. Oppn, p. 14.) Finally, given that Plaintiffs have only requested to take the depositions of two KPMG professionals, the Court does not find that the deposition requests are unduly burdensome either. Finally, KPMG objects to the production of a privilege log. KPMG asserts that it need not produce a privilege log because Section 105(b)(5)(A) places the materials to which it applies beyond the reach of discovery. (R. 268-1, KPMGs Reply, p. 14.) Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 45(d) (2)(A), however, expressly provides that: A person withholding subpoenaed information under a claim that it is privileged . . . must: (i) expressly make the claim; and (ii) describe the nature of the withheld documents, communications, or tangible things in a manner that, without revealing information itself privileged or protected, will enable the parties to assess the claim. Fed. R. Civ. P. 45. Because KPMG has asserted a statutory privilege, it must provide Plaintiffs with a privilege log identifying the nature of the documents it contends are subject to the privilege.3

The Court declines to follow the holdings of the two district courts outside of Illinois cited by KPMG in its reply brief for the proposition that a log identifying the withheld documents by category is sufficient.

07C4507 Silverman vs. Motorola, Inc et al. Page 5 of 6

Case: 1:07-cv-04507 Document #: 294 Filed: 06/29/10 Page 6 of 6 PageID #:8711 CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, the Court denies KPMGs motion to quash or for protective order. KPMG must produce all documents regarding the accounting and disclosure of the 3Q06 transactions that were not prepared . . . specifically for the Board to Plaintiffs by July 13, 2010. KPMG must also produce a privilege log to Plaintiffs that describes the nature of any documents that it has withheld pursuant to Section105(b)(5)(A).

07C4507 Silverman vs. Motorola, Inc et al.

Page 6 of 6

You might also like

- Scott London Court FilingDocument16 pagesScott London Court FilingCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Suddeth Disciplinary OrderDocument8 pagesSuddeth Disciplinary OrderCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- PCAOB Broker-Dealer Audit Report Aug 19 2013Document44 pagesPCAOB Broker-Dealer Audit Report Aug 19 2013Caleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- 2013 PWCDocument33 pages2013 PWCCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- 2013 KPMGDocument34 pages2013 KPMGCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- CPAexam Passrates 2013q3Document1 pageCPAexam Passrates 2013q3Caleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Disciplinary Action DeloitteDocument13 pagesDisciplinary Action DeloitteCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Illustrative Audit OpinionDocument6 pagesIllustrative Audit OpinionCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- KPMG Advisory CompDocument2 pagesKPMG Advisory CompCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- 2013 PPEDD PromotionsDocument20 pages2013 PPEDD PromotionsCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- PCAOB 2012 Annual ReportDocument66 pagesPCAOB 2012 Annual ReportCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- 2013 Deloitte Touche LLP 2012Document19 pages2013 Deloitte Touche LLP 2012Caleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- EY 2012 Inspection ReportDocument29 pagesEY 2012 Inspection ReportCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- 2010 Pcaob EyDocument27 pages2010 Pcaob EyCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Crowe Horwath LLP 2012Document19 pagesCrowe Horwath LLP 2012Caleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- MOU ChinaDocument8 pagesMOU ChinaCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- London ComplaintDocument27 pagesLondon ComplaintCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Mike Lynch Open Letter To HPDocument2 pagesMike Lynch Open Letter To HPWSJTechNo ratings yet

- AICPA Peer ReviewDocument3 pagesAICPA Peer ReviewCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Gottlieb V EchevarriaDocument19 pagesGottlieb V EchevarriaCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- KPMG Pcaob 2012Document31 pagesKPMG Pcaob 2012Caleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- 2011 Gillibrand TaxesDocument24 pages2011 Gillibrand TaxesCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Information For Audit Committees About The PCAOB Inspection Process (Aug. 1, 2012)Document26 pagesInformation For Audit Committees About The PCAOB Inspection Process (Aug. 1, 2012)Vanessa SchoenthalerNo ratings yet

- Ifrs Work Plan Final ReportDocument137 pagesIfrs Work Plan Final ReportCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Big 4 BootcampDocument5 pagesBig 4 BootcampCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- PWC ARCDocument28 pagesPWC ARCCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Big 4 BootcampDocument5 pagesBig 4 BootcampCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Motion To Dismiss - Horowitz v. GMCRDocument46 pagesMotion To Dismiss - Horowitz v. GMCRCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- Rita A. Crundwell - Horse InventoryDocument10 pagesRita A. Crundwell - Horse InventorysaukvalleynewsNo ratings yet

- 2012 Grant Thornton LLPDocument26 pages2012 Grant Thornton LLPCaleb NewquistNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Case 1.1 Enron CorporationDocument13 pagesCase 1.1 Enron CorporationAlexa RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Internal Control Checklist - NPODocument30 pagesInternal Control Checklist - NPOJennylyn Favila MagdadaroNo ratings yet

- Notes in Organization and Functions of The BirDocument5 pagesNotes in Organization and Functions of The BirNinaNo ratings yet

- Raccon BookmarkDocument2 pagesRaccon BookmarkLinda YiusNo ratings yet

- 700.1. Pharmacy Operation Management Print 1Document11 pages700.1. Pharmacy Operation Management Print 1ozokwelu ebereNo ratings yet

- Legal Liability of Cpas: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument23 pagesLegal Liability of Cpas: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinWenJiangNo ratings yet

- Management Accountant March-2016Document124 pagesManagement Accountant March-2016ABC 123No ratings yet

- Tugas Teori Akun 17 NoDocument9 pagesTugas Teori Akun 17 NonerissaNo ratings yet

- CV - Joan BonifacioDocument2 pagesCV - Joan BonifacioNitaiGauranga108No ratings yet

- VIVADocument15 pagesVIVAAlex MoonNo ratings yet

- Prospectus FullDocument358 pagesProspectus FullRiazboniNo ratings yet

- Form Gstr-9C: CA Pratik Sudhir Shah, 9819122318Document54 pagesForm Gstr-9C: CA Pratik Sudhir Shah, 9819122318K SwaroopNo ratings yet

- Bondor Steel PDFDocument63 pagesBondor Steel PDFriad riduNo ratings yet

- ISO 17065 NotesDocument36 pagesISO 17065 Notesnene_jmlNo ratings yet

- Le Rapport Du PAC Rendu PublicDocument50 pagesLe Rapport Du PAC Rendu PublicL'express Maurice0% (1)

- Project AppraisalDocument10 pagesProject AppraisalVenkatesh WarNo ratings yet

- Acctg 11A Financial Accounting and Reporting Partnership Accounting 3Document3 pagesAcctg 11A Financial Accounting and Reporting Partnership Accounting 3Sofia Lynn Rico RebancosNo ratings yet

- Secretary Certificate For GAMODocument3 pagesSecretary Certificate For GAMOshammahadelie1612No ratings yet

- Illustrative Assurance Report NBYL20150831 CleanDocument12 pagesIllustrative Assurance Report NBYL20150831 CleanLaurenNo ratings yet

- Advanced Management Accounting PDFDocument204 pagesAdvanced Management Accounting PDFptgo100% (1)

- (Sample) Law Bomb 2.0 (CA Inter) by CA Ravi AgarwalDocument18 pages(Sample) Law Bomb 2.0 (CA Inter) by CA Ravi AgarwalRishabh RudraNo ratings yet

- Sabp J 510Document7 pagesSabp J 510KrishnamoorthyNo ratings yet

- FPSC Senior Auditor PDF MCQs Book Free Download by AdspkDocument6 pagesFPSC Senior Auditor PDF MCQs Book Free Download by AdspkJaved Akhter67% (3)

- AuditeurDocument2 pagesAuditeurMed Khalil FarhatNo ratings yet

- RayeesDocument52 pagesRayeesAnshid ElamaramNo ratings yet

- Verification ReportDocument79 pagesVerification ReportajaydeshpandeNo ratings yet

- MFY Safety PDFDocument1 pageMFY Safety PDFSuadNo ratings yet

- CFO Controller VP Finance in Philadelphia PA Resume Brian PickettDocument2 pagesCFO Controller VP Finance in Philadelphia PA Resume Brian PickettBrianPickettNo ratings yet

- Focus Notes Philippine Framework For Assurance EngagementsDocument6 pagesFocus Notes Philippine Framework For Assurance EngagementsThomas_Godric100% (1)

- Pitch Deck Template EnglishDocument21 pagesPitch Deck Template EnglishlepaqueNo ratings yet