Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Housing and "Nance in Developing Countries: Invisible Issues On Research and Policy Agendas

Uploaded by

Mai A. Sultan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

34 views25 pagesHousing and "nance in developing countries: invisible issues on research and policy agendas. This paper considers the relationship between "nance and the livelihood strategies that households adopt in order to ful"l their housing needs. Housing "nance has risen to the top of urban policy and research agendas in recent years.

Original Description:

Original Title

12

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHousing and "nance in developing countries: invisible issues on research and policy agendas. This paper considers the relationship between "nance and the livelihood strategies that households adopt in order to ful"l their housing needs. Housing "nance has risen to the top of urban policy and research agendas in recent years.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

34 views25 pagesHousing and "Nance in Developing Countries: Invisible Issues On Research and Policy Agendas

Uploaded by

Mai A. SultanHousing and "nance in developing countries: invisible issues on research and policy agendas. This paper considers the relationship between "nance and the livelihood strategies that households adopt in order to ful"l their housing needs. Housing "nance has risen to the top of urban policy and research agendas in recent years.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 25

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: k.datta@qmw.ac.uk (K. Datta).

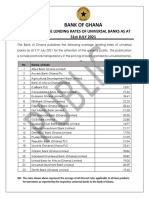

The World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank and USAID have led the shift from housing to "nance projects.

Bank lending for housing "nance commenced in 1983, and quickly accelerated so that by 1988 it exceeded that for

sites-and-service programmes for the previous 16 years and, by 1989, accounted for one-half of all urban lending

(Buckley, 1996).

Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

Housing and "nance in developing countries: invisible issues

on research and policy agendas

Kavita Datta*, Gareth A. Jones

Department of Geography, Queen Mary, University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, UK

London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK

Received 19 June 2000; received in revised form 11 August 2000; accepted 18 October 2000

Abstract

Housing "nance has risen to the top of research and policy agendas in recent years. Yet, although our

understanding of the formal delivery of housing "nance has improved considerably, we know far less about

households' use and production of housing "nance. This is particularly apparent in the case of four &invisible'

issues: land markets, rental housing, the role of savings and residential mobility. Drawing upon evidence

from Botswana and Mexico, this paper considers the relationship between "nance and the livelihood

strategies that households adopt in order to ful"l their housing needs. On the basis of this discussion, the

paper concludes by advocating a broader focus for housing "nance-related research. 2001 Elsevier

Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Housing "nance; Research agenda; Botswana; Mexico

1. Introduction

Housing "nance has risen to the top of urban policy and research agendas as the argument that

correctly structured "nance systems can deliver improved housing has gained purchase (Buckley,

1996; Malpezzi, 1990; Renaud, 1999; World Bank, 1993a). This constitutes a &second-generation'

approach to housing problems based upon an almost universal consensus among researchers and

national/international agencies that site-and-services projects and mass &public' construction

0197-3975/01/$- see front matter 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 1 9 7 - 3 9 7 5 ( 0 0 ) 0 0 0 3 8 - 2

` Slum upgrading, however, remains at the centre of many country and international agency urban projects despite

evaluations showing an inability to recover &hidden costs' through taxation, high rates of displacement, problems of land

acquisition and tenure, limited intervention by secondary lenders and community apathy (Werlin, 1999). Often noted, but

rarely written about in detail, upgrading involves a raft of "nance measures to retain a!ordability for households and

motivate consolidation and present agencies with administrative headaches.

` For country-speci"c examples see: Buckley (1996) on Argentina, Colombia, Poland and Hungary; Daniere (1999) on

Bolivia; Klak and Smith (1999) on Jamaica; Rakodi (1995a) on Zimbabwe; Siembieda and LoH pez Moreno (1999) on

Mexico; USAID (1997) on Poland and Valenc7 a (1992) on Brazil.

" For discussions of NGO-backed housing "nance schemes see: Bolnick and Mitlin (1999) on South Africa;

Cabannes (1997) on Brazil; Ferguson (1999) and Richmond (1997) on Bolivia; Lee (1995) on Philippines; Patel (1999)

on India and Vakil (1996) on Zimbabwe. Brief synopses of other schemes can be found in HiFi News, the Newsletter of

the Working Group on Housing Finance and Resource Mobilisation published on behalf of Habitat International

Coalition.

` For reviews of experience see: Ferguson et al. (1996) for Latin America, Rojas (1999) for Chile and Gilbert (1997)

for Colombia. Often associated with a neo-liberal approach, housing subsidy programmes have entailed

considerable public sector involvement, even in Chile where the government determines almost 60% of housing delivery

(Rojas, 1999).

" As shown by these studies, subsidy programmes in Chile and South Africa have built housing in locations distant

from employment, infrastructure and set up substantial future maintenance costs, while research in India has shown how

highly subsidised upgrading programmes can produce unsustainable &"nance gaps' for low-income households.

programmes have been ine!ective at resolving the housing crisis in developing countries.` It is

supported by evidence to show that housing policies based on &cheap "nance' such as interest rate

subsidies distort both housing and "nance markets, lead to reduced and inequitable housing

supply, and put pressure on "scal balances and exchange rates (Buckley, 1996; Malpezzi, 1990;

Mayo, 1999).` Consequently, some governments have reformed both public "nance institutions to

make them more prudent and regulatory regimes to encourage private "nance institutions to go

down-market (Boleat, 1987; Buckley, 1996; Okpala, 1994; Renaud, 1999; UNCHS, 1991b). Steps

have also been taken to enable the integration of formal and informal "nance through &third-way'

approaches involving community banks, NGO-backed group schemes and public partnerships

(Ferguson, 1999; Jones & Mitlin, 1999; Mitlin, 1997a; Sida, 1997; UNCHS, 1993)." Together with

policies aimed at strengthening urban management and governance, these &new' directions in

housing and "nance form the centrepiece of a range of international policy agendas including the

Habitat II Global Plan for Action.

In contrast to the policy innovation and research into the supply side of housing "nance, our

understanding of the demand side of the equation appears to be far less advanced. The principal

exception to this is the research into end-user housing subsidies which has argued in favour of

targeted one-o! grants to stimulate demand for formal housing among the poor (Buckley, 1996;

Mayo, 1999).` Analyses of housing subsidies have, however, alerted policy makers to the possibility

that programmes have not been designed with su$cient sensitivity to household needs, are not as

socially progressive in practice as they might appear on paper and may be leading some households

into new forms of poverty (Baken & Smets, 1999; Ferguson, Rubenstein, & Dominguez-Vial, 1996;

Gilbert, 1997, Jones & Datta, 2000; Mayo, 1999; Rojas, 1999)." Other studies have questioned the

advocacy for large single loans or subsidies for the delivery of immediate occupancy housing units

with debt paid over 10}20 years.

334 K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

` The literature on asset frameworks has two features. First, it refers mostly to established settlements, often

20}30-years old, that have organised communities, more readily identi"able networks and evidence of the bene"ts of trust

and participation. Second, it seems to assume that housing is already built or even quite well consolidated, leading to

discussion on home-based enterprises, and not about the debt and obligations required to "nance construction.

` Fieldwork in Botswana consisted of interviews with 210 tenant households and 86 owner households living in four

low-income settlements in Gaborone in 1992; 112 sharer households in 1995 and archival study and further interviews

with policy makers and NGOs in 2000. Fieldwork in Mexico consisted of questionnaires with 446 households in 11

low-income settlements in the cities of QuereH taro and Toluca.

In order to reach the poorest households with minimum disruption to domestic budget

strategies, researchers and NGOs have argued that the provision of "nance should be sensitised to

the housing process (Anzorena et al., 1998; Baken & Smets, 1999; Merrett & Russell, 1994; Patel,

1999; Smets, 1999). The key principles must be to provide &housing "nance' incrementally and in

ways that support urban livelihoods and asset formation rather than increase vulnerability through

debt, and which build social capital rather than individualism and mistrust. These principles

present clear parallels with wider debates concerning urban livelihoods, capabilities, access, and

asset frameworks (Moser, 1998; Rakodi, 1999; UNDP, 1995; Wegelin, 1999; World Bank, 2000) and

how to &release' the value of informal sector housing through property registration and micro-

"nance (de Soto, 2000). Yet, despite a language in the urban livelihoods literature that casts the

poor as managers of &assets' or &portfolios', the signi"cance of housing and land as the most

valuable (and costly) asset which most low-income households will ever acquire, and the size of

&housing' "nance relative to household budgets, little research has attempted to draw explicit links

between housing "nance and poverty alleviation.` In order to draw out this link we need to know

more about how households produce and use "nance to meet their housing needs.

In this paper our aim is to think through and across existing research and policy on housing and

"nance in developing countries, concentrating on four issues which appear to be largely invisible

on current agendas: land markets, rental housing, savings and residential mobility. Dealing with

these sequentially, we argue that research and policy on housing "nance has continued to

emphasise a &housing' problem rather than one of land market access which is the initial di$culty

many low-income households face when attempting to acquire urban shelter. In light of this, we

seek to illustrate how these households have "nanced the acquisition of land and what role "nance

can play in overcoming a perceived land access/a!ordability crisis. Second, research and policy has

also reinvented a long-standing bias against rental housing despite a recognition that this sector

continues to house signi"cant numbers of the lowest-income households in developing countries.

We examine how tenants have coped without recourse to formal "nance. Third, in a literature

dominated by information on accessing "nance as credit, we know relatively little about the role of

savings as part of household strategies to acquire/consolidate housing. Lastly, many policy makers

and researchers have argued that residential mobility is an important indicator of e$cient housing

and "nance markets. We consider the evidence for residential mobility and what might be the

expected impact of more widely available "nance. Our arguments are illustrated throughout by

evidence from Botswana and Mexico.` The paper concludes by advocating a broader focus for

housing "nance-related research.

K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357 335

" Despite the attention to land price changes, few empirical studies were carried out that took account of urban

expansion (rather than a single settlements' growth over time), adjusted for general in#ation and unpacked the changing

composition of household income. The more rigorous studies tended to note that land prices were #at or cyclical over the

medium term, and trends were stable: see Pamuk and Dowall (1998) for Trinidad, Sabatini (2001) for Chile and Ward et

al. (1993) for Mexico.

" Similar audits have been conducted for land development in Malaysia and Thailand (Dowall & Clark, 1996; World

Bank, 1993a) and Peru (de Soto, 1986). Hernando de Soto's Institute of Liberty and Democracy is currently conducting

audits of government regulations and procedures in Egypt, Russia, Haiti and Philippines.

The exceptions are Dowall and Leaf (1991) on Indonesia, Pamuk (1998) and Pamuk and Dowall (1998) on Trinidad,

Thirkell (1996) on the Philippines and Ward et al. (1993) on Mexico.

2. Finance and access to land

During the 1980s, research highlighted a series of worrying trends in urban land markets in

developing countries. Land markets appeared to be increasingly commodi"ed such that &social' or

&customary' forms of land access were observed to be in decline, opportunities for land invasion

were more limited, and governments were either having di$culties assembling land reserves or

were selling what land they did hold to private developers. Within the overall context of falling

incomes due to economic crisis and structural adjustment, the relationship between the cost of land

and income levels was looked at with some reports suggesting growing or impending a!ordability

problems (UNCHS, 1996)."

In response to these trends, researchers and policymakers have concentrated upon measures to

improve the e$ciency or productivity of urban land markets. The role of government has been

particularly scrutinised with research emphasising that intervention in land markets has resulted in

unnecessary regulations, encouraged the holding of land rather than its development, and sti#ed

the ability of developers to go down-market (Azizi, 1998; de Soto, 1986; Dowall & Clark, 1996;

Malpezzi, 1994; Strassmann & Blunt, 1994). A vivid illustration is provided by a number of East

African countries where the formal acquisition of land requires no less then 33 steps that can last up

to three years (UNCHS, 1996)." It is argued that the almost universal outcome of such over-

bureaucratisation is illegal land transactions (de Soto, 1986). To overcome such &state failure', and

in concurrence with the view that governments should be enablers, regulatory frameworks that

promote e$cient land conversion, secure property rights and facilitate transactions have been

formed (Malpezzi, 1994; World Bank, 1993a). Countries that have liberalised their regulatory

regime, such as Chile and Thailand, are regarded as having more e$cient land markets although

demand still outstrips supply (Dowall & Clark, 1996; Malpezzi, 1994; Sabatini, 2001).

The validity of such views not withstanding, researchers have paid much less attention to the

relationship between land markets and "nance such that most governments, international

agencies and NGOs interpret "nance to mean &housing' "nance. One consequence of this narrow

focus is the problems encountered by housing subsidy programmes in terms of land acquisition

that have resulted in &a!ordable housing' being located at the urban periphery distant from major

infrastructure, transport and employment (Jones & Datta, 2000; Rojas, 1999; Sida, 1997). Another

consequence is that assessments of the land market}government regulation relationship have

tended to focus on the formal supply of land and the level of prices, and not what is happening to

the informal supply of land or how households maintain levels of a!ordability (Jones, 1996). How

336 K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

` The questionnaires were conducted by Jones and Edith JimeH nez from a random sample of plots in 11 low-income

settlements. All but two of the settlements were formed illegally although some had embarked upon &legalisation' by the

time questionnaires were undertaken. Six settlements were formed on what is known as ejido land, a form of community

or social tenure that cannot be sold legally. Instead, some communities obscured this transaction by appearing to cede

land to occupiers by making them their heirs or community members. Questionnaires were only conducted with

households that had acquired a plot of land without an existing construction and rarely with services.

` There are a number of explanations to this "nding. First, the category includes &non-response' to the questions.

Second, some plots were acquired &free' in the older and mostly ejido settlements, and in one other settlement formed by

invasion, sometimes as a return for social obligations. Third, some households probably held cash during the period of

searching for a plot and did not identify this money as savings.

" With rapid in#ation during the 1980s and falling real incomes, it was unwise to keep savings as cash or in credit

rotation schemes which decapitalise rapidly. Instead, households maintained a broad range of savings mechanisms

including animals, cars or consumer goods.

have low-income households "nanced the acquisition of a plot of land and what role can "nance

perform in overcoming an actual or potential land access-a!ordability crisis?

Data from questionnaires conducted in the Mexican cities of QuereH taro and Toluca provide

some insights to these questions.` These data show that 82% of households bought land, 9%

acquired land through invasion and 8% were ceded the land (with or without a nominal payment)

from ejido authorities. Looking in detail at how "nance was assembled for the land acquisition

process reveals that 27% of households reported making no "nancial arrangements.` Of the 324

households that could explain how land access was "nanced, 16 methods of "nance were identi"ed.

These can be divided into external sources that included loans from employers, advance use of

pension funds, participation in a rotating credit scheme (tanda), borrowing from a local priest or

moneylender, and internal sources that included the sale of furniture or animals, gifts, extra jobs

and short-term overtime." Households were asked about which source was the principal and

secondary form of "nance for plot acquisition. Against the assumption that households in self-help

settlements possess savings to get them started, Table 1 indicates that external "nance is more

common than internal "nance. Moreover, these external funds were insu$cient to prevent 97

households (30%) from requiring a secondary source of "nance which for 55% of households was

also from an external source.

The data also suggest that households drew upon sources of "nance according to land market

conditions. In general, land prices were higher in Toluca than in QuereH taro (Ward, JimeH nez,

& Jones, 1993). This is re#ected by the data in a number of di!erent ways. First, proportionally

more households in Toluca were able to identify "nance as important to plot acquisition: 169

households in Toluca (86% of sample) compared to 155 households in QuereH taro (62% of sample).

Second, proportionally more households in Toluca identi"ed a secondary source of "nance

compared to those in QuereH taro: 71 (42% respondents) versus 26 (17% respondents). Third, while

a higher proportion of households able or willing to discuss sources of "nance in QuereH taro

identi"ed an external principal source of "nance (64% compared to 53%), of all households in the

sample those in Toluca were more dependent upon external "nance (46% compared to 40% in

QuereH taro). Households in the city with the highest land prices, therefore, were more aware of

"nance, were more likely to use more than one source and that source was more likely to be

external to the household.

K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357 337

Table 1

Financial mechanisms for plot acquisition in QuereH taro and Toluca, Mexico

QuereH taro Toluca

Principal source Secondary source Principal source Secondary source

Internal mechanisms 56 (36%) 9 (35%) 79 (47%) 35 (49%)

External mechanisms 99 (64%) 17 (65%) 90 (53%) 36 (51%)

All "nancial mechanisms 155 (62%) 26 (10%) 169 (86%) 71 (36%)

` Households were not asked to ascribe an amount nor to distinguish between principal and secondary sources of

"nance as more than one method was sometimes used for payment. Therefore, the text refers to &cases' and not

&households'.

" The availability of phased payment is encouraged by sellers and seems to di!er with the level of land prices. In both

cities, plot acquisition by payments only was available in two settlements, Lomas de Casa Blanca and Pen uelas in

QuereH taro and Seminario and San Buenaventura in Toluca. But sellers were more insistent upon a deposit in Toluca

where payments and deposit was encouraged in Nueva Oxtotitlan, San Buenaventura and Seminario compared to only

one settlement in QuereH taro, Pen uelas.

The relationship between land market conditions and access to "nance dictated the ability of

households to adapt payment schedules to a!ordability pressures. Households were asked a series of

open-ended questions to match the sources of "nance to the method of payment for plot acquisition.

In total, 324 households identi"ed 405 combinations of external and internal "nance.` The results

are shown in Table 2 and reveal that "nance was most commonly used to acquire a plot in a single

payment (188 cases) for which households were borrowing or selling household items. We do not

know whether households believed land prices were rising (and therefore that they needed to move

fast to secure a plot), or whether sellers were unwilling to o!er alternatives to single payment or

households preferred to avoid owing money to sometimes unscrupulous land sellers. Looking at the

breakdown of the method of payment by settlement does indicate that when phased payments were

on o!er they were taken up."

Again, there appears to be a marked di!erence between the two cities. In QuereH taro, which had

lower land prices, households were more likely to purchase a plot in a single payment (104 cases

compared to 84 in Toluca). However, they were also more likely to use an external source of "nance

for the single payment (70 cases, 41% of 169 cases) compared to those in Toluca (44 cases, 19% of

cases). In Toluca, plot acquisition was possible through phased payments which required external

"nance in 60 cases and an identi"able source of internal "nance for 52. By comparison, in

QuereH taro, both external and internal sources of "nance were used to maintain payments in only 40

cases. In Toluca, therefore, the higher price for land meant that "nance was used to spread

payments, which might also allow in#ation to depreciate the real value of each payment and &buy'

the household time to accumulate resources for subsequent instalments (Ward et al., 1993).

The data show the motivation of households to mobilise a range of "nance mechanisms in order

to both cover a "nance-gap between price and income, but also to minimise the total land

338 K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

Table 2

Purpose of external and internal "nance in quereH taro and Toluca, Mexico

QuereH taro Toluca Total

External

mechanisms

Internal

mechanisms

External

mechanisms

Internal

mechanisms

Single payment 70 (65%) 34 (55%) 44 (35%) 40 (36%) 188 (46%)

Deposit 12 (11%) 9 (15%) 9 (7%) 9 (8%) 39 (10%)

Payments 24 (22%) 16 (26%) 60 (48%) 52 (46%) 152 (38%)

Deposit & payments 1 (1%) 0 11 (9%) 11 (10%) 23 (6%)

Other 0 3 (5%) 0 0 3 (1%)

Total 107 62 124 112 405

` This trajectory tends to be represented as a binary between ownership and rental. However, research shows the

diversity of the rental sector (Gilbert & Varley, 1991; Rakodi, 1995b) and of ownership (Miraftab, 1997; Thirkell, 1996)

due in part to the increasing importance of inheritance (Tipple et al., 1997). All categories su!er from problems of

de"nition and data, especially the less researched aspects of the rental sector such as &rent-free' tenancy which may mask

contributions to household bills, childminding duties or guardianship of a house or plot while settlement security is

established (Datta, 1996, 1999).

acquisition period. Using a combination of "nance sources and methods of payment, 420 house-

holds were able to pay for the plot within 12 months of the purchase being agreed. A further 15

households took under 5 years and only three households more than "ve. Based on our data it is

clear then that low-income households in Mexico generally are averse to long-term debt and

employ an innovative range of "nance sources in order to acquire land. Having acquired a plot of

land, however, it is notable that many households took many months before construction and

occupation took place.

The means by which households produce and use "nance to gain access to land may set down

direct consequences for the "nance of housing. Clearly, therefore, we need to understand "nance for

land and housing, and the relationship between land and housing markets. As we discuss below,

examination of this relationship needs to consider housing "nance beyond ownership.

3. Finance and rental housing

A recent UNCHS study found that tenants accounted for 30% of the urban population in 16

countries rising to 50% in a further eight, while an examination of older World Bank sponsored

urban projects found that 20}40% of houses were partially or wholly rented (Kumar 1996;

UNCHS, 1996). Yet, urban policy often explicitly and implicitly represents the tenure trajectory of

low-income households as a one-way process from renting/sharing to owning with the latter seen

as the &normal' goal of households (Barbosa, Cabannes, & Mora es, 1997; Datta, 1996; Gilbert,

1993, 1999; Rakodi, 1995b).` At the same time, research with tenants shows that they too expect

K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357 339

` It is hardly surprising then that the majority of tenants interviewed in 1992 expressed a desire to be owners with

many of them having already applied for plots through the SHHA.

" A literature review revealed few examples of NGOs working exclusively or equally with tenants through housing

"nance programmes. Some exceptions are the Goiania State Federation of Tenants and Posseriros, Brazil, that

represents both tenants and owners, the Pagtambayayong Foundation in Cebu City, Philippines, that has explored the

feasibility of providing commercial loans to low-income owners to extend and let part of their homes, and one NGO in

Bolivia that has worked speci"cally with tenants in a housing "nance project (Barbosa et al., 1997; Mitlin, 1997b;

Richmond, 1997).

`" This is illustrated in the case of Botswana by the Integrated Pilot Poverty Alleviation and Housing Schemes initiated

in June 1999 which aim to train very low-income households in both the development of microenterprises and the

construction of a!ordable housing (Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, 2000).

&today's tenants to be tomorrow's owners', believing rental to be a temporary housing solution and

exhibiting an almost universal desire for ownership (Datta, 1995; Gilbert, 1993; van Lindert, 1992).

This representation fails to note that the attractions of ownership are * to some extent

*&constructed' by government support through subsidies on services and building materials, &right

to buy' policies, and pronouncements that ownership is a sound investment (Datta, 1995; Merrett

& Russell, 1994; UNCHS, 1991b). This is well illustrated in the case of urban Botswana where the

Self-Help Housing Agency (SHHA), set up in 1976, has had the sole remit to provide housing for

ownership to low-income households. Until the early 1990s, the SHHA encouraged the expansion

of home-ownership through the provision of (almost) free land, subsidised building material loans

and service charges, and failed to re-possess the properties of defaulters leading to the curious

situation whereby formal sector ownership was cheaper than informal renting.` Such an o$cial bias

towards ownership has continued into almost all second generation housing subsidy programmes

that are based upon new build projects: in Chile, subsidies for rent form a small proportion of total

allocations and South Africa's programme omitted renters in its early stages (Jones & Datta, 2000;

Rojas, 1999). Moreover, this marginalisation of the rental sector also applies to NGO-backed

projects despite their supposed attention to poverty alleviation, advocacy of empowerment for

excluded groups and, in some cases, resistance to the ideology of individual ownership."

There are three reasons why the marginalisation of the rental sector by housing "nance policy is

problematic. First, the suggestion that &today's tenants are tomorrow's owners' is based upon an

assumption that the conditions that have produced access to ownership for large numbers of

households in the past will remain unchanged. Yet, research in many countries illustrates that the

constituent elements of housing (especially land and building materials) have been subject to

commodi"cation and prices may increase above income (UNCHS, 1989, 1996, but see endnote 9).

Certainly data from Botswana show that access to ownership is becoming harder and that

correspondingly the period spent in rental housing may not be as temporary as assumed (see

below). Support for the rental sector, therefore, may relieve some of the pressure on segments of the

housing and land markets, and mitigate against the worst aspects of overcrowding that can be one

result of market failure.

Second, the invisibility of rental housing is problematic given that new research and policy

agendas aim to draw speci"c links between e$cient housing markets and poverty reduction

(Wegelin, 1999).`" Thus understanding the rental sector, which includes a high percentage of the

poorest households living in &backyard shacks' as &sharers' or on family compounds &rent-free', is

340 K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

` The information presented here was collected by Datta in 1992, 1995 and 2000 and enables us to track changes in the

housing market, and the rental sector in particular, over a fairly long time period.

`` Even in 1991, 58% of self-help housing occupants were tenants and 60% of owners let rooms (Central Statistics

O$ce, 1991).

`` The same might not apply to owners who used the petty rental market as part of a strategy to cover a &"nance-gap'

on their own housing (Datta, 1999). Elsewhere, in Bolivia, India and Nigeria, tenants are an important source of housing

"nance providing owners with a lump sum that may be used to cover the "nancial cost of building rental units. In return

the tenant can live in the property rent-free for an agreed period after which the lump sum may be returned without

interest (Baken & Smets, 1999; Ikejiofor, 1997; Richmond, 1997).

more not less important (Gilbert, 1993; Gilbert, Mabin, McCarthy, & Watson, 1997; Rakodi,

1995b; Tipple, Korboe, & Garrod, 1997). The nexus of housing access, poverty and gender also

means that rental housing is especially signi"cant for women-headed households who form

a disproportionate number of tenants in many cities (Chant, 1997; Falu & Curutchet, 1991; Gilbert,

1993; Miraftab, 1997). While it is increasingly debated that the relationship between gender and

poverty does not hold in all contexts, it remains the case that signi"cant proportions of women are

relatively poorer then men (Datta & McIlwaine, 2000). Given that this &feminisation of poverty' is

often accompanied by the considerable discrimination women face in terms of their access to

formal (housing) "nance markets and thus ownership, the importance of rental housing is further

illustrated.

Third, ownership is not the desired form of tenure for all, at least in the short term. Certain types

of households and those in certain stages of the life cycle may prefer to rent. Research on

women-headed households, for example, shows that some women heads prefer to rent in central

city tenements which may o!er greater physical security, a wider range of support networks and

community acceptance of single mothers (Miraftab, 1997). Moreover, the pressure on women to

perform domestic and community roles may reduce the attraction of ownership in poorly serviced

peripheral settlements (Chant, 1996; Miraftab, 1997). It can be argued that the bias exhibited by

formal "nance organisations against the rental sector is, therefore, a bias also in favour of the

nuclear household and against women-headed households who may be most in need of assistance.

An appreciation of the importance of the rental sector takes us to two inter-related questions:

how have tenants coped with the non-availability of "nance to the rental sector and how might the

availability of "nance resolve some of the problems experienced by this sector? Drawing upon

longitudinal research conducted in Gaborone, Botswana, we take each question in turn.` Here,

our research illustrates the critical links between di!erent sectors of the housing market. The failure

of formal public and private organisations to satisfy the demand for home-ownership throughout

the 1990s, and the progressive stripping away of subsidies for ownership, has led to a steady

escalation in the demand for, and pressure on, alternative forms of tenure such as renting and

sharing.`` Correspondingly, the non-availability of "nance for rental housing has also become

increasingly problematic.

Pre-dating policy reforms which have blocked access to ownership and increased the pressure on

the rental sector, interviews with tenants in 1992 found that most tenants could meet the "nancial

costs of renting accommodation without recourse to either formal or informal "nance.`` This is

attributable to a range of reasons including the fact that all but 5% of tenants were in full-time

K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357 341

`" The evasion of rent was not easy as the majority of tenants lived on the same plot or even the same house as their

landlord while in other cases visits by landlords coincided with pay days. Cases of non-payment were more evident in

interviews with landlords one of whom complained that her tenants were a &headache' especially &when they ran out of

money and had to be asked to leave' (Datta, 1995).

`` The tenure histories of 41%of tenant households revealed a movement between rented and shared accommodation.

employment and rents at this time constituted between 9 and 25% of average incomes. Conse-

quently, tenants could "nance deposits, monthly rent or rent increases out of their savings. Thus,

although some tenants complained that rent increases made &their budgets tight', 73% of the

households interviewed reported that their rents were a!ordable. Moreover, and despite the

apparent self-su$ciency reported above, tenants were able to operationalise informal strategies

(such as rent evasion`" and sharing`` with relatives) in situations where the payment of rent did

become onerous. In general, most tenants were optimistic about their chances of becoming

homeowners and believed that the costs that they incurred while renting would be re-couped once

they became homeowners.

However, this optimism has faded in the face of newly enacted policies which have reduced the

range of subsidies available to &new' owners and created blockages in the ownership market. These,

in turn, are a product of the transition of the government from being a landlord, "nancier and

direct producer of housing to being an enabler working in partnership with other stakeholders

(Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, 2000). In its new role, the government has

particularly targeted land in its accelerated land development programme (ALDP). Under this

programme, the government has decided that plots previously provided &free' should be sold to

urban residents, albeit at what it considers to be &cost'. In 1999, it was estimated that the average

price of a low-income plot (between 370 and 400 m`) would be P11232-12600 (US$ 2458}2757)

(Datta, 1999). This single policy change has obviously had an immediate impact upon the

a!ordability of ownership as evidenced by the slow uptake of plots. Thus, despite the introduction

of a phased payment system whereby title deeds are granted once a 10% deposit had been paid and

an undertaking is made to pay the balance and develop the land within four years, 67% of

applicants face a!ordability problems (Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, 2000).

There is also evidence of increased default of payments with the recent re-possession of 427 plots by

the Ministry of Local Government, Lands and Housing with a further 500 repossessions pending

(Daily News, 22nd September 1999). Moreover, the land access-a!ordability crisis has further

deepened as allocation of residential plots has once again halted due to the non-availability of

serviced land.

The cumulative result of such policy changes has been that the tenure transition from renting to

ownership has been blocked and the housing market has become increasingly segmented. Block-

ages to ownership have meant that there is now an increased demand for non-ownership forms of

tenure such as renting. But, the current rental market bears little resemblance to the rental market

of a decade earlier and it is now that the non-availability of "nance is emerging as a signi"cant

issue. Heightened demand has resulted in an escalation in rent levels with some reports suggesting

that rents now consume over 50% of average income which are also under pressure from slower

economic growth (Daily News, 22nd September 1999). Consequently, tenants and prospective

tenants have had to formulate a variety of strategies to meet their housing needs. Again, sharing

with relatives in order to reduce housing costs is common, and interviews with sharers in 1995

342 K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

`" Illegal land transactions in Mogoditshane were the subject of a government investigation (the Kgabo Commission)

in the early 1990s which reported on illegal private sales of tribal land to outsiders mostly from Gaborone.

`` The exclusion of low-income tenants from the central city has been inadequately researched. It is unclear to what

extent exclusion is because housing is "ltering up as rent controls are removed and rehabilitation programmes take place,

or whether they have "ltered down to such an extent that units have become uninhabitable. At the periphery, the multiple

subdivision or rent of a plot in Latin America appears to be less common or takes place at a later stage in the

consolidation process than in Africa (see Gilbert & Varley, 1991; Kellet, 1992).

revealed an increased movement between sharing and renting compared to 1992. Given that the

trading of a rented room for shared space resulted in a decline in housing standards (with

respondents sleeping in kitchens/sitting rooms, sometimes with other sharers and/or the hosts'

children), it is unsurprisingly that most sharers interviewed in 1995 wanted to revert back to renting

as soon as possible.

Another strategy is to move outside of Gaborone to peripheral villages and towns in search of

more a!ordable rental accommodation or cheaper land. Indeed, the demand for land in peripheral

villages has been so high that the sub-land board of one village, Mogoditshane, froze the allocation

of plots in 1993.`" As a result, people have gone further a"eld in their search for land thus incurring

higher transport costs (Daily News, 22nd September 1999).

As a "nal strategy tenants have begun to participate in land invasions which occurred "rst in

peripheral villages in the early 1990s and have since become more common within Gaborone itself.

The mid-term review of the current national development plan cites squatting as one of the most

signi"cant problems facing the housing market (Ministry of Finance and Development Planning,

2000). In one invasion in August 1999, &vacant' (government) land was settled by about 1000 people

(including evicted tenants) on the premise that the only way out of paying high rents and of

becoming a homeowner was through the &self-allocation' of land. Although these squatters were

&cleared o!', the threat of land invasions looms large as evidenced by recurrent speeches by

prominent politicians on the need for people to be &patient', a parliamentary debate on the illegality

of land invasions and the formulation of a revised White Paper on Housing (Daily News, 10, 11 and

17 August 1999, Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, 2000). Political tensions have

further heightened in the face of more demolitions of squatter camps with opposition parties calling

for the resignation of the Minister of Local Government, Lands and Housing on the grounds that

he has failed to address the shortage of land and a!ordable accommodation (Mmegi wa Dikanag,

22}28 September 2000).

How might "nance be made available to resolve the housing problem in the rental sector? First,

perceptions of tenants as undeserving of assistance, especially when compared to &squatters' in the

under-serviced settlements at the periphery, need to be re-assessed. Although renting is still often

depicted as a central city problem, research shows that a high proportion of tenants actually live in

peripheral settlements (Bernardini, 1997; Datta, 1996; Gilbert & Crankshaw, 1999; Gilbert & Var-

ley, 1991; van Lindert, 1992; Tipple et al., 1997).`` The conventional position also holds that

tenants are an unattractive target of housing "nance, either because they will use the funds for

consumption purposes or to "nance the transition to ownership. These perceptions underestimate

the relationship between the rental sector and ownership, considering the former to be opposed to

the latter. In fact, it is necessary to acknowledge that the problem encountered by tenants or

prospective tenants in Gaborone is related to policies and the lack of "nance available to

K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357 343

`` However, research displays no consistent picture on the capital holding of tenants. Due to rural}urban, intra- and

transnational migration, it is dangerous to assume that all tenants are capital-less as many may own property elsewhere.

While the concept of a rural home may be in decline generally as a result of more permanent urban residence,

transnational labour markets in North Africa, the Middle East, Central America and the Caribbean have resulted in

investment through remittances to rural areas.

ownership. Improving the availability and a!ordability of land or housing to owners, therefore,

may have positive outcomes for tenants by releasing pressure on the rental sector and as owners

build rooms for rent (see next section).

Second, we need to acknowledge that the provision of "nance to the rental sector presents more

risk to lenders as the collateral (the house) is not owned by the borrower (the tenant). To cover such

risk either alternate forms of collateral need to be found or a premium added to interest rates. As

tenants are usually capital-poor`` and usually represent a signi"cant proportion of lowest-income

households such measures might be di$cult to establish and would likely be socially regressive.

One possible solution would be to adapt the informal saving and loan schemes that are commonly

used to smooth consumption costs (Johnson & Rogaly, 1997). An NGO, for example, might be able

to collect rent payments and provide an institutional guarantee to landlords of tenant good faith,

chasing defaulters if the need arises. The NGO might be able to negotiate rent discounts or attract

funds from government or donors to provide insurance against shortfalls in rent payment, and

perhaps for a small fee, could provide workshops to tenants on "nancial management, further

reducing risk to a landlord and lender.

A third possibility is to extend "nance either to increase the production or the quality of rental

housing. Targeting landlords so as to increase the supply of housing has been advocated for some

time (Gilbert, 1993; Ikejiofor, 1997), but the negative connotations of &landlordism' means that it is

advice that remains unheeded by international agencies, national and local governments. In

Gaborone and elsewhere, landlords may be as poor as their tenants and in need of such "nance

(Mitlin, 1997b; UNCHS, 1989). Providing assistance to landlords may be more sustainable than

lending for the purposes of ownership, as small landlords intend to gain an income from their

tenancies. Lending to landlords may also be more cost-e!ective and supply-elastic than existing

housing "nance programmes that concentrate upon &new build ' which need to assemble land and

install services. Moreover, collateral requirements are less problematic as existing structures may

be mortgaged (provided they meet the criteria of lenders) or a bond placed as guarantee against

rental income where land or housing tenure may be extralegal. Finally, lending to landlords may be

the most e!ective means to link housing "nance to poverty alleviation as additional rooms could

overcome the short-term housing crisis of low-income households, and the rental income could be

used to accumulate savings. We pursue this point further in the next section.

4. Self-help housing and the invisibility of savings

Most contemporary housing "nance related research and policy has concentrated upon how to

mobilise credit rather than how to encourage household savings. This is despite the fact that the

early writers on self-help housing were wary that credit payments could undermine a household's

344 K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

`" Important exceptions are Gough (1999) on Colombia, Baken, and Smets (1999) and Smets (2000) on savings in

rotating savings schemes in India, Macoloo (1994) on World Bank projects in Kenya, and Struyk, Katsura, and Mark

(1989) on Jordan.

`" What this means is that housing is "ltering up and higher quality housing for a constant income (Baer, 1991). While

not widespread, we have both encountered households during "eldwork that appear to live in better housing than their

present economic situation would suggest is feasible.

ability to reduce out-goings at times of crisis and debt would adversely e!ect the sense of security of

tenure. For Turner, for example, self-help housing was a!ordable precisely because it allowed

households to build in stages and so &synchronise investment in buildings and community facilities

with the rhythmof social and economic change' (Turner, 1967, p. 167). Turner did not argue against

recourse to external "nance. Indeed, he cited the establishment of a local housing "nance system as

a lasting achievement of his work in Peru (Turner, 1982, p. 101). Rather, self-help owners were

encouraged to save as a signal to potential lenders of their creditworthiness while being cautious

about how the transition from saving to borrowing was to be managed (UNCHS, 1991a).

In the three decades since Turner's groundbreaking work a considerable quantity of research has

supported links between housing consolidation and a host of variables such as income, age, and

tenure. But, little rigorous data has been presented on the costs of self-help housing, the relation-

ship between consolidation and the availability and management of di!erent types of "nance, or

indeed the role of savings.`" It is generally accepted that low-income households are not too poor

to save but that they do lack safe and convenient saving methods, and face problems from

institutions that insist upon minimum balances or do not o!er positive rates of interest (Johnson

& Rogaly, 1997). This limited institutional capacity suggests that many must hold savings outside

of the formal system (Boleat, 1987; Okpala, 1994). But, the precise mix of saving through consumer

items, jewellery and cash rotating schemes is rarely interrogated in relation to housing (Baken

& Smets, 1999; Merrett & Russell, 1994; Patel, 1999; Smets, 1999).

Of course, savings and housing are not separate. As Gilbert (1999) has pointed out, investment in

housing itself may serve as a surrogate form of saving. Households predict that housing is a reliable

store of value, especially as settlement consolidation takes place, even if the relatively small size of

the second-hand property market in some countries must make this a judgement based as much on

intuition as demonstration (Gilbert, 1999; Gough, 1998; Tipple et al., 1997). In Botswana, for

example, between 1976 and 1991, only 1827 (or 6.8% of all allocated plots) formally exchanged

hands of which 1010 ( just over 55%) were sold while the rest were gifts or part of an inheritance

(Ministry of Local Government, Land and Housing, 1992). Reliable information on land and

housing values is therefore hard to come by, and limited information on in#ation and alternative

investments make it di$cult to assess &real' trends. One question for research therefore is whether,

rather than save in order to build adequate housing as per conventional wisdom, the lack of

institutional "nancial capacity is increasing investment in housing as a form of savings. One could

even support a scenario that under certain conditions households may be &over' investing in

housing (compared to the alternative of income-generation for example), and that rather than

building an asset against risk, they may be increasing short term vulnerability (see Moser, 1998).`"

A renewed attention to the role of savings is important because of the changes to the housing

market. The present en vogue housing subsidy programmes are designed in the knowledge of

K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357 345

` Even in Chile, the attention to savings has not prevented a low take-up of subsidy allocations (55% in one

programme), high default rates and problems encouraging private institutions to move down-market (Rojas, 1999). By

comparison, in South Africa from 1994, the political expediency of the need to deliver subsidies down-market quickly and

equitably probably explains the absence of a saving requirement (Jones & Datta, 2000).

`` Note that in countries, such as Mexico, that underwent austerity measures earlier than Botswana and probably had

a more commodi"ed land and housing markets, external "nance was already important to gaining access to land by the

late 1980s.

`` The real value of the building material loan was always insu$cient to construct a house and fell over time as

building costs tripled during the 1980s, presenting even recipient households with a growing "nance-gap (Ministry of

Local Government, Lands and Housing, 1992). Arrears on these loans amounted to P4.8 million in December 1999 and

their recovery (made more di$cult by poor record keeping) is one of the main challenges facing the Self-Help Housing

Agency (Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, 2000).

a &"nance gap' and require demonstration of a saving history to receive a subsidy, despite our

limited understanding of how low-income households save.` We also need to incorporate changes

to the labour market and household composition. Before the late 1980s households could become

&owners' young in life having accumulated some savings which it was considered worthwhile to

devote to housing. Evidence gathered from Botswana through interviews with 86 owner house-

holds in 1992 revealed that savings were cited as the single most important source of "nance for

housing: 59% of all households interviewed had used savings both to enable new construction and

in order to consolidate dwellings. Most owners were relatively new urban dwellers and quite young

(early 30s), and there was a high proportion of women-headed households. However, subsequent

reforms have made employment less secure, made pension systems more expensive and exclusive,

and improved the collection of service charges and taxes. How then did the households interviewed

in 1992 acquire su$cient savings to build/consolidate their dwellings and what form did these

savings take? And, do today's households continue to become owners through savings and, to the

extent that they do, how do they amass these savings?``

First, until the early 1990s, households were assisted to save by the high level and widespread

subsidies provided by the government for land access, building materials and services cited above.

For example, building material loans from the Self-Help Housing Agency were provided at

a subsidised interest rate of 4% over 15 years, and arrears were rarely penalised. Not only did the

subsidies release income that could be saved but also the &soft' nature of the loans meant that many

households considered these as part of their saving portfolio rather than as debt.`` A second

component of &savings' was money from relatives, which was obtained by seven households in the

form of a loan. Although the precise conditions of repayment are unknown, the interviewees

seemed not to distinguish between the loans and gifts which is consistent with the "ndings of other

research (Baken & Smets, 1999).

The third, and most signi"cant, component of savings was rental income. Again, owners were

reluctant or unable to distinguish rental income from saving which is perhaps attributable to

a general perception that they were providing a service by letting rooms rather than involved in

pro"teering. A total of 56 of the 86 owners let rooms: on average three rooms were let but rose to

a maximum of 14. The time lag between the acquisition of a plot and the letting of a room was

7 years, suggesting that renting was not an option until the initial core house was consolidated, and

possibly re#ecting an increase in average incomes during the 1980s. However, subsequent rooms

346 K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

`" The geographies of these movements were obviously not replicated in all cities as some did not have inner city rental

areas while in others public housing was inaccessible to recently arrived migrants.

`` Indeed, there is an explicit prohibition on mobility in many upgrading programmes to prevent down-raiding and to

foster community participation (Werlin, 1999). Unfortunately, such measures often forced households to sell illegally

(Macoloo, 1994).

were added in a much shorter period of time illustrating the importance of rental income to

housing consolidation and adaptation to slower economic growth: room construction appeared

to coincide with the rent increases reported by tenants and almost all owners stated that renting

was &good business'. Some owners let the more &modern' rooms built initially for their own use but

which fetched higher rents, and often remained in temporary structures themselves.

In sum, government intervention in the ownership market resulted in low initial costs of

ownership. Given this and the permitted time lag between the acquisition of a plot and subsequent

construction, it is not surprising that so many households were able to accumulate and use savings

to construct an initial structure. The continued dominance of savings is more surprising, given that

government policies reduced the level of subsidies and tightened their application and construction

costs rose sharply. What seems to have taken place is that households interpret &savings' very

broadly, and increasingly rental income emerges as one of the most important components.

Owners in Gaborone are increasingly reliant upon income from rent to consolidate housing, so

that in a sense their housing success is dependent upon the blocked tenure trajectory of others. At

the same time, the assumption that prospective or new owners are able to draw upon savings may

be misplaced as less stable employment markets, in#ation, and changing land and housing markets

make the accumulation of savings increasingly di$cult.

5. Residential mobility, land and 5nance

The early literature on self-help housing identi"ed intra-urban migration as part of a sequence of

events that brought households from rural areas, to inner-city rental housing, and eventually to

&ownership' at the periphery (van Lindert, 1992).`" There, it seemed, these households would stay.

The self-help process itself seemed to provide a strong disincentive to move as house consolidation

could take many years and service acquisition considerably longer.`` While the emphasis on

housing ignored quite high mobility levels in recently established settlements, (especially those

formed by invasion, where households cashed-in on the value of land or left due to violence, see

Gough, 1998; Kellet, 1992), once settlements consolidated residential mobility was con"rmed as

low and vacancy chains short (Gilbert, 1993, 1999; Gilbert & Crankshaw, 1999; Strassmann, 1991;

Tipple et al., 1997). Neither increased occupational mobility nor the supply of new houses onto the

market appeared to generate much residential movement (Baer, 1991; Ferchiou, 1982; van Lindert,

1992). While in Latin America at least, a walk around any low-income settlement reveals numerous

small signs advertising a house for sale, Gough (1998) reports a low rate of success among

households that try to sell. Not only does it appear that mobility is low over the life cycle, but there

is no evidence that it has changed during the economic crisis when the search for jobs, and the need

to reduce housing expenditures and transport costs has been at a premium.

K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357 347

`" Research is required on what is happening to settlements of older self-help and public housing. Despite concerns

about down raiding (upward "ltering) there is ample anecdotal evidence of maintenance problems and deterioration of

public housing projects, and the rising incomes and social mobility of the 1960s seem unlikely to be as widespread today.

In many self-help settlements there appear to be problems of inheritance and rising maintenance costs as resident

incomes fall with old age.

One particular, and under researched, aspect to the self-help process that may have a signi"cant

impact upon mobility levels is the notion of family patrimony. The physical, economic and social

struggle associated with the acquisition of land and the construction of a house, including the

deferred consumption and extra jobs that made its "nancing possible, defence against the police,

the loss of children to "res or illness, and other hardships during consolidation, motivates a strong

sense of attachment. In Mexico, interviewees often described in detail how they had &su!ered' to

acquire a plot and were not minded to move even when faced with short-term "nancial problems:

one respondent claimed he would leave &ma& s que con los pies por adelante' (literally, feet "rst).

Indeed, there was a desire &to leave something for ones children' which might serve as an important

motivation to the allocation of space to kin during the lifetime of the original occupier. But, either

holding patrimony for kin or attempting to sell up are hazardous where inheritance procedures are

cumbersome and both property and family law discriminate against women or certain types of

union (Varley, 2001).

For those that view residential mobility as a key indicator of e$cient housing and land markets

such stasis has been the cause for concern (Malpezzi, 1990; Strassmann, 1991; World Bank, 1993b).

Empirical studies appear to show that mobility is related to the level of government intervention in

housing markets, with stronger intervention and a lack of (access to) "nance having the e!ect of

reducing mobility (Malpezzi, 1990; Strassmann, 1991). Countries with well-developed "nancial

systems exhibit higher levels of residential mobility, although this is also linked to GDP generally

and value-income ratios speci"cally. A lack of "nance means that consolidated houses are more

accessible to better-o! households who have greater access to "nance, rather than to those that

earn less than the seller. Houses that should "lter down may instead "lter up thereby depriving

lower income households of an important source of housing supply (Baer, 1991).`" If housing is to

serve as an asset in poverty alleviation strategies we need to think about what kind of housing

"nance instruments will make housing markets more dynamic without also making them more

exclusionary to the poor.

These aforementioned views are based on studies of mostly macro-data sets and most authors

acknowledge the lack of city-speci"c and household level analysis. Certainly, there are method-

ological problems that need greater attention. The general relationship between mobility and

market distortion, for example, is based largely on normative indices of government intervention.

Yet, if developers and households respond to regulations by segmenting the market into formal and

informal/illegal sectors, with direct government intervention limited in the latter it is unclear

whether the relationship can be sustained (Jones, 1996). Moreover, the &solution' to the problems of

poor households' inability to mobilise capital sunk into housing and their lack of residential

mobility is often regarded as the same. A range of authors and agencies advocate legalisa-

tion/formalisation of tenure as a means to secure property rights and thereby provide access to

a transparent process of property transfer and increase the opportunities for "nance (Dowall

348 K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

`` We acknowledge di$culties with these data. Many respondents were reluctant to &inform' upon neighbours

although 96% answered the question. Despite discussing the de"nition, the concept was problematic with some

respondents using the term to include people living some streets away.

`` Land prices may be important to residential mobility. Between the two cities, the percentage of respondents to

report the movement of a neighbour or a friend was lower in Toluca (12 and 9%) than in QuereH taro (29 and 20%) which

may re#ect the higher land and house prices in Toluca. This, in turn, may mean that the original purchase takes longer

and trading-up is more di$cult.

`" While the response rate su!ered from an informant-e!ect the low level of information casts some scepticism upon

claims of active social networks in low-income settlements. A substantial number of households claimed never to have

spoken to their neighbours and many did not know their names.

& Clark, 1996; de Soto, 2000; World Bank, 1993a). But, the practice of legalisation may also

contribute to households either wanting or having to stay in situ. Many programmes have taken 20

years to complete during which time disputes between settlements and plot holders sometimes

result in litigation, and the interim and "nal legal documents frequently contain mistakes (Jones

& Varley, forthcoming).

Using data from Mexico, we are able to examine whether the second-hand land and housing

markets is static and the potential impact of "nance upon residential mobility. The survey of

low-income settlements in QuereH taro and Toluca found that prior to acquiring the present plot,

only 21% of households had looked elsewhere and only six households had looked for a plot in

more than two settlements. Potential residential mobility was also extremely low. Asked whether

they had contemplated moving from the settlement, 10% of respondents said they had but only 4%

could give precise information on where they had looked and if they had enquired after plot prices.

Respondents were also asked whether direct neighbours had moved in the past 3 years.`` In 78%of

cases no neighbour had departed, in 19% only one neighbour had left, 2% had two neighbours

leave and only two respondents (less than 1%) claimed a turnover of three or more neighbours. The

answer to a similar question about the movement of friends or godparents (compadres) elsewhere in

the settlement provoked a similar response. In 85% of cases no friend had left the settlement, 13%

reported that one close friend had left and only 2% that two or more friends had moved.``

The study attempted to follow up on those households that had moved. Were they unusual, and

was access to "nance a contributory factor to their movement? As the questionnaire had asked for

movers only in the past 3 years we were relatively con"dent that these households would not have

moved from the subsequent residence. Acquiring precise data on household movements, however,

proved di$cult. In the case of neighbours, most respondents were unable to provide a full name but

preferred giving a nickname or abbreviation. Fewer still were able to give a precise location of the

newaddress but o!ered general reference points such as &they moved toward the bus depot'. In such

cases, introductions were made to other neighbours who knew the household better or to a relative

living in the settlement who could "ll in the details or make contact. Needless to say, the drop

out rate was very high: from relatively precise details of 40 households it was possible to locate

just 18.`"

The follow-up survey found that the principal reason for moving was either to improve housing

conditions, to be near relatives or closer to work. In conversation, however, it became clear that

there were a range of less clear-cut reasons for a move, particularly among women. Many

low-income settlements in QuereH taro are on steep ground that makes construction, the installation

K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357 349

"" The high number of vacant plots in settlements even 10 years after formation supports the mobility-service link. In

Penuelas and Nueva Oxtotitlan where water and drainage had only recently and not completely been introduced,

respondents mentioned the rapid increase of plot in-"ll and we interviewed households living in temporary housing who

had decided now to occupy a plot bought many years earlier.

of services and general communication di$cult. In two of the settlements the dirt roads were so

steep that in place of street paving the government and community had installed steps. The women

claimed that negotiating the streets or the steps with shopping, with children and/or when

pregnant, and especially at night, was particularly hazardous. To make matters worse, the steps in

one settlement and the entire area of another was frequented by gangs, again mostly at night, who

would break the few street lights and shower rocks onto the roofs of houses. Although rarely armed

there had been confrontations with the police and shots had been "red in local territorial disputes.

The interviews show that whereas the low price of plots was cited as the most frequent reason for

residing in the original settlement, and many of those that had thought of moving mentioned the

cost of maintaining payments and service installation, the follow-up interviews with actual movers

found that most moved long after payments were completed and none mentioned cost as a motive.

In comparison to the previous settlement, almost all households had improved their housing

situation. Before the move 53% of households possessed housing with only one bedroom but after

the move the "gure fell to 20%. Yet, on average the total size of the new property was smaller and

had less open space. However, the data are skewed as many households had acquired a &social

interest' house so that they had moved from being purchasers of land and builders of housing to, in

some cases, the purchasers of housing. Almost all households also improved the level of service

provision: before the move only 31% of households had drainage, whereas after the move this rose

to 94%.""

These data suggest that if formal or informal "nance were to become more widely available to

low-income households most would not attempt to move but improve conditions in situ. If no such

"nance is forthcoming and housing, service or "nance opportunities arise elsewhere, a signi"cant

number of households will leave. It seems likely that the movers are likely to be better o! than

those that remain behind * social interest housing in Mexico is not low-income housing * and

movers seem not to retain links back to their original settlement. Their departure may have an

adverse e!ect upon the ability of the original settlement to consolidate its service provision and

build social capital.

6. Broadening the agenda

From our reading across the literature and "eld experience in Botswana, Mexico and elsewhere,

it seems clear that research and policy needs to widen its focus away from the &housing' market,

a concern for ownership, and "nance as synonymous with lending, to consider the urban develop-

ment process more broadly. Our discussion above has illustrated how restricted access to "nance

for land acquisition may a!ect the transition from non-ownership to ownership forms of tenure

and/or the time-lag between the acquisition of a plot and the construction of housing. A slow rate

of housing consolidation may be the result of di$culties in assembling "nance for land acquisition

350 K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357

some years earlier. Moving beyond the relationship between land and housing markets, the links

between di!erent sectors of the housing market (viz rental, owner-occupied, sharing) also have to

be recognised. The letting of rooms can hasten the consolidation process by facilitating the

production of housing "nance which in turn may lead to an increase in the supply of rented

dwellings.

A broader perspective on &housing "nance' and urban development should also extend to how

low-income households use housing "nance and how housing "nance schemes (both formal and

informal) are incorporated into their housing and income strategies. It seems clear from research in

Botswana and Mexico that irrespective of whether low-income households are purchasing land,

paying rent or consolidating their homes, they exhibit debt-aversion behaviour and minimise any

in-debt period. This suggests that not only should the sources of housing "nance be as diversi"ed as

possible but that they should take into account established patterns of credit use: namely the need

for short-term, small loans and a reluctance to put assets at risk. Although experience shows that

formal sector "nance institutions, both public and private, are reluctant or unable to adapt their

"nancial instruments to these conditions, little research has been conducted to discover why they

ignore what is potentially their largest market. Researchers have pointed to high transaction costs

of small-scale lending and di$culties of collateral where tenure is extralegal, conditions which

policymakers and researchers seem to consider as "xed and insurmountable. In fact, private

banking in a number of countries has shown considerable innovation in the past decade (Siembieda

& LoH pez-Moreno, 1999; Paulson & McAndrews, 1998) and lending for housing does not need to be

restricted to lending on housing (Datta & Jones, forthcoming).

These lessons already form a part of micro"nance projects in a number of countries and have

mostly been con"ned to micro-enterprise and consumption smoothing initiatives (Johnson & Ro-

galy, 1997). A number of NGOs have adapted the principles of micro"nance or evolved out of their

experience to establish group-based microcredit programmes explicitly designed for housing

(Anzorena et al., 1998; Ferguson, 1999; Mitlin, 1997a; Patel, 1999). These programmes appear

promising in themselves but need more systematic, independent and comparative review of both

strengths and weaknesses (Datta & Jones, forthcoming; Vakil, 1996). A number of issues need

further research. First, NGO micro"nance programmes have tended to concentrate upon housing

and extend into areas of service provision. In many programmes participants already possess a plot

of land or intend to do so in the near future. Our "ndings suggest that the NGO programmes need

to consider more closely the conditions of the land market and whether this is contributing to the

housing "nance problem encountered by participants. Second, some programmes operate short-

term cycles of saving/borrowing as an indication of #exibility but may lock participants into

numerous consecutive cycles (as an indicator of sustainability). Our "ndings suggest that low-income

households need short-term"nance arrangements but not all the time or even often. For reasons that

are unclear households seem to need a break from housing "nance (through savings or credit).

Third, and a "nding that has resonance beyond the work of NGO micro"nance programmes, we

need to know much more about the role of savings. Debt-aversion behaviour is critically linked to

the availability and use of savings which has been a constant undercurrent in our paper. While it is

true that our respondents interpreted savings in a very wide sense, blurred the distinction between

savings and informal "nance, and used the former as a euphemism for a host of domestic resources,

savings performed a vital role in the acquisition of land, housing and the payment of rents. As our

data are retrospective, in the sense that they captured owners who purchased land or consolidated

K. Datta, G.A. Jones / Habitat International 25 (2001) 333}357 351

" Jones and Mitlin (1999) show that NGO}government partnerships can provide scale as well as support for

community capacity building, but questionmarks remain over the "nancial and political sustainability of these pro-

grammes.

houses over a 20-year period, it is dangerous to assume that prospective or new homeowners today

will be able to continue to accumulate savings. It remains imperative, however, that households

gain access to more secure means of saving. Some attempts have been made to encourage saving

through NGO backed micro"nance programmes (Johnson & Rogaly, 1997). But some pro-

grammes use a &savings record' as an indicator of "nancial prudence to allow participants access to

credit within a few weeks of an initial deposit and at high gearing levels (Datta & Jones, 2001).

Rather than regard savings as a means to the end of microcredit, which imposes constraints on the

programme to achieve scale without government subsidies, a savings-only route might be more