Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sandeep (M5 55)

Uploaded by

Sandeep ArikilaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sandeep (M5 55)

Uploaded by

Sandeep ArikilaCopyright:

Available Formats

ASSIGNMENT OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

SUBMITTED BY: - ARIKILA SANDEEP(M5-55)

SALOMON VS SALOMON CASE Facts: The facts of this case were that the owner of a business sold it to a company he had formed, in return for fully paid-up shares to himself and members of his family, and secured debentures. When the company went into liquidation, the owner, because of the ownership of the debentures, won his claim to be paid off in priority to other creditors, as the secured debt ranked at a higher priority to those debts and successfully proved that he did not have to indemnify the company in respect of its debts, as it had a separate legal personality. 1. Mr. Aron Salomon was a leather boot and shoe manufacturer. His firm was in White chapel High Street, with warehouses and a large establishment. He had it for 30 years and "he might fairly have counted upon retiring with at least 10,000 in his pocket." His sons wanted to become business partners, so he turned the business into a limited company. His wife and five eldest children became subscribers and two eldest sons also directors. Mr. Salomon took 20,001 of the company's 20,007 shares. The price fixed by the contract for the sale of the business to the company was 39,000. 2. According to the court, this was "extravagant" and not "anything that can be called a business like or reasonable estimate of value." Transfer of the business took place on June 1, 1892. The purchase money for the business was paid, totaling 20,000, to Mr. Salomon. 10,000 was paid in debentures to Mr. Salomon as well (i.e. Salomon gave the company a loan, secured by a charge over the assets of the company). The balance paid went to extinguish the business's debts (1000 of which was cash to Salomon). 3. Soon after Mr. Salomon incorporated his business, however, a series of strikes in the shoe industry led the government,

Salomon's main customer, to split its contracts among more firms (the government wanted to diversify its supply base to avoid the risk of its few suppliers being crippled by strikes). His warehouse was full of unsold stock. He and his wife lent the company money. He cancelled his debentures. But the company needed more money, and they sought 5000 from a Mr. Edmund Broderip. He assigned Broderip his debenture, the loan with 10% interest and secured by a floating charge. But Salomon's business still failed, and he could not keep up with the interest payments. In October 1893 Mr. Broderip sued to enforce his security. The company was put into liquidation. Broderip was repaid his 5000, and then the debenture was reassigned to Salomon, who retained the floating charge over the company. 4. The company's liquidator met Broderip's claim with a counter claim, joining Salomon as a defendant, which the debentures were invalid for being issued as fraud. The liquidator claimed all the money back that was transferred when the company was started: rescission of the agreement for the business transfer itself, cancellation of the debentures and repayment of the balance of the purchase money.

Principle: Corporate Legal Entity (Separate Legal Entity). 1. A separate legal entity refers to a legal entity with accountability. 2. SLE legally separate business from individual or owner like limited liability Company or a corporation.

Corporate Governance rules recognized in the case: The House of Lords affirmed this principle, and stated that the company was also not to be regarded as an agent of the owner, as the company is at law a different person altogether from the subscribers to the memorandum and the company is not in law the agent of the subscribers or a trustee for them. There are occasions when it seems that the Salomon principle may be unfair, and then the courts are under pressure to review the principle and make decisions contrary to it upon various grounds. This is termed as piercing the corporate veil . Instances where the Salomon principle has been set aside by statute include section 30(3) of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954, which states that where a landlord has a controlling interest in a company, the business of the company can be treated as a business carried on by the landlord, instead of two separate legal entities. Also section 24 of the Companies Act 1985, as amended by Companies (Single Member Private Limited Companies) Regulations 1992 states that where a public or unlimited company s membership falls below the prescribed minimum, being two members for more than six months, any person being the sole remaining member is jointly and severally liable for the debts of the company, which takes away the separate legal identity. Judgment: 1. The House of Lords did not find any form of fraud or deliberate abuse of the corporate form; on the contrary Salomon was a victim in that he did his best to rescue his company by

cancelling the debenture he took and raising them to an outside creditor who provided fresh loan capital. 2. This honesty and good faith on the part of Salomon prevented him from indemnifying the company creditors. The House of Lords found there is a legal entity properly formed and there was no use of lifting the veil between Salomon and his company. The business belonged to the company and not to Mr. Salomon. 3. As a result of the Court of Appeal refusal to recognize the existence of the legal entity and regarding the company instead as a myth and fiction, they thought that the business belonged to Aron Salomon.

ENRON CASE Facts:The Enron-private action was characterized by Judge Harmon, the presiding judge, as probably the largest and most complex [litigation] of its kind in the history of this country. This case focuses on the international market environment and political behavior particularly, the dynamic and conflictual coexistence of Corporations and States within national regulation of the impacts of Multinational Enterprises (MNEs). The Enron scandal, revealed in October 2001, eventually led to the bankruptcy of the Enron Corporation, an American energy company based in Houston, Texas, and the dissolution of Arthur Andersen, which was one of the five largest audit and accountancy partnerships in the world. In addition to being the largest bankruptcy reorganization in American history at that time, Enron was attributed as the biggest audit failure. The Enron failure demonstrated a failure of corporate governance, in which internal control mechanisms were short-circuited by conflicts of interest that enriched certain managers at the expense of the shareholders. Although derivatives made appearances in the course of the governance failures, they played no essential role. Enron s actions appear to have been undertaken to mislead the market by creating the appearance of greater creditworthiness and financial stability than was in fact the case. The market in the end exercised the ultimate sanction over the firm.

Even after Enron failed, the market for swaps and other derivatives worked as expected and experienced no apparent disruption. There is no evidence that the market failed to function in the Enron episode. On the contrary, the market did exactly what it is supposed to do, which is to use reputation as a means of monitoring market participants There is no evidence that existing regulation is inadequate to solve the problems that did occur. Had Enron complied with existing market practices, not to mention existing accounting and disclosure requirements, it could not have built the house of cards that eventually led to its downfall. Shareholders lost nearly $11 billion when Enron's stock price, which hit a high of US$90 per share in mid-2000, plummeted to less than $1 by the end of November 2001. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) began an investigation, and rival Houston competitor Dynegy offered to purchase the company at a fire sale price. The deal fell through, and on December 2, 2001, Enron filed for bankruptcy under Chapter 11 of the United States Bankruptcy Code. Enron's $63.4 billion in assets made it the largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history until WorldCom's bankruptcy the following year.

WORLDCOM CASE Q1-What are the advantages and disadvantages of aggressive merger policy like that of WorldCom? Ans- The advantages of the aggressive merger policy that WorldCom had were the following: 2. Through this aggressive merger policy WorldCom Covered a huge amount of market share and it was able to efficiently control the entire market. 3. As the company was able to cover a huge part of the market share it was able to follow a monopolistic approach.

4. WorldCom was able to create value for its stakeholders and shareholders thereby creating value for the firm. 5. It was able to integrate various companies association and leverage their benefits. 6. WorldCom was able to share large houses of Databases, and could serve the point of customer satisfaction as a whole. 7. WorldCom was able to sit upon and prosper with a large amount of assets. 8. WorldCom was an obscure long distance telephone company but through the execution of an aggressive acquisition strategy they evolved into the second-largest long distance telephone company in the United States and one of the largest companies handling worldwide Internet data traffic.

9. WorldCom provided mission-critical communication services for tens of thousands of businesses around the world. 10. WorldCom was able to carry more international voice traffic than any other company. 11. It also carried a significant amount of the world's Internet traffic. 12. WorldCom owned and operated a global IP (Internet Protocol) backbone that provided connectivity in more than 2,600 cities and in more than 100 countries. 13. It owned and operated 75 data centers on five continents.

The disadvantages of the aggressive merger policy that WorldCom had were the following: 1. A huge team is required to control all the companies, to supervise all the activities of the company, which is a real tough and requires a large amount of resources. 2. This is a time-consuming process that involves thoughtful planning and considerable senior managerial attention. 3. Several legal procedures are to be accomplished regarding this type of aggressive acquisition. 4. Financial integration must be accomplished through GAAP principle which is also a lengthy process.

Q2-What motivations could explain the fraudulent account of WorldCom?

Answer: Through fraudulent reporting, WorldCom maintained an Expense to Revenue (E/R) ratio at a level of 42%, when in reality it was above 50%. This Key Performance Indicator (KPI) directly affected the share price. It was essential for Bernie Ebbers (CEO) that WorldCom s share price did not fall, as his stock financed his personal businesses. When performance of WorldCom failed to improve, two fraudulent accounting methods were employed: y Improper line cost adjustments y Revenue manipulation. Line Costs: WorldCom s largest expense was line costs; costs of carrying a voice call or data transmission from its starting point to its ending point. Line costs were improperly adjusted in two ways. Firstly, the release of accruals was made at the request of Scott Sullivan (CFO) to the value of $3.3billion.In 1999-2000 WorldCom, accruals for line costs were released having no matching reduction in estimated costs. The second improper adjustment of line costs was the capitalization of such expenses on the balance sheet. Sullivan reasoned that line costs could be recognized as capital expenditure, and therefore as an asset on the balance sheet under the heading pre-paid capacity , rather than as an operating expense on the income statement. Under US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), operational costs must be reported as an expense in the income statement but it was not done eventually. The consequence was a reduction in reported expenses. Improper Revenue Manipulation: The second fraudulent method was the notion that WorldCom s consistent double-digit revenue growth led to high performance of the WorldCom stock. Continued revenue growth was a strategy instilled by Ebbers that was In every brick of every building . When WorldCom failed to meet his

expectations, accounting entries were made in a process named close the gap . WorldCom inflated revenues by taking money from reserve accounts, initially set up to pay for potential losses from specific predictable events. They then showed it as revenue from operations. This process was against accounting policies specified under US GAAP. This enabled the company to add $2.8billion to the revenue line. This manipulation again helped maintain the E/R ratio at 42%. Q3-What are the facts of this case? Ans- The facts are as follows: 1. With the additional $65 million loan, Ebbers agrees stocks as collateral for the total of $408 million company loan. 2. Ebbers resign as CEO and Sidgmore is appointed as the successor. 3. Internal auditor Gene Morse discovers an asset of $500 million in fraudulent computer expenses. 4. Jack Grubman underperform . downgrades WorldCom stocks to

5. Stocks falls 20% in after hours trading, Myers resigns, Sullivan is fired and 17,000 employees are made redundant. 6. Ebbers, Sullivan, Grubman and Anderson are under investigation. 25 banks file lawsuit and request $2.65 billion on WorldCom assets. 7. WorldCom files the largest bankruptcy in the world.

8. Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002 is signed into law. 9. An additional $3.3 billion in accounting fraud totaling $7.68 billion. 10. Sidgmore resigns as CEO while Myers pleads guilty and testifies against Ebbers. 11. Buford Yates, Betty Vinson and Troy Normand plead guilty to charges of conspiracy and fraud.

12. WorldCom s collapse was the largest corporate bankruptcy of all time, an undesirable title it retained until September 2008, when the collapse of Lehman Brothers triggered the recent banking crisis. WorldCom s collapse caused collateral damage to other telecommunications firms, government, workers, and the capital markets.

ASHBURY RAILWAY CARRIAGE CASE Facts: 1. The company was incorporated under the Companies Act 1862 and had as its objects the following: "The object for which the company is established are to make and sell, or lend on hire, railway-carriages and wagons, and all kinds of railway plant, fittings, machinery, and rolling stock; to carry on the business of mechanical engineers and general contractors; to purchase and sell, as merchants, timber, coal, metals, or other materials; and to buy and sell any such materials on commission, or as agents."

2. It entered into a contract to finance the building of a railway in Belgium by Riche but later wanted to get out of the contract. It consequently argued that it was UV. In the courts below, much had turned on whether or not the transaction had been ratified because the company had an old deed of settlement clause in its articles which provided for extension of the objects by special resolution.

Principle: The Doctrine of Ultra Vires: The expression ultra vires consists of two words: ultra and vires . Ultra means beyond and Vires means powers. Thus the expression ultra vires means an act beyond the powers. Here the expression ultra vires is used to indicate an act of the company which is beyond the powers conferred on the company by the objects clause of its memorandum.

An ultra vires act is void and cannot be ratified even if all the directors wish to ratify it. Sometimes the expression ultra vires is used to describe the situation when the directors of a company have exceeded the powers delegated to them. Where a company exceeds its power as conferred on it by the objects clause of its memorandum, it is not bound by it because it lacks legal capacity to incur responsibility for the action, but when the directors of a company have exceeded the powers delegated to them. This use must be avoided for it is apt to cause confusion between two entirely distinct legal principles. Consequently, here we restrict the meaning of ultra vires objects clause of the company s memorandum.

Corporate Governance rules recognized in the case: The doctrine of ultra vires could not be established firmly until 1875 when the following case was decided by the House of Lords. The reason appears to be this that doctrine was not felt necessary to protect the investors and creditors. The companies prior to 1855 were usually in the nature of an enlarged partnership and they were governed by the rules of partnership. Under the law of partnership the fundamental changes in the business of partnership cannot be made without the consent of all of the partners and also the act of one partner cannot be binding on the other partners if the act is found outside his actual or apparent authority, but it can always be ratified by all the partners. These rules of partnership were considered sufficient to protect the investors. On account of the unlimited liability of the members, the creditors also felt themselves protected and did not require any other device for their protection. Besides, during early days the doctrine had no philosophical support. The doctrine is based on the view that a company after incorporation is conferred on legal personality only for the purpose

of the particular objects stated in the objects clause of its memorandum. The decision in this case confirmed the application of this doctrine to the companies by registration under Companies Act.

Judgment: The House of Lords held unanimously that the contract was beyond the objects as defined in the objects clause of its memorandum and, therefore it was void, and the company had no capacity to ratify the contract. The company had only such objects as were specified in its object clause. Benjamin QC had argued the ratification point but the HOL rejected this argument on the basis that the act was void and it was not possible to ratify a void act. Decision: The House of Lords held that an ultra vires act or contract is void in its inception and it is void because the company had not the capacity to make it and since the company lacks the capacity to make such contract, how it can have capacity to ratify it. If the shareholders are permitted to ratify an ultra vires act or contract, it will be nothing but permitting them to do the very thing which, by the Act of Parliament, they are prohibited from doing.

You might also like

- Rem 6Document42 pagesRem 6Sandeep ArikilaNo ratings yet

- Rem 5Document17 pagesRem 5Sandeep ArikilaNo ratings yet

- Jack Welch The Great Corporate CommunicatorDocument7 pagesJack Welch The Great Corporate CommunicatorDeepak KumarNo ratings yet

- Pravin Pandey (m5-25)Document18 pagesPravin Pandey (m5-25)Sandeep ArikilaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- CibcDocument131 pagesCibcianfeng202211No ratings yet

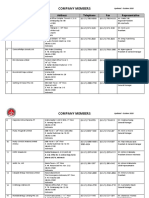

- Company Members: No. Company Address Telephone Fax RepresentativeDocument5 pagesCompany Members: No. Company Address Telephone Fax RepresentativeBFJ TreasNo ratings yet

- List of Scheduled Commercial Banks: (Refer To para 2 (B) of Notification Dated April 13, 2020)Document2 pagesList of Scheduled Commercial Banks: (Refer To para 2 (B) of Notification Dated April 13, 2020)Pankaj GaurNo ratings yet

- Pcab LlimDocument634 pagesPcab LlimPankaj RaneNo ratings yet

- CH 15Document8 pagesCH 15Saleh RaoufNo ratings yet

- Agency and Business Organization DutiesDocument5 pagesAgency and Business Organization DutiesSam Hughes100% (1)

- Cross-Border InsolvencyDocument3 pagesCross-Border InsolvencySameeksha KashyapNo ratings yet

- Business Models For Ethanol ProductionDocument47 pagesBusiness Models For Ethanol Productionres06suc100% (1)

- Pioneer Insurance V CADocument1 pagePioneer Insurance V CAKim LaguardiaNo ratings yet

- CompanyDocument49 pagesCompanybabi 2No ratings yet

- CBLDocument3 pagesCBLmuhammadsudrajadNo ratings yet

- Starwood Hot 2008 Annual ReportDocument178 pagesStarwood Hot 2008 Annual ReportEijaz AnwarNo ratings yet

- Maxima Holdings plc Reports Strong Growth and ProfitsDocument42 pagesMaxima Holdings plc Reports Strong Growth and ProfitsEmily Bre MNo ratings yet

- Fria List of CasesDocument2 pagesFria List of CasesJhomel Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- E&Y ContactsDocument2 pagesE&Y ContactsZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- List Aii BCCDocument5 pagesList Aii BCCYatsen Jepthe Maldonado SotoNo ratings yet

- Orgman W4 PDFDocument6 pagesOrgman W4 PDFCent BNo ratings yet

- Malaysia Company LawDocument30 pagesMalaysia Company LawTan Cheng Ying100% (4)

- Case CountsDocument14 pagesCase CountsChaitali DegavkarNo ratings yet

- May 2020 - AP Drill 1 (SHE & Liabs) - Answer KeyDocument10 pagesMay 2020 - AP Drill 1 (SHE & Liabs) - Answer KeyROMAR A. PIGANo ratings yet

- 08 - Table of CasesDocument15 pages08 - Table of CasesSunny PardeshiNo ratings yet

- QUIZDocument5 pagesQUIZNastya MedlyarskayaNo ratings yet

- Business Organizations OutlineDocument33 pagesBusiness Organizations OutlineMichelle1717100% (2)

- Placement PapersDocument18 pagesPlacement Papersramya173No ratings yet

- The Goals and Functions of Financial Management: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument29 pagesThe Goals and Functions of Financial Management: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinJamil AhmedNo ratings yet

- Ep Os Module 1 Dec 20Document93 pagesEp Os Module 1 Dec 20Monika SinghNo ratings yet

- Grab Taxi - Navigating New FrontiersDocument4 pagesGrab Taxi - Navigating New FrontiersZhenMingNo ratings yet

- Bank of CyprusDocument7 pagesBank of CyprusLoizos LoizouNo ratings yet

- Pengumpulan Maklumat Speedtest Dan Telco Di KK September 2023Document81 pagesPengumpulan Maklumat Speedtest Dan Telco Di KK September 2023aonemosNo ratings yet

- Sol. Man. - Chapter 10 She 1Document9 pagesSol. Man. - Chapter 10 She 1Miguel AmihanNo ratings yet