Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Natalia 28 (1998) Complete

Uploaded by

Peter CroeserOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Natalia 28 (1998) Complete

Uploaded by

Peter CroeserCopyright:

Available Formats

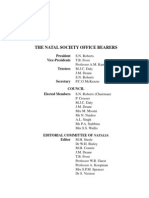

THE NATAL SOCIETY OFFICE BEARERS 1998 -1999

President

Vice-Presidents

Trustees

Treasurers

Auditors

Director

Assistant Director and

Secretary to the Council

S.N. Roberts

Dr F.e. Friedlander

TB. Frost

M.1.e. Daly

A.B. Burnett

S.N. Roberts

KPMG

Messrs Thornton-Dibb,

Van der Leeuw and Partners

Mrs S.S. Wallis

1. C. Morrison

COUNCIL

Elected Members S.N. Roberts (Chainnan)

Professor A. Kaniki (Vice Chairman)

Professor A.M. Barrett

A.B. Burnett

1.H. Conyngham

MJ.e. Daly

lM. Deane

TB. Frost

Professor W.R. Guest

e. Manson

Mrs T .E. Radebe

A.L. Singh

Ms P.A. Stabbins

Transitional Local Council Professor C.O. Gardner

Representatives E.O. Msimang

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE OF NATALIA

Editor

Associate Editor

Secretary

lM. Deane

TB. Frost

Dr W.H. Bizley

M.H. Comrie

Professor W.R. Guest

Dr D. Herbert

F.E. Prins

Mrs S.P.M. Spencer

Dr S. Vietzen

G.D.A. Whitelaw

DJ. Buckley

Natalia 28 (1998) Copyright Natal Society Foundation 2010

Natalia

Journal ofthe Natal Society

No. 28 December 1998

Published by Natal Society Library

P.O.Box 415, Pietermaritzburg 3200, South Africa

SA ISSN 0085-3674

Cover Picture

Briar GhylL Pietermaritzburg, c. 1884.

showing original (c. 1868) detached kitchen to rear of house.

(Drav.-ing by Dennis Radford, author of the article on p.34 of this issue.)

7'Jpeset by A1.J. Marwick

Printed by The Natal Witness Printing and Publishing Company (p(v) Lld

Contents

Page

EDITORIAL................................................ 5

REPRINT

.I travelled to other worlds'

R. Papini .......... ........................ ....... ... ............................... (,

ARTICLES

Exotic yet often colourless

1 ~ 1 H : v n Jenkins ... :............................................................... 14

Toponymic lapses in Zulu place names

Phyllis J.l'./. Zungu ...... ... .......... .......... ............... .............. ... 23

The pioneer Natal settler house

Dennis Radford ... ... ..... ........ ..... .............. .... ..... ............. .... 34

Barracks and hostels

Robert Honze ... ... ..... ..... ... ... ..... ..... ....... ............. ........... ...... 45

An environmental manifesto for the greater

Pietermaritzburg area

Dai Herbert and GmJin White/aw .. ............... ........... .......... 53

OBITUARIES

John Mowbray Didcott ...................................................... 64

Keith Oxlee ....................................................................... 66

Ronald George MacMillan ................................................ 69

Christopher Cresswell ....................................................... 70

Derrick John .Jackie' McGlew .......................................... 72

Owen Pieter Faure Horwood .............................................. 74

NOTES AND QUERIES.................................... 75

BOOK REVIEWS .................................... 85

SELECT LIST OF RECENT

KWAZULU-NATAL PUBLICATIONS 94

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

C

O

N

S

E

R

V

I

N

G

T

H

E

B

U

I

L

T

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

.

(

s

e

e

p

.

5

3

)

M

a

n

y

m

e

e

t

i

n

g

s

o

f

t

h

e

g

r

o

u

p

t

h

a

t

p

r

o

d

u

c

e

d

t

h

e

E

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

a

l

M

a

n

i

f

e

s

t

o

f

o

r

P

i

e

t

e

r

m

a

r

i

t

z

b

u

r

g

w

e

r

e

h

e

l

d

i

n

t

h

i

s

b

u

i

l

d

i

n

g

,

t

h

e

T

e

m

b

a

l

e

t

u

C

o

m

m

u

n

i

t

y

E

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

C

e

n

t

r

e

.

A

d

e

r

e

l

i

c

t

f

o

r

m

e

r

g

i

r

l

s

'

b

o

a

r

d

i

n

g

s

c

h

o

o

l

,

i

t

w

a

s

r

e

s

t

o

r

e

d

a

n

d

r

e

n

o

v

a

t

e

d

i

n

a

p

r

o

j

e

c

t

w

h

i

c

h

t

a

u

g

h

t

b

u

i

l

d

i

n

g

t

r

a

d

e

s

k

i

l

l

s

t

o

m

a

n

y

u

n

e

m

p

l

o

y

e

d

p

e

o

p

l

e

.

(

P

h

o

t

o

g

r

a

p

h

:

D

.

G

.

H

e

r

b

e

r

t

)

Editorial

Of the two pairs of articles in this issue of Natalia, one is fortuitous, the other a

result of editorial planning. The architectural-historical pieces on the early Natal

settler house and on workers' barracks and hostels were submitted by their authors

unbeknown to each other: but wishing to publish something about the place names

of this province, we asked professors Zungu and lenkins to cover Zulu and non-Zulu

place names respectively.

There is an element of uncertainty about the 'Reprint' section. We know that

Carl Faye's paper containing an account of a 'close encounter of the third kind' was

offered to the South African family weekly, the Dutspan, which ceased publication

in 1957: and it appears to have held the copyright. It would, however, have been too

time-consuming and unproductive a task to comb through more than 1 500 un

indexed issues of the magazine to find it. If the Dut.span did in fact print the piece,

then it is truly a 'reprint': if not, then it will prove to have been a 'previously

unpublished piece'! Perhaps its previous publication will be confirmed by someone

with a long memory, an interest the paranormal and a scrapbook.

The fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Alan Paton's Cry, the Beloved

Country could not go unmarked in his birthplace, Pietermaritzburg, or in this

journal. Notes & Queries records the commemorative programme arranged by the

Alan Paton Centre at the University of Natal, some memories of Paton as

schoolmaster, and some other literary connections with the city. One of the books

reviewed is an autobiography set mainly in Pietermaritzburg. All of this ensures that

Clio doesn't monopolise the limelight in this issue.

Yatalia 29, due to appear in December 1999, will appropriately mark the

centenary of the beginning of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902.

The price of Natalia has remained at R25 for a number of years, but from the

next issue it will unfortunately have to be increased to R30, and South African

subscribers will now be required, like overseas subscribers, to pay postage. The

insert order form for the next issue gives details.

1.M. DEANE

'1 travelled to other worlds'

Introduction

In Noyember 1912, ANC founder John Dube. trying to organise resistance to the

Union's impending anti-African legislation. harangued a gathering of Zululand

chiefs at Eshowe for lack of unity in defence of their interests. Among his

imprecations was one against 'ridiculous rumours among you about flying bodies

coming through space' (Faye 1923: 87). This kind of tantalising pointer to evidence

of African sightings of UFOs might well crop up in other official records. but until

the recent American publication of the media-savvy isangoma or isazi (seer)

Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa's Song of the Stars (1996), nothing in the nature of an

account of extraterrestrial contact from a Zulu source has appeared in popular print.

Dube's question to the chiefs immediately following the above 'What do your

doctors say about these things?' reveals his opinion as to which sphere of culture

such matters rightly belong. and indeed considerable claims are made by inyanga

Mutwa of contact. both firsthand and from hearsay. Although the formal

ethnographic record may yield next to nothing in respect of diviners' utterances

regarding the extraterrestrial

l

. one of the earliest indigenous voices - Canon

Callaway's main informant Mpengula Mbanda speaks quite plainly of 'the people

\",ho. we suppose. are on the other side of the heaven' , which was conceived of as a

blue rock encompassing the earth. Vague as he was regarding their location ewe do

not know whether they are on the rock", or whether there is some little place which is

earth on the other side), Mpengula was unequivocal about the reality of abantu

bezulu (people of the sky). 'The one thing we know is this, that these heavenly men

exist. Therefore we say there is a place for them, as this place is for us' (Callaway

1970a: 394). Call away himself in his Nun,'ery Tales says that 'so far as [he]

know[s]. every where among the people of all tribes, [there is] a belief in the

existence of h e a v e n ~ v men' (1 970b: 316, Appendix).

Today this tradition finds lavish - some would say opportunistic - expression in

the latest offering from the reconstructed and nowadays warmly feted Mutwa

2

. His

of the Stars. subtitled Lore of a Zulu Shaman, consists of transcriptions of his

cosmogonic monologues by American admirers. and presents in an eponymous

chapter what might be called an . Afrocentric UFOlogy', in the shape of what he

calls the . mere outline' of a . great story that tells of the extraterrestrial origins of

humankind' (:125). This is just one part ofa heritage of 'amazing knowledge of the

cosmos. the solar system, and even dimensions unknown to man' once possessed by

black South Africa (: 123).

Xatalw 28 (1998). R. Papini pp. 6-13

7

J travelled to other worlds

This body of lore exists, moreover, throughout the continent. When in Kenya

during the Mau Mau uprising, the urbane and well-travelled Mutwa found that an

encounter with a 'gigantic disk' and its bright floating satellite globes left him

considerably more agitated than some traditional Africans hard by in their 'skins

and long robes' (: 140), He details several other encounters (including an incident in

Natal in which a 'hardened policeman' fired on a UFO!), in order to assert that

'black people of all tribes have a long tradition of dealing with things like these

flying things from outside the Earth' (: 141). It is only with reticence. however, that

they disclose what they know: 'You come across a similar runiform! my1hology

though I think they won't tell it to strangers. (: 133).

Notwithstanding this, in perhaps the best-known of South African UFO tales,

Bevond [he Light Barrier. author Elizabeth Klarer

3

implicitly claims that

indigenous knowledge of otherworld civilisations was divulged to her. by induna

'Ladam' (Laduma?) during her girlhood on her family's Drakensberg farm: in

Natal. His 'prophecy' allegedly included the somewhat startling assertion that

Klarer's blonde hair would 'bring the Abelungu (white people) from the sky ...

They are the sky gods who once lived in this world, but afterwards ascended . . .'

(: 19),4 Though its protagonist was spared any such unsettling revelation. the present

account would seem to constitute a like exception to any Africa-wide tradition of

secrecy, It was imparted by an old-world, tribal Zulu, Maphelu Zungu, to a white

woman. Nimba Lulla McAyre. I have been unable to discover who she was, much

less ho\v she came to obtain the account. Nor is it known whether she transcribed it

in Zulu or English. and if the former, whether the translation too is her work, or

that of the man who preserved the text the long-serving Native Affairs

Department interpreter Carl Faye

5

, in whose papers it is one among several oral

histol)' interview transcripts. Nor is there any date on the original typescript or any

ready way of establishing when the encounter took place, or when the account of it

was transcribed

6

.

The flimsy typescript certainly found its place in Faye's collection thanks to his

long-standing relationship with its narrator and protagonist. Maphelu the son of

Mkhosana kaSangqwana Zungu, who was cousin to Ngqumbazi , the concubine of

King Cetshwayo who bore his successor Dinuzulu

7

. 'Maphelu and 1', Faye says,

'knew each other for years'. probably through the agency of Faye's mother-in-law

Mrs Eileen Matthews, a granddaughter of Henry Francis Fynn (1803-61). Maphelu,

whose birth is estimated by Faye as c.1853; died in about 1946. He had been in the

service of Fynn's son, also Henry Francis (1846-1915) when the latter was British

Resident Commissioner with Cetshwayo in Zululand north of the Mhlatuze.

Consequently Maphelu heard much about the elder Fynn, and knew the izibongo of

both mens.

Assuredly it was such connections, as well as his patrician birth, that made

Maphelu Zungu a Native Affairs Department favourite in Zululand and Natal. such

that Faye, when taking down his eyewitness account of Cetshwayo's capture

9

,

prefaced it with an interesting biographical sketch, which is worth quoting at some

length for the graphic impression it gives of the text's narrator:

8

I travelled to other worlds

In appearance Maphelu was a man of medium Zulu build and height, well-knit

and wiry. He was of a restless disposition, had sharp eyes, was quick in

movements, had somewhat thin lips for a Zulu, was inclined to speak rapidly

and be repetitive and was apt to disregard details, but with all that, was openly

friendly. He liked visiting, and would soon be off, slightly leaning forward, his

gait typical of that of a Zulu on an errand. In advancing age he had a staff,

udondolo, and when out walking he would put this across the small of his back,

holding it with both hands crotched backwards. There was always an air of

dignity about Maphelu.

He had fought at Isandlwana and Ulundi, and his 'gory life' included a coup

count of twenty-two of which Faye is 'certain', and the alleged murder of a

missionary, for which he was apparently sentenced to death but subsequently

pardoned. Most importantly for an appreciation of the present text however. Faye

stresses that Zungu had apparently reconciled himself to the fact of conquest:

[He] lived to see the extensive advance made in Zululand by the work of the

whites, through their ever-increasing skills, and he had seen the benefits which

this had brought to the inhabitants. The old warrior had seen that ... the white

man had diligently brought to the Zulus ever so much of the Abalumbi' s

(wonder-workers') knowledge, abilities, helpfulness, healing and soothing

doctoring, money economy, and much else, and had shown the [Zulus] how to

do useful and profitable work for themselves. The white man had as well

brought 'quick machines' for doing work, also swift means of communication,

all wizardry undreamt -of.

It is probably also helpful to mention here, for the benefit of readers sceptical of

the account's authenticity, that a variant typescript of Faye's biographical note says

'the old warrior had noticed that ... the white man had quietly brought to the Zulus

ever so much of the white man's knowledge, abilities, enlightenment "even flying

up into the sky" , (p. 5, my emphasis). Even the title of the piece, such sceptics

might argue, is strictly speaking unfitted to the events it relates, and smacks of little

more than journalistic attention-grabbing. Those familiar with Zulu idiom might be

able to judge whether the narrative rings troe. If it has a contrived feel, they may

choose to t::tke Nimba McAyre for another Elizabeth Klarer, seeking to put on her

personal cosmology the stamp of the singular brand of authentication afforded by a

native voice or witness. Those on the other hand who are content to take the tale in

the millennial spirit, may prefer to believe after all, with Mutwa, that indeed 'if you

scratch below the surface, all our tribal people have stories about the stars' (:121).

9

1 travelled to other worlds

I Travelled to Other Worlds

by a Zulu

Much it is that I have seen in my time, but this ... this is like a dream.

This is what happened. I was on a journey from my home in the lowlands, to

visit people in the highlands a day's walking distance. At last I got to the

mountains, and edged upwards. In one part of the ascent the path is flanked by a

sheer rocky rise, and at the foot of this towering place is flat grassy land, quite wide,

crossed by the path. Below this haugh [sic] or shelf is a steep slope with boulders,

where there are snakes and rock-rabbits, klipspringers and baboons.

There on the shelf I sat down to rest and took out my snuff, and sniff-sniffed

whiff-whiffed. I snuffed and looked around. Then I saw something odd, something I

had never noticed before. It was a very big rock, smooth and egg-shaped, there right

next to the precipice.

I asked myself audibly, 'What is this?'

So I went to look at it, put my hand on it, and it was very slippery in all

directions. like wet clay. but it was quite dry. Then I thought I felt it move, and off I

cleared, lest it roll over me. At a safe distance I stopped, to watch.

The thing kept moving, slowly slowly, up up it moved. Away I ran at top speed,

to the side of the flat ground where the foot-path enters, and there (stopped and)

stood. because if it crashed from so high up it might do a lot of damage and leave

nothing of me but bits and pieces.

As I was running I caught glimpses of my stomach. You see for yourself that it is

a nice stomach, serving me well - it is of good capacity (tapping it). With the haste

of running. the stomach was wabble-wabbling, yibble-yibbling, and I wondered

whether it would ever serve me again for mabele (Zulu beer). Terrible.

There I stood, and asked myself, 'Hau, are you then dreaming?' I looked

upward. but there was nothing at all to see now - the Thing wasn't there gone,

clean gone.

I sat down. I looked at myself. and I was still really myself; I looked around, and

it was just ordinary broad daylight, the sun was shining. I took out my snuff and

tapped some out onto my palm, sniff, whiff, whiff, sneeeff - ah. I said to myself. No,

I will go ahead and make my visit to the people in the highlands.

So I started, meaning that when I had got to the top of the climb I would hasten

onward, where the country was easier. But on getting within full view of the

precipice at the side of the flat shelf, there the Thing was again, as I had first seen

it.

This was scandalous and now I became scared, mature though I be - properly

scared: why should this happen to me, of all people?

A bearded man in his prime now appeared, coming from the Thing, but from

nowhere that I cQ.uld make out, and he walked with a stately gait toward me. It was

a person unknown to me, but at any rate a person, so I waited. My heart told me to

run for it but I refused, for he was unarmed and I had my assegai.

to

I travelled to other vv'orlds'

He came up to me, and before I could greet him, in the usual way, he said

something which sounded like 'wufu-wufu' in his beard. That beat me, and I just

looked at him. Then he undid a small neatly plaited grass satchel from a necklace he

was wearing, and took out a charm. He broke this in two, and put one piece into his

mouth and started chewing. He put the other piece into my mouth. I found myself

chewing too, and it was a bit bitter, but I swallowed. What else could I do?

He spoke again, and -marvel of marvels - I knew his speech language as well as

my own.

The . wufu-wufu , was really Zungu, my very family name. He said Zungu, you

have been scared. but all this will do you no hurt. I have come here in that (pointing

to the Thing). to see something, and my wife is with me, and our two children. All

is good. harmless. I came to this spot because I thought it was secluded, and that

nobody would notice anything. But now you are here, and you see this (again

pointing to the Thing), and I have no choice but to shmv you inside you have

lighted on my secret errand. which can no longer be concealed from you. We are on

a peaceful mission. Let me show you hmv we are travelling. Come and see inside.

\Vith that he walked toward the Thing, and I followed close to him.

Just as we started walking, the lower part of the Thing began to raise itself, as a

bird raises its wings, until it had mushroomed right out but there was no split to be

seen in the spread: the spread was complete, like an open umbrella.

I then saw that this base of the Thing was flat and that it was standing upright

on its flat.

A cleft appeared in the wall, and became a doonvay. He walked in. and I too

walked in. and we were both standing on an even floor.

The part of the floor where we were standing rose very gently, and above our

heads the ceiling opened, and we passed through the ceiling into the upper

apartment and stopped there. We had been lifted. I had felt nothing.

That upper apartment was very nice and cosy. I was gazing around this, when a

doorway opened. and there were the man's wife and two children - a boy and a girl,

the lad old enough to herd goats, and the girl to carry water. They sat down.

The mother busied herself with decorating a calabash milk-vessel, and the girl

put down beads and did'beadworking.

During this time the man had been talking to me. He asked, 'Whither were you

goingT I told him. 'To people on the highland, on my way from the lowland'.

Thereupon he said, 'Seeing you have thus been detained, through you having

noticed this carrier of mine, 1 will lift you up in it and take you to near your

destination. You will be there by sundown. There is no need for you to have any fear

you will feel nothing at all. Merely tell me how long it takes you to walk there, the

direction from here, and what the home you are visiting is like, how many huts, the

stock-fold, and what is to be seen growing there. Do you now', he asked, 'feel

anything?' 'No', I said, 'I feel nothing'. He said, 'You see, you feel nothing, and we

are up in the air. Let me show you'.

With that he went to the side of the apartment, and something parted. He looked

dmvn. and beckoned to me, saying, 'Come and see, and have no fear; this is for

11

! travelled to other worlds

seeing with the eyes only, and cannot make an open hole: it is like a window that is

fixed firmly'.

I went and looked.

How surprised I was! There, below, like a picture. was the country, a big expanse

of it 10'\'land and highland. hills and herding cattle, and the smaller boys herding

goats separately. Some of the bigger boys were playing stabbing the insema bulb [a

traditional boys' game], hurled down a slope, bounding and bouncing like a buck

whilst the competitors, in a row, threw their imitation assegais of sharpened thin

sticks, others with leafy branches. I saw eveI)thing, and recognised homes I knew.

I said I was satisfied, and the view-giver closed.

Turning. I noticed that the man's small daughter was talking to herself as she

was doing her beadwork talking in the speech I knew. I listened.

She picked up a bead. and said, 'My heart is black because of you, and I don't

like you any more'. Then she picked up a red one. and said, 'My heart is now red

like blood, for you have made me cross'. So she was saying as she strung each bead.

The green one: 'Now my heart is quietened, for I see the green grass. and the cattle

are grazing'. A blue one: 'Now my heart is (quietened) glad again, for I see the blue

on a clear day'. A straw-coloured bead: 'Here my heart is pleased, the grass is

yellovving, and we shall reap, and we shall go out and cut thatching grass and make

our homes snug'. A white one: 'Oh, I see only happiness!'.

Then the man spoke to me, saying 'You have been hearing my child as she

strings beads. Now we are above cloud, and you have felt nothing'.

We went to the viewer. and it opened. There below, I saw a wonder: no land,

everywhere white, all crimply, different from what clouds are like from the earth.

Away away up the dome of the sky was the half-moon, still aloft, all by itself there,

as though flung on the sky and just stuck there. The sun was shining, but was

obscured now by cloud. The viewer closed.

The man said, 'Now I shall take you down, to be in good time for your visit'. He

said soon after. 'Come now to the seeing place, and direct me, for we are over the

highland (homes) and homes are clear to the eye. I indicated to him, and we got

near the home I wanted to visit. The viewer closed, and soon he said, 'We are down

on the earth'. I had felt nothing nothing.

He said. 'Come. and stand with me here on the alighting place'. Next we were

on the ground. the two of us.

I had been half a day's foot journey without having waked at all, and here I was

right close to my destination, and I saw people of the home I was visiting - but they

took no notice, as if they did not see us.

The man said, 'Come back, forget not your assegai', and we went back. 'Where

did you leave it?' he asked. I looked, but I saw no assegai. He put out his hand, and

said. 'But here it is', and then I saw it, and he handed it back to me. 'Farewell', I

said to his family, and we went out, he and I, to the ground.

On the ground he asked, 'When are you likely to go back to your horneT I

replied, 'There is elsewhere I shall be going, but I shall pass here on the morning of

the fourth day from today, homeward'.

I took him by the hand, and said 'Thank you' .

12

I travelled to other worlds

Then we parted, and I stood there watching him go, but somehow he just

disappeared, as on the Thing.

I took my way home, all in wonder.

I had seen far more than swallows see from the air, perhaps as much as the

vultures that vanish from sight up in the sky.

REFERENCES

Call away, Henry. 1970a. The Religious System ofthe AmaZulu. Cape Town: C. Struik (Pty) Ltd.

Call away. Henry. 1970b. Nursery Tales, Traditions and Histories of the Zulus. in their own words/ a

translatIOn mtoEnglish and notes. Westport, Conn.: Negro University Press.

Faye, Carl. 1923. Zulu Referencesfor Interpreters and Students. Pietennaritzburg: City Printing Works Ltd.

Fave Papers, National Archives, Pietennaritzburg Depot. A141. (Box 7: ' "I Travelled to Other Worlds", By

a Zulu, As Told to Nimba Lulla McAyre'; 'Notes & Drafts, "When the British took Cetshwayo", as told

by Maphelu Zungu kaMkhosana, set down by Carl Faye'; 'The Taking of Cetshwayo, Told by Martin

Oftebro '; 'The Taking of Cetshwayo Zulu. Told by Chief Zimema Mzimela-Mnguni of Mthunzini, &

Recorded by Carl Faye').

Filter, H. and S. Bourquin. 1986. Paulma Dlamini: Servant ofTwo Kings. Killie Campbell Africana Library,

Durban, and University of Natal Press, Pietennaritzburg.

Klarer. Elizabeth. 1980. Beyond the Light Barrier, Howard Timmins Publishers.

Madela, Laduma. 1997. Zulu mythology as written and illustrated by the Zulu prophet Laduma Madela.

Ed. Katesa Schlosser. Kiel: Schmidt & Klaunig.

Mutwa. Vusamazulu Credo. 1996. Song of the Stars: The Lore of a Zulu Shaman. Stephen Larsen, ed.

Station Hill Openings, Barrytown Ltd.

NOTES

I. Notably, in the most recent publication by Katesa Schlosser (1997), who has documented extensively the

mythographies of the late Ceza lightning-doctor Laduma Madela, there is nothing in all Madela's rich

theogony which could be construed as UFO-related.

2. Mutwa's image has had quite a makeover since the days when the liberation movement blacklisted him as

a reactionary force propagating 'false consciousness'. He has become the de facto spokesman for all

things mythical and antiquarian in the African renaissance, and his controversial writings have come to

inspire many, including young South African filmmakers. (For a recent example, see the Weekly Mail

and Guardian 9 15 October 1998, Friday supplement, p4).

3. In Beyond the Light Barrier, set in the mid-'50s, a humanoid alien named Akon from the planet Meton

near Alpha Centauri, fathers a son on the author as one of 'only a few. chosen for breeding purposes

fl'om beyond [i\kon's] solar system, to infuse new blood into our ancient race' (:135). Mutwa mentions

having recently met and prayed with Klarer 'to the extraterrestrials on behalf of the people of Africa'. He

finds 'nothing unusual or so unearthly about Madame Klarer's story. There have been many women

throughout Africa in various centuries who have attested to the t.1.ct that they have been fertilized by

strange creatures from somewhere' (: 152).

4. Some might feel that this introduces an unsavoury ambiguity into a book whose underlying sentiments

may be told from the author's assertion that her hybrid offspring 'will not be born in this planet, where a

racialistic outlook submerges all sane and intellectual thought' (: 127). A milder dose of etlmocentrism

also enters into the present account. Although no direct reference is made to the physiognomy or

'ethnicity' ofthe aliens, their shipboard domestic pursuits (notably beadwork) reflect directly the culture

ofthe narrator.

S. Faye was sworn in as Interpreter before the Natal Supreme Court in 1919, and two years later entered in

the Union Civil Service List (Faye 1923: 6, 90, 9). Having at the age of seventeen met lames Stuart, the

archetype of the Zuluphile he himself was to become in the course of his career, he became right-hand

man of Chief Native Commissioner, Harry Lugg, in the 1930s, and at all important functions interpreted

for the royal house and leaders ofthe Zulu establishment.

6. The title is followed by 'World copyright reserved by Outspan', but there is no further detail, and no date

setting the somewhat daunting task of searching an un-indexed weekly magazine published from 1927

to 1957, throughout which entire period the piece may (or may not) have actually appeared in print.

13

/ travelled to other worlds

FUlthennore it can only be inferred from the occurrence of the name Zungu in the text that he was its

author. Nowhere in the document is it explicitly stated, but in view of the man's status, and his relation

with Faye. the assumption seems fair.

7. Maphelu's father Mkhosana was therefore closely linked to the royal house, and it was at his homestead

kwaNdasa (Place of Thriving) in the Ngome Forest that an English search party at last caught up with

and captured Cetshwayo following his flight after the Battle of Ulundi. Maphelu was present and gave

Faye an account of the event, titled "When the English Took Cetywayo The Story of Mapela Zungu"

(Faye Papers Box 7).

8. Faye makes much of Maphelu's 'oldentime Zuluness': he mentions his first encounter with 'the "magic"

of amakhandlela, candles', and how '[when] once Mapelu stayed as a guest at my home, occupying a

com.fortable outbuilding of brick, with all the facilities he needed ... (h)e had no wish to sleep on a bed

"upon the air", as he said, and preferred a mattress on the floor, near the fireplace'.

9. Faye clearly understood this event as having great symbolic importance for Zulu history, as he took down

two further accounts - one, on 6 May 1927, from an eyewitness on the 'other side' - the Zulu linguist

Maltin Oftebro, youngest son ofthe Norwegian missionary Ommund Oftebro CuMondi'), and a friend of

Faye's: the other on 6 July 1928 from Chief Zimema Mzimela-Mnguni of Mthunzini (Faye, Papers Box

7). It is worth noting that another Zulu account of this episode has appeared recently, from one of the

King's handmaidens, Paulina Dlamini (Filter & Bourquin).

ROBERT PAPINI

Exotic yet often colourless

The imported place names ofKwaZulu-Natal

Place names are bound up with the history of a country. Sometimes their etymology

and literal meaning are significant: for others, the origin the reason for the name,

or who gave it is more important. Then there are some for which none of this

information is available, but which exist simply as symbols. Some names are fixed

in public awareness by one moment in their history: Isandlwana, Majuba, Trustfeed.

Place names seem immutable. and yet they are surprisingly slippery. They come and

they go: they change in form; places may have more than one name: and the same

name may be given to more than one place.

Before considering some aspects of place names in K\vaZulu-Natal. a brief

explanation of naming categories is necessary. The term "geographical names". or

"toponyms. covers both natural features and those created by people, the latter

including everything from cities down to streets, squares and bridges. In South

Africa. there is an official advisory body to the government called the National Place

Names Committee (NPNC), currently within the Department of Arts, Culture,

Science and Technology. which since 1939 has supervised the official approval of

names in five categories: towns and suburbs. post offices. railway stations and

railway bus halts. The names of features in municipal areas such as streets and

parks are the responsibility of local government. There are, of course, many features

that fall outside these categories. such as airports. border posts, hospitals, dams,

nature reserves and highways. which are named by various government

departments. The names of natural features are recorded by the Department of

Surveys and Mapping in consultation with the NPNC. Some of the most colourful

names which most immediately reflect fashion and mood are those given to

privately owned entities such as farms and buildings, and settlements spontaneously

named by people but not submitted for formal approval. This article looks at some

names of to\\/ns. suburbs and settlements. railway stations. post offices and

topographical features. and includes names that have not been submitted to the

NPNC.

Successive European visitors and settlers have left traces of their languages and

countries of origin.

1

Though not much trace of the Portuguese remains. they did

make their mark with part of the current name for the province. Natal was given its

name by Vasco da Gama on Christmas Day, 1497. It was long thought, following

Eric Axelson, that da Gama actually gave the name to territory to the south of the

present border of the province. but Brian Stuckenberg has recently argued that the

lVata/1a 28. (1998), Elwyn lenkins pp. 14-22

15

Exotic yet ({[ten colourless

fleet had probably reached the vicinity of Hibberdene.::: The Voortrekkers kept this

name when they called their republic Natalia on 16 October 1840.

Some Portuguese names have shifted. Don Stayt records, 'When survivors of the

wreck St. Benedict in April 1554 reached the Tugela River on their long journey to

Mozambique they called it S1. Lucia. The name, however, was transferred to the

estuary further north by Manuel Teresreco when he surveyed the coast in 1575.' The

name Oro Point comes from the name meaning 'The Downs of Gold' which was

first given to St Lucia and then also moved, this time to Kosi Bay. Among the

Portuf,,'llese names that have not survived are Pescaria (,The Fisheries'), given to

what is now Durban by the St. Benedict party. Terra dos Fumos (,Land of Smoke'),

given to Tongaland by Manuel Perestrelo, and Rio dos Peixos for Cwebeni

(Richards Bay).

White settlers and missionaries gave names to new places, hitherto unnamed,

and to places that already had Zulu names. On the aesthetics of replacing the

original names. Revd Charles Pettman, best known for his dictionary of South

African English. Ajricanderisms, had this to say in 1914:

Travellers and others have often remarked upon the sameness and baldness of

much of our South African nomenclature: it is characterised generally by a want

of nice and accurate discrimination, by not a little repetition .... and also by a

considerable amount of real ugliness, testifYing to a lack of originality, a paucity

of idea. and to an a] most entire absence of poetic or aesthetic fancy on the part

of owners of the soil - some of the native names would have been vastly

preferable.

3

After the Portuguese came the Dutch. The spelling of most Dutch names was

changed to conform to Afrikaans orthography in the 1940s, such as Wasbank for

Waschbank. Though to be found all over the province, they are particularly

prominent in the north. The lown of Utrecht was originally called Schoonstroom

after the farm on which it was laid out in 1855. A year later it was renamed after the

town in the Netherlands. The original meaning of Utrecht, 'Outside meadow', was

irrelevant to the symbolism of this change, which was initiated by the local church

congregation.

There are distinct differences between the sort of names that Afrikaners and

English-speaking settlers gave. One is that places named after people in Afrikaans

usually have a generic element added, such as 'drif in Dejagersdrif. 'berg' in

Biggarsberg and 'burg' in Pietermaritzburg, whereas English-speakers preferred to

use the personal name on its own, as in Durban and Stanger, and sometimes\vith

the possessive. as in Gillitts (though they also created compound names, such as

Pinetown and Fynnland). The Afrikaans practice in fact conforms to the modern

rules of the NPNC, based on the international guidelines of the United Nations, that

place names based on personal names should include a generic element in order to

avoid confusion with an individual. Unfortunately, adding a generic does contribute

to the monotony that Pettman complained about, since South Africans do not choose

from a very wide repertoire and end up with something unimaginative, whether it be

'drif in Afrikaans or 'dale' in English.

16

Exotic yet often colourless

Another distinctive feature of Afrikaans names is complexity of meaning, such

as the use of abstract nouns to convey a statement (notably Vryheid), and names that

tell a story, such as Weenen, Berou, Hongerspoort, Wondergeluk and Toggekry

(meaning something like 'Got it after all'). Afrikaans nomenclature is also more

like Zulu than English in being more descriptive of the landscape. such as Kloof

Kranskop and Boomlaer.

English-speakers were very fond of repeating place names from Britain.

Sometimes this would be prompted by a perceived similarity, at other times by

nostalgia; less charitably, one might ascribe this practice to arrogance or lack of

imagination. From Ireland came Dargle and Donnybrook, and Scotland provided

many - Balgowan, Ballengeich, Kelso, Glencoe and Dundee. At least two Welsh

names can be found: Cymru itself, near Mtwalume, and Llewellyn, a station near

Mount Currie. England is the origin of scores, all with their evocative associations,

some well known, others obscure: Malvern, Henley, Sarnia, Mersey, Kearsney. One

name from the old country that did not endure was Beaulieu, which the settlers

found . embarrassing' and changed to Richmond. The Commonwealth is marked by

Ottawa and Malta.

An American connection is to be found in the names of mission stations founded

by Americans. Adams Mission was named after Dr Newton Adams, and Groutville

was named after Rev. Aldin Grout of the American Missionary Society, who

established his mission in 1844.

German missionaries and settlers brought German place names. New Gennany

was established in 1848 with its name in German, Neu-Deutschland, which was

subsequently translated as Gennany and later became known as New Germany.

Others that followed include New Hanover (1850) and Wartburg, and personal

names (Otto's Bluff and Ahrens). Clausthal was named by Bernard Schwikkard in

1852 after his wife's birthplace in Hanover. It is now commonly called Clansthal,

which illustrates how place names can be corrupted. Marburg, though intended by a

German mission for Gennan settlers, was settled in 1882 by a party of Norwegians,

who then gave a Scandinavian name to Oslo Beach. The Netherlands, already

mentioned, is also represented by New Guelderland, settled by eighty Dutch settlers

brought out by T. Colenbrander. Roman Catholic missionaries brought Genazzano

from Italy, and French Protestant missionaries created the name Mont-aux-Sources.

British names commemorate missionaries and clerics (Colenso), pioneers

(Dunn's Reserve, Curry's Post), the sponsors of the 1850 settlers (Byrne, Estcourt,

Lidgetton), military men (Richards Bay, after Sir Frederick Richards of the Royal

Navy), officials and public figures (Bulwer, Port Shepstone, Escombe, Harding,

Frere - the list is long). Royalty gave their names to three of the eight counties of

Natal, Victoria, Alfred and Alexandra, and Marina Beach is not nautical, but was

named after the Duchess of Kent in the 1930s. A couple of places bear a celebrity's

given name, which is odd, considering the fonnality of Victorian protocol, but

perhaps they were adopted because they are so distinctive: Pomeroy (Sir George

Pomeroy Colley) and Melmoth (Sir Melmoth Osborn). Ladysmith, everyone knows,

is named after Sir Harry Smith's wife, but the Aliwal Shoal is not connected with

him in the way that Aliwal North commemorates his victory in I n d i a ~ it was first

17

Exotic yet often colourless

recorded by the master of the ship Aliwal in 1849. In one odd instance, a postal

agency was named after two people, Denny Dalton, the surnames of two Australian

prospectors who had a profitable gold mine 84 km from Vryheid.

It is surprising how people's names incorporated in place names can become

misspelt over a period of time, in various places such as signboards and the usage of

different government departments. In the late 1980s the NPNC rectified the spelling

of the names of two passes in the northern part of the province. Lang' s Nek had

become known as Laing's Nek, even though it was named after William Timothy

Lang, who purchased the farm at its base in 1874. Another pioneer was Thomas

George Collings, who trekked with his wife from Oudtshoorn. They were the first

whites to use the pass that was named after him. However. it was variously spelled

as Collin' s Pass and Colling' s Pass, and this has now been standardised as Collings

Pass, \vithout an apostrophe.

Nowadays naming places after people is frowned upon in South Africa, because

it is realised that the names can become controversial following a change of regime.

Africans as well as whites have done it in the past, and the result is a colourful

record of our but perhaps the time has come to avoid being needlessly

divisive.

Indian languages are hardly represented in South Africa. One name with an

Indian element (now obsolete in the home country) is Bombay Heights. There is one

purely Indian one. but that was previously spelled incorrectly and had to be

corrected in 1994: it is Luxmi, a post office in Pietermaritzburg named after the

goddess of wealth. Generally, residential areas formerly reserved for Indians bear

English names such as Reservoir Hills, although the situation with street names is

very different. Research by Varijakshi Prabhakaran has revealed that although the

Indian suburbs of Durban have English names, they include '306 street names of

both Hindu and Muslim religious origins and of various [Indian] linguistic groups'. 4

The military were responsible for names such as the many 'Forts', most of which

have gone now, and names for obscure topographical features that were rendered

suddenly significant in some campaign, such as Advance Hill, near Colenso. The

45th Cutting and the suburb in which it is located, Sherwood, are two reminders of

the 45th Regiment, later known as the Sherwood Foresters, who formed the garrison

there from 1843 to 1860. Camperdown has an obscure military connection, named

by John Vanderplank after the British naval victory over the Dutch in 1787.

Other naming systems to be found in the province include those derived from

shipwrecks. Wrecks gave their names to Ambleside and Fascadale (places near Port

Shepstone named after wrecks of 1868 and 1895 respectively), the Annabella Bank,

once a hazard at the mouth of Durban Bay (after a wreck of 1856), and the Tenedos

Reef and Fort Tenedos (after a naval vessel damaged on the reef in 1879).

A whole informal naming system has been developed by the mountain climbing

fraternity for the peaks, cliffs and rock shelters of the Drakensberg, some features of

which have become official.

Other naming systems, which are rather rare in the province, are Biblical names

such as Berea, and classical names, represented by Verulam, named after the Earl of

Verulam, a sponsor of British settlers, whose title came from Verulamium, the

l8

Exotic yet often colourless

Roman town at St. Albans, and Halcyon Drift a hamlet near Mount Currie, in

which a classical name is incongruously linked with a very South African feature.

Some namers, and the meaning of some names, are unknown. Nobody knows

who gave European names to two of the region's best-known geographical features,

the Valley of a Thousand Hills and the Drakensberg. According to R.O. Pearse, the

name Drakensberg 'was in use well before the Voortrekkers came to Natal in

1837'." A name of unknown origin is Normandien, a pass and postal agency near

Newcastle. There are two celebrated names of disputed meaning. Wyebank and

Winklespruit. Wyebank could have been named after the River Wye in England, or

the 'Y -Bank'. an incline on the railway. or it could come from the Afrikaans '\-vye'

Cwide'). The origin of Winklespruit is hotly contested. It could come from the store

Cv.:inkel. as some people think the Zulus would have called jt)6 \vhich Sydney

Turner set up on the beach in 1875 to sell the contents of the wrecked schooner

TOl1fD that he had bought the rights to salvage: or it could be derived from the

periwinkles to be found in the lagoon. During the rule of the National Party

government this became one of the place names that were a focus of conflict

between English and Afrikaans. the other disputes being over the name

Voortrekkerstrand. which was given to the post office at Munster on the South

Coast. and the rival claims of Arniston and Waenhuiskrans in the Cape.

While the origins of some well-known places are forgotten, there have also been

names. and even settlements, that were stillborn or shortlived. The site of Port

Edward was bought by T.K. Pringle. who called it Banner Rest where he planned to

'lay down his banner'. There he laid out a township which it was proposed to call

KenningtoR after his name, Ken, but when it was established in 1924 it was

renamed in honour of Edward, Prince of Wales. Winder was a name originally

proposed for the new town of Ladysmith, after a trader, George Winder, but Lt

Governor Pine would not allow it as he had already decided to honour the wife of

the Governor of the Cape Colony. Springfield was the original name for Winterton,

\vhich also had to give way for the honouring of a VIP. named after the

Empress of France, was to have been a port that the New Republic planned to

establish at St. Lucia, but nothing came of it. In the 1960s Westlands and Morelands

were alternatives suggested for renaming Cato Manor (just as Sophiatown was

changed to Triomi), but they did not stick.

Two settlements of the immigrants of 1849-1851 that are ghost towns today are

York and Byrne. Blackburn was a hamlet on the south bank of the Umhlanga River,

north of Red Hill, that sprang up when a bridge was erected there in 1872, but it is

gone today. A town that has died in recent years is Burnside, which was still

flourishing in the 1950s while the coal mine operated there.

Countless names that were given in one language have been replaced by names

in another. This is most obviously the case with Zulu names which were replaced by

the 'official' names put in place by Afrikaans- and later English-speakers. In many

cases. the old names have not fallen into disuse, leading to a system of dual names

which is well known and recognised informally. Most Natalians know that

Thekwini (or Thekweni) is Durban. Where a new town was established with a non

Zulu name, Zulu-speakers have often developed their own version, such as Efilidi

19

f",xotic yet often colourless

for Vryheid. Since there are many dual place names in African languages and

English or Afrikaans in South Africa, and certain pairs in English 'and Afrikaans

are already recognised by the NPNC, thus creating a precedent, it will be incumbent

on the NPNC in the future to develop a policy on the recognition of these names that

is feasible. acceptable to all the people of the country, and in keeping with United

Nations guidelines on multiple naming.

In addition to English replacing Zulu. English replaced Afrikaans when

Houtboschrand gave way to Curry's Post. However, there have also been instances

of the power of colourful Zulu outweighing effete English names. An attempt at the

time of Captain Gardiner's map of 1835 to call the Umbilo River the Avon failed:

and although the township known as South Barrow, on the south bank of the

Umkomaas RiveL kept that name from 1862 to 1924, it was eventually superseded

by Umkomaas. The township of Ixopo. founded in 1878. was renamed Stuartstown

after the resident magistrate. Marthinus Stuart, was killed at the Battle of Ingogo,

but it later resumed its Zulu name (albeit in a form which is currently disputed).

Naming patterns since 1977

Place names are not simply part of the early history of the province. Names for all

sorts of ne"y entities continue to be given. and occasionally names are corrected or

changed. Some of these are officially recognised and recorded by the NPNC, while

others are recorded by other government agencies or remain unofficial. Names

approved by the minister on the recommendation of the NPNC include existing

names. such as those of suburbs. approved for the first time or given to new entities,

particularly post offices. The last published list, which covers the period 1977 to

1988. gives useful data on naming patterns in that period.

In the twelve years 1977-88 the Minister approved 1 274 names, of which 111

\vere in Natal and KwaZulu. The propOItion of names in English. Afrikaans and

other languages compared to names in African languages in the province was

fractionally more than the national proportion, namely forty-seven per cent to fifty

three per cent. Of the non-African names, eighty-two per cent were English, eleven

per cent Afrikaans. and seven per cent 'other' (which includes made-up names).

The history of development in the region during that period is reflected in the

number of names approved for entities in a particular town. Richards Bay received

two (Birdswood and Brackenham), and so did Pietermaritzburg (Lotusville and

Mysore Ridge). far the largest number for a single town went to Newcastle,

which received twenty-two new suburbs, racially segregated residential areas and

post offices. The kinds of names chosen for Newcastle reflect the tastes that

dominated the national scene at that time: seven 'parks'. two viBes'. a 'rand'. an

ugly coinage (Ferrax), Lennoxton. Schuinshoogte, Vlam. and a string of bland

cliches: Bergview, Fairleigh, Fernwood, Rickview, Riverside, Signal Hill, Sunny

Ridge and Sunset View. The 'parks' are where the commemoration of people is to

be found. in names such as BarI)' Hertzogpark and Viljoen Park.

The rest of the province saw its share of similarly nondescript names: Ashwood,

Brookdale, Forest Haven, Palmview, Waterberg Wood, Westmead. Local colour was

added to the conventional elements in Caneside and Mangrove Park. Ballitoville

20

Exotic yet often colourless

bucked the trend by officially shedding the 'ville' part. 'Modern' coinages

comprised Arbex, Con marine, Durmail and ProspectoR Indian names could be

spotted in Lotusville and Shastri Park, and Afrikaans, true to form, produced a

picturesque complex name, Meer en See.

8

The next published list of place names in the province is one published in 1992

by a non-governmental organisation. the Human Rights Commission. Entitled The

Tl'.'O South Africas: A People's Geography. it was an attempt to identify and map

the 'African. Indian and Coloured townships in South Africa'.

9

The list is probably

incomplete. especially when it comes to informal settlements. In Natal and

K waZulu, thirty-one per cent of the 143 names are in English, Afrikaans and other

languages, and sixty-nine per cent in Zulu. Most of those with non-Zulu names are

townships that were assigned to Indian and Coloured people, but there are a few

notable African ones as well, such as Limehill (once notorious as a 'dumping

ground') and Taylor's Halt.

The landmark year of 1994 saw the publication of a comprehensive list of

informal settlements in KwaZulu-NataL painstakingly collated from information

gathered for a research project on the subject that was undertaken by the Steering

Committee on Informal Settlement Development in Natal. 10 It contains 230 names,

of which 118. or fifty-one per cent, are in English. Afrikaans and languages other

than Zulu. Although these settlements are occupied almost entirely by Africans, this

proportion of non-Zulu names is higher than it was for all the official names

approved from 1977 to 1988. An explanation could be that many of the names by

which the informal settlements were recorded are simply descriptive of their

situation. such as Duffs Road Station. Effingham Quarry, Clare Hills Dump,

Stanger Municipal Dump and Stop 8, and the researchers have used English for

this. Cold official designations are also given in English, such as Block AK, Buffer

Strip, DD Section, and Ixopo Transit Camp. Included in this number are also all

those that have alternative names in Zulu, it being a feature of informal settlements

that many of them have several names.

11

The names of these settlements reflect a naming process that had been taking

place over several decades. Many of them are not originaL but take their name from

existing nearby places, of which farms or the names of the farmers are typical:

Brooks Farm, Glade Farm, Nenes Farm, Ngcobo's Farm, Pakkies Plaas. Missions

(such as Reichenau Mission and Springvale Mission), a factory (Sarmcol), and the

names of well-known places such as Mountain View and Plessislaer are used. Hence

old names have been given a new lease on life. as illustrated by the Dutch spellings

of Valsch River and Welbedacht.

A feature which is common among informal settlements in South Africa is the

transfer of place names from elsewhere, even when they are names which most

people would think had unpleasant associations. In KwaZulu-Natal there are at least

two like this: Soweto, situated near Inanda, and White City (which is a section of

Soweto in Gauteng as well as another township at Saldanha Bay). situated near

Nongoma.

It is difficult to tell the origins of some of the names without undertaking field

studies to obtain oral evidence, but a couple that obviously show that they were

21

Exotic yet often colourless

named by their inhabitants are Tin Town (also known as Gamalakhe) near Port

Shepstone, and Zig-Zag, a community of 200 people near Pinetown.

The names of informal settlements have not been submitted to the NPNC unless

they are part of existing residential areas that have been submitted. However,

developments in the 1990s are contributing to the official recording of these names

elsewhere. Both the Central Statistical Service and the Independent Electoral

Commission are mapping and recording all residential areas, and these

developments are monitored by the Department of Surveys and Mapping as part of

its ongoing updating of the official maps of the country. The SA Post Office has

declared its intention of ensuring that every citizen gets an address, and it is making

rapid progress in establishing post offices all over the country which will make this

possible. This is reflected in the lists of names which have been submitted to the

NPN C for official approval since the beginning of 1994. I :2

. The recent lists of the NPNC also reflect in other ways the transition that the

country is experiencing, It will be recalled that the NPNC currently has jurisdiction

over the names of towns and suburbs, post offices, railway stations and railway bus

halts. New legislation is expected to alter these, particularly extending jurisdiction

to the names of natural features, and giving the Commission (as it will be called)

powers to be more proactive over issues such as recording names regardless of

whether they have been submitted, and reviewing undesirable names. Clarity over

the role of provincial and local governments in the recognition of place names will

also be ensured.

In the meantime, almost the only category of name that has been submitted since

1994 is that of post offices, which are being set up at an unprecedented rate. The SA

Post Office works closely with the NPNC to ensure that the precepts of the NPNC

and the United Nations Guidelines are observed, ensuring that local communities

are consulted and invited to suggest names for their new post offices. The result is

that the new names reflect local demographics rather than ideology, as happened in

the past. There has been a drop in the proportion of new names in English,

Afrikaans and languages other than African languages since 1988: of the sixty-one

ne'" names approved for K waZulu-Natal between March 1994 and January 1998,

they represent thirty-nine per cent. Of those, the proportion of English names has

dropped slightly from eighty-two per cent to seventy-six per cent, and the proportion

of Afrikaans names has also dropped, from eleven per cent for 1977-88 to eight per

cent.

Among the new post offices are several with bilingual names: Buffelsdale,

Tugela Mouth, Umvoti Slopes, KwaPett, and perhaps Folweni could be included

here. since it is derived from the Africanised form of the Afrikaans word 'voor',

meaning 'furrow'. The old favourites among generic terms seem to be dwindling:

there is only one 'ville' (Copesville), one 'view' (Landview, in Pietermaritzburg)

and. remarkably. no 'park'.

The most interesting development arises from the new policy of the Post Office

to locate post offices in shops and shopping centres. Previously, the NPNC applied a

strict rule that official place names could not have a commercial connection because

that provided free advertising, but it has had to concede that although the names of

22

E,xotic yet often colourles.s'

shopping malls and shops may be regarded as commercial. it makes sense to the

public that the post offices bear the same name, Some of these names are quite

peculiar. and might not have found favour with the language purists of the NPNC in

the old days. but the new spirit of tolerance in the country has found its way here as

welL And so there are South Africans whose address in future will be a box number

at Four Three or Hyper by the Sea - a far cry from the cosy Paddocks and

lnglenooks that the residents of the province created for themselves in the past.

~ O T E S

The historieal inionnation in this article is drawn largely from Where on Earth? by Don Sta)1.

2 Bnan Stuekenberg. 'Vasco da Gama and the Naming of Natal", in NatalIa 2"7

3 Reverend Charles Penman, !Votes on South African Place Names, p. 37.

4 Varijakshi Prabhakaran. A Study of Indian Names for Streets in Durban, Nomina Afhcana. p. 5.

5. R.o. Pearse. Barrier o(Spears, p. i.

6. The word I(li) vlnkili is given as an alternative to the Zulu word isitolo for 'shop' in both the English and

LlIlu DlctiOnwy by Doke. Malcolm and Sikakana and the Zulu-English Dictionary by Doh and

Vilakazi.

7. Department of National Education, Gfjic/al Place Names In the Republic of South Africa. Approved

!9

T

1988.

8. For an analysis of national trends during this period. see E.R. Jenkins. PT Raper and LA Moller.

Changing Place Names. pp. 63-68.

<). Roddy Payne and Philip Stickler. The Two South Afncas.

10. The list was compiled by Rob Evans for Here to Stay, edited by Doug Hindson and Jetl'McCarthy, pp.

215-230.

11. For an analysis of national trends in the naming of infonnal settlements. see E.R. Jenkins et al ..

Place Names, pp. 70-76,

12. National Place Names Committee, 1994-1998,

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Doke. CM., Malcolm, D.McK. and Sikakana, lM.A English and Zulu Dictionary. Johannesburg:

llniversity ofthe Witwatersrand Press, 1982.

Doke. CM. and Vilakazi. B.W. Zulu-English DictiOnary. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand

Press. 1972.

Hindson. Doug and McCarthy. Jeft: eds. Here To Stay: Informal Settlements In KwaZulu-Natal. Durban:

Indicator Press. University of NataL 1994.

Jenkins. E.R .. Raper, P.E., M611er. L.A. Changing Place Names. Durban: Indicator Press. University of

!\ataL 1996.

Names Society of Southern Africa. C onClse Gazetteer ofSouth Afhca. Pretoria: Names Society of Southern

Africa. 1994.

National Place Names Committee. Official Place J"lames in the Republic of South AtTica. Approved

1988. Pretoria: Department of National Education (Culture). 1988.

National Place Names Committee. Unpublished Minutes of meetings. Pretoria: Department of Arts, Culture.

Science and Technology. 1994-1998.

Payne. Roddy and Stickler, Phi lip. The Two South ;ifricas: A People's Geography. Johannesburg: Human

Rights Commission, 1992.

Pettman, Reverend Charles. Notes on South African Place Names. Kimberley: Privately printed, 19 I 4.

Pearse. R.O. Barner ofSpears: Drama ofthe Drakensberg. Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1973.

Prabhakaran. Varijakshi. A Study of Indian Names for Streets in Durban. Nomina Afncana 11(2),

November 1997, 1-20.

Raper. P.E. DictIOnary ofSouthern Afncan Place Names, Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 1987.

Stayt. Don ['Wayfarer']. l.flhere on Earth? A GUide to the Place Names ofNatal and Zululand. Durban:

The Daily News, 1971.

Stuckenberg, Brian, 'Vasco da Gama and the Naming of Natal'. Natalia 27,1997, 19-29.

ELWYN JENKINS

Toponymiclapsesin

Zulu place names

Abstract

Toponymic lapses are faults or mistakes in place names which are found in maps,

records. telephone directories. signposts, etc. At face value they appear small. but on

closer inspection. one realises that they are vitally important. because names should

not fail to perform an unequivocal and unambiguous locational function. In

K waZulu-NataL as in other countries, difficulty arises when place names have been

wrongly spelt. Once incorrectly spelt. they fail to perform their locational function.

Toponymic lapses are caused by a number of factors. One major reason for incorrect

renderings in the spelling of names is the attempt to facilitate pronunciation by non

speakers of a particular language. Mispronunciation leads to strange and incorrect

spellings. and once a place name is wrongly spelt or discarded, the cultural message

also gets lost. Reasons for the incorrect spelling of place names may include

ignorance or inadequate knowledge of the grammar or latest orthographic rules of

the target language. marginalisation of the inhabitants of a particular area and

hypercorrection. Toponymic lapses also occur when the language in question is

underrated by cartographers, and names are corrupted in the drawing of maps, and

later in the inscription of signposts. Once that happens. the locational function of a

place name is compromised.

Richard. in a paper delivered at Quebec (1988:7), contends that 'names fill a

double role. a cultural role in terms of the message they convey . . . and they also

express the soul of the country in an exuberant and spontaneous manner. Names

have a technical role in terms of their locational values'.

This article will first consider some grammatical rules of Zulu'" to enable the

reader to follow the study more easily. Zulu, like all Bantu languages, has nouns

which are governed by a prefixal system. It will become clear, for instance, why is it

wrong for a speaker to exclude the locative prefix of a place name, referring to

Editor's note: Some writers (including Professor Zungu) now prefer to use the word isiZulu when

referring to the language in English discourse. While accepting that isiZulu is the language's own name

for itself ],.../atalta continues to use the accepted English lexical term Zulu, just as it would use the words

French. Gennan or Spanish to denote those languages, and not Francais, Deutsch or Espagnol.

.Vata/IQ 28. (1998), Phyllis 1.N. Zungu pp. 2 3 ~ 3 3

24

Toponymic lapses in Zulu place names

ThekwinL instead of EThekwini, Mgungundlovu instead of Emgungundlovu, etc.

The treatment of nouns will be followed by a discussion of toponymic lapses caused

by incorrect spelling. Parallel names of some places and institutions will be dealt

with. as will a few place names which have been Africanised.

This is an ongoing study but it is hoped that this article will bring to light some

of the mistakes of the past, such as the lack of aspiration in most place names with

th. ph. kh (Pumula instead of Phumula, Isipingo instead of Isiphingo, etc.), but it

will exclude orthography which changes from time to time. It is also hoped that it

will be a contribution to the history of the Province of KwaZulu-Natal and to the

study of onomastics.

The prexifal System of Zulu nouns

Class e.g.

umu-, um umuntu person

(a) u ugogo granny

2 aba-, abe- ab abantu people

2(a) 0 ogogo grannies

3 umu-, um umunga mimosa tree

umbango contention over a claim

3(a) u uswidi sweet (a confectionery)

4 imi iminga mimosa trees

5 Hi-, il itheku male with one testicle

6 ama-, ame amanzimtoti sweet water

7 isi-, is isiphingo thin plaited branch of a tree

used for thatching a hut

9 iN imbokodo round stone

10-8 iziN izimbokodo smooth round stones

11 ulu ulwandle ocean

12-13 (Not found in Zulu)

14 ubu ubuhle beauty

15 uku ukusa dawn

The formation of place names from nouns

Place names are in effect locative adverbs because they give the location of an entity.

A simple rule which converts nouns to locatives is to modify all the initial vowels of

the nouns from class 3 onwards, into e- (except for class 11 where the u- becomes 0-.

Classes 1, la, 2, 2a and 3a prefix k and ku-. This process changes nouns into

adverbs of place or time and is indicated by to, in, at, from, by.

Suffixation

Most Zulu nouns suffix -ini on conversion to the but there are also

exceptions. Classes 1, la, 2, and 2a hardly ever suffix -ini. Nouns of classes 3 to 15

usually suffix -ini to the final vowel. For instance, a noun ending with -a+ini

becomes -eni.

Toponymic lapses in Zulu place names

25

-a+ini>-eni -a:izinqola ezinqoleni

-e+ini>-eni -e:isikole esikoleni

-i+ini>-ini -i: umuziwezinto emziniwezinto

-i+ini> -i:ithusi ethusini

-o+ini>-weni -0:izimbokodo ezimbokodweni

-u+ini>-wini -u:itheku ethekwini

When using place names derived from personal nouns, (viz. those in noun

classes 1 and la) to indicate motion towards, the prefix ku- is used and this is

followed by the locative formative -a- , e.g. u+a>wa

ku+a+Makhutha > K waMakhutha

ku+a+Mashu > K waMashu

ku+a +dokotela > K wadokotela

It must be emphasised that not all Zulu place names undergo suffixation, as is

also the case with nouns. Some place names derive their existence from verbs,

idiophones, etc., and they carry in them the history of the nation. In other words,

there is more to a name than meets the eye.

3 emngeni < emungeni < umunga (at a place with mimosa trees)

embangweni < umbango (at a place of dispute)

3a KwaSwidi < uswidi (at a factory where sweets are manufactured)

4 emngeni < iminga (at a place with mimosa trees)

5 eThekwini < itheku (at a place shaped like a male organ with one testicle

6 eManzimtoti < amanzimtoti (at a place with sweet water: Amanzimtoti)

7 eSiphingo < isiphingo (at Isiphingo) (Name of the Luthuli Chief)

9 embokodweni < imbokodo (a place with a smooth round stone)

8-10 ezimbokodweni < izimbokodo (a place with smooth round stones)

11 othongathi < uthongathi (ulu-) (at UThongathi)

olwandle < ulwandle (ulu-) (at the sea)

14 ebusuku < ubusuku (at night)

ebusweni (on the face)

15 ekuseni (in the morning)

ekudleni (in the food)

Orthographic rules (adapted from IsiZulu Terminology and Orthography No.4

(1993)

Capitalization of place names

This should follow definite orthographic rules, adapted from isiZulu Terminology

and Orthography No. 4 (1993). The locative prefix kwa- can indicate 'to, in, at,

from' the property, residence, firm, store, homestead, surname etc. Place names

beginning with the locative prefix kwa- or ka-:

KwaZulu in Zululand

KwaMashu at the place of Sir Marshall Campbell

KwaMakhutha at Makhutha location.

26

Toponymic lapses in Zulu place names

KwaGqwathaza

KwaZungu

at the place of Gqwathaza (this is Zulu name for

Highflats).

at the Zungu residence

In the case of all the other place names, the first letter after the initial vowel will

be a capital. The first part suggests the noun whence the locative is derived and the

second part is the locative indicating in, at to, from e.g.:

iTheku> eThekwinL iGoli> eGolL uLundi> oNdini. uMlaza> eMlaza.

uLvvandle> oLwandle. uThongathi> oThongathi. iSikhala> eSikhaleni. uMthetho>

eMthetlnveni. aManzimtoti> eManzimtoti. uMuziwezinto> eMziniwezinto.

iZinqola> eZinqoleni. uMngeni> eMngeni. aMahlongwa> eMaHlon!,'Wa.

iSandlwana> eSandhvana. iGoli> eGoli, etc. For example. a speaker might say

Ngihlala eThekwini (1 live in Durban): Ngiya eMgungundlovu (I am going to

Pietermari tzburg).

In the official names of schools, post offices. etc .. the first letter of the word is

also capitalised, e.g.: UMngeni. AManzimtotL ITheku, EThekwini. UMlazi.

ONdini. UThongathL UMuziwezinto, EZinqoleni. AManzimtoti. ISiphingo.

ONgoye. ULundL UMlaza, UThongathi, UMkhomazi etc.

There are many examples where the etymology of the place name is obscure or

totally lost. The following examples are cited.

Toponymic lapses caused by incorrect pronunciation

Ndwedwe instead ofSondoda

There is a high ridge in the MaQadini area near Inanda which is now known as

Ndwedwe. where the present Ndwedwe police station is situated. The original name

of this ridge was Sondoda (father of men), but because the foreigners could not

pronounce Sondoda, they simply named the ridge Ndwedwe not even keeping the

vowel sounds of the original. This name soon appeared on signposts and in all

government records and compelled the people to use the strange and meaningless

word.

In former times. Africans were very ready to accept things which were non

African. They did not mind if a name had no significance for them as long as it was

non-Zulu or non-African. Proof of this will be found in the names of elderly people

today. which are mostly of European origin. Pupils used to report their

schoolfellows for calling them by their home names (igama lasekhaya) on the school

premises and the culprits were often punished. Consider the names of elderly

African people throughout Africa which are of European origin. It is only now that

people are realising the importance of their African names and taking pride in

calling themselves by such names. Below is a discussion of a few examples of place

names, most of which are found in the South Coast of KwaZulu-Natal. They have

been wrongly written, but for years people did not mind using them as they were. It

did not matter to them because they were written by people whom they regarded as

being more enlightened than they.

27

Toponymic lapses in Zulu place names

EZingolweni or Ezinqoleni

This place is inland from Port Shepstone, to the west. It was the home of the Cele

clan and was originally known as KwaCele, a place belonging to Chief Cele or a

place occupied by the Cele clan. Later, white people arrived in this area and

constructed a railway station. It was a terminus, and many railway carriages and

trucks coaches were parked there. When the Cele people saw these, they named the

place Ezinqoleni - the place of many wagons or coaches. Because the cartographers,

or \vhite people generally, failed to pronounce the -nq- 'click' sound in EZinqoleni,

they adapted the place name to Ezingolweni, which has no significance or meaning

to a Zulu speaker, whereas EZinqoleni records the history of the area .

. \/Boginnvini or Ezimbokodweni

Ezimbokodweni is the name of a river, and a town on the upper South Coast. The

place name UMbogintwini, is lexically meaningless to a Zulu-speaking person as

compared to EZimbokodweni. Ezimbokodweni means a place where many small

round stones used for grinding corn and mealies, are obtained. Even an uninformed