Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Malone Road To The White House Lecture II Campaign Finance

Uploaded by

cmalone410Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Malone Road To The White House Lecture II Campaign Finance

Uploaded by

cmalone410Copyright:

Available Formats

Lecture II Campaign Finance Dr. Christopher Malone I.

Introduction The Cost of campaigning: The cost of campaigning in American politics has risen drastically in the World War II period, and especially since the 1960s and 1970s which coincides with the importance of the primary in presidential elections. Not surprisingly, candidates must begin campaigning earlier and must do it for the most part through paid advertisements. See Table 2-2 on page 34 of the Wayne book: with the increase in the number of primaries across the country and the need to advertise on television in the general election, the cost of presidential nominations has increased drastically. In 2000, the candidates spent about $600 million; in 2004 the amount spent on the presidential campaign was about $1 billion. In 2008, the combined amount of spending on the presidential campaign by candidates was $1.32 billion. When outside spending is factored it, the total was about $2.4 billion. II. Costs and Presidential Nominations Before the changes in the primary system in the early 1970s, candidates spent little money on the primaries. Today, however, more money is spent during the primary season than during the general election. This begs the question: why are elections so expensive today? Three reasons: a. Mass Media: Campaigns that were once waged in the printed press - and hence virtually free for the candidates - are now waged in the electronic media. Newspapers before the Civil War were partisan, i.e., they were printed by political parties and did not even claim to be objective. Campaigns were thus financed by advertisements and the paying customer. By the early 20th century, campaign costs started to rise with each new invention: the first radio campaign was waged in 1924. 1952 saw the first television advertisement in a presidential campaign and the first time a presidential convention was aired. In 1960, the candidates for president (Kennedy and Nixon) debated on television for the first time, as we saw earlier this semester. In 2000, the parties and candidates had spent about $205 million on television ads. In 2004 and 2008, that figure was over $600 million. b. Polling/Staffing: The use of polling and all of the consultants in a modern presidential campaign have also increased the costs of campaigns over the last 30 years. Why has the staff of the candidates become so important? Again, we have to understand the impact of the expanded and extended primary system. In order to capture the nomination, you need to win in the primaries; in order to win in the primaries, you need name recognition; in order to have name recognition, you need a ton of money. But candidates also need to take the pulse of more of the American public because voters now decide in the primary, and they need to take the pulse much longer. And then they need to hone their message. Think about it: in September/October 2011 (as I write this) we are over a year away from the next presidential election, and polling has already been used extensively. c. Fund-raising: The way candidates raise money today is quite different than in the past. We will get to the finance system in a minute: for now, let us say that in the past candidates 1|Page

could count on a large amount of money from a small amount of contributors - such as the Vanderbilts, the Carnegies, the Rockefellers. Today, presidents must get a large number of contributors giving a small amount of money. They must cast their nets wider, and to do so they need a whole fundraising army. Direct mailings have been the most costly, but this method has also become quite beneficial. Email solicitations have cut down the cost of raising money, but studies have shown that the response rates on email fundraising is very low. III. Sources of Support: Who Pays, How much do they Pay, and What do they get for their money? We want to know three questions about campaign finance: who pays? How much do they pay? And what do they get for their money? Throughout most of electoral history, campaigns were funded by large contributions from a small number of very wealthy Americans. This system of campaign financing lasted up to the early 1970s. Richard Nixon's campaigns were financed with large contributions, say, $10,000 or more. In fact, in 1972 the NixonMcGovern campaigns raised a combined $27 million from fewer than 200 donors. Thats an average of $135,000 per campaign contribution! This began to raise serious questions about the democratic character of presidential elections. In short, how could a candidate who claims to speak for all the people be responsive to both the public at large and individual benefactors? Put another way, is the principle of one man, one vote violated with large campaign contributions from wealthy donors? IV. Finance Legislation: FECA In the early 1970s, Congress enacted campaign finance reform designed to do three things: 1) reduce this dependence on large donors and encourage a broad base of public support for presidential candidates; 2) equalize the playing field for Democrats and Republicans; and 3) strengthen the twoparty system. a. Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA). It 1. set ceilings on the amount of money presidential and vice presidential candidates (and their families) could spend on their campaigns. 2. It allowed for the creation of PAC's - political action committees - which consisted of a group who solicited voluntary contributions to be given to a party or a candidate. 3. FECA also established procedures for public disclosure of funds. b. The Revenue Act of 1971. This piece of legislation created tax credits and deductions in order to encourage private contributions, and it also set up a public presidential election campaign fund - initially $1, but raised to $3 in recent years (1993). V. Watergate 2|Page

These laws were not set to go into effect until 1976. However, in the 1972 presidential campaign one of the biggest political scandals in American history occurred - Watergate. While Watergate involved an intricate affair of break-ins, cover ups and pay-offs, it also led to reforms in campaign finance laws. For Nixon's reelection committee (CREEP) had wads of cash in safes from individual and corporate donors, most of whom were anonymous. This cash was used to pay off those involved in the break in, and also led to Nixon's resignation in 1974. VI. FECA Amendments of 1974 The FECA Amendments of 1974: 1. Set public disclosure provisions, 2. contribution ceilings for both individuals and groups, 3. spending limits for the campaigns, 4. federal subsidies for the major party candidates in the nomination process and 5. complete funding for the general election. 6. limited the amount candidates could contribute to their own campaigns, and 7. set up a six person Federal Election Commission (FEC). VII. Buckley v. Valeo: Money Equals Free Speech Immediately the Amendments of 1974 to FECA were challenged in court on the grounds that limiting personal spending in a campaign is a violation of the First Amendment right to the freedom of Speech. The Supreme Court did two things in the ruling: first, it upheld in principle the notion that Congress can regulate campaign spending, but second, it struck down the limits placed on the amount of personal or organizational spending on a campaign. In other words, it set up the voluntary system we have today for presidential elections, which states that any presidential candidate that accepts public matching funds is limited on the amount of money he or she can spend on his or her own campaign. If a person does not accept public matching funds, he or she can spend as much as they want. The decision did not apply to Congressional races, which is why you see many candidates spending their vast fortunes for runs for Congress. VIII. Subsequent FECA Amendments After Buckley v. Valeo, Congress was forced to amend FECA once again. It set a voluntary limit of $10 million on presidential campaigns, adjusted for inflation pegged to 1974. Candidates did not have to accept public matching funds, but if they did they were to stay beneath the spending cap. In 1979, the law was amended once again and raised the minimum amount of a contribution which had to be reported to the Federal Election Commission (known as the FEC, a six person committee 3|Page

comprised of 3 Democrats and 3 Republicans). More importantly, the 1979 amendments allowed political parties to raise unlimited amounts of money for party building activities such as voter registration and voter turnout. Alas, the concept of soft money was born. While seemingly unimportant at the time, this provision created a gigantic loophole for the parties to essentially raise unlimited and unreported amounts of money. In fact, parties did not have to disclose contributors until 1992. In 1993, FECA was amended to increase the voluntary contribution of taxpayers from $1 to $3. Still, taxpayer contribution to the presidential campaign fund has continued to fall off 28.7% of the total allocated funds in 1980 to just 12% today. IX. Campaign Finance Legislation Provisions Before and after McCain Feingold Law In 2002 Congress passed the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BRCA), more popularly known as McCain-Feingold (named after the Senate co-sponsors) which went into effect on midnight, November 6th, 2002. BCRA prohibited soft money fundraising by national party committees, federal candidates and federal officeholders, and required state and local party committees to use hard money to pay for many kinds of federal election activity. BCRA also limited the ability of corporations, including many advocacy organizations, to pay for broadcast ads that mention federal candidates during the time periods just before an election. The law was immediately brought to court, In December 2003 the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of BCRA in the case McConnell v. FEC. The Court held the following: The Court upheld the BCRAs most contested provisions, the regulation of "soft money" and "electioneering communications," as well as the "coordination" provision. The Court also held that regulation of "electioneering communications"broadcast ads that refer to a federal candidate 30 days before a primary or 60 days before a general electionwas not precluded by the prior holding in Buckley v. Valeo which limited regulation of political speech to that which employed express words of electoral advocacy. The Court also determined that the "electioneering communication" provision did not restrict much otherwise permissible speech. Therefore, the 30/60 day provision was not unconstitutionally overbroad in scope. Finally, the Court held that political activity coordinated with political candidates and parties can be regulated even in the absence of agreement to coordinate or formal collaboration. For example, spending at the "request" or "suggestion" of a candidate or party may establish coordination. However, the Court struck down the BCRAs requirement that national parties choose between coordinating with candidates and making independent expenditures.

X. The Rise of 527s 527 groups are tax-exempt organizations that engage in political activities, often through unlimited soft money contributions. Most 527s are advocacy groups trying to influence federal elections through voter mobilization efforts and so-called issue ads that tout or criticize a candidate's record. 527s must report their contributors and expenditures to the IRS, unless they already file identical information at the state or local level.

4|Page

In 2004 527s raised more than $600 million. It has become the main way big donors give to the political process. In 2006 for example, at least 60 individuals gave over $175,000 to 527s. XI. Citizens United (2010): Corporations are People Too In 2010, the Supreme Court revisited BCRA (McCain-Feingold) and overturned an important part of the law regulating political activity of corporations and unions. In the case Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission (2010), the Court overturned a provision of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act prohibiting unions, corporations and not-for-profit organizations from broadcasting electioneering communications within 60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary election violates the free speech clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. United States District Court for the District of Columbia reversed. In his majority opinion, Justice Kennedy wrote: "If the First Amendment has any force, it prohibits Congress from fining or jailing citizens, or associations of citizens, for simply engaging in political speech." Kennedy went on to suggest that corporations act or should be seen as acting like a political associations or clubs with political viewpoints. XII. Contribution Limits

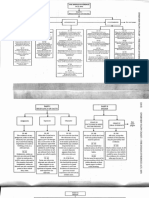

Contribution Limits 2011-12

To each candidate or candidate committee per election Individual may give $2,500* To national party committee per calendar year $30,800* To state, district & local party committee per calendar year $10,000 (combined limit) To any other Special Limits political committee per calendar year[1] $5,000 $117,000* overall biennial limit:

$46,200* to all candidates $70,800* to all PACs and parties[2]

National Party Committee may give State, District & Local Party Committee may give PAC (multicandidate)[4] may give

$5,000

No limit

No limit

$5,000

$43,100* to Senate candidate per campaign[3] No limit

$5,000 (combined limit) $5,000

No limit

No limit

$5,000 (combined limit) $5,000

$15,000

$5,000 (combined limit)

No limit

5|Page

PAC $2,500* (not multicandidate) may give Authorized Campaign Committee may give $2,000[5]

$30,800*

$10,000 (combined limit) No limit

$5,000

No limit

No limit

$5,000

No limit

* These contribution limits are increased for inflation in odd-numbered years. 1. A contribution earmarked for a candidate through a political committee counts against the original contributors limit for that candidate. In certain circumstances, the contribution may also count against the contributors limit to the PAC. 11 CFR 110.6. See also 11 CFR 110.1(h). 2. No more than $46,200 of this amount may be contributed to state and local party committees and PACs. 3. This limit is shared by the national committee and the Senate campaign committee. 4. A multicandidate committee is a political committee with more than 50 contributors which has been registered for at least 6 months and, with the exception of state party committees, has made contributions to 5 or more candidates for federal office. 11 CFR 100.5(e)(3). 5. A federal candidate's authorized committee(s) may contribute no more than $2,000 per election to another federal candidate's authorized committee(s). 2 U.S.C. 432(e)(3)(B).

XIII. Primary Matching Funds

See page 48 for the amount of public matching funds. Partial public funding is available to Presidential primary candidates in the form of matching payments. The federal government will match up to $250 of an individual's total contributions to an eligible candidate. Only candidates seeking nomination by a political party to the office of President are eligible to receive primary matching funds. In addition, a candidate must establish eligibility by showing broad-based public support. He or she must raise in excess of $5,000 in each of at least 20 states (i.e., over $100,000). Although an individual may contribute up to $2,500 to a primary candidate, only a maximum of $250 per individual applies toward the $5,000 threshold in each state. Candidates also must agree to:

Limit campaign spending for all primary elections to $10 million plus a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA).This is called the national spending limit. Limit campaign spending in each state to $200,000 plus COLA, or to a specified amount based on the number of voting age individuals in the state (plus COLA), whichever is greater. Limit spending from personal funds to $50,000.

The campaign finance law exempts the payment of some expenses from the spending limits. Certain fundraising expenses (up to 20 percent of the expenditure limit) and legal and accounting expenses incurred solely to ensure the campaign's compliance with the law do not count against the expenditure limits. 6|Page

Once they have established eligibility for matching payments, Presidential candidates may receive public funds to match contributions from individual contributors, up to $250 per individual. The contributions must be in the form of a check or money order. (Purchases of tickets to fundraisers and contributions collected through joint fundraising are matchable contributions, but loans, cash contributions, goods or services, contributions from political committees and contributions which are illegal under the campaign finance law are not matchable). Even if they no longer campaign actively in primary elections, candidates may continue to request public funds to pay off campaign debts until late February or early March of the year following an election. (However, to qualify for matching funds, contributions must be deposited in the campaign account by December 31 of the election year.) Eligible candidates may receive public funds equaling up to half of the national spending limit for the primary campaign. Because candidates receive many nonmatchable contributions, such as those from political committees, they generally raise more money than they receive in matching funds.

XIV. General Election Funding

The Presidential nominee of each major party may become eligible for a public grant of $20 million (plus a cost-of-living adjustment) for campaigning in the general election. To be eligible to receive the public funds, the candidate must limit spending to the amount of the grant and may not accept private contributions for the campaign. Private contributions may, however, be accepted for a special account maintained exclusively to pay for legal and accounting expenses associated with complying with the campaign finance law. These legal and accounting expenses are not subject to the expenditure limit. In addition, candidates may spend up to $50,000 from their own personal funds. Such spending does not count against the expenditure limit. Minor party candidates and new party candidates may become eligible for partial public funding of their general election campaigns. (A minor party candidate is the nominee of a party whose candidate received between 5 and 25 percent of the total popular vote in the preceding Presidential election. A new party candidate is the nominee of a party that is neither a major party nor a minor party.) The amount of public funding to which a minor party candidate is entitled is based on the ratio of the party's popular vote in the preceding Presidential election to the average popular vote of the two major party candidates in that election. A new party candidate receives partial public funding after the election if he/she receives 5 percent or more of the vote. The entitlement is based on the ratio of the new party candidate's popular vote in the current election to the average popular vote of the two major party candidates in the election. Although minor and new party candidates may supplement public funds with private contributions and may exempt some fundraising costs from their expenditure limit, they are otherwise subject to the same spending limit and other requirements that apply to major party candidates. XV. Presidential Spending Limits "If the Election Were Held in 2011" As one of the conditions for receiving public funding, Presidential candidates must agree to abide by certain spending limitations. The limits applicable to publicly funded candidates running in 2012 will not be available until early in 2012. In the meantime, "if the election were held in 2011:" 7|Page

General Election Limit: $88.45 million Overall Primary Limit: $44.22 million

XVI. Sources of Revenue for Presidential Contenders There are four ways candidates raise money for the presidency: a. Individual contributors: $2,500 limit is placed on individuals. $50,000 limit on candidate and members of family, b. Non-party committees/groups: PACs can donate up to $5,000 to a candidates campaign. c. Matching Funds: Candidates can choose to receive matching funds if they abide by FEC rules and spending limits. (See pages 47-48 of Wayne book). The total spending limit in 2008 was $56.7 million. In 2012, that will increase to about $60 million. If they abide by the rules, candidates will receive public matching funds. In 2000, the matching funds were set at $61 million for each major party candidate. In 2004, that figure increased to $73 million. The matching figure for 2008 was $85 million and for 2012 it will in a likelihood be over $88 million. d. Soft Money: McCain Feingold placed a limit on the amount of money that can be given to political parties, but 527s stepped into this lurch in 2004. Campaign finance experts predict that the Citizens United case will lead to a flood of corporate money in the 2012 election. XVII. Money and Electoral Success The question of how money affects the outcomes of campaigns is vital to not only the issue of campaign finance, but to the question of democracy itself. Again, one person one vote is the principle of American elections. The problem comes after the election, where possibly big donors have more influence. In America in other words, we are all equal only on election day. In between elections, some are more equal than others. 1. Who has or gets the money? Two types of candidates one is the personally rich, the other is the frontrunner who can raise money for various reasons, one of which is electability. 2. Does Money make the difference? As Wayne points out on page 66, 21 of 29 winners between 1860 and 1972 (before campaign finance legislation) outspent his opponent. Republicans outspent Democrats 25 out of 29 times, and the Democrats won the 4 times that they outspent the Republican. Obama outspent his opponent by nearly 2-1 in 2008. But there are other factors: incumbency, message, the economy, world affairs. While money matters, we have to consider these other variables in electoral outcomes as well.

8|Page

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Race, Class, and Gender in The United States An Integrated Study 10th EditionDocument684 pagesRace, Class, and Gender in The United States An Integrated Study 10th EditionChel100% (10)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Asme B5.38-1958Document14 pagesAsme B5.38-1958vijay pawarNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement Analysis: Submitted By: Saket Jhanwar 09BS0002013Document5 pagesFinancial Statement Analysis: Submitted By: Saket Jhanwar 09BS0002013saketjhanwarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document59 pagesChapter 1Kim Canonigo LacostaNo ratings yet

- Criminal InformationDocument2 pagesCriminal InformationVal Justin DeatrasNo ratings yet

- Partnership Deed Day of February Two Thousand Nineteen in BetweenDocument6 pagesPartnership Deed Day of February Two Thousand Nineteen in Betweenradha83% (6)

- 12 First Optima Realty Corp vs. SecuritronDocument2 pages12 First Optima Realty Corp vs. SecuritronFloyd Mago100% (1)

- Feb Month - 12 Feb To 11 MarchDocument2 pagesFeb Month - 12 Feb To 11 MarchatulNo ratings yet

- Presidential Debate Discourse: Dr. Christopher Malone Associate Professor of Political Science Pace UniversityDocument5 pagesPresidential Debate Discourse: Dr. Christopher Malone Associate Professor of Political Science Pace Universitycmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VIIDocument4 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture VIIcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VIII Debate DiscourseDocument3 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture VIII Debate Discoursecmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VIII Debate DiscourseDocument3 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture VIII Debate Discoursecmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VIIDocument20 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture VIIcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VIIDocument4 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture VIIcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VIDocument23 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture VIcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VDocument9 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture Vcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VIDocument10 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture VIcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VIDocument23 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture VIcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture V The ConventionDocument2 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture V The Conventioncmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture VIDocument10 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture VIcmalone410No ratings yet

- Comparison of The 2008 Major Party PlatformsDocument5 pagesComparison of The 2008 Major Party Platformscmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture IVDocument20 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture IVcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture IV Nomination ProcessDocument6 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture IV Nomination Processcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture 1Document20 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture 1cmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture III The Political EnvironmentDocument21 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture III The Political Environmentcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture 2Document24 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture 2cmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture IIIDocument48 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture IIIcmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture 1Document5 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture 1cmalone410No ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Fall 2011 SyllabusDocument7 pagesMalone POL 296N Fall 2011 Syllabuscmalone410No ratings yet

- The Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Manual by Muhammad Mahbubur Rahman PDFDocument246 pagesThe Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Manual by Muhammad Mahbubur Rahman PDFMd. Shiraz JinnathNo ratings yet

- Newspaper Publication I Ep FDocument3 pagesNewspaper Publication I Ep FRajNo ratings yet

- J2534 VCI Driver Installation GuideDocument3 pagesJ2534 VCI Driver Installation GuideHartini SusiawanNo ratings yet

- Stock Investing Mastermind - Zebra Learn-171Document2 pagesStock Investing Mastermind - Zebra Learn-171RGNitinDevaNo ratings yet

- Inter Regional Transfer FormDocument2 pagesInter Regional Transfer FormEthiopian Best Music (ፈታ)No ratings yet

- Irr SSMDocument25 pagesIrr SSMPaulo Edrian Dela PenaNo ratings yet

- Norman Dreyfuss 2016Document17 pagesNorman Dreyfuss 2016Parents' Coalition of Montgomery County, MarylandNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Act: Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No. 11036Document20 pagesMental Health Act: Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No. 11036RJ BalladaresNo ratings yet

- CIAP Document 101Document128 pagesCIAP Document 101Niel SalgadoNo ratings yet

- J.B. Cooper by Dr. S.N. SureshDocument16 pagesJ.B. Cooper by Dr. S.N. SureshdrsnsureshNo ratings yet

- 5 Engineering - Machinery Corp. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 52267, January 24, 1996.Document16 pages5 Engineering - Machinery Corp. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 52267, January 24, 1996.June DoriftoNo ratings yet

- Cyber LawsDocument19 pagesCyber LawsAnonymous vH4lUgV9No ratings yet

- Rr310106 Managerial Economics and Financial AnalysisDocument9 pagesRr310106 Managerial Economics and Financial AnalysisSRINIVASA RAO GANTANo ratings yet

- Fourth Trumpet From The Fourth Anglican Global South To South EncounterDocument4 pagesFourth Trumpet From The Fourth Anglican Global South To South EncounterTheLivingChurchdocsNo ratings yet

- 5 PDFDocument116 pages5 PDFSaranshNinaweNo ratings yet

- K. Anbazhagan v. State of Karnataka & Ors PDFDocument49 pagesK. Anbazhagan v. State of Karnataka & Ors PDFHenry SsentongoNo ratings yet

- SAP FICO Course Content by Archon Tech SolutionsDocument4 pagesSAP FICO Course Content by Archon Tech SolutionsCorpsalesNo ratings yet

- Kodak Brownie HawkeyeDocument15 pagesKodak Brownie HawkeyeLee JenningsNo ratings yet

- Kevin Murphy V Onondaga County (Doc 157) Criminal Acts Implicate Dominick AlbaneseDocument11 pagesKevin Murphy V Onondaga County (Doc 157) Criminal Acts Implicate Dominick AlbaneseDesiree YaganNo ratings yet

- Trenis McTyere, Lucille Clark v. Apple, Class ActionDocument21 pagesTrenis McTyere, Lucille Clark v. Apple, Class ActionJack PurcherNo ratings yet

- Inputs Comments and Recommendation On CMC Rationalized Duty Scheme of PNP PersonnelDocument3 pagesInputs Comments and Recommendation On CMC Rationalized Duty Scheme of PNP PersonnelMyleen Dofredo Escobar - Cubar100% (1)

- Relevancy of Facts: The Indian Evidence ACT, 1872Document3 pagesRelevancy of Facts: The Indian Evidence ACT, 1872Arun HiroNo ratings yet