Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Corporate Governarce and Human Resource Managelemt

Uploaded by

xaxif8265Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Corporate Governarce and Human Resource Managelemt

Uploaded by

xaxif8265Copyright:

Available Formats

Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Oxford, UKBJIRBritish Journal of Industrial Relations0007-1080Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006September 2006443541567Articles

Corporate Governance and Human Resource ManagementBritish Journal of Industrial Relations

British Journal of Industrial Relations 44:3 September 2006 00071080 pp. 541567

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

Suzanne Konzelmann, Neil Conway, Linda Trenberth and Frank Wilkinson

Abstract This paper investigates the effect of different forms of corporate governance on the structure and nature of stakeholder relationships within organizations and the consequent impact on human resource management (HRM) policy and outcomes. The analysis shows that while performance advantages can be derived from commitment-based HRM systems, a corporate governance regime that privileges remote stakeholders may operate as a constraint on such systems. The empirical analysis is based on the UK Workplace Employee Relations Survey (WERS98).

1. Introduction What is regarded as best practice in work organization has evolved from managerial control over the conception and execution of work epitomized by Taylorism to the involvement of workers in the planning, organizing and undertaking of production associated with modern human resource management (HRM) (Guest 1987; Legge 1995; Walton 1985; Wilkinson 2003). However, in the Anglo-American system, there has been no supporting development in corporate governance to this shifting of responsibility for production to the shop oor. In quoted companies, the primacy of shareholder interests in law and in practice has been reinforced by theories of shareholder value, which give the stock market pride of place in policing business efciency. In the public sector, scal stringency has had an analogous effect by giving the Treasury unprecedented control over the running of public sector organizations. The importance of these developments lies in the fact that by

Sue Konzelmann is at Birkbeck, University of London and at the Centre for Business Research in the University of Cambridge. Neil Conway and Linda Trenberth are at Birkbeck, University of London. Frank Wilkinson is at Cambridge University and at Birkbeck, University of London.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

542

British Journal of Industrial Relations

designating dominant stakeholders and prioritizing their interests, corporate governance importantly inuences the structure and nature of stakeholder relationships and the credibility of commitments that stakeholders make to one another. This, in turn, affects their willingness to fully participate in productive activities. This paper investigates the interrelationship between corporate governance, HRM practices and HRM outcomes at the level of the rm. The inuence of corporate governance on the design and implementation of the HRM practices within an organization derives from the requirements of the dominant stakeholder and the contribution HRM might make to meet these requirements. Corporate governance also has consequences for the effective translation of HRM practices into HRM outcomes because by prioritizing stakeholder interests, it determines the degree of organizational commitment that stakeholders are willing and able to extend to one another. To examine these interactions, we conduct a comparative analysis of companies operating under different forms of corporate governance. These include the following: public sector organizations, in which the government is the dominant stakeholder; private sector public limited companies (PLCs), in which shareholders are the dominant stakeholder; owner-managed companies, in which the owner-manager is the dominant stakeholder; and other forms of private sector rms, in which stakeholder control is more diffused. Section 2 considers the interrelationship between corporate governance and HRM within corporate productive systems. From this, a framework is developed for analysing this interaction and how alternative forms of corporate governance inuence the credibility of commitments that stakeholders are able to make to one another. Section 3 explores these relationships and their effects empirically, using the 1998 Workplace Employee Relations Survey (WERS98). Section 4 concludes.

2. Corporate governance and HRM Corporate governance regulates the ownership and control of organizations (Berle and Means 1932). It sets the legal terms and conditions for the allocation of property rights among stakeholders, structuring their relationships and inuencing their incentives, and hence, willingness to work together. Cooperation is important because of its role in making effective the diffusion of responsibility for production, process improvement and innovation. It also serves to secure the commitment of stakeholders to the objectives of the organization, and to make available the full benets of their skills, knowledge and experience. Ideally, this is a central purpose of HRM and its role in enhancing organizational performance (Baker 1999; Black and Lynch 1997; Huselid 1995; Ichniowski et al. 1996; Konzelmann 2003; Pfeffer 1998). The form corporate governance takes therefore impacts the effectiveness of HRM practices.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management Corporate Governance, Stakeholder Relations and HRM

543

Corporate governance legally structures stakeholder relations and prioritizes the interests that corporate managers are required to serve. In considering the effects of corporate governance on stakeholder relations and HRM policy and outcomes, it is useful to distinguish between internal and external stakeholders, and the extent of their involvement in the organizations productive activities. Managers and workers directly employed by the organization and fully engaged in its productive activities, for example, are completely internal, while agency and other forms of temporary workers, suppliers, customers, communities, shareholders and the government are to varying degrees external stakeholders. While all rms have both internal and external stakeholders, with differential levels of inuence, by assigning dominance to particular groups, corporate governance has an impact on the organizational commitment each might make. Thus, the signicance of the distinction between internal and external stakeholders lies in the level and continuity of the commitment each needs to make to ensure the success of the organization and the importance to the stakeholders well-being associated with the reciprocation of that commitment by the organization. For example, there is a high level of mutual dependency between the organization and its directly employed managers and workers; and the success of the organization depends very much on the commitment of these internal stakeholders while they, in turn, rely on the organization for their present and future income and their job prospects. By contrast, at the other extreme, shareholders (as stakeholders) have no direct role to play in the productive activities of the organization. Moreover, their income security is unlikely to be exclusively or even mainly dependent on any single organization. Therefore, the degree of mutual dependency and commitment required between the organization as a producer and its shareholders can be expected to be low. However, this is not the end of the story. The degree of commitment that organizations are required to make to each stakeholder group is not only determined by mutual dependence in production. In a highly competitive product market (or in one with highly concentrated buyer power), for example, a supplier might be required to prioritize the interests of customers to the neglect of those of stakeholders it depends upon in production. More directly related to the purpose of this paper, the form of corporate governance may require managers to rank the priorities of the organizations stakeholders in ways that could compromise their commitment to the workforce, and in so doing, to undermine the interests of the organization as producer. It follows from this that the further the dominant stakeholder is from direct and continuous involvement in production, the more difcult it may become for internal stakeholders to implement and maintain mutually acceptable strategies aimed at long-term production effectiveness. In organizations with a dominant external stakeholder, such as shareholders or the state, the requirement that management prioritizes such interests may reduce their

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

544

British Journal of Industrial Relations

ability to give the necessary weight to the interests of internal stakeholders; and this will make it more difcult to secure their commitment to organizational objectives. The demands of the dominant stakeholder could therefore impact on HRM practices developed and implemented by internal stakeholders, and on the achievement of their objectives. In the public sector, for example, the objectives of government, the dominant stakeholder, are twofold: (a) to meet the electorates demand for high quality services, (b) at levels of tax they nd acceptable. The ability to accomplish the rst of these objectives requires the full commitment of internal stakeholders (i.e. public sector workers), but this might be impeded by the scal stringency resulting from governmental tax policy. In PLCs, the placing of shareholder interests rst may condition management to give priority to dividend pay-outs and shortterm share value appreciation, achieved by concentrating on cost cutting and labour force downsizing to the neglect of the longer-term interests of the business. By contrast, in organizations for which corporate governance designates an internal stakeholder as dominant, owner-management for example, there are likely to be fewer constraints on the ability of managers and employees to work together to secure long-term organizational viability to their mutual advantage. In these rms as well, the tendency towards small size increases the likelihood that efcient work organization will depend more on friendly relations between managers and employees and loyalty from workers (Craig et al. 1982: 7883). HRM and Organizational Strategy Advocates of HRM argue that it has become an increasingly important component of organizational strategy and that there is a growing recognition of the increasing returns to greater worker involvement in the planning and execution of work, as well as to worker self-regulation and a more democratic style of management (Appelbaum and Batt 1994; Blyton and Turnbull 1992; Guest 1987; Wilkinson 2003). Broadly speaking, the purpose of HRM is to foster a pre-emptive rather than reactive approach to operational efciency, quality control and innovation by shifting responsibility and accountability for decision making towards the shop oor. The adoption of HRM therefore testies to a shift in labour management practice from coercion to the attempted production of self-regulated individuals (Hollway 1991: 20). However, other researchers operating within a critical paradigm offer a powerful and wide-ranging critique of HRM (see Legge 1995; Keenoy 1999; Willmott 1993). Within the normative paradigm, the idea that an organizations human resources are of critical importance, and that the skills, knowledge and involvement of employees have strategic importance has led to the emergence of strategic HRM (SHRM) (Dyer and Kochan 1995; Lundy 1994; Schuler et al. 1993; Truss and Grattan 1994). This strategic orientation has important implications for the interrelationship between HRM and governance. An important focus of SHRM is the notion of exibility and t. Flexibility

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

545

reects an organizations capability of recognizing and adapting to changes in environmental pressures, opportunities and constraints (Snell et al. 1996). The concept of t rests on the idea that particular types of business strategy are best supported by specic bundles of HRM practices and policies generating desired employee attitudes and behaviour (Capelli and Singh 1992). Fit has both horizontal and vertical dimensions. Horizontal t requires consistency within bundles of HRM practices (Baird and Meshoulam 1988), and vertical t involves aligning HRM practices with the rms strategic business approach (Schuler and Jackson 1987). The expectation of a direct link between an organizations strategic business approach and corporate governance opens up the possibility of a link between strategic HRM and the form taken by corporate governance. In discussing types of HRM practices, it is useful to distinguish between what have been described as hard and soft dimensions, both of which may be important in integrating HRM into business strategy but which differ in the contribution that employees are expected to make to the achievement of business objectives (Storey 2002). The focus of hard HRM is on maximizing the economic return from labour resources. Its key objectives include continuous improvement in quality and performance, just-in-time inventory systems and statistical process control designed to iron out variation in quality, create consistency in meeting standards, locate inventory savings and eliminate waste. From the hard HRM perspective, labour is primarily a factor of production, the effective management of which requires emphasis on the quantitative, calculative and business strategic aspects of managing the headcount resource in as rational a way as for any other economic factor (Storey 1987: 6). By contrast, soft HRM views workers as valued assets and a source of competitive advantage through their commitment, adaptability and high quality of skills performance (Legge 1995: 66). With a greater emphasis on human relations, the objective of soft HRM is to release the untapped reserves of human resourcefulness by increasing employee commitment, participation and involvement (Blyton and Turnbull 1992: 4). Employees are viewed as active inputs into the productive process, capable of development, involvement and informed choice. Communication, motivation, leadership and a shared or mutual vision of the organization and its objectives are therefore encouraged in order to develop and strengthen commitment (Beer and Spector 1985). It is important to note that hard and soft models of HRM are not necessarily mutually exclusive; rather, they form parts of a whole HRM strategy that may be more heavily inuenced by aspects of one or the other. Yet regardless of the relative emphasis on hard and soft approaches, models of HRM assign central importance to commitment to the objectives of the organization (Guest 1987; Legge 1995; Walton 1985), where commitment implies identication with the goals and values of the organization, a desire to belong to the organization and a willingness to display effort on behalf of the organization (Mowday et al. 1982). Organizational commitment is important because it is seen to motivate workers to work harder and go

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

546

British Journal of Industrial Relations

beyond contract; to self-monitor and control, eliminating the need for supervisory and inspection personnel; to persist with the organization, thereby increasing the returns to investments in selection, training and development; and to avoid collective activities that might lower the quality and quantity of individual contributions to the organization (Guest 1987). Nevertheless, there are clear distinctions to be made between hard and soft HRM in managementworker relations. Hard HRM has a broader engineering base, a clear afnity with Taylors vision of scientic management and thus requires more explicit top-down management. By contrast, soft HRM has rmer roots in human relations, requires greater involvement of workers, emphasizes voluntarism and democratic forms of government and depends therefore more on mutual trust than managerial authority for its successful implementation (see Appelbaum and Batt 1994, especially pp. 12345). However, critics argue that soft HRM is a subtler version of hard HRM that essentially shares its aim of increasing management control and efciency. They argue, further, that soft HRM is potentially more insidious than hard HRM because it tries to achieve control through colonizing employees consciousness (Legge 1995; Willmott 1993). Notwithstanding these differences, the strategic objective of HRM is seen to be the need to create a satisfying work environment while at the same time rewarding the development of skills and creativity, thereby gaining competitive advantage (Handel and Gittleman 2004). In this respect, Appelbaum and Batt (1994) stressed the importance of

four features of a rms human resources practices and industrial relations system [which] affect how participatory arrangements inuence performance: whether the gains from improvements are shared with the workers, whether the workers have employment security, whether the rm has adopted measures to build group cohesiveness, and whether there are guaranteed individual rights for workers. (144)

The insistence here is that the benets from HRM need to accrue to both the organization and the individuals working for it. There is evidence, however, that these conditions are not generally met and that although high performance work systems may benet the organization and its shareholders, these gains are not necessarily extended to employees. In fact, many studies show that these work systems disadvantage employees because performance gains from new management practices [give] rise instead [to] work intensication, ofoading of task controls, and increased job strain (Ramsay et al. 2000: 501; see also Burchell et al. 1999). In this, corporate governance may be a key contributing factor. Corporate Governance and HRM Insight into the interrelationship between systems of governance and work organization can be found in the works of Gospel and Pendleton (2003, 2005) and Jacoby (2005). Gospel and Pendleton (2003), for example, argue that governance and related incentive structures in the Anglo-American

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

547

shareholder-based model encourage managers to readily downsize their workforces and to avoid investments, such as training, that have uncertain returns. They also found that while institutional investors tend to prioritize short-term prots, shareholder value and liquidity, family owners are more likely to consider long-term organizational viability, control and private benets to be the more important objectives. Organizations key equity holders thus play an important role in shaping HR practices because of the pressure that different classes of investors are able to exert on management and the inuence that this will have on the work systems they adopt. Studies of workplace organization in the secondary sector, generally composed of small rms the vast majority of which are owner-managed (Cosh and Hughes 2003) nd that friendly relations between managers and employees and a reliance on employee co-operation and loyalty are a means by which efcient work organization is achieved (Craig et al. 1982, 1984). Craig et al. (1982, 1984), for example, found that few small rms had specialized, full-time supervisory staff and that management usually organized the work process, while also being responsible for marketing, delivery of goods and other functions, which took them away from the workplace. A foreman or a senior worker was often left in charge; but a production worker doubling as foreman was not well-placed to exercise continual direct supervision over the labour force. Thus, the evidence showed that among these rms, output and quality depended upon individual efciency, requiring workers to accept relatively high degrees of responsibility; it also showed that close supervision was rare. In general, small rms tended to rely upon a mixture of paternalistic employment systems and a strong orientation to work on the part of the employees, often supported by the ready dismissal of mists (Craig et al. 1982: 7883; 1984). National systems of nance and corporate governance have also been shown to inuence labour management because of the differences in the level of importance that they assign to worker interests, time frames, strategy types, nancial measures of performance, the use of market-based instruments to secure commitment and the extent of employer co-ordination (Gospel and Pendleton 2003; Jacoby 2005). In liberal market systems epitomized by the USA and UK, for example, managers are required to pursue shareholder interests above those of labour, which often requires them to break the psychological contract with labour in the interest of short-term shareholder value (Burchell et al. 1999). Hall and Soskice (2001: 16), too, suggest that intensied pressure from investors has shifted the balance against labour in managerial decision making because of weaker statutory protection for labour. Nevertheless, the extent to which shareholders pursue short-term nancial interests to the detriment of long-term organizational interests varies even within the liberal market-based systems. For example, some large listed rms in the UK (such as pharmaceutical companies) have stable and active relationships with investors and at the same time are committed to employment security, career opportunities and human capital development. Thus, the

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

548

British Journal of Industrial Relations

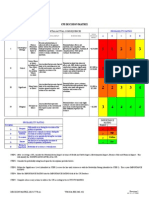

extent and ways by which managerial discretion is exercised is inuenced by characteristics of shareholders, managers and the sectors in which they operate (Gospel and Pendleton 2003; Deakin et al. 2002). Table 1 outlines the characteristics of the four types of corporate governance, which form the basis for our analysis of the WERS98 data set. In public sector organizations, the government is the dominant stakeholder, dependent on taxes for funding; and the interests of customers or taxpayers are prioritized in regulations requiring the delivery of high quality products and services at as low a scal cost as possible. Public sector service provision is labour intensive and employees are at the front line of service delivery. Consequently, HRM and the close working together of managers, employees, suppliers and customers are the key to delivering the potentially competing objectives of high quality and low cost. We would therefore expect to see high levels of work pressure and extensive use of HRM, both in its hard and soft forms, in public sector organizations. In PLCs, the shareholder is the dominant stakeholder, whose continued loyalty to the rm is dependent on the delivery of shareholder value, usually in the short term. Shareholders commitment tends to be more to the income generated by the shares they hold rather than to the organization, so that their interests are detached from those of employees. This forms the basis for potentially conictual stakeholder relations because of the priority managers are legally required to afford shareholder risks, undermining their commitment to employees a dilemma epitomized by the popularity of a reduction in workforce headcount to the stock market. In this context, human resources are likely to be viewed as a cost to be minimized or the source of more effective exploitation. We would therefore expect HRM to be biased towards hard practices and to target the delivery of short-term nancial returns.

TABLE 1 Corporate Governance and Human Resources Type of organization Public sector organization Dominant stakeholder Government (external) Primary organizational objective High quality/low price products for customers produced at low cost for customers/taxpayers Shareholder value (emphasis on short-term) Long-term economic performance and institutional viability (protability and sustainability) Long-term economic performance and institutional viability (protability and sustainability) Dominant view of human resources Central to accomplishment of potentially competing quality, price and cost objectives Cost to be minimized Resource to be exploited Central to accomplishment of long-term performance objectives and institutional viability Central to accomplishment of long-term performance objectives and institutional viability

Private sector: PLC Private sector: other

Shareholder (external) Depends on corporate form (internal) Ownermanager (internal)

Ownermanaged rm

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

549

In owner-managed rms, owner-managers are the dominant stakeholders and their interests are prioritized. The predominance of insider stakeholder interests is also likely to be a feature of other forms of private sector organization, including private limited companies, partnerships, trusts and charities, co-operatives, mutuals and friendly societies, and other non-PLC private sector organizations. Consequently, in owner-managed and private sector other organizations identied in WERS98, we would expect a greater prioritization of internal stakeholder interests leading to longer-term organizational objectives. It is also likely that relations among internal stakeholders will be closer and more amicable, with greater informality in HRM practices, particularly given the relatively small size of these types of organization. Nevertheless, long-term economic organizational performance is expected to depend on HRM, made more effective by the absence of a dominant external stakeholder.1 Operationalizing the Analysis of Corporate Governance and HRM Many attempts have been made to identify HRM best practices, high commitment work practices or high performance work systems (Becker and Gerhart 1996; Wall and Wood 2005). And although there is a substantial body of research that identies a positive link between HRM and organizational performance (see, for example, Appelbaum et al. 2000; Huselid 1995; Ichniowski et al. 1996; Jayaram et al. 1999; Koch and McGrath 1996; Vandenberg et al. 1999), there is little understanding of the mechanisms through which HRM practices inuence effectiveness (Delery 1998: 289). While efforts have been made to identify these mechanisms, most have been based on the common sense notion that improving the way people work and are managed leads to improved performance (Truss 2001). The difculty, however, is that organizational performance is much more complex and depends upon a wide range of external factors, including corporate governance, that are not directly inuenced by HRM. While HRM might have an inuence on organizational performance within a given environment, it is only one of an array of variables impacting performance; and HRM, itself, is likely to be inuenced by these other variables. Corporate governance, for example, prioritizes the objectives managers are required to pursue with consequent impacts on HRM. However, managers are also required to take account of other external constraints such as changes in demand, the nature and degree of competition and technologies; and each of these affects performance but all are outside the direct inuence of HRM. While HRM may accommodate itself to these constraints, inuencing performance through its impact on productivity, production costs and quality, innovation and the ability to respond to changes in environmental conditions and requirements, the impact of HRM tends to be indirect, complicated and highly context dependent. In a ercely competitive environment, for example, HRM may be a determining factor in the organizations ability to stay in business; so its effect may not show up in high prots or rapid growth. Under

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

550

British Journal of Industrial Relations

more benign competitive conditions, however, effective HRM might reveal itself in super-normal rates of prots and rm expansion. In essence, two stages of performance can be identied: (a) the ability of the HRM system to deliver the HRM outcomes it is designed to achieve and (b) the ability of the organization to successfully accommodate itself to the requirements of the external environment in which it operates. The focus of the present study is on the rst stage of performance, as constrained by corporate governance. Various authors suggest that the strategic HRM model contains strong economic and calculative considerations together with a more humanistic orientation designed to promote mutual goals, mutual inuence, respect, rewards and responsibility (Gooderham et al. 1999). However, different forms of corporate governance and strategy are likely to be associated with different emphases in HR practices (Gospel and Pendleton 2003). In the present study, the choices of HRM practices and outcomes to be included in the analysis were somewhat constrained by the data set and the information contained in the WERS98 survey. Nevertheless, from the items available, we decided to include those HRM practices reecting both collaborative or soft HRM and calculative or hard HRM that have been shown to contribute to organizational performance and may be related to corporate governance. These include information sharing and consultation (Delery and Doty 1996; Huselid 1995; Pfeffer 1998), incentive systems (Arthur 1994; Huselid 1995; MacDufe 1995; Pfeffer 1998), training (Arthur 1994; Huselid 1995; MacDufe 1995; Pfeffer 1998), organization of work including job design and working in teams (Arthur 1994; MacDufe 1995; Pfeffer 1998). Items relating to managerial commitment to HRM are also included because it is hypothesized that the level of managerial commitment is inuenced by form of corporate governance and therefore the extent to which they prioritize the interests of their employees. The effectiveness of HRM practices in achieving the HRM outcomes, which they are designed to deliver, is an important intermediary link between HRM practices and organizational performance. Examining this, Guest (1997) proposed that high performance at the individual level which ostensibly leads to improved performance at the organizational level depends upon high motivation, possession of the necessary skills and abilities, and an appropriate role and understanding of that role. Following this logic, the HRM outcome variables included in our study include, from the managers perspective, (a) employee commitment to organizational values and (b) the quality of labour-management relations; and from the employees perspective, (a) work pressure, (b) job satisfaction, (c) organizational commitment and (d) the quality of labour-management relations. We would expect that better HRM outcomes, such as lower levels of work pressure, higher levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment, and a high quality of labourmanagement relations, will contribute to better individual and, hence, organizational performance. We also argue that these HRM outcomes can be related to the form taken by corporate governance. Because managerial

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

551

co-ordination and control mechanisms are likely to vary with workforce numbers, irrespective of the form of governance, we control for organization size (indicated by total number of employees in the UK) in the statistical analysis below. The model in Figure 1 provides a guide to the empirical analysis of the interrelationship between corporate governance, HRM practices and HRM outcomes within organizations. In our analysis, these relationships are examined at the level of the establishment, with the terminology rm, organization and enterprise being used interchangeably with reference to establishments in each of the corporate governance sectors in the study. As discussed previously, WERS98 provides information on HRM practices including consultation, training, incentive systems, work organization and

FIGURE 1 Corporate Governance and HRM System Approaches and Outcomes.

Corporate Governance

Organizational Objectives and Strategies

HRM Practices

Consultation

Production processes Social processes Information ows Employment Future plans

Training

Training of management and employees Technical aspects of work Social aspects of work Information ows

Managerial commitment to HRM Organization of work

Job control, multi-skilling teamworking Degree of autonomy in: Production organization Social organization

Incentive systems

Payment systems Employment security

HRM Outcomes

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

552

British Journal of Industrial Relations

managerial commitment to HRM. These are represented in the analysis by composite variables constructed from variables taken from the WERS98 data set (see Appendix, Table A). Consultation, for example, is composed of consultation (both horizontal and vertical) regarding production and social processes, information ows within the organization on employment issues, future plans and the implications of proposed changes. Training encompasses training for management and employees in the technical and social aspects of work as well as information ows within the organization. Incentive systems encompass practices relating to compensation and employment security. The organization of work concerns employee autonomy, discretion and control over their work, job exibility and teamworking. Managerial commitment to HRM is represented by such variables as the training of managers in people management skills, appointment of an employee relations representative to the Board of Directors, and existence of a strategic plan covering employee development. HRM outcomes include employee commitment to the organization, quality of the relationship between management and employees, employee attitudes about work pressure and job satisfaction. In the following section, these relationships are examined more closely using the data contained in the WERS98 survey.

3. Data analysis The WERS98 survey is based on a sample of more than 3,000 workplaces in Britain. It involved interviews with managers having responsibility for employee relations issues, interviews with worker representatives, and surveys completed by more than 30,000 employees. As a whole, the survey represents approximately 75 per cent of all employees in the UK. For purposes of the analysis here, public sector, PLC, owner-managed companies and other types of private sector rms are compared, together representing 2,189 workplaces (682 in the public sector, 829 PLCs, 208 owner-managed rms and 470 other private sector rms). Of these, the majority (81 per cent) were in the nonproduction sector, with a higher concentration of small rms located in the owner-managed and private sector other categories. Appendix Table A presents in detail the variables used in the empirical analysis below, showing how composite variables were constructed from management and employee responses to WERS98 questions, how these were coded for purposes of creating the composite variables and how the items were aggregated. Signicance levels are based on a one-way analysis of variance comparing the corporate governance forms for each of the HRM practice and HRM outcome variables. The statistical analysis and all later regression analyses are conducted at the level of the workplace (N = 2,189 for analyses drawing solely on manager responses; N = 1,720 when drawing on manager responses and employee responses). Employee responses are aggregated to the level of the workplace by taking the arithmetic mean from employees surveyed at that workplace. On average, 16 employees were

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

553

surveyed from each workplace. Appendix Table B presents the correlations between the study variables. To investigate more closely the separate effects of organizational size and corporate governance form on HRM practices and HRM outcomes, we conducted two sets of regression analysis. In the rst model, organization size and corporate governance form are used to predict HRM practices and outcomes. In the second model, HRM practices are added to organization size and corporate governance form to predict HRM outcomes. In each regression, organization size is introduced in step 1 as a control variable and the corporate governance forms are entered in step 2. In the second regression model, HRM practices are entered in step 3. The results are summarized in Tables 24. The four category variables of corporate governance (Public sector, PLC, Owner-managed and Private sector other) were converted into dummy variables, and the omitted dummy variable was Private sector other companies. Therefore, in the regression analyses, the effects of other corporate governance types are relative to Private sector other. Size, Corporate Governance, and HRM Practices and Outcomes Based on the responses of managers and employees, organization size is signicantly and positively related to many of the HRM practices; but it is signicantly and inversely related to employees inuence over work, and, to a lesser extent, to their perception of the quality of consultation and personal policy (see Table 2). With respect to HRM outcomes, from the managers perspective, size is signicant and inversely related to employee commitment to the values of the organization (see Table 3); from the viewpoint of employees, size is signicant and inversely related to job satisfaction, employee commitment to the organizations values and the quality of employeemanagement relations. Considering the impact of corporate governance form on HRM practices (see Table 2), based on managers responses, the strongest model is that for managerial commitment to HRM, where organization size and corporate governance together explain 22 per cent of the variation in commitment. In this, being a PLC is positively related to managerial commitment (beta = 0.16) while being in the public sector (beta = 0.15) or owner-managed (beta = 0.10) are negatively related. In other words, and recalling that these types of corporate governance are relative to the omitted dummy variable of private sector other, PLCs are more likely to exhibit evidence of managerial commitment to HRM than other private sector, public sector and owner-managed rms; and public sector and owner-managed rms exhibit signicantly lower managerial commitment to HRM than other private sector rms. The second largest R2 is for consultation, where 12 per cent of the variation in consultation can be explained by size and corporate governance form. In this model, being in the public sector is positively related to consultation (beta = 0.14) while being owner-managed is negatively related (beta = 0.14). This suggests that public sector rms have well-developed consultation systems while

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

554

British Journal of Industrial Relations

TABLE 2 Corporate Governance and Organization Size as Predictors of HRM Practices: Management and Employee Questionnaires

HRM practices Consultation

Management questionnaire Incentives Managerial commitment to HRM Training Teamwork; worker exibility, discretion and control 0.03 0.02 0.14*** 0.06* 0.03***

Organization size 0.20*** Corporate governance form PLC 0.00 Public sector 0.14*** Owner-managed 0.14*** Adjusted R2 0.12***

Standardized beta coefcients 0.26*** 0.32*** 0.09*** 0.09*** 0.17*** 0.01 0.11*** 0.16*** 0.15*** 0.10*** 0.22*** 0.06* 0.15*** 0.07** 0.05***

Employee questionnaire Consultation over job prospects, training and pay Employee views sought on workplace future, stafng, work practices and terms and conditions Quality of consultation and personnel policy Training Inuence over work

Organization size 0.13*** Corporate governance form PLC 0.10*** Public sector 0.10*** Owner-managed 0.12*** Adjusted R2 0.08***

Standardized beta coefcients 0.01 0.05* 0.01 0.11*** 0.00 0.01*** 0.03 0.08* 0.04 0.01***

0.14*** 0.09** 0.23*** 0.14*** 0.13***

0.19*** 0.00 0.01 0.00 0.03***

Note: The remaining category of corporate governance Private sector other is the omitted dummy variable. *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

owner-managed enterprises tend not to, regardless of size; it also indicates that while PLCs and other private sector rms (the omitted dummy variable) have less developed consultation systems than public sector organizations, they have more developed systems than do owner-managed enterprises. The third strongest model is that predicting incentive systems, where 11 per cent of the variation in incentive systems can be explained by size and corporate governance form. In this, being a PLC is positively related to the existence of a system of individual incentives (beta = 0.09) while being in the public sector is negatively related (beta = 0.17). PLCs are more likely to exhibit evidence of incentive systems than other private sector (the omitted dummy variable) and public sector rms; and public sector rms have signicantly fewer individual incentive systems compared with other private sector rms. The incentive systems of owner-managed rms do not differ signicantly from

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

TABLE 3 Corporate Governance and Organization Size as Predictors of HRM Outcomes: Management and Employee Questionnaires HRM outcomes Management questionnaire Employee commitment to organizations values Organization size Corporate governance form PLC Public sector Owner-managed Adjusted R2

555

Quality of employeemanagement relations

Standardized beta coefcients 0.11*** 0.05 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.01*** Employee questionnaire 0.01 0.04 0.05* 0.01***

Work pressure Organization size 0.01 Corporate governance form PLC 0.01 Public sector 0.25*** Owner-managed 0.08** Adjusted R2 0.07***

Job satisfaction

Organizational commitment

Quality of employeemanagement relations 0.11*** 0.03 0.01 0.01 0.01***

Standardized beta coefcients 0.17*** 0.18*** 0.04 0.02 0.02 0.03*** 0.01 0.10*** 0.04 0.03***

The remaining category of corporate governance Private sector other is the omitted dummy variable. *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

other private sector rms. The other models explain less than 5 per cent of the variation in the dependent variable, so they are not elaborated here. From the employees perspective, the lower explanatory power of the regression models in terms of the adjusted R2 suggests that size and corporate governance form are less important predictors of HRM practices and outcomes than they are when the managers perspective is considered. We therefore restrict our discussion here to cases where the independent variables explain more than 5 per cent of the variation in the dependent variable. As evident in Table 2, from the employees perspective, organization size and corporate governance explain 13 per cent of the variation in training, where the public sector exhibits higher levels of training (beta = 0.23) when compared with the other forms of corporate governance, and owner-managed enterprises exhibit lower levels of training (beta = 0.14). Organization size and corporate governance explain 8 per cent of the variation in consultation over job prospects, training and pay, where the public sector and ownermanaged enterprises have lower levels of consultation in these areas than other private sector rms (beta = 0.10 and 0.012, respectively), while PLCs have signicantly higher levels than other private sector rms (beta = 0.10).

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

556

British Journal of Industrial Relations

Turning to the relationships between corporate governance and HRM outcomes in Table 3, from a management perspective, corporate governance has negligible associations with employee commitment to the organizations values or the quality of employeemanagement relations. From the employees perspective, however, the results are more signicant in that corporate governance and organizational size together explain 7 per cent of the variance in work pressure, with public sector employees reporting the highest levels of work pressure (beta = 0.25) and owner-managed rms reporting the lowest (beta = 0.08). The form taken by corporate governance explains only a small amount of the variance (less than 5 per cent) in the remaining HRM outcomes of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and the perceived state of employment relations. The only signicant nding here is that public sector employees report signicantly higher levels of commitment to the organizations values (beta = 0.10) than employees working in other rms. HRM Practices: A Predictor of HRM Outcomes To investigate the degree to which HRM outcomes can be explained by HRM practices, we turn to the second set of regressions, where organization size was entered in step 1, corporate governance form in step 2 and HRM practices in step 3. The results from the managers perspective and those from the employees perspective are summarized in Table 4. Of these models, the strongest are those from the employees perspective, with those based on managers responses accounting for less than 15 per cent of the variation in HRM outcomes. Considering HRM outcomes from the managers perspective rst, managers report higher levels of employee commitment and a better quality of employment relations in rms where employees rate highly the quality of consultation and personnel policy (beta = 0.23 and 0.33, respectively) and where managers report high levels of consultation (beta = 0.13 and 0.09, respectively), teamwork, worker exibility, discretion and control (beta = 0.11 and 0.09, respectively). The remaining signicant nding is that the quality of employment relations is negatively related to consultation over job prospects, training and pay (beta = 0.13). Considering HRM outcomes from the employees perspective, the regressions predicting the quality of employeemanagement relations, job satisfaction and organizational commitment were all very strong. In these, respectively, 73, 58 and 45 per cent of the variation in the HRM outcomes under consideration can be explained by including the independent variables of size, corporate governance form and HRM practices in the model. In each, by far the strongest of the independent variables is the quality of consultation and personnel policy (beta = 0.84 for the quality of employeemanagement relations, beta = 0.62 for job satisfaction, beta = 0.57 for employee commitment to organizations values), followed by the level of inuence employees feel they have over their jobs (beta = 0.09 for the quality of employee management relations, beta = 0.30 for job satisfaction, beta = 0.19 for

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

TABLE 4 HRM Practices as a Predictor of HRM Outcomes: Management and Employee Perspectives on HRM Outcomes Dependent variables from managements perspective Employee commitment to organizations values 0.14*** 0.00 0.01 0.00 0.13*** 0.06* 0.05 0.03 0.11*** 0.06* 0.02 0.23*** 0.05 0.00 0.13*** 0.14*** 0.33*** 0.01 0.06** 0.13*** 0.05 0.13*** 0.04 0.11*** 0.05 0.04 0.12*** 0.09*** 0.01 0.04 0.05 0.09*** 0.06* 0.01 0.01 0.03 0.08*** 0.01 0.01 0.05** 0.01 0.00 0.08*** 0.01 0.62*** 0.02 0.30*** 0.58*** 0.09** 0.00 0.07** 0.24*** 0.01 0.05 0.06* 0.00 0.01 0.06* Standardized beta coefcients 0.05 0.05** 0.12** 0.03 0.01 0.02 0.04* 0.02 0.03 0.04* 0.03 0.02 0.03 0.57*** 0.05* 0.19*** 0.45*** Quality of employeemanagement relations Work pressure Job satisfaction Employee commitment to organizations values Dependent variables from employees perspectives Quality of employeemanagement relations 0.03 0.07** 0.00 0.03 0.04** 0.01 0.04** 0.01 0.00 0.01 0.04** 0.84*** 0.02 0.09*** 0.73***

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

HRM outcomes

Organization size Corporate governance form Public sector PLC Owner-managed Management responses Consultation Incentive systems Managerial commitment to HRM Training Teamwork, worker exibility, discretion and control Employee responses Consultation over job prospects, training and pay Employee views sought on workplace future, stafng, work practices, terms and conditions Quality of consultation and personnel policy Training Inuence over work

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

Adjusted R2

Note: The remaining category of corporate governance Private sector other is the omitted dummy variable. *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

557

558

British Journal of Industrial Relations

employee commitment to organizations values). The other signicant nding is that job satisfaction was negatively related to employees views about consultation about job prospects, training and pay (beta = 0.08). Also apparent in Table 4 is the signicant positive relationship between being in the public sector and employees reporting high levels of work pressure (beta = 0.24), low levels of job satisfaction (beta = 0.06) and a low quality of employeemanagement relations (beta = 0.07). The relationship between corporate governance forms and HRM outcomes are not signicant for the other three sectors. These ndings in general suggest that the more effective employees feel management to be and the greater their control over the pace and content of their work, the better will be the relationship between managers and employees, the greater will be employees job satisfaction and the more committed they will be to the values of their organizations. The responses of both managers and employees with respect to HRM practices indicate a positive relationship between work pressure and consultation (beta = 0.06 for managers and beta = 0.13 for employees). Work pressure is also positively associated with managers reporting higher levels of teamwork, worker exibility, discretion and control (beta = 0.08) and employees reporting a low quality of consultation and personnel policy (beta = 0.11). This suggests that consultation, multi-skilling and teamworking, and a low quality of consultation and personnel policy generate increased work pressures for employees.

4. Summary and conclusions To its advocates, the role of HRM is to diffuse responsibility for production, process improvement and innovation to the shop oor and in so doing to enhance organizational performance. For this purpose, employee cooperation is important both to secure their commitment to the objectives of the organization and to make available the full benets of employees skills, knowledge and experience. However, the securing of employee co-operation may depend upon the degree to which their managers are able to prioritize employee interests; and this may depend upon the form of corporate governance under which they operate and hence the priority managers are required to give to the interests of other stakeholders. The suggestion is that organizations, which have a dominant external stakeholder, such as PLCs and public sector organizations, may be constrained in their ability to implement and maintain commitment-based HRM systems. This is because the meeting of remote stakeholders demands may prevent managers from making credible commitments to employees, which in turn inhibits their ability to secure the full co-operation from their workforce that is required for effective HRM. To explore these ideas, we used the WERS98 data set to compare rms operating under alternative forms of corporate governance, including PLCs, public sector organizations, owner-managed and other types of private sector rms. Composite variables for HRM practices and HRM outcomes were

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

559

constructed from both managers and employees questionnaires; and in a three-step model, size, corporate governance and the HRM practices were systematically examined as potential determinants of HRM outcomes. When controlled for size, corporate governance has the most far-reaching impact on HRM in the public sector. Here, both managers and employees perceive the quality of employeemanagement relationships to be poor; and workers report high levels of work pressure and low levels of job satisfaction. Nevertheless, public sector workers have a relatively high level of commitment to the organization. These ndings can be explained in part by the governments squeeze on the public sector, which has intensied work, lowered job satisfaction and worsened employeemanagement relations; however, it has not had such an adverse effect on the public service ethos as to undermine employees commitment to the organization. This ability to exploit the vocational commitment of public sector workers helps to explain why services have held up despite evidence that public sector organizations have been starved of resources by government policy (albeit at no small cost to the providers in the form of high work pressure and low job satisfaction) (Burchell et al. 1999).2 When HRM practices are considered, consultation and teamwork, worker exibility, discretion and control positively contribute to managements assessment of employee commitment to organizational values and the quality of employeemanagement relations, although individual incentive systems have a negative effect. Responses from employees indicate that consultation over job prospects, training and pay, and the quality of consultation and personnel policies are positively related to their managers evaluation of employee commitment to the organizations values. However, while employees views on the quality of consultation are directly related to their managers assessment of the quality of employeemanagement relations, their views on consultation over job prospects, training and pay and inuence over work are inversely related. The WERS98 data set thus clearly shows that the effect of many of the standard HRM practices is to increase work pressure, lower job satisfaction and worsen relationships between workers and their managers. However, the most important determinants of employees job satisfaction, commitment to the organization and high quality relationship with management are the quality of consultation and personnel policy and the inuence employees feel that they have over their work. In general, the managers responses reveal a tendency for HRM outcomes to worsen as organizational size increases, a conclusion supported by employees, especially with respect to job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Thus, the smaller the size of the organization, the greater the ability to deliver the outcomes expected from the effective use of HRM. However, Table 2 shows that the smaller the organization, the less its managers are committed to HRM and the less likely they are to adopt formal HRM practices. A possible explanation for this apparent paradox is that the stated objectives of HRM high levels of employee autonomy, selfsupervision and responsibility for production become increasingly a

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

560

British Journal of Industrial Relations

functional necessity for the successful running of the organization, the smaller it is and the less specialized are its managers. This suggests that HRM is a strategy adopted by large rms to recapture some of the advantages of reliance on their workforce that were lost by the adoption of Taylorist work organization. However, Table 4 suggests that the success of this strategy in capturing the support of their employees depends less on specic HRM practices than on the quality of consultation and personnel policy, which managers and employees both agree increases employee commitment to the values of the organization and the quality of employeemanagement relations. Further, for workers, the better the quality of consultation and personnel policy, the lower the work pressure to which they are subject and the higher their job satisfaction. Thus, the analysis of WERS98 strongly suggests that what secures positive HRM outcomes are, for workers, the quality of consultation and personnel policy (i.e. how good managers are at keeping workers up-to-date about change, providing opportunities to comment on proposed changes, responding to employees suggestions, dealing with employees work problems, and treating employees fairly) and, to a lesser extent, employee inuence over work (i.e. how much workers have inuence over tasks, pace of work and how work is done). There can be little doubt that in securing these objectives corporate governance has an important part to play, as does the size of operating establishments. Final version accepted on 6 May 2006.

Notes

1. This does not rule out the possibility that non-PLC private sector rms and especially smaller rms may be subject to particular pressure from dominant suppliers or customers, the interests of which their managers might need to prioritize. 2. Bearing in mind that when the WERS98 survey was conducted, the Labour government was adhering to the previous Tory administration tax and spending plans.

References

Appelbaum, E. and Batt, R. (1994). The New American Workplace: Transforming Work Systems in the United States. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press. , Bailey, T., Berg, P. and Kallberg, A. L. (2000). Manufacturing Advantage; Why High Performance Work Systems Pay Off. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Arthur, J. (1994). Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 37 (3): 67087. Baird, L. and Meshoulam, I. (1988). Managing the two ts of strategic human resource management. Academy of Management Review, 13 (1): 11628.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

561

Baker, T. (1999). Doing Well by Doing Good: The Bottom Line on Workplace Practices. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. Becker, B. and Gerhart, B. (1996). The impact of human resource management on performance: progress and prospects. Academy of Management Journal, 39 (4): 779801. Beer, M. and Spector, B. (1985). Corporate wide transformations in human resource management. In R. Walton and P. Lawrence (eds.), Human Resource Management: Trends and Challenges. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, pp. 21953. Berle, A. and Means, G. (1932). The Modern Corporation and Private Property. New York: Macmillan. Black, S. and Lynch, L. (1997). How to Compete: The Impact of Workplace Practices and Information Technology on Productivity. Working Paper no. 6120, NBER. Blyton, P. and Turnbull, P. (1992). Debates, dilemmas and contradictions. In P. Blyton and P. Turnbull (eds.), Reassessing Human Resource Management. London: Sage Publications, pp. 215. Burchell, B., Day, D. Hudson, M., Ladipo, D., Mankelow, R., Nolan, J., Reed, H., Wichert, I. and Wilkinson, F. (1999). Job Insecurity and Work Intensication. York: York Publishing Services. Capelli, P. and Singh, H. (1992). Integrating strategic human resources and strategic management. In D. Lewin, O. Mitchell and P. Scherer (eds.), Research Frontiers in Industrial Relations and Human Resources. Madison, WI: Industrial Relations Research Association, pp. 16592. Cosh, A. and Hughes, A. (2003). Enterprise Challenge. Cambridge: Cambridge Centre for Business Research. Craig, C., Garnsey, E. and Rubery, J. (1984). Payment Structures and Smaller Firms: Womens Employment in Segmented Labour Markets. Research Paper No. 48, Department of Employment, London. , Rubery, J., Tarling, R. and Wilkinson, F. (1982). Labour Market Structure, Industrial Organisation and Low Pay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Deakin, S., Hobbs, R., Konzelmann, S. and Wilkinson, F. (2002). Partnership, ownership and control: the impact of corporate governance on employment relations. Employee Relations, 24 (3): 33552. Delery, J. E. (1998). Issues of t in strategic human resource management: implications for research. Human Resource Management Review, 8 (3): 289310. and Doty, H. (1996). Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management. Academy of Management Journal, 39 (4): 80235. Dyer, L. and Kochan, T. (1995). Is there a new HRM? Contemporary evidence and future directions. In B. Downie, P. Kumar and M. L. Coates (eds.), Managing Human Resources in the 1990s and Beyond: Is the Workplace Being Transformed? Kingston, ON: Industrial Relations Centre Press, Queens University. Gooderham, P., Nordhaug, O. and Ringdal, K. (1999). Institutional and rational determinants of organizational practices: human resource management in European rms. Administrative Quarterly, 44: 50731. Gospel, H. and Pendleton, A. (2003). Finance, corporate governance and the management of labour. A conceptual and comparative analysis. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 41 (3): 55782. and (2005). Corporate Governance and Labour Management: An International Comparison. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Guest, D. (1987). Human resource management and industrial relations. Journal of Management Studies, 24 (5): 50321.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

562

British Journal of Industrial Relations

(1997). Human resource management and performance: a review and research agenda. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 8 (3): 26376. Hall, P. and Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Handel, M. and Gittleman, M. (2004). Is there a Wage Payoff to Innovative Work Practices? Industrial Relations, 43(1): 6797. Hollway, W. (1991). Work Psychology and Work Organization. London: Sage. Huselid, M. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate nancial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38 (3): 63572. Ichniowski, C., Kochan, T., Levine, D., Olson, C. and Straus, G. (1996). What works at work: overview and assessment. Industrial Relations, 35 (3): 299333. Jacoby, S. (2005). The Embedded Corporation: Corporate Governance and Employment Relations in Japan and the United States. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Jayaram, J., Droge, G. and Vickery, S. K. (1999). The impact of human resource management practices on manufacturing performance. Journal of Operations Management, 18: 120. Keenoy, T. (1999). HRM as hologram: a polemic. Journal of Management Studies, 36 (1): 123. Koch, M. J. and McGrath, R. G. (1996). Improving labour productivity: human resource policies do matter. Strategic Management Journal, 17: 33554. Konzelmann, S. (2003). Markets, corporate governance and creative work systems: the case of ferodyn. The Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 14 (2): 13958. Legge, K. (1995). Human Resource Management: Rhetorics and Realities. London: Macmillan Publishers. Lundy, O. (1994). From personnel management to strategic human resource management. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 5 (3): 687720. MacDufe, J. (1995). Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: organizational logic and exible production systems in the world auto industry. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48: 197221. Mowday, R., Porter, L. and Steers, R. (1982). EmployeeOrganization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism and Turnover. London: Academic Press. Pfeffer, J. (1998). The Human Equation: Building Prots by Putting People First. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Ramsay, H., Scholarios, D. and Harley, B. (2000). Employees and high-performance work systems: testing inside the black box. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 38(4): 50131. Schuler, R. and Jackson, S. (1987). Linking competitive strategies with human resource management practices. Academy of Management Executive, 1 (3): 20719. , Dowling, P. and De Cieri, H. (1993). An integrated framework of strategic international human resource management. Journal of Management, 19 (2): 41959. Snell, S. A., Youndt, M. A. and Wright, P. M. (1996). Establishing a framework for research in strategic human resource management: merging resource theory and organizational learning. In G. R. Ferris and K. M. Rowland (eds.), Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, Vol. 14. New York: JAI Press, pp. 6190. Storey, J. (1987). Developments in the Management of Human Resources: An Interim Report. Warwick Papers in Industrial Relations No. 17, University of Warwick IRRU School of Industrial and Business Studies.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

563

(2002). Human Resource Management: A Critical Text. London: Thomson Learning. Truss, C. (2001). Complexities and controversies in linking HRM with organizational outcomes. Journal of Management Studies, 38 (8): 112149. and Grattan, L. (1994). Strategic human resource management: a conceptual approach. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 5 (3): 66386. Vandenberg, R., Richardson, H. A. and Eastman, L. J. (1999). The impact of high involvement work processes on organizational effectiveness. Groups and Organization Management, 24: 30039. Wall, T. D. and Wood, S. J. (2005). The romance of human resource management and business performance and the case for big science. Human Relations, 58 (94): 42962. Walton, R. (1985). Towards a strategy of eliciting employee commitment based on policies of mutuality. In R. Walton and P. Lawrence (eds.), Human Resource Management: Trends and Challenges. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, pp. 3565. Wilkinson, F. (2003). Productive systems and the structuring role of economic and social theories. In B. Burchell, S. Deakin, J. Michie and J. Rubery (eds.), Systems of Production: Markets, Organizations and Performance. London: Routledge, pp. 1039. Willmott, H. (1993). Strength is ignorance; slavery is freedom: managing culture in modern organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 30 (4): 51552.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Appendix

564

TABLE A Summary of HRM Practices and HRM Outcomes Variables Meaning Scale Sig. level b

Summary variable

British Journal of Industrial Relations

0.000

1 = agree; 0 = DK, disagreea 1 = agree; 0 = DK, disagreea 1 = agree; 0 = DK, disagreea 1 = disagree; 0 = DK, agreea 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = agree; 0 = DK, disagreea 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = 60% +; 0 = less than 60% 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = 60% +; 0 = less than 60% 1 = 5 days or more; 0 = less than 5 days 1 = yes; 0 = no

0.000

0.000

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

HRM practices Management questionnaire Consultation Count across 10 items: 1. Management seek employee views about job specications 2. Management discuss implications of change with employees 3. Those at top make decisions 4. Decisions made without consultation with employees 5. System of briengs? 6. Is brieng generally for the whole workplace? 7. Consultation committees? 8. Wide range of issues concerning employees discussed by committees 9. Quality circles? 10. Other ways management communicates with employees Incentive systems Count across 5 items: 1. Employees led to expect job security 2. Employees get PRP or bonuses 3. Employees get individual or group performance schemes 4. Most non-managerial staff receiving performance related pay 5. Guaranteed job security for certain groups of employees Managerial Count across 3 items: commitment 1. Per cent of supervisors trained in people management skills to HRM 2. Employee relations rep on Board of Directors? 3. If yes to BSTRATEG, does the formal strategic plan cover employee development? Training Count across 3 items: 1. Per cent employees with off-the-job training 2. Time spent on off-the-job training for employees 3. Did training cover teamworking, communication, problem solving, quality control procedures?

0.000

Indicates that a longer interval scale (such as a 5 or 7-point Likert scale) was dichotomized. Signicance level based on one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing corporate governance forms for each HRM system, HRM system performance and organizational performance variable.

Summary variable 1 = 60% +; 0 = less than 60% 1 = Some or a lot; 0 = little or none 1 = Some or a lot; 0 = little or none 1 = 60% +; 0 = less than 60% 1 = yes; 0 = no 0.000

Meaning

Scale

Sig. level b

Teamwork, worker exibility, discretion and control

Count across 5 items: 1. Per cent of employees trained to do jobs other than their own 2. Do employees have discretion in work? 3. Do employees have control over pace of work? 4. Per cent of employees in formal teams 5. Teamwork involves 3 or more of co-operation, control over leadership, control over work, and responsibility for products and services

0.000

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no 1 = yes; 0 = no All items measured on a 4-point scale where 1 = never, 2 = hardly ever, 3 = sometimes, 4 = frequently.

0.000

Employee questionnaire Consultation over Count across 4 items: consultation with line manager about: job prospects, 1. job progress training and pay 2. promotion chances 3. training needs 4. pay Employee views Arithmetic mean across 5 items: frequency managers ask for employee views about: sought on 1. future plans for workplace workplace future, 2. stafng issues stafng, work 3. changes to work practices practices, terms 4. pay issues and conditions 5. health and safety at work Quality of Arithmetic mean across 5 items: How good are managers at: consultation and 1. keeping workers up to date about change personnel policy 2. providing opportunities to comment on proposed changes 3. responding to employees suggestions 4. dealing with employees work problems 5. treating employees fairly Training Single item: Off-the-job training in past 12 months

All items measured on a 5-point scale where 1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = neither good nor poor, 4 = good, 5 = very good

0.001

0.000 0.002

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

Inuence over work

Arithmetic mean across 3 items: How much inuence over: 1. tasks 2. pace of work 3. how work is done

All items measured on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 = none to 6 = 10 days or more All items measured on a 4-point scale where 1 = none, 2 = a little, 3 = some, 4 = a lot.

565

Indicates that a longer interval scale (such as a 5 or 7-point Likert scale) was dichotomized. Signicance level based on one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing corporate governance forms for each HRM system, HRM system performance and organizational performance variable.

566

Table A (contd ) Meaning Scale Sig. level b

Summary variable

0.092 0.001

HRM outcomes Management questionnaire Employee Single item: employee commitment to the values of the organization commitment to orgns values Quality of employee- Single item: relationship between management and employees mgmt relations

5-point scale where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree 5-point scale where 1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = neither good nor poor, 4 = good, 5 = very good

Employee questionnaire Work pressure Arithmetic mean across 2 items: 1. Job requires to work very hard 2. Pressures to get job done on time

0.000

British Journal of Industrial Relations

Job satisfaction

Items measured on a 5-point scale where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree Items measured on a 5-point scale where 5 = very satised, 4 = satised, 3 = neither, 2 = dissatised, 1 = very dissatised

0.002

Organizational commitment

Quality of employeemgmt relations

Arithmetic mean across 4 items: Satisfaction: 1. inuence over job 2. pay 3. sense of achievement 4. respect from line managers Arithmetic mean across 3 items: 1. Share values of the organization 2. Loyalty to organization 3. Pride in working here Single item: relationship between management and employees

0.000

Items measured on a 5-point scale where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree 5-point scale where 1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = neither good nor poor, 4 = good, 5 = very good

0.011

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006.

Indicates that a longer interval scale (such as a 5 or 7-point Likert scale) was dichotomized. Signicance level based on one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing corporate governance forms for each HRM system, HRM system performance and organizational performance variable.

TABLE B Zero-order Correlations between Study Variables

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

0.52 0.25 0.26 0.38 0.25 0.07 0.23 0.15 0.10 0.15 0.33 0.30 0.27 0.26 0.12 0.06 0.24 0.13 0.25 0.09 0.07 0.21 0.03 0.07 0.37 0.01 0.13 0.00 0.09 0.00 0.21 0.13 0.17 0.07 0.12 0.05 0.08 0.27 0.07 0.11 0.07 0.25 0.34 0.27 0.01 0.10 0.13 0.30 0.15 0.09 0.04 0.11 0.23 0.57 0.22 0.15 0.13 0.16 0.33 0.18 0.31 0.08 0.17 0.01 0.23 0.23 0.24 0.23 0.28 0.01 0.69 0.65 0.84 0.09 0.21 0.11 0.18 0.12 0.10 0.39 0.17 0.06 0.05 0.28 0.02 0.04 0.00 0.02 0.22 0.00 0.02 0.14 0.08 0.16 0.02 0.06 0.28 0.01 0.17 0.00 0.07 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.01 0.08 0.17 0.03 0.03 0.26 0.07 0.13 0.05 0.00 0.06 0.12 0.03 0.02 0.19 0.08 0.10 0.28 0.25 0.37 0.16 0.08

22 0.19

0.02 0.24 0.35 0.03 0.04

0.21 0.17 0.15 0.15 0.15

0.05

0.02

0.02

0.05

Blackwell Publishing Ltd/London School of Economics 2006. 0.26 0.19 0.07 0.16 0.14 0.08 0.08 0.00 0.07 0.04 0.23 0.09 0.03 0.08 0.04 0.00 0.03 0.04 0.23 0.26 0.06 0.48 0.37 0.33 0.05 0.13 0.07 0.74 0.69 0.64

0.22

0.10

0.05

0.10

0.07

0.09

0.04 0.06 0.10 0.08 0.10

0.24 0.03 0.26 0.01 0.08

1. PLC 2. Public sector 3. Owner-managed 4. Organization size Management responses* 5. Consultation 6. Incentive systems 7. Managerial commitment to HRM 8. Training 9. Teamwork, worker exibility, discretion and control 10. Employee commitment to organizations values 11. Quality of employee-management relations Employee responses** 12. Consultation over job prospects, training and pay 13. Employees views sought on workplace future, stafng, work practices, terms and conditions 14. Quality of consultation and personnel policy 15. Training 16. Inuence over work 17. Work pressure 18. Job satisfaction 19. Employee commitment to organizations values 20. Quality of employee-management relations

Corporate Governance and Human Resource Management

0.06

0.01

* Rows 1 to 11 reported by managers, N ranges from 2187 to 2192. Correlation coefcients exceeding 0.05, 0.06 and 0.07 are signicant at the 5%, 1% and 0.1% levels, respectively. ** Rows 12 to 20 reported by employees, N ranges from 1779 to 1783. Correlation coefcients exceeding 0.05, 0.06 and 0.08 are signicant at the 5%, 1% and 0.1% levels, respectively.

567

You might also like

- The Collapse of The Soviet Union and Its Impact OnDocument6 pagesThe Collapse of The Soviet Union and Its Impact Onxaxif8265No ratings yet

- The Determinants of Capital Structure: Analysis of Non Financial Firms Listed in Karachi Stock Exchange in PakistanDocument29 pagesThe Determinants of Capital Structure: Analysis of Non Financial Firms Listed in Karachi Stock Exchange in Pakistanxaxif8265No ratings yet

- Impact of Labeling and Packaging On Buying Behavior of Young Consumers WithDocument8 pagesImpact of Labeling and Packaging On Buying Behavior of Young Consumers Withxaxif8265No ratings yet

- The Impact of Point of Purchase Advertising On Consumer Buying BehaviourDocument5 pagesThe Impact of Point of Purchase Advertising On Consumer Buying Behaviourxaxif8265No ratings yet

- Joseph E. Stinlitz Free Fall)Document16 pagesJoseph E. Stinlitz Free Fall)xaxif8265No ratings yet

- Impact of Advertisement On Children Behavior: Evidence From PakistanDocument8 pagesImpact of Advertisement On Children Behavior: Evidence From PakistanJasdeep KaurNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of The Service Quality Using Gap Analysis A Study Conducted atDocument8 pagesAn Assessment of The Service Quality Using Gap Analysis A Study Conducted atxaxif8265No ratings yet

- Study of Teachers' Opinion Regarding Techniques ToDocument7 pagesStudy of Teachers' Opinion Regarding Techniques Toxaxif8265No ratings yet

- Impact of Brand Related Attributes On Purchase Intention ofDocument7 pagesImpact of Brand Related Attributes On Purchase Intention ofxaxif8265No ratings yet

- How To Review The Financial StatementDocument3 pagesHow To Review The Financial Statementxaxif8265No ratings yet

- Is Broad Size An in Dependance Corporate Governace MachnisimDocument30 pagesIs Broad Size An in Dependance Corporate Governace Machnisimxaxif8265No ratings yet

- A Resource-Based View of The FirmDocument11 pagesA Resource-Based View of The Firmxaxif8265No ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of Public and Private SchoolsDocument10 pagesA Comparative Study of Public and Private Schoolsxaxif8265100% (2)

- Investigating Relationships Between Relationship Quality, Customer Loyalty and CooperationDocument19 pagesInvestigating Relationships Between Relationship Quality, Customer Loyalty and Cooperationxaxif8265No ratings yet

- How Downsizing Affects The Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction of Layoff SurvivorsDocument7 pagesHow Downsizing Affects The Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction of Layoff Survivorsxaxif8265100% (1)

- Graphical Representation of Statistical DataDocument56 pagesGraphical Representation of Statistical Dataxaxif8265100% (5)

- Is The Resource Based View A Useful Prespective For Strategic Management? YESDocument16 pagesIs The Resource Based View A Useful Prespective For Strategic Management? YESxaxif8265No ratings yet