Professional Documents

Culture Documents

LGC

Uploaded by

Aicka Bustamante Singson0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views30 pagesPetitioners seek review on certiorari to nullify and set aside two issuances of the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City. Respondent Bayan Telecommunications, Inc. Is a legislative franchise holder under Rep. Act No. 3259. Section 232 of the Code grants local government units within the Metro Manila Area the power to levy tax on real properties.

Original Description:

Original Title

lgc

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPetitioners seek review on certiorari to nullify and set aside two issuances of the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City. Respondent Bayan Telecommunications, Inc. Is a legislative franchise holder under Rep. Act No. 3259. Section 232 of the Code grants local government units within the Metro Manila Area the power to levy tax on real properties.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views30 pagesLGC

Uploaded by

Aicka Bustamante SingsonPetitioners seek review on certiorari to nullify and set aside two issuances of the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City. Respondent Bayan Telecommunications, Inc. Is a legislative franchise holder under Rep. Act No. 3259. Section 232 of the Code grants local government units within the Metro Manila Area the power to levy tax on real properties.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 30

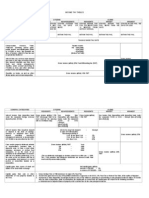

THE CTY GOVERNMENT OF QUEZON CTY, AND THE CTY

TREASURER OF QUEZON CTY, DR. VCTOR B.

ENRGA, Petitioners,

vs.

BAYAN TELECOMMUNCATONS, NC., Respondent.

D E C S O N

GARCA,

Before the Court, on pure questions of law, is this petition for review on

certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court to nullify and set aside

the following issuances of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Quezon

City, Branch 227, in its Civil Case No. Q-02-47292, to wit:

1) Decision

1

dated June 6, 2003, declaring respondent Bayan

Telecommunications, nc. exempt from real estate taxation on its real

properties located in Quezon City; and

2) Order

2

dated December 30, 2003, denying petitioners' motion for

reconsideration.

The facts:

Respondent Bayan Telecommunications, nc.

3

(Bayantel) is a

legislative franchise holder under Republic Act (Rep. Act) No. 3259

4

to

establish and operate radio stations for domestic telecommunications,

radiophone, broadcasting and telecasting.

Of relevance to this controversy is the tax provision of Rep. Act No.

3259, embodied in Section 14 thereof, which reads:

SECTON 14. (a) The grantee shall be liable to pay the same taxes on

its real estate, buildings and personal property, exclusive of the

franchise, as other persons or corporations are now or hereafter may

be required by law to pay. (b) The grantee shall further pay to the

Treasurer of the Philippines each year, within ten days after the audit

and approval of the accounts as prescribed in this Act, one and one-

half per centum of all gross receipts from the business transacted

under this franchise by the said grantee (Emphasis supplied).

On January 1, 1992, Rep. Act No. 7160, otherwise known as the

"Local Government Code of 1991" (LGC), took effect. Section 232 of

the Code grants local government units within the Metro Manila Area

the power to levy tax on real properties, thus:

SEC. 232. Power to Levy Real Property Tax. A province or city or a

municipality within the Metropolitan Manila Area may levy an annual ad

valorem tax on real property such as land, building, machinery and

other improvements not hereinafter specifically exempted.

Complementing the aforequoted provision is the second paragraph of

Section 234 of the same Code which withdrew any exemption from

realty tax heretofore granted to or enjoyed by all persons, natural or

juridical, to wit:

SEC. 234 - Exemptions from Real Property Tax. The following are

exempted from payment of the real property tax:

xxx xxx xxx

Except as provided herein, any exemption from payment of real

property tax previously granted to, or enjoyed by, all persons, whether

natural or juridical, including government-owned-or-controlled

corporations is hereby withdrawn upon effectivity of this Code

(Emphasis supplied).

On July 20, 1992, barely few months after the LGC took effect,

Congress enacted Rep. Act No. 7633, amending Bayantel's original

franchise. The amendatory law (Rep. Act No. 7633) contained the

following tax provision:

SEC. 11. The grantee, its successors or assigns shall be liable to pay

the same taxes on their real estate, buildings and personal property,

exclusive of this franchise, as other persons or corporations are now or

hereafter may be required by law to pay. n addition thereto, the

grantee, its successors or assigns shall pay a franchise tax equivalent

to three percent (3%) of all gross receipts of the telephone or other

telecommunications businesses transacted under this franchise by the

grantee, its successors or assigns and the said percentage shall be in

lieu of all taxes on this franchise or earnings thereof. Provided, That

the grantee, its successors or assigns shall continue to be liable for

income taxes payable under Title of the National nternal Revenue

Code .. xxx. [Emphasis supplied]

t is undisputed that within the territorial boundary of Quezon City,

Bayantel owned several real properties on which it maintained various

telecommunications facilities. These real properties, as hereunder

described, are covered by the following tax declarations:

(a) Tax Declaration Nos. D-096-04071, D-096-04074, D-096-04072

and D-096-04073 pertaining to Bayantel's Head Office and Operations

Center in Roosevelt St., San Francisco del Monte, Quezon City

allegedly the nerve center of petitioner's telecommunications franchise

operations, said Operation Center housing mainly petitioner's Network

Operations Group and switching, transmission and related equipment;

(b) Tax Declaration Nos. D-124-01013, D-124-00939, D-124-00920

and D-124-00941 covering Bayantel's land, building and equipment in

Maginhawa St., Barangay East Teacher's Village, Quezon City which

houses telecommunications facilities; and

(c) Tax Declaration Nos. D-011-10809, D-011-10810, D-011-10811,

and D-011-11540 referring to Bayantel's Exchange Center located in

Proj. 8, Brgy. Bahay Toro, Tandang Sora, Quezon City which houses

the Network Operations Group and cover switching, transmission and

other related equipment.

n 1993, the government of Quezon City, pursuant to the taxing power

vested on local government units by Section 5, Article X of the 1987

Constitution, infra, in relation to Section 232 of the LGC, supra,

enacted City Ordinance No. SP-91, S-93, otherwise known as the

Quezon City Revenue Code (QCRC),

5

imposing, under Section 5

thereof, a real property tax on all real properties in Quezon City, and,

reiterating in its Section 6, the withdrawal of exemption from real

property tax under Section 234 of the LGC, supra. Furthermore, much

like the LGC, the QCRC, under its Section 230, withdrew tax

exemption privileges in general, as follows:

SEC. 230. Withdrawal of Tax Exemption Privileges. Unless otherwise

provided in this Code, tax exemptions or incentives granted to, or

presently enjoyed by all persons, whether natural or juridical, including

government owned or controlled corporations, except local water

districts, cooperatives duly registered under RA 6938, non-stock and

non-profit hospitals and educational institutions, business enterprises

certified by the Board of nvestments (BO) as pioneer or non-pioneer

for a period of six (6) and four (4) years, respectively, . are hereby

withdrawn effective upon approval of this Code (Emphasis supplied).

Conformably with the City's Revenue Code, new tax declarations for

Bayantel's real properties in Quezon City were issued by the City

Assessor and were received by Bayantel on August 13, 1998, except

one (Tax Declaration No. 124-01013) which was received on July 14,

1999.

Meanwhile, on March 16, 1995, Rep. Act No. 7925,

6

otherwise known

as the "Public Telecommunications Policy Act of the Philippines,"

envisaged to level the playing field among telecommunications

companies, took effect. Section 23 of the Act provides:

SEC. 23. Equality of Treatment in the Telecommunications ndustry.

Any advantage, favor, privilege, exemption, or immunity granted under

existing franchises, or may hereafter be granted, shall ipso facto

become part of previously granted telecommunications franchises and

shall be accorded immediately and unconditionally to the grantees of

such franchises: Provided, however, That the foregoing shall neither

apply to nor affect provisions of telecommunications franchises

concerning territory covered by the franchise, the life span of the

franchise, or the type of service authorized by the franchise.

On January 7, 1999, Bayantel wrote the office of the City Assessor

seeking the exclusion of its real properties in the city from the roll of

taxable real properties. With its request having been denied, Bayantel

interposed an appeal with the Local Board of Assessment Appeals

(LBAA). And, evidently on its firm belief of its exempt status, Bayantel

did not pay the real property taxes assessed against it by the Quezon

City government.

On account thereof, the Quezon City Treasurer sent out notices of

delinquency for the total amount ofP43,878,208.18, followed by the

issuance of several warrants of levy against Bayantel's properties

preparatory to their sale at a public auction set on July 30, 2002.

Threatened with the imminent loss of its properties, Bayantel

immediately withdrew its appeal with the LBAA and instead filed with

the RTC of Quezon City a petition for prohibition with an urgent

application for a temporary restraining order (TRO) and/or writ of

preliminary injunction, thereat docketed as Civil Case No. Q-02-47292,

which was raffled to Branch 227 of the court.

On July 29, 2002, or in the eve of the public auction scheduled the

following day, the lower court issued a TRO, followed, after due

hearing, by a writ of preliminary injunction via its order of August 20,

2002.

And, having heard the parties on the merits, the same court came out

with its challenged Decision of June 6, 2003, the dispositive portion of

which reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, pursuant to the enabling

franchise under Section 11 of Republic Act No. 7633, the real estate

properties and buildings of petitioner [now, respondent Bayantel] which

have been admitted to be used in the operation of petitioner's franchise

described in the following tax declarations are hereby DECLARED

exempt from real estate taxation:

(1) Tax Declaration No. D-096-04071

(2) Tax Declaration No. D-096-04074

(3) Tax Declaration No. D-124-01013

(4) Tax Declaration No. D-011-10810

(5) Tax Declaration No. D-011-10811

(6) Tax Declaration No. D-011-10809

(7) Tax Declaration No. D-124-00941

(8) Tax Declaration No. D-124-00940

(9) Tax Declaration No. D-124-00939

(10) Tax Declaration No. D-096-04072

(11) Tax Declaration No. D-096-04073

(12) Tax Declaration No. D-011-11540

The preliminary prohibitory injunction issued in the August 20, 2002

Order of this Court is hereby made permanent. Since this is a

resolution of a purely legal issue, there is no pronouncement as to

costs.

SO ORDERED.

Their motion for reconsideration having been denied by the court in its

Order dated December 30, 2003, petitioners elevated the case directly

to this Court on pure questions of law, ascribing to the lower court the

following errors:

. []n declaring the real properties of respondent exempt from real

property taxes notwithstanding the fact that the tax exemption granted

to Bayantel in its original franchise had been withdrawn by the [LGC]

and that the said exemption was not restored by the enactment of RA

7633.

. [n] declaring the real properties of respondent exempt from real

property taxes notwithstanding the enactment of the [QCRC] which

withdrew the tax exemption which may have been granted by RA

7633.

. [n] declaring the real properties of respondent exempt from real

property taxes notwithstanding the vague and ambiguous grant of tax

exemption provided under Section 11 of RA 7633.

V. [n] declaring the real properties of respondent exempt from real

property taxes notwithstanding the fact that [it] had failed to exhaust

administrative remedies in its claim for real property tax exemption.

(Words in bracket added.)

As we see it, the errors assigned may ultimately be reduced to two (2)

basic issues, namely:

1. Whether or not Bayantel's real properties in Quezon City are exempt

from real property taxes under its legislative franchise; and

2. Whether or not Bayantel is required to exhaust administrative

remedies before seeking judicial relief with the trial court.

We shall first address the second issue, the same being procedural in

nature.

Petitioners argue that Bayantel had failed to avail itself of the

administrative remedies provided for under the LGC, adding that the

trial court erred in giving due course to Bayantel's petition for

prohibition. To petitioners, the appeal mechanics under the LGC

constitute Bayantel's plain and speedy remedy in this case.

The Court does not agree.

Petitions for prohibition are governed by the following provision of Rule

65 of the Rules of Court:

SEC. 2. Petition for prohibition. When the proceedings of any

tribunal, . are without or in excess of its or his jurisdiction, or with

grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction,

and there is no appeal or any other plain, speedy, and adequate

remedy in the ordinary course of law, a person aggrieved thereby may

file a verified petition in the proper court, alleging the facts with

certainty and praying that judgment be rendered commanding the

respondent to desist from further proceedings in the action or matter

specified therein, or otherwise, granting such incidental reliefs as law

and justice may require.

With the reality that Bayantel's real properties were already levied

upon on account of its nonpayment of real estate taxes thereon, the

Court agrees with Bayantel that an appeal to the LBAA is not a speedy

and adequate remedy within the context of the aforequoted Section 2

of Rule 65. This is not to mention of the auction sale of said properties

already scheduled on July 30, 2002.

Moreover, one of the recognized exceptions to the exhaustion- of-

administrative remedies rule is when, as here, only legal issues are to

be resolved. n fact, the Court, cognizant of the nature of the questions

presently involved, gave due course to the instant petition. As the

Court has said in Ty vs. Trampe:

7

xxx. Although as a rule, administrative remedies must first be

exhausted before resort to judicial action can prosper, there is a well-

settled exception in cases where the controversy does not involve

questions of fact but only of law. xxx.

Lest it be overlooked, an appeal to the LBAA, to be properly

considered, required prior payment under protest of the amount

of P43,878,208.18, a figure which, in the light of the then prevailing

Asian financial crisis, may have been difficult to raise up. Given this

reality, an appeal to the LBAA may not be considered as a plain,

speedy and adequate remedy. t is thus understandable why Bayantel

opted to withdraw its earlier appeal with the LBAA and, instead, filed its

petition for prohibition with urgent application for injunctive relief in Civil

Case No. Q-02-47292. The remedy availed of by Bayantel under

Section 2, Rule 65 of the Rules of Court must be upheld.

This brings the Court to the more weighty question of whether or not

Bayantel's real properties in Quezon City are, under its franchise,

exempt from real property tax.

The lower court resolved the issue in the affirmative, basically owing to

the phrase "exclusive of this franchise" found in Section 11 of

Bayantel's amended franchise, Rep. Act No. 7633. To petitioners,

however, the language of Section 11 of Rep. Act No. 7633 is neither

clear nor unequivocal. The elaborate and extensive discussion devoted

by the trial court on the meaning and import of said phrase, they add,

suggests as much. t is petitioners' thesis that Bayantel was in no time

given any express exemption from the payment of real property tax

under its amendatory franchise.

There seems to be no issue as to Bayantel's exemption from real

estate taxes by virtue of the term "exclusive of the franchise" qualifying

the phrase "same taxes on its real estate, buildings and personal

property," found in Section 14, supra, of its franchise, Rep. Act No.

3259, as originally granted.

The legislative intent expressed in the phrase "exclusive of this

franchise" cannot be construed other than distinguishing between two

(2) sets of properties, be they real or personal, owned by the

franchisee, namely, (a) those actually, directly and exclusively used in

its radio or telecommunications business, and (b) those properties

which are not so used. t is worthy to note that the properties subject of

the present controversy are only those which are admittedly falling

under the first category.

To the mind of the Court, Section 14 of Rep. Act No. 3259 effectively

works to grant or delegate to local governments of Congress' inherent

power to tax the franchisee's properties belonging to the second group

of properties indicated above, that is, all properties which, "exclusive of

this franchise," are not actually and directly used in the pursuit of its

franchise. As may be recalled, the taxing power of local governments

under both the 1935 and the 1973 Constitutions solely depended upon

an enabling law. Absent such enabling law, local government units

were without authority to impose and collect taxes on real properties

within their respective territorial jurisdictions. While Section 14 of Rep.

Act No. 3259 may be validly viewed as an implied delegation of power

to tax, the delegation under that provision, as couched, is limited to

impositions over properties of the franchisee which are not actually,

directly and exclusively used in the pursuit of its franchise. Necessarily,

other properties of Bayantel directly used in the pursuit of its business

are beyond the pale of the delegated taxing power of local

governments. n a very real sense, therefore, real properties of

Bayantel, save those exclusive of its franchise, are subject to realty

taxes. Ultimately, therefore, the inevitable result was that all realties

which are actually, directly and exclusively used in the operation of its

franchise are "exempted" from any property tax.

Bayantel's franchise being national in character, the "exemption" thus

granted under Section 14 of Rep. Act No. 3259 applies to all its real or

personal properties found anywhere within the Philippine archipelago.

However, with the LGC's taking effect on January 1, 1992, Bayantel's

"exemption" from real estate taxes for properties of whatever kind

located within the Metro Manila area was, by force of Section 234 of

the Code, supra, expressly withdrawn. But, not long thereafter,

however, or on July 20, 1992, Congress passed Rep. Act No. 7633

amending Bayantel's original franchise. Worthy of note is that Section

11 of Rep. Act No. 7633 is a virtual reenacment of the tax provision,

i.e., Section 14, supra, of Bayantel's original franchise under Rep. Act

No. 3259. Stated otherwise, Section 14 of Rep. Act No. 3259 which

was deemed impliedly repealed by Section 234 of the LGC was

expressly revived under Section 14 of Rep. Act No. 7633. n concrete

terms, the realty tax exemption heretofore enjoyed by Bayantel under

its original franchise, but subsequently withdrawn by force of Section

234 of the LGC, has been restored by Section 14 of Rep. Act No.

7633.

The Court has taken stock of the fact that by virtue of Section 5, Article

X of the 1987 Constitution,

8

local governments are empowered to levy

taxes. And pursuant to this constitutional empowerment, juxtaposed

with Section 232

9

of the LGC, the Quezon City government enacted in

1993 its local Revenue Code, imposing real property tax on all real

properties found within its territorial jurisdiction. And as earlier stated,

the City's Revenue Code, just like the LGC, expressly withdrew, under

Section 230 thereof, supra, all tax exemption privileges in general.

This thus raises the question of whether or not the City's Revenue

Code pursuant to which the city treasurer of Quezon City levied real

property taxes against Bayantel's real properties located within the City

effectively withdrew the tax exemption enjoyed by Bayantel under its

franchise, as amended.

Bayantel answers the poser in the negative arguing that once again it

is only "liable to pay the same taxes, as any other persons or

corporations on all its real or personal properties, exclusive of its

franchise."

Bayantel's posture is well-taken. While the system of local government

taxation has changed with the onset of the 1987 Constitution, the

power of local government units to tax is still limited. As we explained

in Mactan Cebu nternational Airport Authority:

10

The power to tax is primarily vested in the Congress; however, in our

jurisdiction, it may be exercised by local legislative bodies, no longer

merely be virtue of a valid delegation as before, but pursuant to direct

authority conferred by Section 5, Article X of the Constitution. Under

the latter, the exercise of the power may be subject to such guidelines

and limitations as the Congress may provide which, however, must be

consistent with the basic policy of local autonomy. (at p. 680;

Emphasis supplied.)

Clearly then, while a new slant on the subject of local taxation now

prevails in the sense that the former doctrine of local government units'

delegated power to tax had been effectively modified with Article X,

Section 5 of the 1987 Constitution now in place, .the basic doctrine on

local taxation remains essentially the same. For as the Court stressed

in Mactan, "the power to tax is [still] primarily vested in the Congress."

This new perspective is best articulated by Fr. Joaquin G. Bernas, S.J.,

himself a Commissioner of the 1986 Constitutional Commission which

crafted the 1987 Constitution, thus:

What is the effect of Section 5 on the fiscal position of municipal

corporations? Section 5 does not change the doctrine that municipal

corporations do not possess inherent powers of taxation. What it does

is to confer municipal corporations a general power to levy taxes and

otherwise create sources of revenue. They no longer have to wait for a

statutory grant of these powers. The power of the legislative authority

relative to the fiscal powers of local governments has been reduced to

the authority to impose limitations on municipal powers. Moreover,

these limitations must be "consistent with the basic policy of local

autonomy." The important legal effect of Section 5 is thus to reverse

the principle that doubts are resolved against municipal corporations.

Henceforth, in interpreting statutory provisions on municipal fiscal

powers, doubts will be resolved in favor of municipal corporations. t is

understood, however, that taxes imposed by local government must be

for a public purpose, uniform within a locality, must not be confiscatory,

and must be within the jurisdiction of the local unit to pass.

11

(Emphasis

supplied).

n net effect, the controversy presently before the Court involves, at

bottom, a clash between the inherent taxing power of the legislature,

which necessarily includes the power to exempt, and the local

government's delegated power to tax under the aegis of the 1987

Constitution.

Now to go back to the Quezon City Revenue Code which imposed real

estate taxes on all real properties within the city's territory and

removed exemptions theretofore "previously granted to, or presently

enjoyed by all persons, whether natural or juridical ..,"

12

there can

really be no dispute that the power of the Quezon City Government to

tax is limited by Section 232 of the LGC which expressly provides that

"a province or city or municipality within the Metropolitan Manila Area

may levy an annual ad valorem tax on real property such as land,

building, machinery, and other improvement not hereinafter specifically

exempted." Under this law, the Legislature highlighted its power to

thereafter exempt certain realties from the taxing power of local

government units. An interpretation denying Congress such power to

exempt would reduce the phrase "not hereinafter specifically

exempted" as a pure jargon, without meaning whatsoever. Needless to

state, such absurd situation is unacceptable.

For sure, in Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company, nc.

(PLDT) vs. City of Davao,

13

this Court has upheld the power of

Congress to grant exemptions over the power of local government

units to impose taxes. There, the Court wrote:

ndeed, the grant of taxing powers to local government units under the

Constitution and the LGC does not affect the power of Congress to

grant exemptions to certain persons, pursuant to a declared national

policy. The legal effect of the constitutional grant to local governments

simply means that in interpreting statutory provisions on municipal

taxing powers, doubts must be resolved in favor of municipal

corporations. (Emphasis supplied.)

As we see it, then, the issue in this case no longer dwells on whether

Congress has the power to exempt Bayantel's properties from realty

taxes by its enactment of Rep. Act No. 7633 which amended

Bayantel's original franchise. The more decisive question turns on

whether Congress actually did exempt Bayantel's properties at all by

virtue of Section 11 of Rep. Act No. 7633.

Admittedly, Rep. Act No. 7633 was enacted subsequent to the LGC.

Perfectly aware that the LGC has already withdrawn Bayantel's former

exemption from realty taxes, Congress opted to pass Rep. Act No.

7633 using, under Section 11 thereof, exactly the same defining

phrase "exclusive of this franchise" which was the basis for Bayantel's

exemption from realty taxes prior to the LGC. n plain language,

Section 11 of Rep. Act No. 7633 states that "the grantee, its

successors or assigns shall be liable to pay the same taxes on their

real estate, buildings and personal property, exclusive of this franchise,

as other persons or corporations are now or hereafter may be required

by law to pay." The Court views this subsequent piece of legislation as

an express and real intention on the part of Congress to once again

remove from the LGC's delegated taxing power, all of the franchisee's

(Bayantel's) properties that are actually, directly and exclusively used

in the pursuit of its franchise.

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENED.

No pronouncement as to costs.

ALTERNATVE CENTER FOR ORGANZATONAL REFORMS AND

DEVELOPMENT, NC., VS. ZAMORA

G.R. No. 144256

Subject: Public Corporation

Doctrine: Automatic release of RA

Facts:

Pres. Estrada, pursuant to Sec 22, Art V mandating the Pres to

submit to Congress a budget of expenditures within 30 days before the

opening of every regular session, submitted the National Expenditures

program for FY 2000. The President proposed an RA of

P121,778,000,000. This became RA 8760, "AN ACT

APPROPRATNG FUNDS FOR THE OPERATON OF THE

GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLC OF THE PHLPPNES FROM

JANUARY ONE TO DECEMBER THRTY-ONE, TWO THOUSAND,

AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES also known as General

Appropriations Act (GAA) for the Year 2000. t provides under the

heading "ALLOCATONS TO LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNTS that the

RA for local government units shall amount to P111,778,000,000.

n another part of the GAA, under the heading "UNPROGRAMMED

FUND, it is provided that an amount of P10,000,000,000 (P10 Billion),

apart from the P111,778,000,000 mentioned above, shall be used to

fund the RA, which amount shall be released only when the original

revenue targets submitted by the President to Congress can be

realized based on a quarterly assessment to be conducted by certain

committees which the GAA specifies, namely, the Development

Budget Coordinating Committee, the Committee on Finance of the

Senate, and the Committee on Appropriations of the House of

Representatives.

Thus, while the GAA appropriates P111,778,000,000 of RA as

Programmed Fund, it appropriates a separate amount of P10 Billion of

RA under the classification of Unprogrammed Fund, the latter amount

to be released only upon the occurrence of the condition stated in the

GAA.

On August 22, 2000, a number of NGOs and POs, along with 3

barangay officials filed with this Court the petition at bar, for Certiorari,

Prohibition and Mandamus With Application for Temporary Restraining

Order, against respondents then Executive Secretary Ronaldo

Zamora, then Secretary of the Department of Budget and Management

Benjamin Diokno, then National Treasurer Leonor Magtolis-Briones,

and the Commission on Audit, challenging the constitutionality of

provision XXXV (ALLOCATONS TO LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNTS)

referred to by petitioners as Section 1, XXXV (A), and LV

(UNPROGRAMMED FUND) Special Provisions 1 and 4 of the GAA

(the GAA provisions)

Petitioners contend that the said provisions violates the LGUs

autonomy by unlawfully reducing the RA allotted by 10B and by

withholding its release by placing the same under "Unprogrammed

funds. Although the effectivity of the Year 2000 GAA has ceased, this

Court shall nonetheless proceed to resolve the issues raised in the

present case, it being impressed with public interest. Petitioners argue

that the GAA violated the constitutional mandate of automatically

releasing the RAs when it made its release contingent on whether

revenue collections could meet the revenue targets originally submitted

by the President, rather than making the release automatic.

SSUE: WON the subject GAA violates LGUs fiscal autonomy by not

automatically releasing the whole amount of the allotted RA.

HELD:

Article X, Section 6 of the Constitution provides:

SECTON 6. Local government units shall have a just share, as

determined by law, in the national taxes which shall be automatically

released to them.

Petitioners argue that the GAA violated this constitutional mandate

when it made the release of RA contingent on whether revenue

collections could meet the revenue targets originally submitted by the

President, rather than making the release automatic. Respondents

counterargue that the above constitutional provision is addressed not

to the legislature but to the executive, hence, the same does not

prevent the legislature from imposing conditions upon the release of

the RA.

Respondents thus infer that the subject constitutional provision merely

prevents the executive branch of the government from "unilaterally

withholding the RA, but not the legislature from authorizing the

executive branch to withhold the same. n the words of respondents,

"This essentially means that the President or any member of the

Executive Department cannot unilaterally, i.e., without the backing of

statute, withhold the release of the RA.

As the Constitution lays upon the executive the duty to automatically

release the just share of local governments in the national taxes, so it

enjoins the legislature not to pass laws that might prevent the

executive from performing this duty. To hold that the executive branch

may disregard constitutional provisions which define its duties,

provided it has the backing of statute, is virtually to make the

Constitution amendable by statute a proposition which is patently

absurd. f indeed the framers intended to allow the enactment of

statutes making the release of RA conditional instead of automatic,

then Article X, Section 6 of the Constitution would have been worded

differently.

Since, under Article X, Section 6 of the Constitution, only the just share

of local governments is qualified by the words "as determined by law,

and not the release thereof, the plain implication is that Congress is not

authorized by the Constitution to hinder or impede the automatic

release of the RA.

n another case, the Court held that the only possible exception to

mandatory automatic release of the RA is, as held in Batangas:

.if the national internal revenue collections for the current fiscal year

is less than 40 percent of the collections of the preceding third fiscal

year, in which case what should be automatically released shall be a

proportionate amount of the collections for the current fiscal year. The

adjustment may even be made on a quarterly basis depending on the

actual collections of national internal revenue taxes for the quarter of

the current fiscal year.

This Court recognizes that the passage of the GAA provisions by

Congress was motivated by the laudable intent to "lower the budget

deficit in line with prudent fiscal management. The pronouncement in

Pimentel, however, must be echoed: "[T]he rule of law requires that

even the best intentions must be carried out within the parameters of

the Constitution and the law. Verily, laudable purposes must be carried

out by legal methods.

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED. XXXV and LV Special

Provisions 1 and 4 of the Year 2000 GAA are hereby declared

unconstitutional insofar as they set apart a portion of the RA, in the

amount of P10 Billion, as part of the UNPROGRAMMED FUND.

BATANGAS CATV, NC. vs. THE COURT OF APPEALS, THE

BATANGAS CTY SANGGUNANG PANLUNGSOD and BATANGAS

CTY MAYOR [G.R. No. 138810. September 29, 2004]

FACTS:

On July 28, 1986, respondent Sangguniang Panlungsod enacted

Resolution No. 210 granting petitioner a permit to construct, install, and

operate a CATV system in Batangas City. Section 8 of the Resolution

provides that petitioner is authorized to charge its subscribers the

maximum rates specified therein, "provided, however, that any

increase of rates shall be subject to the approval of the Sangguniang

Panlungsod.

Sometime in November 1993, petitioner increased its subscriber rates

from P88.00 to P180.00 per month. As a result, respondent Mayor

wrote petitioner a letter threatening to cancel its permit unless it

secures the approval of respondent Sangguniang Panlungsod,

pursuant to Resolution No. 210.

Petitioner then filed with the RTC, Branch 7, Batangas City, a petition

for injunction alleging that respondent Sangguniang Panlungsod has

no authority to regulate the subscriber rates charged by CATV

operators because under Executive Order No. 205, the National

Telecommunications Commission (NTC) has the sole authority to

regulate the CATV operation in the Philippines.

SSUE :

may a local government unit (LGU) regulate the subscriber rates

charged by CATV operators within its territorial jurisdiction?

HELD: No.

x x x

The logical conclusion, therefore, is that in light of the above laws and

E.O. No. 436, the NTC exercises regulatory power over CATV

operators to the exclusion of other bodies.

x x x

Like any other enterprise, CATV operation maybe regulated by LGUs

under the general welfare clause. This is primarily because the CATV

system commits the indiscretion of crossing public properties. (t uses

public properties in order to reach subscribers.) The physical realities

of constructing CATV system the use of public streets, rights of

ways, the founding of structures, and the parceling of large regions

allow an LGU a certain degree of regulation over CATV operators.

x x x

But, while we recognize the LGUs' power under the general welfare

clause, we cannot sustain Resolution No. 210. We are convinced that

respondents strayed from the well recognized limits of its power. The

flaws in Resolution No. 210 are: (1) it violates the mandate of existing

laws and (2) it violates the State's deregulation policy over the CATV

industry.

LGUs must recognize that technical matters concerning CATV

operation are within the exclusive regulatory power of the NTC.

LEONARDO TAN, ROBERT UY and LAMBERTO TE, petitioners,

vs SOCORRO Y. PEREA, respondent

D E C S O N

TNGA, .:

The resolution of the present petition effectively settles the

question of how many cockpits may be allowed to operate in a city or

municipality.

There are two competing values of high order that come to fore

in this casethe traditional power of the national government to enact

police power measures, on one hand, and the vague principle of local

autonomy now enshrined in the Constitution on the other. The facts are

simple, but may be best appreciated taking into account the legal

milieu which frames them.

n 1974, Presidential Decree (P.D.) No. 449, otherwise known as

the Cockfighting Law of 1974, was enacted. Section 5(b) of the Decree

provided for limits on the number of cockpits that may be established in

cities and municipalities in the following manner:

Section 5. Cockpits and Cockfighting in General.

(b) Establishment of Cockpits. Only one cockpit shall be allowed in

each city or municipality, except that in cities or municipalities with a

population of over one hundred thousand, two cockpits may be

established, maintained and operated.

With the enactment of the Local Government Code of 1991,

[1]

the

municipal sangguniang bayan were empowered, "[a]ny law to the

contrary notwithstanding, to "authorize and license the establishment,

operation and maintenance of cockpits, and regulate cockfighting and

commercial breeding of gamecocks.

[2]

n 1993, the Sangguniang Bayan of the municipality of

Daanbantayan,

[3]

Cebu Province, enacted Municipal Ordinance No. 6

(Ordinance No. 6), Series of 1993, which served as the Revised

Omnibus Ordinance prescribing and promulgating the rules and

regulations governing cockpit operations in Daanbantayan.

[4]

Section 5

thereof, relative to the number of cockpits allowed in the municipality,

stated:

Section 5. There shall be allowed to operate in the Municipality of

Daanbantayan, Province of Cebu, not more than its equal number of

cockpits based upon the population provided for in PD 449, provided

however, that this specific section can be amended for purposes of

establishing additional cockpits, if the Municipal population so

warrants.

[5]

Shortly thereafter, the Sangguniang Bayan passed an

amendatory ordinance, Municipal Ordinance No. 7 (Ordinance No. 7),

Series of 1993, which amended the aforequoted Section 5 to now read

as follows:

Section 5. Establishment of Cockpit. There shall be allowed to operate

in the Municipality of Daanbantayan, Province of Cebu, not more than

three (3) cockpits.

[6]

On 8 November 1995, petitioner Leonardo Tan (Tan) applied

with the Municipal Gamefowl Commission for the issuance of a

permit/license to establish and operate a cockpit in Sitio Combado,

Bagay, in Daanbantayan. At the time of his application, there was

already another cockpit in operation in Daanbantayan, operated by

respondent Socorro Y. Perea (Perea), who was the duly franchised

and licensed cockpit operator in the municipality since the 1970s.

Perea's franchise, per records, was valid until 2002.

[7]

The Municipal Gamefowl Commission favorably recommended

to the mayor of Daanbantayan, petitioner Lamberto Te (Te), that a

permit be issued to Tan. On 20 January 1996, Te issued a mayor's

permit allowing Tan "to establish/operate/conduct the business of a

cockpit in Combado, Bagay, Daanbantayan, Cebu for the period from

20 January 1996 to 31 December 1996.

[8]

This act of the mayor served as cause for Perea to file a

Complaint for damages with a prayer for injunction against Tan, Te,

and Roberto Uy, the latter allegedly an agent of Tan.

[9]

Perea alleged

that there was no lawful basis for the establishment of a second

cockpit. She claimed that Tan conducted his cockpit fights not in

Combado, but in Malingin, at a site less than five kilometers away from

her own cockpit. She insisted that the unlawful operation of Tan's

cockpit has caused injury to her own legitimate business, and

demanded damages of at least Ten Thousand Pesos (P10,000.00) per

month as actual damages, One Hundred Fifty Thousand Pesos

(P150,000.00) as moral damages, and Fifty Thousand Pesos

(P50,000.00) as exemplary damages. Perea also prayed that the

permit issued by Te in favor of Tan be declared as null and void, and

that a permanent writ of injunction be issued against Te and Tan

preventing Tan from conducting cockfights within the municipality and

Te from issuing any authority for Tan to pursue such activity.

[10]

The case was heard by the Regional Trial Court

(RTC),

[11]

Branch 61 of Bogo, Cebu, which initially granted a writ of

preliminary injunction.

[12]

During trial, herein petitioners asserted that

under the Local Government Code of 1991, the sangguniang bayan of

each municipality now had the power and authority to grant franchises

and enact ordinances authorizing the establishment, licensing,

operation and maintenance of cockpits.

[13]

By virtue of such authority,

the Sangguniang Bayan of Daanbantayan promulgated Ordinance

Nos. 6 and 7. On the other hand, Perea claimed that the amendment

authorizing the operation of not more than three (3) cockpits in

Daanbantayan violated Section 5(b) of the Cockfighting Law of 1974,

which allowed for only one cockpit in a municipality with a population

as Daanbantayan.

[14]

n a ecision dated 10 March 1997, the RTC dismissed the

complaint. The court observed that Section 5 of Ordinance No. 6, prior

to its amendment, was by specific provision, an implementation of the

Cockfighting Law.

[15]

Yet according to the RTC, questions could be

raised as to the efficacy of the subsequent amendment under

Ordinance No. 7, since under the old Section 5, an amendment

allowing additional cockpits could be had only "if the municipal

population so warrants.

[16]

While the RTC seemed to doubt whether

this condition had actually been fulfilled, it nonetheless declared that

since the case was only for damages, "the [RTC] cannot grant more

relief than that prayed for.

[17]

t ruled that there was no evidence,

testimonial or documentary, to show that plaintiff had actually suffered

damages. Neither was there evidence that Te, by issuing the permit to

Tan, had acted in bad faith, since such issuance was pursuant to

municipal ordinances that nonetheless remained in force.

[18]

Finally, the

RTC noted that the assailed permit had expired on 31 December 1996,

and there was no showing that it had been renewed.

[19]

Perea filed a Motion for Reconsideration which was denied in

an Order dated 24 February 1998. n this Order, the RTC categorically

stated that Ordinance Nos. 6 and 7 were "valid and legal for all intents

and purpose[s].

[20]

The RTC also noted that the Sangguniang Bayan

had also promulgated Resolution No. 78-96, conferring on Tan a

franchise to operate a cockpit for a period of ten (10) years from

February 1996 to 2006.

[21]

This Resolution was likewise affirmed as

valid by the RTC. The RTC noted that while the ordinances seemed to

be in conflict with the Cockfighting Law, any doubt in interpretation

should be resolved in favor of the grant of more power to the local

government unit, following the principles of devolution under the Local

Government Code.

[22]

The ecision and Order of the RTC were assailed by Perea on

an appeal with the Court of Appeals which on 21 May 2001, rendered

the ecision now assailed.

[23]

The perspective from which the Court of

Appeals viewed the issue was markedly different from that adopted by

the RTC. ts analysis of the Local Government Code, particularly

Section 447(a)(3)(V), was that the provision vesting unto the

sangguniang bayan the power to authorize and license the

establishment of cockpits did not do away with the Cockfighting Law,

as these two laws are not necessarily inconsistent with each other.

What the provision of the Local Government Code did, according to the

Court of Appeals, was to transfer to the sangguniang bayan powers

that were previously conferred on the Municipal Gamefowl

Commission.

[24]

Given these premises, the appellate court declared as follows:

Ordinance No. 7 should [be] held invalid for allowing, in unconditional

terms, the operation of "not more than three cockpits in Daan

Bantayan (sic), clearly dispensing with the standard set forth in PD

449. However, this issue appears to have been mooted by the

expiration of the Mayor's Permit granted to the defendant which has

not been renewed.

[25]

As to the question of damages, the Court of Appeals agreed with

the findings of the RTC that Perea was not entitled to damages. Thus,

it affirmed the previous ruling denying the claim for damages.

However, the Court of Appeals modified the RTC's Decision in that it

now ordered that Tan be enjoined from operating a cockpit and

conducting any cockfights within Daanbantayan.

[26]

Thus, the present Petition for Review on Certiorari.

Petitioners present two legal questions for determination:

whether the Local Government Code has rendered inoperative the

Cockfighting Law; and whether the validity of a municipal ordinance

may be determined in an action for damages which does not even

contain a prayer to declare the ordinance invalid.

[27]

As the denial of the

prayer for damages by the lower court is not put in issue before this

Court, it shall not be passed upon on review.

The first question raised is particularly interesting, and any

definitive resolution on that point would have obvious ramifications not

only to Daanbantayan, but all other municipalities and cities. However,

we must first determine the proper scope of judicial inquiry that we

could engage in, given the nature of the initiatory complaint and the

rulings rendered thereupon, the exact point raised in the second

question.

Petitioners claim that the Court of Appeals, in declaring

Ordinance No. 7 as invalid, embarked on an unwarranted collateral

attack on the validity of a municipal ordinance.

[28]

Perea's complaint,

which was for damages with preliminary injunction, did not pray for the

nullity of Ordinance No. 7. The Municipality of Daanbantayan as a local

government unit was not made a party to the case, nor did any legal

counsel on its behalf enter any appearance. Neither was the Office of

the Solicitor General given any notice of the case.

[29]

These concerns are not trivial.

[30]

Yet, we must point out that the

Court of Appeals did not expressly nullify Ordinance No. 7, or any

ordinance for that matter. What the appellate court did was to say that

Ordinance No. 7 "should therefore be held invalid for being in violation

of the Cockfighting Law.

[31]

n the next breath though, the Court of

Appeals backtracked, saying that "this issue appears to have been

mooted by the expiration of the Mayor's Permit granted to Tan.

[32]

But our curiosity is aroused by the dispositive portion of the

assailed ecision, wherein the Court of Appeals enjoined Tan "from

operating a cockpit and conducting any cockfights within

Daanbantayan.

[33]

Absent the invalidity of Ordinance No. 7, there would

be no basis for this injunction. After all, any future operation of a

cockpit by Tan in Daanbantayan, assuming all other requisites are

complied with, would be validly authorized should Ordinance No. 7

subsist.

So it seems, for all intents and purposes, that the Court of

Appeals did deem Ordinance No. 7 a nullity. Through such resort, did

the appellate court in effect allow a collateral attack on the validity of

an ordinance through an action for damages, as the petitioners argue?

The initiatory Complaint filed by Perea deserves close scrutiny.

mmediately, it can be seen that it is not only an action for damages,

but also one for injunction. An action for injunction will require judicial

determination whether there exists a right in esse which is to be

protected, and if there is an act constituting a violation of such right

against which injunction is sought. At the same time, the mere fact of

injury alone does not give rise to a right to recover damages. To

warrant the recovery of damages, there must be both a right of action

for a legal wrong inflicted by the defendant, and damage resulting to

the plaintiff therefrom. n other words, in order that the law will give

redress for an act causing damage, there must be damnum et

injuriathat act must be not only hurtful, but wrongful.

[34]

ndubitably, the determination of whether injunction or damages

avail in this case requires the ascertainment of whether a second

cockpit may be legally allowed in Daanbantayan. f this is permissible,

Perea would not be entitled either to injunctive relief or damages.

Moreover, an examination of the specific allegations in

the Complaint reveals that Perea therein puts into question the legal

basis for allowing Tan to operate another cockpit in Daanbantayan.

She asserted that "there is no lawful basis for the establishment of a

second cockpit considering the small population of

[Daanbantayan],

[35]

a claim which alludes to Section 5(b) of the

Cockfighting Law which prohibits the establishment of a second cockpit

in municipalities of less than ten thousand (10,000) in population.

Perea likewise assails the validity of the permit issued to Tan and

prays for its annulment, and also seeks that Te be enjoined from

issuing any special permit not only to Tan, but also to "any other

person outside of a duly licensed cockpit in Daanbantayan, Cebu.

[36]

t would have been preferable had Perea expressly sought the

annulment of Ordinance No. 7. Yet it is apparent from

her Complaint that she sufficiently alleges that there is no legal basis

for the establishment of a second cockpit. More importantly, the

petitioners themselves raised the valid effect of Ordinance No. 7 at the

heart of their defense against the complaint, as adverted to in

their Answer.

[37]

The averment in the Answer that Ordinance No. 7 is

valid can be considered as an affirmative defense, as it is the

allegation of a new matter which, while hypothetically admitting the

material allegations in the complaint, would nevertheless bar

recovery.

[38]

Clearly then, the validity of Ordinance No. 7 became a

justiciable matter for the RTC, and indeed Perea squarely raised the

argument during trial that said ordinance violated the Cockfighting

Law.

[39]

Moreover, the assailed rulings of the RTC, its ecision and

subsequent Order denying Perea's Motion for Reconsideration, both

discuss the validity of Ordinance No. 7. n the Decision, the RTC

evaded making a categorical ruling on the ordinance's validity because

the case was "only for damages, [thus the RTC could] not grant more

relief than that prayed for. This reasoning is unjustified, considering

that Perea also prayed for an injunction, as well as for the annulment

of Tan's permit. The resolution of these two questions could very well

hinge on the validity of Ordinance No. 7.

Still, in the Order denying Perea's Motion for Reconsideration,

the RTC felt less inhibited and promptly declared as valid not only

Ordinance No. 7, but also Resolution No. 78-96 of the Sangguniang

Bayan dated 23 February 1996, which conferred on Tan a franchise to

operate a cockpit from 1996 to 2006.

[40]

n the Order, the RTC ruled

that while Ordinance No. 7 was in apparent conflict with the

Cockfighting Law, the ordinance was justified under Section

447(a)(3)(v) of the Local Government Code.

This express affirmation of the validity of Ordinance No. 7 by the

RTC was the first assigned error in Perea's appeal to the Court of

Appeals.

[41]

n their Appellee's Brief before the appellate court, the

petitioners likewise argued that Ordinance No. 7 was valid and that the

Cockfighting Law was repealed by the Local Government Code.

[42]

On

the basis of these arguments, the Court of Appeals rendered its

assailed ecision, including its ruling that the Section 5(b) of the

Cockfighting Law remains in effect notwithstanding the enactment of

the Local Government Code.

ndubitably, the question on the validity of Ordinance No. 7 in

view of the continuing efficacy of Section 5(b) of the Cockfighting Law

is one that has been fully litigated in the courts below. We are

comfortable with reviewing that question in the case at bar and make

dispositions proceeding from that key legal question. This is militated

by the realization that in order to resolve the question whether

injunction should be imposed against the petitioners, there must be

first a determination whether Tan may be allowed to operate a second

cockpit in Daanbantayan. Thus, the conflict between Section 5(b) of

the Cockfighting Law and Ordinance No. 7 now ripens for adjudication.

n arguing that Section 5(b) of the Cockfighting Law has been

repealed, petitioners cite the following provisions of Section

447(a)(3)(v) of the Local Government Code:

Section 447. Powers, uties, Functions and Compensation. (a) The

sangguniang bayan, as the legislative body of the municipality, shall

enact ordinances, approve resolutions and appropriate funds for the

general welfare of the municipality and its inhabitants pursuant to

Section 16 of this Code and in the proper exercise of the corporate

powers of the municipality as provided for under Section 22 of this

Code, and shall:

. . . .

(3) Subject to the provisions of Book of this Code, grant franchises,

enact ordinances authorizing the issuance of permits or licenses, or

enact ordinances levying taxes, fees and charges upon such

conditions and for such purposes intended to promote the general

welfare of the inhabitants of the municipality, and pursuant to this

legislative authority shall:

. . . .

(v) Any law to the contrary notwithstanding, authorize and license the

establishment, operation, and maintenance of cockpits, and regulate

cockfighting and commercial breeding of gamecocks; Provided, that

existing rights should not be prejudiced;

For the petitioners, Section 447(a)(3)(v) sufficiently repeals

Section 5(b) of the Cockfighting Law, vesting as it does on LGUs the

power and authority to issue franchises and regulate the operation and

establishment of cockpits in their respective municipalities, any law to

the contrary notwithstanding.

However, while the Local Government Code expressly repealed

several laws, the Cockfighting Law was not among them. Section

534(f) of the Local Government Code declares that all general and

special laws or decrees inconsistent with the Code are hereby

repealed or modified accordingly, but such clause is not an express

repealing clause because it fails to identify or designate the acts that

are intended to be repealed.

[43]

t is a cardinal rule in statutory

construction that implied repeals are disfavored and will not be so

declared unless the intent of the legislators is manifest.

[44]

As laws are

presumed to be passed with deliberation and with knowledge of all

existing ones on the subject, it is logical to conclude that in passing a

statute it is not intended to interfere with or abrogate a former law

relating to the same subject matter, unless the repugnancy between

the two is not only irreconcilable but also clear and convincing as a

result of the language used, or unless the latter Act fully embraces the

subject matter of the earlier.

[45]

s the one-cockpit-per-municipality rule under the Cockfighting

Law clearly and convincingly irreconcilable with Section 447(a)(3)(v) of

the Local Government Code? The clear import of Section 447(a)(3)(v)

is that it is the sangguniang bayan which is empowered to authorize

and license the establishment, operation and maintenance of cockpits,

and regulate cockfighting and commercial breeding of gamecocks,

notwithstanding any law to the contrary. The necessity of the qualifying

phrase "any law to the contrary notwithstanding can be discerned by

examining the history of laws pertaining to the authorization of cockpit

operation in this country.

Cockfighting, or sabong in the local parlance, has a long and

storied tradition in our culture and was prevalent even during the

Spanish occupation. When the newly-arrived Americans proceeded to

organize a governmental structure in the Philippines, they recognized

cockfighting as an activity that needed to be regulated, and it was

deemed that it was the local municipal council that was best suited to

oversee such regulation. Hence, under Section 40 of Act No. 82, the

general act for the organization of municipal governments promulgated

in 1901, the municipal council was empowered "to license, tax or close

cockpits. This power of the municipal council to authorize or license

cockpits was repeatedly recognized even after the establishment of the

present Republic in 1946.

[46]

Such authority granted unto the municipal

councils to license the operation of cockpits was generally unqualified

by restrictions.

[47]

The Revised Administrative Code did impose

restrictions on what days cockfights could be held.

[48]

However, in the 1970s, the desire for stricter licensing

requirements of cockpits started to see legislative fruit. The

Cockfighting Law of 1974 enacted several of these restrictions. Apart

from the one-cockpit-per-municipality rule, other restrictions were

imposed, such as the limitation of ownership of cockpits to Filipino

citizens.

[49]

More importantly, under Section 6 of the Cockfighting Law,

it was the city or municipal mayor who was authorized to issue licenses

for the operation and maintenance of cockpits, subject to the approval

of the Chief of Constabulary or his authorized representatives.

[50]

Thus,

the sole discretion to authorize the operation of cockpits was removed

from the local government unit since the approval of the Chief of

Constabulary was now required.

P.D. No. 1802 reestablished the Philippine Gamefowl

Commission

[51]

and imposed further structure in the regulation of

cockfighting. Under Section 4 thereof, city and municipal mayors with

the concurrence of their respective sangguniang panglunsod or

sangguniang bayan, were given the authority to license and regulate

cockfighting, under the supervision of the City Mayor or the Provincial

Governor. However, Section 4 of P.D. No. 1802 was subsequently

amended, removing the supervision exercised by the mayor or

governor and substituting in their stead the Philippine Gamefowl

Commission. The amended provision ordained:

Sec. 4. City and Municipal Mayors with the concurrence of their

respective "Sanggunians shall have the authority to license and

regulate regular cockfighting pursuant to the rules and regulations

promulgated by the Commission and subject to its review and

supervision.

The Court, on a few occasions prior to the enactment of the

Local Government Code in 1991, had opportunity to expound on

Section 4 as amended. A discussion of these cases will provide a

better understanding of the qualifier "any law to the contrary

notwithstanding provided in Section 447(a)(3)(v).

n Philippine Gamefowl Commission v Intermediate Appellate

Court,

[52]

the Court, through Justice Cruz, asserted that the conferment

of the power to license and regulate municipal cockpits in municipal

authorities is in line with the policy of local autonomy embodied in the

Constitution.

[53]

The Court affirmed the annulment of a resolution of the

Philippine Gamefowl Commission which ordered the revocation of a

permit issued by a municipal mayor for the operation of a cockpit and

the issuance of a new permit to a different applicant. According to the

Court, the Philippine Gamefowl Commission did not possess the power

to issue cockpit licenses, as this was vested by Section 4 of P.D. No.

1802, as amended, to the municipal mayor with the concurrence of the

sanggunian. t emphasized that the Philippine Gamefowl Commission

only had review and supervision powers, as distinguished from control,

over ordinary cockpits.

[54]

The Court also noted that the regulation of

cockpits was vested in municipal officials, subject only to the guidelines

laid down by the Philippine Gamefowl Commission.

[55]

The Court

conceded that "[if] at all, the power to review includes the power to

disapprove; but it does not carry the authority to substitute one's own

preferences for that chosen by the subordinate in the exercise of its

sound discretion.

The twin pronouncements that it is the municipal authorities who

are empowered to issue cockpit licenses and that the powers of the

Philippine Gamefowl Commission were limited to review and

supervision were affirmed in eang v Intermediate Appellate

Court,

[56]

Municipality of Malolos v Libangang Malolos

Inc

[57]

and Adlawan v Intermediate Appellate Court.

[58]

But notably

in Cootauco v Court of Appeals,

[59]

the Court especially noted

that Philippine Gamefowl Commission did indicate that the

Commission's "power of review includes the power to

disapprove.

[60]

nterestingly, Justice Cruz, the writer of Philippine

Gamefowl Commission, qualified his concurrence in Cootauco "subject

to the reservations made in [Philippine Gamefowl

Commission] regarding the review powers of the PGC over cockpit

licenses issued by city and municipal mayors.

[61]

These cases reiterate what has been the traditional prerogative

of municipal officials to control the issuances of licenses for the

operation of cockpits. Nevertheless, the newly-introduced role of the

Philippine Gamefowl Commission vis--vis the operation of cockpits

had caused some degree of controversy, as shown by the cases

above cited.

Then, the Local Government Code of 1991 was enacted. There

is no more forceful authority on this landmark legislation than Senator

Aquilino Pimentel, Jr., its principal author. n his annotations to the

Local Government Code, he makes the following remarks relating to

Section 447(a)(3)(v):

12. Licensing power. n connection with the power to grant licenses

lodged with it, the Sangguniang Bayan may now regulate not only

businesses but also occupations, professions or callings that do not

require government examinations within its jurisdiction. t may also

authorize and license the establishment, operation and maintenance of

cockpits, regulate cockfighting, and the commercial breeding of

gamecocks. Existing rights however, may not be prejudiced. The

power to license cockpits and permits for cockfighting has been

removed completely from the Gamefowl Commission.

Thus, that part of the ruling of the Supreme Court in the case

of Municipality of Malolos v Libangang Malolos, Inc et al., which held

that ".the regulation of cockpits is vested in the municipal councils

guidelines laid down by the Philippine Gamefowl Commission is no

longer controlling. Under [Section 447(a)(3)(v)], the power of the

Sanggunian concerned is no longer subject to the supervision of the

Gamefowl Commission.

[62]

The above observations may be faulted somewhat in the sense

that they fail to acknowledge the Court's consistent position that the

licensing power over cockpits belongs exclusively to the municipal

authorities and not the Philippine Gamefowl Commission. Yet these

views of Senator Pimentel evince the apparent confusion regarding the

role of the Philippine Gamefowl Commission as indicated in the cases

previously cited, and accordingly bring the phrase Section 447(a)(3)(v)

used in "any law to the contrary notwithstanding into its proper light.

The qualifier serves notice, in case it was still doubtful, that it is the

sanggunian bayan concerned alone which has the power to authorize

and license the establishment, operation and maintenance of cockpits,

and regulate cockfighting and commercial breeding of gamecocks

within its territorial jurisdiction.

Given the historical perspective, it becomes evident why the

legislature found the need to use the phrase "any law to the contrary

notwithstanding in Section 447(a)(3)(v). However, does the phrase

similarly allow the Sangguniang Bayan to authorize more cockpits than

allowed under Section 5(d) of the Cockfighting Law? Certainly,

applying the test of implied repeal, these two provisions can stand

together. While the sanggunian retains the power to authorize and

license the establishment, operation, and maintenance of cockpits, its

discretion is limited in that it cannot authorize more than one cockpit

per city or municipality, unless such cities or municipalities have a

population of over one hundred thousand, in which case two cockpits

may be established. Considering that Section 447(a)(3)(v) speaks

essentially of the identity of the wielder of the power of control and

supervision over cockpit operation, it is not inconsistent with previous

enactments that impose restrictions on how such power may be

exercised. n short, there is no dichotomy between affirming the power

and subjecting it to limitations at the same time.

Perhaps more essential than the fact that the two controverted

provisions are not inconsistent when put together, the Court

recognizes that Section 5(d) of the Cockfighting Law arises from a

valid exercise of police power by the national government. Of course,

local governments are similarly empowered under Section 16 of the

Local Government Code. The national government ought to be attuned

to the sensitivities of devolution and strive to be sparing in usurping the

prerogatives of local governments to regulate the general welfare of

their constituents.

We do not doubt, however, the ability of the national government

to implement police power measures that affect the subjects of

municipal government, especially if the subject of regulation is a

condition of universal character irrespective of territorial jurisdictions.

Cockfighting is one such condition. t is a traditionally regulated activity,

due to the attendant gambling involved

[63]

or maybe even the fact that it

essentially consists of two birds killing each other for public

amusement. Laws have been enacted restricting the days when

cockfights could be held,

[64]

and legislation has even been emphatic

that cockfights could not be held on holidays celebrating national honor

such as ndependence Day

[65]

and Rizal Day.

[66]

The Whereas clauses of the Cockfighting Law emphasize that

cockfighting "should neither be exploited as an object of

commercialism or business enterprise, nor made a tool of uncontrolled

gambling, but more as a vehicle for the preservation and perpetuation

of native Filipino heritage and thereby enhance our national

identity.

[67]

The obvious thrust of our laws designating when cockfights

could be held is to limit cockfighting and imposing the one-cockpit-per-

municipality rule is in line with that aim. Cockfighting is a valid matter of

police power regulation, as it is a form of gambling essentially

antagonistic to the aims of enhancing national productivity and self-

reliance.

[68]

Limitation on the number of cockpits in a given municipality

is a reasonably necessary means for the accomplishment of the

purpose of controlling cockfighting, for clearly more cockpits equals

more cockfights.

f we construe Section 447(a)(3)(v) as vesting an unlimited

discretion to the sanggunian to control all aspects of cockpits and

cockfighting in their respective jurisdiction, this could lead to the

prospect of daily cockfights in municipalities, a certain distraction in the

daily routine of life in a municipality. This certainly goes against the

grain of the legislation earlier discussed. f the arguments of the

petitioners were adopted, the national government would be effectively

barred from imposing any future regulatory enactments pertaining to

cockpits and cockfighting unless it were to repeal Section 447(a)(3)(v).

A municipal ordinance must not contravene the Constitution or

any statute, otherwise it is void.

[69]

Ordinance No. 7 unmistakably

contravenes the Cockfighting Law in allowing three cockpits in

Daanbantayan. Thus, no rights can be asserted by the petitioners

arising from the Ordinance. We find the grant of injunction as ordered

by the appellate court to be well-taken.

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENED. Costs against petitioners.

Miranda v. Aguirre

Facts: n 1994, RA 7720 converting the municipality of Santiago

toan independent component city was signed into law and

thereafterratified in a plebiscite. Four years later, RA 8528 which

amendedRA 7720 was enacted, changing the status of Santiago from

an CCto a component city. Petitioners assail the constitutionality of

RA8528 because it does not provide for submitting the law

forratification by the people of Santiago City in a proper

plebiscite.ssues:1. WON petitioners have standing. YES.

Rule: constitutionality of law can be challenged by one who will

sustain a direct injury as a result of itsenforcement

Miranda was mayor when he filed the petition, hisrights would

have been greatly affected. Otherpetitioners are residents and voters

of Santiago.1. WON petition involves a political question. NO.

PQ: concerned with issues dependent upon thewisdom, not

legality, of a particular measure,

Justiciable issue: implies a given right, legallydemandable and

enforceable, an act or omissionviolative of such right, and a remedy

granted andsanctioned by law, for said breach of right

Case at bar=justiciable. WON petitioners have rightto a

plebiscite is a legal question. WON laws passedby Congress comply

with the requirements of the Consti pose questions that this court alone

candecide.1. WON the change involved any creation, division, merger,

abolition or substantial alteration of boundaries. YES.

2. WON a plebiscite is necessary considering the change was a

mere reclassification from CC to CC. YES.

A close analysis of the said constitutional provision will reveal

that the creation, division, merger,abolition or substantial alteration of

boundaries of LGUs involve a common denominator material change

in the political and economic rights of the LGUs directly affected as

well as the people therein.t is precisely for this reason that the

Constitution requires the approval of the people "in the political units

directly affected."

Sec 10, Art X addressed the undesirable practice inthe past

whereby LGUs were created, abolished,merged or divided on the basis

of the vagaries of politics and not of the welfare of the people. Thus,the

consent of the people of the LGU directly affected was required to

serve as a checkingmechanism to any exercise of legislative power

creating, dividing, abolishing, merging or alteringthe boundaries of

LGUs. t is one instance where the people in their sovereign capacity

decide on amatter that affects them direct democracy of the people

as opposed to democracy thru people'srepresentatives. This plebiscite

requirement is also in accord with the philosophy of the

Constitutiongranting more autonomy to LGUs.

The changes that will result from the downgrading of the city of

Santiago from an independent component city to a component city are

many and cannot be characterized as insubstantial.

The independence of the city as a political unitwill be

diminished: The city mayor will be placed under theadministrative

supervision of theprovincial governor. The resolutions and ordinances

of the citycouncil of Santiago will have to bereviewed by the Provincial

Board of sabela. Taxes that will be collected by the city willnow have

to be shared with the province.

When RA 7720 upgraded the status of SantiagoCity from a

municipality to an independentcomponent city, it required the approval

of itspeople thru a plebiscite called for the purpose.There is neither

rhyme nor reason why thisplebiscite should not be called to determine

thewill of the people of Santiago City when RA 8528downgrades the

status of their city. There is morereason to consult the people when a

lawsubstantially diminishes their right.

Rule , Art 6, paragraph (f) (1) of the RRs of theLGC is in

accord with the Constitution when itprovides that no creation,

conversion, division, merger, abolition, or substantial alteration of