Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kassian 2010 Hattic-SCauc

Uploaded by

Adyghe ChabadiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kassian 2010 Hattic-SCauc

Uploaded by

Adyghe ChabadiCopyright:

Available Formats

Sonderdruck aus

UGARIT-FORSCHUNGEN

Internationales Jahrbuch

fr die

Altertumskunde Syrien-Palstinas

Herausgegeben von

Manfried Dietrich Oswald Loretz

Band 41

2009

Ugarit-Verlag Mnster

2010

Anschriften der Herausgeber:

M. Dietrich / O. Loretz, Schlaunstr. 2, 48143 Mnster

Manuskripte sind an einen der Herausgeber zu senden.

Fr unverlangt eingesandte Manuskripte kann keine Gewhr bernommen werden.

Die Herausgeber sind nicht verpflichtet,

unangeforderte Rezensionsexemplare zu besprechen.

Manuskripte fr die einzelnen Jahresbnde werden jeweils

bis zum 31. 12. des vorausgehenden Jahres erbeten.

2010 Ugarit-Verlag, Mnster

(www.ugarit-verlag.de)

Alle Rechte vorbehalten

All rights preserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of the publisher.

Herstellung: Hubert & Co, Gttingen

Printed in Germany

ISBN 978-3-86835-042-5

Printed on acid-free paper

Inhalt

Artikel

Bojowald, Stefan

Noch einmal zum Personennamen t 6 6 ww in Urk. IV, 11, 9 ..........................1

Bretschneider, Joachim / Van Vyve, Anne-Sophie / Jans, Greta

War of the lords. The battle of chronology. Trying to recognize historical

iconography in the 3

rd

millennium glyptic art in seals of Ishqi-Mari

and from Beydar..............................................................................................5

De Backer, Fabrice

Evolution of War Chariot Tactics in the Ancient Near East..........................29

Dietrich, Manfried / Loretz, Oswald

Der ugaritische Parallelismus mn || dbb (KTU 1.4 I 3840) und die

Unterscheidung zwischen dbb I, dbb II, dbb III................................................ 47

Dietrich, Manfried / Loretz, Oswald

Ugaritisch nn (Komposit-)Bogenschtze, qt Kompositbogen,

Bogen und qt / Pfeil. Beobachtungen zu KTU 1.17 VI 1314.

18b25a .............................................................................................................. 51

Dietrich, Manfried / Loretz, Oswald

Prventiv-Beschwrung gegen Schlangen, Skorpione und Hexerei

zum Schutz des Prfekten Urtnu (KTU 1.178 = RS 92.2014) ........................ 65

Dietrich, Manfried / Loretz, Oswald

Urbild und Abbild in der Schlangenbeschwrung KTU

3

1.100.

Epigraphie, Kolometrie, Redaktion und Ritual .............................................75

Dietrich, Manfried / Loretz, Oswald

Die keilalphabetischen Briefe aus Ugarit (I). KTU 2.72, 2.76, 2.86, 2.87,

2.88, 2.89 und 2.90........................................................................................... 109

Dietrich, Manfried / Loretz, Oswald

md I Paar und md II Axt, Doppelaxt nach KTU 4.169; 4.363;

4.136; 1.65 ..................................................................................................165

Faist, Betina I. / Justel, Josu-Javier / Vita, Juan-Pablo

Bibliografa de los estudios de Emar (4) .....................................................181

iv Inhalt [UF 41

Galil, Gershon

The Hebrew Inscription from Khirbet Qeiyafa / Neaim.

Script, Language, Literature and History ....................................................193

Gillmann, Nicolas

Quelques remarques additionnelles sur le siege de Lachish........................243

Halayqa, Issam K. H.

A Supplementary Ugaritic Word List for J. Troppers

Kleines Wrterbuch des Ugaritischen (2008)................................................. 263

Halayqa, Issam K. H.

Two Middle Bronze Age Scarabs from Jabal El-Tawain

(Southern Hebron).......................................................................................303

Kassian, A.

Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language .........................................................309

Keetman, Jan

Die Triade der Laterale und ihre Vernderungen

in den lteren semitischen Sprachen............................................................449

Matoan, Valrie / Vita, Juan-Pablo

Les textiles Ougarit. Perspectives de la recherche....................................469

Mazzini, Giovanni

On the Problematic Term syr/d in the New Old Aramaic Inscription

from Zincirli ................................................................................................505

Melchiorri, Valentina

Le tophet de Sulci (S. Antioco, Sardaigne).

tat des tudes et perspectives de la recherche ...........................................509

Murphy, Kelly J.

Myth, Reality, and the Goddess Anat. Anats Violence and

Independence in the Baal Cycle .................................................................525

Nahshoni, Pirhiya / Ziffer, Irit

Caphtor, the throne of his dwelling, Memphis, the land of his

inheritance. The Pattern book of a Philistine offering stand from

a shrine at Nahal Patish. (With an appendix on the technology

of the stand by Elisheva Kamaisky) ............................................................543

Natan-Yulzary, Shirly

Divine Justice or Poetic Justice? The Transgression and Punishment

of the Goddess Anat in the Aqhat Story. A Literary Perspective...............581

Shea, William H.

The Qeiyafa Ostracon. Separation of Powers in Ancient Israel ..................601

2009] Inhalt v

Staubli, Thomas

Bull leaping and other images and rites of the Southern Levant

in the sign of Scorpius .................................................................................611

Strawn, Brent

kwrwt in Psalm 68: 7, Again. A (Small) Test Case in Relating Ugarit to

the Hebrew Bible.........................................................................................631

Sturm, Thomas Fr.

Rabbtum ein Ort der Textilmanufaktur fr den aA Fernhandel

von Assyrien nach Zentralanatolien (ca. 19301730 v.Chr.) ......................649

Zadok, Ran

Philistian Notes............................................................................................659

Buchbesprechungen und Buchanzeigen

W. BERTELMANN u. a. (Hrsg.): Alt-Jerusalem. Jerusalem und Umgebung

im 19. Jahrhundert in Bildern aus der Sammlung von Conrad Schick

und R. HARDIMAN / H. SPEELMAN: Auf den Spuren Abrahams.

Das Heilige Land in alten handkolorierten Photographien

(Wolfgang. Zwickel) ...................................................................................689

Sophie DMARE-LAFONT / A. LEMAIRE (Hrsg.): Trois millnaires de

formulaires juridiques (Oswald Loretz) ......................................................690

Manfried DIETRICH / Walter MAYER: Der hurritische Brief des Duratta

von Mttnni an Amen`otep III. Text Grammatik Kopie. Englische

bersetzung des Textes von Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst. ......................691

Jo Ann HACKETT: A Basic Introduction to Biblical Hebrew (Oswald Loretz) 692

Detlev JERICKE: Regionaler Kult und lokaler Kult. Studien zur Kult- und

Religionsgeschichte Israels und Judas im 9. und 8. Jahrhundert v. Chr.

(Oswald Loretz)...........................................................................................693

Valrie MATOAN (Hrsg.): Le Mobilier du Palais Royal dOugarit

(Alexander Ahrens) .....................................................................................694

Maciej POPKO: Arinna. Eine heilige Stadt der Hethiter (Manfred Hutter).......697

Carole ROCHE (Hrsg.): DOugarit Jrusalem. Recueil dtudes pigra-

phiques et archologiques offert Pierre Bordreuil (Oswald Loretz)........701

Benjamin D. SOMMER: The Bodies of God and the World of Ancient Israel

(Oswald Loretz)...........................................................................................701

Rita STRAUSS: Reinigungsrituale aus Kizzuwatna. Ein Beitrag zur Erfor-

schung hethitischer Ritualtradition und Kulturgeschichte (Piotr Taracha).703

Josef TROPPER / Juan-Pablo VITA: Das Kanaano-Akkadische der

Amarnazeit (Matthias Mller) .....................................................................708

W. H. VAN SOLDT (Hrsg.): Society and Administration in Ancient Ugarit.

Papers read at a symposium in Leiden, 1314 December 2007

(Oswald Loretz)...........................................................................................713

vi Inhalt [UF 41

Jordi VIDAL (ed.): Studies on War in the Ancient Near East. Collected

Essays on Military History (Fabrice de Backer)..........................................713

Abkrzungsverzeichnis.....................................................................719

Indizes

A Stellen .........................................................................................................735

B Wrter .........................................................................................................737

C Namen .........................................................................................................742

D Sachen.........................................................................................................745

Anschriften der Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter ...................................749

Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language

A. Kassian, Moscow

1

1 On the Hattic language (Hattic vocalism, consonantism, nominal and

verbal morphosyntax).............................................................................311

1.1 Hattic vocalism...............................................................................312

1.2 Hattic consonantism.......................................................................312

1.3 Hattic morphosyntax. Nominal wordform (main slots)..................313

1.4 Hattic morphosyntax. Verbal wordform (main slots) .....................313

1.5 ........................................................................................................314

2 Previously proposed West Caucasian attribution....................................314

2.1 General remarks..............................................................................316

2.2 Structural features and morphosyntax ............................................317

2.3 HatticWCauc. root etymologies ...................................................319

2.4 Conclusions ....................................................................................320

3 Previously proposed Kartvelian attribution............................................321

4 Sino-Caucasian hypothesis.....................................................................321

4.1 Sino-Caucasian (or Dene-Sino-Caucasian) macrofamily...............321

4.2 Phonetic correspondences...............................................................322

4.2.1 Vocalism (a very preliminary schema) ................................324

4.2.2 Consonantism......................................................................324

1

I am grateful to Ouz Soysal (Chicago), who has taken pains to read my MS through

and made a number of valuable remarks, additions and corrections to the Hattic data. My

warm thanks go to the participants of the Moscow Nostratic Seminar (Center for Compa-

rative Linguistics of the Institute of Oriental Cultures and Antiquity, Russian State Uni-

versity for the Humanities) for their criticism and general discussion (Vladimir Dybo,

Anna Dybo, Alexander Militarev, Albert Davletshin and others), I am especially indebted

to George Starostin for his help in the compilation of actual lexicostatistical trees of the

Sino-Caucasian macrofamily. The tabarna-problem has been ardently discussed with

Ilya Yakubovich (Chicago/ Moscow). I am grateful to Mark Iserlis (Tel Aviv University)

for his help in archaeological matters. Naturally, all the infelicities are the authors only.

In the present paper I quote Hattic forms after HWHT unless otherwise mentioned.

All forms from Sino-Caucasian languages are generally given after the Tower of Babel

Project databases (Abadet.dbf, Caucet.dbf, Sccet.dbf, Stibet.dbf, Yenet.dbf, Basqet.dbf,

Buruet.dbfsee the list of references) unless otherwise mentioned. I adopt S. Starostins

reconstruction of the Proto-West Caucasian phonological system which is somewhat

different from Chirikbas one (see Starostin, 1997/ 2007 for the nal discussion). Some

AdygheKabardian and Ubykh forms are quoted from , 1957; ,

1977; , 1975; Vogt, 1963standardly without special references.

310 A. Kassian [UF 41

4.2.2.1 Labials ...................................................................327

4.2.2.2 Dentals..................................................................329

4.2.2.3 Alveolar, post-alveolar and palatal affricates.........331

4.2.2.4 Other front consonants...........................................332

4.2.2.5 Laterals ..................................................................333

4.2.2.6 Velar and uvular consonants ..................................334

4.2.2.7 Laryngeals .............................................................334

4.2.2.8 Clusters with *w ....................................................335

4.2.2.9 xK(w)-clusters........................................................336

4.2.2.10 ST-clusters............................................................336

4.2.2.11. lC- and rC-clusters................................................337

4.2.2.12 NC-clusters ..........................................................337

4.2.2.13 Clusters with laryngeals.......................................338

4.3 Root structure .................................................................................338

5 HatticSino-Caucasian root comparisons...............................................340

5.1 Roots with reliable SCauc. cognates ..............................................340

5.2 Loans, dubia, and roots without etymology....................................368

6 HatticSino-Caucasian auxiliary morpheme comparisons .....................397

6.1 Auxiliary morphemes with reliable SCauc. cognates .....................397

6.2 Some auxiliary morphemes with dubious or improbable SCauc.

cognates ..........................................................................................400

7 Contacts with neighboring languages.....................................................402

8 Conclusion..............................................................................................404

8.1 Linguistic afliation .......................................................................404

8.2 Geographical problem....................................................................416

9 Phonetic symbols. Language name abbreviations. References ..............433

9.1 Phonetic symbols (selectively) .......................................................433

9.2 Language name abbreviations ........................................................434

9.3 References ......................................................................................435

Abbreviations....................................................................................................446

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 311

1 On the Hattic language (Hattic vocalism, consonantism,

nominal and verbal morphosyntax)

Hattic is an ancient unwritten language spoken in Central Anatolia at the begin-

ning of the 2

nd

millennium BC and in all likelihood earlier. We have to suppose

that Hattians were Anatolian autochthons before the Hittite-Luwian migrations

in this region (more about the sociolinguistic situation see Goedegebuure,

2008).

2

The Hattic language is known only in Hittite cuneiform transmission

(ca. 16501200 BC), with the exception of some personal names from Old As-

syrian Cappadocian colonies (the early 2

nd

millennium BC).

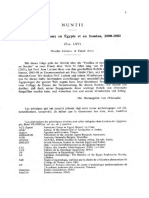

Fig. 1. Anatolia, the second half of the 3

rd

the rst half of the 2

nd

millennia BC.

The map reects only known linguistic units

2

The Alaca Hyk royal tombs as well as the corresponding sites in the Hatti Heart-

land of the 3

rd

millennium BCKalnkaya, Resulolu and others, see, e. g., Zimmer-

mann, 2009, Yildirim/ Zimmermann, 2006require Hattic attribution. It is not clear to

me on what evidence some scholars (e. g., Bryce, 2005, 14) attribute the Alaca Hyk

tombs to the Hittito-Luwians. We know that the Hattians had institution of kingship, de-

veloped pantheon and were metal-workersit ts the Alaca Hyk culture very well.

But we cannot say the same about the prehistoric Hittito-Luwian tribes known to us. The

traditional (pre-C

14

) dating places Alaca Hyk tombs in the second half of the 3

rd

mil-

lennium BC, although . Yalin in New investigations on the royal tomb of Alacah-

yk (paper presented on May 27 at the Meeting on the Results of Archaeometryses-

sion of the 32

nd

International Symposium of Excavations, Surveys and Archaeometry, or-

ganized by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Republic of Turkey, May 2428, 2010,

Istanbul) reported that the recent C-14 analysis of a wooden fragment from the old 1930s

excavations gave the date from 2 500 to 10 000 BC [sic!], but this result is not very re-

liable (I am grateful to Thomas Zimmermann, Ankara, for this reference).

312 A. Kassian [UF 41

The modern state of research in the Hattic language is reected in the

publications of O. Soysal, especially in his brilliant monograph HWHT. Now we

can postulate ca. 300 Hattic roots and stems; the meanings of ca. 200 of them

are established with different degrees of reliability (for the list of Hattic lexemes

see Soysal, HWHT, 274 ff.).

For a short sketch of the Hattic grammar, which is based mostly on HWHT,

see , 2010.

1.1 Hattic vocalism

i

u

e (?)

a

Signs of the E-series can reect the phoneme /e/ or be a mere graphical

phenomenon, since there are a lot of examples where I- and E-signs freely alter-

nate.

1.2 Hattic consonantism

p t

k

/

f s

h

m n

w l, r j

Consonants can be graphically geminated and non-geminated in the intervocalic

position (a-ta vs. at-ta), but it seems that this graphical phenomenon is signi-

cantly less regular than the same opposition in Hittite (where Hitt. -t- < IE *d,

*dh; Hitt. -tt- < IE *t). It is very likely that Hattic had two or more consonant se-

ries (e. g., voiceless ~ voiced, lax ~ tense or ejective ~ aspirate ~ plain), but this

opposition differed phonetically from the analogous opposition in Hittite and

Hittite scribes met with difculties in transferring their graphical method onto

Hattic texts.

/f/ is postulated for the ligatures wa

a

, we

e

, wi

i

, wu

u

, wu

, pu

u

, wi

p

, wu

pu

and

for the cases where we see an alternation of W- and P-signs. Such an alternation

is very frequent in known Hattic texts. Since the Hattic corpus is too small, it is

unclear whether every p may alternate with w or w-ligature (and vice versa:

whether every w may alternate with p and w-ligature). From the formal view-

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 313

point we should postulate only two labial phonemes in Hattic/m/ and /f/and

eliminate /p/ and /w/ from the table above. In the etymological studies below I

am impelled to treat p, w and f as one phoneme.

// is expressed by the signs of Z-series.

/s/ is written by the signs of -series. Sporadical usage of S-signs (OS+) may

reect the second sibilant (e. g., //), but the available data are too scant.

In some morphemes (both root and auxiliary) we see a free alternation of T-

and -signs. I postulate something like // for these cases, but, e. g., interdental

fricative // is, of course, an equivalent solution here.

/h/velar or post-velar (e. g., laryngeal) fricative, expressed by the -signs.

In Akkadian -series reects a phoneme, which originates from the Semitic

voiceless uvular fricative *; in Hittite graphical h covers velar/uvular spirant

(Patri, 2009, 107 ff.).

1.3 Hattic morphosyntax. Nominal wordform (main slots)

5

particles

4

(?)

3

locative

preposition

2

possessive

pronoun

1

number

0

root

1

case

2

particles

ma/ fa a, i fe, ha, ka,

zi

u

le, e/ te

ai?

up (uf?)

if(a)

fa/

a/ i

u/ tu

n

i

1.4 Hattic morphosyntax. Verbal wordform (main slots)

9

negation

8

opta-

tive

7

subject

6

?

5

direct

object

4

locus

3

locus

2

locus

1

?

0

root

1

tense,

mode,

aspect

2

particles

ta/

a/

te/

e

ta/ te fa

u, un

a?

ai, e, i

tu/ u h, k,

m, n

p, , t,

w(a),

wa

a

ta, za,

e, te,

tu

h(a),

ha,

ka,

za?,

pi, wa

k(a),

zi

f(a) u

e

a

ma, fa,

pi

(=?),

a/ at

314 A. Kassian [UF 41

1.5 The genetic attribution of Hattic is debatable. There are two main

theories, advocated by various scholars: West Caucasian and Kartvelian.

3

2 Previously proposed West Caucasian attribution

The West Caucasian family consists of a relatively small number of languages:

1) Abkhaz, Abaza; 2) Adyghe, Kabardian; 3) Ubykh.

The modern West Caucasian reconstruction was made by S. Starostin (see

NCED, Caucet.dbf, Abadet.dbf), later it was veried and partly modied by

V. Chirikba (Chirikba, 1996). Some important details were more explicitly stated

in Starostin, 1997/ 2007.

According to the glottochronological procedure, the North Caucasian proto-

language split into East Caucasian and West Caucasian branches ca. 3800 BC. In

its turn West Caucasian split into Abkhaz-Abaza, Ubykh and Adyghe-Kabardian

ca. 640 BC.

The following tree of the NCauc. family (g. 2) is based on 50-wordlists of

the majority of modern NCauc. languages. The 50-wordlist includes the 50 most

stable items from the classical Swadesh 100-wordlist. The procedure consists

of the subsequent reconstruction of corresponding wordlists for intermediate

proto-languages and screening of synonyms at every stage.

4

The primary

lexicographic data which were used can mostly be found in the database section

of the Tower of Babel Project. The tree has been compiled by the author as part

of the ongoing research on the Preliminary Lexicostatistical Tree of the worlds

languages (within the Evolution of Human Language project, supported by the

Santa Fe Institute). The tree on g. 2 is preliminary, maybe some nodes will be

corrected as a result of further researches, but it gives the general frame of the

NCauc. family.

The next tree (g. 3) represents the WCauc. branch. The tree is based on

classic 100-wordlists and compiled according the standard procedure.

5

3

Sometimes more exotic attributions are proposed. E. g., Fhnrich, 1980 tries to show

the specic relationship between Hattic and Cassite or Hurrian, but I must accede to Soy-

sals criticism of Fhnrichs comparisons (see HWHT, 34 ff.).

4

For this kind of glottochronological procedure see detailed in Starostin G., 2010. For

the general principles of the Swadesh wordlist compilation process now see Kassian et

al., 2010.

5

For this kind of glottochronological procedure see Starostin, 1989/ 1999.

2

0

0

9

]

H

a

t

t

i

c

a

s

a

S

i

n

o

-

C

a

u

c

a

s

i

a

n

L

a

n

g

u

a

g

e

3

1

5

Fig. 2. Glottochronological tree of the North Caucasian family (50-item wordlist-based)

Fig. 3. Glottochronological tree of the West Caucasian branch (100-item wordlist-based)

316 A. Kassian [UF 41

For the rst time the structural similarity between Hattic and West Caucasian

languages was noted by E. Forrer (1921, 25; 1922, 229). Later J. von Mszros

(1934, 27 ff.) gave the list of grammatical and lexical isoglosses between Hattic

and Ubykh. Further the idea of the West Caucasian attribution of Hattic was sup-

ported by I. Dunaevskaja (, 1960; , 1961, 134 f.gram-

matical features), I. Diakonoff (, 1967, 172 ff.Hattic afxes),

Vl. Ardzinba (, 1979grammatical features), Vja. Ivanov (in a num-

ber of publications; see , 1985 for the summed up list of Hattic roots and

auxiliary morphemes with WCauc. cognates), Viach. Chirikba (Chirikba, 1996,

406Hattic roots and afxes, structural features), and Jan Braun (,

1994Hattic roots; , 2002Hattic local prexes). It must be noted that

after the outdated von Mszros list of cognates it was Ivanov, who for the rst

time made an attempt to prove the West Caucasian hypothesis by a scientic ap-

proach. Despite the fact that I do not agree with the West Caucasian attribution

of Hattic, Ivanovs publications denitely got the problem of Hattic etymology

off the ground and serve as a good start point for subsequent studies.

The following difculties arise when one attempts to compare Hattic with

WCauc. languages.

2.1 General remarks

2.1.1 Attested Hattic chronologically is more ancient than the late Proto-

WCauc. language by almost 1000 years. Therefore it is possible to compare Hat-

tic forms only with the WCauc. forms, which can be assuredly reconstructed for

the Proto-WCauc. level.

An example. Chirikba, 1996, 414 compares Hattic zi- (a nominal prex with

ablative semantics, e. g., from top-down) with AbkhazAbaza *(a- under,

*(- from down. As a matter of fact AbkhazAbaza *(a-/ *(- has doubtless

cognates in the other WCauc. languages: AdygheKabardian *ca- under,

Ubykh -(a bottom, lower part, etc., so we must reconstruct WCauc. *\V bot-

tom, lower part ; under (preverb) here (< NCauc. *H\n bottom), and

immediately the comparison with Hattic zi- becomes phonetically unlikely (for

regular NCauc. *\ ~ Hatt. l see below).

2.1.2 As is known, the rst Indo-Europeanists of the XVIII c. used to pro-

pose etymological comparisons like follows (e. g., RussianGerman): pri-nes-i

bring! (2 sg.) ~ bringen Sie or u-bi-l he has killed ~ bel and so on. Un-

fortunately some of the authors mentioned above get caught in the same pitfall.

An example. The Hattic well-attested lexeme (a)haf god has a regular

plural form fa-haf deities. Von Mszros, 1934, 32, , 1985, 37 and

Chirikba, 1996, 425 compare fa-haf with the AdygheKabardian and Ubykh

compounds of WCauc. *wa sky; god + *a grey; powder: AdygheKa-

bardian *wa-a sky (< grey sky), Ubykh wa-a thunder and lightning

6

6

Not god, see , 1977 2, 89 f.

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 317

(< heavenly blasting powder). Such a comparison can hardly be accepted.

2.1.3 There is an old comparison of Slav. *medv-d bear (< one who

eats honey) and OInd. madhv-d- Ses essend (said of birds in Rig-Veda).

But despite the exact phonetic regularity it is hard to reconstruct such a

compound for the Proto-IE level, since tatpurua madhv-d- is formed after a

synchronically regular and very productive model and there are not any reasons

to suspect a Proto-Indic stem here rather than an occasional word-forming in a

poetic text. We see the same situation with some previously proposed Hattic

WCauc. etymologies.

An example. Hatt. verb tuh to take is compared by Chirikba, 1996, 419

with Abkhaz *t- to take from inside, where *t is a standard locative pre-

verb and * means to take (< WCauc. *x to take). This comparison is not

reliable, since Hattic is almost 3000 years distant from the split of the Common

AbkhazAbaza proto-language (see g. 3 above) and we know that local prever-

bation is a living and productive model of forming verbal stems in the modern

AbkhazAbaza dialects.

2.1.4 A great part of previously proposed comparisons must be rejected now

with certainty, since they were based on erroneous and out-of-date interpretation

of the Hattic data. On the other hand, sometimes scholars operate with incorrect

WCauc. forms.

Examples. , 1967, 173 compares Hatt. fa-/ - (plural of the nomina-

tive and oblique cases) with Abkhaz -wa (a plural marker of the animate class),

but in reality Abkhaz -wa forms the names of races (both in singular and plural),

see Hewitt, 1979, 149. In his turn , 1994, 20 compares Hatt. malhip good,

favorable with Adyghe mk property, fortune, which in fact is a recent

Arabic loanword (Arab. mulk ownership, property, see , 1977 1,

272).

2.2 Structural features and morphosyntax

2.2.1 All the authors mentioned above note the similarity between the Hattic

polysynthetic verbal wordform, where prexation prevails, and the same pheno-

menon in WCauc. languages (cf., e. g., Abzakh verbal scheme in Paris, 1989,

196 ff.). As a matter of fact, the reconstruction of Proto-WCauc. morphosyntax

is the task of future research, today we can operate with modern Abkhaz

Adyghe paradigms only.

2.2.2 Second, it is clear that the Hattic verbal wordform does not coincide

directly with attested WCauc. schemas. We can speak about typological similari-

ty only and suggest monophonemic comparisons between some Hattic and

WCauc. afxes.

2.2.3 Third, polysynthetic verbal morphosyntax is characteristic of some

other branches of Sino-Caucasian macrofamily, not only of the WCauc. sub-

branch. See , 1999 for the Proto-Yenisseian verbal reconstruction,

318 A. Kassian [UF 41

Berger, 1998 1, 104 for the Burushaski verbal wordform (Hunza-Nager dialect)

and, e. g., Holton, 2000, 163 ff. for Tanacross, which possesses verb structure

typical of Na-Dene languages. Yenisseian, Burushaski and Na-Dene schemas are

also rather similar to the known Hattic verbal wordforms, therefore we cannot

speak about exclusive HatticWCauc. connection in this case. On the contrary,

we must suppose that polysynthetic verbal morphosyntax with prexation was

characteristic of the Sino-Caucasian proto-language (this feature was almost

completely destroyed in the Sino-Tibetan family due to contacts with isolating

Austric languages,

7

and was seriously rebuilt in the East Caucasian sub-

branch

8

).

2.2.4 Fourth, we cannot say that the most part of Hattic auxiliary mor-

phemes nds its counterparts in WCauc. languages. On the contrary, the authors

mentioned above operate with individual afxal comparisons and fail to

reconstruct hypothetical Proto-HatticWCauc. sets of grammatical morphemes.

9

An appreciable part of HatticWCauc. afxal comparisons, which were pre-

viously proposed, must be rejected now, since they are based on the incorrect

interpretation of the Hattic grammatical system. On the other hand, the majority

of reliable HatticWCauc. afxal comparisons possesses cognates in East Cau-

casian sub-branch of the NCauc. family or in other families of SCauc. macro-

family, and it is impossible to speak about exclusive HatticWCauc. isoglosses

in these cases.

An example. The Hattic genitive marker -n is standardly compared with

WCauc. *-n (ergative and general indirect case; possessive case; transforma-

tive case). As a matter of fact WCauc. *-n goes back to the Common NCauc.

genitive sufx *-nV: Nakh *-n (genitive; adjective and participial sufx; inni-

tive), Av.-And. *-nV (ablative; translative), Lak -n (dative I, lative, innitive),

Lezgh. *-n (genitive; elative; temporal ; suff. of adjectives and participles;

7

See Benedict, 1972 for morphological relicts in the languages of the Sino-Tibetan

family.

8

See Bengtson, 2008, 97 ff. for similar conclusions about this ECauc. innovation. Cf.,

e. g., , 1960 for the rests of the verbal prexal polysynthetism in the ECauc.

languages. Quite differently Chirikba, forthc. a and forthc. b, who claims that Proto-

North Caucasian was an analytic language, while Pre-Proto-West Caucasian developed

into an isolating (Chinese-like) formation, but I do not understand on which positive evi-

dence Chirikbas syntactical theory is based.

9

Chirikba, 1996, 412 ff. and , 2002 make attempts to etymologize the system of

Hattic local prexes integratedly. In reality the only reliable exclusive Hatt.WCauc. iso-

gloss in their lists is the Hatt. verbal local prex ta- ~ WCauc. preverb *tV- in; super.

On the contrary, Common NCauc. etymologies for Hatt. ha- and ka- are not less probable

than Narrow WCauc. ones. The meaning and function of Hattic ni- / nu- are unknown

(see HWHT, 232 f.). Verbal li- does not exist. Nominal zi- / za- and fe- cannot be com-

pared with WCauc. *\V- and *a- on phonetical grounds. The morpheme ta- is found

only in the totally opaque compound itarrazil earth [22] ; the same concerns the mor-

pheme kil, which has been arbitrarily singled out from kiluh runner-spy [33] by

J. Braun.

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 319

terminative; ergative).

2.2.5 Chirikba, 1996, 407 ff. lists structural parallels between Hattic and

WCauc. languages, but unfortunately almost all of them do not seem persuasive.

a) The grammatical system of Hattic is debatable. It is an open question

whether Hattic was a nominative-accusative, ergative (e. g., Taracha, 1988) or

active language (for split activity theory see Goedegebuure, 2010). Although an

ergative pattern seems most probable for Hattic, it cannot prove genetic relation-

ship, but rather represent an areal feature (cf., e. g., the neighboring Hurrian lan-

guage).

b) The Hattic case system is not so rudimentary from the typological view-

point (cf. the schema above).

c) The role of word formation compounding in Hattic is comparable rather

with East Cauc. languages and some other Sino-Caucasian languages

10

than with

WCauc. dialects.

d) For verbal polysynthetism with prevailing prexation see above, 2.2.3.

e) Unmarked nominal plural forms which are sometimes attested in Hattic

texts is the same case as verbal polysynthetismit is not an exclusive Hattic

WCauc. isogloss. The phenomenon of unmarking plural in nouns is known from

other Sino-Caucasian languages: for the Yenisseian family see Castrn, 1858,

16 ff., / , 1968, 235 ff. ; for Na-Dene Holton, 2000, 157 ff. (the

Tanacross language).

f) The restriction on initial r- is a common areal feature, known at that epoch

from East Caucasian languages to Ancient Greek dialects.

g) Some listed Hattic phonetic features cannot be included in the compari-

son, since the Hittite cuneiform gives no reliable data for such an analysis and,

second, we know too little about the Hattic morphonology and phonetic sandhi.

2.3 HatticWCauc. root etymologies

As is known, the normal Proto-NCauc. nominal root had the shape CVCV,

where C is a consonant or a combination of consonants; the standard Proto-

NCauc. verbal root looked like =VCV(R), where = is a class marker, Can

obstruent consonant or a combination of consonants, Ra sonorant (see NCED,

82 ff.). These structures were seriously rebuilt in the WCauc. proto-language,

where the prevailing shape of nominal and verbal roots became CV.

In its turn the standard Hattic root (both nominal and verbal) is CVC, where

C can be a combination of consonants.

Thus, there are three hypothetical ways to compare Hattic with Proto-

WCauc.

2.3.1 We may assume that the reduction of the root structure in Proto-

WCauc. language took place after Hattic had set apart. But in this case we must

compare Hattic directly with the NCauc. proto-language, not with the WCauc.

10

E. g., with Yenisseian (see , 1968).

320 A. Kassian [UF 41

proto-language as it is today reconstructed on the basis of known WCauc. dia-

lects.

2.3.2 We can divide Hattic roots into C- or CV- root nucleus with some

consonant extensions of unknown nature. This method is accepted in a number

of Vja. Ivanovs and J. Brauns etymologies (e. g., , 1985, 11, 20, 22,

50, 58, and so on; , 1994), but it is clear that it is the way to nowhere.

2.3.3 Finally we can compare Hattic roots with compounds or inected

forms from the modern WCauc. dialects. Of course, with such approach we

immediately get caught in bringen-Sie- or madhvad-pitfalls, for which see

2.1.22.1.3 above.

An example. , 1985, 45 compares Hatt. ul to let, to let in with

Ubykh ca-w-la to let, release exhaustively, where ca- is a preverb used with

verbs of motion (Vogt, 1963, 104), w is a frequent verbal root to enter, go

(< WCauc. *V to enter < NCauc. *=or to go, walk, enter), while -la is a

regular exhaustive sufx.

2.4 Conclusions

2.4.1 Hattic cannot be directly compared with WCauc. due to the fundamental

difference in root structure. Grammatical Hatt.WCauc. isoglosses are also

rather weak.

2.4.2 Indeed, Hattic possesses a number of monoconsonantal roots which

can be compared with WCauc. data, but in almost all these cases proposed

WCauc. roots have reliable NCauc. cognates, therefore such comparisons cannot

prove an exclusive HatticWCauc. relationship.

An example. , 1994, 19 compares Hatt. root zuwa- in sufxed zuwa-tu

wife with WCauc. *p-zV female; bitch (AbkhazAbaza *ps, Adyghe

Kabardian *bz, Ubykh bza, with the frequent Proto-WCauc. prex *p-). In

reality WCauc. *-zV is not an isolated form, but goes back to NCauc. *

wjV

(~ -I-) woman, female (further to SCauc. *wjV (~ s-, ~ -I-) female), and

the direct HatticNCauc. or HatticSCauc. comparison is self-suggesting.

2.4.3. Even if we undertake a monophonemic etymologization of Hattic

CVC-roots, the genetic relationship to the WCauc. sub-branch cannot be proved,

since the regularity of phonemic correspondences in monophonemic compari-

sons must be established by a solid corpus of cognates that is not the case.

2.4.4. A great part of HatticWCauc. isoglosses which were previously

proposed need to be left out, since they are based on incorrect and out-of-date

Hattic data.

2.4.5. It is worth noting, however, a small number of probable WCauc. loan-

words in Hattic, for which see Section 7 below.

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 321

3 Previously proposed Kartvelian attribution

Girbal, 1986, 160163 proposes four HatticKartvelian root etymologies, two of

them are striking: Hatt. tumil rain ~ Kartv. *wim- to rain and Hatt. am(a)

to hear (vel sim.) ~ Kartv. *sem- to hear. Of course, genetic relationship can-

not be established by a couple of comparisons (even if they belong to the

Swadesh wordlist), and we must treat these etymologies as chance coincidences.

Note that Hatt. tumil and am(a) possess reliable SCauc. cognates. Gabeskiria,

1998 attempted to add some new Kartvelian cognates of Hattic lexemes, but

without much successfor the criticism of Gabeskirias studies see HWHT,

33 f.

4 Sino-Caucasian hypothesis

Although the WCauc. attribution of Hattic is improbable, it is very likely that

Hattic represents a separate branch of the Sino-Caucasian macrofamily. Below I

list a number of Hattic root and auxiliary morphemes with probable SCauc. cog-

nates. It is important that the percentage of the so called basic vocabulary in my

list is relatively high. Of course, the regularity of the assumed phonemic corre-

spondences between Hattic and Proto-SCauc. cannot be proved due to the

scantiness of Hattic lexical data, but it should be noted that :

a) the main part of the proposed phonemic correspondences are trivial (e. g.,

SCauc. *p ~ Hatt. f, SCauc. *( ~ Hatt. t, SCauc. * ~ Hatt. t~ (//?), SCauc. * ~

Hatt. l, SCauc. *k ~ Hatt. k and so on);

b) some special types of phonetic developments (e. g., consonant cluster

simplication) are very typical of the other daughter proto-languages of the

SCauc. macrofamily, and therefore can be regarded as common innovations.

4.1 Sino-Caucasian (or Dene-Sino-Caucasian) macrofamily

For the rst time the genetic relationship between three proto-familiesNorth

Caucasian, Yenisseian and Sino-Tibetanwas partially substantiated on the

ground of regular phonetic correspondences in , 1982/ 2007. Some

other papers by the same author, dedicated to the Sino-Caucasian problem, can

be found in , 2007 (both in Russian and English). For the preliminary

comparative phonetics of the Sino-Caucasian macrofamily see SCC (this work

was not nished and therefore remains unpublished). The highly preliminary

Sino-Caucasian etymological dictionary is available as Sccet.dbf.

As in the case of the NCauc. family (g. 2) the following preliminary Sino-

Caucasian tree is based on 50-wordlists (see com. on g. 2 above for detail). The

tree has been compiled by G. Starostin (pers. comm.) as part of the ongoing re-

search on the Preliminary Lexicostatistical Tree of the worlds languages (within

the Evolution of Human Language project, supported by the Santa Fe Insti-

322 A. Kassian [UF 41

tute): g. 4.

11

The tree gives the general frame of the SCauc. macrofamily, but it must be

stressed that the tree cannot be regarded as a nal solution. During the continu-

ing studies of SCauc. daughter families this schema will probably be improved.

Three main proto-languages are the basis of the SCauc. reconstruction:

North Caucasian, Sino-Tibetan and Yenisseian. They possess relatively well-

done comparative grammars (especially phonetics) and etymological dictionaies.

NCauc. familyCaucet.dbf, which has been published as NCED (w. lit.). STib.

familyStibet.dbf, based on Peiros/ Starostin, 1996 (w. lit.), but seriously im-

proved. Yen. family, 1982/ 2007 and Yenet.dbf, based on -

, 1995 and Werner, 2002 with additions and corrections.

The Proto-Na-Dene reconstruction is not done (or not published) yet, there-

fore I do not use Na-Dene data in my paper. Isolated Burushaski and Basque

also do not provide considerable help due to natural reasons.

4.2 Phonetic correspondences

Below I quote phonetic charts from SCC, 24 ff. and add the Hattic column with

suggested Hattic counterparts. As it was said above, unfortunately S. Starostin

did not manage to nish SCCin particular it concerns the phonetic charts,

whose cells are sometimes incomplete or, on the contrary, redundant. Despite

this fact, the tables are quoted as they have been compiled by S. Starostin with

the exception of few cells important to us, which I corrected,these cells are

marked by footnotes.

The correspondences are illustrated by the Hattic examples taken from sec-

tions 5.1 and 6.1.

11

Position of the Hurro-Urartian proto-language is not quite clear. Pace the work Diako-

noff / Starostin, 1986, where Hurro-Urartian is traditionally included into the ECauc.

stock of the NCauc. family, it is very likely that this cluster represents a separate branch

of the SCauc. macro-family (at the beginning of the 2000s S. Starostin himself tended to

lean towards the same conclusion). Because of many lacunae in the Hurrian 50-wordlist

it is impossible to process Hurrian using the formal algorithm (Hurrian is not included in

the tree on g. 4), but it is clear that Hurro-Urartian belongs to the NCauc.Yen. branch,

not to the STib.Na-Dene one, and some isoglosses may prove the specic relationship

between the Hurro-Urartian and Yen.Burush. stocks. See Kassian, 2010 for some

details. The Na-Dene branch on g. 4 does not include the Haida language.

2

0

0

9

]

H

a

t

t

i

c

a

s

a

S

i

n

o

-

C

a

u

c

a

s

i

a

n

L

a

n

g

u

a

g

e

3

2

3

Fig. 4. Glottochronological tree of the Sino-Caucasian macrofamily (50-item wordlist-based)

324 A. Kassian [UF 41

4.2.1 Vocalism (a very preliminary schema)

SCauc. NCauc. STib. Yen. Burush. Hattic

*i i, e e, i () i i

*e e, i a, a, e (), a, e

i / e,

(ae, a)

* a, i, e e (), i, a, e a, (i / e)

* , , i i, i i / e

* , a, , e a, , o o, a a, i / e

*a a e, a,

a (), e (),

a, e (i) a, (u)

*u o, u u, o o (), u u, o

*o o, u , a u, , o a, o (u)

u

Consonant cluster simplications may cause a preceding vowel change:

SCauc. *\npV tongue; lip; to lick > alef tongue [1]

SCauc. *xlw forelock; horn > kai horn [14]

Yen. *t[e]mb-V- root ~ tup root [63]

4.2.2 Consonantism

Below for Hattic I use cuneiform notation: for /s/, z for //, t~ for //.

SCauc. NCauc. STib. Yen. Burush. Hattic

*p p ph, -p p ph-, p

* , b p-, -p b p

*b b p, ph, -p p b

f / p/ w

*m m m b- / p- / w-, m m f- / p- / w-, m

*w w () w/ 0 0-, w/ 0 b-, 0(u)

w-, -u-, -f-,

(-m-)

*t t th, -t d th

* t, -t d t, ()

*d d t, th, -t t t, ()

t, z (_i)

*n n n d-, n n n

*r r r - / t-, r, r

1

d-, r -, -r-, (-l-)

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 325

SCauc. NCauc. STib. Yen. Burush. Hattic

*c c ch/ s, -t s s

* ( C, -t c, s - ~ -, s

t-, z- (_i / e), z-,

--

* ch, h , s s

*s s s ( / ch), -0 s, d-(V) d-, s -

*z z ,

* , ,h, -t -, s s/ , / (, -

* ( , ,h, , -t s, c (h), ,/

, -

t-, -t-, -z- (_i)

*j , , -t -, s

12

,- /

-, s/ ( / )

* s ( / ch), -0 s, d-(V) d-, / (V)

* ?

* , ,h -( / -), s / , / (, -

* ( , ,h , / , / (, -

-~t-, t-, z- (_i),

--

* , , / (, , t

* -, -0 s, d-(V) s/ /

* r rj

1

, r d-, r

* n -, , n n

*j j j j, 0 j, 0 -0-

* r(..L), -k j-, lt-, lt / l

*\ \

, l, r(..L),

-k/ -

j-, l, lt-, lt / l

* , l, -k r, r

1

lt-, lt / l

l

* l, j-, l, lt- (l-), ld

* l-, -, -l d-, l, r

1

, r

13

l r, (l)

*l l r d-, l ~ r, r

1

l l

12

Updated cell.

13

Updated cell.

326 A. Kassian [UF 41

SCauc. NCauc. STib. Yen. Burush. Hattic

*k k k-, -k g, -k- k(h)

* kh, gh, -k g-, -k, -g- k

k

*g g k-, -k k g

*x x -, -0 x, ~ G h h

* g q ~

* n b-, 0-, f-, n

*q q

qh-, G-, x-,

- ; -k/ -

q-, q/ G q(h),

*q q Gh-, q; -k, - q-, q/ G q(h),

k

*G G

q, qh-,

[G(h)-], k/ -

x-/-, q/G q(h),

* , , qh-, -0 , x h h

* G-, q-, , -j / -w , G 0/

*

0 () ; w >

- ~ -

-, j ; w >

h/ x

0/ h/ j

* 0; w > ()-

-, j, 0; w >

h/x

0/ h/ j

* 0; w > - ; w > h/x 0/ h/ j

*h h

0; hw >

(/ -, w-)

-, j ; hw >

h/ x

0/ h/ j 0

*

0; w > j-,

w- (/-)

-, j,

14

0/h/j h, (0)

* 0; w > ?

-, j ; w >

h/ x

0/ h/ j (0)

*xm ? f m w-

*x ? x

*w m b-, m-, -n/ -m

*xw f b-, h-

14

Updated cell.

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 327

SCauc. NCauc. STib. Yen. Burush. Hattic

*xg g k~q, -, -k q, x, g k, h

*xk k-,-k q-, q/ G () h-,-q-,-

*x

k-, kh- ~ gh-

~ qh-, -k

q, G, qh, , -q k, h

*xq q k, g, -k q, , x

15

qh, , -q h

*xqw qw k, g, -k x, g k, g k

*xq q gh, (k) q, , x qh, h

*xqw qw k, kh x, g k, g k

*xG G, () g, kh q, , x qh, , q

*xG*w Gw ghw, kw k k, g

*sd c(h) t c (~ ch, (h)

*st c ch/ s, -t(s), -s t c

*s ( ch/ s t c ( ~ () t

*d ~ ,h ? ch

*t c ? ?

* ( , h t ?

*d t (h), ,

*t , t ? t-, -z- (_i)

* ( ? t h

4.2.2.1 Labials

SCauc. *p, *, *b merge in Hatt. f / p/ win all likelihood more than one pho-

neme, but can hardly be distinguished due to the imperfect and inconsistent

cuneiform transcription:

SCauc. *\npV tongue; lip; to lick > alef tongue [1]

SCauc. *q[]pV to cover > kip to protect [18]

SCauc. *[p]r lightning; brilliance > paru bright [33]

SCauc. *aplxqwE leaf > puluku leaves [39]

SCauc. *[p]HV to blow (STib. *bt) > pu-an to blow on [43]

15

Updated cell.

328 A. Kassian [UF 41

SCauc. *[]VrV to speak, pray > fara-ya priest [32]

NCauc. *bV cattle-shed ~ fael house [30]

STib. *bhr abundant, numerous ~ far thousand [31]

SCauc. *br a k. of predator > pra leopard [37]

SCauc. *[

]ombi superpower > tafa-r-na lord, tawa-nanna lady [52]

Yen. *t[e]mb-V- root ~ tup root [63]

Yen. *bot- often ~ fute long (in temporal meaning) [44]

Yen. *p to cover; to plug; to close ~ tip gate [49]

STib. *Pr-V country ~ fur country; population [41]

STib. *tp (~ d-) fear, to be confused ~ tafa fear [53]

STib. *cVp (~ -) bitter, pungent ~ zipi-na sour [66]

Yen. *q[e]p (~ -) moon ~ kap moon [15]

The situation with Hatt. f / p/ w resembles the Yenisseian reexes of SCauc. labial

stops, for which see , 1982/ 2007, 149 f. Yen. *p yields p/ p

h

/ p

f

/ h in

known languages, while Yen. *b > b/ p/ v. An exact parallel to Hattic are early

records of Kottish, Arin and Pumpokol, were f, p

h

, p

f

, p and even b freely alter-

nate.

SCauc. nasal *-m- in the medial position is retained:

NCauc. *=a(m)sV to be silent, listen ~ am(a) to hear [48]

Labial m > n before a dental consonant is without doubt a late (synchronic?)

process in Hattic:

SCauc. *=VmV(r) to stand, stay > *(a)mti > (a)nti to stand [28]

But in the initial position SCauc. *m- coincides with SCauc. labial stops and

yields Hatt. f-/ p-/ w-:

SCauc. *mVjwV sour, salty > wet (fet?) sour [34]

SCauc. *mIlwV to blow; wind > pezi-l wind [35]

STib. *mVn to perceive; to think ~ pnu to look [36]

STib. *mor grain ~ fula bread [38]

SCauc. *HmoV to die, dead > fun(a) mortality [40]

STib. *mVt to eat, swallow ~ pu to devour [42]

The process of denasalization in the initial position is paralleled by the Yenis-

seian branch, where SCauc. *m- > Yen. *b-/ p-/ w- (for the distribution see SCC,

37 f.).

16

Synchronically Hattic possesses a number of stems with initial m-:

16

Roots in m-, attested in the synchronic Yen. languages, are Russian, Nenets, etc. loan-

words. The second source of m- in the Yen. languages is the late distant assimilation Yen.

*bVN- / *wVN > mVN which occurs in some auxiliary morphemes.

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 329

ma/ fa and [47], mai(u) a valuable cloth [48], malhip good, favorable

[49], mar or kamar to slit, slash [50], mael or parel cult performer,

chanter, clown

?

[51], milup or lup

??

bull, ox [52], mi to take (for oneself)

[53], mu/ fu mother, lady, mistress (vel sim.) [54], muh(al) hearth [55],

muna-muna foundation, base, bed stone [56], mu smth. relating to tree,

fruit

?

[57]. None of these roots possesses a reliable SCauc. etymology, and cul-

tural terms clearly prevail in the list, so we can threat all these words as loans. At

least for two of the mentioned stems the source of borrowing can be established:

malhip good, favorable [49] < WCauc. *ma\V good, luck (with lhip for the

palatalized labialized lateral *\); mael cult performer, chanter, clown

?

[51]

< WSem. ml (milu) cymbal player.

An interesting case is Hatt. mi to take (for oneself) [53], belonging to the

basic vocabulary. Its SCauc. cognate may be Yen. *ma() take! (the compari-

son is possible if we suppose the loss of the nal consonant in Yen. allegro

forms)an exceptional case of preserving m- in Proto-Yen.

On the other hand, Hattic possesses a few grammatical prexes in m- (for the

list see HWHT, 230 f.). This fact, however, does not contradict our theory, since

the situation, when auxiliary morphemes violate common phonotactical rules, is

not so rare in the word languages. Second, some of these prexes have variants

with initial f- (see HWHT, 165, 230 f.), the same concerns conjunction ma and

[47] and noun mu mother, lady, mistress (vel sim.) [54], which alternate with

variants fa and fu respectively (note that mu/ fu mother, lady, mistress (vel

sim.) [54] is attested only as the second element of compounds).

In addition cf. Hatt.

D

fazulla, which is probably the same deity as

D

mezulla,

known from Hittite texts (HWHT, 911 w. lit.).

SCauc. *w is generally retained in Hattic:

SCauc. *wV thou > we thou (2

nd

person sg. personal pronoun), u- thy

(2

nd

person sg. possessive pronoun) [77]

SCauc. *VwV to pour; wet > tefu to pour [57]

STib. *lw to be able ~ lu to be able [25]

SCauc. *=w to take > ku to seize [19]

In one case we see the dissimilative nasalization *-uw- > -um- (that resembles

similar phonotactical process in Hittite):

SCauc. *cjwIlV rainy season > *tuwil > tumil rain [62]

4.2.2.2 Dentals

SCauc. *t, *, *d were merged in Hatt. t (~ tt). Cf. :

SCauc. *=tV to put, leave > ti to lie, put [55]

SCauc. *dVHV to grow; big > te big [54]

330 A. Kassian [UF 41

Also with an unidentied dental :

STib. *tp (~ d-) fear, to be confused ~ tafa fear [53]

Yen. *kat (~ g-, -c) old (attr.) ~ katte king [17]

Yen. *bot- often ~ fute long in temporal meaning [44]

Yen. *t[e]mb-V- root ~ tup root [63]

An important case is Hatt. z for SCauc. dental stop:

Yen. *d()q- (~ *dk-) to fall ~ zik (< *tik) to fall [65]

It seems that /ti/ became /i/ (graphical zi) in Hattic, since the sequence ti is

relatively rare in texts known to us (in contrast to zi) and sometimes ti-forms

have by-forms in zi (e. g., tiuz ~ ziuz rock). The same assibilation /ti/ > /i/ is

observed in the reexes of SCauc. affricates, which standardly yield the stop

phoneme /t/, but affricate // before /i/, see 4.2.2.3 below. Together with the dis-

similation /u/ > /um/ this process of assibilation nds its direct parallel in the

Proto-Hittite historical phonology.

SCauc. nasal *n is a stable phoneme:

SCauc. *hVnV now > anna when [2]

SCauc. *=HVV(-n) clear (of weather) > etan sun [5]

SCauc. *xnI (-) water; wave > han sea [7]

NCauc. *=a

wVn to open ~ han to open [8]

SCauc. *=axgwV(n) to look, see > kun to see [21]

STib. *mVn to perceive; to think ~ pnu to look [36]

STib. *n to tread, trace ~ nu to come, go [29]

NCauc. *-nV, genitive ~ -n, genitive [74]

In one case we see *n > m before a labialized guttural :

NCauc. *nV woman, female > *limhu-t > nimhu-t woman [27]

SCauc. non-initial *-r- standardly yields Hatt. r:

SCauc. *Vrqw wide > harki- wide [9]

STib. *bhr abundant, numerous ~ far thousand [31]

SCauc. *[]VrV to speak, pray > fara-ya priest [32]

SCauc. *[p]r lightning; brilliance > paru bright [33]

SCauc. *br a k. of predator > pra leopard [37]

STib. *Pr-V country ~ fur country; population [41]

SCauc. *torV crust, incrustation, skin, shell > tera-h leather covering

[58]

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 331

There is one example for SCauc. *-r- > Hatt. -l-:

SCauc. *xq(w)VrV old, ripe > hel to ripen [11].

The closest analogy is Proto-Yen., were SCauc. *-r- > Yen. *r/ r

1

with unknown

distribution, while Yen. *r

1

gives l-reexes in most attested languages (-

, 1982/ 2007, 156).

Initial r- is strongly prohibited for Hattic root and auxiliary morphemes (an ex-

ception is the fossilized r-sufx, etymologically singled out in some nominal

and verbal stems). I suppose that SCauc. *r- > Hattic -.

SCauc. *rw breast, heart > aki- heart [47].

The comparison seems reliable despite the fact that the standard way to elimi-

nate initial *r- in SCauc. daughter-languages is > t-/ d-.

4.2.2.3 Alveolar, post-alveolar and palatal affricates

Reexes of SCauc. voiceless alveolar (*c, *() and palatal (*, *() affricates are

similar: Hattic stop or affricate in the initial position and Hattic sibilant -- in

other positions. This process of fricativization in the medial and nal position

runs parallel with Proto-Yen., cf., e. g., SCauc. * > Yen. *-, *s.

SCauc. voiceless alveolar affricates *c, *( yield Hatt. t- in the initial position and

Hatt. -- in other positions.

Initially:

SCauc. *cjwIlV rainy season > tumil rain [62]

SCauc. *=VV to eat, drink > tu to eat [59]

Non-initially:

SCauc. *= to put > e (~ et?) to put [4]

SCauc. *br a k. of predator > pra leopard [37]

STib. *mVt to eat, swallow ~ pu to devour [42]

SCauc. *[p]HV to blow (STib. *bt) > pu-an to blow on [43]

Some roots show Hattic z, which is in all likelihood a secondary Hittite assibi-

lation /ti/ > /i/, see 4.2.2.2 above:

NCauc. *

wV stick; timber ~ zeha-r, ziha-r wood [64]

STib. *cVp (~ -) bitter, pungent ~ zipi-na sour [66]

In one case Hatt. z-reex of SCauc. *( remains without explanation. Despite this

irregularity the comparison can hardly be rejected:

SCauc. *wjV (~ s-, ~ -I-) female > zuwa-tu wife [68]

332 A. Kassian [UF 41

The SCauc. voiceless palatal affricates *, *( yield Hatt. t~ (//) or t- in the ini-

tial position and Hatt. -- in other positions. Of course Hattic t- may cover //

here, since it is possible that spelling variants with - are merely unattested for

some morphemes.

Initially:

SCauc. *Hu earth, sand > ahhu ~ tahhu ground [45]

STib. *IH to govern; lord ~ ai-l ~ tai-l lord [46]

SCauc. *VxqV to scratch, scrape; to shave > taha-ya barber [50]

SCauc. *VwV to pour; wet > tefu to pour [57]

SCauc. *=wV (STib. *H) to take > tuh to take [60]

STib. *H to work; to build ~ teh to build [56]

SCauc. *VQV to step, run > tuk to step [61]

Non-initially:

SCauc. *xlw forelock; horn > kai horn [14]

Yen. *- (< SCauc. *() to let come, let enter ~ a to come (here) [3]

In one case a secondary Hittite assibilation /ti/ > /i/ is observed:

SCauc. *V (~ -) stone, mountain > *ti > zi mountain [67]

SCauc. voiced palatal affricate * > Hatt. t in both initial and medial positions:

SCauc. *=HVV(-n) clear (of weather) > etan sun [5]

Yen. *p to cover; to plug; to close ~ tip gate [49]

As opposed to the aforementioned affricative phonemes, the SCauc. post-alveo-

lar voiceless affricates *, *( yield Hatt. t in all positions:

SCauc. *=VmV(r) to stand, stay > *(a)mti > (a)nti to stand [28]

SCauc. *mVjwV sour, salty > wet (fet?) sour [34]

SCauc. *[

]ombi superpower > tafa-r-na lord, tawa-nanna lady [52]

In one case we see a secondary Hittite assibilation /ti/ > /i/ :

SCauc. *mIlwV to blow; wind > *peti-l > pezi-l wind [35]

4.2.2.4 Other front consonants

SCauc. *s, * are retained as Hatt. (/s/):

NCauc. *=a(m)sV to be silent, listen ~ am(a) to hear [48]

SCauc. *V (~ -) stone, mountain > zi mountain [67]

NCauc. *-:w, plural stem marker ~ a-/ i-, plural of the accusative case [70]

Yen. *a-KsV- (~ x-) temple (part of head) ~ ka head [16]

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 333

SCauc. *j was lost in the intervocalic position:

SCauc. *wjV (~ s-, ~ -I-) female > zuwa-tu wife [68]

4.2.2.5 Laterals

SCauc. lateral affricates *, *\, * merge in Hatt. l :

17

SCauc. *jV time, year, season > li year [24]

SCauc. *\npV tongue; lip; to lick > alef tongue [1]

NCauc. *bV cattle-shed ~ fael house [30]

STib. *lw to be able ~ lu to be able [25]

STib. *roH light ~ leli light [23]

One case of the occasional distant assimilation must be noted:

NCauc. *nV woman, female > *limhu-t > nimhu-t woman [27]

SCauc. *l > Hatt. l :

SCauc. *hiltw to run (away) > luizzi-l runner [26]

SCauc. *aplxqwE leaf > puluku leaves [39]

SCauc. *cjwIlV rainy season > tumil rain [62]

STib. *q(h)r to throw (into water), scatter ~ hel to strew [10]

STib. *re to dislike ~ le to envy [22]

STib. *mor grain ~ fula bread [38]

SCauc. * yields Hatt. l as well as r. Cf. similar situation in Proto-Yen., where

SCauc. * > Yen. *l ~ *r

1

~ *r with unknown distribution.

SCauc. *=gwV (*gwVV) (~ xgw-) to lose, hide > her to hide [12]

? SCauc. *VH arm, sleeve > her, hir to allocate, assign; to entrust ; to

hand over, assign; to administer [14]

SCauc. *VV (~ x-) lock, bolt > *halu bolt, lock [6]

STib. *roH light ~ leli light [23]

4.2.2.6 Velar and uvular consonants

SCauc. velar and uvular voiceless stops *k, *, *q, *q merge in Hatt. k.

Velar stops:

SCauc. *HkV to look, search > hukur to see [13]

SCauc. *rw breast, heart > aki- heart [47]

SCauc. *=w to take > ku to seize [19]

17

It is interesting but not surprising that Hattic renders lateral obstruents by lh/ lk in the

borrowings from Proto-West Caucasian: Hatt. malhip good, favorable [49] < WCauc.

*ma\V good, luck ; Hatt. hapalki iron [12] < WCauc. *I-\V iron or rather

*I-p\ copper.

334 A. Kassian [UF 41

Yen. *a-KsV- (~ x-) temple (part of head) ~ ka head [16]

Yen. *kat (~ g-, -c) old (attr.) ~ katte king [17]

Uvular stops:

SCauc. *q[]pV to cover > kip to protect [18]

SCauc. *snqV panther, leopard > take-ha lion [51]

SCauc. *Vrqw wide > harki- wide [9]

STib. *q(h)r to throw (into water), scatter ~ hel to strew [10]

SCauc. *VQV to step, run > tuk to step [61]

Yen. *d()q- (~ *dk-) to fall ~ zik to fall [65]

Yen. *q[e]p (~ -) moon ~ kap moon [15]

SCauc. velar and uvular voiceless fricatives *x, * yield Hatt. h:

SCauc. *xnI (-) water; wave > han sea [7]

NCauc. *

wV stick; timber > zeha-r, ziha-r wood [64]

NCauc. *=a

wVn to open ~ han to open [8]

SCauc. initial nasal *- > *m- > Hatt. f- (the development is exactly paralleled

by Proto-Yen.):

SCauc. *V I > fa- I, 1

st

person sg. subject [75]

In other positions SCauc. nasal * > Hatt. n:

SCauc. *HmoV die, dead > fun(a) mortality [40]

4.2.2.7 Laryngeals

SCauc. *h drops:

SCauc. *hVnV now > anna when [2]

SCauc. * standardly yields Hatt. h:

SCauc. *Vrqw wide > harki- wide [9]

NCauc. *nV woman, female > nimhu-t woman [27]

But SCauc. * drops in initial / nal clusters, see 4.2.2.13 below.

The only example of SCauc. * is:

SCauc. *br a k. of predator > pra leopard [37]

An example for SCauc. *w > 0 could be:

SCauc. *wir water, lake > ur(i) spring, well [109], if the comparison is

correct.

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 335

SCauc. *H (an unidentied laryngeal) > Hatt. h:

SCauc. *HkV to look, search > hukur to see [13]

SCauc. *Hu earth, sand > ahhu ~ tahhu ground [45]

STib. *H to work; to build ~ teh to build [56]

SCauc. *=wV (STib. *H) to take > tuh to take [60]

SCauc. *H (an unidentied laryngeal) > Hatt. 0:

SCauc. *=HVV(-n) clear (of weather) > etan sun [5]

SCauc. *dVHV to grow; big > te big [54]

STib. *IH to govern; lord ~ ai-l ~ tai-l lord [46]

SCauc. *HmoV to die, dead > fun mortality [40]

4.2.2.8 Clusters with *w

SCauc. labialized consonants (treated as Cw-clusters by S. Starostin) lose the la-

bial element in Hattic. They yield reexes which coincide with their non-labial-

ized counterparts:

SCauc. *xlw forelock; horn > kai horn [14]

SCauc. *mVjwV sour, salty > wet (fet?) sour [34]

SCauc. *mIlwV to blow; wind > pezi-l wind [35]

NCauc. *

wV stick; timber ~ zeha-r, ziha-r wood [64]

SCauc. *wjV (~ s-, ~ -I-) female > zuwa-tu wife [68]

SCauc. *hiltw to run (away) >

L

luizzi-l runner [26]

NCauc. *-:w, plural stem marker ~ a-/ i-, plural of the accusative case [70]

The same with velars/ uvulars:

SCauc. *rw breast, heart > aki- heart [47]

SCauc. *Vrqw wide > harki- wide [9]

NCauc. *=a

wVn to open ~ han to open [8]

STib. *q(h)r to throw (into water), scatter ~ hel to strew [10]

SCauc. *=gwV (*gwVV) (~ xgw-) to lose, hide > her to hide [12]

In a few cases Hattic shows unmotivated u-vocalism:

SCauc. *=axgwV(n) to look, see > kun to see [21]

SCauc. *Hxqw to preserve, guard > (a)ku escort [20]

SCauc. *aplxqwE leaf > puluku leaves [39]

Of course one can try to explain it by the inuence of an old labialized conso-

nant. As a matter of fact ve examples above, where labialized velars/ uvulars

completely lose their labial element without vowel change, speak against such a

supposition.

336 A. Kassian [UF 41

4.2.2.9 xK(w)-clusters

SCauc. clusters of the type *xK(w) (where Kvelar/ uvular) yield Hatt. k or h

without evident rule of distribution.

SCauc. *xgw > Hatt. h, k:

SCauc. *=gwV (*gwVV) (~ xgw-) to lose, hide > her to hide [12]

SCauc. *=axgwV(n) to look, see > kun to see [21]

SCauc. *x > Hatt. h, k:

SCauc. *VV (~ x-) lock, bolt > *halu bolt, lock [6]

SCauc. *xlw forelock; horn > kai horn [14]

SCauc. *xq > Hatt. h:

SCauc. *VxqV to scratch, scrape; to shave > taha-ya barber [50]

SCauc. *xqw > Hatt. k:

SCauc. *Hxqw to preserve, guard > (a)ku escort [20]

SCauc. *xq > Hatt. h:

SCauc. *xq(w)VrV old, ripe > hel, hil to ripen [11]

SCauc. *xqw > Hatt. k:

SCauc. *aplxqwE leaf > puluku leaves [39]

4.2.2.10 ST-clusters

SCauc. clusters of the ST-type yield Hatt. t, that coincides with the Proto-Yen.

reex (SCauc. *ST > Yen. *t).

SCauc. *s :

SCauc. *snqV panther, leopard > take-ha lion [51]

SCauc. *t :

SCauc. *torV crust, incrustation, skin, shell > tera-h leather covering

[58]

SCauc. *tw (with a secondary Hittite assibilation /ti/ > /i/):

SCauc. *hiltw to run (away) > *luiti-l > luizzi-l runner [26]

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 337

4.2.2.11 lC- and rC-clusters

SCauc. *l is dropped in combination with post-alveolar and palatal affricates

(this process is normal for all SCauc. branches except NCauc., SCC, 87 f.):

SCauc. *mIlwV to blow; wind > pezi-l wind [35]

SCauc. *xlw forelock; horn > kai horn [14]

For r in combination with *( see comm. on p(a)ra leopard [37] (< SCauc.

*br a k. of predator).

Quite surprising is the fact of retention of SCauc. *l and *r in combinations with

velar/ uvular (note that all SCauc. branches except NCauc. standardly lose the

sonorant in such clusters).

SCauc. *aplxqwE leaf > puluku leaves [39]

SCauc. *Vrqw wide > harki- wide [9]

In combination with * SCauc. *l is retained:

SCauc. *cjwIlV rainy season > tumil rain [62]

But SCauc. * is lost in combination with some unidentied laryngeal :

SCauc. *Hu earth, sand > ahhu ~ tahhu ground [45]

Such a development is paralleled by STib., where SCauc. *, * > *, * >

STib. *0 (SCC, 19, 191). Note that Yen. has regular *r/ r

1

< SCauc. *lH/ H

(SCC, 84).

4.2.2.12 NC-clusters

SCauc. nasal drops in combination with labial :

SCauc. *\npV tongue; lip; to lick > alef tongue [1]

SCauc. *[

]ombi superpower > tafa-r-na lord, tawa-nanna lady [52]

Yen. *t[e]mb-V- root ~ tup root [63]

Such a simplication is standard for all SCauc. branches except NCauc., but

there is a signicant number of examples, where Yen., STib. and Burush. retain

the nasal, see SCC, 39 ff., 48 ff.

Combination with post-alveolar affricate *m( > *mt > *nt :

SCauc. *=VmV(r) to stand, stay > *(a)mti > (a)nti to stand [28]

Note that the retention of the nasal in such a position is not typical of SCauc.

languages.

338 A. Kassian [UF 41

In combination with guttural the nasal drops (a standard development in SCauc.

branches except NCauc.):

SCauc. *snqV panther, leopard > take-ha lion [51]

In combination with * Hattic retains the SCauc. nasal :

SCauc. *xnI (-) water; wave > han sea [7]

NCauc. *nV woman, female > nimhu-t woman [27]

4.2.2.13 Clusters with laryngeals

In the initial and nal positions Hattic loses laryngeals in clusters:

SCauc. *mVjwV sour, salty > wet (fet?) sour [34]

SCauc. *torV crust, incrustation, skin, shell > tera-h leather covering

[58]

SCauc. *br a k. of predator > pra leopard [37]

SCauc. *HmoV to die, dead > fun mortality [40]

SCauc. *cjwIlV rainy season > tumil rain [62]

SCauc. *xnI (-) water; wave > han sea [7]

In the medial position laryngeals can be retained:

NCauc. *nV woman, female > nimhu-t woman [27]

SCauc. *Hu earth, sand > ahhu ~ tahhu ground [45]

4.3 Root structure

For the general discussion see SCC, 1 ff. The standard shape of SCauc. nominal

root was CVCV (where C can be a cluster). Normally Hattic retains this structure

as CVCV or CVC (with unknown rules of the nal vowel drop). Cf. the follow-

ing selective examples.

CVCV:

SCauc. *rw breast, heart > aki- heart [47].

SCauc. *VV (~ x-) lock, bolt > *halu bolt, lock [6]

SCauc. *[p]r lightning; brilliance > paru bright [33]

SCauc. *torV crust, incrustation, skin, shell > tera-h leather covering

[58]

CVC:

SCauc. *xnI (-) water; wave > han sea [7]

SCauc. *xlw forelock; horn > kai horn [14]

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 339

The situation with SCauc. verbal roots is more complicated, since the actual

SCauc. reconstruction in general is NCauc.-centric, but it is clear that the struc-

ture of some types of verbal roots was seriously rebuilt in the Proto-NCauc. lan-

guage.

I suppose that the main SCauc. verbal shapes were:

CVCV

CVC

VCV(R)

CV

where C can be an obstruent, a sonorant or a consonant cluster. Very often

NCauc. (or rather its ECauc. sub-branch?) adds an initial =V- or =HV-, which

serves as a spacer between ECauc. class exponents (=) and root. In most cases

S. Starostin projects such a spacer onto the Proto-SCauc. level (e. g., he ac-

cepts SCauc. *=VCVR instead of *CVR). Since the reconstruction of NCauc.

and SCauc. morphosyntax is the task of futher research and is not a goal of my

paper, I adopt Starostins reconstructions of individual roots. It should be noted

that Hattic does not show traces of these =V-/ =HV- spacers, thus conforming

in it with the STib., Yen., Burushaski and Basque branches.

Standardly Hattic retains the shape of SCauc. verbal proto-roots, but some-

times in a polysyllabic structure a nal vowel may have been lost (as in the case

of nominal roots the rules of a nal vowel drop are not clear).

SCauc. CVCV > Hatt. CVCV:

SCauc. *HkV to look, search > NCauc. *H[o]kV ~ STib. *ku ~ Yen. *b-

[o]k- ~ Hatt. huku-r to see [13]

SCauc. *[]VrV to speak, pray > STib. *p(r)IwH ~ Yen. *ba- ~ Burush.

*bar ~ Hatt. fara-ya priest [32]

SCauc. *VxqV to scratch, scrape; to shave > NCauc. *VqV ~ Yen.

*[e]()V ~ Hatt. taha-ya barber [50]

SCauc. *VwV to pour; wet > NCauc. *=w ~ STib. *w ~ Burush.

*ao ~ Hatt. tefu to pour [57]

SCauc. CVCV > Hatt. CVC:

SCauc. *xq(w)VrV old, ripe > NCauc. *=rqw to ripen ~ STib. *gr

old, large ~ Hatt. hel to grow, ripen [11]

SCauc. *q[]pV to cover > STib. *Gp ~ Yen. *qepVn- ~ Hatt. kip to pro-

tect [18]

SCauc. *VQV to step, run > STib. *ek ~ Yen. *q- ~ Hatt. tuk to

step [61]

340 A. Kassian [UF 41

SCauc. =V-CVR > Hatt. CVR:

NCauc. *=a

wVn to open ~ Hatt. han to open [8]

SCauc. *=gwV (*gwVV) (~ xgw-) to lose, hide > NCauc. *=igwV ~

STib. *koj (~ -l) ~ Basque *gal- ~ Hatt. her to hide [12]

SCauc. *=w to take > NCauc. *=w ~ STib. *Khu ~ Hatt. ku to

seize to seize [19]

SCauc. *=axgwV(n) to look, see > NCauc. *=agwV ~ STib. *kn ~ Yen.

*qo ~ Hatt. kun to see [21]

SCauc. VCV > Hatt. VCV:

SCauc. *=VmV(r) to stand, stay > NCauc. *=Vm

Vr ~ STib. *hi-oH ~

Hatt. (a)nti to stand, stay [28]

SCauc. VCV > Hatt. VC:

SCauc. *= to put > NCauc. *=i ~ Yen. *es- ~ Basque *ecan ~ Hatt.

e to put [4]

SCauc. =V-CV > Hatt. CV:

SCauc. *=tV to put, leave > NCauc. *=tV-r ~ STib. *dhH ~ Yen. *di(j)

~ Hatt. ti to lie, put [55]

SCauc. *=VV to eat, drink > NCauc. *=V

V ~ STib. *ha-H ~ Yen. *s- ~

Burush. *i / *i / *u ~ Hatt. tu to eat [59]

5 HatticSino-Caucasian root comparisons

Entries are arranged in the following alphabetic order: a, e/ i, h, k, l, m, n, f/ p/ w,

/ s, t, u, z. The numeration in section 5.1 (reliable root comparisons) is contin-

ued in section 6.1 (reliable grammatical comparisons). The same concerns the

numeration with character stroke () in section 5.2 (dubious root comparisons),

which is continued in 6.2 (dubious grammatical comparisons). The entries have

the following structure:

No. Hattic data.

= Hittite equivalent in bilingual or quasi-bilingual texts.

Proposed Sino-Caucasian etymology.

Comments and references.

5.1 Roots with reliable SCauc. cognates

1. alef (alep, alip, aliw) tongue; word; to say

?

= Hitt. EME.

SCauc. *\npV tongue; lip; to lick >

2009] Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian Language 341

NCauc. *\npV lip > Tsez. *\ipu (~ --, - -), Lezgh. *\amp- (~ -).

STib. *ep tongue, to lick > Tib. gab to lick, Kachin (H) i-lep

tongue.

Yen. *alVp (~ --, -r

1

-, -b) tongue > Kott. alup, Arin ap, elep.

Yen. *a- (a former class-prex?) exactly matches the Hattic onset. The Hat-

tic meaning corresponds to Yen. and STib. as opposed to NCauc.

Similarly , 1985, 1 (Hatt. + Yen.). Untenably , 1994, 21

(Hatt. + WCauc. *(a):V word, speech; to say; to swear).

2. anna when, sobald, als

= Hitt. mn.

SCauc. *hVnV now >

NCauc. *h[]nV now > Nakh *hin-ca/ *hin-a now, Tsez. *hin-V to-

day, Dargwa *han- now, Lezgh. *hin- now, WCauc. *n- today; cf.

Hurr. henni, Urart. hini now.

STib. *n[] time or place of, when > Chin. *n particle by verbalizing,

as, and yet, and (?), Tib. na year(?); stage of life, age; when, Kachin

(H) na, na to extend in time, na loc. or abl. sufx, Lushai nia at the

time of; when, -na the place of or where, instrument of or for.

Yen. *en now > Ket n, Yug en. The Ablaut form *an- in compounds >

Yug an-es

5,6

morning (an- + God, sky), an-bks

5

tomorrow = Ket

ank

5,6

tomorrow (an- + *pVk- morning); apparently the basic mean-

ing of an- in the compounds listed is when, not now. *en-a > Kott.

eaa now, Arin ini today.

Double nn in the Hattic form may point to an old cluster. If so, Yen. *en-a

appears the closest parallel (* > n seems regular for Hattic), despite se-

mantic difference and vocalic alternation.

, 1985, 2 compares Hattic anna with some WCauc. adverbial / pro-

nominal forms of the shape an-, covering a large spectrum of demon-