Professional Documents

Culture Documents

An Evaluation of The Direct Instruction Program

Uploaded by

Red KhOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

An Evaluation of The Direct Instruction Program

Uploaded by

Red KhCopyright:

Available Formats

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

An Evaluation of the Direct Instruction Program Kecia L. Addison Mary E. Yakimowski

Direct Instruction was first implemented as a reform model in 1996-97 at selected schools in the Baltimore City Public School System (BCPSS) to increase student reading achievement. Currently, there are 16 schools implementing Direct Instruction with 13 receiving Title I funding. This program evaluation report is in response to the request of Ms. Carmen Russo, Chief Executive Officer, to assess the impact of this program with a particular focus on student achievement outcomes.

Background Information Direct Instruction is a teaching model created by Siegfried Engelmann and Wesley Becker that relies upon highly scripted lesson plans, frequent auditory and visual response signals, repeated checks for mastery, and constant acknowledgement and interaction between teacher and student. Direct Instruction is based on the premise that learning can be accelerated when clear instruction eliminates misinterpretation (American Institutes of Research, 1999). According to Parson and Polson (2002), features of Direct Instruction include: small student groupings based on instructional levels or homogeneity, scripted lesson plans, rapid pace delivery, teacher focus, immediate feedback and correction, and teacher cued responses from students. Other features mentioned are research-based curricula, in-class coaches, and frequent assessments

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

(American Federation of Teachers, 2002). Ligas (2002) states the purpose of Direct Instruction is to increase learning by systematically developing background knowledge, helping students learn to apply that knowledge, and linking it to new knowledge. Some educators laud Direct Instruction as very effective while others deem it rigid (Viadero, 1999). Direct Instruction has been frequently noted as one of three highly recommended, research- based models of instruction for elementary school-aged students. A national evaluation on the impact of Direct Instruction revealed significant positive effects at sites where Direct Instruction was provided for both three and four years (Stebbins, St. Pierre, Proper, Anderson, & Cerva, 1977). Students in 60% of these studies receiving Direct Instruction performed higher for total reading. Performance on reading achievement tests was also found to be higher for students in the four-year program than those in the three-year program (Becker & Gersten, 2001). Yet, it is important to note that student achievement success can vary depending on the component of the Direct Instruction approach being measured (e.g., pacing, format, correcting students) (Direct Instruction, n.d.). The Baltimore City Public School System originally used Direct Instruction as an alternative instructional strategy, but over time it has been employed as a method of addressing school improvement. With 16 schools currently implementing some form of Direct Instruction most receiving Title I funding and some having used the program for up to six years it has become important to assess the programs overall effectiveness. This examination comes at a promising time, as education research and federal funding continue to move strongly in the direction of comprehensive school reform. The examination is also relevant in light of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, which requires that instructional practices be based on scientifically-based research programs with proven results in Title I schools. Review of the Literature We provide in this section of the report an overview on the current state of knowledge on Direct Instruction and its practical application. Literature included was selected based on relevance to the objective of investigating of Direct Instruction as a strategy for increasing student achievement, with a special focus on reading.

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

History and Development More than 30 years ago, Bereiter and Engelmann (1966) posited a theory that all students can experience success and that the failure of some students to succeed should direct attention to instruction not students (Becker, 1971, p. 402). Rooted in Bereiter and Engelmanns experimental preschool and Beckers behavioral research on classroom management, the Direct Instruction model was developed. According to Becker and Gersten (2001), the model represents a highly structured approach to early-childhood education with an emphasis on high levels of academic engaged time through small-group instruction in reading, oral language, and arithmetic (p. 58). Its major goal is to improve the fundamental education of children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds in order to increase options later in their life (Becker, 2001). Direct Instruction as a program, actually a series of programs, originated during Project Follow Through, a compensatory education program founded under President Lyndon B. Johnson. Direct Instruction, instituted in 1967, was designed to help break the cycle of poverty through improved education and thus greater employment options. Direct Instruction was originally known as DISTAR (Direct Instruction System for Teaching Arithmetic and Reading) and focused on reading and mathematics for students in grades K-3. DISTAR was based on Engelmanns research on reading instruction and the assumption that the teacher is largely responsible for how well students learn (Adams & Engelmann, 1996). Direct Instruction differed from Project Follow Through models, however, with its highly structured, step-by-step curriculum and a well-developed system for providing teachers with remedies to specific problems (Gersten & Keating, 1987). The early version of Direct Instruction has since been expanded to reach students in PreK through grade 6 and now includes U.S. History, writing, reasoning, and spelling, in addition to reading and mathematics. Theoretical Foundation Engelmann and Carnines (1991) theoretical framework for Direct Instruction asserts that faultless communication by the teacher leads to effective understanding by students. A faultless presentation rules out the possibility that the learners inability to respond appropriately to the presentation, or to generalize in the predicted way, is caused by a flawed communication rather than by learner characteristics (Engelmann & Carnine, 1991, p. 3).

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

Students learn more if instructional presentations are clear, which rules out misinterpretations and helps students generalize skills in different contexts (EdWeek, 3/17/99). Engelmanns research also included pinpointing where students make mistakes and how to avoid them. Direct Instruction incorporates a theory of learning called Mastery Learning whereby teachers help students master basic academic skills before moving on to more complex cognitive activities. Benjamin Bloom (1987), who developed Mastery Learning in the 1960s, believed that all children could learn given the right circumstances, but the rate of learning differs from child to child. In Mastery Learning, the teacher directs a variety of group-based instructional techniques, providing frequent and specific feedback using diagnostic and formative tests, as well as systematically correcting the mistakes students make. The theory of Mastery Learning is incorporated within Direct Instruction through the use of scripted lesson plans. Scripted lesson plans provide consistent teacher vocabulary, which has been reported to improve understanding and build word knowledge. One of the leading obstacles cited by some (e.g., Biemiller, 2001; Hart & Risely, 1995 as cited in Berkeley, 2002) to academic achievement in disadvantaged children is a lack of adequate vocabulary skills for academic pursuits. Engelmann further claims that it takes teachers two years to develop a comfort level with the Mastery Learning aspects of Direct Instruction and teach the program well (EdWeek 3/17/99). Original Project Follow Through Numerous studies have been conducted using the original Project Follow Through data, following students over time to determine the long-term impact of the program on achievement scores and academic performance. Abt Associates found that the original Direct Instruction model produced higher gains in achievement than 13 other models studied (Becker & Engelmann, 1995; Adams & Engelmann, 1996). This was true especially for academic skills gained in mathematics, reading comprehension, and language (Stebbins, St. Pierre, Proper, Anderson, & Cerva, 1977, as cited in Gersten & Keating, 1987). Gersten and Keating (1987) conducted a longitudinal study in the early 1980s on high school graduates who had received Direct Instruction at the elementary grade levels from Project Follow Through. In the four communities studied, Direct Instruction consistently produced positive results in all areas of academic achievement. The impact was even stronger in students

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

who had received the intervention earlier, such as in kindergarten rather than in first grade. The amount of time students spent in Direct Instruction schools and the amount of time a teacher spent teaching Direct Instruction positively correlated to increased student achievement. Research has also shown that students exposed to the Direct Instruction program for four years, as opposed to three years, experienced considerably higher achievement gains. However, some of the studies that used Project Follow Through data are more than 10 years old and are criticized for being invalid with regard to todays classrooms. Recent Studies As of 1999, 150 schools across the country have implemented Direct Instruction as part of a comprehensive school reform (American Institutes of Research, 1999). Meyer (1984) contends that students who spend two years in Direct Instruction classrooms are less likely to drop out or be assigned to special education classrooms. According to the National Institute for Direct Instruction (NIFDI) a major provider of Direct Instruction implementation assistance the most significant improvement in standardized test performance is realized in the third year of implementation. National Institute for Direct Instruction (NIFDI) also reports that students who experience Direct Instruction in kindergarten and continue beyond the second grade experience the greatest gains in achievement (NIFDI, 2002). Adams and Engelmann (1996) conducted a meta-analysis of 37 research studies performed on Direct Instruction. They found that Direct Instruction works with different types of students, produces positive achievement benefits in each of the subjects studied (i.e., reading, language, mathematics, and spelling), and even has a positive impact on students self-esteem. They note, however, that the extent to which schools implement the program correctly is critical to its success. Central to this is teacher preparedness and comfort with Direct Instruction teaching. In 1999, the American Institutes of Research released a study stating that Direct Instruction was one of only three (out of 24 analyzed) school reform programs with a strong record of evidence of positive effects on student achievement (AIR, 1999). 1 As part of the study, AIR found 14 studies of Direct Instruction that met their standards for scientific rigor. Of those 14 studies, seven found gains in reading, 11 in mathematics, and nine in language (AIR, 1999).

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

Despite the positive findings by these researchers, some question whether Direct Instruction adequately prepares students to continue their education in environments not incorporating this model. In some cases, the positive effects dissipate when students leave the Direct Instruction structure (Gersten and Keating, 1987). Researchers point to the possibility that Direct Instruction 1 A finding of strong positive effects on student achievement means that four or more studies, using rigorous methodologies, show some positive effect on student achievement. At least three of those studies must show effects that are educationally or statistically significant (AIR, 1999). students are babied through sequences that have made instruction easy for them, causing potential trouble later in non-Direct Instruction environments. Becker and Gersten (1982), conducting a follow-up study at Direct Instruction sites, found that after leaving the Direct Instruction program in grade 3, students achievement scores declined (Adams & Engelmann, 1996). However, as a result of these findings, more Direct Instruction programs were added to carry students through grade 6. Critics further indicate that Direct Instruction may impose a stifling structure that limits teacher and student creativity and may produce negative social side affects. In a comparison of three preschool programs, Schweinhart and Weikart (1997), found that although the achievement gains in Direct Instruction were undeniable, it could also cause negative side effects later in life. The study followed poor children who had been randomly assigned to one of three preschool classrooms, one of which employed Direct Instruction. All three programs produced academic gains, with the Direct Instruction students scoring better than the other two groups. However, in this one study, at age 15, more Direct Instruction students (46%) had emotional problems, and by age 23 the Direct Instruction students had higher rates of felony arrests than the students from the other programs. Direct Instruction proponents challenge the reliability of the sample, since there were only 68 students. More specifically, in a response to the article written by Schweinhart and Weikart (1997), Engelmann (1999) questions their attempts at establishing statistical significance between the preschool programs. Engelmanns (1999) biggest complaint is that the authors do not provide the data to support the issue of preschool experiences as they relate to felony behavior. He cites that there are too many intervening influences, too many

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

differences between the groups and their experiences to single out the preschool as the cause for differences in felonies (p. 23). Stodolsky (1988) further points to Goodlads (1984) research on the qualities of schooling, which expresses concern about the Direct Instruction model. Goodlad (1984) studied elementary schools and found an overemphasis on factual knowledge, a neglect of creativity, a lack of meaningful inquiry, and a curriculum that lacked in complexity. Stodolsky (1988) asserts that the Direct Instruction model suffers many of the deficiencies cited by Goodlad (1984). Studies in Urban Settings Direct Instruction has been implemented in a number of urban communities, including Houston, Fort Worth, Broward County, Sacramento, and Baltimore City. The model was found to have had a positive impact on reading achievement as shown in longitudinal research studies of these urban areas conducted in the late 1990s. Though Direct Instruction has produced positive findings, some question its effectiveness over other curriculum programs in situations where students perform equally as well without the implementation of a reform model or systematic implementation of a designated program. In Houston, 20 schools used a program modeled after Direct Instruction known as the Rodeo Institute for Teacher Excellence (RITE) in 2001. Researchers (Carlson & Francis, 2002) found that RITE was successful in accelerating students development of pre-reading and reading skills in at- risk schools. These researchers compared Direct Instruction students in grades K-2 with a control group of students who did not receive the program. Students in the program the longest experienced the largest gains in reading achievement. Using Texas Assessment of Academic Skills passing rates, 82% of grade 3 students who were in RITE for three years passed, compared to 73% for students in RITE for one year. The comparison groups passing rates were 68% and 65%, respectively. Further, gains were the most dramatic in the first two years of schooling, particularly for students who began the program in kindergarten. Researchers in Fort Worth, Texas, found that Direct Instruction had a positive impact on student reading achievement, especially in disadvantaged students in kindergarten. In Fort Worth, Direct Instruction was used for pre-reading and early reading skills in kindergarten, and grades 1 and 2 for more than 14,000 students in 61 elementary schools. Researchers compared performance on standardized tests with prior year performance and national norms (OBrien & Ware, 2002).

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

In Broward County, Florida, Direct Instruction was linked to student success; however, because Direct Instruction was only a part of the total curriculum program, its impact on reading achievement could not be accurately determined. The fifth-year evaluation of the Broward County Alliance of Quality Schools Project concluded that the impact of a hybrid program (which combined Direct Instruction with Accelerated Reader and Computer Assisted Instruction) on student achievement in reading varied across grade levels. The study found that students in grade 4 experienced the largest reading achievement gains. Their normal curve equivalent score gain was 7.8, compared to their district counterparts who gained 6.6 (Ligas, 2002). Findings from a research study in Sacramento (Grossen, 2002) showed that a model based on Direct Instruction, known as the BIG Accommodation Model, had a positive impact on at-risk students in low-achieving secondary schools in both language arts and mathematics. The BIG Accommodation Model, which has been described as a new generation Direct Instruction program organized around big ideas, was successful for all racial and ethnic groups, English language learners, and for students performing at all levels. On pre- and post-tests of reading performance, all racial/ethnic groups experienced gains of at least 1.2 percentile points. In Baltimore City, university researchers MacIver and Kemper (2002), conducting a comprehensive study, found Direct Instruction to have had a positive impact on student achievement, but also said that questions remain as to whether Direct Instruction students are doing significantly better than students who are receiving other types of instruction, even when the students begin Direct Instruction in kindergarten. Six of the 16 Direct Instruction schools, five of which had free or reduced-price lunch rates of 80% or higher, were compared to demographically similar schools in the city. In both the Direct Instruction and comparison groups, two cohorts comprised of students who were either in kindergarten or second grade in 1996-97 were followed. Through classroom observations, interviews, focus groups, and achievement test scores, the researchers found mixed results. While there was evidence of a positive impact on vocabulary test scores and measures of oral reading fluency, there was no compelling evidence as to a significant effect of Direct Instruction on reading comprehension (MacIver & Kemper, 2002, p. 215 - 217).

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

Also in Baltimore City, as part of the comprehensive evaluation (2001) of the full City-State partnership, Westat looked at the effectiveness of two of the citys reform models. Though limited in the depth of analysis conducted in this particular area, analyses did show that Direct Instruction had been beneficial but that it is time to take a hard look at the extent to which the current models are meeting BCPSS needs and are reflective of what is known about best practices in instruction (Westat, 2001, p. xii). During site visits, staff recognized the positive effect that Direct Instruction has had on students reading levels, particularly at the lower grades. However, some staff questioned its utility at the higher grade levels, and some did not feel that these students were prepared for traditional instruction (Westat, 2001, p. xii). In a study of four models of school improvement, Borman, Rachuba, Datnow, Alberg, MacIver, Stringfield, and Ross (2000), looked at a Direct Instruction-hybrid program administered at two urban schools characterized by high levels of free-lunch eligibility and a predominately African American student population. The Direct Instruction program was mixed with Core Knowledge, a program developed by E. D. Hirsch that specifies content areas but not instructional methods. At one school, principal and teacher perceptions of the program improved over time as staff members became more comfortable with the program. However, at the other school, the principal was concerned that there was too much variability in how teachers taught the lessons. Some teachers criticized the scripted nature of Direct Instruction and the lack of professional development activities. Achievement data measured by test scores showed mixed results. At one school, the reading and mathematics scores of students in grade 2 remained the same or increased slightly (i.e., one and three percentage points respectively); whereas at the other school, scores increased more substantially with reading scores increasing 19 percentage points and mathematics increasing 11 percentage points. Despite its critics, however, the literature reflects significant interest in Direct Instruction. As Direct Instruction has evolved over the years, it has been used to address particular niche needs, specifically those of at-risk students in urban settings. The next section describes the mechanics of Direct Instruction, which will later be described with specific reference to BCPSS. Finally, teachers responded to a question about the impact of Direct Instruction on student behavior. Again, the results are presented by years of overall teaching experience, as

Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment, and Accountability

Direct Instruction

developed by the Baltimore Curriculum Project staff. Teachers at the original six schools believed more consistently that Direct Instruction improved or maintained student behavior. At the other schools, at least 80% of the teachers responded positively about Direct Instruction improving or maintaining student behavior.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- National Emergency Medicine Board Review CourseDocument1 pageNational Emergency Medicine Board Review CourseJayaraj Mymbilly BalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Week1module-1 Exemplar Math 7Document5 pagesWeek1module-1 Exemplar Math 7Myka Francisco100% (1)

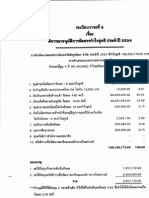

- ตารางDocument1 pageตารางRed KhNo ratings yet

- งบกำไรขาดทุนของสหกรณ์Document1 pageงบกำไรขาดทุนของสหกรณ์Red KhNo ratings yet

- รายได้จากการลงทุนฉลากกินแบ่งรัฐบาลDocument1 pageรายได้จากการลงทุนฉลากกินแบ่งรัฐบาลRed KhNo ratings yet

- L$Ioulri: I TLTD RdcutjtiiorlrnrdDocument1 pageL$Ioulri: I TLTD RdcutjtiiorlrnrdRed KhNo ratings yet

- Academic Acceleration G1 TR 2007-1Document34 pagesAcademic Acceleration G1 TR 2007-1Red KhNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Teaching Communication in Dental Education. A Survey Amongst Dentists, Students and PatientsDocument6 pagesThe Importance of Teaching Communication in Dental Education. A Survey Amongst Dentists, Students and Patientsandres castroNo ratings yet

- Sociolgy of Literature StudyDocument231 pagesSociolgy of Literature StudySugeng Itchi AlordNo ratings yet

- IITH Staff Recruitment NF 9 Detailed Advertisement 11-09-2021Document14 pagesIITH Staff Recruitment NF 9 Detailed Advertisement 11-09-2021junglee fellowNo ratings yet

- Magic Mirror American English Teacher Ver2Document7 pagesMagic Mirror American English Teacher Ver2COORDENAÇÃO FISK CAXIASNo ratings yet

- IManager U2000 Single-Server System Software Installation and Commissioning Guide (Windows 7) V1.0Document116 pagesIManager U2000 Single-Server System Software Installation and Commissioning Guide (Windows 7) V1.0dersaebaNo ratings yet

- IPCR Portfolio MOVs TrackerDocument10 pagesIPCR Portfolio MOVs TrackerKris Tel Delapeña ParasNo ratings yet

- FreeLandformsBulletinBoardPostersandMatchingActivity PDFDocument28 pagesFreeLandformsBulletinBoardPostersandMatchingActivity PDFDharani JagadeeshNo ratings yet

- Module 7Document4 pagesModule 7trishia marie monteraNo ratings yet

- CSC)会提交 MOE)及国家留学基金管理委员会(CSC)Document10 pagesCSC)会提交 MOE)及国家留学基金管理委员会(CSC)WARIS KHANNo ratings yet

- Elementary English Review 4 Units 28 35 British English StudentDocument8 pagesElementary English Review 4 Units 28 35 British English StudentSamuel RuibascikiNo ratings yet

- Drohvalenko - Ea - 2021 - First Finding of Triploid in Mozh RiverDocument7 pagesDrohvalenko - Ea - 2021 - First Finding of Triploid in Mozh RiverErlkonigNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship ReportDocument25 pagesSummer Internship ReportPrateek YadavNo ratings yet

- Behaviorally Anchored Rating ScalesDocument6 pagesBehaviorally Anchored Rating Scalesmanoj2828No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan For Math 1Document6 pagesLesson Plan For Math 1Mary ChemlyNo ratings yet

- Sizanani Mentor Ship ProgramDocument2 pagesSizanani Mentor Ship ProgramsebafsudNo ratings yet

- Attendance Monitoring System and Information Dissemination With Sms Dissemination"Document4 pagesAttendance Monitoring System and Information Dissemination With Sms Dissemination"Emmanuel Baccaray100% (1)

- VMGODocument1 pageVMGOJENY ROSE QUIROGNo ratings yet

- Lab#7 Lab#8Document2 pagesLab#7 Lab#8F219135 Ahmad ShayanNo ratings yet

- B2016 Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Expectancies, Trusz ROUTLEDGEDocument203 pagesB2016 Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Expectancies, Trusz ROUTLEDGEricNo ratings yet

- Video Classroom Observation FormDocument4 pagesVideo Classroom Observation FormPhil ChappellNo ratings yet

- CNP 4Document22 pagesCNP 4Aregahagn NesruNo ratings yet

- BIE Prospective Students BrochureDocument5 pagesBIE Prospective Students BrochureparvezhosenNo ratings yet

- An Analysis Between The Outcome Based Curriculum and Standard Based Curriculum in Papua New Guinea - 113538Document5 pagesAn Analysis Between The Outcome Based Curriculum and Standard Based Curriculum in Papua New Guinea - 113538timothydavid874No ratings yet

- Original PDF Management by Christopher P Neck PDFDocument41 pagesOriginal PDF Management by Christopher P Neck PDFvan.weidert217100% (35)

- Study and Evaluation Scheme For Diploma Programe in Sixth Semester (Civil Engineering)Document2 pagesStudy and Evaluation Scheme For Diploma Programe in Sixth Semester (Civil Engineering)AlphabetNo ratings yet

- Handwritten Digit Recognition Using Image ProcessingDocument2 pagesHandwritten Digit Recognition Using Image ProcessingBilal ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- UPS 04 (BI) - Application For Appointment On Contract Basis For Academic StaffDocument6 pagesUPS 04 (BI) - Application For Appointment On Contract Basis For Academic Staffkhairul danialNo ratings yet

- Site Directed MutagenesisDocument22 pagesSite Directed MutagenesisARUN KUMARNo ratings yet