Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Policy

Uploaded by

Jonathan JacobsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Policy

Uploaded by

Jonathan JacobsCopyright:

Available Formats

Jonathan Jacobs The Gamble: General David Petraeus and the American Military Adventure in Iraq, 2006-2008, Chapter

4 Afterward November 28th, 2010 Thomas Ricks presents a detailed account of the radical shift in US military and political policy in Iraq following three years of failure. Ricks describes how the military and political establishment finally heeded the warnings of disaster that were ignored from 2003 onward, making radical and unexpected changes in its Iraq war approach. The success of the surge, beginning in 2007, can be attributed to the following factors: new leadership at the top, an increase in local knowledge, the elimination of structural secrecy, and the end of mirror imaging. However, even with the turnaround, the surge presented policy mistakes and dangers. These included short term gains coupled with long term losses, an inability to translate military victory into political gain, and a variant of mission creep. By analyzing the implementation of the surge in the Iraqi war, the reader can learn about successful policy decisions and strategies and what institutional failures continued to impede full success. Throughout the narrative Ricks presents specific changes made at the intuitional level of the military operation which were in direct juxtaposition to how the military functioned prior to the first three years of the war operation. One major change was the appointment of General Petraeus in 2007 to command the coalition forces in Iraq. With that selection, the Bush administration was turning the war over to the opposition inside the US military (128). Bushs previous selections for the political and military voices of the administration were those who had a strong hawkish opinion of the war in Iraq. Their inherent conformation bias led to a disregard for any criticism of the war planning. By appointing those who have warned of tail risk, the worst possible consequences of an event, a disaster is more likely to be averted or corrected. As Ricks writes in the afterword of the narrative, One of the causes of catastrophic failuressometimes is a lack of imagination in assessing a situation (314-315). By promoting individuals who had been pessimistic about the administrations policy, the military was set for greater success. Once appointed, Petraeus made two major decisions which helped turn the war effort around. First, Petraeus was able to work with and appoint people who disagreed wit him from both inside and outside the military establishment. For any organization to thrive, especially the military, leadership must create a strong doctrine and sense of purpose for its agents. Nevertheless, strict bureaucracies such as the military are prone to policy errors, as the institutional leaders and people within these organization have difficulty thinking outside of their organization-biased scope. To ameliorate this situation, Petraeus drew on those inside the military who were, dissidents, skeptics, and outsiders (134). Additionally, some of Petraeuss closest advisors on counterinsurgency strategy were foreigners untouched by the established doctrine of the US military. One of his closest advisors, Sadi Othman, a Jordanian translator, said the following about Petraeus: Petraeus is always searching for new insights especially from people with different perspectives (144). By building a new strategy for Iraq through the help of people outside of the military, the US was able to formulate a more realistic game plan for the war going forward. Second, Petraeus was able to do what Gen Casey had never been able to do -- formulate a clear-cut strategy for his troops to implement on the ground. He communicated that the war in Iraq was a counterinsurgency and did away with the grandiose goals of democracy and state building of the previous leaders. The new primary goal was protecting the security of the Iraqi

people, by, putting troops among the people andprotecting the population (201). The formulation of a clear military strategy helped combat structural secrecy and allowed for greater local knowledge to combat the problem of mirror imaging. Under Gen Casey there was no defined strategy of how to wage the war. As a Colonel describes in the narrative, The biggest difference is, we have doctrine now (201). This led to a more transparent and well run military. Without a strategy from its leaders, the military did not act in concert and military leaders on the ground would carry out their own strategy independently. Structural secrecy insured that each part of the military above and below did not communicate its goals, tactics, and problems to each other. Instead, during the surge, for the first time since the invasion, US forces were all pursuing the same goal in the same way. A new counterinsurgency strategy formulated by previous skeptics of the war allowed for a, unity of effort [which] radically increases the effectiveness of military operations (201). By placing the troops amongst the people, the US military was able to garner local knowledge and combat a mirror imaging problem that had been present since before the war. In the lead up to the war and throughout the first three years of implementation, the US fell victim to mirror imaging, which is the assumption that the Iraqis think and act in the same way that the US does. However, by placing US troops amongst the people and allowing them to become familiar with both our enemies and civilians we could better see things through an Iraqi perspective. One example of this took place in the Iraqi prisons. Gen Stone, the new leader of the detention system, ordered his soldiers to interact more with the prisoners and treat them as they would like be treated. He said the following: [We] create risk when we make the mistake of judging a detainees actions in the context of our own culture, rather than his own (196). Outside of the prisons soldiers knew more about Iraqi culture and therefore were better suited to succeed by acting Iraqi. Ricks writes, in some ways, the story of the Iraq War in 2007 was the Iraqification of the American effort (219). Even with a large decrease in Iraqi and US casualties in July 2007 and onward, there are warning signs of more problems ahead. The surge was built on a clear cut, realistic strategy of stabilizing Iraq and securing the population. However, similar to when US troops marched through Bagdad in 2003, the question becomes what comes next? It is possible that some of our short-term strategy and success may have come at the expense of long-term problems. One such problem was our short-term tactic of power sharing. During the surge we employed Shiite militants while propping up Sunnis in power, carefully balancing ethnic tensions. However, as analyst John McCreary described in 2008, power sharing is always a prelude to violence (317). Another problem is the lack of a political strategy after the surge. As Ricks describes, military victory does not necessarily translate into a political gain (283). A lesson learned here is that a policy maker must always be cognizant of what comes next and plan for a realistic strategy for a transition period. The surge may have worked as a purely militarily strategy, fulfilling its shortterm goals, but the question remains, what comes next?

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- LoperAmid 1Document5 pagesLoperAmid 1Hemma KusumaningrumNo ratings yet

- Doyennés Et Granges de L'abbaye de Cluny (A. Guerreau)Document45 pagesDoyennés Et Granges de L'abbaye de Cluny (A. Guerreau)theseus11No ratings yet

- Altium Designer Training For Schematic Capture and PCB EditingDocument248 pagesAltium Designer Training For Schematic Capture and PCB EditingAntonio Dx80% (5)

- Research Proposal Sample OutlineDocument17 pagesResearch Proposal Sample OutlineGuidance and Counseling OfficeNo ratings yet

- Low Voltage Alternator - 4 Pole: 25 To 60 kVA - 50 HZ / 31.5 To 75 kVA - 60 HZ Electrical and Mechanical DataDocument12 pagesLow Voltage Alternator - 4 Pole: 25 To 60 kVA - 50 HZ / 31.5 To 75 kVA - 60 HZ Electrical and Mechanical DataDjamel BeddarNo ratings yet

- Lac MapehDocument4 pagesLac MapehChristina Yssabelle100% (1)

- Ayaw at GustoDocument4 pagesAyaw at GustoJed VillaluzNo ratings yet

- User Manual For Scanbox Ergo & Banquet Line: Ambient (Neutral), Hot and Active Cooling. Scanbox Meal Delivery CartsDocument8 pagesUser Manual For Scanbox Ergo & Banquet Line: Ambient (Neutral), Hot and Active Cooling. Scanbox Meal Delivery CartsManunoghiNo ratings yet

- Grief and BereavementDocument4 pagesGrief and BereavementhaminpocketNo ratings yet

- Engine Interface ModuleDocument3 pagesEngine Interface ModuleLuciano Pereira0% (2)

- THE FIELD SURVEY PARTY ReportDocument3 pagesTHE FIELD SURVEY PARTY ReportMacario estarjerasNo ratings yet

- Competency #14 Ay 2022-2023 Social StudiesDocument22 pagesCompetency #14 Ay 2022-2023 Social StudiesCharis RebanalNo ratings yet

- Dania - 22 - 12363 - 1-Lecture 2 Coordinate System-Fall 2015Document34 pagesDania - 22 - 12363 - 1-Lecture 2 Coordinate System-Fall 2015erwin100% (1)

- TLE CapsLet G10Document5 pagesTLE CapsLet G10Larnie De Ocampo PanalNo ratings yet

- Power Factor Improvement SystemDocument25 pagesPower Factor Improvement SystemBijoy SahaNo ratings yet

- NewspaperDocument2 pagesNewspaperbro nabsNo ratings yet

- MBTI - 4 Temperaments: Guardians (SJ) Rationals (NT) Idealists (NF) Artisans (SP)Document20 pagesMBTI - 4 Temperaments: Guardians (SJ) Rationals (NT) Idealists (NF) Artisans (SP)Muhammad Fauzan MauliawanNo ratings yet

- Cultivation and Horticulture of SandalwoodDocument2 pagesCultivation and Horticulture of SandalwoodAnkitha goriNo ratings yet

- A Seventh-Day Adventist Philosophy of MusicDocument5 pagesA Seventh-Day Adventist Philosophy of MusicEddy IsworoNo ratings yet

- Grade 7 - R & C - Where Tigers Swim - JanDocument15 pagesGrade 7 - R & C - Where Tigers Swim - JanKritti Vivek100% (3)

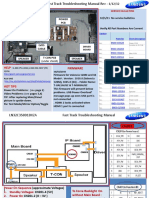

- Samsung LN55C610N1FXZA Fast Track Guide (SM)Document4 pagesSamsung LN55C610N1FXZA Fast Track Guide (SM)Carlos OdilonNo ratings yet

- A Child With Fever and Hemorrhagic RashDocument3 pagesA Child With Fever and Hemorrhagic RashCynthia GNo ratings yet

- Frogs and ToadsDocument6 pagesFrogs and ToadsFaris AlarshaniNo ratings yet

- Repeater Panel User GuideDocument24 pagesRepeater Panel User Guideamartins1974No ratings yet

- Pset 2Document13 pagesPset 2rishiko aquinoNo ratings yet

- Fluid Management in NicuDocument56 pagesFluid Management in NicuG Venkatesh100% (2)

- UntitledDocument45 pagesUntitledjemNo ratings yet

- Archaeology - October 2016 PDFDocument72 pagesArchaeology - October 2016 PDFOmer CetinkayaNo ratings yet

- CE 2812-Permeability Test PDFDocument3 pagesCE 2812-Permeability Test PDFShiham BadhurNo ratings yet

- A320 Abnormal Notes: Last UpdatedDocument13 pagesA320 Abnormal Notes: Last UpdatedDevdatt SondeNo ratings yet